Chapter 5

The Evolution of Exchange Rate Regimes and Some Future Perspectives

Paul R. Masson

University of Toronto, Rotman School of Management

5.1 Introduction

For the first time in about three decades, the international monetary system, and, in particular, the constellation of exchange rate regimes, seems to be under reconsideration. Since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of pegged but adjustable exchange rates in the early 1970s, global monetary relations have been subject to little official guidance or systematic control—apart from a few episodes of concerted intervention by the major powers. Countries are able to choose among the full range of monetary regimes from fixed to floating and are able to organize their monetary and intervention policies as they see fit. While the International Monetary Fund (IMF) continues to exercise surveillance over exchange rate policies and “exchange rate manipulation” is in principle ruled out by IMF guidelines, in practice, the major countries that do not need to borrow from the IMF can safely ignore its advice.

Indeed, laisser-faire in international finance has been the norm, leading some to term this an international monetary ‘nonsystem’. Unlike the gold standard period, or the Bretton Woods system before the United States closed the ‘gold window’ that assured convertibility for the US dollar into gold at a fixed price, there is no commodity anchor for fiat currencies. In the decades since the breakdown of Bretton Woods, the US dollar has lost more than 90% of its value against gold; over that period, a broader index of commodity prices has risen more than fivefold in terms of the dollar. At the same time, exchange rates for the major currencies fluctuate relatively freely and there have been large movements that reflect different monetary policies and economic conditions. The US dollar has experienced a trend depreciation against most other major currencies except the pound sterling. Global liquidity, constituted by international money in circulation in the form of currency issue and bank deposits, expands at a rate that depends on the uncoordinated actions of central banks and the demand for money by private individuals and firms.

In this nonsystem the US dollar continues to be the major international currency, that is, the currency used in international payments and official foreign exchange reserves, to denominate assets and liabilities, for pricing commodities, as anchor for pegged exchange rates, and as vehicle for trading other currencies. Its principal rival is the euro, whose introduction in 1999 marked a milestone in international monetary relations—the first creation by mutual agreement of a true multilateral currency. Nonetheless, the euro's current importance is considerably less than that of the dollar. Other currencies—principally the yen, the pound sterling, and the Swiss franc—have much more minor roles.

The challenge to the current laisser-faire system comes from the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and more generally, from the rise of other emerging market economies, whose newfound power is manifested in the virtual eclipse of the G8 by the G20. China, in particular, has advocated the replacement of the current system of uncoordinated expansion of international liquidity with one in which international agreement would control the supply of an international currency at the center of the system. In many respects, this proposal is similar to the role initially envisaged for the Special Drawing Right, namely, to become the “principal reserve asset for the international monetary system.”

In what follows, the history of currency regimes is briefly reviewed, including the years leading up to the breakdown of Bretton Woods, and then the experience post-1973 is examined. Numerous observers have noted that the current system has at times led both to high exchange rate volatility that seems unrelated to economic fundamentals and to exchange rate misalignments. At the same time, there has been a trend toward more freely floating exchange rates and toward monetary policies based on domestic objectives, typically, inflation targeting, which has successfully kept inflation in check in most countries. The possible role of exchange rate policies in contributing to international imbalances and the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 is the subject of active debate, and there is an emerging consensus that central banks need to include macrofinancial stability, as well as inflation, among their objectives. Nonetheless, the system has proved relatively robust and has allowed considerable discretion in the exercise of monetary policy autonomy.

This robustness needs to be kept in mind when evaluating the chances of a more managed international system taking its place. Much of the discussion of reform in the early 1970s, under the auspices of the Committee of Twenty and by academic economists, is still relevant at present. Those proposals for reform were not adopted precisely because countries were unwilling to abandon the monetary autonomy that a laisser-faire system afforded them. The last section considers whether the opportunity of strengthening the rules of the game of the international monetary system is greater now that the financial crisis has exposed fault lines in the current system. In the absence of fundamental reform, enhanced coordination among the major blocs is nevertheless possible, arguably necessary, to lessen exchange rate volatility and improve financial stability. It is argued that policy coordination should be organized around global public goods rather than conflict variables such as bilateral exchange rates or balances of payments.

5.2 A Brief History of Currency Regimes

Currency regimes, until recently, have relied on a link to a valuable commodity, usually gold or silver, to establish the value of a currency. While the monetary use of precious metals can be traced back to 2900 BC, this took the form of ingots whose value was based on weight (Eagleton and Williams, 2007, p. 16). Coinage seems to have emerged around 700–800 BC, when Lydian coins made of electrum (a naturally occurring mixture of gold and silver) were struck (Eagleton and Williams, 2007, p. 24). International exchange of currencies was normally based on their bullion value, whatever their value in tale (that is, their nominal value as officially declared). Exchange rates between currencies were thus relatively straightforward and stable—as long as countries linked their currency to the same precious metal and the currency was not “debased.” However, the classical gold standard period—when all the major powers linked their domestic currency's value to gold—lasted only from 1896 to 1914.

England was effectively on the gold standard starting in 1817, with silver coins becoming subsidiary currency whose value was established by fiat, not by their (lesser) bullion value (Chown, Chapter 7). However, during much of the nineteenth century, other European countries, the United States, Japan, and India variously had a silver standard or a bimetallic standard whereby both gold and silver coins were supposed to reflect their metallic content. However, the relative market price of the bullion content of gold and silver coins in any given country on a bimetallic standard could differ from the exchange rates implied by their nominal values. If the divergence was too great, this led to the operation of Gresham's law, in which the “bad” money, whose official value was greater than its bullion value, drove out the “good” money. As a result, countries on a bimetallic standard faced the prospect of either the gold or the silver coins disappearing from circulation, if the price of gold relative to silver differed significantly from the exchange rate implicit in the coinage.

From 1815 until 1872, the relative price stayed remarkably constant, fluctuating between 15 and 16 ounces of silver for one ounce of gold (Chown, 1994, Table 8.1). In most cases, these fluctuations were not large enough to provoke melting down coins for industrial or jewelry use. However, another channel for arbitrage was the shipment of currency to a country where it could be minted at a higher value. This made it important for the survival of bimetallism for countries to agree on the ratio and embody a common ratio in their coinage. This was the basis for the Latin Monetary Union; however, the attempt to reach agreement with other countries, including Britain, Germany, and the United States, at the Paris Conference of 1867 was a failure (Chown, 1994, Chapter 9).

Silver discoveries and the increased demand for gold because of the adoption of the gold standard by Germany in 1873 led to the breakdown of the Latin Monetary Union. Its members (France, Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium) subsequently went onto the gold standard, as did the United States in 1896 with its rejection of a silver standard (despite William Jennings Bryan's plea not to “crucify mankind upon a cross of gold”). Thus, until 1914, the world's exchange rate regime was simple and transparent since exchange rates between the major currencies, which were convertible into gold, were defined by their gold content. Nevertheless, currency values could fluctuate within a narrow range, defined by the “gold points,” which were the thresholds for profitable arbitrage between currencies. The operation of the gold standard is often considered to have removed discretion over monetary policy, but in fact, its operation was not really so automatic, as central banks used interest rate policy to attract gold and they issued bonds to prevent the money supply from increasing in response to gold inflows (de Cecco, 1974).

The classical gold standard came to an end with the outbreak of war in 1914; countries established limits on the convertibility of their paper currencies into gold as well as restrictions on gold movements abroad. Although most of the major countries resumed a link to gold during the 1920s,1 the system collapsed a few years later as a result of the economic downturn and banking crises of the Great Depression. Although the classical gold standard was widely thought to have contributed to the free movement of goods and persons and furthered global integration and prosperity (Keynes, 1920, quoted in Yeager, 1996), the system was clearly incompatible with the world economy of the interwar period, given the large accumulation of war debts and the desire to use monetary and fiscal policies to cushion the effects of the global downturn that began in 1929 (Cassell, 1936; Eichengreen, 1992).

The interwar gold standard was characterized by rivalry among key currencies, in particular, the pound sterling and US dollar, in their roles as vehicles for international trade and finance. Many smaller countries pegged to these currencies, rather than to gold directly. This regime is better characterized as a gold exchange standard since these currencies, which could be exchanged into gold, nevertheless carried out most of the functions of international money and other countries often held their reserves not in gold, but in the key currencies. Yeager argues that this attempt to economize on gold contributed to the precariousness of the system (Yeager, 1996, p. 80). When it broke down, exchange rates fluctuated in ways that were viewed as inhibiting adjustment, at times reflecting deliberate attempts to gain competitive advantage by overdepreciating one's currency. This period gave flexible exchange rates a bad name, and Nurkse, in an influential study done for the League of Nations, concluded that a return to fixed exchange rates was called for (Nurkse, 1944).

The 1944 conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, created the so-called Bretton Woods regime of pegged but adjustable exchange rates with the dollar at its center. Countries were expected to keep their exchange rates against the dollar within narrow margins, plus or minus 1%, and the United States assured convertibility of the dollar into gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. Exchange rates could be changed in cases of “fundamental disequilibrium,” to be monitored by the IMF, which could also provide financing to prevent adjustment from being costly in terms of output losses. Exchange rates of the major currencies did adjust, most notably, the pound sterling, which was devalued in 1949 and 1967, and the French franc, which was devalued in 1957, 1958, and 1969, while the deutsche mark was revalued in 1969. However, arguably, exchange rates adjusted too infrequently since devaluations were resisted due to the loss of face they caused and surplus countries were not constrained to adjust since there was no upper limit to reserves (Yeager, 1996).

Another problem with the system was the role of the center country, the United States, whose currency was the main component of international liquidity and other countries' reserves. Robert Triffin identified the dilemma facing the global economy: in order to supply international liquidity, the United States had to run balance of payments deficits, but these deficits undermined the credibility of the dollar, in particular, the commitment of convertibility into gold (Triffin, 1960). Balance of payments deficits led the United States to put restrictions on capital outflows and to close the gold window (i.e., abandon convertibility) to private holders in 1968, while putting pressure on foreign central banks to not redeem dollars for gold and finally, also closing the gold window to the latter in August, 1971 (as well as imposing an import tariff to put pressure for a readjustment of currency values). The Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, which appreciated other major currencies against the dollar and increased the price of gold, only succeeded in extending the life of the Bretton Woods regime until March 1973, when all other major currencies floated against the dollar (see Solomon, 1982, for a detailed history of this period).

In the meantime, considerable thought had been given to alternative international monetary systems in which the US dollar would be supplemented as reserve currency by multilateral liquidity creation and in which there would be greater symmetry in the adjustment of surplus and deficit countries. The creation of the special drawing right (SDR) was the main outcome of this process. The SDR gives the automatic right to have access to usable currencies, and was intended to address the Triffin problem mentioned above. However, by the time of the first SDR allocation in 1969, the problem was not a reserve shortage but a glut of US dollars. Thus, the SDR never came close to becoming the “primary reserve asset” of the international monetary system as intended by its creators.

Fundamental reform of the Bretton Woods system was further considered by the Committee of Twenty (representatives of the 20 countries with executive directors at the IMF), but proposals did not command sufficient agreement. Instead, this reform effort was abandoned and the system (or “nonsystem”2) that was created by the floating of currencies against the dollar was made official by the 1976 Jamaica Agreement. This allowed countries to choose any exchange rate regime ranging from a free float to a currency peg (but did not include a peg to gold, which was demonetized).

5.3 Performance of the Laisser-Faire Exchange Rate System, 1973–2010

The “nonsystem” inherited some of the perceived defects of the Bretton Woods system—no control over international liquidity and asymmetry in the need for adjustment of deficit and surplus countries—supplemented with much greater volatility of exchange rates and at times, large misalignments. At the same time, it allowed much more freedom in the use of monetary policies and no longer obliged countries to defend parities. The flexibility of exchange rates, which facilitated balance of payments adjustment, and the relative absence of rules of the game made the regime relatively robust. In principle, the IMF's Guidelines to Floating ruled out manipulation of exchange rates (for instance, to achieve competitive advantage), and the IMF's surveillance over exchange rate policies existed to rule out negative spillovers. In practice, however, no country was sanctioned for manipulation, and the IMF's advice mostly went unheeded by the major countries, which did not need to access IMF financing.

Assessment of whether the current regime is better or worse than the Bretton Woods system requires addressing two basic issues. First, has the greater flexibility (and consequent volatility) of exchange rates contributed to better balance of payments adjustment (and macroeconomic performance generally)? Second, would the alternative of maintaining fixity of exchange rates be feasible in a context of increasing global financial integration?

Regarding the first issue, since Mussa (1986), it has been recognized that flexible exchange rates have been associated with greater volatility in both nominal and real exchange rates. This might of course be due to larger shocks during the flexible rate period. However, work by Flood and Rose (1999) concludes that macroeconomic performance seems to be independent of the exchange rate regime—calling into question whether the greater exchange rate volatility since 1973 helped damp the volatility of real variables. Clearly, exchange rate movements not only just serve to achieve macroeconomic adjustment but also induce unneeded fluctuations in international competitiveness.

As for the second issue, the feasibility of a pegged rate system in the present day world, its very breakdown in 1973 is prima facie evidence for a negative answer. But Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1994), who analyze the changes in international monetary regimes starting with the pre-World-War-I gold standard, conclude that it is difficult to identify the causes for the breakdown of Bretton Woods system, as neither increased shocks nor reduced macroeconomic flexibility were present. Subsequent exchange rate crises affecting pegged or quasi-fixed exchange rates (the European Monetary System (EMS), Mexico, and Asian emerging markets) confirm the fragility of pegs in a context of high capital mobility and provide strong evidence that reestablishing Bretton Woods system would be impossible. But this leaves open the possibility that a regime of managed floating—intermediate between pegged rates and free floats—might not be both feasible and superior to the current one, producing both balance of payments adjustment and lower exchange rate volatility.

The costs of currency volatility have been hotly debated. Despite a presumption that volatility should have a negative effect on trade, a careful look at economic theory gives an ambiguous answer, and early empirical work suggested that effects in any case were small (C té, 1994). More recently, interest in this issue has been revived by striking results found by Andrew Rose and others (Frankel and Rose, 2000; Rose, 2000) that trade within currency unions is much greater than the standard gravity model would suggest. Some of this effect seems to come from lower exchange rate volatility, although some is specific to currency unions themselves (Carrère, 2006).

té, 1994). More recently, interest in this issue has been revived by striking results found by Andrew Rose and others (Frankel and Rose, 2000; Rose, 2000) that trade within currency unions is much greater than the standard gravity model would suggest. Some of this effect seems to come from lower exchange rate volatility, although some is specific to currency unions themselves (Carrère, 2006).

The post-1973 period has, in fact, been characterized by an intensification of economic globalization—despite the fears that exchange rate variability would limit trade and foreign direct investment. As a result, there has been an increase in trade relative to GDP and an even larger increase in cross-border capital flows. Increased economic integration has had a number of causes: (i) technological innovations that have lowered communication and transportation costs; (ii) successive rounds of trade liberalization; and (iii) the inclusion of former communist countries into the world trading and financial system. Increasing capital market integration has also benefited from the introduction of new financial instruments (derivatives, swaps, and forwards) and a reduction in the official barriers to capital flows.

This increased economic integration has had at least three, sometimes conflicting, influences on the global economy. First, it has increased market discipline over government policies, making policymakers more conscious of the need to put their houses in order. Second, it has at times stimulated the perceived need for policy coordination across countries to mitigate unfavorable spillovers. Third, it has helped bring the richer developing countries (“emerging market economies”) into world financial affairs, while making them more vulnerable to currency crises.

5.3.1 Market Discipline

Financial integration has made the discipline of the market much more stringent. With increased cross-border capital movements, the government cannot rely on a captive market to sell its debt. Flexible exchange rates move quickly to reflect concerns about monetary policy credibility, as was especially evident during the EMS crisis of 1992–1993 and the subsequent emerging market crises. The 2010–2011 euro zone sovereign debt crisis shows that cross-border market discipline can also be exerted strongly in a common currency area. The response of the major industrial countries has been to try to make their monetary and fiscal policies more transparent and sustainable. Inflation targeting has been one manifestation of this, and improved budgetary procedures another. The same forces have been exerted on those emerging market countries that have liberalized their capital accounts, with similar results.

The one notable exception is the United States. Continued demand by other countries for US dollar assets for liquidity purposes and as official foreign exchange reserves has allowed that country to run persistent current account deficits financed at low rates of interest. As a result, the United States is the world's largest net debtor, with a negative net international investment position in excess of $2.7 trillion, about 20% of US GNP.

5.3.2 Economic Policy Coordination

At the same time, the negative spillovers of unsustainable policies and a recognition that the market does not always get it right led to the formation of the G5/G7 in the 1970s and to episodes of policy coordination involving exchange rate intervention and jointly agreed packages of macroeconomic and structural policy measures (Funabashi, 1988). The high points of intervention policy were the Plaza Agreement and Louvre Accord of 1985–1987 to correct the overvaluation of the US dollar and to bring about its subsequent stabilization. The 1978 Bonn Summit also involved a major attempt to coordinate fiscal policies.

Greater coordination of monetary policies has also taken the form of regional agreements. The EMS, created in 1979, aimed to create monetary stability in Europe in the face of global exchange rate instability. It was dealt a major setback in the 1992–1993 EMS crisis, leading to a widening of the bands of fluctuation to ± 15% around central parities. It did, nevertheless, help prepare for monetary union. The successful launch of the euro in 1999 has not created the preconditions for macroeconomic policy coordination in Europe that many had hoped, due in part to the failure of the Stability and Growth Pact to exert budget discipline. The sovereign debt crisis affecting Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain that broke out in 2010 led to a recognition that euro zone institutions would have to be strengthened.

In Asia, the Chiang-Mai Initiative aims to achieve monetary integration among ASEAN countries, plus China, Japan, and Korea. At present, this takes the form of swap agreements among the region's central banks, but it may proceed to greater exchange market intervention, target zones, and even a common currency. Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America also have various projects to strengthen regional monetary integration.

5.3.3 Integration of Emerging Market Countries into the Global Economy

Financial integration of developing countries has gone through three phases since 1973. The first phase involved the recycling of petrodollars to developing countries by banks, but with inadequate safeguards to ensure that the recipient countries were investing the funds wisely and would be able to repay their debts. This led to the “lost decade” of the 1980s, when developing countries defaulted and were denied further access to nonofficial lending. The second phase, following the replacement of most of the remaining bank debt by Brady bonds, ushered in a period of major expansion of market-based sovereign bond issues by emerging market countries. This phase was also accompanied by a series of crises, starting with Mexico in 1994, followed by Asia in 1997–98, Brazil in 1999, and so forth. The strength of discipline (for good or bad reasons) that financial markets could exert was brought home to these countries. The third phase was in part a response to the currency crises and was accompanied by major reforms to reduce emerging market countries' vulnerability. These reforms helped align their policies with those of the advanced countries and involved accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, strengthened financial regulation, and improved macroeconomic policies. For instance, a number of countries ranging from Mexico, Brazil, and Indonesia were led to adopt exchange rate flexibility and inflation targeting. At the end of 2010, developing countries held two-thirds of the world's foreign exchange reserves, reversing their share relative to advanced countries of a decade before.

5.4 Trends in Currency Use

The currency crises of the EMS, Latin America, and Asia highlighted the fragility of adjustable peg regimes in the context of liberalized capital accounts. This led some to argue that, in fact, only two polar exchange rate regimes were sustainable—namely, a pure float and a hard fix, such as a currency board or a monetary union (Eichengreen, 1994; Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1995). All the intermediate cases of exchange rate regimes, including adjustable pegs and managed floats, were viewed as ultimately condemned to disappear. To quote Eichengreen (1994, pp. 4–5), “… contingent policy rules to hit explicit exchange rate targets will no longer be viable in the twenty-first century … [C]ountries will be forced to choose between floating exchange rates on the one hand and monetary unification on the other.” This theory was called the “two poles” or “hollowing out” hypothesis. It was supported by the well-accepted proposition that countries had to choose at most two among the following three policy objectives, which taken together, were inconsistent: (i) monetary independence; (ii) a pegged exchange rate; and (iii) capital mobility.

Others objected that countries could still choose to trade off one of the policy objectives for the other two and that, moreover, the choice was not all or nothing (Frankel, 1999). For instance, some limits on capital mobility might afford a country some monetary independence even with a pegged exchange rate. Moreover, countries could manage their exchange rates to some extent, without attempting to defend a pegged rate. And countries willing to give up all monetary independence could credibly maintain a pegged rate, despite high capital mobility.3

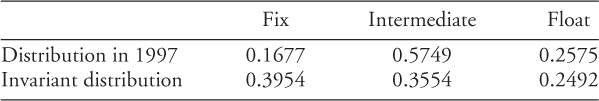

The classification of exchange rate regimes is subject to much controversy; but the different classifications will not be discussed here. The IMF's revamped classification, reported in the table below, suggests some increase in hard pegs (countries with no separate legal tender and those with currency boards) and floating arrangements and decline in soft pegs over 1996–2007. However, the floats include both managed and independent floats. If we include the former with soft pegs in intermediate exchange rate regimes, as is appropriate, then the trend toward hollowing out of intermediate regimes is modest, at best. In 2007, intermediate regimes still constituted the largest category, prevailing in 130 of 188 countries (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Evolution of Exchange Rate Regimes

A formal test of hollowing out using Markov-switching regimes (Appendix A) does not support the disappearance of intermediate regimes. It is true that pegged rate regimes seem to have a limited life span, but this does not preclude countries adopting them for temporary stabilization purposes. History suggests that it is better to think of countries occasionally altering their regime in response to changing circumstances, rather than choosing once and for all the regime that is right for them and keeping that regime for eternity. For instance, adjustable pegs have been chosen by countries facing strong inflationary pressures in a context in which the central bank did not have a great deal of credibility; this policy has been called “exchange-rate-based stabilization.” A peg to a stable international currency helps to shore up credibility and to provide a transparent and easily monitored policy rule. While the adjustable peg may not be sustainable forever, it may nevertheless serve as a useful temporary regime for reducing inflation quickly, and it is unrealistic to expect that the circumstances that made such a policy useful in the past will not recur.

This is confirmed when the matrix P of transition probabilities between exchange rate regimes is endogenized using explanatory variables suggested by theories of voluntary and involuntary exits from regimes (Masson and Ruge-Murcia, 2005). Voluntary exits can be explained by optimal currency area criteria, while involuntary exits are those that are consistent with the currency crisis literature. The transition probabilities pij (the probability of transition from regime i to regime j) are allowed to vary over time and made functions of a vector of explanatory variables X:

5.1

The variables in X include inflation, trade openness, GDP growth, and the level of reserves divided by GDP.

Estimation results are different for developed and emerging market economies. The stock of reserves helps explain (inversely) the transition between fixed and intermediate regimes for emerging market countries, but not for developed economies, which do not seem to be constrained by their reserve levels. Low growth helps to explain the transitions from intermediate to floating rate regimes for developed countries, while for emerging economies, high inflation explains transitions both from fixed to intermediate and from intermediate to either fixed or float. This is evidence both of the use of exchange-rate-based stabilization and the ultimate need to exit the peg once cumulated inflation makes a peg untenable.

Thus, poor macroeconomic performance—both low growth and high inflation—leads to changes in policy regime. In response to severe shocks, countries tend to abandon their current policy frameworks and search for alternatives. This was true even of regimes as “iron clad” as the gold standard in the 1930s or Argentina's currency board and convertibility plan, which it exited in 2002. By analogy, one might expect that countries would explore a move back to greater exchange rate fixity if financial turmoil under floating exchange rates became too severe.

5.4.1 Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009

While the evolution of the laisser-faire monetary system over its first three decades was accompanied by frequent financial crises affecting developing countries, the advanced countries were largely spared after the EMS crises of 1992–1993. This scenario changed in 2007 when problems in the US subprime mortgage market threatened the banking systems in all the major countries through their holdings of complicated and opaque structured products. While the crisis had many causes, the financial excesses were at least in part fueled by excessive global liquidity and the large current account deficits of the United States that were financed by the buildup of holdings of US assets by foreigners—especially China, whose pegged exchange rate and large current account surpluses forced it to accumulate foreign exchange reserves. By 2010, these amounted to more than two and a half trillion dollars and were still rising.

The crisis highlighted the fundamental absence of control over global liquidity and the lack of pressure on the United States to adjust its macroeconomic policies in order to “live within its means”—that is, to limit its current account deficit and prevent further increases in its indebtedness to foreigners. These deficiencies inspired renewed interest in reform of the international monetary system, with proposals by the BRIC countries to move toward a more managed system with a multilateral reserve asset (Dailami and Masson, 2010). In the following section, the author discusses the prospects for reform and speculates on the evolution of exchange rate arrangements.

5.5 Prospects for the Future

The future of exchange rate regimes may be influenced by two distinct types of events. In the context of the current system, or rather “nonsystem” where exchange rate regimes are virtually at the discretion of individual governments, any regime from a pure float to a hard fix is possible—as are regional currencies and dollarization. In light of the experience of the past 40 years, competition among currencies is likely to dictate the choice of international money. However, it is also possible that there might be a concerted move to a different global system—a more managed international monetary system in which the choices of individual countries were constrained and in which the “rules of the game” were made more stringent. Past examples of the latter include, of course, the gold standard and the Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable parities, but neither seems likely to be reinstated. Instead, any new system is likely to allow countries to retain considerable flexibility to hit domestic objectives. This is discussed further below, and modifications to the current system are suggested.

5.5.1 The Current System

For reasons that have already been discussed, short of a concerted reform, it does not seem likely that the world will converge to a single system, in which all countries let their currencies float freely, despite the arguments of the proponents of such a regime accompanied by inflation targeting (Rose, 2006). The advantages of such a regime have been overstated by its proponents: neither is it true that policy coordination is redundant if all countries adhere to this regime nor does its single-minded focus on inflation to the neglect of financial stability and the risk of asset bubbles seem desirable, especially in the light of the recent global financial crisis. Indeed, a world of exchange rate flexibility and inflation targeting faces two severe problems. First, there is no control over global liquidity, which is the result of the uncoordinated decisions of the central banks issuing key currencies, and this may lead to global asset bubbles or global deflation. Second, exchange rate volatility and misalignments may, at times, be excessive and require a credible commitment to resist them by modifying the policies of systemically important countries. Both these problems require reinforced policy coordination to make the current system work better, and the formation of the G20 and the statements of its leaders indicate agreement, in principle, on the need for greater coordination, if not a road map of how to achieve it.

Another aspect of the current system that can exacerbate the two problems mentioned above is competition for the role of key currency. At present, it is the US dollar that plays this role in most of the uses of an international currency such as in other countries' foreign exchange reserves (where its share is currently about 64%), as a vehicle currency for forex trading (where the dollar is one of the two currencies used in 85% of all global trades), in trade invoicing, in denominating international debt (although the euro is a serious rival here), etc. There has been much speculation, however, that the decline of the dollar, fueled by high US indebtedness to foreigners and continuing large budget deficits, will lead to a much more multipolar international monetary system, with other currencies rivaling the dollar. Chinn and Frankel (2008), for instance, argue that in the coming decade, the euro is likely to take over the top spot, while Persaud (2007) suggests that in the not too distant future, China's renminbi will reflect the importance of China in the global economy—and China's GDP is slated to become the world's largest within a decade or two. Others are sceptical that the economic and political factors that have led to the dollar's dominance will go away, including the dynamism of the US economy in technological innovation, the importance of the US for global security, and the existence of deep and broad US financial markets supported by an independent central bank and a liquid market in Treasury securities (Cooper, 1973; Helleiner, 2009; Posen, 2008). In fact, the euro has disappointed some of its proponents and has so far mainly served as a regional currency, not an international one (ECB, 2010). As for the renminbi, it has virtually no international role at present, and China requires further major liberalization of its capital account, exchange rate flexibility, and domestic financial reforms before the renminbi assumes one (Dobson and Masson, 2009).

The creation of a more symmetric, multipolar world monetary system with several key currencies may lead to greater instability, as countries attempt to exert their power and rivalry for the advantages that a global currency brings. In the years leading up to the creation of the euro, there was already concern that a Europe that was more unified and less open to the outside would make policy coordination more difficult (Alogoskoufis and Portes, 1997). Consistent with the theory of hegemonic stability (Kindleberger, 1973), the lack of a global hegemon in the future may threaten stability of the international monetary system (Cohen, 1998, 2000). In fact, trade within regional blocs has continued to grow faster than trade between blocs, suggesting that the forces toward regionalism are outpacing those for globalization. Blocs that are relatively closed to the outside world can more easily use trade protection as a policy weapon to achieve their goals because they are less vulnerable to retaliation. On the monetary front, the example of the euro has led to other projects for regional currencies. They include proposals for common currencies among the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, several regional groupings in Africa, MERCOSUR, and the countries of East Asia grouped together in the Chiang Mai Initiative. While these other potential regional currencies have considerably less institutional backing at present than does the euro zone, a world with fewer currencies than the present seems a likely outcome a decade or two later. Strengthening of regional blocs may exacerbate the problems facing the current laisser-faire international monetary system and lead to calls for change.

5.5.2 Toward a more Managed International Monetary System?

The challenge to the role of the dollar may come not from other national currencies, but from the move to a new monetary system in which countries agree to vest responsibility for the control of international liquidity to a global body and take it away from national central banks (Dailami and Masson, 2010). Such a system—which revives Keynes' notion of a world reserve bank—would seem to be the ultimate objective of the proposal by the BRIC countries to increase the attractiveness of the SDR in international financial markets. The SDR, when it was created in the late 1960s, was intended to become the primary reserve asset of the international monetary system—a role that it has never played. Even after the agreement in 2009 for a general allocation to augment the stock of SDRs by $250 billion, they still represent only 4% of global foreign exchange reserves. After a brief flurry of issuance of SDR-linked private securities three decades ago, the private SDR market has become virtually moribund and pegs to the SDR currency basket have also almost disappeared. Thus, the BRIC initiative to revive the importance of the SDR seems a long shot indeed.

More seriously, for the chances that the SDR would replace the dollar and other national currencies in international use, the SDR neither has proved a very attractive reserve asset nor is it a currency on its own—just the right to draw other usable currencies. So issuing more SDRs would not change the amount of national currencies in circulation. While the SDR in its current form could be made into a world currency if governments decided at some stage that they were willing to do so (as EU countries were willing to do for the ECU, which was a basket of currencies that became the euro), the leap required would be enormous. It would presuppose agreement to create in effect a world central bank, which in order to gain legitimacy would itself require strengthening of other global institutions. The prospect of any such agreement seems many decades away, if at all conceivable.

In what other ways could the rules of the game be modified in order to constrain national governments more strictly with the aim of ruling out some of the excesses that were discussed above? It seems clear that ad hoc coordination of policies, whether to intervene in exchange markets (such as those embodied in the 1985 Plaza Agreement) or occasional bargains to modify macroeconomic or structural policies (such as the 1978 Bonn Summit) are not sufficient; they are too dependent on the vagaries of domestic politics and the personalities of those who happen to be in power at the time. There are at least three types of policy rules with automatic triggers that could be envisaged instead: (i) rules on allowable exchange rate behavior; (ii) limits on balance of payments positions; and (iii) criteria for proscribing beggar-thy-neighbor macroeconomic policies.

Exchange Rate Rules

The Bretton Woods system prevented countries from gaining competitive advantage by engineering depreciations of their currencies, unless a “fundamental disequilibrium” of their balance of payments was present. In contrast, in a world of generalized floating, the opposite problem arises: a country should not be able to achieve a position of competitive advantage by preventing the operation of market forces on its currency's value. This was the objective of the Guidelines to Floating, adopted by the IMF in 1977; it proscribed “currency manipulation,” which could be identified (in principle) by evidence of prolonged one-way intervention in exchange markets. In practice, the Guidelines have not been applied—even in the most obvious case of China, which has intervened massively throughout the past decade in the face of enormous current and capital account surpluses, leading it to accumulate the largest foreign exchange reserves ever. The system could be reformed to make the Guidelines effective, for instance, by prescribing penalties that could take effect automatically. As an example, currency manipulation could lead to countervailing duties being authorized by the WTO.

In effect, the current “anything goes” system where all exchange rate regimes are permitted would be considerably narrowed if currency manipulation were ruled out. It is important to understand that all fixed rate systems face periods of sustained one-way intervention; this is true because shocks are serially correlated and their effects are also persistent. This helps explain why the Europeans have never been keen on applying the Guidelines to Floating, because the EMS faced extended periods of speculative attacks against its central parities, and politicians and central bankers used a variety of policies, including intervention, to resist them. A stringent prohibition of one-way intervention would effectively achieve the “hollowing out” of intermediate regimes that its proponents have claimed market forces will eventually do. It would virtually rule out adjustable pegs and impose severe limits on “managed floats.” Presumably, currency boards could still be allowed to operate on the presumption that the self-equilibrating changes in the domestic money supply would rule out prolonged one-way accumulation or decumulation of reserves (although the experience, e.g., of Argentina, makes that presumption questionable). So, in effect, it would produce a world in which all currencies floated more or less freely.

As argued above, countries use exchange-rate-based stabilizations because, as a result of large external shocks or policy errors, they want to achieve rapid disinflation and shore up the credibility of the domestic monetary authorities. Ruling out currency manipulation would eliminate this option. While a case might be made that it was desirable to do so, some countries nevertheless would object to any reform of the system along these lines. In any case, a problem arises for the system not so much from exchange-rate-based stabilizations, but rather when countries maintain an undervalued exchange rate to stimulate exports and growth. Obviously, the size of a country matters, and it may be thought that the problem of China should be treated as a one-off since the Chinese authorities have indicated their willingness to embrace greater exchange rate flexibility.

Another type of exchange rate rule would put in place a form of managed floating subject to specific rules designed to combine exchange rate flexibility with measures to prevent excessive volatility and misalignments of currency values. This could take the form of a system of “target zones” for exchange rates—a proposal most closely associated with John Williamson (Williamson, 1993). There are two key elements for its successful operation: agreement on a consistent set of exchange rate targets and effective tools for hitting those targets. On the one hand, countries (and experts) have often disagreed on the “fundamental equilibrium” exchange rates. On the other hand, intervention to defend depreciating currencies alone in the presence of freely mobile capital is likely to be ineffective. A successful system also needs to impose policy adjustments on the appreciating currencies, but it is much more difficult to get their agreement to do so.

Given these difficulties, one could envision relaxing the requirement to maintain exchange rates within narrow margins. However, widening the bands, as was done in the EMS, or making the ranges “soft bands” rather than fixed limits, detracts from the stabilizing benefits of operating a target zone system. Therefore, short of reducing the mobility of capital, it is unlikely that a formal target zone system would be put in place as part of a fundamental reform of the international monetary system (although a de facto grid of what are judged to be equilibrium exchange rates may at times embody a consensus of official views and guide ad hoc currency intervention).

Balance of Payments Rules

The economic spillovers between countries operate mainly through their balances of payments. Moreover, exchange rate misalignments and inappropriate domestic policies (such as a tax system that discourages saving) can be expected to show up in imbalances in the current account. Hence the interest in using some measure of external payments disequilibrium as a trigger for policy action by the country concerned. This was widely discussed by the G5/G7 and international organizations in the 1970s and 1980s (Frenkel et al., 1990) and was recently revived in a proposal to the G20 by the US Treasury Secretary, Timothy Geithner4 A country's current account surplus of deficit would be limited to some proportion of its GDP, say 4%. If it exceeded that threshold, the country would have to take policy measures to bring it back within the allowable range.

The earlier consideration of such rules, inspired in part by US current account deficits and Japanese surpluses in the early 1980s highlighted the importance of understanding the source of the current account deficits or surpluses. Deficits can be the result of inadequate saving (including fiscal dissaving) or, instead, a result of unusually attractive investment opportunities. Imbalances are the outcome of the complex interaction of government policies and private sector behavior; a closer analysis is needed to come to a judgment concerning the causes and whether there is reason for concern. Hence the difficulty in coming up with a rule that would link an indicator variable with policy action. So it is hard to imagine a rules-based international regime along these lines, although current account indicators could well be a trigger for international discussion and further analysis.

Another type of balance of payments rule might be to impose a system of constraints on capital movements or on the stocks of foreign assets and liabilities. One could, for instance, prevent countries from acquiring foreign currency debt in excess of their foreign exchange reserves. This proposal was made by Morris Goldstein (Goldstein, 2002), as a way of reducing the likelihood of emerging market crises. Another possibility would be to prevent accumulation of reserves beyond a certain amount (based on underlying characteristics of the economy, such as GDP, imports, etc.). This would address a concern that the current system (and Bretton Woods system before it) apply asymmetric pressures to adjust on surplus and deficit countries: the latter are forced to adjust since there is a floor to reserves, while the former can, in principle, accumulate unlimited reserves and postpone adjustment indefinitely. Rather than forcing exchange rate flexibility on China, a ceiling on reserves would allow it to choose from the array of policy changes those that it felt would be preferable to avoid the “prolonged one-way intervention” that led to the further accumulation of reserves.

Finally, one could imagine a change in the rules of the game that led to a world in which certain types of capital movements (such as short-term flows) were systematically constrained using capital controls or Tobin taxes—whatever the balance of payments position. While possible in principle, a systemic reform to turn back the clock in this area seems politically unlikely, given the trend toward liberalization, and hard to enforce, given advances in communications technology and the explosion of derivative financial instruments.

Macroeconomic Policy Rules

International policy coordination in the post-1973 world has ultimately been about the underlying macroeconomic policies, rather than about their symptoms—values taken by exchange rates or balances of payments. However, countries have rarely been able to reach agreement on coordinated policy packages. Could one formalize a set of rules for macroeconomic policies in a way that would limit payments imbalances and excessive exchange rate movements? For instance, countries that operate inflation targeting regimes can be evaluated on whether their inflation target is appropriate (most developed countries aim for a range around 2%, but developing countries have higher targets), and how successful they are at meeting their targets. Fiscal policies are more complicated since they have many dimensions: the level of tax rates, their progressivity, the size and composition of government spending, etc.). An overall measure of the stance of fiscal policy, however, is the fiscal deficit or surplus (perhaps corrected for the cycle). One could formulate an acceptable range for the fiscal position. Countries going outside that range should make policy adjustments to bring the fiscal position back inside the range.

However, the experience of international economic policy coordination since 1973 has shown how complex it is to analyze monetary and fiscal policies. While monetary policy is simpler to evaluate than fiscal policy, there is considerable uncertainty about future inflation. Moreover, monetary policy is not unidimensional: the inclusion of financial stability as an objective makes an assessment of the appropriate level of interest rates much more difficult. As for fiscal policy, the euro zone's attempt to use the fiscal deficit as the sole indicator of the appropriateness of policies has been an abject failure. While this failure has had a number of causes, it underscores the fact that fiscal policy has many objectives and is typically driven by a political process that is hard to constrain.

During the 1990s, the IMF's policy conditionality moved more and more toward detailed conditions on fiscal and structural policies for the countries that borrowed from it. In contrast, those that did not, including the major developed countries as well as the surplus countries such as oil exporters and China, could ignore the IMF's advice proffered in the context of annual Article IV examinations and the semiannual World Economic Outlook. A backlash against detailed macroeconomic policy conditions led the IMF in 2007 to refocus its surveillance on exchange rates. However, this had little effect, since surveillance over exchange rate policies has no more teeth than it had before.

Time will tell if the G20's attempt to exert peer pressure on its members' policies (the mutual assessment process (MAP)) will have more effect, but the current dispute over exchange rate levels and current account imbalances illustrates the problem with trying to get agreement on targets for variables that are inherently zero-sum—that is, have a beggar-thy-neighbor aspect. When there is a global shock (inflationary or deflationary), countries would all like to move their exchange rates and/or current accounts in the same direction, either to stimulate demand or to dampen inflationary pressures. The rules of the game of the gold standard or Bretton Woods proscribed this, but nothing similar exists at present. Unless the international rules of the games are reformed, or national policy regimes focus on variables that are international public goods, the G20 will only provide a forum for ad hoc coordination when the situation facing countries is sufficiently different that they can agree to policies that do not simply shift a problem from one country to another.

5.5.3 How and When Will Reform Occur?

It seems certain that the international monetary system will evolve—in some direction or other. We have sketched out some of the possibilities for new rules of the game that could be agreed to in principle by all countries, or at least by a sufficiently large number of countries to enable imposing these rules on other countries. Past experience suggests, however, that the rules of the game are rarely negotiated, but are rather more often adopted unilaterally by countries as a response to the occurrence of a crisis or even more dramatically, to the breakdown of the existing system. They may then be codified by formal agreements that make them into the accepted “rules of the game.”

For instance, the Paris Conference of 1867 aimed to extend bimetallism to the international monetary system, but it failed, and in another decade, the Latin Monetary Union had in effect disappeared as all the remaining major countries switched to the gold standard. The Genoa International Monetary Conference of 1922 passed resolutions to establish an institutional framework for cooperation to make the gold exchange standard work, but these resolutions were not adopted by the governments themselves. By the early 1930s, the system had broken down, and flexible exchange rates prevailed through the World War II.

The partial exception, of course, was the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, which created a universal system5 with clear rules of the game. However, this was achieved in very special circumstances. Only two countries—the United States and the United Kingdom—were in a position to call the shots, and in the end, it was only one that did so. Moreover, the Bretton Woods system, although it lasted almost three decades, eventually succumbed to market forces. It was patched up by the Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, hailed by President Nixon as the “greatest monetary agreement in the history of the world,” but this lasted barely 2 years. In 1973, there was generalized floating of the major currencies, which emerged when the countries concerned refused to acquire further dollar reserves and to maintain their currencies within margins of agreed parities.

Only a severe crisis is likely to lead to a negotiated reform of the international monetary system of major proportions, and even then, as the Smithsonian Agreement has shown, it may have a very short shelf life. Thus, if one had to speculate on the circumstances likely to trigger reform in the future, it seems more likely to be the result of a series of minor changes—some of them perhaps agreed incremental changes to the rules of the game, others taken unilaterally by a sufficient number of countries—leading to a new regime whose evolution was not completely planned nor foreseen.

5.5.4 A Global Nominal Anchor?

Given the difficulties in reaching agreement on broad-based international monetary reform, it is worth exploring how market forces could encourage de facto coordination of policies. As suggested above, countries should try to coordinate around “international public goods” rather than “conflict variables,” examples of the latter being the exchange rate and the current account. Problems with the latter variables occur at the time of major crisis, when a global shock makes all countries want to see these variables move in the same direction, but by their very nature, a gain for one country is a loss for others. Rules of the game could be devised to rule out using these variables at the expense of others, such as a pegged rate system, but as discussed above, a return to a Bretton-Woods-like system is unlikely.

One common objective of countries is control over inflation, and this helps explain the popularity of inflation targeting monetary policy regimes. But experience has shown that success in meeting inflation objectives (even when countries aim at the same target level of 2%) neither ensures exchange rate stability nor rules out beggar-thy-neighbor behavior. It may be worth considering moving away from national inflation targeting to a regime in which countries target the same basket of goods (and possibly services). If each of the issuers of key currencies committed to stabilizing the value of a basket of international goods and services in terms of its own currency, this would also stabilize their bilateral exchange rates. Most practical would probably be an index of prices of commodities that were actively traded, but it could also be a broader measure of inflation. Note that such a regime would not be equivalent to targeting domestic inflation (or the price level) since the basket would not be limited to a country's own goods and services but rather key off international prices. The fact that several key currency countries could target the same basket would allow coordination of policies to emerge naturally, without detailed agreement except on the composition of the basket (each country would target the same average price, but expressed in its own currency).

Note that this proposal concerns the key world economies, not the commodity exporters. Frankel (2011) proposes that each of the latter should target its export price. But since that price (in dollars, say) would be largely exogenous, targeting the domestic currency value of the export commodity would transmit the exogenous fluctuations in its dollar price to the country's dollar exchange rate, inducing an appreciation when the commodity's dollar price was high, and the converse when it was low. It would do nothing to stabilize the bilateral exchange rates of the key currencies themselves or the value of a basket of commodities.

By targeting an international price basket, the United States could enhance the attractiveness of the dollar as a key currency and assert its role as a global leader. It might induce other countries to do the same thing and thus promote global exchange rate stability through currency competition. Rather than achieving a managed international monetary system by a negotiated “big bang,” this would occur through the voluntary and unilateral policy moves of the major countries. In these circumstances, smaller countries would also find it in their interest to target such a basket. If all countries successfully maintained their currency values in terms of the same price index, their exchange rates would effectively be stabilized within narrow ranges.

Such a system would have the advantage of moving away from a national focus of monetary policies. And because countries could then target the same thing, exchange rate stability would naturally emerge. The issue of what basket to use would of course have to be faced, and this might be the most difficult challenge.

A global inflation target (using an aggregate CPI, GDP deflator, or personal consumption deflator) would be the most attractive on theoretical grounds but would face the greatest data problems. Instead of global inflation, G20 inflation would probably be a sufficiently good approximation, and this index could then provide a centerpiece for G20 coordination. Nevertheless, price indices would have to be harmonized (as in the European Union) for a G20 price index to be a reliable guide to inflation. A narrower index based on a basket of commodities traded on organized exchanges would provide a more straightforward and transparent anchor for policy. Moreover, targeting a basket of widely traded commodities could be implemented by buying and selling those commodities directly or by trading derivative instruments. Thus, a monetary policy commitment could, in principle, be achieved with a fair degree of accuracy in this case. However, the exclusion of manufactures and services might well cause problems if their prices relative to commodities changed in a major way (as has been the case in the past). Targeting a basket of commodities would be a vast improvement over a single-commodity anchor, such as gold, but nevertheless, the aggregate supply of commodities would come into play.

This is actually an old idea6, which was advanced by Keynes in his Treatise on Money and repeated by Richard Cooper at a Bologna-Claremont Monetary Conference (Mundell et al., 2005, pp. 138–39). Keynes proposed to have countries target a wholesale price index, which as Cooper points out, would have the advantage of including mainly tradable goods whose prices were readily available. Such an index could be stabilized while allowing other prices (in particular, nontraded goods and services) to rise, lessening the risk of overall deflation. Thus, targeting a stable level of wholesale prices could turn out to give an overall rate of inflation roughly equal to 2%. If so, the transition from current inflation targeting regimes to targeting wholesale prices would be eased. An objection to such a regime, however, is that it would target the most flexible prices, not the most sticky, and the latter is the basis for targeting “core inflation” by those countries that have an explicit inflation target. To work well, then, this regime would have to bring about greater flexibility of other prices and wages. This might be the price to be paid for enhanced exchange rate stability—or perhaps a collateral benefit of it.

5.6 Concluding Comments

For the first time in decades, the world's international monetary relations are subject to serious scrutiny. The relative decline of the United States and associated concerns about the dollar's value, the creation of the euro, and the rise of emerging market economies all suggest a move away from a system that is centered on the dollar. However, what form an alternative system might take is highly uncertain. One possibility is that a new monetary system with more constraining rules of the game could be put in place after international negotiation and agreement. Such a system would be unlikely to involve fixed exchange rates but could involve greater constraints on exchange rate policies, balance of payments positions, or macroeconomic policies. But past history suggests that reaching agreement on far-reaching international monetary reform is very hard to achieve and difficult to sustain. Moreover, there is considerable inertia in monetary relations. Instead, regime changes, if at all they occur, are often taken unilaterally, under the pressure of market forces.

These considerations lead some to conclude that the dollar's role at the center of the international monetary system is not really threatened and that the current “nonsystem” will continue in place: countries choose their macroeconomic policies and exchange rate regimes in a way that they believe is most conducive to achieving their domestic objectives. Policy coordination, if it occurs at all, is episodic and is a response to situations of generalized crisis.

However, there may be a middle ground in which policy coordination is institutionalized and strengthened through the operation of market forces, provided agreement can be reached on a common target for monetary policies. As discussed above, none of the traditional variables—whether exchange rates, balance of payments positions, or the overall stance of macroeconomic policies—seems to hold out much hope as a basis for rules-based coordination. It is suggested above that targeting a common price index instead might provide incentives for coordination and de facto exchange rate stability. If this were so, exchange rate regimes could evolve in a direction that provided some of the benefits of the Bretton Woods system without the associated currency and balance of payments crises.

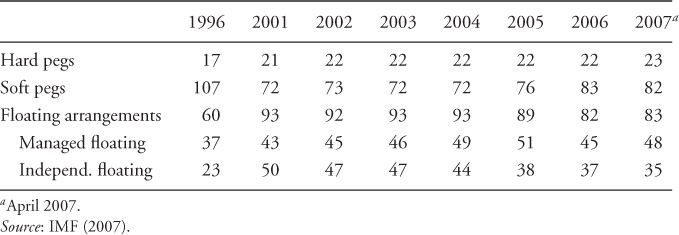

5.7 Appendix A: A Formal Test of Hollowing Out

The hypothesis of hollowing out needs to be supported by more than assertion or casual empiricism. In Masson (2001), the hypothesis is formally tested in the context of a Markov-chain model of the transitions between exchange rate regimes. In this model, the probability of moving between the three regimes—fixed, intermediate, and flexible—is assumed to be constant (including the probability of remaining in the current regime). Then, the hollowing out hypothesis can be equated with a test for whether the two polar regimes constitute a closed set—there can be transitions toward them from intermediate regimes and transitions between fixed and flexible, but none toward the intermediate regimes. This hypothesis can be tested on the estimated transition matrix. If true, the hypothesis implies that the long-run distribution of exchange rate regimes, obtained by iterating the Markov chain to infinity, would involve fixed and flexible regimes and zero occurrence of intermediate regimes.

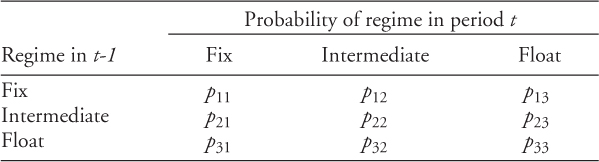

Writing this formally, let the transition probabilities be a matrix P = {pij}, with the sum across each row equal to unity. Thus, in the general case, the matrix has the following form:

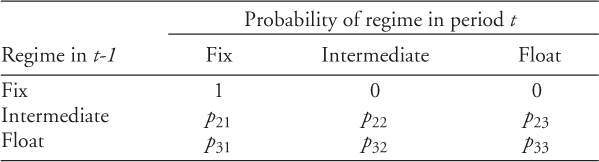

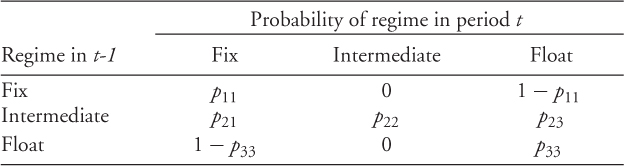

Hollowing out will occur if and only if one or both of the fixed and floating regimes constitute an absorbing state, or if they together constitute a closed set. In either case, there will be transitions away from the intermediate regimes, but no transitions toward them, so the distribution of regimes will in the long run not include any intermediate regimes.

If the fixed rate regime is an absorbing state, then the transition matrix takes the following form (and similarly if float is an absorbing state):

If the two polar regimes constitute a closed set, then

The long-run distribution of regimes can be found by iterating the transition matrix. If the initial distribution of regimes is given by π0, then the long run (or invariant) distribution will be given by  . It can be verified that in the two cases above, the invariant distribution contains no regimes in the intermediate category.

. It can be verified that in the two cases above, the invariant distribution contains no regimes in the intermediate category.

Testing the hypothesis of hollowing out involves estimating an unrestricted transition matrix and a transition matrix corresponding to an absorbing state or closed set, and doing a likelihood ratio test for equality between them. A difficult issue is the classification of exchange rate regimes into the three categories. The first difficulty is that countries officially report to the IMF regimes that do not correspond to actual behavior. Thus there have been several attempts to identify the actual regime. Second is the issue of dividing lines between fixed, intermediate, and floating. In defining regimes, Masson (2001) reports two classifications and defines fixes and floats relatively narrowly, in order to guard against biasing the test of hollowing out toward rejection (since a somewhat broader definition would produce more transitions away from the poles). Transition matrices are estimated over several time periods, but only estimates for the most recent time period, with the Ghosh et al. (1997) classification, are reported here. These estimates provide the most support for the hollowing out hypothesis.

| Estimated transition matrix, 1990–1997 |

| 0.9909 |

0.0000 |

0.0091 |

| 0.0055 |

0.9234 |

0.0711 |

| 0.0066 |

0.1093 |

0.8841 |

Test for a closed set of fixes and floats: reject at p < 0.0001.

Test of fix as absorbing state: reject at p = 0.137.

Test of flex as absorbing state: reject at p < 0.0001.

There were no transitions from fix (limited to currency boards and announced pegs with no changes in parities) to intermediate regimes in the sample, explaining why fix as an absorbing state can only be rejected at the 13.7% level7. Despite this, the implied invariant distribution gives a significant weight to intermediate regimes, one that is greater than the proportion either of fixes or floats in 1997:

1Starting with Sweden in 1924 and Britain in 1925. France, Belgium and Germany went back on the gold standard later, at currency values that were depreciated relative to the prewar gold content.

2Williamson, (1976).

3Such as Austria and the Netherlands within the context of the EMS, up until EMU and the replacement of their currencies by the euro.

4http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/10222010geithnerletter.pdf.

5Although the communist countries did not subscribe to it.

6I discovered this by chance, after having reinvented the wheel.

7The next decade was to see a notable transition away from a currency board in Argentina.

References

Alogoskoufis G, Portes R. The euro, the dollar, and the international monetary system. In: Masson PR, Krueger TH, Turtelboom BG, editors. EMU and the international monetary system. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 1997.

Bayoumi T, Eichengreen B. Economic performance under alternative exchange rate regimes: some historical evidence. In: Kenen PB, Papadia F, Saccomanni F, editors. The international monetary system. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994.

Carrère C. Revisiting the effects of regional trading agreements on trade flows with proper specification of the gravity model. Eur Econ Rev 2006;50(2):223–247.

Cassell G. The downfall of the gold standard. London: Oxford at the Clarendon Press; 1936.

Chinn M, Frankel J. Why the euro will rival the dollar. Int Finance 2008;11(1):49–73.

Chown JF. A history of money from AD 800. London, New York: Routledge; 1994.

Cohen BJ. The geography of money. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press; 1998.

——. Life at the top: international currencies in the twenty-first century, Essays in International Finance 221. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University; 2000.

Cooper RN. The future of the dollar. Foreign Policy 1973;11:4.

Côté A. Exchange rate volatility and trade, Working Paper No. 94-5; Bank of Canada, Ottawa; 1994.

Dailami M, Masson PR. Toward a more managed international monetary system? Int J 2010;65(2):393–409.

de Cecco M. Money and empire: the international gold standard, 1890–1914. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1974.

Dobson W, Masson PR. Will the renminbi become a world currency? China Econ Rev 2009;20(1):124–135.

Eagleton C, Williams J. Money: a history. 2nd ed. London: British Museum Press; 2007.

ECB. The international role of the Euro. Frankfurt: European Central Bank; 2010.

Eichengreen B. Golden fetters: the gold standard and the great depression, 1919–1939. New York, London: Oxford University Press; 1992.

Eichengreen B. International monetary arrangements for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): Brookings; 1994.

Flood RD, Rose AK. Understanding exchange rate volatility without the contrivance of macroeconomics. Econ J 1999;109:660–672.

Frankel JA. No single currency regime is right for all countries or at all times Essays in International Finance 213. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University; 1999.

Frankel JA. How can commodity exporters make fiscal and monetary policy less procyclical? HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP11-015. Cambridge (MA): Harvard Kennedy School; 2011.

Frankel JA, Rose AK. Estimating the effect of currency unions on trade and output, NBER Working Paper 7857. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2000.

Frenkel JA, Goldstein M, Masson PR. The Rationale for, and effects of, international economic policy coordination. In: Branson WH, Frenkel JA, Goldstein M, editors. International policy coordination and exchange rate fluctuations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research; 1990.

Funabashi Y. Managing the dollar: from the plaza to the louvre. Washington (DC): Institute for International Economics; 1988.

Ghosh A, Gulde A-M, Ostry J, Wolf H. Does the nominal exchange rate matter? NBER Working Paper 5874. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 1997.

Goldstein M. Managed floating plus. Policy analyses in international economics 66. Washington (DC): Peterson Institute for International Economics; 2002.

Helleiner E. Enduring top currency, fragile negotiated currency: politics and the dollar's international role. In: Helleiner E, Kirshner J, editors. The future of the dollar. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press; 2009.

IMF. Review of exchange arrangements, restrictions, and controls. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2007.

Keynes JM. The Economic Consequences of the Peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1920.

Kindleberger C. The world in depression, 1929–1939. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1973.

Masson PR. Exchange rate regime transitions. J Dev Econ 2001;64:571–586.

Masson PR, Ruge-Murcia F. Explaining the transitions between exchange rate regimes. Scand J Econ 2005;107(2):261–278.

Mundell R, Zak P, Shaeffer D, editors. International monetarypolicy after the Euro. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 2005.

Mussa MM. Nominal exchange rate regimes and the behaviour of the real exchange rate, Carnegie-Rochester Series on Public Policy; Amsterdam: North-Holland 1986. pp. 117–213.

Nurkse R. International currency experience. Princeton (NJ): League of Nations; 1944.

Obstfeld M, Rogoff K. The mirage of fixed exchange rates. J Econ Perspect 1995;9(4):73–96.

Persaud A. Is the Chinese growth miracle built to last? Manuscript; 2007 July.

Posen A. Why the euro will not rival the dollar. Int Finance 2008;11(1):75–100.

Rose AK. One money, one market: the effect of common currencies on trade. Econ Policy 2000;15(30):9–45.

Rose AK. A stable international monetary system emerges: Inflation targeting is Bretton Woods, reversed, NBER Working Paper 12711. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006.

Solomon R. The international monetary system, 1945–1981. New York: Harper and Row; 1982.

Triffin R. Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960.

Williamson J. The benefits and costs of an international monetary nonsystem. In: Bernstein EM, et al. editors. Reflections on Jamaica, Essays in International Finance 115. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University; 1976. pp. 54–59.

Williamson J. Exchange rate management. Econ J 1993;103:188–197.

Yeager LB. From gold to the ecu: the international monetary system in retrospect. Independent Rev 1996;1:75–99.

té, 1994). More recently, interest in this issue has been revived by striking results found by Andrew Rose and others (Frankel and Rose, 2000; Rose, 2000) that trade within currency unions is much greater than the standard gravity model would suggest. Some of this effect seems to come from lower exchange rate volatility, although some is specific to currency unions themselves (Carrère, 2006).

té, 1994). More recently, interest in this issue has been revived by striking results found by Andrew Rose and others (Frankel and Rose, 2000; Rose, 2000) that trade within currency unions is much greater than the standard gravity model would suggest. Some of this effect seems to come from lower exchange rate volatility, although some is specific to currency unions themselves (Carrère, 2006).

. It can be verified that in the two cases above, the invariant distribution contains no regimes in the intermediate category.

. It can be verified that in the two cases above, the invariant distribution contains no regimes in the intermediate category.