40

40 40

40Give us SLAVERY or give us death!1

THE DISCOVERY OF GOLD in California was a turning point on the way to Southern secession.

President Polk announced the find to the nation in his year-end message of 1848. Some ninety thousand gold-seekers arrived in northern California in 1849, staking their claims and displacing and murdering Native Americans en masse: the native population of the region dwindled in short order from about 150,000 to about 30,000.

Lured by the boom, immigrants came from Latin America and Europe to California and to the United States in general, and this on top of the massive Irish potato-famine migration that began arriving in numbers in 1847. Asian trade developed, Hawaii’s economy thrived, and Chinese workers, principally Cantonese, came to both Hawaii and California. As gold fever spread, men (who were perhaps as much as 95 percent of the early migrants) left home and family to go West; Nantucket found itself “drained” of “one-quarter of its voting population” in nine months.2 A song from the period described the mania:

The people all went crazy then, they didn’t know what to do

They sold their farms for just enough to pay their passage through

They bid their friends a long farewell, said “Dear wife, don’t you cry,

I’ll send you home the yellow lumps a piano for to buy.”3

With the discovery of other mines in the West, billions of dollars’ worth of new money was extracted over the ensuing decades. It was an immediate game-changer, with global implications. So much gold was sucked to Britain, the United States’ creditor and the world’s economic powerhouse, that it was easily able to consolidate its already in-progress shift to the gold standard.

Europe was troubled by a wave of revolutions. Beginning with a revolt in Sicily in January 1848 and a much bigger one in France the following month, insurrection spread to most of the continent. But it was put down within a year, and economic problems faded as the new money supply worked its way into the continent.

A mint was established at San Francisco as the United States issued unprecedented amounts of its own gold coinage:

| Year | Amount of gold minted into coins4 |

| 1848 | $3,775,000 |

| 1850 | $31,981,000 |

| 1851 | $62,614,000 |

| 1852 | $56,846,000 |

The flood of coins brought down the price of gold and drove silver out of circulation. With a domestic supply of gold, the United States could at last ban foreign money—most especially, the “Spanish dollar”—from circulation in 1857. The total amount of paper money issued by banks, in circulation and on deposit, went from $231 million in 1848 to $392 million in 1854, and $445 million in 1857—and the paper was of higher quality for having so much more gold in the system.5 Bankers and businessmen had a newfound sense of confidence and optimism, which made them more eager to speculate. The British were investing.

California was an immigration magnet. But it was as hard to get to San Francisco from New York as from Chile, and Chilean gold-seekers were indeed arriving. The Eastern US wanted a transcontinental railroad, and the United States government wanted control of the Central American portage crossing—whether in Honduras, Nicaragua, or, the ultimate choice, Panamá, the latter of which was then part of Colombia but would be pried away to become a zone of US influence.

It was the richest injection of precious metal into the global economy since the Hapsburgs had capitalized the world with gold and silver from Mexico and Perú. As the dimensions of the gold find became clear in 1849, the statehood of California was suddenly an urgent matter, before some other country tried to move in or before the miners decided to declare themselves an independent republic.

Unlike Louisiana, which had been slave territory before Washington took it over, California had been free territory under Mexico, and even slaveowner President Zachary Taylor was against establishing slavery there. But there was a powerful economic interest in favor of it: slavery in California would, it was widely believed, make the value of existing slaveholdings appreciate sharply.

A few slaveowners moved with their slaves to southern California, hoping to establish it as slave territory and take over the government, as had happened in Texas. But moving a plantation’s worth of captive laborers even a few hundred miles was a big undertaking, let alone the near-impossibility of taking coffles the fourteen hundred parched miles from Houston to Los Angeles.

Southerners saw gold mining as something that should be done by slave labor, purchased from them. But up in the north, the forty-niner gold miners, who drafted their own legal codes requiring small, continuously worked claims, weren’t about to have slaves working on massive gold plantations. They didn’t want slave labor or free black people, either one; for them, California was white man’s country. When a group of Texans headed by Thomas Jefferson Green tried establishing claims on the Yuba River in the names of their sixteen slaves in July 1849, miners informed them that “no slave or negro should own claims or even work in the mines,” and physically expelled them all.*6

The large state of California, extending all the way down to San Diego, requested annexation with a free-soil constitution in 1849, putting checkmate as they did so on the westward expansion of slavery. One delegate at the California constitutional convention, Henry Tefft, matter-of-factly referred to the slaveowners as “capitalists” when he warned the assembly that the young white male miner population “would be unable, even if willing, to compete with the bands of negroes who would be set to work under the direction of the capitalists. It would become a monopoly of the worst character. The profits of the mines would go into the pockets of single individuals.”7 A clause that would have barred free blacks from entering the territory was voted down.

In South Carolina, Robert Barnwell Rhett, outraged that a group of gold-digging migrants could declare themselves to define California and thus exclude slavery, derided the California constitution as “squatter sovereignty,” squatter being the preferred aristocratic epithet for poor rural whites, who often lacked legal title to the land they lived on. The states were the owners of the territories, argued the Fire-Eaters, and the slave states must be allowed to bring their property to their property.

Henry Clay, together with Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, attempted to placate the Slave Power with a grand compromise in January 1850 that was packaged by Mississippi unionist Henry Foote into a single “Omnibus” bill, which was then disassembled and recast into a series of laws known as the Compromise of 1850. It proposed admitting California as a free state and giving territorial status to Utah (later divided into Utah and Nevada) and New Mexico (later divided into New Mexico and Arizona), while disregarding Texas’s claims to New Mexican territory.

In Clay’s final grand speech after decades of fame as an orator, he attacked Massachusetts senator John Davis’s charge that Texans were trying to establish the “breeding” of slaves in New Mexico, a territory that was useless for plantation agriculture but which Texas was intent on annexing as slave territory.8 Davis, perhaps intimidated, denied having used the term, but Clay wouldn’t let him off the hook. He rhapsodized about how kind slaveowners were to their slaves and how sale into the market only was a painful last resort. Then he demonized abolitionists. He thus discredited himself in the eyes of posterity as a pandering apologist for slavery, while failing to please the Fire-Eaters, who wanted much more than Clay was prepared to give. Clay was a Unionist, and for him the Union meant the compromises that only he was adroit enough to manage.

The Compromise of 1850 included prohibition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Since Alexandria had left the District and returned to Virginia precisely over this issue, the interstate trade was not seriously disrupted, and in any case, slavery was not abolished in the District. But the secessionist project that was already well under way considered compromise to be treason, and the Fire-Eaters screamed bloody murder anyway.

For the North, the most offensive compromise was a new Fugitive Slave Act. Aimed at shutting down the Underground Railroad that emboldened the enslaved to escape, and building on the constitutional requirement to hand over fugitive “persons held to service,” it required lawmen to capture and deliver anyone in any state accused of being a fugitive slave, with no right of denial on the part of the accused. It gave kidnappers a legal apparatus.

Outraged by the “aggression” of ending the slave trade in the District of Columbia, Southern members of both houses of Congress met in a caucus and produced The Address of the Southern Delegates of Congress to their Constituents. Mostly written by the aged, embittered John C. Calhoun, it warned of emancipation’s awful consequences, expanding out into rings of ever more apocalyptic fantasy clad in the robes of prophecy. We offer one of its key passages as a glimpse into the routinely voiced Southern fear that white people would be on the receiving end of the violence of slavery:

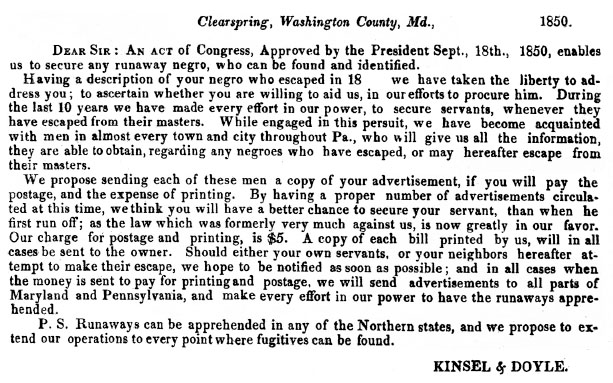

The Fugitive Slave Act stimulated Southern slave-catchers to expand their operations into the free-state North, as per this September 1850 mailing piece by Maryland firm Kinsel & Doyle, which boasts of its network in Pennsylvania. The legal occupation of fugitive-catcher easily served as a cover for illegal kidnapping operations targeting free people.

If [emancipation ] ever should be effected, it will be through the agency of the Federal Government, controlled by the dominant power of the Northern States of the Confederacy, against the resistance and struggle of the Southern. It can then only be effected by the prostration of the white race; and that would necessarily engender the bitterest feelings of hostility between them and the North.

But the reverse would be the case between the blacks of the South and the people of the North. Owing their emancipation to them, they would regard them as friends, guardians, and patrons, and centre, accordingly, all their sympathy in them. The people of the North would not fail to reciprocate and to favor them, instead of the whites. Under the influence of such feelings, and impelled by fanaticism and love of power, they would not stop at emancipation.

Another step would be taken—to raise them to a political and social equality with their former owners, by giving them the right of voting and holding public offices under the Federal Government. We see the first step toward it in the bill already alluded to—to vest the free blacks and slaves with the right to vote on the question of emancipation in this District. But when once raised to an equality, they would become the fast political associates of the North, acting and voting with them on all questions, and by this political union between them, holding the white race at the South in complete subjection.

The blacks, and the profligate whites that might unite with them, would become the principal recipients of federal offices and patronage, and would, in consequence, be raised above the whites of the South in the political and social scale. We would, in a word, change conditions with them—a degradation greater than has ever yet fallen to the lot of a free and enlightened people, and one from which we could not escape, should emancipation take place (which it certainly will if not prevented), but by fleeing the homes of ourselves and ancestors, and by abandoning our country to our former slaves, to become the permanent abode of disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness.9 (paragraphing added)

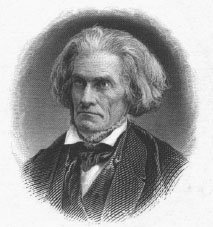

John C. Calhoun.

Frederick Douglass answered Calhoun’s negrophobic blast, referencing the Fugitive Slave Act:

We say to the slaveholder, Insist upon your right to make Northern men your bloodhounds, to hunt down your slaves, and return them to bondage. We say, let this be insisted upon, the more strenuously the better, as it will the sooner awaken the North to a sense of their responsibility for slavery, not only in the District of Columbia, and in forts, arsenals, and navy-yards, but in the States themselves; and will the sooner see their duty to labor for the removal of slavery from every part of this most unhallowed Union. In any case, nought but slaveholders have anything to fear.10

John C. Calhoun died of tuberculosis in March 1850, “with treason in his heart and on his lips,” in the words of his Senate adversary Thomas Hart Benton, who, like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, was by that time largely a spent force.11 When Calhoun began fomenting pro-slavery disunion, he was the only such figure on the national stage. His followers competed to be the most radical. In his final years, Calhoun had pushed aside Robert Barnwell Rhett, his longtime lieutenant, and had visibly passed his mantle to the man Rhett would come to hate most, Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis, who had war-hero status from the Mexican War.12

One of the first two senators from California was William Gwin, Andrew Jackson’s old crony from Isaac Franklin’s hometown of Gallatin, Tennessee. Gwin, who owned two hundred or so slaves, was an embodiment of the Slave Power. After becoming a congressman from Mississippi, he wrote Jackson on March 14, 1842: “I want a slaveholder for President next time regardless of the man believing as I solemnly do that in the next Presidential term the Abolitionists must be put down or blood will be spilt.”13 Relocated to San Francisco, he participated in California’s 1849 constitutional convention, where, presumably understanding that the free-soil measure would pass, he acceded to it graciously. Though he failed in his quest to bring slavery to the state, he was a happy man: he was the first slave baron to become a gold baron, having bought a mine that struck it rich. He organized the pro-slavery Democratic political faction in the California legislature—the so-called Chivalry wing, informally known as the Chivs.14

Gwin’s case was not typical. Slavery wasn’t in control of the gold mines, and as the world’s economy was transformed by the new money, the specie failed to go South. Ultimately, the California gold strike was the death knell for an archaic modality of agrarian capitalism. But the South had no way out; it was locked into holding its wealth in the form of slaves, with human fecundity still the road to monetary increase, while slavery was locked out of the Gold Rush.

Enormous tracts of land were coming on the market as East Texas cotton fields bloomed under the hands of trafficked-in slave laborers. Amid a generally inflationary environment, the price of slaves went up, up, up. But the largest movement of slaves South and West had already been completed; Texas and Arkansas were viable new markets, but Mississippi was already reaching its saturation point.

South Carolina’s overfarmed cotton land was playing out. Planters migrated westward, a little at a time, drawn by the lure of cheap land and a better deal. “By 1850 more than 50,000 South Carolina natives lived in Georgia,” writes Lacy K. Ford, “more than 45,000 lived in Alabama, and some 26,000 lived in Mississippi.”15 The cultural swath they cut as they brought laborers from the most Africanized population of North America remains a permanent part of American culture.*

South Carolinian politicians had been actively constructing an ideology for secession since the 1820s, if not all along, one that cast the Constitution as an instrument of oppression now that its original meaning had been perverted by abolitionists. By 1850, they were working to export the secession project to the rest of the South.

The more of a state’s land was under cultivation by slave labor, the more its politicians were apt to favor secession. Most of South Carolina was covered by plantations, with only a few counties in the north of the state not primarily slave-driven. In the plantation counties, nearly all the white population’s prosperity depended, one way or another, on the continuance—which meant, the exportation—of slavery. South Carolina, so heavily dependent on slave property, had the most concentrated core of support for secession, arguably followed in zeal by Mississippi.

In Maryland, only a minority were in favor of secession, though they were vocal. But slavery in Maryland was on the decline. Much of Maryland did not rely on slave labor; between manumission and sale of slaves down South, its enslaved population was actually decreasing. As Bancroft put it, “counting slave property as so much interest-producing capital, Maryland’s course, viewed superficially, was spendthrift, for it was steadily eating into the principal.”16

The enslaved of Maryland had the most chance to escape via the Underground Railroad; all they had to do was get across the border to Pennsylvania, then push on to Canada. From Baltimore, they might have a chance of slipping away on a boat, the way Frederick Douglass did. While the number of escapees via the Underground Railroad may have been statistically small, the existence of a path to freedom was psychologically significant. The South was a prison, but the enslaved knew there was an escape to the North.

With the West Coast becoming all free-soil, Southerners were desperate for an outlet to the Pacific. As the “Great Debate” over the new western territories continued, Congress mulled the possibility of admitting a state of Deseret (ultimately admitted as Utah), and there was talk of war as slave-soil Texas attempted to annex free-soil New Mexico.

The march of slavery had been halted at Texas. California was a free state. Now the South’s great obsession was its old dream of taking Cuba. A Cuban state in the Union would have two reliably pro-slavery senators. There was no way to make Cuba a free state; its slaves were creating too much wealth. Annexing Cuba would have dramatically boosted the values of extant North American slaveholdings—which is to say, the slave-breeding industry. The United States would not only annex Cuba, but also its enormous slave trade, which as part of the United States would no longer be supplied with Africans, but would have to buy slaves entirely from US sources. Virginia alone would not be able to supply such a demand.

Narciso López, a Venezuelan adventurer, briefly invaded Cuba in 1848, hoping to annex it to the United States as a slave state. With the backing of secessionist Mississippi governor John Quitman, who hoped to make Mississippi into a slave-breeding state for Cuba’s market, right across the Gulf, and with a cheering section that included John L. O’Sullivan, the New Orleans Delta, and the New York Sun, López invaded Cuba a second time. He organized his venture at the same jumping-off point as Austin’s Texas invasion: Banks’ Arcade in New Orleans. The one-star flag he flew, based on the Lone Star flag of Texas, first flew on Fulton and Nassau Streets in New York above the offices of the Sun; it was later adapted to become the flag of Cuba, and, with the colors reversed, Puerto Rico.

Landing at the northern Cuban port of Cárdenas with some six hundred men in May 1850, López found taking Cuba more difficult than he had imagined. Nor did he learn until he had safely escaped back to New Orleans that a number of Cuban slaves had stowed away in his boats, hoping to escape the plantation; they were returned to Cuba. López faced indictment for violation of the Neutrality Act, and Quitman was ultimately forced to resign his post as governor.

López invaded Cuba a third time, in 1851. He was captured and publicly garroted in Havana, using a screw-turn device that crushed his windpipe as he sat in a chair. In the wake of López’s failure, a secret society of Cuban exiles and Southern-rights supporters was formed in the United States to further the work of annexing Cuba and of the expansion of slave territory in general: the Order of the Lone Star, or OLS. Founded in Lafayette, Louisiana, with Pierre Soulé as its first president, the organization came to claim—almost certainly hyperbolically—some fifteen thousand members in ten states, with its greatest strength in the Alabama-Texas corridor.17

In response to the controversy over the Compromise of 1850, and growing out of a previous call by the late John C. Calhoun, Mississippi politicians announced a convention to be held at Nashville beginning June 1, 1850.

South Carolina was the only state to send a full delegation of four to the Southern Convention, also known as the Nashville Convention. Ostensibly held to discuss ways to preserve the Union, it was promoted by the South Carolinians to legitimize the idea of secession and, not incidentally, to position themselves as the leaders of the movement. Only nine of the fifteen slaveholding states sent delegates; most of those who attended were Tennessee locals.

We know what the room smelled like. The church where the convention was held had to replace its carpet afterward because of all the tobacco juice and cigar ash.18 We know that the delegates were entertained by a troupe of Swiss bell ringers. The Nashville True Whig and Weekly Commercial Register noted that, in St. George L. Sioussat’s paraphrase, “there was a noticeable identity in personnel between the southern advocates of the Nashville convention and the promoters of the expedition of General Lopez for the conquest of Cuba”—most notably Governor Quitman. “The refusal to admit Cuba as an independent Southern state into the Union,” said the newspaper, “is another ‘alternative,’ vaguely hinted at by Mr. Calhoun … to which ‘disunion’ would be preferred by the extreme Southern factionists.”19

Held in the city that was the heart of Jacksonism, the Nashville Convention drove another wedge into the crevasse between secessionists and Jacksonian unionists.20 In a letter to James Buchanan, the late President Polk’s close Tennessee ally Cave Johnson wrote: “Be not surprised if you should hear even me with my fifty or sixty negroes denounced for favoring the abolitionists because I will not yield to the mad projects of disunion that are now so freely talked of.”21

Rhett’s aggressive political strategy was much like South Carolina’s: take the most extreme position and fight from there. He was disappointed by the lack of secession fever from the other states, whose more moderate members, including unionist Sam Houston, carried the day. Only the South Carolina, Mississippi, and Georgia delegates—the states with the highest concentrations of slave labor—had been strongly in favor of secession. But more significant than the results was that delegates from Southern states had convened to talk about remaining in the Union—which was to say, to talk about secession.

Louisiana did not send delegates to the Nashville Convention, but the excitable French-born Louisiana senator Pierre Soulé proposed to the Senate on June 24 the extension of the Missouri Compromise line out to the West Coast, as the convention had recommended. Soulé wanted to divide California into two states, with the southern, slaveholding one to be called “South California.” Brandishing the by-now standard threat of disunion, he warned that not to leave South California open to slavery would be—he must have shouted it, because it was printed in all caps in the Congressional Globe—“TO EXCLUDE THE SOUTH FOREVER FROM ALL SHARE IN THE TERRITORIES, THROUGH SPOLIATIONS OF HER RIGHTS AND A DEGRADATION OF HER SOVEREIGNTY, WITHOUT AN ALTERNATIVE THAT DOES NOT END IN AN INGLORIOUS SUBMISSION, OR A RUPTURE OF THE UNION!”22

As the California debate dragged on, President Zachary Taylor became the second Whig war-hero president to die in office, succumbing suddenly from cholera on July 9, 1850, leaving behind an estate of 131 slaves to be divided among his three children by his lawyer, Judah P. Benjamin.23 As the nation lauded him, the Charleston Mercury was spiteful.

Taylor was succeeded by Vice President Millard Fillmore, who cleaned house and brought in his own cabinet. Fillmore, from Buffalo, New York, had been a moderately antislavery congressman who voted against the annexation of Texas. But President Fillmore refused to submit the New Mexico constitution to Congress, because it would have brought in another free-soil state and thus would have disturbed the balance in the Senate. “What is there in New Mexico that could by any possibility induce anybody to go there with slaves?” asked Daniel Webster in Congress. “Who expects to see a hundred black men cultivating tobacco, corn, cotton, rice, or anything else on lands in New Mexico, made fertile only by irrigation?”24

Texas’s motive for trying to take a big chunk of New Mexico may have been hostage-taking. The Republic of Texas had run up a heavy debt selling bonds that the State of Texas could not pay. Though Fillmore stood up to Texas’s attempted annexation of New Mexico, threatening to send troops, Texas got a bailout from its debts as ransom.25

Fillmore signed the compromise into law, and California became a state on September 9, 1850, which is why Fillmore’s name survived in San Francisco to become the name of a rock-concert palace in the 1960s; another of the city’s main thoroughfares is named Polk. But signing the compromise into law meant signing the Fugitive Slave Act, which cost Fillmore much support in the North and likely the election of 1852, which he lost.

Slavery had lost the contest for western expansion. But if the intense polemic from Calhoun and his successors had done nothing else, it had made leaving the Union thinkable in the South, and whatever the specific political issue being fought over, it was all about slavery. Increasing numbers of people in the slave states had severed the emotional attachment with a country that could harbor unprosecuted abolitionists. The nation’s churches had largely split into Northern and Southern over slavery. Slaveowners wanted Cuba badly, and the secessionists imagined that they were sure to have Mexico, Central America, all the way down.

When a second session of the Nashville Convention was called for November, the moderates stayed home. On November 14, 1850, the delegates heard the seventy-three-year-old veteran South Carolina politician Langdon Cheves deliver an oration that presented the case for immediate secession in fiery terms—if four states would do it. Since three were already in the bag, he was trying to convert just one of the attending delegations.

The South was not a particularly hospitable place for any Yankee, but for a Northern reporter deep cover was especially necessary. Joseph Holt Ingraham, a Maine-born Episcopal clergyman who discreetly published his letters under the name Kate Conyngham, saw Cheves as a “hale, white-headed old gentleman, with a fine port-wine tint to his florid cheek.”26 Cheves denounced abolitionists as communists, a term recently current from its use during the European-revolutionary year of 1848 in Marx’s Communist Manifesto and which would carry racialized connotations in Southern rhetoric into the Jim Crow era, when the Communist Party was the only one to call for full racial equality. Cheves conflated communism with democracy, as well as with jacobinism and anarchy. He denounced them all as equivalent to abolitionism, which he then dismissed with a minstrelic metaphor that referenced the old practice of blacking up one’s face before engaging in group attacks:

What we call the rights of man, or the admission of great masses to the power of self-government, has brought into action the minds of persons utterly unqualified to judge of the subject practically, who have generated the wildest theories…. This agitation has recently reached the United States. It has been introduced by European agents, and has brought under its delusions the subject of African slavery in the Southern States. It is of the family of communism, it is the doctrine of [the anarchist] Proudhon, that property is a crime. It is the same doctrine; they have only blacked its face to disguise it.27 (emphasis added)

Sliding into his big finish, Cheves called for southern unity by evoking a master-race utopia:

Unite, and your slave property shall be protected to the very border of Mason and Dixon’s line. Unite, and the freesoilers shall, at their peril, be your police to prevent the escape of your slaves; California shall be a slave State; the dismembered territory of Texas shall be restored, and you shall enjoy a full participation in all the territory which was conquered by your blood and treasure. Unite, and you shall form one of the most splendid empires on which the sun ever shone, of the most homogeneous population, all of the same blood and lineage.28

Cheves’s speech was no fluke: proslavery writers formulated the first generation of American anticommunist rhetoric. Southern ideology had coalesced into a vision of a worthy elite who governs while the unworthy multitude suffer, with South Carolina taking the philosophical lead.

Though the turnout at the Second Nashville Convention was disappointing, Rhett followed up by developing a plan with Quitman to call a secession congress in 1852. On May 7 of that year, Rhett abruptly resigned the Senate seat he had been recently returned to. Taking full control of the Charleston Mercury, the Fire-Eatingest newspaper in the entire South, he installed his son, Robert Barnwell Rhett Jr., as editor.

People were being convicted of abolitionism in South Carolina courts, though it was early yet in the building curve of hysteria that took nine more years to become cannonfire. It was not safe to voice even moderate antislavery views. The pro-secession British consul Robert Bunch wrote:

Persons are torn away from their residences and pursuits; sometimes ‘tarred and feathered’; ‘ridden upon rails,’ or cruelly whipped; letters are opened at the Post Offices; discussion upon slavery is entirely prohibited under penalty of expulsion, with or without violence, from the country.29

The Whig party barely outlived Henry Clay. It had divided into sectional wings, and by 1852 it was disintegrating. Former Whigs and antislavery Jacksonians met in the new Republican Party, which did not exist in the South.

The South Carolinian writer, editor, and statistician James Dunwoody Brownson De Bow began publishing his DeBow’s Review in New Orleans in 1846. A deluxe business-news publication, with articles on scientific agricultural management and new developments in technology, it was a voice of the modernizing wing of the pro-slavery movement. Perpetually in financial straits, because its subscribers tended not to pay up, the composition and printing of the magazine was done in the North, where the cost was a third what it would have been in the South, and the quality better.30 During the Pierce presidency, De Bow was placed in charge of the Seventh Census of 1850, the most detailed US census up to that time. As the 1850s passed, the Review’s pro-slavery, pro-secession positions became more extreme, as it looked toward a more industrial, technocratic, slave-driven South.

By the 1850s, in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act, the antislavery movement was making itself felt in the popular arts. Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852—a bestselling book that reached even more people in its numerous unauthorized stage adaptations.

William Wells Brown, previously the author of Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave (1847), became the first African American to publish a novel, though it could not be published in the United States at the time. Clotel, or the President’s Daughter (1853), was about fictional slave children descended from Thomas Jefferson, who was named in the book. Brown, at the time a fugitive from slavery—or, rather, from the Fugitive Slave Act—fled the United States for London, where the novel was published. He published other versions of it later, including an 1864 American edition that changed the fictional protagonist’s parentage from Jefferson to being “the granddaughter of an American Senator.”

Slave narratives became an established publishing genre. Solomon Northup, one of the few kidnapped free people to have descended into slavery and then been rescued, returned to his life in Saratoga, New York, and told his story in Twelve Years a Slave (1853), dedicated to Harriet Beecher Stowe. John Thompson, a literate slave who escaped Maryland via the Underground Railroad and became a whaler in New England and a stern Methodist preacher, self-published his autobiography in Massachusetts in 1856: The Life of John Thompson, a Fugitive Slave; Containing His History of 25 Years in Bondage, and His Providential Escape. Written by Himself. To out himself as a fugitive slave was a provocation in 1856, when lawmen anywhere in the United States were obligated to hand accused fugitives over without further proceedings. It was a public dare: here I am, come and get me.

Sentimental popular songs referred to the interstate slave trade: in response to Stowe’s book, Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home,” premiered in 1853 by Christie’s Minstrels, was at first titled “Poor Uncle Tom, Good Night,” before Foster rewrote it. It’s now the state song of Kentucky, but they don’t sing the third verse any more:

The head must bow and the back will have to bend,

Wherever the darkey may go:

A few more days, and the trouble all will end

In the field where the sugar canes grow.

A few more days for to tote the weary load,

No matter, ’twill never be light,

A few more days till we totter on the road,

Then my old Kentucky Home, good night!31

That’s a song about a black man from Kentucky being worked to death in a sugar prison camp in Louisiana. Benjamin Hanby’s tearjerking “My Darling Nelly Gray” (1856), which Hanby based on a story told him as a child by a black man named Joseph Selby, sang of an enslaved couple broken apart by a sale of the woman to Georgia:

O my poor Nelly Gray, they have taken you away,

And I’ll never see my darling anymore;

I’m sitting by the river and I’m weeping all the day,

For you’re gone from the old Kentucky shore.32

This genre of songs continued after the Civil War (James Bland’s “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny”), when they were bowdlerized and, bizarrely, repurposed into a nostalgia for the Old South.

Anthony Burns, a self-emancipated twenty-year-old man who had escaped from Virginia via the Underground Railroad, was apprehended in Boston on May 24, 1854, by a US commissioner acting on the behest of a slave-catcher hired by Burns’s former master. His case became a cause célèbre; one man was killed when a mob unsuccessfully tried to storm the courthouse to free him.33 But he was extradited to Richmond, where he was put into isolation at Lumpkin’s Slave Jail. The Boston journalist Charles Emery Stevens published a book about the case, which described the conditions under which Burns was held for four months:

The place of his confinement was a room only six or eight feet square, in the upper story of the jail, which was accessible only through a trap-door. He was allowed neither bed nor air; a rude bench fastened against the wall and a single, coarse blanket were the only means of repose. After entering his cell, the handcuffs were not removed, but, in addition, fetters were placed upon his feet. In this manacled condition he was kept during the greater part of his confinement.

The torture which he suffered, in consequence, was excruciating. The gripe of the irons impeded the circulation of his blood, made hot and rapid by the stifling atmosphere, and caused his feet to swell enormously. The flesh was worn from his wrists, and when the wounds had healed, there remained broad scars as perpetual witnesses against his owner. The fetters also prevented him from removing his clothing by day or night, and no one came to help him; the indecency resulting from such a condition is too revolting for description, or even thought. His room became more foul and noisome than the hovel of a brute; loathsome creeping things multiplied and rioted in the filth. His food consisted of a piece of coarse corn-bread and the parings of bacon or putrid meat. This fare, supplied to him once a day, he was compelled to devour without Plate, knife, or fork.

Immured, as he was, in a narrow, unventilated room, beneath the heated roof of the jail, a constant supply of fresh water would have been a heavenly boon; but the only means of quenching his thirst was the nauseating contents of a pail that was replenished only once or twice a week. Living under such an accumulation of atrocities, he at length fell seriously ill. This brought about some mitigation of his treatment; his fetters were removed for a time, and he was supplied with broth, which, compared with his previous food, was luxury itself….

One day his attention was attracted by a noise in the room beneath him. There was a sound as of a woman entreating and sobbing, and of a man addressing to her commands mingled with oaths. Looking down through a crevice in the floor, Burns beheld a slave woman stark naked in the presence of two men.

One of them was an overseer, and the other a person who had come to purchase a slave. The overseer had compelled the woman to disrobe in order that the purchaser might see for himself whether she was well formed and sound in body. Burns was horror-stricken; all his previous experience had not made him aware of such an outrage. This, however, was not an exceptional case; he found it was the ordinary custom in Lumpkin’s jail thus to expose the naked person of the slave, both male and female, to the inspection of the purchaser. A wider range of observation would have enabled him to see that it was the universal custom in the slave states….

After a while, he found a friend in the family of Lumpkin. The wife of this man was a “yellow woman” whom he had married as much from necessity as from choice, the white women of the South refusing to connect themselves with professed slave traders. This woman manifested her compassion for Burns by giving him a testament and a hymn-book. Upon most slaves these gifts would have been thrown away; fortunately for Burns, he had learned to read, and the books proved a very treasure. Besides the yellow wife, Lumpkin had a black concubine, and she also manifested a friendly spirit toward the prisoner.

The house of Lumpkin was separated from the jail only by the yard, and from one of the upper windows the girl contrived to hold conversations with Anthony, whose apartment was directly opposite. Her compassion, it is not unlikely, changed into a warmer feeling; she was discovered one day by her lord and master; what he overheard roused his jealousy, and he took effectual means to break off the intercourse.34 (paragraphing added)

Burns was sold at auction after four months to a planter, but his freedom was subsequently purchased by L. M. Grimes, a minister who had established a church for runaway slaves in Boston. Fugitive slaves had become pop culture by this point; according to Stevens, P. T. Barnum offered the newly freed Burns $500 to be an exhibit in his museum in New York, which Burns indignantly turned down, reportedly saying, “He wants to show me like a monkey!”35

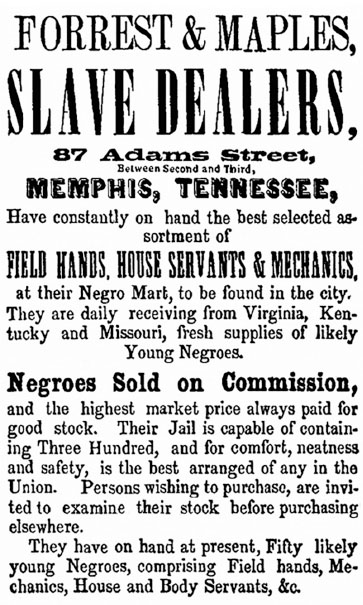

N.B. FORREST, Dealer in Slaves, No. 87 ADAMS STREET.

HAS just received, from South Carolina, twenty-five likely young Negroes, to which he desires to call the attention of purchasers. He will be in the regular receipt of Negroes from North and South Carolina every month.

His Negro Depot is one of the most complete and commodious establishments of the kind in the Southern country, and regulations, exact and systematic cleanliness, neatness and comfort being strictly observed and enforced, and his aim is to furnish to customers No. 1 servants and field hands, sound and perfect in body and mind.

Negroes taken on Commission. — Memphis Eagle and Enquirer, June 2, 1857.

The western Tennessee river port of Memphis was a jumpoff point for selling slaves into the new territories of Arkansas and Texas. Memphis was a mature slave market by 1852, when the thirty-year-old slave trader Nathan Bedford Forrest begins to appear in the city’s records. The hotheaded Forrest was at least as rash a man as Jackson, but had even less education. He instilled fear in those around him, and he didn’t stay business partners with anyone very long; for a year he worked in a partnership called Forrest & Jones; then, with the more established Byrd Hill, he cofounded Hill & Forrest; and by 1855 was partners with Josiah Maples in Forrest & Maples. He bought a double lot on Adams Street—named for John Adams, between Washington and Jefferson Streets—using 85 Adams for his house and 87 Adams for his jail, and soon he began to run the customary 500 NEGROES WANTED advertisements in the paper, while opening depots in other towns. He seems to have procured his merchandise in what had become the standard way: canvassing planters personally and via agents, buying people one at a time.36 It was no longer necessary to go to the Eastern Shore of Maryland to find farmers willing to sell slaves. These were the high-priced years of the slave trade, and profits came fast.

In a mythologizing account written at the time of Forrest’s funeral in 1877, Lafcadio Hearn, who was passing through Memphis at the time, wrote that Forrest was “reported to have been ‘kind’ to his slaves, yet to have ‘taught them to fear him exceedingly.’”37 White people were afraid of him, too. He did not hesitate to escalate to lethal action, as when he put a gun up to a tailor’s head for having delivered a bad suit.38 He made a lot of money in the slave business, some of which he invested in land, before winding it down in 1860 and getting out of it by 1861. Other traders continued in the business after the South seceded, but Forrest went to war, which allowed him to further develop the talent for blunt violence that had served him so well in slave trading.

A broadside advertisement for Nathan Bedford Forrest’s slave dealership in Memphis.

*The Oxford English Dictionary notes the emergence in 1856, in the United States, of a new word: vigilante.

*From its platform in Mississippi, the “Delta blues” reaches back across the southeast to South Carolina and Georgia. Georgia was the birthplace of the three singers who did the most to bring the vocal dynamics of the black church into the mainstream popular repertoire: Ray Charles, Little Richard, and James Brown.