39

39 39

39The little Boy has one of his toes cut off. I don’t think that will lessen his value … Doct Ingram has Known the Boy for a length of time and Says he never Gives him medicine but once for Belly Ache[.] he is Smaller than I like but it is hard to Buy at any price up here.1

IN HIS WILL, ISAAC Franklin directed that the income from his plantations support a school to be named the Isaac Franklin Institute, but his widow Adelicia got the court to void the provision, on the grounds that it would create a “perpetuity,” which in this case would have rested on the perpetual reproduction of the estate’s enslaved. Instead, she got the assets, including Fairvue.

The trustees’ management of Franklin’s estate terminated with the resolution of the widow’s court proceeding. During the five years or so of their management, seemingly every receipt submitted for every expense was collected and printed as part of the 918-page legal document titled Succession of Isaac Franklin, which thus provides an unusually detailed snapshot of the mercantile realities of the time. The trustees bought laudanum, morphine, calomel (mercury chloride, a toxic compound then believed to have medicinal value and often used as a laxative), and a host of other preparations for when the “negroes” were sick. They bought “negro shoes” from the Tennessee State Prison, which used convict labor to make salable products. They sold cotton and lumber.

Adelicia was presented to Queen Victoria when she visited London and was complimented on her riding skills by the horsewoman Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg. It was Adelicia who brought Spanish palominos to breed in Tennessee.2 With her new husband, Joseph Acklen, she became a leading light of the Nashville social scene at her new thirty-six-room mansion on her estate called Belmont, which besides ten thousand square feet of living space had a bear house and a zoo, and where her daughter Emma died of diphtheria.

John Armfield too became a respectable planter, and was a principal benefactor at the founding of the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee. Franklin’s former Richmond partner Rice C. Ballard became a planter as well, though he continued to be involved in the slave trade. He married and moved to Louisville, though he seems to have spent a great deal of time in Natchez, to judge from the letters he received there from his wife begging him for money.

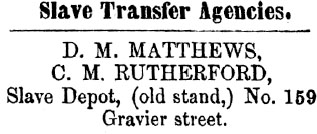

Ballard became friends, and then a business partner with, a Natchez judge named Samuel S. Boyd, with whom he co-owned a string of cotton plantations worked by perhaps five hundred slaves in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas. Boyd and Ballard’s man in New Orleans was a Louisville-based slave trader named C. M. Rutherford, whose office in New Orleans was at 159 Gravier Street, between Baronne and Carondelet, and who also sold slaves in Natchez.

It was advantageous for Ballard to keep a hand in slave retailing. He and Boyd at one point closed down a plantation and sold the entire labor force South, a few at a time. Ballard provided working cash for Rutherford to buy with, and Rutherford knew what Ballard liked, as when he offered him a woman “19 years old black likely and all rite as tall and likely as the one you wanted of white, price $700.”4

Boyd was cruel to women. The Natchez attorney J. M. Duffield had owned a woman named Maria, and though he was fond of her and had a sexual relationship with her, he wound up through financial pressures losing her to Boyd’s ownership. On May 29, 1848, Duffield wrote Ballard about Maria and her daughter (who may have been his daughter), asking him to intervene after she had been whipped “like an ox, until the blood gushes from her.” Another letter from Duffield reported on August 5 that “Mr. Boyd will part with her now as her health is such that she must be a charge on any owner,” as she suffered from “womb complaint dreadfully brought on by unkindness and injuries, bodily injuries, and … [now that she can leave Boyd,] she can now recover though she will probably linger out to several years.” Unfortunately, Duffield didn’t have any cash right then. He offered another slave as security, promising to pay “any price you might think she ought to bring, and perhaps prolong her life, which will soon be shortened where she is [now].”5

Southern Business Directory, 1854.3

On February 27, 1853, Rutherford wrote Ballard from New Orleans about a troublesome slave named Virginia, which may have been the name her mother gave her or may have simply been where she was purchased. Virginia was being sent as far away as Rutherford could manage, along with her swelling belly and her two children, who, though he didn’t need to mention it, looked like Judge Boyd. While Rutherford was trying to decide whether to “send her to Texas … or send her to Mobile,” she kept trying to run away.

Meanwhile, it was good to know a judge. On April 2, 1853, Boyd came to Ballard with a dirty deal—the lucrative prospect of selling a whole plantation full of freed slaves back into slavery:

Have lately learned of an opportunity to buy a lot of negroes at a very reasonable rate, next January.

Old man Baldwin, of Jefferson County, directed his slaves to be sent to Liberia. This will be declared void at the present term of the High Court, and as nearly all the heirs reside in New Jersey, they do not want the slaves, & are willing they should be all sold together, to a good master, at a reasonable rate, according to the will, if it cannot be carried out. {Name indecipherable}, one of the Executors, has informed me he thinks they can be had at … $27000 for fifty two. He is to furnish me with a list soon, and will endeavour to obtain authority to close the trade.

The same day, Rutherford wrote Ballard that he’d decided to send Virginia to Texas, but it was going to cost: he had “a friend there I can send her to but the vessels will not take any negro unless under the charge of some white person.” So eager were the partners to get rid of Virginia that Rutherford hired an escort to deliver her personally to Texas. From New Orleans, Rutherford handled her case to the point of final sale, offering easy terms, as Rutherford reported on April 19:

I have this morning shiped Virginia & children to S.B. Ewing Houston Texas with special instructions to sell her not to return to this place or Miss[issippi.] I gave her character and did not limit the sale when sold to permit account sales & nett proceeds to [factors] Nalle Cox & Co of this place for your benefit[.] I will give Nalle Cox & Co a copy of my letter of instructions[.] I had to hire a young man to go with her to Galveston.6

A letter from Boyd three days later that refers to Virginia only as “the woman” makes clear that she didn’t go quietly: “Rutherford was to ship the woman & her children to Texas on Tuesday last, by the steamer Mexico. She gave him a load of trouble.”

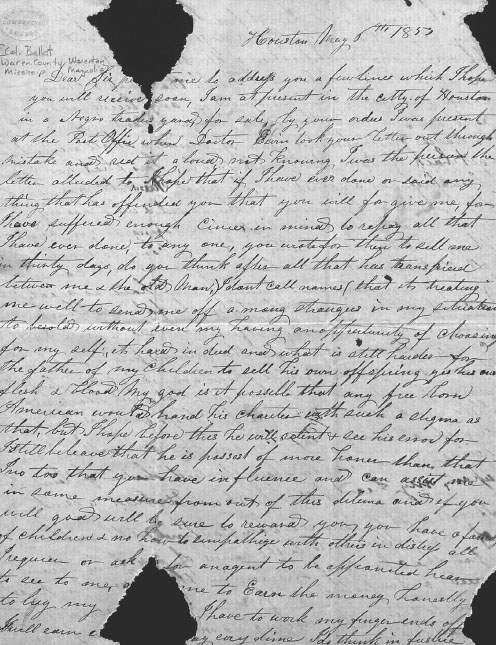

There exists a letter from the heavily pregnant Virginia to Ballard, written in the desperation of the moment.7 The dimensions of her story are apparent, even though much is unknowable about the events referred to. A facsimile is available online;8 we will present it here as we have transcribed it, adding full-stop periods, capital letters, and paragraphing for readability, with question marks indicating transcription queries, brackets around reasonable guesses, and Xs signifying missing bits of text.

Houston May 6th 1853

Dear Sir permit me to address you a few lines which I hope you will receive soon. I am at present in the city of Houston in a Negro traders yard for sale by your orders. I was present at the Post Office when Doctor Ewing took your letter out through mistake and red it a loud, not knowing I was the person the letter alluded to.

I hope that if I have ever done or said any thing that has offended you that you will for give me for I have suffered enough cince in mind to repay all that I have ever done to anyone[.]

You wrote for them to sell me in thirty days. Do you think after all that has transpired between me & the old Man )I don’t call names( that its treating me well to send me off a mong strangers in my situation to besold without even my having an opportunity of choosing for my self. Its hard in deed and what is still harder—for the father of my children to sell his own offspring yes his own flesh & blood. My god is it possible that any free born American would brand his charites with such a stigma as that, but I hope before this he will relent & see his error for I still beleave that he is possesst of more honer than that.

I no too that you have influence and can assist me in some measure from out of this dilema and if you will god will be sure to reward you, you have a family of children & no how to simpathize with others in distress.

all I require or ask [is] for an agent to be appointed hear to see to me, XXXXX to Earn the money, honestly, to buy my XXXXX I have to work my finger ends off I will earn XXXXXay evry dime I do think in justice [the] children should be set free XXXX[As] for my self altho my youthfull days [were worn] out in [t]he service and grattification of the [person that] now wants me & his children sold is it posible that such a change could ever come over the spirit of any living man as to sell his child that is his image[?] I don’t wish to return to harras or molest his peace of mind & shall never try get back if I am steall with family.

The first page of Virginia Boyd’s letter.

I no that you have been prejudist a gainst me, by what {name unclear} told you one day you will find who is the rascal & who has injured you most I have no motive in saying to you any thing but the pure truth, when you come to know all that she has said relative to you & matters concerning your family you will prehaps not have so great a confidence in all the tales she fabricates[.] I wish you to reflect over the subject and see if some little could be shown me for that mercy & pity you show to me god certainly will show you[.]

What can I say more if I ever have spoken hastly that which I should not I hope you will for give me for I hope god has, I am humbled enough all reddy, hear a mong strangers without one living being to whom I have the least shadow of claim upon, my heart feels like it would burst a sunder[.] It will not be long ere I am confined, & the author of my suffering to be the means of my being thrown upon the charity to strangers in XXXX when I most need a simpathizing friend is XXXXX that XXX to receive for making so mXXXX for his sattisfaction.

Will y[ou le]t me hear from you & say what yo[ur feelings] are relative to the proposition I make[?] [I know you are an] honerable high minded man and in your XXXX moments you would wish justice to be done to all, & if I am a servent there is some thing due me better than my present situation.

I have writen to the Old Man in such a way that the letter cant faile to fall in his hans & none others. I use any precaution to prevent others from knowing or suspecting any thing. I have my letters writen & folded put into envelope & get it directed by those that dont know the contents of it for I shall not seek ever to let any thing be exposed, unless I am forced from bad treatement.

Virginia Boyd

Some of the elisions in Virginia Boyd’s letter are accidental, some strategic. We can imagine the story; indeed, we have to in order to parse what we read. But there’s much we don’t know. Who is the “Old Man,” the father of her children she’s referring to? Presumably Boyd. She’s signing Boyd’s name as hers, with the clear indication that her children are to carry that name too. But Ballard was the one giving the sale order—apparently because Virginia was owned by the partnership, and Ballard handled slave sales.

Unlike Maria, Virginia at least got away from Boyd without being maimed. All three of the traders in the loop knew her; she indicates a personal familiarity with Ballard, who was a frequent visitor to Natchez, and to her co-owner—and who, she believes, has been turned against her by lies told by another enslaved female. We can make up stories about what that was about, but we don’t know.

What else might we know about Virginia? According to Rutherford’s earlier letter, she already had two children. She felt that her “youthfull days” were behind her. She might have been twenty-five, ready to be discarded as too old. What did she look like? She’d been the mistress of a slave trader, so she was presumably light-skinned. She wasn’t a field hand; she had been accustomed to privileges, and perhaps had imagined the goal of freedom for herself and her children to be getting closer. She expected to be able to “choose for myself,” suggesting perhaps that even her enslaved status had been in question at some point, but she has now been “humbled.”

The level of literacy in her letter is at least as good as the traders’. There is no reason to assume that it was written by a scribe; its twists and turns seem the product of a coordinated mind, voice, and hand. Somehow, we don’t know how, she had the ability to get letters sent by private channels out of the trader’s yard—one to Boyd, apparently, and this one to Ballard. And, she warns, if “forced from bad treatment” she could write another one that would tell what somebody doesn’t want known.

The blackmail threat did her no good. She was sold into the hard conditions of the Texas frontier. There’s no known record of her further existence. Her plea to free her children was ignored; slave traders didn’t set children free, they sold them, and they were inured to—perhaps even enjoyed—desperate pleas. Virginia was sold together with her younger child, whose gender we don’t know, for a thousand dollars. If that child was Boyd’s daughter, by light-skinned Virginia, she would have been “mighty near white”—a fancy girl, the slave trader’s premium prize. In a typical slave-trader move, Virginia’s older child, a girl, was kept back.

A letter of August 8 from Rutherford to Ballard said: “I recd a letter this morning informing me of the sale of Virginia & her Child reserving the eldest Child for $1000[.] I wrote Mr. Ewing not to sell the oldest child untill he heard from me … I recollect you wanted to reserve her before she went away which can be done now if you wish let me hear from you on the subject.”

Five months after Virginia was disposed of, Rutherford wrote Ballard from Natchez:

Since writing I have seen Judge Boyd[.] he tells me that he thinks you will want 10 to 15 more females[.] I have on hand I think 12 more but they are the kind you would not buy[.] I know they are such as I would not buy for you although they are large … you cannot buy anything like a fair woman here for less than $1000 any that you would have[.] I know a lot of Georgia negroes at Memphis that I think you could buy the women for $900 … I told the judge if you wished me I would go up there and buy you ten or fifteen & and charge you nothing but my expenses … Judge is in favor of my going if you say so.9

It may be that Isaac Franklin’s fantasy of a company “whore house” was not such an exaggeration.

In 1856, the year the secessionist leader and former governor James Henry Hammond was elected senator from South Carolina, he wrote his twenty-two-year-old son Harry a remarkably candid letter regarding the disposition of two sex slaves in the latest version of his will.

Hammond was something of an outlier in sexual behavior, as his confessional diary reveals. He wrote some of the only antebellum letters that survive documenting a sexual relationship between two men (with Thomas Jefferson Withers), and confessed in his diary to molesting all four of his teenage nieces from the marriage of Wade Hampton II to his wife’s sister. Hammond had purchased Sally Johnson, a “mulatto” seamstress, when she was eighteen, along with her (presumably lighter-skinned) one-year-old daughter Louisa, who became his concubine when she was twelve. He had children by both women—which is to say that, besides those children’s complicated relationship to each other, they were his son’s half siblings, as he explained in the letter to his son:

In the last will I made I left to you, over and above my other children Sally Johnson the mother of Louisa and all the children of both. Sally says Henderson is my child. It is possible, but I do not believe it. Yet act on her’s rather than my opinion.

Louisa’s first child may be mine. I think not. Her second I believe is mine. Take care of her and her children who are both of your blood if not of mine and of Henderson. The services of the rest will I think compensate for an indulgence to these. I cannot free these people and send them North. It would be cruelty to them. Nor would I like that any but my own blood should own as Slaves my own blood or Louisa.

I leave them to your charge, believing that you will best appreciate and most independently carry out my wishes in regard to them. Do not let Louisa or any of my children or possible children be slaves of Strangers. Slavery in the family will be their happiest earthly condition.10 (paragraphing added)

Among the greatest misfortunes Hammond considered himself to have suffered was that his captives died so frequently—“I have lost 89 negroes and at least 50 mules and horses in 11 years,” he lamented in his diary. Perhaps, he wrote, he should move their quarters to a less unhealthy spot.11

The Maxcy-Rhett house, informally known as “secession house,” in Beaufort, South Carolina. By 1850, the political class of Beaufort was already determined to secede. June 2013.