Within the Ardennes Offensive operations, Fritz Ludwig Carl Krämer is a strange figure. Krämer was a fully-fledged regular German staff officer, having graduated from the Berlin War Academy in 1934 and served on the staff of the 13th Panzer Division until 1942 in Russia. Krämer was brought into the SS Sixth Panzer Army to provide an experienced staff officer for operational matters relative to that organization. General Dietrich, the Army commander, had previously commanded the I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, but with his promotion it was necessary to bring someone in to fill his shoes. Krämer was the man. He had already been working effectively with I SS Panzer Corps on troublesome logistical matters in Normandy, although other Waffen SS officers deeply resented this encroachment. There was a deep rivalry between the regular Army and the Waffen SS, and Krämer was not originally an SS officer. Regardless of this, Krämer was assigned as Chief of Staff for the Army on Hitler’s personal orders on 27 October, having received good reports regarding his efficacy in Normandy. Krämer took over his new post on 16 November, just one month before the beginning of the attack. According to his own description, he immediately made an extensive study of the terrain and composed the battlegroups and their suggested march routes.

Prior to the attack, I made an extensive study of the road net in our zone, because 1 knew it would be one of our most difficult problems. As a result of this map study and my personal knowledge of the terrain, I selected the five routes you have on the map … These roads were to be directional only. If division commanders wanted to take others, they were at liberty to do so …1

The attack plan for Sixth Panzer Army was developed by Krämer in some detail. Although the Fifth Panzer Army’s von Manteuffel later accused the Sixth of attacking on too narrow a front, Krämer insisted that this was dictated by the terrain, the lack of roads for full deployment and the need for a rapid breakthrough. He anticipated an echeloned assault where mobile units were to attack at many points in columns, hoping to break out in several places and speed forward in road formation:

The principle was to hold the reins loose and let the armies race. The main point was to reach the Meuse regardless of the flanks. This was the same principle we used in the French campaign of 1940. My division in Russia used the same principle, and we advanced beyond Stalingrad. I never worry about my flanks … I believe, as Clausewitz, ‘The point must form the fist.’ Our general zone was Monschau–Losheim. The initial attack was to be made by two infantry corps. The LXVII Infantry Corps, with the 246th and 326th VG Divisions, was to attack in the vicinity of Monschau, move northwest and block the roads from Eupen to Monschau, and block the north against any enemy thrust in that direction. The I SS Pz Corps was to attack with elements of the 277 VG, 3 FS and 12 VG Divisions from both sides of Udenbreth and cut the three roads from Verviers to Malmédy. After the tanks had passed through [the lines] 12 VG Division was to swing north to the vicinity of Verviers … By noon, when we calculated the roads from the north would be blocked, the tanks were to move out, and the entire [infantry] line was to swing northwest so that the blocking line would run Eupen-Herve-Liège. The panzers were to attack in the direction of Liège and Huy to secure crossings of the river. We calculated that by noon of the 17th of December, we could reach the Hohes Venn mountains, which run northwest from Monschau to Stavelot. By 19 December, the panzer spearheads were to reach the Meuse …

The main worry for Krämer before the attack was the lack of recent reconnaissance of the enemy front. To protect the secret of ‘Wacht Am Rhein’, patrol activity had been sharply curtailed since early December. This left him believing that only a single infantry division opposed them between Monschau and Losheim, with another in reserve. ‘Our infantry did not progress as I had anticipated, due to several factors, including the rain and fog, a destroyed bridge just north of Losheim, and your very strong defensive sector in the Elsenborn–Butgenbach area.’

When he later learned that the veteran U.S. 2nd Infantry Division was attacking through the 99th Division, he acknowledged that this had severely thrown off their plans. But if Sixth Panzer Army was considerably derided among staff officers for its lack of experience, this view was certainly not held by Krämer. Said his interviewers: ‘He obviously has a comprehensive understanding of this operation, and his account should be considered very reliable.’ Jochen Peiper, the controversial commander of the German panzer spearhead, admitted that Dietrich had limitations as a commander. However, he said Dietrich performed satisfactorily if he had a good chief of staff, which Peiper certainly believed true of Krämer.2 The Historical Section officers who interviewed Krämer were also impressed:

I believe that far and away the most important interview which Merraim had was with General Fritz Krämer. This tight-lipped, straight thinking, regular Army officer, who was sent off to pound some sense into Sepp Dietrich’s SS head as the latter’s Chief of Staff, immediately impressed Merraim with his deep powers of analysis and grasp of tactical and strategic principles.3

Against this plaudatory evaluation, however, must stand a number of important failings in Krämer’s command. Firstly, he should have known that the chosen panzer Rollbahnen for his Army were woefully inadequate for the allotted motorized troops – Rollbahn A was not even paved for the first ten kilometres. Several of the others were similarly inadequate: Jochen Peiper, in charge of the prime armored spearhead of the 1st SS Panzer Division, said after the war that the narrow and circuitous Rollbahn D ‘was suitable not for tanks but for bicycles.’ And yet Krämer did nothing to get these routes changed. Secondly, Krämer did nothing to attempt to alter several key tactical issues in the assault which he must have known were in error. He should at least have attempted to cancel the preparatory artillery bombardments, as von Manteuffel in the Fifth Panzer Army had done, and to change the initial assault from the poorly-trained infantry divisions to the more experienced panzer troops. The thirty-minute artillery bombardment did little more than consume irreplaceable ammunition and alert the American forces in the area that an attack was in the offing. And leading the attack with the parachute units and poorly-trained Volksgrenadiers wasted valuable time, during which the experienced panzer troops may have been able to effect a rapid breakthrough and race across Belgium to the Meuse. But Krämer never asked for either of these concessions which von Manteuffel used to his advantage.

Although Dietrich would later shoulder the blame for each of these oversights, there is no evidence that Krämer attempted to get him to change Hitler’s mind on either of these flaws (the reality is that Dietrich had wanted to make the breakthrough in the Losheim Gap with the tanks of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler leading the assault – a plan that was overruled by OKW on 11 December). In hindsight, this has to be seen as the greatest of oversights – possibly one that, having been addressed, might have taken the Sixth Panzer Army to the Meuse River by the end of the second day of the attack.

Despite ingratiating himself to interrogators, the problems for Krämer after the war stemmed from his very involvement with the Sixth Panzer Army. As most know, during the Ardennes Operation the ‘Malmédy Massacre’ incident took place on Krämer’s watch, and the sentiment in the American public was that SS heads should roll. During the Malmédy Trial at Dachau, the U.S. prosecution went to great lengths to implicate Dietrich and Krämer, saying that both had been involved with issuing orders that no prisoners were to be taken – an order for which no physical evidence was ever produced, and which most Germans involved denounced as untrue. Indeed, Krämer told of having first learned of the ‘massacre’ from Radio Calais on the 20th of December – a fact that seems true. But regardless of guilt, Krämer was convicted in the trial along with Dietrich and the others. He wept openly when his sentence of ten years imprisonment was pronounced; he would not be paroled until 1951.

Danny S. Parker

The Staff of the Sixth Panzer Army was formed in October 1944 at Bad Salzuflan, Westphalia. The personnel consisted of about 2/3 Officers and enlisted men of the Regular Army, and about 1/3 Officers and enlisted men of the Waffen SS. Two-thirds of the strength of the Signal Communications Regiment consisted of members of the Luftwaffe.

This Army was often called the Sixth SS Panzer Army. Its correct designation however, is the Sixth Panzer Army, according to a written directive of the German High Command issued in the beginning of December, 1944.

Commanding General: General of the Waffen SS Dietrich.

Chief of Staff: Lt Gen Gause. As of 18 Nov 1944, Major General of the Waffen SS Krämer.

I SS Panzer Corps with the 1 and 12 SS Panzer Divisions.

II SS Panzer Corps with the 2 and 9 SS Panzer Divisions, and the Panzer

Lehr Division of the Regular Army

I SS Panzer Corps: Lt Gen of the Waffen SS Fries.

Chief of Staff: SS Lt Colonel Lehmann.

1st SS Panzer Div: SS Brig Gen Mohnke.

12th SS Panzer Div: Maj Gen of the Waffen SS Krämer: as of 15 Nov 44, SS Brig Gen Kraas.*

II SS Panzer Corps: General of the Waffen SS Bittrich.

Chief of Staff: SS Lt Colonel Keller.

2nd SS Panzer Div: Major Gen of the Waffen SS Lammerding.

9th SS Panzer Div: SS Brig Gen Stadler.

Panzer Lehr Division: Lt Gen Bayerlein.

These divisions, which were badly defeated during the Invasion and the retreat towards the Westwall, were still employed at the Front in the beginning of October 1944. They were deployed as follows:

1st SS Panzer Division: Special units of which were employed to the northwest of Prüm and Daleiden.

2nd SS Panzer Division, majority of which were employed on both sides of Prüm.

9th SS Panzer Division: at Arnhem.

12th SS Panzer Division: part of this division northwest of Prüm.

Panzer Lehr Division: part of this division at Neuerburg.

Remnants of the divisions which were broken to pieces, re-assembled in the sector around Heilbronn; towards the end of October they were shifted to the sector around Minden.

The Commanding Staffs were not immediately relieved from the Front; that of the 1st SS Panzer Division arrived on the 22 Oct 44, and of the 2nd SS Panzer Division in the middle of November. The extrication of all the Divisions with all of their component units was completed towards the end of October. At this time the majority of these units were assembled as follows:

1st SS Panzer Division in the sector SW of Minden.

12th SS Panzer Division in the sector North of Minden.

2nd SS Panzer Division in the sector of Arnsberg.

9th SS Panzer Division in the sector of Hamm, Westphalia.

The Panzer Lehr Division was not attached at this time.

The Divisions were commanded to reorganize, to retrain and to be ready to resist enemy air landings in their billeting sectors. The retraining, instruction and reorganization of the forces suffered serious delay through interruptions and rerouting of the supply and equipment trains from the interior of Germany because of a succession of enemy air attacks.

The divisions endeavoured to reorganize their units as soon as possible and strove to accomplish this with the greatest speed. Special importance was given to instruction in night fighting and combined operations of the various units. Officers and enlisted men who knew no battle assaults since the Invasion, again had to study the characteristic employment of Panzer Divisions as an assault arm. The training of drivers, who, in the past, had been used as infantrymen and had suffered serious casualties, was handicapped by a serious shortage of motor fuels. This lack of training was to prove costly to the Ardennes Offensive because of the bad network of roads. However, the attitude and morale of the troops was very good.

On 9 Nov 1944, the Divisions received the order for movement by rail. The destination and the sector were unknown. The requests of the Divisional Commanders to wait 14 days to three weeks for shipping, in order to complete the retraining, was not granted by the Army. The train transportation – 60 trains to each division – operated almost without breakdown and reached their destination despite air attacks. The movement was completed on the 20 Nov 44; fresh troops and equipment – tanks, motor vehicles, etc – continued to arrive until the beginning of December, at which time the organization of the Panzer Divisions was completed.

Towards the end of November, the units which were reserves of the OKW – High Command of the Armed Forces – were located as follows:

Army Staff and Army Troops in Quadrath, west of Köln, and in Bruehl.

I SS Panzer Corps in Frechen, west of Köln.

1st SS Panzer Division southwest of Köln.

12th SS Panzer Division northwest of Köln.

II SS Panzer Corps, west of Bonn.

2nd SS Panzer Division south of München-Gladbach.

9th SS Panzer Division in the region of Euskirchen.

Army Supply Troops west of the Rhine between Köln and Bonn.

The Corps received the order to continue the training – particularly night training – and to prepare themselves to repulse Allied air landings. Mobile reserve units were to be held in readiness. The troops were of the opinion that they were to act as reinforcements in the battle of Aachen. That was also the general opinion of the population. Vehicles were camouflaged against air observation, and motor movements were only executed at night. All members of the Army and even individuals were forbidden to cross to the west of the highway Neuss–Grevenbroich–Liblar–Euskirchen.

The dominating theme of the Officer map exercises and sand table training was: ‘Attacks against the flanks and the rear of a motorized enemy who had made a penetration in depth to the main defensive area and even into the interior of the country.’ The troops did not know that they were assembled for a large-scale offensive.

1. Tactical: The advance preparations for the operations were carried on in the greatest secrecy. On 16 Nov 1944, on order of the Führer, General Krämer became Chief of Staff of the 6 Pz Army and received instructions about the intended Ardennes Offensive by his predecessor Lt Gen Gause and the Commander in Chief of the Army. Other officers were not advised, written orders not being left with the Army.

The Plan of Operations in general was:

Attack with two Panzer Armies on both sides of the Schnee-Eifel across the Maas (Meuse).

At the same time:

a. Screening of flanks with Infantry Divisions.

b. Exploiting of a bad weather period in order to eliminate air offensives.

c. Heaviest artillery and support through air cover.

Details over the assignment of other forces were still unknown. The moment of the Operation was given as the beginning of December. Through a discussion on November 18th with the Chief of Army Group B, General of the Infantry Krebs, it was again expressed that with the precise moment of this attack (and its secrecy) hung the success or failure of this operation. The introduction of other officers to this plan could only be done through the approval of the Army Group. There were two proven possibilities of this operation and they were:

(1) Frontal attack on both sides of Aachen and attack with the right wing along the Maas at Maastricht, in order to defeat the forces (especially British) concentrated near Aachen.

(2) Thrust across the Maas from the sector of the Schnee-Eifel to rip apart the front of the Allies and thrust to Antwerp and Brussels, to cut off the supply routes.

The Führer had ordered the second plan. As they intended with the 6 Panzer Army on the right and the 5 Panzer Army on the left under the advantage of a bad weather period, to thrust on both sides of the Schnee-Eifel over the Maas between Lüttich (bypassing this) and Namur. Bad roads had to be figured on. The moment of the commencement of the operations was about 10 December. The right flank of the 6 Panzer Army was to be backed up by 15 Army, supplying an infantry corps which was to be attached to 6 Panzer Army. The left flank of 5 Panzer Army would be protected by an advance of the 7 Army in direction southwest. It was further intended to relieve the right flank of 6 Panzer Army by an attack of 15 Army with two Panzer divisions and the corresponding infantry divisions with the right wing along the Maas toward Maastricht, and to contain the enemy forces that would eventually be committed for a thrust into the deep flank of the Army.

The Army informed the Army group that:

a. The training of the division not being accomplished, the beginning of the operations should be postponed.

b. Two Panzer Divisions should be committed side by side of the Hohes Venn and Schnee-Eifel, in order to:

(1) form a strong breakthrough wedge,

(2) exploit the favorable terrain southwest of Prüm, and to bypass the terrain of the Hohes Venn, difficult for the tanks.

The difficulty of the terrain was well known because of the withdrawal battles toward the Westwall. The Army knew that a strong demand would have to be made on the efficiency of the troops, and in particular on the drivers. The training and the reorganization of the Army was watched over during the days that followed and the Officer Corps received further training in map studies. To mask their true nature, the training courses were based on the idea that motorized enemy forces that had broken through were to be attacked in the flank. That was obvious to all the participants, as the Allied effort was being shown in their thrusts through to the Rhine. Army Group B had map exercises similar to that of the Army.

Terrain reconnaissance west of the line Grevenbroich–Euskirchen was forbidden. However, the Army received information about the enemy by the Ic of the Army Group. Close contact was kept between the group of Manteuffel (5 Panzer Army) committed as first advancing group, and the 7 Army. We knew that comparatively weak enemy forces were situated in the sector Krewinkel–Gemünd. It was supposed that three divisions were assembled in the area of Elsenborn for an attack on the dam of the Urft-valley. Between the front line and the Maas, the enemy forces seemed relatively weak. An armored division was supposed to be situated north of Spa, which would be the first combined group to make an attack against the right flank of the Army. In front of the left wing of our 7 Army strong radio activity could be observed, therefore we concluded that strong enemy forces were concentrated there.

The 6 Panzer Army never received any details on this subject. All in all, we had to expect, that only on the 3rd day of our breakthrough attack (if launched immediately), countermeasures of combined enemy units would be started, and that the combined divisions would only be committed on the other side of the Maas against the Army. The enemy main resistance line did not consist of a continuous line, but of different strongpoints (especially near roads and forest trails), and had a depth of about 4–5 km. Tanks and tank emplacements, that were employed as reserves for counterattacks, backed up the strongpoint. A decrease of the combat strength, due to the cold weather and the insufficient winter equipment, was expected. Close contact was kept between the Group of Manteuffel and the 7 Army. Even for those, who were not informed about the offensive, this seemed to be necessary, because the Army (for those who did not know) was assembled there as reserve for the fighting near Aachen.

About 20 November 1944, a written order went to the Army for the intended offensive. They dared not work on it other than the C-I-C, the Chief of Staff, and the first General staff officer – the latter also all had to write the plan themselves, and nothing concerning the plans was to be made known to the troops. The message was as follows:

The 6 Panzer Army, with the attached infantry divisions, on X-day, after heavy artillery preparation, will break through the enemy defensive front in the sector of Monschau–Krewinkel, then – regardless of their flanks – push with their armored units across the Maas, south of Lüttich (Liège), then – screening their right flank on the Albert-Canal – push toward Antwerp. Specially organized advance detachments under the command of particularly energetic officers, were to take the bridges across the Maas, south of Lüttich, undamaged. The LXVII Army Corps is to be committed in the general line Monschau–Verviers–Lüttich for the formation of a solid defensive front. After having crossed the Maas, the Corps will be reattached to the 15 Army. Boundary line to 5 Panzer Army: Prüm–St Vith–Huy. 10 December was again anticipated as X-day.

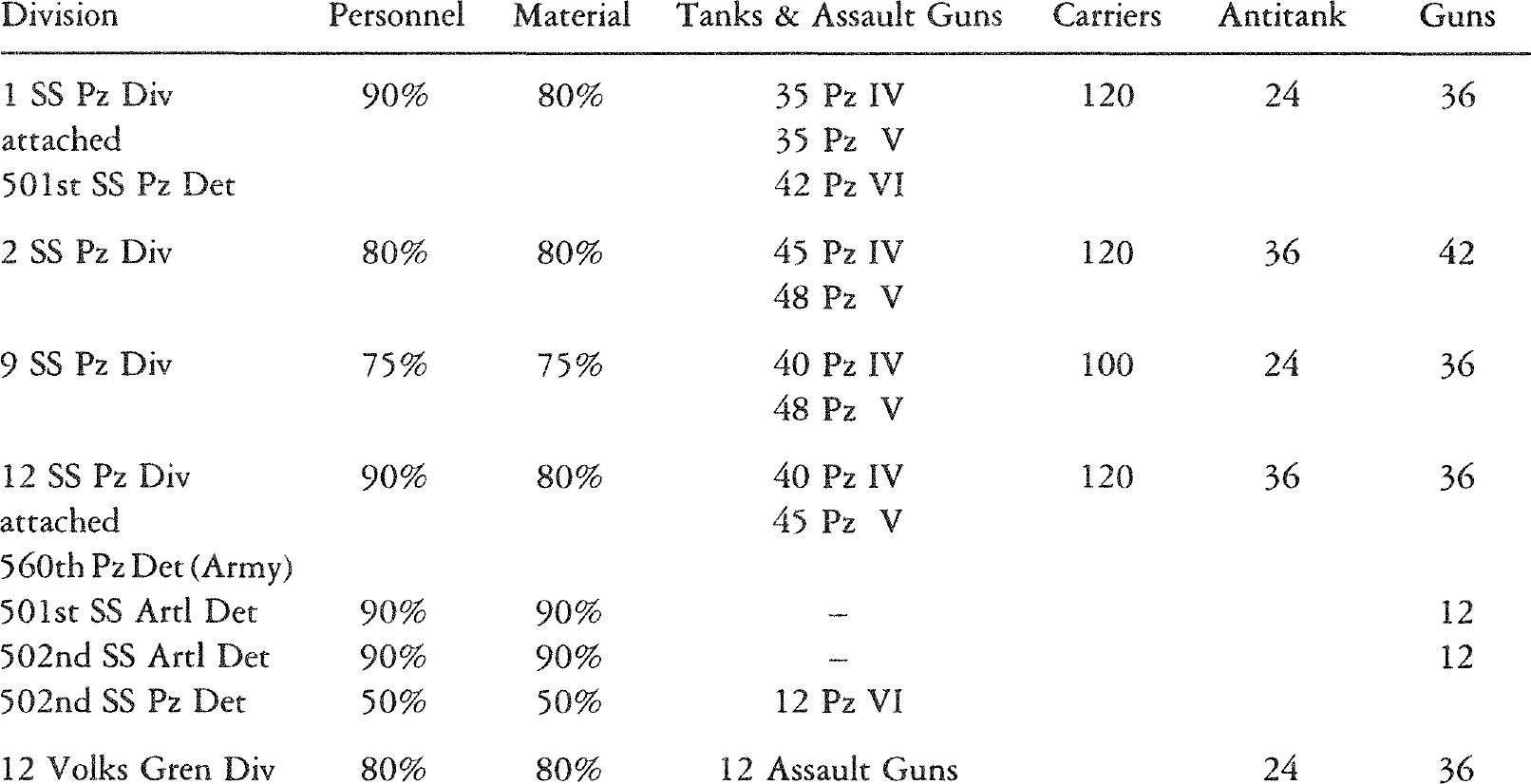

With the beginning of the strategic concentration of troops for action, the Army was organized as follows: (See organization of the 6 Panzer Army on 15 December 1944.)

The orders of the Army, that were worked out by the Chief of Staff and the la officer were very detailed and complete. The Army Group received a copy of the orders. It was pointed out that it would be better to postpone the start of the operation, in order to accomplish the re-equipment of the troops. The train transports with the material arrived only with great interruptions, because of the air raids. Since various arms and spare-parts did not always come from the same ordnance service, it sometimes happened, that parts were missing and had to be requested again. On 1 December, the artillery Commander of the Army, Lt Gen of the Waffen SS Staudinger and an artillery expert, Lt Gen Kruse (sent from the German High Command) received instructions. During a map exercise on 2 December, at Bruehl (south of Köln), the Commanding Generals and their Chiefs, and the Commanders of the Panzer Divisions were instructed. All steps had to be as before, with the view in mind of the defensive battles that were to be carried through. In this map exercise, in the presence of the C-I-C and under the guidance of the substituted CO, General of the Waffen SS Bittrich, the Commanding Generals, their Chiefs and the Commanders of the Panzer Division took part in the discussion of all the plans of the Army.

The army had to be entirely clear, on which places and on what time of the day the attack was to be started. The assigned Infantry divisions came in part from defensive combats and were not complete. Their reorganization followed a very short delay and their fighting qualities were not of the best. The best division was the 12 VGD that had an especially skilled Commander and had fought excellently in the Battle of Aachen. The 3 Para Div had no battle experience, and besides their Commander had very little understanding about infantry matters. The time of attack was scheduled for the early morning hours, because it was hoped, that the infantry would succeed in taking advantage of the early morning mist and succeed in breaking through the first positions. It was hoped that by midday they would win 5–8 km of ground. For a night attack, the troops were not sufficiently trained to take advantage of the most favorable time. The troops had lost themselves in the fields, the military security of the enemy was on the alert, and the Panzers in the gray of the morning had a foe held in readiness, standing opposite them.

About 200 searchlights were available of the III Flak Corps, that had worked together with the Army. Repeated attempts would be made to break through with searchlights. But it proved that the searchlights were not mobile enough and their maximum range was too limited to follow the troops.

Also important was the choice of the sector of the attack. There had to be favorable departure positions for the infantry and ones had to be especially sought out for the Panzers. The [Ardennes] country – extremely difficult for the combined attack of the Panzers – was above all especially unfavourable in the sector of the 6 Panzer Army. Open country for the operation of Panzers was first found after having passed the Hohes Venn. Until there the Panzers, in general, could not move off the road. The Army after careful consideration of the existing roads, and specific evaluation of the terrain, designated five roads, of these the four southern ones were designated as the so-called Panzer rolling roads. This was not an ideal situation, but the best selection had to be made. It was especially important for the Army to take the necessary measures, so that sufficient infantry strength could be brought up from the right side, in order to protect the right flank of the advance. The difficulty lay not only in regrouping these forces in time after the breakthrough, but to make sure that there would be sufficient room for the combat zone, and that supplies would not be cut off through a blocking of the roads by the Armored divisions. For the Army, this was not a pleasant solution, that they had to take over the protection of their flanks with infantry divisions.

By this order, they were bound on their right flank and as the proverb says: ‘horses and mules were tethered together.’ In no case were the Panzer Divisions to turn too early [to the north], because they were too weak for that task. Though all the available roads were to be exploited, it was the intention of the Army to reserve the northern tank track for a reinforced armored reconnaissance detachment. Afterwards, this road was to be reserved for infantry divisions. The request of the Army to give the task of the flank protection to the 15 Army was refused. Presuming that three enemy divisions (forces for an attack on the dam of the Urft and replacements) were situated in the area of Elsenborn, the Army decided on the commitment of three infantry divisions in that sector. However Army Group B altered that plan and committed only two divisions. It was also important to decide whether the Panzer Corps were to be distributed in depth or in line. The Army should have preferred disposition in line, which would have permitted the commitment of a greater number of tanks. However, the terrain was so difficult that the traffic would have been tied-up. Moreover the Army needed tank reserves for commitment, in case the situation of the right flank became critical or the infantry could not be brought up as rapidly as expected. Further, under this arrangement, the Army had the possibility to commit fresh forces, after the first wave of the attack was consumed. Therefore disposition in depth was ordered and approved by the Army Group.

The traffic control was of particular importance. Therefore a Military Police Regiment (300 men) was put at disposal of the Army in addition to the already existing MP forces (for each Panzer Corps and each Panzer Division one company of MP).

On or by 10 December all the Corps received the detailed orders of the Army. On 8 December the Army took over the command of the supply services of the sector, and on 10 December the staff shifted their Command Post to Münstereifel. On 11 December the Army took the tactical command of the sector Monschau–Schnee Eifel. With regard to the weather, the still uncompleted reorganization of all divisions, and disposition of the artillery, the beginning of the attack was first postponed to 13, then to 16 December.

On 12 and 13 December, a meeting of all the commanding Generals and division commanders took place at the Command Post of the OB West, where Hitler explained reasons and necessity of the Offensive and insisted upon the necessity of employing all the forces, in order to obtain the final success. The general lines of the detailed order of the Army were as follows:

6 Panzer Army, on X-day, after heavy artillery preparation breaks through the enemy front in the sector on both sides of Hollerath and pushes – regardless of their flanks – without stop, across the Maas toward Antwerp.

I SS Panzer Corps, on X-day, assembles at 0600 hours, breaks through the enemy positions into the sector of Monschau–Udenbreth and Losheim, then with 12 SS Panzer Division on the right and 1 SS Panzer Division on the left, pushes across the Maas into the sector of Lüttich–Huy. Then, according to the development of the situation, it is the task of the Corps, either to continue without interruption to Antwerp or to be ready for the protection of the right flank on the Albert-Canal.

By a rapid assault, carried out by specially organized advance detachments, under the command of particularly energetic officers, the bridges, situated in the Maas sector are to be captured undamaged.

The following units are attached: 277 Volks Grenadier Division, 12 Volks Grenadier Division, and 3 Para Division. The 3 Para Division and the 12 Volks Grenadier Division after accomplished breakthrough of the enemy main zone of resistance, will return under the command of the Army.

The II SS Panzer Corps will be situated close behind the I SS Panzer Corps, in order to follow them immediately. The II SS Panzer Corps has the mission either: to cooperate with the I SS Panzer Corps to push toward the Maas; or: immediately after having crossed the Maas – regardless of their flanks threatened by the enemy – to push toward Antwerp. Permanent contact with the I SS Panzer Corps has to be maintained. Motorized advance detachments are to follow the last fighting parts of the I SS Panzer Corps. Therefore the Corps is responsible that the approach routes behind the I SS Panzer Corps be free.

LXVII Army Corps, on X-day, with the 326 and 246 Volks Grenadier Divisions breaks through the enemy positions on both sides of Monschau – after having crossed the road Mützenich–Elsenborn turning north and west – and establishes a fixed defensive front approximately in the line Simmerath–Eupen–Limburg–Lüttich.

The 12 Volks Grenadier Division and the 3 Para Division are to be committed west of Limburg for the prolongation of the defensive front. Along the highways and the communication roads running from north to south, temporary holding positions are to be established toward north, backed up by tank groups in extended formation to the rear and the flanks. The elevated terrain around Elsenborn is to be secured.

A special order was given to the artillery, scheduling preparation, support of the attack, further activity and subordination of the artillery during the development of the combat. Besides the artillery belonging to the Army, 3 Volksartillery Corps, 2 Volkswerfer brigades and 3 detachments of heavy artillery were attached to the Army. The artillery of the Panzer Corps took part in the preparation.

The observation batteries of the I and II SS Panzer Corps were employed from 28 November for reconnaissance of the enemy artillery. This measure proved very useful, but almost provoked a catastrophe. Approximately on 1 December, a strong American reconnaissance detachment penetrated an observation post of the I SS Panzer Corps. Two of this detachment were missing. Evidently they were killed, or did not give any information, when they were captured. Anyway, the Army never found out whether the Americans obtained information on the planned offensive.

At a meeting of the Commanders in Chief and the Army Chiefs in late November, Obersturmbannführer Skorzeny was present. That day the Army was informed that a combat team under the code-name ‘Operation Greif’ equipped with American uniforms and vehicles should take part in the offensive, advancing in front of the armored spearheads, taking the bridges undamaged and re-routing American march columns. Assembly of this combat team (code-name ‘150 Panzer Brigade’) was conducted in Grafenwöhr (Bavaria).

They were brought up by train to Münster–Eifel. The brigade could not accomplish their preparations, and arrived with only 10 Sherman tanks ready to be committed and 80 American or British vehicles. A special order was issued for the commitment of this brigade. A copy of the offensive fell into the hands of the enemy on the third day. However this did not affect the commitment of the brigade, because it had no more been possible to send parts of this brigade ahead of the armored points.

Beginning 1 December, no more reconnaissance activity of the advanced units was allowed. This should prevent our men, if they were made prisoners, from betraying anything concerning the approach of the artillery that could not be kept hidden from the advanced units. This security measure had to be taken, in spite of the insufficient information we could obtain regarding the enemy at that time.

In order to feign the concentration of stronger forces, on order of Army Group B, the assembly of 25th Army (which in reality did not exist) took part in the area München-Gladbach–Köln– Dusseldorf. This Army was composed of smaller operations staffs equipped with radio deception. Whether this deception was very successful, the Army never knew. The population believed that these billets were for a great number of forces.

On 10 December the Army was informed that also parachute troops would participate in the operation. A parachute detachment of about 250 men [sic; there were approximately 1,000 men in the operation] under the command of Lt Col von der Heydte would jump on the day of the offensive in front of the armored points, in order to:

a. either open the road for the tanks in the area Hohes Venn, or:

b. prevent the American advance between Eupen and Verviers, before a defensive front was established.

The Army requested the commitment of the parachute troops in the area of Monte Rigi (12 km southeast of Verviers), because this area seemed the most favorable for the operation. The team brought many dummies with them, in order to feign a bigger jump-operation.

Because the reinforcements (artillery etc.) and the supplies for the re-equipment did not arrive in time the beginning of the offensive had to be postponed to 14, and later to 16 December.

The code-word for the postponement was known only to the Chiefs of the Staffs of the Armies and Corps. On 11 December the Army took the command of the sector of Monschau–Ormont and shifted the Command Post to Münstereifel.

2. Supplies: As with the tactical preparations, all of the preparations for supply to be carried out from the viewpoint of the greatest secrecy. All participating organizations were not advised until the last hour of the goal of all of their preparations. They were led to believe that the supplying of all types of materials and supplies were needed for defensive battles.

The supply task was divided into two parts:

a. Transports for the retraining of troops. It had been explained to all participating commands that the Panzer Divisions had to be brought up to their former strength. Moreover in a defense battle, it was an everyday event to bring up new forces and new material to burned out divisions.

b. Transports for the Operation: On account of the serious air attacks on the interior of Germany, the OKW ordered that the mass of the supplies be stocked on the east bank of the Rhine. The preparation for the stocking of supplies on the west bank of the Rhine was taken over by the Armies and Corps situated there. About 11 December, there was a conference held in Münstereifel over the question of the supply during the Operations, in which the Quartermaster General Major Toppe took part. The Army took over from 10 December the forwarding of supplies for all the troops in their assigned sector pretending that the supply services of the 7 Army were not sufficient for the sector and that the Chief Quartermaster Division of the 6 Army had to take over part of the work.

Up to 12 December were prepared:

(1) Gasoline supplies providing for 300–400 km of travel, 60% of which were in the hands of the Army respectively of the attached Corps (would go about half as far in the Eifel terrain).

It was ordered that 1 consumption unit (vs = 100 km of fuel) be brought up daily. Assuming a normal bringing up of the supply, and reasonable economy of the participating divisions, it must be possible to secure the necessary daily gasoline without having to count upon captured supplies.

(2) Munitions: three issues:

(a) as expenditure for artillery fire

(b) for tactical use during the battle

(c) to be distributed in dumps, situated in the rear areas.

(d) Rations food supplies. Separate steps were not necessary since these were received in permanent ration depots.

The new supply troops of the Army were located along the west bank of the Rhine, the Chief Quartermaster in Bruehl. As far as necessary, the supply troops committed until now in the sector, were taken over by 7 Army. The commitment of new supply troops would follow immediately upon the beginning of operations. All preparations in this sector were carried through with the greatest care.

(3) Organization of the Army on 15 December 1944 (Encl. 1).

The strategic concentration was carried through under the camouflage (code name) of (‘ABWEHR’) ‘Defense’. Not until 14 December was the name disclosed and passed along to the Regimental Commanders. With this event arose the possibility of deserters or captured prisoners of war giving away the codename.

In order to preserve all the motor fuels, all troops and all types of materials needed for the operation were forwarded by train transport. In spite of enemy air superiority, and with but few exceptions, the loaded trains arrived at their destinations intact. As a result of the continuous air attacks, the troops were exceptionally well trained in camouflage. There were more trains operating for this operation than there were for the 1940 Western campaign. Even though troops often had to proceed by foot marches to their destination, the transports were brought up according to plan with only little delay.

All routes of the cross-country march, both motorized and foot, were only traveled by night. An especially difficult problem was the bringing into position and the installation of the reinforcement artillery. The fire-plan was known to the artillery commander and specific members of the Staff, under the code name ‘ABWEHR’ (‘Defense’). The movement forward was not to begin until 8 December and only by night. In the often impassable forest country, and in the dark, misty night hours these operations were not easy. It was often extremely difficult to find the right roads since the gun positions were not permitted to be marked. The guns could not be brought into a direct line until 10 December and altogether they lay 6 km behind the Front Line. As it was not always possible to avoid rattling noises and cursing during the quiet hours of the night, the guns were brought to the fire positions by horses and personnel trains. The wheeled vehicles rolled over straw-covered road. Fires were not permitted and no talking was allowed. When one stops to think of these operations at the present time, and that normally all of these movements were only accomplished with loud noises, cursing and abuse, then it must be said that the troops really accomplished a wonderful performance. Just as difficult as the bringing of the guns into position and installing them was the bringing up of the munitions. Also we dared not bring up the munitions to the present gun positions, but rather kept them on a separate line situated about 8 km from our advanced positions. The munitions had to be hand carried over the last stretch of road. This was indeed a very troublesome and laborious work, but the soldiers carried it out willingly. By 13 December, all of the heaviest artillery was in position and well-camouflaged.

From 14 December, the Infantry Divisions were brought up in night marches and assembled. The retraining of the Infantry Divisions was not as advanced as the Army had anticipated. Additional personnel and equipment was added to the Divisions on 15 December. The 3 Para Division on account of a hard battle in the sector of Jülich–Düren was committed there and their releasing took a longer time than expected, so that the Division, with only two regiments which were ready for battle could fall in on the morning of 16 December.4 On the whole, the assembling of troops for action on 15 December by midnight was accomplished according to plan. It would have been much better, if the troops had had two or three days more time in which to become acquainted with the country in which they found themselves and in which they were preparing to attack. However, such suggestions of the Army were refused by the Army Group, who had received very strict orders from the High Command.

The Panzer Divisions were gathered together in their assembly positions after two night marches which began on 12 December. The marches were carried out under cover of darkness, so that all of the motor vehicles, which had not arrived in their assembly areas by the early gray hours of the morning, had to remain where they were. For the orderly execution of these movements it was necessary to set up an extensive system of traffic control – MPs – to effect a repair and recovery service for the motor vehicles which had fallen behind in order to prevent them being seen by day.

The sheltering areas of the Panzer Corps were so selected by the army, so that their assembly area could only be reached without difficulty. The many wooded areas and forests in this sector greatly facilitated the work of assembling the troops, the munitions and the motor fuels. The morale of the troops was very good.

In the end, all preparations had been carried through so that the breakthrough at least to the Meuse had to be successful. The German High Command expected that the Maas would be reached within two days time.

The Army had to set up the following calculations:

One day to break through to the enemy positions.

One day to go over the Hohes Venn with the Panzer Divisions.

Two days to cross over the Maas – altogether four days.

The air force and the III Flak-Corps the Army was obliged to co-operate with, were closely instructed in the intentions of the Army; with the Army were some Liaison Officers for the Luftwaffe who were equipped with Signal communications.

16 December: At 0530 hours started the very strong artillery preparation on the whole front. Till 0600 hours the artillery fired on the enemy advance positions and continued harassing fire on enemy batteries, reconnoitered by the observation batteries.

The attack of the infantry that started at 0600 hours, was backed up by light and heavy batteries. As it was still too dark for the forward observation posts to see anything, the fire had to precede the infantry. Heavy batteries continued harassing fire on enemy batteries. The preliminary operation was carried out by special assault troops (infantry and engineers). The infantry advanced without difficulty at all points of the breakthrough. The enemy artillery started fire only after 0800 hours. From the sector of the 12 Volks Grenadier Division it was reported that an overpass was blown up near Losheimergraben, that could not be repaired by their forces. Engineers of the I SS Panzer Corps were sent out immediately, who repaired the bridge temporarily and built an emergency bridge for the tanks. At about 1300 hours, the infantry had made a general advance of 4 km into the enemy positions. Isolated assault troops reported retrograde movements of the American infantry corps. However the Army was of the opinion, that only the dug-in outpost positions were drawn back to the main resistance line, but not that the whole main resistance line was withdrawn. At road crossings and forest trails, where tanks were backing-up the American infantry, the resistance was tough and the attack made only slow progress. Tank emplacements had to be bypassed. The condition of the roads was bad, they were partly mined, and the terrain was very muddy, which made the commitment of the tanks off the road almost impossible. In order to exploit the initial success of artillery and infantry, the Army ordered the commitment of panzer divisions of the I SS Panzer Corps, with the instruction to commit first only armored infantry and engineers for the backing up of the infantry and to commit the tanks afterwards.

During the morning, the Army shifted their Command Post to Marmagen.

At about 1700 hours the situation was as follows: The LXVII Army Corps that had broken through approximately 2–3 km into the enemy positions, had great difficulties in overcoming the terrain. The Army had reckoned with these difficulties and ordered the Corps to continue the attack even during the night, and pointed out that enemy attacks from the area of Elsenborn southwest had to be smashed by all means. Two assault gun brigades were brought up to the Corps to assist.

The 12 Volks Grenadier Division, the attacking group of the I SS Panzer Corps, backed up by armored infantry of the 12 SS Panzer Division, had made good progress. The operations were not yet finished, the American resistance was particularly tough and the losses very high in the area of Losheimergraben. The attack group (3 Para Division) had met at the beginning stiff resistance, but a motorized group of the 1 SS Panzer Division was advancing on the road Honsfeld–Möderscheid. Details were still missing.

The I SS Panzer Corps received orders from the Army to continue the attack with the infantry during the night and to fall in the next morning as early as possible with the panzer divisions. In no case was the 12 SS Panzer Division to be engaged in fighting against the enemy, who eventually would attack from the north. An Army engineer battalion was made available for the repair of the bridge in the area Losheimergraben.

The II SS Panzer Corps was informed about the situation and instructed that, in case of a favorable progress of the attack of the I SS Panzer Division, a division of the II SS Panzer Corps would be committed behind the I SS Panzer Division.

During the night 16/17 December, the first part of the II SS Panzer Corps was advanced to the line Gemünd–Stadtkyll.

There were no attacks of the enemy air force on 16 December and the poor flying weather was favorable for the Army. The enemy artillery activity had been comparatively weak, although a stronger artillery group were reported in the area of Elsenborn.

Our artillery displaced to change their position; this was started already by mid-day.

17 December: A portion of the attacks had continued during the night. The LXVII Army Corps with 326 and 246 Volks Grenadier Divisions [sic] had opened the road Monschau–Mützenich, and a strong combat team was advancing past Höfen toward Kalterherberg.5 Monschau was to be bypassed. On orders of Field Marshal Model, this German town was not to be fired on by artillery, in order to spare the lattice-work houses.

In the morning, the Army ordered the Corps to open the road Kalterherberg–Elsenborn and to attack the forces situated around Elsenborn (artillery and reserves). Till the late evening hours, this was impossible, the road being effectively blocked by abatis and mines.

The 277 Volks Grenadier Division was to continue their attack on both sides of Udenbreth past Krinkelt–Wirtzfeld for a later assault on Sourbrodt, south of Elsenborn. The division was reinforced by its assault gun company [six StuG III] that had not been ready for the commitment on 16 December (because the last parts of this detachment could only be extricated during the night 15/16 December). It was to be expected that the division with their attack in the direction of Elsenborn would gain terrain and contain the enemy forces that were situated in this area. The division had particular difficulties with the terrain.

In the morning, a message of the I SS Panzer Corps reported that the combat team of the 1 SS Panzer Division had broken through at 0400 hours but no more detailed information was available.

The 12 Volks Grenadier Division, that presently was attacking Hünningen, was ordered now to cooperate with the 12 SS Panzer Division and to open the road across Weismes in the direction of Malmédy, while the 3 Para Division was to take part in the attack, echeloned in depth and toward the left, pushing in the direction of Manderfeld.

At noon 17 December, the Army believed that the breakthrough of the 12 SS Panzer Division past Büllingen and the south border of Malmédy would be successful, and had given orders in the afternoon to the II SS Panzer Corps that the 9 SS Panzer Division be ready for the march, and that the road across Losheim be reconnoitered for this division. The 9 SS Panzer Division, if necessary, was to be committed on the left side of the 1 SS Panzer Division, under command of the I SS Panzer Corps, for an attack past Losheim, Amel (Ambleve) and Vielsalm. St. Vith was to be bypassed, because it was considered as the first objective of the enemy bombers. The intention of the Army was, regardless of actual attachments and plans, to win space to the west.

Since 0930 hours, the enemy artillery activity was stronger than on the preceding day, but our artillery could break up the infantry effectively from the new position. On 17 December, the enemy air activity was not appreciably stronger than on the day before. However, it was evident that the difficulties of the terrain for our advance were much more important than expected.

On a very muddy and hilly terrain near Büllingen the 12 Volks Grenadier Division met strong enemy forces with antitank guns and several tanks, and till the afternoon did not advance past the hills south of Büllingen. The I SS Panzer Corps reported that roads to bypass such resistance were reconnoitered. No further reports were received from the 1 SS Panzer Division, because the staff was on the march. In order to receive more rapidly messages from the I SS Panzer Corps, the Army had already sent out a liaison radio station, and sent another armed radio detachment immediately after the 1 SS Panzer Division.

Through an air force liaison officer radio communications existed with the parachute group von der Heydte, although other communications were not yet possible.6 Several assault detachments of the ‘Operation Greif’ were operating in the enemy rear zone. The 2 Panzer Division (5 Panzer Army) in their attack north of Bastogne, and the LXVI Army Corps, bypassing the Schnee-Eifel with two foot divisions, made good progress.

On the whole, the enemy situation was as expected. The enemy had not reckoned with such a strong offensive which evidently had provoked a great confusion. Except some isolated combat teams (east of Elsenborn and Büllingen), the resistance was not very strong. Concentrated artillery fire under coordinated direction was not yet applied and there was only isolated commitment of enemy air force over the front. However the supply troops reported strong air activity in the rear zone that prevented the bringing up of the supply. On 17 December, however, these raids had no influence on the supply of the troops. The objectives, planned by the High Command, were not yet attained, but there were no reasons for worry. The Army had expected great difficulties for the first days, and believed that the Maas could not be attained before the evening of the 3rd day.

18 December: The LXVII Corps had advanced forward very slowly with the northern combat team. The roads were mined and obstructed with tree blocks and mines. Enemy resistance gradually became more fierce in the path of these divisions.7 It was clear to the Army at this time, that the expected goal – breakthrough on both sides of Monschau and the cutting off of the road Monschau–Eupen – would not be reached. The Army found it impossible to reinforce this Combat team. Because of a series of train destructions, an expected heavy Panzerjäger battalion did not arrive.8 The Volks Grenadier Divisions were too weak for this type of attack and were not sufficiently reorganized.

It contented the Army however, when these divisions blocked off the forest exits of the Hohes Venn on both sides of the road Eupen–Monschau, and closed in the Americans who stood in readiness for an attack in the direction of Urftalsperre–Euskirchen. A solid block in the sector of Monschau was important to the Army, as it was not possible to have a successful engagement step by step in the heavily impassable wooded country. The attempts, to win the roads from Monschau to Euskirchen to the camp at Elsenborn, and from there the roads from Büllingen to Weismes, were continued in cooperation with 277 Volks Grenadier Division, which continued the attacks near Udenbreth.

The 277 Volks Grenadier Division advanced well forward on 18 December, and took the heights north of Wirtzfeld. With this the Division was freed and together with the 12 Volks Grenadier Division could attack in the direction of Elsenborn. This was ordered for the 19 December. The attacks – Monschau and Elsenborn – had to be under the direction of LXVII Corps.

The 12 Volks Grenadier Division had together with the 12 SS Panzer Division taken Büllingen after a hard battle. Both divisions fought for the village Bütgenbach against a strongly defended enemy, who for the first time attacked with tanks. The 3 Para Division was over Herresbach–Heppenbach. The 1 SS Panzer Division had taken Trois-Ponts and was advancing. The weather cleared about noon. Employment of allied air forces began to develop. As was later seen the spearhead of the 1 SS Panzer Division was attacked.

It was important for the Army to support the 1 SS Panzer Division to win further terrain to the west before the enemy succeeded in bringing up stronger forces, and to prevent the building up of a solid defense front eastwards or westwards of the Maas. The enemy counteroffensive started about noon on the 18th. From intercepted radio broadcasts of the American MPs, it was to be seen that troops movements from the sector of Aachen in the direction of Verviers and eastwards of Lüttich were beginning. The movements of the troops showed obviously that besides an Armored Division only Engineer and antitank guns battalions were on the march, that the objective was to block off the heights and the wooded terrain east of the Maas, between Lüttich and Namur. At the same time, it was heard that inconsiderate orders had been given against the many civilian refugees which filled the roads.

The Army order for 19 December was: enlarge the breakthrough area on both sides of Monschau and attack with the 12 Volks Grenadier Division and the 277 Volks Grenadier Division, the enemy situated at Bütgenbach and throw him back to Elsenborn. Later, with the 277 Volks Grenadier Division on the left, to establish a solid defense front on the line Monschau–Hohes Venn south of Verviers. Enemy breakthroughs over Monschau to the west and the southwest were to be prevented.

I SS Panzer Corps was to extract the 12 SS Panzer Division and attack with the 12 SS Panzer Division through Malmédy. The attack of the 1 SS Panzer Division was to be supported by all means and the supplies secured. The 3 Para Division for the backing up of the advancing 12 SS Panzer Division is to be committed for an attack over the Möderscheid, Faymonville to Weismes. With this order the Army had the intention to prevent under all circumstances that part of the 1 SS Panzer Division or the 12 SS Panzer Division that were committed in northern direction of Verviers from being engaged on their northern flanks.

The II SS Panzer Corps held itself in further readiness to move off with the 9 SS Panzer Division south of the I SS Panzer Corps. The I SS Panzer Corps informed Army in the night that it was not possible for the 12 SS Panzer Division to start the attack south of Bütgenbach because the road Büllingen, Möderscheid, Schoppen was for the most part impassable because of the mire. The Division also could not pull out its vehicles from the sector of Losheim, and that from here the entire road network was impassable and it would take a day to bring them up. The Corps asked for permission to attack once more with the 12 SS Panzer Division and the 12 Volks Grenadier Division in order to gain the road across Bütgenbach. That was approved, simultaneously an order to the II SS Panzer Corps was given to attack with the 9 SS Panzer Division and to advance past Krewinkel, Wischeid, Andler, Medell, Recht, Halleux or Vielsalm. In case this thrust should succeed, it was the intention of the Army, with the 1 SS Panzer Division and the 9 SS Panzer Division to cross over the Maas under command of the II SS Panzer Corps. Later, after mopping up of Bütgenbach and Malmédy, to follow with the 2 SS and the 12 SS Panzer Divisions under command of the II SS Panzer Corps. The Commander in Chief of Army Group B was in accord with the view of the Army that the 2 SS Panzer Division could be brought up past Prüm, Pronsfeld, Habscheid, and St. Vith. It is also to be taken into consideration, that the 2 SS Panzer Division temporarily would be attached to the 5 Panzer Army. The Army was pleased at the possibility of this solution, and during the night ordered road reconnaissance. The breakthrough of the 2 SS Panzer Division depended upon the freedom of the roads, and on the bringing up of the gasoline supply, necessitated for the bypassing of 2 SS Panzer Division.

For the improvement of the road in the sector of Losheim and south of Bütgenbach a Pioneer Battalion was detailed and put under the command of the Chief Engineer of the Army.

Unfortunately, the road repair Construction Battalion from the TODT organization did not leave for this important work until after great delay.

The weather was foggy, the enemy air force only made isolated attacks, and no larger action developed. Unfortunately the ground began to thaw in the early morning hours and the roads and trails then became marshy. The night hours were not cold enough to cause a refreezing of this mud and mire.

19 December: On that day the enemy countermeasures were quite obvious. The enemy resistance against the LXVII Army Corps was growing. Counterattacks were made in the north. The terrain captured during the preceding days had to be given up. Kalterherberg, south of Monschau, was taken. The 277 Volks Grenadier Division reached the road Forsterei Wahlerscheid–Rocherath. On the whole, no perceptible progress was made. On 18 December, a Volksartillery Corps was attached to the LXVII Army Corps and was moving up to the new positions.

The 12 SS Panzer Divisions and 12 Volks Grenadier Division of the I SS Panzer Corps could not advance against the increasing enemy forces. The terrain being very muddy, the infantry advanced only slowly, and the tanks could not be committed off the road. Enemy antitank guns and tanks were well emplaced. Stronger artillery fire and the difficult terrain would probably prevent our breakthrough past Bütgenbach, because it was no more possible for the attacking forces to move into the assembly positions. Evidently the two divisions did not find the appropriate terrain for the attack, the battalions could not advance on the muddy ground and had to use the roads, where they were exposed to the enemy artillery. The heavy enemy artillery fire temporarily caused much disorganization within the two divisions. Tanks, that during the morning hours had found a bypassing road south of Bütgenbach, broke down in the mud at the west end of the village and only at night could be removed from there with great difficulties. A further advance was impossible with these ground conditions. Therefore, the Army gave order in the afternoon that the 12 SS Panzer Division cease the attack, be extracted rapidly and assembled in the area Baasem–Losheim–Manderfeld, and be sent either after the 1 SS Panzer Division or the 9 SS Panzer Division.

The 3 Para Division had well advanced (obviously they met upon weak enemy forces that fell back at their approach) and their advanced echelons had reached Schoppen. The Corps was given order to veer with the Division and to take Weismes. This operation would have relieved the divisions that attacked near Büllingen, and besides the relief of the 1 SS Panzer Division, the establishment of a key point for a defensive front toward north would have been possible.

The division either did not understand the importance of this order or the division was not brought up rapidly enough. The enemy occupation of Weismes (on 20 December) was strong, and the division was not strong enough to take it.9 They did not advance farther than Faymonville. The 1 SS Panzer Division had pushed past La Gleize toward Stoumont and taken Cheneux. At noon the armored spearheads were attacked by enemy fighter bombers. With the advance of the 1 SS Panzer Division, the difficulties of the Hohes Venn, in spite of the bad road conditions, were overcome. This success had to be exploited rapidly. Therefore, the 1 SS Panzer Division was given order to continue their forward movement, fanning out on a wider front, and the I SS Panzer Corps was to secure the gasoline supply.

In the evening it was reported that the Kampfgruppe Peiper, advanced combat team of the 1 SS Panzer Division, had been attacked, and that also the parts that were following, were engaged against enemy forces, that had pushed past Spa toward La Gleize. It was possible now, that not only the Kampfgruppe would be cut off, but that the entire 1 SS Panzer Division would have to turn north against the approaching enemy forces.

The Corps gave an order to keep contact between the 3 Para Division and the Kampfgruppe and to commit a mobile security detachment in the line west of Faymonville, south of Malmédy, in order to protect the flank and to reconnoiter toward north. The reconnaissance detachment of the 12 SS Panzer Division [Kampfgruppe Bremer] and the supply troops were to be employed for this security mission.

The Army considered the possibility of committing the 3 Para Division for the flank protection on both sides of Malmédy, but then made a different decision because:

a. The important road Weismes–St. Vith would thus be clear for the enemy.

b. The parachute division had not arrived in time.

If possible, all the fighting parts of the division were to be relieved, far out on a wider front and to be committed for an attack on Stoumont. It was important to act rapidly and to overcome the difficulties of the roads.

Evidently, the command of the division did not keep the contact with Kampfgruppe Peiper, or their reconnaissance activity toward north was not sufficient, because they believed that the 12 SS Panzer Division was advancing on their right side.

As an exact copy of the orders for the ‘Operation Greif’ had been captured by the enemy, the bigger part of the reconnaissance detachments of this group could not be committed, and the planned surprise action against the enemy units could not be carried out. No contact could be established with the Parachute group von der Heydte.

At noon, the II SS Panzer Corps was given order to move up the 2 SS Panzer Division past Prüm, Habscheid, St. Vith (if 15 Army decided), otherwise past Habscheid, Burg Reuland, Bochholz. Army Group B had the intention to commit this division either with the 5 Panzer Army, or only to move them up to their sector and to attach them to the 6 Panzer Army. In the sector of the 5 Panzer Army the roads were better and would facilitate the commitment of the 2 SS Panzer Division at the side of the 9 SS or even beside the 1 SS Panzer Divisions. This movement, however, could not be accomplished in time, because the Führer Begleit-Brigade and the 116 Panzer Division blocked the roads south of St. Vith. The 2 SS Panzer Division could only be committed in the morning of 23 December.10

Enemy situation: Several days had passed before the enemy started to take countermeasures. From intercepted radio messages we know that:

a. a defensive front was to be established west of the Maas;

b. advanced obstacle construction units (engineers, antitank units and some tank detachments) were to be committed east of the Maas between Verviers and Dinant;

c. units from the area of Aachen were moving up for commitment against the north flank of the Army.

As long as the weather prevented a stronger enemy air activity, it was still possible to break through the enemy defensive front, that was being established, and to destroy the enemy armor. The advantage of the Allies – better vehicles and a greater number of divisions – could be eliminated by rapid action and the greatest efforts.

20 December: The enemy resistance on both sides of Monschau was increasing. Assault detachments, that had crossed the Laufen-brook (north of Monschau) and the Schwalm (southwest of Monschau), had to be withdrawn. The LXVII Army Corps with the 277 and 12 Volks Grenadier and the 3 Para Divisions had taken to the defensive. This defensive front extended approximately in the line Simmerath – east of Monschau – Schwalm – Hill 475 (east of Kalterherberg) – Hill 550 northeast of Elsenborn – Wirtzfeld – south of Bütgenbach – Hill 557 (north of Ondenval) – Baugnez – Stavelot. It was important for the LXVII Army Corps to hold this line, because otherwise the supply of the 1 SS Panzer Division would become even more difficult. Manderfel and Möderscheid were already under intermittent artillery fire.

The 3 Panzer Grenadier Division was brought up to the Army in order to be committed near Elsenborn, if required by the command. The advanced parts of this division arrived on 21 December near Sistig. Without reinforcement, the 12 Volks Grenadier Division could not make a further attack near Bütgenbach.

The 12 SS Panzer Division was in the area assigned for the assembly. However, the bad roads delayed the assembly of the troops that was accomplished only on 23 December. A comparatively high number of tanks broke down during the operation. Orders for their repair were given immediately. The vehicles, many that had seen extensive use during the long war and often had unskilled drivers, were not always satisfactory.

The 1 SS Panzer Division, on 20 December, could not establish the contact with their advanced Kampfgruppe Peiper, that was being attacked by strong enemy forces and, during the night 20/21 December, had to withdraw to Cheneux. Nor was it possible to bring up the gasoline supply to this combat team by road. Therefore supply by air was requested. The I SS Panzer Corps had ordered the regrouping of the attack groups of the 1 SS Panzer Division and expected the success of the attack, that was to establish the contact with the Kampfgruppe the next day. Again it was quite obvious, that the terrain did not permit the commitment of tanks off the roads. Isolated antitank guns and tanks, dug-in at road crossings, often prevented any advance on both sides.

The II SS Panzer Corps was on the march. The 9 SS Panzer Division had a long delay at a blown up bridge near Andler. They advanced dismounted and mopped-up the north sector of the forest of Ommerscheid, where some enemy forces were still situated. The march on the muddy terrain and the carrying of the heavy infantry weapons and ammunition exhausted the troops completely.

The 5 Panzer Army, that had the possibility to advance with their right wing, took Born (north of St. Vith) with the Führer Begleit-Brigade. This success and the advance of the LXVI Army Corps cleared the enemy from St. Vith. Thus an important road junction in the left Army sector could be utilized. St. Vith was not to be occupied, because strong enemy air raids on this town were expected as soon as the weather changed. An engineer construction battalion was brought to St. Vith, in order to secure the passage or the outflanking of this town.

The Army expected that the 1 SS Panzer Division would break through again, and intended to attach the 9 SS Panzer Division to the I SS Panzer Corps. It was also suggested that the Führer Begleit-Brigade should be attached to the II SS Panzer Corps, and that this Corps (277 Volks Grenadier Division and Führer Begleit) should attack south of the I SS Panzer Corps. Army Group B approved of this suggestion, but did not yet pronounce a final decision. The Army recognized that the continuation of the operation in the present direction would meet upon great difficulties:

a. The forces that were to be committed for the isolation of Elsenborn were too weak, even if the 3 Panzer Grenadier Division would also be committed. Thus the advance of our defensive flank to the line Monschau–Spa was in question.

b. We had to reckon with the fact that two more days would pass, before the 9 and 2 SS Panzer Divisions could be committed.

c. In spite of the greatest efforts and the commitment of all available forces, it was impossible to repair the roads in the rear zone, in order to establish an orderly method of re-supply.

Therefore on 20 December, the Army submitted the following suggestion to the Commander in Chief of Army Group B: either to commit all available panzer divisions in the direction of Huy–Dinant, or – and that seemed more appropriate to the Commander in Chief of the Army – to advance north on the good roads Houffalize– La Roche–Lüttich and to push into the enemy defensive front, that was being built up, and in joint operation with 15 Army to attack the rear of the enemy forces situated between Aachen and Lüttich, regardless of the endangered flank at Elsenborn–Malmédy.

The Commander in Chief of the Army Group B did not approve of this suggestion, but wanted to submit it to higher Headquarters. The Army never received an approving answer. Maybe that the suggestion could no more be carried out, because the mobile divisions [9th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions] necessitated from the 15 Army for this attack had been extracted in the meantime and committed in another sector.

21 December: The Army consolidated their defensive front and tried to bring up the panzer divisions as rapidly as possible to the main resistance line. All available forces, even the German civilian population, were committed, in order to overcome the difficulties of the roads. The military police services worked very hard and did an excellent job in those days. In spite of all the orders that were issued on that subject, the troops – Panzer Divisions, artillery, antiaircraft – never got rid of unnecessary vehicles, that were not capable of cross-country driving, especially in the Eifel-mountains, and often delayed all traffic for several hours.11

There was almost no enemy air activity over the sector of the fighting troops, because of the weather conditions, and enemy air activity was particularly strong over the rear zone. Trains, road junctions and supply traffic and dumps were bombed. Between 21 and 23 December, the Command Post of the LXVII Army Corps was bombed and had several casualties but could continue to work.12 These air raids caused sensible delays in the bringing up of the supplies, that often had to be carried out during the night. Moreover, the supply dumps of the Army Group B had to be shifted often and gasoline supply columns, that were already in route, arrived late or not at all. One had to live from hand to mouth, and it happened very often that a tactical success could not be exploited, because the gasoline or ammunition did not arrive in time, or in too small quantities. The fuel consumption per 100 km was much higher than calculated before, because of the bad road conditions. If some of the supplies arrived at all in the main resistance line, it was due to the untiring activity of the truck drivers and the energy of the staff of the supply services.

The LXVII Army Corps was regrouped for the attack against Elsenborn. The troops were to attack Weywertz as follows: Parts of 246 Volks Grenadier Division past Kalterherberg, the 3 Panzer Grenadier Division and 277 Volks Grenadier Division across the road Foersterei Wahlerscheid, Rocherath, the 12 Volks Grenadier Division and parts of the 3 Para Division past Bütgenbach. Then in a joint operation, these forces were to push past Elsenborn toward the road Sourbrodt, Weismes. The attack was scheduled for the 23 December. On 22 December, parts of the 3 Panzer Grenadier Division were to be attached to the 12 Volks Grenadier Division.

The 1 SS Panzer Division had not succeeded in establishing the contact with Kampfgruppe Peiper, which was heavily attacked and encircled in a sector that was comparatively narrow. This made even a supply by air almost impossible.

The 12 SS Panzer Division was still assembling. The II SS Panzer Corps and the 9 SS Panzer Division were advancing past Recht toward the Salm-sector. The 2 SS Panzer Division that originally was to be attached to the 5 Panzer Army, was moving toward Bochholz. The march was delayed, because the division was stopped several times by march columns of the 116 Panzer Division and the Führer Begleit-Brigade.

The Parachute Group von der Heydte was instructed by an air force liaison officer, that the contact could not be established, and that the commander of this group was to fight his way through to Monschau (several messengers had re-joined friendly lines moving in the direction of Monschau), or to surrender after having fired the last round.

22 December: The LXVII Corps carried out further preparations for the planned attack on 23 December. Besides some local thrusts, enemy attacks did not materialize. Only the enemy artillery became heavier, its fire on the road Honsfeld, Möderscheid made it untrafficable. The Army pushed on with the completion of the road Losheimergraben–Honsfeld, Amel.

With the I SS Panzer Corps the enemy pressure became greater, which weakened the attacks made for the relief of the Kampfgruppe Peiper. They did not succeed in establishing contact. The Army ordered the I SS Panzer Corps once again, to free the Kampfgruppe Peiper by all means and to prevent troops and valuable material from falling into the hands of the enemy. Supply by air was not sufficient, and it was attempted to supply badly needed motor fuels by means of armored vehicles.

These attempts also failed. Kampfgruppe Peiper suffered heavy casualties because of the fierceness of enemy artillery fire. As it was later reported, Obersturmbannführer Peiper arranged on 22 or 23 December a truce of several hours, in order to exchange the wounded.13

The II SS Panzer Corps with the 9 SS Panzer Division in their advance on Vielsalm had to march on foot because of the bad roads, while the first parts of the 2 SS Panzer Division had made contact with the enemy at Cierreux. Here, the Army had perhaps a possibility to ‘kill two birds with one stone’ namely:

a. Tear open the enemy defense front on the line La Gleize–Bra–Erezee–Marche.

b. Help the Group Peiper through a thrust over Manhay–Werbomont. (At the same time exploiting the good roads which lay in the northwest direction of the sector Maas–Lüttich–Huy.)

The Army ordered therefore, that the II SS Panzer Corps throw the enemy out by a quick thrust and win the sector Aisne [River] between Mormont and Erezee. It was intended, then with the 2 SS Panzer Division to win further terrain over this sector. The Army figured on the attachment of the 116 Panzer Grenadier Division or the Führer Begleit-Brigade.

The line of separation to the 5 Panzer Army was changed through a new order from the Army Group B, and now ran over Prüm–Bleialf–Samree – along the Ourthe–Andenne [River]. The Army proposed to the Army Group B that the LXVII Corps be placed under the 15 Army, because they were still tied in too far to the rear.

23 December: The attack as scheduled, of the LXVII Corps started in the morning hours. It had, except some local improvements of the front no success. The road Krinkelt–Foersterei–Wahlerscheid was opened and the important heights west of this road were taken in possession. Strong shock troops had also occupied the Hill 598, south of Kalterherberg. They had, however, to give it up again during the night of 23/24 December. The 3 Para Division announced next that Weismes and Oberweywertz were taken. However, this proved to be false. The Army expected no success in the course of the day, from a continuation of the attack on 24 December, because the 3 Panzer Grenadier Division had to be given up to the 5 Panzer Army. The Army proposed to the Army Group B to carry on the attack on 27 December after renewed preparation. The Army had to be prepared for an attack, that would be launched across the line north of Monschau and Malmédy against their deep flank and the supply bases. Therefore, only part of the divisions appointed for the operation could attack, because otherwise the front would have been too much exposed. Only after a very careful improvement of the position could the fighting part of the divisions be extricated.

With the I SS Panzer Corps the situation had developed so that it no longer appeared possible to relieve the Kampfgruppe Peiper from the enemy pressure. The 1 SS Panzer Division was engaged with an essential part to secure the northern flank in the sector Weismes–Stavelot. The necessary motor fuels did not arrive. The Army ordered the Group Peiper to break through the encirclement to the east and to hold the sector directly eastwards of Trois-Ponts. The first part of the 12 SS Panzer Division were moving past Scheid toward St. Vith. Next, they had to be assembled in the sector of St. Vith behind the II SS Panzer Corps. Because of a lack of motor fuel, the march past Prüm behind the 2 SS Panzer Division as suggested by the Army, could not be carried out. The shortage of motor fuels caused especially great difficulties in the period 23/25 December.

The II SS Panzer Corps crossed over the Salm with the 9 SS Panzer Division at Salmchâteau and attacked with the 2 SS Panzer Division over Baraque de Fraiture in the direction of Grandmenil. At Les Tailles and Baraque de Fraiture they ran head-on into an American Armored Battalion.14 From the mentioned shortage of motor fuels, the division was no longer able to thrust further to the west. In the afternoon, the LXVI Army Corps, that had advanced on both sides of the Schree-Eifel – commanded by General Lucht – with the 62 Volks Grenadier Division and the 18 Infantry Division were attached to the Army.