I. PSYCHOANALYSIS AND ENLIGHTENMENT

Dorothy Burlingham’s School

Dorothy Burlingham’s School in Vienna (1980)

WITH JOAN M. ERIKSON

Anna Freud has asked me to tell you about Dorothy Burlingham’s small school in the Wattmanngasse in suburban Vienna. I, in turn, have asked Joan Erikson, who was also part of the staff for a while, to join me in writing this account of how some of us remember this innovative experience.

We believe that to begin with, Dorothy Burlingham as well as Eva Rosenfeld and Anna Freud dreamed the whole idea up together. Dorothy’s four children were then being tutored by Peter Blos, a remarkably craftsmanlike young teacher with clear concepts about how children learn. But tutoring is, of course, individual and isolated learning, and the children lacked the interplay and companionship with other children which a group setting affords.

So a school was formed of children who were spending some time in Vienna—children of different nationalities whose parents were undergoing analysis or who were perhaps in analysis themselves. It was never a very large group, rarely more than twenty children. All the parents, however, were intensely interested in new pedagogic ways and the impact of psychoanalytic understanding on education in the modern world.

This little school, then, was quite a private educational undertaking. The classes met at first in the home of Walti and Eva Rosenfeld and later in a small building constructed for the purpose in the Rosenfelds’ garden. For Eva, this role of hostess of the school (at the beginning, daily lunch was served in her home) was most meaningful in that period following the death of her teenage daughter.

One might assume that such a school would be quite obviously psychoanalytically oriented. In a sense this was, of course, so—but never to the casual observer or in any overly intellectual or modish sense. Dorothy was implementing the best possible school situation which could be devised so it would be congenial to the special needs of English-speaking children living in Vienna and yet also conducive to an atmosphere hospitable to a psychoanalytic orientation. Anna Freud, of course, was discreetly omnipresent in the whole improvisation.

Peter Blos, who became the director of this enterprise, had learned about and become impressed by the kind of curriculum then known as the Project Method which had revolutionized various school systems (first, we think, in Winnetka, Illinois) in America. This educational approach was in accord with John Dewey’s theory that children learn only where their interest is fully engaged and centered. They are then amazingly capable of drawing all the facets of learning the mandatory “three R’s” into the focus of a given project and of mastering otherwise dreary-to-learn skills.

So we taught by the Project Method. The whole school would for a time become, for example, the world of the Eskimos. All subjects were then related to Eskimo life—geography, history, science, math, and, of course, reading and writing. This called for an ingenious combination of playful new experience, careful experiment, and free discussion, while it conveyed a sense of contextuality for all the details learned.

A Christmas Journal carefully designed by the children in 1929 (a copy of which was sent to us by one of the children, Professor Peter Heller of Buffalo) is introduced with an overall statement of the teachers:

Since the beginning of this school year our work has been newly divided. The basic subjects (math, geography, Latin, languages) are taught every morning in the first two hours. The rest of the time is dedicated to “free work” and English. Every two weeks the teachers outline in big strokes a new theme for the “free work” which is then elaborated by the students with the help of books, pictures, and models. At the end of the second week every student reports on his work, be its emphasis geography, history, nature study, or physics, the most important aspect of which is noted down in a summary way by all students.

This statement is followed by an unbelievable list of themes worked on during the three concluding months of that year by students aged 11 through 14. In one of the individual essays there is a remark which throws some light on the functioning of one of us as a teacher-artist: “To illustrate the lessons Herr Erik drew so many posters that by the end of the year they covered all of the walls.” We may add that the journal contains a number of the children’s woodcuts (Herr Erik’s specialty) which markedly illustrate their “themes.”

Since “doing,” itself, is a vital component of the Project Method and the skills of the different aged children had to be carefully brought into play, the little school was a veritable beehive. The children loved it, and they and the teachers learned a good deal. There were also trips into town to see whatever was to be seen of things related to the project, and art and music had an important place in it all. The Christmas Journal also notes that from time to time August Aichhorn would come for some free discussion with the children. In our memory, we experienced that rare joy which is evoked where a setting permits us to respond to the growth potentials of young people as they reveal and develop our own potentials.

Let us now share with you two more personal memories of the school experience which attest to the free spirit which prevailed in the setting. After our marriage we lived on the Kueniglberg, above the school. When our son Kai was born (after some time out for Joan) we daily carried him between us in a laundry basket to the tiny schoolyard or the Rosenfelds’ back porch. It became routine that the children would tell us during class when he was crying (“Kai weint”), and in the intermission some watched him being nursed. It was enriching for us all to share this experience.

And there was a memorable old English Christmas—Yule log, carols, acrobats, dancers, and a boar’s head and mistletoe—at the Burlinghams’ house, and “the Professor” appearing to watch it.

In what respect, then, was this a “psychoanalytic school”? One was aware of some of the children’s near-daily appointments. Not infrequently, one was told that this or that child was “having a difficult time,” and some reasons for it were sometimes discussed in staff meetings. But otherwise, there was hardly any clinical talk, and certainly no individual interpretation. In this connection, however, it must be reported in this account that observations made at the school provided themes helpful in psychoanalytic training and suitable for early psychoanalytic writings. They illustrate, we think, how psychoanalytic awareness can inform the staff and enrich such a school’s work pedagogically. One of these papers is, in fact, based on a role which Dorothy Burlingham played in the school in her inimitable fashion. She would appear a few times a year to ask the children to freely answer a question in writing such as, “What would you like to be, if you could choose it?” or “How are you going to educate your children?” or “What would you do if you suddenly were alone in the world (that means without parents) and would have to help yourself?” One can learn much from the imaginative answers given to such questions. In regard to the last question, however, we felt that it was really not quite necessary for the children to respond as “psychoanalytically” as they did: twelve children described in detail the death of fifteen parents, three of whom were murdered, four died in accidents, and two in prisons. To paraphrase Nietzsche, the children had spent more time describing from whom they wanted to be free than for what. But maybe there was another factor at work: How could the children imagine so suddenly to be “alone in the world,” without parents, except because of violent events? And, of course, there was very much else in these essays.

Kai

Jon

Mikey

Tinky

Bob

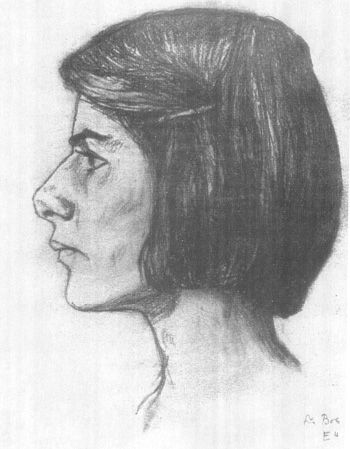

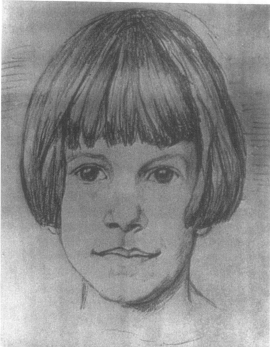

Marie (an older sketch from the Black Forest)

Another paper was based on some sessions Erik had during two successive years with a seven year old boy whose mother felt that he was asking her questions under a certain pressure: what did he “really” want to know? To give an illustration, the first questions in the second year were:

“I don’t know whether I should ask about people or the world.”

“What about rain?”

“And what about the sun?”

“How about ships—do they bump underneath?”

“But you told me all that before and about trains and fire too.”

All the questions were answered briefly and clearly, while no interpretations were given. But a careful comparison of the questions asked a year apart indicated the fate in the boy’s mind both of the questions and of the answers and permitted some insight into the inner processes which determined that fate. At the same time, the whole procedure seemed to confirm Freud’s conclusion that “. . . little Hans’s case shows the importance of letting children express repeatedly, in conversation and in play, their questions about, and their conceptions of the world. The history of little Hans proves that more than half the battle is won when the child succeeds in expressing itself.”*

This last paper (which, incidentally, was entitled, “Psychoanalysis and the Future of Education,” indicating that young as we were, we expected our work to have a pretty decisive impact) also refers to a discussion with our twelve and thirteen year olds about rage and asocial behavior as well as about cultural uses of aggression such as the Eskimos’ singing contests where the goal is for each contending group to outdo the other by making the most devastating fun of it and make everybody laugh. Here, the children made a strange confession:

One of them said, “In the other schools it was fun to pin a paper on the teacher’s coat. Here there’s no fun in it anymore.” We were too nice!

In this memorable little school the children, no doubt, did learn many things. The teachers, however, observed unforgettably what Freud called the “strahlende Intelligenz” (the “radiant intelligence”) displayed by children who for some moments are permitted (by themselves and by circumstances) to function freely.

Psychoanalysis and the Future of Education (1930)

Of all those who through their analytic training hope to be able to make some fundamental contribution to therapeutic or educational work, the teacher is the least able to foresee what he may achieve through analytical insight, which he gains from his own clinical analysis. The analytic situation does not offer him any direct suggestion as to how to face the specific situations he meets on returning to his work. An analyst is obliged for the most part to remain a silent observer while the teacher’s work involves continuous talking—this fact alone roughly distinguishes the methods of analyst from that of teacher, representing the two extremes of all possible educational methods of approach. The clinical analyst maintains an attitude of impartiality throughout, thus making it possible for his patient’s affects to reveal themselves according to their own laws and in the forms given to them by a pitilessly selective life; the passivity of the analyst is the necessary prerequisite for the proof of the scientific value, as well as for the therapeutic success, of the method. In the work of the teacher the relations are much more flexible. He not only has to deal with affects in his children, the ultimate forms of which are not yet fully determined (a feature also found in child analysis), but he also cannot avoid registering his own affective response. Although he is the object of transference, he cannot eliminate his own personality, but must play a very personal part in the child’s life. It is the x in the teacher’s personality which influences the y in the child’s development. But, unlike child guidance workers, he accomplishes his educational purposes chiefly through the imponderables of his attitude in the pursuit of his work as teacher. There he finds the specific means for exerting his influence. His duty is to train, to present, to explain, and to enlighten. Therefore he should ask himself not where his work touches on the work of the analyst or the worker in child guidance, but where and how it in itself gives him the opportunity to make use of his new knowledge of human instincts.

Let us discuss enlightenment, taking the word first in the narrower sense of sexual enlightenment, and then let us inquire where and how this touches the problem of enlightenment as a whole. In the problem of sexual enlightenment, teaching and psychoanalysis can be seen to come to a fundamental convergence.

Some years ago, when I was engaged in teaching, the mother of a seven-year-old pupil of mine asked me to talk with him. She said that Richard revealed such a drive to ask questions about everything that she felt unable to satisfy his curiosity and she preferred to have a man answer his questions concerning sexual matters. I spent several afternoons with Richard. He asked questions and I answered; we talked about God and the universe, and where children come from. Every question was answered conscientiously. Richard was a very intelligent and receptive boy. One rule proved to be important—namely, never to give more information than was asked for. His questions ventured to the point of inquiring about the man’s role in begetting children and there they stopped. He did learn, however, that the semen of the man enters the woman and that this makes it possible for her to bear a child.

One year later Richard again expressed a wish to ask questions. As soon as he began, however, I noticed a certain reserve. His questions were no longer eager and punctuated with large question marks; they rather took the form of statements—whispered, careful statements. I again answered him conscientiously but with enough reserve so as not to disturb the next question already formed in his mind. The continuous flow of his questions was not interrupted. I took notes during the interview, explaining that we would use them later to check up and make sure he had omitted nothing. The following are his questions, with tentative analytical interpretations. Let me state, however, that I interpreted nothing to the child. Throughout the interview I remained the teacher whose place it was to answer questions.

Richard’s Questions

THE FIRST HOUR

“I don’t know whether I should ask about people or the world?”

“What about rain?”

“And what about the sun?”

“How about ships—do they bump underneath?”

“But you told me all that before and about trains and fire too.” PAUSE.

The little scientist would like to keep far away from the interesting and the dangerous world of people and remain with atmospheric phenomena. When, however, he does discuss men, he circumscribes a wide circle around the genitals. But increasing pressure from within leads him to associations which touch on an inner anxiety. At this point, as at the word “fire,” he pauses. The reason will soon become clear.

“How long can a diver stay under water?”

“Must he always pump?”

“What does he do when he wants something?”

“Once someone made a man. Why did he spoil him again?”

“I heard that a house was burned and everybody who was in it.”

“But—when a prison burns? Are there windows in prison?” PAUSE.

Again at the mention of “fire” comes a pause. In the depths, in prison, in a burning house—one cannot call, cannot breathe, one burns. A man was made and then destroyed again. We begin to see that these associations have something to do with a narrow room in which a man is made—revealing to the analytic eye an unconscious fantasy and anxiety about the womb and the child it contains.

“I’ve never seen a house burning.”

“I’ve never seen a fire engine burning on a house—that must be fine but not nice.”

The fantasy which was restrained before each time by silence now comes to the surface. It does so by means of a slip—the fire engine is burning instead of squirting water. The dangerous sensation of “burning” has replaced the pleasantly harmless and “manly” activity of the squirting fireman. The deeper meaning of this slip becomes clear later.

“After all I think I’d rather ask about people.”

Apparently he does not know how much the inner voice has already asked about man. It would be interesting to know if and how the slip itself made this daring question possible.

“What about cars?”

“How can you talk?”

“How does hair grow?”

With the word “hair” he loses his wish to question further for the day. At this point I remember that already, the year before, a group of questions were always recurring which no answer satisfied—they dealt with “hair” and “blood.” These probably were the expression of the deeper question whether the blood, which he had doubtless seen on the clothes of a woman as she undressed, signified the castration of the male organ or if the latter were only hidden by the hair.

These questions, according to their tone and content, form two special groups and may be classified as follows: (a) simple questions of interest, which seem to be only a kind of pretext, and the answer to which he already knew by heart; (b) the “hair and blood group,” repeated from the first year, representing increasing anxiety. It is noteworthy that among all the new questions, which are obviously filled with dangerous matters of unconscious sexual meaning, there is not one direct sexual question.

THE SECOND HOUR

“Where does the air begin to get thinner?”

“What’s around the sky?”

“What’s a cloudburst?”

Now we have come back to earth, but along with a suggestion of something unpleasant—namely a cloudburst. Therefore, he pauses. Nevertheless, he makes a courageous decision.

“After all, I’d rather talk about people.”1

“I know everything about the head.”

“About the legs, too.”

“Do I know everything about arms?”

“About elbows too?”

The wide circle around the genitals is worthy of note; but the boy’s anxiety about them bursts through in the next question: “How do you snap back the elbow when it’s come out of joint?” Does “coming out of joint” suggest erection? (Arms and legs are “members,” called “Glieder” in German, while penis is also called a “member or “Glied.”) In any case there is again a pause.

Then follows a still clearer anxiety about the penis. In the throat there is a tube for air and another for food. They must come out somehow below when you put your head down:

“And when food gets into the air tube?”

“Is it like that in a hen too?” (The association “hen” will be explained later.)

“In a snake too?”

“How does a snail push itself forward?”

“Where are there purple snails?”

The tubes that come out below, the snake, the snail that “pushes itself forward,” the purple snail, all point clearly to the penis. The purple snail connects two ideas—snail and blood. Richard had heard the myth of the Greek shepherd who found his dog, bleeding, as he thought, at the mouth and then discovered that the animal had bitten a purple snail. Now, consequently, we approach the fear of “castration,” which, being unconscious, threatens to overshadow everything:

“When you cut off your hand do you have to stop the blood with bandages?”

“When you’re dead does the skin fall off? Do the bones go to pieces?”

“A celluloid factory can explode easily, can’t it?”

The hour began with “cloudburst” and ended with “explosion.”

THE THIRD HOUR

“How fast can a man run?”

“And an animal?” (Does he mean “run away”? It would seem so.)

“I’d like to know something about war. If Vienna hadn’t stopped fighting would it have been all ruined?”

“Who started the fighting?”

“That was mean of England to help against Vienna.”

Here it is necessary to consider what “fighting” and what “England” and “Vienna” mean. For some time Richard had shown occasional timidity on the street. Once, when questioned about his fear, he declared anxiously, “The dogs fight.” A very enlightened little girl, hearing this remark, immediately explained, “They don’t fight, they are marrying.” Now people marry, too, and there are sufficient indications that physical conflict is involved. Many children overestimate these indications, especially in families where physical or psychic pain seems somehow to be connected with the events going on in the parental bedroom. Richard’s mother, who seemed to be unhappy, had married in England, but shortly after the war had been compelled by various circumstances to leave his father and settle in Vienna. Richard explained this change by connecting the war, the fighting and his father, from whose aggression his mother had fled away to Vienna. The unconscious identification of the country in which one lives with the threatened or suffering mother, and the enemy with the brutal father against whom the boy, the young hero, has to defend her may be pointed out as a common one. It is important to see where Richard’s fantasies are based on his special œdipus situation. “The sun and the moon,” he once remarked, “can never be in the sky at the same time. They would eat each other up.”

“How are the teeth made firm?”

“Why are lips so red?”

“Why is the head up straight?”

“When you bend it back it gets all red.”

“Why do you bleed when you cut yourself?”

“The hair under the arm . . .”

References to blood and hair again terminate his desire to question further. The possible interpretations of this hour may, then, be summarized as follows: (1) pitying identification with the suffering mother; (2) the wish to be like her; but also (3) fear of this wish, because becoming a woman means castration. A further anxiety about becoming a woman, appearing in the next hour, demonstrates that we are on the right track.

THE FOURTH HOUR

“In your head there’s an opening. Why doesn’t everything run out?”

“Some people have something here” (goiter).

“Some people have a hunchback.”

“If somebody hits somebody in the eye will he be blind right away?”

“Why are women so fat here?” (breast)

“And how is it when the woman has too much milk and the baby doesn’t drink it all?”

“And when a woman has too little?”

Bursting skull, goiter, hunchback, the overfull breast, the dislodged eye; women grow fat, have children in their bodies and milk in their breasts. How do their bodies stand it? It is now possible to understand the strange intrusion of the “hen” in the second hour. It appeared in connection with the question as to what would happen if food should get into the wrong tube. [If we take] into account the familiar mechanism which disguises unconscious thought or fear by reversing the term used, as for example “below” to “above,” “out” to “in,” the question about the “hen” may mean: what would happen if that which should come out below (the egg from the hen, the child from the mother) tried to come out of another opening which was too small and burst?

At this point it is well to bear in mind Richard’s actual difficulties at the time of this interview. He had attacks of pavor nocturnus in which he cried and asked if his bowel movement had been sufficient. When he was assured that this was the case he slept quietly. As this symptom disappeared he began to have difficulty with eating. His symptoms followed one another with a transposition similar to that of his questions, that is, from “below” to “above.” Both were obviously aspects of the same anxiety: through which organ is the child begotten and through which is it born?

“Why do you see a strong man’s muscles so plainly here?” (The veins of the arm.)

“What part of people do cannibals eat?”

“There were many in the war?”

“Once someone told me about cannibals and I always thought they ran around in the streets.”

“When you stand for a long time your feet get all red.”

These questions are followed by a clear symbolic description of the anxiety about the penis:

“Is there a quite smooth ball here on your knee?” (i.e., gland)

“When you stretch your mouth open why doesn’t it tear here?” (in the corners)

“But when you cut yourself somewhere on your skin, it could go on tearing couldn’t it?”

“There’s a sort of bone around the eye?”

“Why don’t they put armor inside a soldier’s uniform?”

“Are there armored cars in Vienna?”

“Around the neck there’s a sort of skin collar?” (i.e., foreskin).

Again, in accordance with the displacement mechanism, the part most in danger is transferred above, but to a part of the body which also shares the danger of being cut off—namely, the neck.

THE FIFTH HOUR

As this was to be the last hour before the holidays, and as it was preferable not to let the boy leave without any enlightenment in the matter which was troubling him, I reminded him that he had asked no question about childbearing, which had interested him so greatly.

“That’s so.”

“Why is it [women’s buttocks] so fat behind?”

“What happens when the child stays in too long?”

“How do you know when it’s coming?”

“And when you marry then the semen comes from the woman into the man, doesn’t it?”

It is apparent that Richard, who had shown such intelligence in the understanding of all the enlightenment given him up to this point, had nevertheless been unable to maintain his sexual knowledge against the repressing forces. These had led him away from the masculine role and at the same time subjected him to intense anxiety concerning the factors likely to threaten him in the woman’s role. The slip with which he first disclosed this change is noteworthy: the fire engine burns instead of squirting.

From this very limited insight into one child’s mind which Richard’s questions have provided, we may conclude that the formation of anxieties, fantasies, and unconscious and conscious theories continues regardless of sexual enlightenment. It is important to consider whether or not there is reason to believe that the infantile psyche (or, can we simply say the psyche?) always reacts in this manner.

At first the child had asked questions openly. His desire to question was very naturally so divided that his wish for general information appeared in the foreground, while behind it lay his easily accessible curiosity about sexual things. The further development of the œdipus complex brought about a repression of the now dangerous sexual questions. Questions are now set carefully, half dreamily and disinterestedly, and behind the words which would endeavor to hide the sexual content lurks a general permeation of sexual anxiety, born of the conviction that a catastrophe must take place. The grownups, of course, deny or conceal this, but there are too many indications of actual force in sexual life and too many catastrophic desires in one’s own mind. Because of anxiety and one’s own desire for aggression, all signs of aggression become overvalued. These signs are not lacking, since a sado-masochistic component is always evident in the tension of sexuality, even though in normal sexual life, in the general attitude of the adult, it may be balanced and imponderable. In any event the child in his preoccupation overvalues something real. Changing according to his stages of development, his affective relationship to the single components of sexuality is based on what he observes in the outer world, as well as upon the sensations of his own body.

For the adult these components have become imponderables, scarcely measurable in normal sex life, and only in the artificial situation of psychoanalysis is the old scheme of weights and measures temporarily reëstablished. In life, adult and child represent different stages of a development or, more accurately, are the result of different mathematical operations which are employing the same values; the sexual development of a child resembles a gradual addition while adult sexuality is the product of the same figures.

These oral, anal, phallic, sadistic imponderables, however, which the adult can no longer measure or name, are just those which are experienced in crude isolation by the child, one following the other inexorably. The child develops them, fights against them, tries to balance them, and this struggle is complicated by the fact that he is busily occupied with the pleasure zones of his age level (or of an earlier one from which he has only partly progressed), as well as that he experiences sensations which prevent him from grasping what the adult tells. In general, the sexual act as represented to the child is rationalized and made more or less gentle and noble according to the personal attitude of the individual adult. In any case sleeping restfully together is sure to be emphasized by the adult as the only pleasure involved, but it is just this feeling of protected rest from which the child is drawing away into the tumultuous fight for existence. Only yesterday he forsook his mother’s arms and his possessive share of her body. Today he has a respite in which to accustom himself to his loss, but tomorrow, so he feels, something quite new and different and dangerous will present itself. Rest, however, is the reward for his successful battle. He, therefore, accepts sexual enlightenment exactly as he accepts general enlightenment in other fields—passing it off with an almost patronizing gesture and with the feeling (sometimes even conscious): “Maybe you’re right, though you tell me enough lies. But I’m interested in something else, and that you apparently won’t tell me about because you think I’m too stupid—or perhaps you can’t tell me because you’re too stupid yourself.”

An example offered by one of Richard’s classmates may be cited in this connection. He had upon occasion heard from me that children are nursed at their mother’s breast, and very probably he had also had an opportunity to observe this. Nevertheless, he exclaimed one day in school: “You said that women have breasts to give milk, but that isn’t so. What women have there is something to have fun with.” What does the boy mean by “have fun with,” the pleasant appearance or feeling of the breast or the enjoyable vague memory of nursing? In any case, he is not alone in this feeling. But when he asks about it no one appears to know anything, and his confusion and excitement are met with idealistic or scientific conceptions. Here, too, the interest of the child lies in a certain vividly felt emotional relationship, in response to which he is told something about sucking calves and lactating cows. But cow’s teats resemble more nearly a multiple penis to the boyish mind, and the milking he observes very likely brings further confusion and new evaluations. In the face of such emotional relationships, education enforces repression and sets up in their place scientific law and order. We enforce with the patience of the drop that wears away the stone. But is there not ground for reflection when one reads what the laughing philosopher Zarathustra at the height of a gay science offers his fellow men as wisdom? “Es gibt doch wenig Dinge, die so angenehm und nützlich zugleich sind, wie der Busen des Weibes.”2 The philosopher, of course, can rediscover and express the obvious facts which the adult refuses the child.

On the basis of clinical experience, psychoanalysis has recommended sexual enlightenment as of very real assistance, but what the enlightenment presents remains a fairy tale for the affects of the child, just as the story of the stork remains a fairy tale for his intellect. Let us not forget that the stork story does offer the child something. Recently Zulliger [Hans Zulliger (1893–1965), a well-known Swiss analyst] interpreted it as follows: “The complete stork tale, as a more exact psychoanalytic examination is capable of showing, contains anal and genital birth theories (the chimney, the stove and the pond), the idea of the forceful and sadistic in connection with the acts of begetting and bearing (biting in the leg), castration idea (leg biting), the genital begetting idea (stork-bird as masculine symbol), etc.”

Modern teachers forsake the symbol-filled darkness of ancient tales which combined so attractively the uncanny and the familiar, but in doing so they have no reason to be optimistic, for while replacing them with more logical interpretations expressing some facts more directly and clearly, they neglect to include even vaguely much that is more fundamentally important. Neither fairy tale nor sexual enlightenment saves the child from the necessity of a distrustful and derisive attitude toward adults, since in both cases he is left alone with his conflict.

Noteworthy in this connection is the section in The Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy where the child derides his father by means of remarks about the stork fairy tale.3* How dangerous must it then be when, instead of the fairy tale-telling adult or the adult who tries to carry out his theoretical duties, matters are taken in hand by the adult with pretensions of truthfulness or moral gravity.

That the adult who is questioned by a child is in the position to give interpretations seems to be only a first step forward. Above all, the adult must know that consistent and effective interpretation belongs in the realm of clinical analysis. Then, once he recognizes the twofold meaning of the child’s questions, he is faced with two possibilities. He may either ignore the hidden meaning and consequently answer inadequately—perhaps even more dangerously and less adequately than the stork tale—or, disregarding the disguise of the question, he may interpret its hidden meaning, answering more than was intentionally asked. This may prove a shock for the child or, as is more probable, it will remain absolutely ineffective. And few things undermine the position of the adult more disastrously than serious but ineffective effort!

For the teacher there remains another individual problem. He must not only appreciate the sexual curiosity masquerading as desire for knowledge, but he must make the greatest possible use of it. The child never learns more than he does at the time of disguised curiosity. At this time he learns with the cooperation of his affects, and now when he hopes finally to find out “the hidden secrets,” the statement “vita non schola discimus” really holds good, for he is learning now for the sake of the life he dimly divines, and not for the sake of his lessons.

One might think that the teacher could make use of this situation to smuggle into his answer the sexual enlightenment that the child’s questions have unconsciously requested. By general frankness he should be able to establish the certainty that there is nothing more secret about sex than about everything else. However, glimpses into the unconscious, such as described above, show that the sexual questions as they reach a complicated and dangerous point (a moment which enlightenment is supposed to guide) inhibit the desire for further questioning and the wish to learn. Softly the child speaks of the purple snail and fire engines, the food tube of the hen and the goiter that some women have. And still more softly come the inmost questions of the child which only barely make themselves heard to his interpreter: “What about the desire and the fear of destroying, and the fear and desire of being destroyed?” With his most earnest questions, then, the child still remains alone.

Here, besides the limits established by mental and physical development, we meet an affect-barrier blocking openmindedness and readiness to learn. That which the affect has under its power is released only by means of stronger affective experience, and not by any intellectual interpretation alone. Here again the analytic situation in itself meets both requirements: it provides experience through interpretation and interpretation through experience. The teacher is only able to give a carefully selected picture of the world according to his best knowledge, and this is true also of sexual enlightenment.

However, since all early experiences disappear only to reappear later as a powerful stream, we must assume that both the infantile disappointments and the derision or surrender with which the child meets them play an important role in the unconscious life of adult human beings; that because of these childish doubts and despairs “healthy” humanity clings to its group neurosis—its conflict concerning knowledge and faith—just as the neurotic clings to his individual symptoms. It is, therefore, not alone the attitude of the child toward the adult which is touched on by our question, but the attitude of humanity toward itself. The command which one received as a child is passed on to the coming generation, and it is the adult with the repressed doubts who unknowingly increases the confusion of unfruitful belief and knowledge in children who are desirous of learning. This is shown in a practical way by the method used by educators in selecting and arranging the material to be taught. Almost all courses of instruction, from the picture book to the study of history at the university, are as if designed to confuse man concerning his visual, perceptive, and other relationships to himself and his history. After prohibitions, doubt, revolt and surrender have helped to establish the basis of his intellectual life, it is difficult for him to direct his intelligence to the necessity of dealing with the dangers within himself; it is impossible for him to decide whether “to ask about the world or people.” Deciding in favor of the first may often imply the unconscious prohibition of the second—an inhibition in thinking which will naturally also have its consequences for his conception of “the world.”

A broader conception of enlightenment, the expansion of which will undoubtedly arise from psychoanalysis, is needed.

There is a footnote in Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents:

‘Thus conscience does make cowards of us all. . . .’ That the upbringing of young people at the present day conceals from them the part sexuality will play in their lives is not the only reproach we are obliged to bring against it. It offends too in not preparing them for the aggressions of which they are destined to become the objects. Sending the young out into life with such a false psychological orientation is as if one were to equip people going on a Polar expedition with summer clothing and maps of the Italian lakes. One can clearly see that ethical standards are being misused in a way. The strictness of these standards would not do much harm if education were to say: “This is how men ought to be in order to be happy and make others happy, but you have to reckon with their not being so.” Instead of this the young are made to believe that everyone else conforms to the standard of ethics, i.e., that everyone else is good. And then on this is based the demand that the young shall be so too.4

About aggression as well as about sexuality the child hears at best a rationalization in the form of biological, historical, or religious purposefulness and is left alone with his own “purposeless” instinctive energies. He must feel himself alone, wicked in an apparently noble and purposeful world. He must repress the doubt born of firsthand evidence. How could we then believe that sexual enlightenment is sufficient, or, on the other hand, that all enlightenment is useless if sexual enlightenment is not sufficient? As a matter of fact the soul is a melting pot of inimical drives which urge the child from infant into adult life, forcing it through the vicious circle of guilt and expiation. The inwardly directed aggression (the most important psychic reality of civilization) is, according to Freud, best and first recognized in its sexual alloy—but not entirely to be understood in it.

Observing about ten of our twelve-and thirteen-year-old children outside of school and finding in their behavior some thought-provoking features, I determined to have a talk with them. Our discussion began with the explanation on the part of some of the children that much unsocial behavior lay in outbursts of rage—a rage (as they soon discovered) which was often unreasonable. Others soon became clear about the fact that this rage was inwardly directed and that it excluded them from an unconcerned participation in the activities of the group. With this knowledge the analyzed and unanalyzed children then began to show an understanding which would have seemed impossible. As the opportunity arose in the discussion, I was able to give them examples from our history study which corresponded to the feelings we were speaking of. The children had learned facts about the Eskimos5—for example, that they have a so-called “singing contest” instead of law court procedure, whereby the two opponents are forced to make fun of one another until the laughing observers declare one party or the other “knocked out.” A little girl immediately had the correct idea: “They can do that,” she declared, “because they haven’t any nasty names. We would say ‘pig’ or ‘idiot’ right away and then everyone would be mad again.”

Another example of applied history was offered by the story of Amundsen who, during the flight of the Italia, held himself strictly under Nobile’s command in spite of an intense rage against the leader. In short, we discussed examples of rage, justified and unjustified, and examples of the social control of this emotion. With this acceptance of rage as a general fact, that is, as something that is not merely the fault of the individual who carries it within him, a variety of thoughts began to stir in the children’s minds. They spoke of aggression that is displayed and of aggression that is felt, of guilt and the desire for punishment, with an inner comprehension of which adults are hardly capable. They even discovered “civilization and its discontents” in our little progressive school. They admitted openly that their desire for punishment was not satisfied by us. One of them said, “In the other schools it was fun to pin a paper on the teacher’s coat. Here there’s no fun in it any more.” Another declared, “We’re like balls that are all ready to explode and suddenly are put into an air tight room.”

Then we were able to discuss what one should do with this desire for punishment. The Puritans were mentioned—men who though expelled for their belief became the grimmest of religious tyrants as soon as they had the power to exercise tyranny. The older children discovered that their behavior towards the smaller ones represented a tendency to abreact their feelings regarding control by the teachers. This began to make it clear that valuing fairness so much more than mutual suppression, as we did, only one thing was possible—submission through understanding of the situation. Finally the children came to the conclusion that the only thing possible would be to speak often and penetratingly about the force which endangered this understanding from within until it lost its power.

Now, of course, all this is very easily said, but the reactions following such talks are not as easy to predict. This was demonstrated the next morning when, for the first time in two years, two of the older boys fought. I was reminded of Chancellor Snowden’s remark at the London Conference: “Another such peace conference and we’ll have war again.” However, [because we knew] the neurotic condition of the two boys, it was possible to accept as a good omen the fact that they for once actually and spontaneously “went for each other.”

In view of such experiences, one would think that modern education must often stand abashed before its own courage, the courage with which it hopes to lead young people, by means of good will, toward a new spirit and future peace. It is psychic reality which forces itself through, and this the more unexpectedly and unpleasantly the more it is denied. One can understand that many are panic-stricken and, as it were, throw to the winds the ideal of the primacy of intelligence.

Freud has written that an increasing sense of guilt must accompany the development of culture. It is certain that (wherever the temptation to forget what has already been learned is withstood) education will become increasingly understanding. However, experience and theory teach that the feeling of being loved and understood does not diminish the strength of the feelings of guilt but rather increases them, and this brings about an economic discrepancy similar to that discovered by Freud in sexual life when he found that the development of culture had brought with it a shift in the unconscious evaluation of sexuality which made worthless both of the conscious alternatives—asceticism or living out one’s nature. The only remedy for this upset economy is to make unconscious material conscious, and to prevent the accumulation of unconscious material by continuous enlightenment. Apparently pedagogy now faces a similar problem in the question of aggression, guilt and desire for punishment, and perhaps here, too, steps taken toward suppression or liberation will not really touch the heart of the problem.

Perhaps a new education will have to arise which will provide enlightenment about the entire world of affects and not only about one special instinct which, in an otherwise entirely rationalized outlook of life, appears too obscure. This would imply a presentation of life in which the omnipresent instincts “without usefulness” (in reality the instinctive urge that opposes all “use”) would no longer be denied. It is this denial which brings about the hopeless isolation of the world of children with their conflicts.

This isolation, it is true, is frequently overcome, but often only apparently. But the general fact, that the inner enemy is left concealed in darkness instead of having light focused upon him, gives him the power time and again to overthrow the sound will of the individual and the best-made plans of well-meaning leaders.

Certainly men are like this, but have you asked yourself whether they need be so, whether their inmost nature necessitates it? Can an anthropologist give the cranial index of a people whose custom it is to deform their children’s heads by bandaging them from their earliest years? Think of the distressing contrast between the radiant intelligence of a healthy child and the feeble mentality of the average adult.6

It is surely no coincidence that the desire for a science of education should appear on the scene at the moment when, in the form of psychoanalysis, the truth of the healing power of self-knowledge is again establishing itself in the world. And to this truth much has been added since the time of Socrates, namely, a method. If education earnestly seeks to rebuild on a new conscious basis of knowledge and intelligence, then it must demand radical progress to the point where clear vision results in human adjustment. Modern enlightenment can best achieve this through psychoanalysis.

Notes

1 In the [Zeitschrift für psychoanaly tische Pädagogik] V. 7, Dr. Edith Buxbaum describes an experiment with a class of 10–11 year old girls of a public school in Vienna, to whom the liberty was given of asking any questions they wanted to. The girls as a group behaved almost exactly and literally like the questioning Richard. With the first questions they tried to cling to things which led far away, such as telephone, airplane, Zeppelin: “What is it like when you fly up into the sky, on and on, straight ahead?” Then came the opposite direction, “And if you bore down into the earth?,” which led them to dangerous questions—“Why don’t the stars fall down,?” to lightning on earthquake. The latter was explained by one girl as coming when “things which don’t get along together bump underneath.” One girl’s question: “Why do you feel your heart beat?” was unanimously disapproved of by the class. And still they seemed to be waiting for something. When a girl asked: “Wie berwegt sich der Mensch?” (“How do men move?”, half the class understood: “Wie entsteht der Mensch?” (“How are men made?”)—and giggled. But finally they admitted just as Richard did: “After all, we would rather ask about people.”

2 “Indeed there are few things which are at the same time as pleasant and as useful as a woman’s bosom.”

3 Though it seems rather hopeless to succeed in giving children the biological truth while they are concerned with the reality of affects, little Hans’s case shows the importance of letting children express repeatedly, in conversation and play, their questions about, and their conceptions of, the world. The history of little Hans proves that more than half the battle is won when the child succeeds in expressing itself.

4 Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (New York: Jonathon Cape and Harrison Smith, 1930), 123–24.

5 Included under project work directed by Dr. Peter Blos.

6 Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion, tr. W. D. Robson-Scott, (London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1928), 81–82.

Children’s Picture Books (1931)

At our Montessori seminar we reviewed a number of highly diverse picture books. Our ultimate impression was that on the whole, they constitute a small, circumscribed world that reflects the big real world—with specific distortions. This I would like to document in psychological terms although the great variety of books may at first be confusing. We looked at the ominous Struwelpeter with its magical drawings, the pictures of toys in powerful colors, and some of those strange pages that delicately render a pale, sweet, mimosalike world.

Aside from all these, one bright genre of writing shone clear: the irresistible humor of Max and Moritz and Adamson. These books are not aimed directly at children; their mature humor addresses any receptive human being. We will discuss them later.

Let me first single out a critical word that I hear frequently. Struwelpeter is supposedly “sadistic.” Yet this adjective must have a somewhat different meaning when applied to a different type of book. I am referring to a picture book that seeks to deplore animal torture by showing a tortured creature on every page. Obviously such depictions tend to stir up cruel impulses rather than revulsion. Struwelpeter, in contrast, presents not only scenes in which a creature (a creature identifiable with the child reader) is tormented but also some in which a child is punished. We all expect that any reader will identify with the hero of a book. So we may conclude that the children reading this book feel punished when Struwelpeter is punished, and we know how lasting such an impact can be, and how unforgettable the perverse enjoyment. Even terrified children return to this book.

We recognize here two interpretations of the word “sadistic”: not only “cruel to others” but also “cruel to oneself”—a far more dangerous interpretation, as we shall soon understand. For cruelty to others is checked by the strength of those other living creatures, who defend themselves. But what is it that curbs the paradoxical tendency to be cruel to oneself? I will say a few things about this later on, for it seems to me that if we condemn certain effects, we should try to recognize their root causes. Otherwise, they will return along unforeseen paths.

We ask ourselves: Why is it that adults draw cruel or childish pictures for children’s books? And why do children feel joy and comfort at seeing themselves depicted as punished or excessively childish and saccharine? If we tell the artist that he doesn’t know how a child sees the world, he will merely cite the appeal of his drawings and suggest that artists probably know more about children than we do. This seems to be true in some way, and we have to try to find the common ground that draws them together, the artist and the child.

I would like to digress for a moment and point to certain medieval paintings that are not difficult to find. In some depictions of the Mother of God or the Holy Family we see, among the mature, tender human faces, that the countenance of the little Savior or other children are strangely distorted: ill; somewhat embryolike; somewhat senile. One might initially believe that the Christ Child was meant to be depicted as an “old infant,” mature at birth and childlike in death. Yet we cannot help feeling that here the adult artist, ascetically and mystically earnest about the true nature of childhood, has unconsciously shrunk back, refusing to recognize a child as he really is. The manner of distorting the child in order to contrast him with the Holy Mother is a special problem. What we are looking for in this phenomenon is one more symptom of a conclusion that forces itself upon us in picture books, too: that there is a general tendency to distort, to deny childhood.

In reality the very young infant certainly evinces nothing of this. He delights in himself and in the growing radius of his movements and impulses. His psyche seems to say, “This is good,” to everything that he produces with his body and perceives with his senses. And he is used to having the big people (the powerful adults on whose love he depends) applaud his behavior—until he reaches an age at which he can be educated. Now, when he comes out with his most genuine and favorite behavior, adults more and more often state emphatically, “You mustn’t do that. We won’t love you when you’re like that.” Thus the child learns that certain action is not generally lovable. He has to find some way of maintaining his old self-love (which is necessary for human survival) while also keeping the love of adults, which he needs just as badly.

This solution operates (according to the research of psychoanalysis) as follows: The child condemns some of his impulses on his own; by some enigmatic mechanism, he internally develops an authority that appropriates and represents the prohibitions of adults. One part of his ego is transformed—psychoanalysis then calls it the superego—and repudiates the part that remains as it was originally. The positive aspect of this development is that the prohibiting part, too, belongs to the child’s mind, representing the prohibition as his own desire, with which his self-love can side. But such disparate self-love survives at the price of one’s inner unity.

The child likes himself now insofar as he, like the adult, has learned to watch over his thoughts and deeds. Thus he develops an often puzzling mechanism deciding what is “good, well behaved,” and he enjoys picture books in which good children are rewarded and bad ones punished. And so it comes about that while he may very recently have hated much younger children, whom he saw as rivals, he now finds them “sweet, cute,” at the urging of his inner authority, and enjoys sweet picture books that we would find silly and would rather keep away from him.

However, the adult who drew these pictures for him long ago went through the same transformation and experienced something highly important to boot: He then forgot what had happened. “ ‘I did this,’ my memory says. ‘I cannot possibly have done this,’ my pride says, and remains adamant. Finally, the memory gives in” (Nietzsche). Thus, repressed childhood wishes are replaced by paradisiacal surrogate images or moralistic prejudices, as though one had been born a well-behaved creature. The adult (impelled by some urgent memory) feels the desire to draw a picture book for the child. He either establishes good and evil in his book or makes up a world of such doll-like infantility that it is without punishment only because it has no drives. Because of this connection, I can explain why I initially refused to be distracted by the difference between the punishing books and those books that use a delicate or schematic depiction to strip the world of flesh and blood. The former books show the world as threatening and advise caution; the latter advise capitulating immediately to the threat by behaving like a doll or a delicate mimosa, the kind of child so many adults like to see.

The advantages in the mechanism of conscience formation are obvious: The child catches up in a short time with thousands of years of upbringing. The natural creature of drives turns into a being with a twentieth-century conscience. The entire heritage ready for this development is now manifest. And the energy underlying the first instinctual expressions is now employed for purposes of general usefulness; it is integrated in mankind’s efforts to endure its alienation from nature and to compensate for it. People accept this development without further ado, saying, “A normal child doesn’t suffer all that much from this process.”

I must therefore introduce the fact that the disadvantages of this process present us with our actual theme, leading us directly to an important pedagogical problem. For these disadvantages are great as they pile up with the growth of civilization. They threaten to turn into the mountain with which modern education, after a bold approach, finds itself unable to cope.

Let me repeat what we have said: A child can be educated because of a split in his mental makeup. Under the pressure of the alternative—forgoing love and protection—between remaining what he is or becoming like the adult in order to please him, the child undergoes a transformation in the psyche. An inner voice arises, taking over the prohibitions of the adult milieu and making sure that the child’s instinctual energy is tamed and, whenever necessary, punished for unruliness. This authority, as we have said, censors all memories of the original and now-condemned world of the senses. The page of the psyche is blank again—not because nothing was written on it but because the censor has meticulously pasted over the primeval writing.

Now we have only to emphasize the distinct differences between the external prohibiting power and the internally established authority in order to recognize the danger of this inward shift. The internal authority becomes an absolute dictate and no longer a human being. A human being sees in another only what circumstances allow him to see: seldom his thoughts; never his unconscious feelings. But the conscience apprehends everything and finds even the most unconscious things punishable. A human being can be lenient when he sees that his prohibitions go too far or are made invalid by changed conditions. But the inner dictate is not the likeness of such a changeable person; it is only the reflection of his earlier, perhaps joyless and unperceptive admonition. (How many perceptive now-modern parents suddenly find themselves unable to cope with their over conscientious child, who is stuck in old ideals! They would gladly erase, modify, revoke, yet their earlier image in the child’s mind is stronger than their living voice.) The overseverity with which this reflection in his psyche keeps the original part under constraint, this overseverity, that demands and prohibits, receives then additional support, which only an inner authority can accept. The cruel and deadly hatred that the small infant once aimed at the overpowerful adults is even internalized in the course of his capitulation, and since the child must despair of any resistance, his hatred is turned against his own flagging inner world. For no mobilized strength remains dormant: It rages inwardly as soon as the mind’s eye perceives even an unconscious stirring of drive intensification. It harms us in a thousand possibilities of obvious or concealed self-punishment and self-degradation, illness and inhibition. And if it is not visible in flagrant symptoms, it is at least sensed in what Freud calls the “discontent of civilization,” a malaise shared by us all.

In order to explain this dangerous self-directed sadism of the soul, I have introduced a small piece of psychoanalytical theory, to show in how many different connections such moralistic renderings as Struwelpeter can be called sadistic. For what is expressed as moralistic cruelty against others is merely a reflection of the effects of that internal sadistic impulse. As for the person who “moralizes” against others, we may assume that he presumably keeps his own instinctual impulses calm only by means of heavy fetters. *

Let us look back once more at the humorous picture books that we set aside before. What is the appealing ingredient in the depiction of human nastiness and human misfortune: humor. We can focus on a page in Adamson, the appeal of which to children is well known to you all. Adamson wants to smoke. But his better self, which (identifiable by its angel wings) stands behind him, takes the cigar from his mouth and throws it out the window. For a moment the Adamson self is stunned, but then it races downstairs and catches the cigar before it has reached the ground. Rebellion has acted faster than conscience and the force of gravity. Immoral? Yet the most conscientious person laughs.

“The wonderful thing [about humor] is obviously the victoriously defended invulnerability of the ego. The ego refuses to be offended and forced to suffer by any provocation in reality. It insists on not letting the traumas of the outer world get too close for comfort; indeed, it shows that they are merely an occasion for pleasure” (Freud).

Several external features of the Adamson figure show to what great extent it depicts the child in a human being, the infantile ego, which has to struggle with hindrances, prohibitions, and accidents. In the ratio of his head size to his torso Adamson is a childlike figure; he has a big hat, like a little child acting grownup; he is always alone; he has no manly adventures. And his adversaries, human beings (“the big man”), all are taller than he to the same degree that an adult is taller than a child.

How does humor speak through the depiction of this sly, struggling ego? It confronts the nasty superego with a kindly laugh, which says, “Just look, this is what the world is like, even though it appears dangerous. Child’s play, just good enough to be joked about” (Freud).

We now can look through what is so liberating about these books: For an instant they relieve the ego of the pressure of the superego. Max and Moritz and Adamson are stupidly sly and cruel, as all of us feel we are at some point. But humor smiles at this, and we smile, too. We like ourselves a bit more and perform some tiny detail better than we would have managed without that bright moment.

On the other hand, there is probably nothing that forces us more to sin and do wrong than the constraint of an oversevere conscience. True, the development of the superego may be what shapes our civilization and its powerful characteristics, but the sense of guilt and the need for punishment can go beyond the usefulness of this process. They not only inhibit but can also hinder any improvement on, or restitution of, mistakes. And with the increase today of decent and peaceful ideals and of social awareness, mankind’s heritage of guilt threatens to be renewed in every individual, for it more and more sharply contradicts the primal language of the drives, and with sternness of upbringing, it becomes more and more cruel to the ego. Therefore, human psyches increase both their tension and hypertension. We also notice that all the emancipations (whether sexual, political, or religious) toward which our era is striving fail sooner or later as they are overcome by the discontent in our civilization. They thus become retrogressive, simply repeating earlier patterns. Emancipators are apt to reckon without the superego.

Educators, however, insofar as they are willing to orient themselves psychologically, should certainly not proceed without counting on this factor. Here I call to attention an admirable element in Signora Montessori’s work. We hear about it every day in the House of Children. The equipment surrounding us is arranged in a way that automatically and matter-of-factly points out the child’s mistakes. The teacher is supposed quietly to leave the child who is as yet unable to perform his task alone and, if necessary, simply to supply an easier task. The process of educating the child is made “foolproof,” as it were, by a sympathetic observance of this rule: The two superegos, the teacher’s and the pupil’s, are kept apart while the child’s superego is still labile. A growing severity should preferably not adhere to his very first intellectual efforts. But the question of which strains on the superego formation we can spare the child without weakening the strength of his conscience—that is the problem of psychologically oriented pedagogy.

Montessori’s solution is part of a system based on a rare combination of intuition and science. It is harder for us to draw individual practical conclusions from psychological research. Let us make sure that we are not again overzealous in allowing our lawmaking superego to assert itself. For example, should we simply suppress picture books and fairy tales* without further ado because we consider them dangerous? We can do so, but we should also know that an isolated action can be without significance. A child who is frightened by a picture book has already been disturbed and has merely been waiting for a chance to express it. But this opportunity he has everywhere in today’s world, for anything to be found in fairy tales is also to be found in the air around us. The educator, however, has to know what is happening when the child is unable to tolerate some tendencies in certain books; he should investigate and become familiar with methods of recognizing the prevailing psychological symptoms. He may then refuse to offer books that are in any sense sadistic to an already frightened or easily frightened child. But that is an issue of pedagogic therapy rather than of pedagogy itself.

In order to get at purely pedagogical considerations, we still need one general reflection, with which I would like to conclude. The child pays less attention to the adult’s actions than to the inner tension behind them. Whatever behavior we adopt toward the child, it has less influence than our real impulses—whether or not we have tried to suppress them. Children (like animals) can sniff the real essence through any surface: the cruel of kind, the strong or insecure tendency. If we wish to bring up a child harshly or kindly, suggestively or by merely observing, we must, above all, be able to do so inwardly. That is, it has to correspond to the relationship between our own ego and superego. This relationship is the crux of any effort to create a truly different environment for a child.

The Fate of the Drives in School Compositions (1931)

Foreword

The school essays of adolescents that are discussed here are from the collection of Mrs. Dorothy Burlingham, who founded a little school years ago in Vienna.1 Several times a year she would ask the children to write freely about a given question. For instance: “What do you want to be when you grow up if you had a free choice?”; “How would you like to raise your children?”; or “What would you do if you were suddenly alone in the world (you perhaps had no parents) and had to take care of yourself from now on?” The question did not have to be answered too literally; Mrs. Burlingham (die Schulmutter) explained each time that a story (or fairy tale) was also welcome. Thus encouraged, the children let themselves go and followed their impulses and wishes beyond the confines of a usual school essay.

The answers to the third question, particularly, led us to search for the inner connections between the earlier and later writings of these children and to try to understand their meaning in a psychoanalytic framework. For the third question, for example, a number of children allowed themselves a striking digression: They launched into such a detailed description of their fantasies of their parents’ death that they lost sight of the point of the original question. Twelve children described the death of fifteen parents. Only six of these had died peaceful deaths, three had been murdered; four had died accidentally; two had ended in jail. Thus (as Nietzsche might say), maybe the children chose to write about what they wanted to be free of rather than what they wanted to be free for.

The question obviously arises: Have these children been influenced by psychoanalysis? As it happens, several had undergone a child analysis; others had little idea of psychoanalysis. On the other hand, only a psychoanalyst would notice a difference in the way in which these children handled their fantasies. What the analyst discovers, if he himself has analyzed one of these children, is quite interesting: The unconscious seems to express itself in a such a naïve manner as if it had never been touched by psychoanalysis; however, the symbols the children produce confirm the findings and therapeutic results of psychoanalysis. So we seem to find corroboration of Freud’s afterthought, his remark made at the end of his first (indirect) child analysis (indirect, since the subject being analyzed was an adult recalling childhood)—namely, that the children forgot the analysis just as adults forget their dreams. One can analyze one’s dream at night with the intention of using it consciously on awakening, but “in the morning, dream and analysis are forgotten.”

I. The Bright-Eyed One

A girl of eleven laughs merrily when the theme is given, (question 3) as if to say, “Now I’ll show you!” Then she writes:

Once in spring, I got spring fever. All I wanted was to look out the school window to see whether the sky was still blue and whether the buds had already burst. I was so excited. After school I ran off and let my hair fly behind me. That was so beautifully cooling. At home I gulped my food quickly, pulled on my sandals, no socks at all, and ran out over a lovely green lawn. The bees buzzed, and the butterflies fluttered from one flower to another. I stormed all over the lawn and threw myself on the cool, moist grass. I rolled around and squinted into the sun and did not move for a long time, but I was baked like a pudding. As I lay there, a little rabbit hopped over and wiggled his snub nose. I stretched out my hand and caressed him a bit. Suddenly I saw a horse running as wildly as I had done. So I jumped up and over to the horse and onto his back. And it stormed away. Throughout gallop and gallop, through racing and trot, I sat on the horse, but then I fell down and stretched my arms and legs in the burning spring sun. The bees hummed and buzzed, and the red sun shone through my lids . . . I awakened and looked around me.

Here she notices that she’s gone a bit too far—for a little girl her age. And defiantly she adds in the margin, “That would be the way to get a bit toughened, just what my mother does not allow!” For, as she feels it, it is the prohibitions of Mother that are overridden in this flight into nature, simple commonplace prohibitions—One mustn’t gulp down one’s meal; one mustn’t go without socks and roll in moist grass—but also a less clear and more dangerous taboo: against stroking a rabbit and dreaming of a masterful steed. Illicit in any case; the whole tone rings with the will toward unharnessed feelings and not the will to toughen up, as the girl tries to make the indulgent teacher (and reader) believe.

For the rest we shall note a detail. The first of the impetuously realized wishes is to let her hair fly loose. Now, on another occasion, the teacher heard that the child had had unusually beautiful hair that her mother had shortened. This loss is said to have made an inexplicably profound impression on the young girl; for a long time it was the focus of all resentment against her mother. Can it be accidental that the first event of this rebellion is to let the hair fly loose?

Another time she writes: “I would like to have as many children as possible. They shall not be so swaddled in diapers and covers when they are little. That’s really too hot and sticky.”

And then, with her mother in mind:

Before I have children, I would love to travel crazily: to Italy and Greece, to Egypt, Siberia, and Africa. I would also like to carve wood. I would like to grow very old, so as to see what happens afterward, and then, if I die, I’d like to be told afterward everything that I didn’t know on earth. Then I’d like to return to earth every 1,000 years to visit everything new that has happened. I’d like to have a glass house.

So here is another wish, imagined, like the earlier ones, as limitless: Looking! But here, too, she becomes frightened: “I hope my husband will approve, if not, then woe is me!” For she thinks someone will always fill the role of the no-sayer.

Besides, she wishes to reproduce, not just to look; she wants to carve wood. In fact, the child is highly talented in drawing and painting. Her productions are round and cheerful, like her handwriting and her sentences.

The third time, we hear a little story in answer to the (same third) question of what she would do if she were suddenly on her own:

The story is about a family that’s very well off; they have two cars and riding horses at their disposal. They have a girl, about fourteen years old who was very vain about her long, curly hair. Then came bad luck: The father had an accident, became an invalid, was debt-ridden, drank, and ended in jail. The girl’s first idea was to rush out to the edge of the city to pick many flowers and sell them. While her mother searched for work, she picked flowers, huge bunches, and tied them together with her gorgeous hair. Then she ran back, asking her way again and again, until she arrived exhausted at home. On the next day she tried unsuccessfully to sell the bouquets. Only one man came, asked for a few flowers, and gave two pennies. He told her she had splendid hair and could get a whole lot of money if she sold it. She thought, “That’s a good idea,” and ran across the street to the hairdresser and asked if he wanted her hair. “Oh, what lovely hair you have, but it is dirty. Let me wash it and then I’ll buy it.” She was given a very small sum, with which she ran to her mother, who was so happy and who found her daughter clever and kind.

So the theme of hair has reappeared, in a more weighty form. But we are left to deal with a puzzle: The girl who feels her mother has robbed her of her hair tells a story of a child who sacrifices her hair for her mother’s sake.

A connection can be made between the first and third fantasy, albeit only thematic to begin with, but where does the second one fit? It contains the wish to look as well as the desire to create and reminds us that the girl has outstanding artistic gifts. Seeing the themes of “artist” and “hair” next to each other, however, immediately suggests a somewhat vulgar association. Many artists seem to value their hair and to set themselves clearly apart from other people by their haircuts. We might call it a cult of the self, a kind of narcissism, which they reveal in this way. Following this idea further, we note that it isn’t necessarily the particular acts of personal vanity that document the narcissism of the artist; he has, after all, in his works a grander way of lifting the image of his being to the level of cultural refinement for all to share. And the very charm of a work of art and of the artist himself is undoubtedly attributable to that “self-sufficiency and inaccessability” that Freud saw as the attraction of the child, the animal, and the narcissistic woman, a parcel of sovereignty that does not tolerate any reduction. Still, we know from the lives of artists the setback, the kind of despair into which an artist is driven just when he has expressed his self-love most triumphantly, more triumphantly than his own culturally inhibited soul can bear, given its fear of its own hubris.2

In a long life an artist may experience this polar oscillation repeatedly and give form to this alternating despair and exuberance again and again. But confronted with a short life and a serene, luminous body of work like Raphael’s or Mozart’s, human opinion concludes that the dream of being the darling of beauty can’t last long.

I find this theme in the first fantasies of the young girl, if, of course, on an infantile level: unlimited surrender to one’s feelings and to nature as their soothing complement and then sudden fright. Her fright, however, springs not from the force of Providence, nor is it a pang of conscience that warns from within; no, it is Mother who prevents her from acting on her sensual desires. That Mother cut her hair was the most active example of how she opposes all cravings; it struck at the girl’s strongest wish: to find herself beautiful and to allow others to admire her. If I were to follow our little girl and her problems along this path, which begins with her vehement and vulnerable self-love and then proceeds along many branching trails into the pathological and the musical domains, then I must admit that just this path of the gifted loses itself in dark paths as yet to be illuminated by psychological research, while narcissistic illness is being approached by psychoanalysis with better prospects in view.

About talent, psychoanalysis so far has had little to say. Still, we find some road signs among the works of I. Hermann. He writes in the Zeitschrift für psychoanaytische Pädagogik (this journal), vol. IV, 11–12: “If we direct our attention . . . to the complex of physical beauty and to what in my experience is the necessary spark of the talent for drawing, we find that in many cases the artist was indeed beautiful, especially in childhood. One outstanding painter (a patient) was so beautiful as a child that pregnant women would come to feast their eyes on him.”

Did hair play an important role in the childhood of his patients? Hermann doesn’t say. Therefore, I’ll add the story of a little boy’s fate which seems somewhat analogous to the little girl’s. Unusually beautiful as a child, this boy noticed in particular that people admired his full head of hair. When his mother had it all cut off, he thought he had lost all his charm, and in fact, he did eventually because of all his grieving. Later he became gifted in drawing.