44

44 44

44Both thy bondmen, and thy bondmaids, which thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen that are round about you; of them shall ye buy bondmen and bondmaids.

Moreover of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of their families that are with you, which they begat in your land: and they shall be your possession.

And ye shall take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them for a possession; they shall be your bondmen for ever: but over your brethren the children of Israel, ye shall not rule one over another with rigour.

PRESIDENT BUCHANAN CONDUCTED HIS administration in such a way as to leave his successor crippled.

Some of Buchanan’s few biographers have defended him against the charge of being part of a Southern conspiracy. But however one cares to address the topic, the notion that Buchanan could have been unaware of having methodically put the Union in the most disadvantageous position possible does not pass the smell test. His contemporaries certainly thought that was what he was doing.

Buchanan announced at the beginning of his term that he, like Polk, would be a one-term president, in effect setting the secession clock ticking. He sent the US Navy as far away as he could, where its personnel would not be easily available for duty in the event that, say, Carolinians or Mississippians should declare independence, as their leaders were constantly threatening to do. In 1858, he ordered “a fleet of nineteen ships”—seven of them chartered merchant vessels—“of two hundred guns manned by twenty-five hundred sailors and marines” on an unprecedented mission to Paraguay (!), where a US sailor had been killed in a river incident three years previously.1 Paraguay is a landlocked country, so the navy had to ascend three rivers. Most of the vessels stopped at Rosario, Argentina, and two continued on to the Paraguayan capital of Asunción, where they demanded an apology and extorted a new commercial treaty.

Following the completion of that expensive, time-consuming errand, Buchanan sent the navy to the African coast to police the slave trade—and indeed, for the first time, American enforcement did make a dent in it. The only captain ever hanged according to the legal penalty for engaging in the slave trade, one Nathaniel Gordon, was executed in 1862 under Lincoln, but he had been prosecuted and convicted during the Buchanan administration.

Riddled with procurement scandals, bribery, and “emergency loans,” and spending extravagantly on military adventures, Buchanan’s administration proved to be highly corrupt. Entering office with a $1.3 million surplus, Buchanan left behind a $25.2 million deficit, while government debt ballooned from $28.7 million to $76.4 million.2 Buchanan’s secretary of the treasury was Howell Cobb, his old Jacksonian friend and Georgia cotton planter, and at one time owner of a thousand slaves.3 Ostensibly a Unionist and the ex-Speaker of the House of Representatives, Cobb in 1856 had published A Scriptural Examination of the Institution of Slavery, a Bible-thumping defense of divinely ordained property rights in slaves that execrated various individual abolitionists, in which he complained—this is a mere sample—that:

Amongst the most successful schemes of mischief brought forth by abolitionists, may be reckoned what is familiarly called the Under-Ground Railroad: by this means, many owners have been deprived of their property by persons esteeming themselves, and being esteemed by their associates, pious.4

Asserting that enslaved women reproduced “like rabbits,” the slave-breeding Cobb in 1858 told the Georgia Cotton Planters Association (of which he was secretary) that “the proprietor’s largest source of prosperity is in the negroes he raises.”5 He was one of the key people informally known as the “Buchaneers” who helped make the Buchanan presidency a fiscal scandal of historic proportions. With him at the helm of Treasury, Buchanan ran his entire term on deficit financing, which Andrew Jackson would have regarded as a mortal sin if not treason. Such a thing might not seem so strange to modern readers, since the Federal Reserve can now print money to meet the government’s obligations, but this was an era in which there was no national paper currency. After three decades of a Jacksonian fiscal regime, the federal government was required to shift the physical location of pieces of gold and silver in order for federal spending to occur.

Besides the naval operations in Paraguay and Africa, Buchanan sent the US Army to Utah in 1857, to confront the theocratic Mormon state of Deseret. That was before there was a railroad to get the troops out there; they had to go on horseback, far from telegraph lines. Though hostilities ended in 1858, the army remained in Utah through the remainder of Buchanan’s presidency.

Buchanan’s vice president was Kentuckian John C. Breckinridge, the grandson of the man who had introduced Jefferson’s anonymous Kentucky Resolutions that first branded the doctrine of nullification. As the Democrats split into Northern and Southern factions, Vice President Breckinridge ran for president in 1860 on the Southern Democratic ticket, with a platform that was essentially a threat that if he lost, the South would secede. He did, and it did. When Lincoln won the election, it was with a plurality of votes on a four-way split; his name had not even been on the ballot in the Southern states.

In his final, lame-duck State of the Union Address on December 3, 1860, Buchanan explained the problem to the nation—the abolitionists made them do it: “The long-continued and intemperate interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the Southern States has at length produced its natural effects.”

By this point Northern bankers were refusing to buy Treasury notes for fear the money would go South; nor were they likely to invest in a situation in which the South was poised to repudiate its debts. Rhett’s Charleston Mercury wanted a new government, now. There was no time to lose: strike while the South has the momentum and the North is in transition.

Many in the North had thought the Southern hotspurs wouldn’t really secede. The plan to defeat the unprepared—and, the South thought, irresolute—North hinged on the idea of a quick mobilization. Howell Cobb had advised the secessionists to wait until the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, which would have saved their old friend Buchanan considerable embarrassment, but they ignored his advice, so Cobb resigned as secretary of the treasury on December 8 to get in on the ground floor of the new country.

It was clear what Cobb had done, wrote Henry Adams in the Boston Daily Advertiser of December 13: “Everyone knows that [Buchanan] has neglected to garrison Fort Moultrie; that Secretary Cobb has so managed the Treasury as to weaken the new administration as far as possible; and that Mr. Floyd [John Floyd of Virginia, secretary of war] has as good as placed large amounts of national arms in the hands of the South Carolinians.”6

As secession was declared in one state after another, Buchanan did nothing to stop it. Instead, he let them go to form a slaveholders’ confederacy that would attack and invade the United States—once he was gone, and a less compliant president inaugurated.

Before Lincoln took office in March, unidentified thieves removed all the remaining specie from the federal treasury in Washington.7 In William P. MacKinnon’s words, “By the time Abraham Lincoln took office in March 1861 the country’s largest military garrison was in the desert forty miles southwest of Salt Lake City, and the new administration could neither buy stationery nor meet the federal payroll. The two circumstances were not unrelated.”8 What little money the United States government had was in the form of pieces of metal scattered around the far-flung country. That was how the South wanted it. Moreover, the secession of seven states from the Union meant that many Northern creditors would be burned if not ruined, seizing up the nation’s commercial cash flow. Many of the merchants had been in favor of appeasing the South; but once they were stiffed by their Southern debtors, they became staunch Unionists.9

The secession campaign was planned and executed by a wealthy group of men who had been at war with the government years before they equipped an army against it. Their propaganda machine ran full blast: disunion was the only permissible stance. With the Charleston Mercury leading the charge, newspapers throughout the South hammered it home every day. When word of Lincoln’s election came, the Fire-Eaters were already mobilizing; Robert Barnwell Rhett and others founded the Minute Men for the Defence of Southern Rights, an action group, in October 1860, while the Knights of the Golden Circle were establishing paramilitary forces elsewhere.10

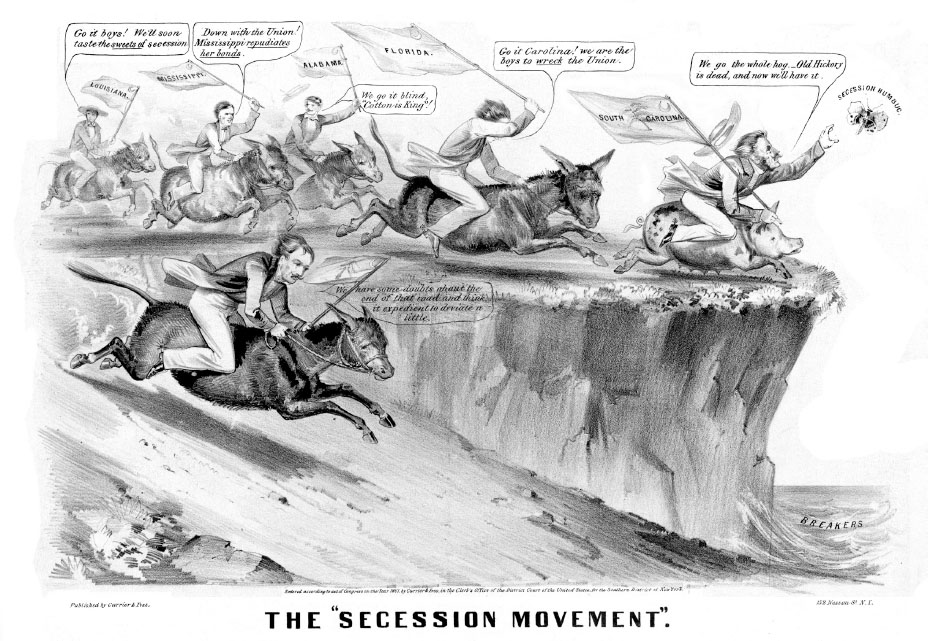

This Currier and Ives print in response to Florida’s secession on January 10, 1861, depicts South Carolina leading Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana off a cliff. South Carolina is shown as riding a pig in pursuit of a butterfly labeled “secession humbug,” and saying, “We go the whole hog … Old Hickory is dead, and now we’ll have it.” Georgia is depicted as deviating from the path, though in fact it seceded on January 19, before Louisiana did (January 26). The rider personifying Mississippi is saying, “Down with the Union! Mississippi repudiates her bonds!”—referring to the self-ruination of Mississippi’s credit on global markets almost twenty years before.

South Carolina had been the state most likely to secede since the beginnings of the nation—indeed, had barely joined the United States except for reasons of defense, which had been moribund since the removal of the Spanish, the British, and the local Native Americans following the War of 1812.

“All the slaves in Maryland might be bought out now at half-price with a liberal discount for cash,” wrote Henry Adams the week before South Carolina seceded.11 Not all the slave states were determined to secede, however, and in order to evangelize on behalf of disunion, the governors of Mississippi and Alabama sent “secession commissioners” to the various slave states.

Alabama’s commissioner to South Carolina, John Archer Elmore, arrived in time to address the first evening session of the South Carolina Secession Convention on December 17, 1860, warning them of what they already believed: that Lincoln’s election was “an avowed declaration of war upon the institutions, the rights, and the interests of the South.”12 The directorates that sent out secession commissioners tried to send natives of the states they were sent to, so Mississippi’s commissioner to North Carolina was North Carolina—born Jacob Thompson, President Buchanan’s secretary of the interior. It was straight-up treason: Thompson was still a cabinet officer when he arrived in Raleigh on December 18 to deliver a barnburner of a speech characterized by the “message of emancipation, humiliation, subjugation, and ruin” that ran “through the commissioners’ messages like a scarlet thread,” writes Charles B. Dew in his history of the secession commissions.13

The South Carolina convention voted unanimously on December 20 to secede from the Union. Anyone who might have dissented had long since been weeded out. When it was Robert Barnwell Rhett’s turn to ascend to the stage and take his turn signing the secession papers in the presence of three thousand cheering Carolinians, the most tireless and pugnacious disunionist of all “fell to his knees, lifted his hands upward toward the heavens, and bowed his head in prayer,” writes his biographer.14

South Carolina sent out well-coached secession commissioners, focusing them on the idea of a constitutional convention at Montgomery. Their commissioner to Alabama was John C. Calhoun’s son Andrew. Raised from birth at a high pitch of pro-slavery hysteria, the younger Calhoun had in November recalled that the Haitians had risen up “with all the fury of a beast, and scenes were then enacted over a comparatively few planters, that the white fiends [of the North] would delight to see re-enacted now with us.”15

As the appeals to secede became more intense, they became less economic and more emotional: if you don’t support the slaveowners, you will be the victim of the slaves. After winding himself up for several pages, Alabama secession commissioner Stephen F. Hale reached the boiling point of negrophobia that Haiti represented in this by now ritualized discourse, augmented as usual by the image of the violation of white women:

The election of Mr. Lincoln cannot be regarded otherwise than … an open declaration of war, for the triumph of this new theory of government destroys the property of the South, lays waste her fields, and inaugurates all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection, consigning her citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollution and violation to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans. Especially is this true in the cotton-growing States, where, in many localities, the slave outnumbers the white population ten to one.16

But the economic argument predominated. In a December 27, 1860, letter to Kentucky governor Beriah Magoffin, Hale put it down squarely to property rights in human beings: “African slavery has become not only one of the fixed domestic institutions of the Southern States, but forms an important element of their political power, and constitutes the most valuable species of their property, worth, according to recent estimates, not less than $4,000,000,000; forming, in fact, the basis on which rests the prosperity and wealth of most of these States.”17

Howell Cobb supervised the hasty, secretive drafting of the Confederate Constitution at Montgomery, Alabama, with a team that included his brother Thomas, Robert Toombs, Robert Barnwell Rhett, and Alexander Stephens. This constitution explicitly mentioned slavery—ten times. Cobb served as temporary head of the six-state Confederate States of America for two weeks, until Jefferson Davis was selected president of the self-declared new nation and was inaugurated on February 18, 1861.

Alexander Stephens of Georgia was declared vice president of the Confederacy. President-elect Lincoln had written Stephens on December 22 that, as the Republicans had insisted throughout the campaign, he had no intention of abolishing slavery where it existed, only of prohibiting its spread to other territories.

But of course, to stop slavery’s expansion would have been to end it.

So effective was the sermon Mutual Relation of Masters and Slaves as Taught in the Bible at the First Presbyterian Church of Augusta, Georgia, on January 6, 1861, that the congregation quickly raised the money to publish it.18

Its author, the twenty-five-year-old clergyman Joseph Ruggles Wilson, based his text on Ephesians 6:5-9; the passage begins, “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.” Affirming that the Greek word translated as “servants” “distinctly and unequivocally signified ‘slaves,’” Wilson saw slavery as a permanent Christian institution. Expounding the Southern churches’ doctrine, which had occasioned a break with their Northern denominations’ counterparts, he proposed that as servants of Christ, masters should treat their slaves with love and slaves should work hard. This was the doctrine known as “paternalism,” in which slaves and master were portrayed as forming a big family—until it was time to sell some of the family.

Only fifteen days before Georgia seceded, Wilson told his parishioners to prepare for the upcoming victorious struggle, speaking of slavery as something to “cherish”:

We should begin to meet the infidel fanaticism of our infatuated enemies upon the elevated ground of a divine warrant for the institution we are resolved to cherish….

[The Apostle Paul] as much as says, that it is unnecessary to fear that this long-cherished institution will first give way before the enemies who press upon it from without. If slaveholders preserve it as an element of social welfare, in the spirit of the christian religion, throwing into it the full measure of gospel-salt allotted to it, and casting around it the same guardianship with which they would protect their family peace, if threatened on some other ground—they need apprehend nothing but their own dereliction in duty to themselves and their dependent servants.

He closed by anticipating prosperity for slaveowners and holiness for the enslaved:

Oh, when that welcome day shall dawn, whose light will reveal a world covered with righteousness, not the least pleasing sight will be the institution of domestic slavery … which, by saving a lower race from the destruction of heathenism, has, under divine management, contributed to refine, exalt, and enrich its superior race!19 (emphasis added)

We do not know whether Wilson’s son, Woodrow, attended his father’s sermon that Sunday during secession winter, because he had just turned four. But his subsequent writings as a historian and his adult actions suggest that he absorbed the racist message of his father, with whom he had a lifelong loving relationship.*

Rather than “submit” to the “Black Republicans”—so went the rhetoric—Mississippi seceded on January 9, 1861, followed by Florida (which had only been a state for fifteen years) on January 10, Alabama on the eleventh, and Georgia on the nineteenth.

On January 21, five Southern Senators withdrew from Congress. In his brief valedictory speech, Jefferson Davis, owner of 113 slaves,20 said:

It has been a belief that we are to be deprived in the Union of the rights which our fathers bequeathed to us, which has brought Mississippi to her present decision. She has heard proclaimed the theory “that all men are created free and equal,” and this made the basis of an attack upon her social institutions; and the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races.21

Davis went on to explain, as slaveowners frequently did and as the US Supreme Court had affirmed, that “all men were created equal” had not been intended to mean all men. Jefferson’s youngest grandson, George Wythe Randolph, who as a boy stood by Jefferson’s deathbed, apparently agreed: he was the Confederate secretary of war for eight months in 1862.22

Neither Virginia nor Maryland had seceded when, with Louisiana’s P. G. T. Beauregard giving the orders, slavery “fired on the flag,” in Ulysses Grant’s words, on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter.23

Virginia did much business with the North and was decidedly ambivalent about seceding. The Confederate Constitution, signed as of March 11, offered Virginia both a carrot and a stick. The document was modeled on the US Constitution, complete with a three-fifths clause, but with explicit protections for slavery written into it. However, even despite the latter-day clamor to reopen the African slave trade, the Confederate Constitution prohibited the foreign slave trade into the Confederate States with what might as well have been called the Virginia clause.

The carrot, then, was that a Confederate Virginia could continue to slave breed and thus retain a market capitalization of its enslaved population. With importation prohibited and conquest continuing, Virginia slaveowners could sell black people into new domains for the foreseeable future. But the stick was that since no foreign slaves could be traded into the Confederate States, if Virginia did not secede she would have no Southern market in which to sell African American youth.

Virginia gave in and joined the Confederacy. Facing the loss of the state’s slave-breeding industry, a Virginia secession commission voted provisionally to secede on April 17—five days after South Carolina fired the first shot at Ft. Sumter, and after Lincoln had called for seventy-five thousand troops from all the states remaining in the Union. After Virginia ratified secession on May 23, West Virginia, where slave labor had never been much in use, seceded from Virginia, voting itself a Union state on October 24.

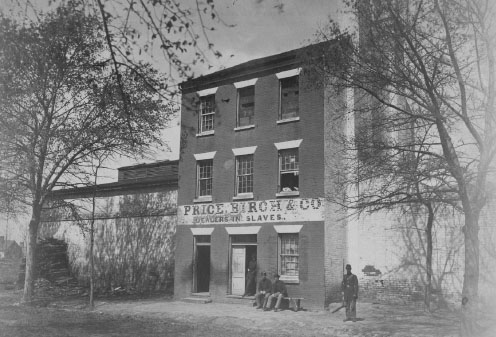

The day after Virginia seceded, Union troops moved into Alexandria, beginning the longest occupation of a long war. They surprised the Confederate cavalry eating breakfast at the Duke Street slave-shipping compound that had formerly been Franklin and Armfield’s, and at that time was on its fifth owner, Charles M. Price, who had been a partner with James Birch in Price, Birch. “The firm had fled,” wrote Virginian M. D. Conway, “and taken its saleable articles with it; but a single one remained—an old man, chained to the middle of the floor by the leg. He was released, and the ring and chain which bound him sent to the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher.”24 The “Slave Pen,” as it was known, was repurposed as a prison for captured Confederates.

A divided Maryland did not secede, but continued to have slavery and was heavily occupied by the military. It was a fundamental priority for the United States to keep Maryland, because if Maryland went, Washington would be surrounded.

Kentucky did not secede. John C. Breckinridge was seated as a senator from Kentucky, subsequently enlisted in the Confederate army, and was formally expelled from the Senate as a traitor on December 2, 1861. Missouri, the most bitterly divided state, did not secede, but a faction announced a provisional Confederate government in the town of Neosho.

The captured Price, Birch & Co., “Dealers in Slaves.” Photograph: Andrew J. Russell, sometime between 1861 and 1865.

The capital of the Confederacy was moved from Montgomery to Richmond by a May 20, 1861, vote of the Confederate Congress. In eighty-two years, Richmond had gone from being the capital of Virginia’s secession from Britain, to being the great wholesale center of the domestic slave trade, to being the Confederate capital. Prices for slaves remained strong, and slave sales continued until the city fell to the Union in 1865. Richmond versus Washington: the capitals of North and South were only a hundred miles apart.

Among the defects of Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln was the short shrift it gave Elizabeth Keckley.

Though depicted in the movie as a servant, she was the first African American couturier of note. Born enslaved in Virginia, and badly abused during slavery, after manumission Mrs. Keckley (as she was addressed) married and divorced, then opened her own dressmaker’s shop as a modiste in Washington, DC. At one point she had simultaneously as clients both Varina Davis (the wife of Jefferson Davis, at the time a Mississippi senator) and Mary Todd Lincoln.

She became the confidante of the unpopular Mrs. Lincoln and was frequently present in the White House. Her 1868 memoir, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, was written with the abolitionist journalist James Redpath, who probably transcribed and tweaked her speech to create an “as told to” text. It would make a fine movie, complete with a unique, close-up view of Lincoln and his short-lived son Tad watching their pet goats play on the White House grounds. In it, Mrs. Keckley reported a conversation with Varina Davis:

While dressing her one day, she said to me:

“Lizzie, you are so very handy that I should like to take you South with me.”

“When do you go South, Mrs. Davis?” I inquired.

“Oh, I cannot tell just now, but it will be soon. You know there is going to be war, Lizzie?”

“No!”

“But I tell you yes.”

“Who will go to war?” I asked.

“The North and South,” was her ready reply. “The Southern people will not submit to the humiliating demands of the Abolition party; they will fight first.”

“And which do you think will whip?”

“The South, of course. The South is impulsive, is in earnest, and Southern soldiers will fight to conquer. The North will yield, when it sees the South is in earnest, rather than engage in a long and bloody war.”

“But, Mrs. Davis, are you certain that there will be war?”

“Certain!—I know it. You had better go South with me; I will take good care of you…. Then, I may come back to Washington in a few months, and live in the White House. The Southern people talk of choosing Mr. Davis for their President. In fact, it may be considered settled that he will be their President. As soon as we go South and secede from the other States, we will raise an army and march on Washington, and then I shall live in the White House.”25

The Yankees wouldn’t fight. Varina Davis would live in the White House. New York would collapse without the money it stole from Southern cotton producers, and the poor would riot and burn down the mansions on Fifth Avenue. It was a common belief. Lazarus Straus’s son Oscar, who would have been nine or ten years old at the time, vividly recalled hearing Georgia senator Robert Toombs speaking at Columbus’s Masonic Temple: “He drew a large, white handkerchief from his pocket with a flourish, and pausing before mopping his perspiring forehead, he exclaimed: ‘The Yankees will not and can not fight! I will guarantee to wipe up with this handkerchief every drop of blood that is spilt!’”26

Toombs’s ghost must be mopping up the blood still. At the time he made that extravagant remark, he hoped to become the Confederate president, as did Howell Cobb. But Jefferson Davis had the most military credentials, and running a war was going to be pretty much the Confederate president’s only job. Davis’s older brother Joseph had for years been promoting him as the obvious chief executive of an inevitable Southern republic. In order to keep his talented sibling free of financial worries, Joseph had given him the plantation called Brierfield, twenty miles south of Vicksburg, whose captives were capably overseen during Jefferson Davis’s extended absences by an enslaved man, Davis’s longtime “body servant” James Pemberton.

Many in North and South alike believed that Lincoln would be no match as a warrior for Davis, who was unanimously named president of the Confederate States of America by the hastily convened Confederate Congress, which met in secret during its entire existence.

*When he was president of Princeton, Wilson kept out black students; as president of the United States, he implemented Jim Crow in the federal government, requiring job applications to include photos.