32

32 32

32I leave this great people prosperous and happy.1

THE UPWARD TREND OF the American economy accelerated further, and again New York was in the lead, when governor DeWitt Clinton’s great public works project, the Erie Canal, opened on October 26, 1825. Consolidating the power of New York City as a trade center, it was an audacious engineering feat that connected the Hudson River with the far western reaches of the country and tied New York State together by means of a commercial waterway.

The Erie Canal project needed as many people as it could hire. It was an economic stimulus even while it was being built, lifting all boats, so to speak, before the locks were even in operation. Whatever skills or labor a worker could offer was useful in such a massive undertaking: calculating, carpentry, cooking, driving mules, ditch-digging. The people who lived in the area prospered by selling the laborers food, liquor, clothes, lodging, and services.

It was one of the young country’s proudest can-do moments. In the eight years it took to build, the canal employed some nine thousand wage laborers, many of them Irish, but also including free black laborers, including, from Saratoga, New York, the young Solomon Northup, later the author of Twelve Years a Slave. The Erie Canal was not built by slave labor. This was what a non-slave economy could do, and indeed by 1827 slavery ended in New York, following a period of gradual emancipation, providing the culmination of what some historians call “the first emancipation,” that of the North.*

The 360-mile Erie Canal supplied an unprecedented level of infrastructural improvement, connecting the vast land beyond the Great Lakes via the Lake Erie port of Buffalo to the state capital of Albany on the Hudson River, which ran 150 miles or so down to New York City.

By making it practical to get wheat from the western part of the state to New York’s harbor for export, the canal caused the value of New York State’s agricultural land to appreciate sharply, even as it created a path for distribution of finished goods from New York far into the interior—and it was a toll road, on which New York got paid coming and going. Because it was the only northern channel that crossed the Appalachians, it instantly became the major route to market for farmers and home manufactures across a large territory.

Fast-growing New York City had overtaken Havana in population sometime in the 1810s; now the Erie Canal, together with New York’s control of the Liverpool route and its Wall Street stock market, made the city definitively the number-one commercial center in the United States. It caused a massive appreciation of property values to the west as far as Chicago, which in the early 1830s was the subject of a tremendous real estate boom based on its position as a hub for water transportation. Goods from St. Louis and the “northwest” could now be brought to market via Chicago and New York instead of New Orleans. By 1836, the State of Illinois was digging a canal to connect Chicago directly to the Mississippi River, though it did not open until 1848.

Private capital had been insufficient to build the Erie Canal. It was a project of New York State, financed without levying taxes. The state bank sold bonds, and happily for the investors, they were easily paid back by the toll receipts the state collected. Every state wanted that kind of success. In Maryland, the ninety-one-year-old Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence and the wealthiest man in Maryland, whose family’s industrial arc had gone in two generations from colonial pig iron to republican railroads, turned over the first spade of earth on the Baltimore and Ohio, the nation’s first “common carrier” railroad, in 1828.

A mania for infrastructural improvement seized the nation, but the political class of the South was dead set against this kind of project. It would be a bad precedent for the labor regime of slavery if the federal government paid large numbers of free people to work. They were rentiers, living off their capital, and their capital was also their labor. If anything was to be built in their territory, they wanted it built by slaves rented from them, and they certainly didn’t want improvements elsewhere to be paid for by taxes or tariffs on them. Henry Clay’s “American System” of federally sponsored improvements, which counted among its successes the Second Bank of the United States and the National Road, was hated by Southern politicians and had been definitively stopped. With Andrew Jackson in the White House as of March 4, 1829, everyone knew that an extreme shift to limited federal government was about to begin.

Jacksonian rhetoric had freely levelled the charge of corruption against Adams, Clay, and the Bank of the United States. But Jackson’s party was utterly corrupt. His campaign had freely promised governmental positions in exchange for support, and once in office, his administration began purging public employees, especially postmasters, in order to replace them with political hacks in what became known as the “spoils system.”

Jackson continued the job of exiling Native Americans, conducted with the accustomed attitude of patronizing benevolence in the native negotiators were expected to, and some did, address him as “Father” and refer to themselves as “your children,” as he took their homeland away. The urgency of the process was accelerated by a minor discovery of gold in Georgia in 1829.

Along with a number of other Native American groups, the so-called Five Civilized Nations (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Cherokee, Seminole) still inhabited the region; Jackson in 1830 signed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized him to “negotiate” for them to leave. A series of treaties were signed, and the first deportations began in 1831. During the decade, perhaps as many as a hundred thousand Native Americans were “removed” westward in the Trail of Tears. Evicting them was a money-maker: politically connected businessmen could receive a $10,000 contract for “Indian removal,” which gave them an incentive to do it cheaply. The forced migration had perhaps a 15 percent mortality rate, which was about the same as the transatlantic slave ships—and indeed, much of the travel was by water, along river routes. More than three hundred Creeks died on the night of October 31, 1837, when the steamboat Monmouth, which was carrying them, collided with another vessel and sank.

The Seminoles, some of whom were black, would not leave and in 1835, a war began that lasted seven years. After capture, the Seminole chief Osceola, whose heritage was part Creek and part English and Scotch-Irish, was imprisoned in the old Spanish citadel at St. Augustine (by then called Fort Marion) and then moved to Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina.

No sooner had Native Americans withdrawn from a spot than a town sprang up; expansion onto the formerly occupied lands that Jackson had taken went as fast as the credit system would allow. Some 80 percent of the Chickasaw cession of the 1830s, sold cheap at the public land office, passed through the hands of speculators.2

The economic storm that raged during the eight years of Jackson’s presidency and for another decade or so afterward drew its energy from a variety of sources. At the eye of it was Jackson, who opened up credit as wide as it would go and threw away the controls. The economy had been subject to the characteristic cycles of capitalism all along, of course, but the bubble of the 1830s was spectacular. Fueled by a conjuncture of forces international and domestic, it took the slave trade to new heights.

The boom-and-bust of the 1830s took place in the context of a radical economic experiment in decentralization and deregulation in which President Jackson took a wrecking ball to the country’s financial structure, restructured it to operate without oversight, definitively abrogated a national role in the issuance of paper money, and shocked the system with abrupt rule changes. This is not to say that other crises would not have occurred had he not done that; but what did happen was the Panic of 1837, which led to the most severe depression in American history until the Panic of 1929.

It is ironic that the name of a man as autocratic as Andrew Jackson is associated with the word democracy.

“Jacksonian democracy,” that great trope of American history, grew out of, and expanded the reach of, that other great trope, “Jeffersonian democracy.” Jacksonians were loudly faithful to many of the ideals of the Jeffersonians. But whereas Jefferson imagined an agrarian rural republic of franchised property owners, Jacksonian democracy incorporated poor white men—the yeomanry of the Western frontier and the towns, the kind of person Jackson himself had been—into the franchise, thus promoting caste solidarity among white men of all classes at the expense of blacks. Indeed, it implicitly promised to poor whites that, being unenslaveable, they might someday become slaveowners, especially with so much land and credit available cheap. Enfranchising them invested them in white supremacy; Jacksonian democracy promoted white caste solidarity at the expense of black personhood.

Riches had never flown around so fast. Slavery could be incredibly profitable, especially when there was plenty of virgin Western land available and an unquenchable market for cotton that yielded cash returns as soon as slave labor could be applied to formerly native land. But even as a project for a racist democracy, or, as Sean Wilentz called it, “Master Race democracy,” Jacksonian democracy had little appeal to the patricians of South Carolina; uninterested in democracy of any sort, they formed a separate power bloc from Jackson, who in many ways represented political continuity with the old Virginia dynasty.3

It is also ironic that Jackson’s picture is on the twenty-dollar bill, because Jackson hated “ragg money” and wanted to get rid of it. Unfortunately, as his administration set out to, as the humorist Joseph Glover Baldwin satirically put it in a memoir of the era, “democratize capital,” Jackson’s actions made paper money less reliable than it had ever been, made government more economically inefficient, and drove the South to rely more on its human savings accounts.4

Jackson was a hard hard-money man. John Quincy Adams described Jackson’s final presidential message as containing an “abundance of verbiage about gold and silver and the injustice of bank paper to the laboring poor.”5 Jackson would have liked silver coins to have been physically exchanged for every transaction, like when he sold slaves for silver in Spanish Natchez. There wasn’t enough coin for the transactions of an expanding nation, but never mind, Jackson hated paper money, banks, and debt—a point of view that was understandable from a small-town merchant, but disastrous when applied to the nation’s economic system.

Jackson especially hated Henry Clay, whose party was for a time called the Anti-Jackson party; in a coalition with the Adams followers, they became the Whigs, with Clay as their losing presidential candidate in 1832. In what has been remembered as the Second Party System, these two main parties and a welter of smaller ones attempted to be national parties, connecting North and South. That was an attempt to straddle the fundamental dividing line of American politics, which was overwhelmingly slavery versus free soil. In both cases, making a national party required accommodating the slavery interest. Antislavery people in the North were growing in number, while Southern delegates grew steadily less interested in compromise.

Whigs, who came in slaveowning and antislavery varieties, were modernizers. Most merchants were Whigs, in favor of banks and corporations, federally sponsored internal improvements, protective tariffs, and national currency regulation—what we now call “big government.” Democrats, who saw all this as tyranny, were in favor of states’ rights, limited federal government, an agrarian republic, hard money, and were for the most part aggressively or reluctantly pro-slavery, though there were antislavery Jacksonian Democrats as well.

Modern Americans are accustomed to thinking of Mississippi as the poorest of fifty states, but in 1831, when it was growing explosively with new plantations amid a landgrab and a slave boom, it had, in Biddle’s words, “more rich proprietors than … any where else assembled.”6 Mississippi was the hottest lending location in the country, so in the spring of 1831, the Second Bank of the United States opened a branch—its last one, as it turned out—in Natchez. The Bank was not merely a presence in Natchez; it was aggressive, at one point concentrating 10 percent of its resources there.7

The Bank’s arrival transformed the state’s credit-hungry business environment. It was the legally mandated depository of federal funds, receiving federal income as it came in. By marketing federal debt to state and private banks, it controlled the money supply. It was far bigger than any state-chartered bank, and it kept something of a lid on the state banks by accepting their notes (“discounting,” it was called, reflecting the percentage adjustments that had to be made when using paper obligations), and immediately redeeming them for specie. It thus acted as a kind of regulator on how much paper the state banks could issue; its national reach allowed it to move liquidity around and help keep the entire system flowing smoothly. Biddle called it a “commercial railroad”; it was the main channel of exchange at the national level.8 The Bank was not unpopular, and it was powerful politically, being at the center of multiple webs of patronage—something Jacksonians wanted to monopolize. The paper money it issued could be exchanged for specie at any one of the Bank’s national branches, but in fact it was not necessary to do so, because its paper was known to be high-quality and was easily accepted by everyone, including slave traders.

As competition from the Bank’s new Mississippi branch forced the already existing State Bank of Mississippi (later called the Agricultural Bank) toward what would ultimately be liquidation, another bank appeared in the state: the Planters Bank. The Mississippi state legislature had chartered it in 1830, disregarding a state pledge made at the time of the first bank’s charter not to charter another bank. It was theoretically capitalized at $4 million dollars, half of it subscribed to by the state and paid for with 6 percent state bonds. Its charter promised to “by a creation of revenue relieve the citizens of the State from an oppressive burden of taxes, and enable them to realize the blessings of a correct system of internal improvement.”9

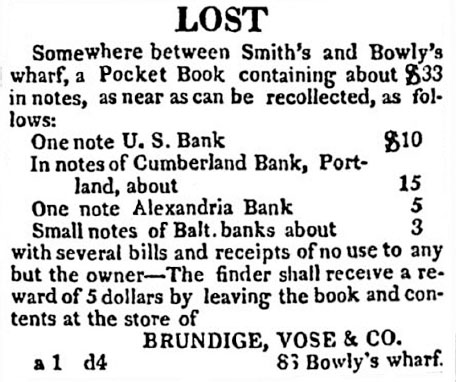

This lost-purse advertisement from the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser of April 1, 1819, gives a sense of what managing cash was like, listing money from different banks separately; the Second Bank of the United States’s note, the safest, most usable currency available, is listed up top as the largest denomination.

Except for the national bank’s notes, all paper money was local money, and negotiating it anywhere but its place of issuance was much like doing a foreign-exchange transaction today. As hundreds of banks appeared with licenses to print money, they all wanted to get as much of the money they printed into the public’s hands as possible, crowding the other banks’ paper out.

As the two state banks of Mississippi competed with the national bank to write mortgages, it was never easier to buy slaves on terms. The Natchez slave market soared; with Louisiana closed to out-of-state dealers in the wake of Nat Turner, the competition in Mississippi heated up. The banks’ bulging loan portfolios were capitalized largely by slaves, who trudged down into Mississippi in coffle after coffle.

Both sides in the presidential election of 1832 made the bank their major campaign issue. The Bank’s twenty-year charter was set to expire in 1836, but in the face of Jackson’s harassment of it, and at the urging of Clay and Daniel Webster, Biddle, the Bank’s president, proposed a recharter in 1832, gambling that Jackson would not dare kill it with the presidential election coming up, sneering at one point that “this worthy President thinks that because he has scalped Indians and imprisoned Judges, he may have his way with the Bank. He is mistaken …”10 (ellipsis in original)

It was a bad idea to call Andrew Jackson’s bluff.

We have previously noted Jackson’s capacity for hatred. When Jackson hated, it was not only he who hated. It was a popular movement of hate, sanctioned by God, and it was a political mechanism of hate. To hate the Whigs was to hate the Second Bank of the United States, which was aligned with them to the point of having financially supported Henry Clay, who for his part had the bad idea of making the Bank recharter an election issue. Moreover, Jackson’s first falling-out with the now-enemy Calhounites had been over the issue of the Bank, which they supported.

Destroying was what Jackson did best, and destroying the Second Bank of the United States was his obsession. Jackson saw the Bank as a federally sanctioned private monopoly, but whatever his ideological reasons for hating it, there was perhaps a more basic reason: it was the most powerful institution in the United States not under his control, and that alone was enough to seal its doom. The Bank’s recharter passed Congress, but was boldly vetoed by Jackson a week later, who issued an economically incoherent veto message authored by his bank-hating advisor and political fixer Amos Kendall that stoked sectional rivalries—not simply South against North, but positioning Jackson on the side of the good West versus the bad East, understood to be associated with the South and the North, respectively that “it is obvious that the debt of the people in that section to the bank is principally a debt to the Eastern and foreign stockholders; that the interest they pay upon it is carried into the Eastern States and into Europe, and that it is a burden upon their industry and a drain of their currency.”11

While Jackson was staring down the Bank, he also went up against the political chiefs of South Carolina. Four days after the veto, he signed the Tariff of 1832, or, as South Carolina politicians called it, the Tariff of Abominations. It was a laundry list of protectionisms with something for New England and something for the mid-Atlantic states; it had proved a vote-getter for Jackson nationally, who needed to shore up his political base in the North.

The slaveholding region saw it as a tax on them. Many in the South were not opposed merely to this specific tariff, but to tariffs in general, seeing them as tribute extorted by the North in a situation where the South produced the wealth but the North took the profits. In Mississippi, where nothing was manufactured and everything had to be imported, a writer to the Woodville Mississippi Democrat lamented that “there are ten spinning wheels and two looms in the county—such a thing as a slay, harness, shuttle or spindle is unknown, and if we want one of either we must send to yankee town for them.”12

For South Carolina’s politicians, Jackson’s signing of the tariff was a blunt dismissal of their political importance. They resisted with a level of virulence and extreme rhetoric that astonished other congressmen. Indeed, the vehemence of their “discontent” was not entirely rational, unless it was understood that the point of it was polarization: the tariff was a smokescreen issue with which ambitious politicians hoped to focus Southerners’ anger in order to drive a wedge against the North, with the ultimate end of fomenting disunion and provoking confrontation.

For two years or so, Calhoun had been promoting the doctrine of “nullification” that he had formalized, taking the name from Jefferson’s 1798 Kentucky Resolutions. In Calhoun’s vision, a state had the right to “nullify” a federal law within its borders, which also meant that the federal government had no right to impose tariffs. Never mind that federal revenue depended on tariffs, that was the idea: big slaveowners wanted a powerless federal government.

George McDuffie, from near the Georgia border, who had been “taken from labor in a blacksmith’s shop by Mr. Calhoun” to become a landed cotton planter and Calhoun’s loyal political lieutenant, was the grim-faced oratorical star of the 1832 South Carolina Nullification Convention.13 McDuffie, who was known to be irritable because of the painful wounds dueling had left him, had come up with something retroactively called the Forty Bale Theory, which held that a 40 percent tariff equaled taking away forty bales of cotton for every hundred a planter produced. That was utter nonsense, but it had the advantage of simplicity, and the Calhounites used the aggressive messaging technique that in more recent times has become known as “repeat until true.” Secession was threatened in congressional debates. Reprints of apocalyptically worded speeches, charged Representative John Reed of Massachusetts,

were dispersed, thick as autumnal leaves, through the whole region of the South, with other incendiary tracts, all calculated, if not intended, to rouse the whole South to madness … We were told in this hall that the protective system [of tariffs] was a vampyre, by which the North was sucking the warm blood of the South; that the free States were prairie wolves, gorging their jaws by instinct in the blood of the South, whilst oppression, robbery, and plunder were sounded to every note of the gamut. Is the result surprising?14

The argument over the tariff was in part a clash of factions in Jackson’s government. Van Buren, who was Jackson’s favored successor, had devised the tariff; Vice President John C. Calhoun made killing it his mission. As vice president under Adams, Calhoun had in 1827 cast the deciding Senate vote to kill a tariff, condemning it “as a sectional measure designed to impoverish the slave South,” in Manisha Sinha’s words.15 But it was hard for Calhoun to stay ahead of the pack of radicals at home who were pushing him to the right. William C. Davis describes their objectives as to “defeat protectionism and contain the growth of central power in Washington,” which was pretty much the same thing as maintaining the political power of slavery.16 As always, the dynamics in South Carolina were different: in much of the rest of the country, the voting franchise had been expanding, but not in South Carolina, where a two-party system barely took root, and where, as Sean Wilentz put it, “they had no use for the democratic dogma that appeared to be sweeping the rest of the nation.”17

Calhoun, Jackson’s backstabbing former ally, had become his open enemy—both socially (after Calhoun’s wife, Floride, ostracized Peggy Eaton, the wife of another cabinet member) and politically (after President Jackson belatedly learned that Calhoun had worked against him in the cabinet during his Florida conquest). Like Clay, Webster, and Benton, Calhoun had seen himself as a contender for the presidency. By now, it was clear that would never happen. But he could be president of an independent Southern nation, if one were to exist.

As a senator, Calhoun could more effectively promote nullification. He was appointed to the Senate by the South Carolina legislature—the state didn’t have the bother of a popular vote—on December 12. He resigned the almost powerless office of vice president on December 28, 1832, finalizing his break with Jackson. The South Carolina legislature, meanwhile, passed a bill that committed South Carolina to raising a military force to resist the tariff. Calhoun insisted that nullification did not necessarily mean secession, but then again, it might. As he started a short-lived Nullifier Party, the thrilling idea of secession—which would make the most belligerent politicians of South Carolina into the rulers of a sovereign state, as they insisted they already were—was in the air. Not all of South Carolina was in favor of nullification, but Unionists were derided and intimidated. Sinha writes that “the election campaign of 1832 was the bloodiest in the state’s history. Duels, which were usually personal affairs of honor, became the stuff of politics.”18 South Carolina went it alone; even in Mississippi the nullifiers lost.

Many years later, after Martin Van Buren had pivoted around to an anti-slavery stance, he wrote of the nullification standoff that “a more alarming crisis in the affairs of this country had never existed since the establishment of her independence.”19 But the nullifiers overplayed their hand when they went up against Jackson. He was pro-states’ rights, but as the last president to have personally suffered the violence of the War of Independence, he was a Union man until death. He denounced nullification in a ringing proclamation in December 1832, written by Secretary of State Edward Livingston. Capitalizing on his immense personal popularity and vowing to use fifty thousand troops if necessary to enforce the law, Jackson rallied the country to his side state by state, leaving South Carolina isolated.

It almost came to the point of an armed intra-Southern clash. According to Van Buren, Jackson was ready to get on a horse and personally direct an invasion of South Carolina, using Upper South troops to take out the Calhounites:

He had at this time … an inclination to go himself with a sufficient force, which he felt assured he could raise in Virginia and Tennessee, as ‘a posse comitatus’ of the Marshal and arrest Messrs. Calhoun, [Robert] Hayne, [James] Hamilton and [George] McDuffie in the midst of the force of 12,000 men which the Legislature of South Carolina had authorized to be raised and deliver them to the Judicial power of the United States to be dealt with according to law.20

South Carolina backed down. Jackson, who later expressed regret that he had not hung Calhoun when he had the chance, was re-elected president in 1832 by a landslide. In the wake of the nullification of nullification, a compromise tariff bill passed that would give South Carolina a climbdown from the failure of its insurrectionist posture by reducing tariff rates slowly. In the congressional debate over that bill, Representative Nathan Appleton, who as one of the founders of the New England textile industry and of the manufacturing center of Lowell, Massachusetts, was one of America’s heaviest domestic cotton customers and one of Boston’s richest men, asked point-blank:

Does the South really wish the continuance of the Union? I have no doubt of the attachment of the mass of the people of the South to the Union, as well as of every other section of the country; but it may well be doubted whether certain leading politicians have not formed bright visions of a Southern confederacy. This would seem to be the only rational ground for accounting for the movements in South Carolina. A Southern confederacy, of which South Carolina should be the central State, and Charleston the commercial emporium, may present some temptations for individual ambition.21

Two days before the beginning of his second term, on March 2, 1833, Jackson signed the compromise tariff that Southern legislators had voted for. But he also signed the revenue collection act that Northern legislators had voted for; known in South Carolina as the “Force Act,” it allowed him to use the military to collect tariffs and to close any port he desired.

Though the South Carolina legislature passed an act nullifying the Force Act in South Carolina, there was no armed insurrection against the federal government—this time. The experience left South Carolina more isolated, and its politics even more extreme than before.

“I have had a laborious task here, but nullification is dead;” wrote President Jackson in a letter on May 1, 1833, “and its actors and exciters will only be remembered by the people to be execrated for their wicked designs to sever and destroy the only good government on the globe.” The nullification struggle had been over the “Tariff of Abominations,” not slavery; but nullification was thoroughly identified with slavery and secession, and the crisis had been a rehearsal for leaving the Union, as Jackson saw clearly. The letter continued with his much-quoted observation that “the tariff was only the pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question.”22

For Jackson, as for Nathan Appleton and many other contemporary observers, the issue was the personal ambition of Calhoun and his argumentative countrymen.

Martin Van Buren’s autobiography describes Jackson

stretched on a sick-bed a spectre in physical appearance … Holding my hand in one of his own and passing the other thro’ his long white locks he said, with the clearest indications of a mind composed, and in a tone entirely devoid of passion or bluster—“The bank, Mr. Van Buren is trying to kill me but I will kill it!”23 [punctuation sic].

Stopping the Bank’s recharter wasn’t enough for Jackson. “The hydra of corruption is only scotched, not dead,” he wrote James K. Polk on December 16, 1832, after learning of Biddle’s plans to reintroduce a recharter.24 In response, Jackson drove a stake through the Bank’s heart to make sure the “Money Power,” as he called it in his 1837 farewell address, was dead. The Bank’s charter would be in force until 1836, but in September 1833, after two consecutive secretaries of the treasury had resigned rather than announce that the federal government would no longer deposit its funds in the Bank, Jackson’s new secretary of the treasury, Roger B. Taney, did it. At the time Jackson killed the Bank, it was operating twenty-five branches throughout the nation, though its operations in New England were much less significant because New England had a powerful banking system already in place. Jackson was the first president of whom we can speak as having “managers,” and there was a political payoff in destroying the Bank for one of them, New York’s Martin Van Buren. Wall Street was happy; the Bank had been the last remaining power base of Philadelphia in US finance. Jackson and Van Buren’s successful building of a national Democratic party was thus accomplished as a business alliance between slavery capitalism in the South and finance capitalism in the North.

In vetoing the Bank’s recharter, Jackson abrogated the federal government’s authority over paper money. He had hoped to do away with state banks next, but with the national bank gone, there was no alternative to state banks. But since the Constitution specifically denied to states the right to issue bills of credit, that left only private banks to print money. For the next thirty years, the United States had no uniform currency, as commercial institutions printed a massive uncontrolled emission of paper monies. This privatization of the money supply determined the commercial contours of the following decades, until the secession of the South provoked a new assertion of federal power by the Lincoln administration.

John Quincy Adams, whom Jackson defeated in the 1828 presidential election, was elected to Congress in 1830—the only ex-president to take such a step—and began a remarkable second career. His diary, which he began keeping at the age of twelve in 1779 and maintained for sixty-nine years until his death in 1849, is the most extensive by any American historical figure, and is a gripping record of the times and of a conscience. As it makes clear, he had always been antislavery; but as one of the major figures in increasing the territorial reach of the United States, he had been known as a pro-expansion president rather than an antislavery one. On his first day in Congress, however—December 12, 1831, only months after Nat Turner’s rebellion—he took advantage of his appointment as committee chair to present “fifteen petitions, signed numerously by citizens of Pennsylvania, praying for the abolition of slavery and the slave-trade in the District of Columbia,” and had one of them read out loud.25

It drove the Southerners in Congress mad. From then on, Adams delighted in presenting all the antislavery petitions he received. From the time he entered the House until he collapsed at his desk there in 1848 (remaining in the Capitol until he died three days later), no one in the US government opposed slavery more consistently or effectively.

Adams saw Jackson’s shuttering of the Bank as a baby-with-a-loaded-gun scenario, writing in dismay, “His experiment is to stake the revenue, the credit, and the currency of the country upon the State banks.”26 Petitions and even deputations came in from around the country: no, don’t do this. “They have all had interviews with the President,” wrote Adams, “who treated them all politely, but declared his irrevocable determination never to consent to the restoration of the deposits, and never to assent to the chartering of a Bank of the United States.”27 Slave trader Jourdan M. Saunders approved of Jackson’s action, writing his business partner David Burford on September 28, 1833: “We are looking out for hard times in the money market on account of the anticipated removal of the government diposits[.] The small [unclear: fry] are quaking[.] For my part I Glory in the Old Cocks [Jackson’s] inflexible determination to rid the country of a growing evil[.]”28

The Bank’s charter was to extend until 1836, but Jackson didn’t wait until then to stop the flow of federal deposits to it. The federal government began depositing its tariff revenues into twenty-three non-networked state banks, a number later expanded to sixty, and then to ninety-three, and then to fewer, and to fewer, as so many of them failed. Referred to by Jackson’s numerous enemies as “pet” banks, they were tools of the Jacksonian Democratic Party’s immense patronage machine, with which Jackson put the financial power of the federal government at the service of his political party.

Biddle had maintained a conservative 2:1 paper-to-specie ratio in the bank, but these new banks—“wildcat banks,” they were called—issued four, five, ten times as much paper money as they had specie to back it with. Sometimes they didn’t have specie at all, just other banks’ paper.

Biddle responded to Jackson’s choke order by pursuing policies consistent with liquidation, contracting credit sharply at all the bank’s branches, calling in loans and redeeming notes from state banks around the country, leading, predictably enough, to a panic in early 1834. Many criticized Biddle as trying to make the economy scream in a contest of wills, but his actions were consistent with Jackson’s order.

In Mississippi, the Bank of the United States strained the Planters Bank’s resources locally by taking away a major local source of credit and calling in its notes at the same time. The Planters Bank became one of the new depositories for federal funds, but unfortunately, when it finally received the first federal deposits, which came later than expected, “only a small percentage of the funds was in United States Bank notes or specie; a vast amount was in the paper of banks in Tennessee and Alabama, while the largest portion consisted of notes issued by the Planters Bank itself.”29 The government receipts that were being deposited were mostly revenues from the sale of public lands, which were being paid for in increasingly worthless paper.

Along with this, as a government depository, the Planters Bank also had the responsibility of paying out governmental obligations. If a government employee got paid with paper in Natchez, he no longer received paper money from the national bank, redeemable for silver coins at any bank branch in the United States. Instead, he got Planters Bank money, which, if he tried to use it in, say, New Orleans, would only be accepted at a discount from its face value.

Money, which had been moving in the direction of becoming a national commodity, became newly provincialized. Now that there was no national bank, and with lots of “virgin” land on the market whose new owners were in the market for slaves, the newly flush pet banks began competing aggressively to write mortgages. Meanwhile, state legislatures began granting bank charters freely as new operators got into the business. Against a backdrop of general inflation that was acutely felt by the increasing numbers of urban poor in the North, demand in Mississippi for slaves spiked, while supply remained constant.

Several bumper crops of cotton in a row had been sold into a growing industrial market in Britain. The British textile industry was continuing to expand, and there had been bumper crops of wheat in Britain, so British domestic consumers (who provided about half the market for British textiles), were relatively flush.30 Industrial capacity was growing: power looms in Britain grew from 14,500 in 1820 to about 100,000 in 1833, even as they were growing in size and becoming more efficient.31 This full-bore Industrial Revolution, which was creating wealth on a previously unknown scale, had enormous capacity to consume cotton. The French also bought American cotton, as did Lowell, Massachusetts, though its textile industry was tiny compared to the British juggernaut. Writing in humorist’s hyperbole, Joseph G. Baldwin later recalled Mississippi during these “flush times”:

Emigrants came flocking in from all quarters of the Union, especially from the slaveholding States … Money, or what passed for money, was the only cheap thing to be had…. The State banks were issuing their bills by the sheet, like a patent steam printing-press its issues; and no other showing was asked of the applicant for the loan than an authentication of his great distress for money … Under this stimulating process prices rose like smoke.32

In these times, there was a double incentive to buy large numbers of slaves: 1) those in possession of cotton-growing lands could make big money fast, if only they could get enough labor; and 2) the most obvious way to capture and store the value of the easy money flying by was to lock it down in the form of slaves before it devalued.

In Britain, a frantic dance of the millions took place in the great ballrooms of the economy: London, with its huge financial centers; Liverpool, the shipping emporium; and Lancashire, the industrial capital—all dancing as fast as they could, taking in cotton and turning out cloth for the world. As Peter Temin has pointed out, there was a surfeit of silver on the British market, partly because the Chinese were accepting opium instead of silver in trade from Britain.33 In another global trade first, Britain had addicted large numbers of Chinese to the product, flooding the market with opium cheaply grown in British-controlled India, sometimes shipped in Baltimore clippers built specially for the opium trade, in shipments sometimes financed by New England merchants, and licensed by the East India Company.34 Eighteen thirty-four, wrote Karl Marx in an 1858 article in the New York Daily Tribune, “marks an epoch in the history of the opium trade”: Britain’s East India Company was prohibited from trading in China, and opium was thrown open to separate traders, who began smuggling it into China aggressively, increasing the volume of the trade dramatically and demanding silver in return, depleting the Celestial Empire of the metal as the opium-seller’s customers multiplied.35

The growth of New England manufactures, together with the strong exports of cotton, shifted the balance of trade between Britain and the United States somewhat. As silver became cheaper on the British market, more of the silver Britain paid for cotton and other staple crops remained in America instead of being sent back out. That east-to-west trade winds influenced the economic collapse does not, however, make Jackson’s ideologically driven recklessness fade to insignificance. The global interconnection went both ways: the revenue derived from American cotton provided conditions for the storm to intensify.

Between 1830 and 1836, the number of state-chartered banks went from 329 to 730; they issued circulating banknotes and long-term bonds. 36 State governments borrowed heavily to finance internal improvements, most of which were never built. “From 1834 to 1836 the money supply grew at an average annual rate of 30 percent,” writes Jane Knodell, “compared to 2.7 percent between 1831 and 1834.”37 Canal, railroad, and bank projects all moved forward, with the Deep South states investing especially heavily in banks. During that time American indebtedness to foreign creditors doubled, from $110 million to $220 million.38 The state governments were on the hook for much of it. Intended to finance internal improvements, the money flowed through the American economic system; when it got to the South, it stimulated the market in slaves.39

Nicholas Biddle rechartered his bank under Pennsylvania state law as the United States Bank of Pennsylvania. Though it was still a giant in terms of capitalization, it was no longer the federal government’s agent and no longer had the advantages of national branches. But once again, its most extensive operations outside of Pennsylvania were in Mississippi.40

Jackson, meanwhile, achieved the conservative dream of paying off the national debt in January 1835. Unfortunately, that left the Treasury empty. Treasury coffers relied on income from tariffs, and now that the Nullifiers had succeeded in getting the tariffs down though not removed, there was a sharp drop in federal income. But with the switch to what in theory was a debt-free federal government, it was time for some other source of revenue, and the only contender was land sales.

There were vast quantities of newly available, unplowed land to privatize. It couldn’t go on indefinitely, but the federal government could make lots of money right now by selling the Native Americans’ land cheap, as fast as the natives could be evicted. Having an inside track on this market was valuable; as always with the Jacksonians, patronage was crucial to political power.

The Jacksonians opened up the floodgates of massive land speculation and currency at about the same time. Between January 1835 and December 1836, some fifty thousand square miles were sold at a fixed price of $1.25 an acre. Much of it was snapped up by speculators who flipped it, creating a real estate bubble, while banks issued paper money feverishly.41 Banks that were politically allied with the administration to be under the control of Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury had the free use of millions of dollars of public money, on which they were utterly dependent, as few of them had much in the way of assets otherwise.

The Whigs, wrote a nineteenth-century financial historian, “perceived that the system was exciting wild speculation, and that by it money was drawn from the great commercial centres and stored in remote banks to be loaned to the profit of those who had proved their loyalty to the administration and its ‘revered chief.’”42 One writer estimated in March 1837 that banknotes in circulation had been increased by $80 million since the veto of the bank charter in 1832.43

Field hands, meanwhile, might sell for $1,000 or more, so it was clear where economic power resided: in owning slaves. That was where the profit was taken, as gains made in dubious paper were converted into the safer instrument of laboring bodies.

Slave mortgaging was essential to the functioning of the Southern credit system, but the practice has not been much discussed by historians, and we do not have a good overview of the numbers. No one at the time seems to have compiled statistics about how much mortgaging was being done, whether of land or of slaves. Looking at South Carolina, Bonnie Martin found that “year in and year out … private mortgage contracts were quietly filed across the South, but no published tallies exposed the number of mortgages made or the amount of capital raised.”44

The function of banks in the antebellum mortgage market was different than the way we think of it now. Most antebellum mortgages were funded not by bank capital but by private individuals in local networks. The credit networks of the time were informal, and often banks were not the lenders but merely the places of payment, where loans were facilitated by the issuing of paper. Martin writes that of the publicly recorded mortgages that she was able to analyze, “banks, churches, merchants, and building societies were only 19 percent of the lenders who accepted human collateral in South Carolina. Interpersonal lending accounted for 81 percent.”45 The financiers and banks made money, of course, and so did states and municipalities that collected taxes and fees and, through the court system, did buying and selling of their own.

It’s clear that enslaved collateral was a significant part of the mortgage action: in the more than eight thousand mortgages she analyzed from Virginia, South Carolina, and Louisiana, Martin found that “the 41 percent of them that included slaves as all or a portion [of] the collateral raised 63 percent of the capital.”46

The price of slaves fluctuated with the rise and fall of cotton, but over the long term, those fluctuations were superficial disturbances of steadily increasing prices.

The era between the War of 1812 and secession can be thought of as divided into two periods of bumpy boom followed by devastating busts. The first of these booms ended in the complicated series of events remembered as the Panic of 1837, the exact dynamics of which historians have argued about ever since.*

After what we now call a “dead cat bounce” in 1838, the economy in 1839 crashed a second time, harder, landing in a depression that bottomed out in 1842 and did not immediately recover. By then, more than two hundred banks had failed. But for the strongest, most disciplined traders, there was still business to be done. In a letter of November 16, 1839, that somehow wound up in print in an abolitionist tract of 1846, the small-scale slave trader G. W. Barnes, of Halifax, North Carolina, informed the big trader Theophilus Freeman of New Orleans of the names of and prices at which he had shipped six “girls” to him, then wrote: “I have a great many negroes offered to me, but I will not pay the prices they ask, for I know they will come down. I have no opposition in market. I will wait until I hear from you before I buy, and then I can judge what I must pay…. Write often, as the times are critical, and it depends on the prices you get to govern me in buying.”47

The stimulus that got the economy pumping again was provided by the annexation of Texas in 1845, which stimulated the slave trade. It accelerated further with the discovery of gold in California in 1848 and the increasing penetration of railroads, and rose along with cotton to new heights. It dipped briefly with a Panic of 1857 that was caused in part, thought Natchez planter Benjamin Wailes, by “River lands at most unwarrantable prices & negroes at $1,500,” though the South was actually the least affected by the downturn.48 Then the slave trade went higher than ever, reaching unheard-of levels by 1860. That boom ended with secession, though the trade continued and even accelerated during the first three years of the war. But by then there was no longer any reliable money with which to compare prices, because the Confederacy was not part of the US financial system.

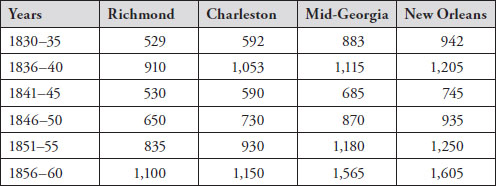

Not without a sense of irony, we will use white supremacist and onetime dominant-in-the-field-of-slavery historian Ulrich B. Phillips’s data showing prices in four major slave markets, not including Natchez, the highest-priced large market. While Phillips’s racist conclusions are thoroughly discredited, his numbers, in this case based on examining three-thousand-plus bills of sale, have been more or less generally accepted. As visually estimated by Robert Evans Jr. from Phillips’s graphs, the curve of five-year average slave prices (for “prime male field hands”) looks like this:

The effect of the post-1837 depression is clearly visible here, as is the economic tonic effect of annexing Texas in 1845. We see an impressive price rise over the fifteen years from 1845 to 1860, especially in Georgia. But a deeper wave was building that only broke with the ruin of war:

Slave prices inflated continuously as compared with the price of the cotton the slaves produced.

Here are Phillips’s figures for the Georgia cotton belt, which incidentally give a sense of how profitable slave trading was.49 With the importation of Africans no longer possible, the supply of African Americans onto the market could not keep pace with the amount of new cotton acreage continually being brought under cultivation, so the demand for labor always exceeded the supply. The degree of inflation slowed in hard times, but even then, the trend was upward.

| Year | Price of a prime field hand expressed in pounds of ginned cotton |

| 1800 | 1,500 |

| 1809 | 3,000 |

| 1818 | 3,500 |

| 1826 | 5,400 |

| 1837 | 10,000 |

| 1845 | 12,000 |

| 1860 | 15,000–18,000 |

At these intervals, we see no depression, only slowed growth. The price of a field hand in Georgia fell from $1,300 to $650 between 1837 and 1845, but measured against the price of cotton, over the course of those years, the field hand appreciated in value from ten thousand pounds of cotton to twelve thousand. Over the six decades of antebellum slavery, even as agricultural innovations gradually increased per-hand productivity, slave labor was steadily becoming a more valuable property than the staple crops the labor produced.

The mere fact of holding slaves, then, brought substantial capital gains. The pressure of this curve, as we need not remind readers, was felt in unsubtle ways by enslaved women, who were pressured to bear children. Newborn black babies were worth more on paper all the time, their poor life expectancy actuarialized through traders’ firsthand experience of discounting the substantial death rates. William Dusinberre believes that “about 46 per cent of slave children died before reaching the age of fifteen,” compared with a 28 percent mortality rate for free children.50 The higher mortality rate is no mystery, and it was needlessly high, as it turned on planters’ reluctance to spend on the health and welfare of the enslaved.

Even clean drinking water was sometimes seen as an unnecessary expense, which might explain the higher death rates of the enslaved from cholera. “Good water is far more essential than many suppose,” wrote a planter signing himself “A Citizen of Mississippi” in an article about plantation management titled “The Negroes” in DeBow’s Review of March 1847, “or than I could be persuaded myself until within a few years…. Cistern water not too cold will on any plantation save enough in doctor’s fees to refund the extra expense.”

But money spent on slaves’ welfare came right out of the plantation’s immediate profits. Some planters who could take the longer view—those who were not being ground down by debt—could see that any money that was spent on the health and welfare of the enslaved was of direct economic benefit to the slaveowner, and could also be cited as proof of the slaveowner’s purported kindness to his captives. “The great object,” continued the Mississippi planter, “is to prevent disease and prolong the useful laboring period of the negro’s life. Thus does interest point out the humane course.”51

The word humane was frequent in slaveowner vocabulary. On some large estates, children were taken off the various different parcels of land, away from their parents, and raised together in a collective nursery that made easily visible the slave-breeding nature of the Southern slavery project. A planter in North Carolina told the British geologist Charles Lyell in 1842 that, given the frequent necessity of breaking up families by sale, that “he defended the custom of bringing up the children of the same estate in common, as it was far more humane not to cherish domestic ties among slaves.”52 That is, since domestic ties were only going to be broken anyway, it was better not to create them in the first place. Labor that was capital had no family.

Despite its shorter average life span, the enslaved black population of the South grew faster than the white population, and faster than the small population of free people of color. The capitalized wombs of the South supplied boys, who were sold to traders, who sold them to planters so they could produce the cotton that would feed the steam-driven mills of Britain, France, and even New England. And they supplied girls, who could pick as much cotton as the boys, and who would themselves become captive baby makers. The slave-breeding industry was going full tilt.

*Until 1840, out-of-state visitors could bring slaves to New York with them for a period of nine months.

*The title of Jessica Lepler’s book The Many Panics of 1837 conveys something of the fragmented, unsynchronized quality of the multisited crisis.