45

45 45

45Every intelligent man knows that coined money is not the currency of the country.1

After the Civil War was over, ole Marsa brought some money in a bag and says to his wife that it wasn’t no count. What was it they called it? Confederate money? You know when the War ceased money changed—greenbacks, yes’m.2

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT COST a million dollars a day, maybe more, to run.3 There was nothing to run it with.

Lincoln did not merely inherit a ransacked treasury and a government in debt from James Buchanan and Howell Cobb. He inherited more than thirty years of Jacksonian hobbles on the financial powers of federal government. In the years since Jackson had first become president, the United States had become an industrial and financial power fueled by earnings from the massive export of cotton, but its enormous economic growth had not been matched by an increase in federal resources, which were limited by a welter of archaic constraints. Bray Hammond writes:

To keep relations between the government and the economy “pure” and wholesome, tons of gold had to be hauled to and fro in dray-loads, with horses and heavers doing by the hour what bookkeepers could do in a moment. This, moreover, was not the procedure of a backward people who knew nothing better; it was an obvious anachronism to which, in keeping it tied around the federal government’s neck, a mystical virtue was imputed. Actually its only beneficiaries were handlers of gold and speculators in it.4

There had been no national currency since before the Panic of 1837. The nation’s finances had taken the Jeffersonian small-government path instead of the Hamiltonian strong-government system of managed debt, and had ended up plucked clean. State power had been exalted and federal power demeaned, and the federal government had come apart. Cobb and Buchanan’s systematic wasting of the Treasury had left the Jeffersonian-Jacksonian tradition bankrupted. The way was clear for the remaking of government along a Hamiltonian path—or possibly even Franklinian, since it necessarily entailed paper money, and lots of it.

With the slavery interest, which had been the hard core of resistance to a strong federal government, having decamped, Lincoln now asserted federal powers in a way that had never been politically possible.

In a desperate effort to fund the government’s short-term obligations as it went to war, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, a lawyer who was not a banker and was a hard-money man, reluctantly issued US Treasury notes. These quickly became known as “greenbacks”: the first federally issued paper money.

Greenbacks were not redeemable for gold or silver. They were what some economists call “fiat money”—money that is worth something because the government says it is. Conceived by Elbridge G. Spaulding, the congressman from Buffalo, New York, who introduced the Legal Tender Act, greenbacks were a radical experiment born of the desperation Buchanan had left behind. Bray Hammond suggests that they were in effect a bankruptcy settlement.5 Though not convertible to specie, they were legal tender, meaning that their acceptance was mandatory for all obligations of the federal government.

Gold was coming in from California, where it was being found in creeks and rocks. Gold was coming in from England, which had become dependent on US wheat after its own crops failed, again. The federal government took in the gold and paid out greenbacks, which carried no interest and bore no date of maturity. They were simply intended to pass from one hand to another, and never be redeemed, only replaced.

There was a model for the Legal Tender Act: New York’s free banking act of 1838, which dealt out money to the state’s banks based on the amount of state bonds the bank had purchased and placed on deposit with the state. It was a hard fight to approve the act in Congress, after years of hard-money fiscal orthodoxy had taught that paper money was a diabolical swindle. Many believed that, as Jackson had insisted, the Constitution forbade such a thing. Lincoln signed the Legal Tender Act on February 25, 1862, and the first notes went into circulation on April 5, after the government had gone a long three months without money; $150 million were printed, though $60 million replaced demand notes being withdrawn from circulation, leaving a net $90 million of new money. Two months later, Chase asked for, and received, another $150 million.

A greenback: the silver front and green back of an 1862 US dollar, with Salmon P. Chase’s picture.

The obverse was a silvery gray, and the reverse was all green, giving the new paper dollar its nickname. Chase put his picture on the one-dollar bill, and Lincoln’s on the ten.

There was, however, still a gold dollar in existence, so there were effectively two standards; the value of gold went up compared to the value of paper when the South won a victory, and down when the North won. The notes began depreciating, and after another $150 million were printed in the aftermath of Lincoln’s call for three hundred thousand more troops, they depreciated more.6

The banks had wanted the Legal Tender Act, and it was followed by the National Bank Act of 1863, which created a national banking system. That year Chase’s supporter John Thompson founded First National, the bank that subsequently became Citibank.* The banks took the greenbacks in from the government and they paid them out to customers; at least they had something to use for money.7

Greenbacks were popular. People wanted paper money; everyone was heartily sick of the patchwork system of privatized money issued by local banks, which was increasingly becoming irredeemable as the crisis of war deepened. Many newspapers wanted paper money and evangelized on its behalf. Now, for the first time since Jackson killed the Second Bank of the United States, there was a paper money that had the same value everywhere in the country. The new federal notes had the effect of knitting together the roughly two-thirds of the country’s population* who were still flying the United States flag, because everyone had a stake in the survival of the currency, which meant, in the survival of the Union.

The bills depreciated substantially but did not become valueless. By 1863, they were trading at 61 percent of their face value, not bad considering the convulsions that the economy had undergone in wartime and the unresolved problems of a dual gold/greenback system.8 There were only three issues of greenbacks, which were withdrawn from circulation at war’s end, but the changeover had happened: though the course was not smooth, from then on the United States was committed to having a national paper currency.†

Greenbacks were as much an assertion of federal power as they were an economic innovation. Unlike the Confederate States of America, the United States had a functional government. As the Union created itself as a war machine, more initiatives issued from the federal government. Congress authorized, and Lincoln signed, an income tax. The Treasury sold the banks large amounts of long-term bonds. The Homestead Act was put into place—something that the South had been strenuously opposed to but that now could pass in the absence of their obstruction of it, though free black people were excluded. The Land Grant Act apportioned land to public colleges across the country. The National Bankruptcy Act was implemented.9 The Yosemite wilderness was set aside as a national park. And spectacular new possibilities were opened up for corruption as vast amounts of Western land were granted to railroads, ushering in the age of the tycoons.

We will not attempt to replay the great conflict in these pages. For our purposes, we think of it as two successive, overlapping wars.

The first we could call the War of Southern Conquest, which was started in the expectation of a quick takeover of the US government by force. Its advance was quickly stopped, and it was definitively over by the time of the double Confederate losses at Gettysburg (July 3, 1863, which ended the South’s invasion of the North), and Vicksburg (the next day, which ended the South’s control of the Mississippi River). The Southern leadership—Jefferson Davis in particular—had no plan B, and it seems as though they wanted to prolong the misery as long as possible. Having committed to the total war that treason against the republic signified, expecting to pay the maximum penalty in the case of a Northern victory without a negotiated settlement, they dug in and continued fighting against a much larger, better equipped enemy, as the corpses mounted.

But they still had their slaves. And property rights in human beings still had multiple benefits, one of which was allowing the owners to avoid combat. After the Confederate Congress passed the first conscription act in April 1862, providing for three years of compulsory service (though one could hire a substitute), it passed on October 11 the so-called “Twenty Nigger Law,” which exempted from the draft one white man per plantation with twenty or more slaves—in order to guard against rebellion. Overseers were also granted exemption.10 It stimulated a wave of desertions, already ongoing, by the poor whites of the South, who were overwhelmingly the ones dying on the battlefields in support of slavery. A catchphrase was popularized that has persisted in subsequent conflicts: rich man’s war, poor man’s fight.

The Confederate regime acted very much like an occupier on its own territory, especially in those rugged pockets with fewer slaves and consequently less interest in defending slavery. To fund its military operations, it imposed “tax-in-kind,” giving army officers the authority to take anything they wanted in a government-sanctioned banditry—everything from the horse that pulled the wagon, to the ham in the smokehouse and the corn in the garden plot, to the cloth women had woven to make clothes for their children. By 1862 already in Davis’s Mississippi, crops were not being planted for lack of manpower and supplies. Young men were conscripted on pain of death into the Confederate Army where they were miserably treated; unlike their officer class, Confederate troops frequently went without uniforms, tents, shoes, or food, even in the war’s early days, though they were well-supplied with ammunition. Nor did it escape their notice that many planters were occupying themselves not with fighting so much as with blockade-running their cotton to market. What, then, united the South’s poor yeomanry with its wealthy elite? Why did perhaps as many as a million Confederate soldiers experience untold misery and mass death to fight for the rights of 347,525 slaveowners?

One dependable, long-term force that held the white classes together was a culture of negrophobia: the visceral fear of annihilation in the race war they were certain would follow emancipation. This deeply embedded, centuries-old belief was unsubtly stoked at every turn. The War of Southern Conquest was from the beginning portrayed as the defense of white women and children against conjectured mass violence by black marauders, stoked against whites by monstrous abolitionists. But there were also poor yeoman farmers who regarded the Confederacy as a plague on them. There were Union volunteers from every slave state, and even in hardcore Mississippi, Jones County announced its independence from the Confederacy.11

African Americans were entirely on one side in this war. But at the outset of hostilities, they weren’t allowed to fight. US law prohibited black soldiers from enlisting in the army (though there were already black sailors in the navy), and Lincoln did not at first attempt to change it, so African American volunteers were turned down. The war went badly for the North during this time.

Despite the South’s insistence that the “Black Republicans” would force abolition on them, Lincoln had never proposed to end slavery in the Southern states. He had begun by insisting that it was not a war about slavery, but to preserve the Union. But on September 22, 1862, prodded by Seward and Chase as the carnage dragged on, and as Frederick Douglass had been urging all along, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, followed by the definitive proclamation on January 1, 1863. It only applied to those enslaved in the seceded territories; Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Kentucky, Missouri, and the District of Columbia, as well as some occupied territories, continued to have slavery while remaining in the Union, with New Jersey using the euphemism of “apprentices.” But the Emancipation Proclamation transformed the meaning of the war.

Only after the North committed unambiguously to emancipation could the war be decisively won. Lincoln had not previously claimed to be prosecuting a war on slavery, but now that was unquestionably what it had become. This, then, was the second phase of the war, which we will call the War on Slavery.

Artist Francis Bicknell Carpenter, who painted an imagined scene of Lincoln reading the proclamation to his cabinet, wrote that Lincoln told him, “I felt that we had reached the end of our rope on the plan of operations we had been pursuing; that we had about played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game.” Why had Lincoln not started that way? According to Carpenter, Lincoln told him that “it is my conviction that had the proclamation been issued even six months earlier than it was, public sentiment would not have sustained it. Just so, as to the subsequent action in reference to enlisting blacks in the Border States. The step, taken sooner, could not, in my judgment, have been carried out.” In short, political will.12

Effective January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation’s effect was somewhat symbolic, since it did not apply to those still held enslaved in Union territory and mostly applied to areas the Union did not control, but it nonetheless marked a change in the purpose of the war. The Fire-Eaters had long charged that the North was planning to impose abolition on them. Now, for the first time, it was a policy goal. And in allowing for the enlistment and arming of black soldiers, the Emancipation Proclamation was not symbolic at all. “I further declare and make known,” it read, “that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

Lincoln’s game-changer came as a shock to the Confederates. What Patrick Henry warned against had finally happened: enslaved assets—the property whose value had governed every Southern political initiative since colonial days—were no longer legally recognizable as such. In a long message to the Confederate Congress on January 12, Confederate president Jefferson Davis—who was never president of a functional government, but was commander in chief of a losing war—denounced the “execrable measure” by which “several millions of human beings of an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere, are doomed to extermination, while at the same time they are encouraged to a general assassination of their masters.”13 Up till that point, the Confederate hierarchy had considered the possibility that a negotiated outcome to the war might yet result in a reunited nation on their terms. No more.

Slaveowners’ wealth had crumbled to dust. There would be no more securitizing Southern banks’ collateralized slaveholdings by Northern banks, nor would European lenders buy into enslaved assets that Washington had pronounced worthless. Lincoln had been the wheat candidate; Britain, which had suffered bad harvests and needed Northern wheat, was siding with the North despite considerable Confederate sympathy in Lancashire. Nor did France save the day for Jefferson Davis, as it had for George Washington; instead, with the United States otherwise occupied, France invaded Mexico in 1861.

The Emancipation Proclamation decommissioned the capitalized womb. Labor was no longer capital. African American children were no longer born to be collateral. Their bodies were no longer a better monetary value than paper. The US economy was no longer on the negro standard. Not only were the slaves emancipated; so was American money.

The Emancipation Proclamation and the coming of the greenback were concurrent and were intimately related. Once the enormous appraised value of the bodies and reproductive potential of four million people was no longer carried on the books as assets, dwarfing other sectors of the economy on paper and generally distorting the economy, the financial revolution of a national paper money was able to happen. The end of the slave-breeding industry was crucial to the remaking of American money.

This engraving depicting three enslaved laborers was used on several different Confederate notes.

The Confederacy, meanwhile, was not receiving gold from California or from wheat sales to Britain. Instead, it took in its supporters’ accumulated savings in gold and silver and in return, it gave them some seventy varieties of engraved notes, many of them bearing pictures of slaves working. Some had a written promise on the notes to pay them back with interest once the war was over. These notes were not usable to pay import duties; only specie and bond coupons were allowed for that. Among the many notes featuring the picture on this page was a one-hundred-dollar Confederate note issued at Richmond on December 11, 1862, whose hopeful legend promised an excellent rate of return: “Six Months after the Ratification of a Treaty of Peace between the Confederate States and the United States of America, the Confederate States of America will pay to the bearer on demand One Hundred Dollars with interest at two cents per day.” The back side of the bill was blank.

The South’s banks were forced to buy worthless Confederate bonds on pain of being labeled treasonous to the Southern cause, so they effectively had their assets confiscated by the Confederacy. Unsurprisingly, the Southern banking system did not survive the war.14 With it went the commercial network that had connected the South’s slave-driven finance with that of the rest of the country.

There was still money to be made by the intrepid. Cotton had become a cash market, attracting middlemen willing to take personal risk in pursuit of high profit. Despite the difficulty of shipping, the sky-high prices that cotton fetched encouraged farmers to keep planting it instead of food. After Joseph Acklen died on the Angola plantation in 1863, his widow, Adelicia (previously Isaac Franklin’s widow), is said to have slipped into Louisiana from Tennessee to negotiate the illegal sale of twenty-eight hundred bales of cotton to an English merchant for an exorbitant sum of gold, said to be $750,000 or more, which she subsequently collected in person in London.15

Despite the worthlessness of Confederate money, some people made a profit with it. When New Orleans was occupied by the Union in 1862, Julius Weis, a merchant in Natchez, managed to sell his firm’s inventory of ready-made clothing to Confederate soldiers for Confederate money, “which was then nearly at par,” he recalled. “I took $15,000 of this money and bought a piece of property in Memphis, which I sold after the war for a like amount of greenbacks.”16 Still having “faith in the ultimate success of the Confederacy,” he spent another $18,000 in Confederate money for “a fine-looking mulatto, to whom I took a fancy.”17

After the Southern rebellion began, the Lehman Brothers were well-positioned, having a New York office, and after the Union occupied the factorage capital of New Orleans in 1862, they established an office there. They became blockade runners, exporting such cotton as they could sneak out of the South.

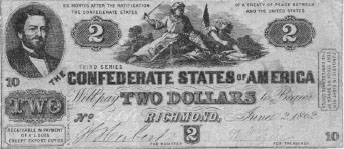

“Six months after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the Confederate States and the United States, the Confederate States of America will pay two dollars to bearer.” Judah P. Benjamin on an 1864 two-dollar Confederate bill, one of at least seventy issues of paper money during the Confederacy. Poorly printed, this note was cut out with scissors. The back is blank.

Blockade runners have been much romanticized, with tales of how they brought in British-made guns to the Confederates; but much of what the blockade runners brought back was luxury goods, because some of the wealthy continued to make money. After the war began, Charley Lamar became a blockade runner, slipping in and out of Charleston harbor on moonless nights in unlighted ships painted the color of water, past what Isidor Straus counted one night as twenty-one blockading steamers.18 The Strauses too went into blockade running. After a local grand jury excoriated what it called the “evil and unpatriotic conduct of the representatives of Jewish houses,” Lazarus Straus moved his family from Talbotton to Columbus, Georgia, the Confederacy’s second most important industrial center after Richmond, in 1863, when Confederate money was trading five cents to the dollar in gold.19

New Orleans’s Jewish community, tightly connected with that of Charleston, had perhaps doubled in size in the years preceding secession, and numbered about four thousand in 1861. Its merchants were clustered in the area of Canal Street, the dividing line between the town’s Anglo and Creole populations. It contributed the Confederacy’s most brilliant legal mind: Judah P. Benjamin, a St. Croix–born former sugar planter, former slaveowner, and a cosmopolitan attorney. He had been the second Jewish US senator (in 1852) and was a second cousin of the first Jewish senator, David Levy/Yulee, though neither he nor Yulee were practicing Jews. A key advisor of Jefferson Davis, he became the attorney general of the Confederacy, then its secretary of war, then its secretary of the treasury.

The role of Jewish merchants as financial intermediaries irritated General Ulysses S. Grant. “The Jews seem to be a privileged class that can travel anywhere,” he wrote to Assistant Secretary of War C. P. Wolcott in 1862. Then and today, this complaint of “privilege” was a central tenet of anti-immigrant rhetoric, with which Grant was unfortunately familiar, as his political background included a strong nativist streak and he had in the winter of 1854–55 briefly joined a lodge of the xenophobic “Know-Nothing” movement in Missouri.20

Grant’s General Order No. 11 of December 17, 1862, ordered the expulsion within twenty-four hours of all Jews “as a class” from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi. It was an attempt to stop cotton smuggling, but what it meant was that Jews who lived in those states were expected to pick up and leave their homes overnight. Grant’s order all too easily fell into a pattern of anti-Jewish language—some of it casual, some of it deeply believed—that fell on occasion from the lips and pens of antislavery figures that included William Tecumseh Sherman, William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Wilson, John Quincy Adams, and Henry Adams. It was the culmination of a series of measures that on November 10 had included an instruction to railroad conductors not to accept Jewish passengers. General Order No. 11 had a predictably demoralizing effect on the seven thousand or so Jewish soldiers in the Union army, subjecting them to taunts from other soldiers and causing one Jewish officer, Captain Philip Trounstine of the Fifth Ohio Cavalry, to resign in protest. A Jewish protest to Lincoln quickly resulted in the rescission of the order on January 6, 1863, and Grant subsequently apologized for having issued it.21

There were about three thousand Jewish soldiers in the Confederate army, most of whom were poor immigrants. Jewish merchants in the South, meanwhile, found themselves denounced in the Confederate Congress and on the receiving end of accusations from townspeople of disloyalty and extortion. The worse the war went for the South, the more vulnerable to scapegoating they were.

It is instructive to unpack the first words of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address again:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation …

Lincoln thus dated the republic as beginning eighty-seven years previously—not from the 1789 Constitution, but from 1776, though the Declaration of Independence does not mention a new “nation.” In affirming that the thirteen colonies were a nation in 1776 rather than a confederation of thirteen states, Lincoln was providing a revisionist take on the Declaration. He then attempted to reclaim the words of the Southern hero Thomas Jefferson:

… conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

With abolition now at last the official post-Emancipation Proclamation US policy, Lincoln was repudiating Dred Scott’s interpretation of Jefferson’s “all men,” declaring that the inspirational words might at last include those who had not been conceived in “Liberty.” At last, liberty no longer meant liberty for slavery.

Everybody knows what happened to Lincoln.

*In 1877, Thompson founded the bank whose successor still bears his friend’s name: Chase.

*Union population: ~23 million; Confederate: ~9.1 million (~5.1 million free, ~4 million enslaved).

†Convertibility to gold was restored in 1879, and ended under President Nixon in 1971.