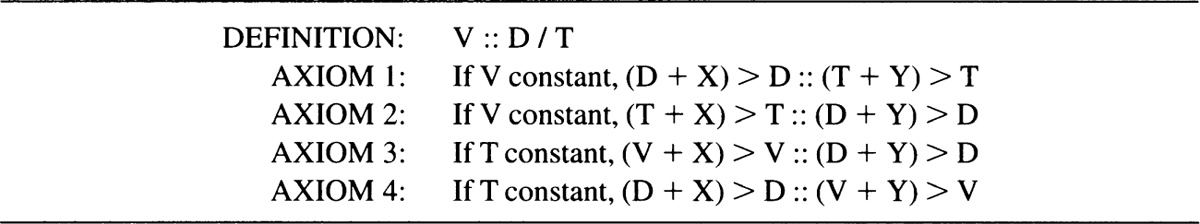

Table 7. Uniform Motion in Galileo: Definition and Axioms.

Galileo, Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences

Part 1 (Third Day: Uniform Motion)

MCKEON: We have spoken about the way in which two authors have written about motion, and we distinguished what Plato and Aristotle meant by motion: their method, their principle, and their interpretation. Today we start our third author. I shall want to start our discussion by asking you a simple question and add this approach to the two preceding varieties, which are totally different. In terms of your previous experience, which is limited to two theories, how would you, in turn, treat Galileo’s conception of motion? I won’t lay down any limit. There’s the brief discussion of what he is going to do on the first page of the Third Day, and then you have six propositions; so that from page 153 to 160 you have a unit.1 Is there anything that you can tell me? Mr. Davis, you can start our discussion off.

DAVIS: Yes. . . . You’ve finished your question?

MCKEON: Yes. [L!] I even told you last time what the question was going to be, so I thought we should start there.2

DAVIS: It seems to me that Galileo is concerned with limiting his concept of motion to more limited classes of phenomena, that is, the . . .

MCKEON: Both Plato and Aristotle talked about local motion, and what are they talking about when they talk about local motion? It’s a limited class of phenomena; it’s actually the same class. What is the difference between the way in which Galileo talks about local motion and the way the others do? . . . Mr. Roth?

ROTH: Well, one of the differences is that the principle in Galileo for motion holds for his particular world.

MCKEON: You don’t think that Plato’s and Aristotle’s do?

ROTH: They hold for their particular world, but they don’t hold through any world.

MCKEON: For local motion, all they are talking about is something like this [McKeon takes a few steps], something like this [he drops a book on the floor], or I could also throw something—I probably shouldn’t—if you want to, you can fill in the blank for me. Those are the only three things they’re talking about. And all three of them are talking about this particular world and any other world you can study in which you can have the forces moving things around. Is there any reference to this particular world in your reading? What particular world would you have to have in order to have a definition of motion you then can find in this Third Day?

ROTH: Any world?

MCKEON: Right, any world. . . . Well, let me go even further. It seems to me that for the purposes we’re talking about here, Galileo is much more abstract than either Plato or Aristotle were. You don’t need any experience about this . . . . Well, let me put it another way—and incidentally, this is the way your answer should have started. We begin with a definition: “By steady or uniform motion, I mean one in which the distances traversed by the moving particle during any equal intervals of time, are themselves equal” [154]. Suppose there weren’t any particles that were moved this way. Would the proposition be thereby falsified? It would be equally true, wouldn’t it? In fact, it’s highly doubtful whether there are any particles that move this way. They would move this way only under very specially controlled laboratory conditions that would be very hard to establish and very expensive. You’d have to control all the variables to achieve this: movement of the wind, the elevation above sea level, the density of the water content of the air, all kinds of things. Why won’t that be our wish? Well, what’s our status? So far we haven’t been told about anything.

FRANKL: Well, I thought Plato began by trying to put down everything that you can know, and Aristotle began from the point of view of that which is already known. Galileo started out by giving a definition.

MCKEON: Well, where’s he starting?

FRANKL: From the point of view of the knower.

MCKEON: This, incidentally, is a good way to begin; that is, among other things, if it won’t work, it will indicate that our analysis ought to be changed. Let’s take our matrix (see fig. 10). What Miss Frankl has suggested—and I’ve made the suggestion before—is that of all the variables which we could handle, the one which we decided was method is the easiest because with method you can take in a whole series of problems. Interpretation is hard because it deals with individual propositions that are true or false. Now, we have said that Plato began with knowledge and moved to the knower. What does that do to motion? Reduce this to two sentences at most; even one will do . . . . Take Aristotle if you feel more comfortable with him. If we know what one method is, then we can ask, What would this other method look like if we identified it correctly? Anyone? What would happen if we begin with knowledge? . . . Yes?

STUDENT: We would want to refer to quality and . . .

MCKEON: Not if you begin with knowledge. No, it was right there from the beginning. It means that if we’re going to analyze motion, we’ve got to find out a model, that is, we’ve got to write an equation which will take in everything; then, motion will be an imitation of this model. And among other things, you will need a cause. Those are the two sentences that I expected. In other words, you would get an inclusive definition determined by the nature of the whole, or the universe, and you can intelligently talk of the cause of that motion.

Let’s take a look at what Aristotle did, his contribution. Since I’ve answered the first one, let me ask you about the second. Mr. Dean? How should I talk about it?

DEAN: Well, you’d start from the known.

MCKEON: In what sense do you begin with the known?

DEAN: You’re confronted by these kinds of motion, kinds of objects, and what the science of them is.

MCKEON: Do you think anyone ever made an induction like that? The knowable is down at the bottom of our matrix. If you were merely going to go out and have yourself a lot of motions and then come up with a science, you’d begin with the knowable, wouldn’t you?

DEAN: Well, I don’t think Aristotle did that because you begin with what is known about motion . . .

MCKEON: All right. What was it that he began with that was known?

DEAN: Nature.

MCKEON: All right. What do we know about nature?

DEAN: That it’s relative to a falling body.

MCKEON: All right. All we needed to know is the difference between internal and external and, as a principle of motion, its cause. Then, what else did we know?

DEAN: We knew it was conditioned with respect to certain categories.

MCKEON: We knew the kinds of motion—you notice, as in the case of Plato, we were committed to what we proposed—and it is significant that we have an external cause. So we got the kinds of motion, and local motion was one of the kinds of motion, just as the local motion that we had from Plato was in part a result of the world soul and in part a result of the lack of equipoise within the world. Therefore, in both cases local motion is down at the bottom. Miss Frankl suggested that Galileo is beginning at the other end from Plato. Would you agree with that first before I . . .

DEAN: That would be the knowable?

MCKEON: No, it’s beginning with the knower.

DEAN: Well, I think he’s beginning with the knowable.

MCKEON: All right, tell me what you would do if you began with the knowable when Miss Frankl thought we were beginning with knower.

DEAN: If you begin with the knowable, I would try to find anything which was a least part that I could talk about and then set up a principle which would . . .

MCKEON: Like atoms?

DEAN: Yes.

MCKEON: Did Galileo do this in the same sense that you’re talking about?

DEAN: Well, no, he didn’t do that. Except that he does talk about a particle moving, which is why I think . . .

MCKEON: But we just said that even if there wasn’t any such particle, this would still be true; that is, for all purposes, it’s doubtful that you could prove it. In fact, at this point it is fictive. Miss Frankl, what would happen if you began with the knower?

FRANKL: Well, first you would set up a frame of reference in which we determine our meaning and . . .

MCKEON: That’s already a fancy term. I don’t know what a frame of reference is. I do know what a picture frame is.

FRANKL: I would get a definition of what I am talking about.

MCKEON: Yes, all of them do that. What kind of definition is this?

FRANKL: I would view a definition in terms of meaningful observations.

MCKEON: Is he?

FRANKL: He says that.

MCKEON: What observations did he make before he says that by uniform motion I mean motion in which the distances and the times are proportionate? Bear in mind, probably in all his life, even after he got through with his inclined plane, he never saw this motion. . . . Any hypothesis?

STUDENT: Well, he’s not really concerned with the truth of his major definition. He formed theorems from his observations, detected errors, and made the definition what it’s supposed to be.

MCKEON: All right, but how does he construct his definition?

STUDENT: What?

MCKEON: How is he constructing his definition? . . . If I were constructing a definition, I might say that by motion I mean the imitation of the eternal object, which is an intelligent animal. I would then be constructing my definition, but I would still only have four possible kinds of motion even at this scale. What’s he making his definition out of? . . . Mr. Davis?

DAVIS: He’s started with three forms of motion.

MCKEON: What determines the forms?

STUDENT: He says very early on he has discovered by experiment some properties . . .

MCKEON: Does he give any evidence of that, or is he pulling the wool over your eyes? What properties has he discovered that are an example? . . . I say that I’m going to define v in terms of space and time, that I’m going to define it so that I will begin with uniform velocity, and that by uniform velocity I mean a velocity such that in equal times equal spaces will be traversed, which means not that every five minutes the same distance will be covered but, rather, that the same space is covered in any time period you pick. This is where I begin. Now, tell me about my past experiments.

STUDENT: It appears he has made observations of motion, of nature, not knowing the . . .

MCKEON: What observations will I have made? Say I’ve lived life thus far in one room, and my food has been brought in, but I’ve read a lot of mathematics and I know what a variable is. Now I write this equation. Do you think I observed it?

STUDENT: Yes.

MCKEON: Well, what observations have I made?

STUDENT: Well, it would depend. I mean, if by setting up an equation you could do it, I guess you could; but in saying “motion,” perhaps you couldn’t.

MCKEON: Why?

STUDENT: Well, I mean, if you only think about it.

MCKEON: All I would need to know is what a variable is. A variable would occur . . .

STUDENT: That’s an equation . . .

MCKEON: All I would need to do is breathe and smell and eat. I would have my pulse; this would give me a rudimentary idea of time. And I dropped things occasionally when the tray came in.

STUDENT: That’s cheating, though.

MCKEON: Oh, no, no. What I’m trying to say is that obviously you cannot get along without some experience . . .

STUDENT: Yes.

MCKEON: . . . but the beginning point that we are making here is not something that would depend upon an experiment in any sense except his ability to write figures on a piece of paper and to draw lines.

STUDENT: Well, what I was suggesting was that he had merely made a rudimentary observation, not doing anything in an experimental way, just testing motion but not knowing how objects fall.

MCKEON: What’s the rudimentary observation I would need? I would need to draw a line, I would need to make points on a line. In fact, that’s all he does. Remember, the second thing we will take up is naturally accelerated motion; but up to that time neither nature is in nor experience is in. You’ve got to have a living experimenter, but the living experimenter isn’t experimenting on himself or basing it on that experience.

STUDENT: What about his distinction between past observations and his experiments?

MCKEON: Remember, we’re not trying to give a life history of Galileo. All that we want to know is what his method was, and what I’m suggesting is that our diagram would give us four possibilities. One would be to begin with the knower. What does that mean? That would mean that you would set up variables in terms of unknowns and you would translate back into concrete knowledge by giving your variables a constant meaning. This would be your method, and you would have confidence that if you got the right variables, you could explain anything that you were ever able to experience.

Let me indicate the reason for making this sort of approach. When we get around to dealing with naturally accelerated motion, he makes the remark on page 160 that if we’re going to talk about naturally accelerated motion, we better do it in terms of figures other than helices and conchoids, though these are very interesting—somebody ought to write a book on them.3 What is he saying here? He is saying that I could in this way take into account all kinds of odd things, such as any spirals I could draw, but it wouldn’t be of much use in naturally accelerated motion. We will, consequently, pick a figure here which is more likely to fit naturally accelerated motion. What figure does he pick? As I say, here we are at the transition where experience comes in. What’s he talk about here?

STUDENT: Parabolas?

MCKEON: What?

STUDENT: Parabolas?

MCKEON: Not for natural motion. . . . Bodies do not fall in parabolas for gravitation.

STUDENT: Spirals?

MCKEON: He asks only one question; namely, since in uniform motion we’re dealing with motion in terms of the time and the distance, if you’re now going to have not uniform velocity but accelerated velocity, there are only two variables: it varies either according to time or according to the space. And he says, I’ve got a bright idea there; I’ve decided that it’s going to vary with the time, not with the space. How does he then prove it to his friends? He proves it by argument; he doesn’t say, let’s go out and drop the two balls. It’s even doubtful whether he ever dropped any cannonballs from the leaning tower of Pisa. But in any case, notice what I’m trying to say about the method. Remember, I said as introduction to him that one of the most influential things that ever happened in physics was the decision to start out just with the d, v, and t and then see where you could go. Add more variables later. Try it on different kinds of motion. Work out the details and elaborate them, and the elaboration would be in terms of more variables. On our diagram, this is beginning with the knower in the sense that you try to find out what the likely variables are or, as he says in this section on naturally accelerated motion, what the figures are we ought to be thinking about if we’re going to deal with this. When you get around to the projectiles, then you bring in the parabola; but the characteristics of the parabola will lead you on the way rather than be something that we draw from instantaneous observations of the successive positions of a cannonball, which would be very difficult even today.

What are the alternatives? Let’s go over them in turn. Notice, if you take this approach, you will build up a series of equations and a series of interpretations. It is equally promising to say, All of these experiences in our background will make sense only when we get them organized in a total whole. We won’t know much about it; we will write it in as simple an equation as possible. As I said, the general field equations of relativity physics are of this sort. Beginning with these, you can then go down and discover that they will have an effect even at the other end. That is, the equations of general relativity affect what we say about particles in quantum physics; but it is by virtue of an interrelation that you have seized upon in your original formulation which, unlike the first approach, does depend upon an adequacy to the universe that you are talking about. If you begin with the known, you split these things into a series of questions and initial distinctions and then, with respect to each, deal with the problems that would lead to further knowledge which is not yet knowledge. If you begin with the knowable, the pattern of inquiry is on the supposition that all that will ever be known will be a more or less adequate representation of a pattern in things. Therefore, you would need some kind of enumeration, such as the early enumeration of the various shapes and masses of the atoms, the later enumeration of the table of elements, and the present series of enumerations of the kinds of particles. Out of these simples, which cannot be analyzed any further, you would build up your complexes and also have other things, like emotions, that would not be built out of these complexes.

STUDENT: In what sense would these simples influence, say, Galileo? I mean, you have to think of elements . . .

MCKEON: No, no, a simple is a thing. Space, time, and velocity are variables; they are not things.

STUDENT: You have to think of the simples, though.

MCKEON: No, you don’t. No, I mean, each one of these three variables are a continuum; consequently, in all of the diagrams we draw lines. We draw lines so that we can divide them indefinitely; the definition of uniform motion depends on that. This is a denial of simples. There are no least parts of the time, there are no least parts of the space, there are no least parts of the motion. It’s entirely possible that if you were dealing with matter you’d have a least part; but you’re not dealing with it here. That would be an entirely different question. For the moment, all we’re worrying about is how you deal with local motion, and in Galileo you don’t need any least part of anything. You do need a way of cutting the line; and, therefore, your particle would be a point—you get a point by cutting a line.

All right, let’s go on. Are there questions about the state of identification of the method? We said it is the operational method; therefore, it would differ very much from the dialectical method, which got us into our cosmology, and very much from the problematic method, which got us into our analysis of time and motion. All right, let’s now take a look at some observations about the definition and the axioms. Mr. Wilcox?

WILCOX: Yes?

MCKEON: Tell me about how we got our definition. How are the axioms related to it?

WILCOX: Wasn’t that question asked earlier?

MCKEON: If it was, it wasn’t answered.

WILCOX: Oh, I thought it was.

MCKEON: How do we get our axioms out of our definition?

WILCOX: Can I answer the first one first?

MCKEON: All right.

WILCOX: Well, once you have his definition accepted, I would think that it’s easy to get the axioms. . . .

MCKEON: Well, those are the parts we’re interested in. The only way in which you can know how to proceed is if you say what it is that you mean. The definition says that, “By steady or uniform motion, I mean one in which the distances . . . ,” and so forth. It’s intelligible. If you want to say what he means, try that.

WILCOX: It’s arbitrary.

MCKEON: All right, it’s an arbitrary definition. It’s an arbitrary definition of some neatness of conception, but you don’t need anything more than to say, This is what I want it to mean. All right, now translate that into the axioms. What’s he mean?

WILCOX: Well, the definition is that distances traveled by moving particles with any equal intervals of time are themselves equal; so if you’re traveling for a longer time, you’ll go a greater distance than if you travel a shorter time.

MCKEON: Well, all right. What you say is what’s in my book, too; but the question is how does what you say relate to the definition of motion?

WILCOX: Well, distance is proportionate to the time.

MCKEON: When?

WILCOX: What?

MCKEON: When?

WILCOX: When it’s dropped. If you travel two different times, they’re related in the same proportion as the distances you traveled in those times.

MCKEON: I took two automobile trips; they were both an hour long. I did 60 miles in the one; I did 30 miles in the other. The distances were different; the times were the same.

STUDENT: But you weren’t traveling uniformly.

MCKEON: I said under what circumstances. Let me indicate what the answers for the first two axioms are, and then I’ll call on someone else for the second two. That is, we have defined uniform velocity. We defined uniform velocity in terms of equal distances in equal times. Taking a look only at this definition, this is what Galileo says: I will derive two axioms. The first axiom says, Let’s keep the velocity uniform. Under these circumstances, if I add an increment to the distance, which makes it bigger than the distance before, then I must add an increment to the time, which makes it bigger than the original time. In other words, with three variables we block out one and ask, What’s the proportion of the other two when that one is held constant? The second axiom is very easy. You do the same thing, except that you turn it backward: the same time, the same distance (see table 7).

STUDENT: Aren’t you adding more when you use the idea of proportions since he says “greater” without bringing in the proportionality? In fact, it seems to me that the theorems are going to turn on the strictness of that point.

MCKEON: No, see, I’ve put a proportion in here. That is, if d + x is bigger than d, then in the same proportion t + y is bigger than t.

STUDENT: But’s that not a mathematical proportion, or at least he doesn’t say the mathematical proportion. He simply uses the undefined word “greater” without saying how much greater.

MCKEON: It doesn’t become more of a proportion when you use equal signs than when you use dialogue. A statement “greater than in the same degree” is a strict proportion.

STUDENT: Well, he doesn’t use “in the same degree,” though. He says x is “greater than” the . . .

MCKEON: Let me read it to you: “In the case of one and the same uniform motion, the distance traversed during a longer interval of time is greater than the distance traversed during a shorter interval of time” [154]. This is the proportion he’s concerned with. Down in the first proposition we will get the specific equality of “greater than.” But to be greater than is not a hazardous relation; it is specifiable, just as we originally began merely with velocity. We didn’t begin by saying “a velocity of a hundred miles an hour”; we said “a uniform velocity.” We said “in any time.” And so, too, the proportion of “greater than” is specified with greater precision as you go along. And each of these, including the original definition, is a proportion.

All right, we have two axioms. What’s our third, Mr. Goren?

GOREN: In the third one, time is held constant.

MCKEON: All right. That is, in the third one we’re going to take time as constant. What’s going to happen to velocity?

GOREN: When velocity is larger or increased, then the distance traversed is greater.

MCKEON: That is, it is like the second in that if you take a velocity plus an increment so that it’s greater than the original velocity, then, with respect to distance, the distance with an increment is greater than the original distance. So you have a second proportion when the time is equal (see table 7). And what’s the fourth one?

GOREN: Again, the time is held constant, and this time the unequal distance is referred to.

MCKEON: I’m not sure what you mean.

GOREN: The speed is such that it will go a longer distance.

MCKEON: Well, how’s that related to the third?

GOREN: Well, he’s talking about distance in the third and speed in the fourth.

MCKEON: That is, keep time constant; and in the third, what is it that varies with the greater velocity?

GOREN: The distance.

MCKEON: The distance is in there, but isn’t distance also in the fourth? . . . The third and the fourth both deal with the proportion of velocities and distances in the same time. How do they differ? . . . Yes?

STUDENT: In the third you change the velocity around and in the fourth you change the distance.

MCKEON: Yes. In other words, for both of them you do exactly the same thing. That is to say, in the first pair of axioms you kept your velocity uniform and then you considered the variability of distance to time or of time to distance. In the second pair, you keep time constant and you consider, first, what happens to the distances if you increase the velocities, then, what happens to the velocities if you increase the distances. In other words, the proportions are in both cases invertible. Notice, if you want something to speculate about, that there would be a third possibility, namely, keeping the distance constant. He doesn’t use that. We will not go into the speculative discussion about why not, but he doesn’t use it for a perfectly good reason that becomes apparent as we go along in our discussion. But in any case, the relation of the axioms to the definition is that they are deduced in the very simple sense that they can be read out of the definition by taking one of the variables, holding it constant, and asking what happens to the other two with respect to it. Therefore, as I said last time, the axioms are deduced from the definition; the definition is arbitrary. Is this all right?

He has six propositions, then. We ought to go along rapidly here. Mr. Flanders? How does the first one go?

FLANDERS: Well, the first part is that the velocity is held constant; then, the ratio of the times is equal to the ratio of the distances.

MCKEON: All right. In other words, our device is something very similar; that is, if we say the velocity is a constant, then the time is proportional to the distance (see table 8). What does the second do?

FLANDERS: In the second, time is constant, and he says the ratio of distances is equal to the ratio of the velocities.

MCKEON: Yes. In other words, we’ll now move time over and the proportion is velocity to distance. What’s the third one?

FLANDERS: Well, in the third one distance is constant and the ratio is of time to velocity.

MCKEON: Yes. And bear in mind, in each case this is a complete proportion. That is, to write it out completely, I would have to say for proposition I, d1 is to d2 as t1 is to t2 (see table 8). But now in proposition III we will hold our distance constant and we will have an ratio of time to velocity. Are there any questions? I mean, we could go through this in some detail, but are there any questions that this is the manner of demonstration through the first three propositions?

All right, we have three more, which are in many respects more interesting. Mr. Henderson? Do you want to tell us what the fourth says?

HENDERSON: It would represent, possibly, the standard form of relating velocity with space and time.

MCKEON: Well, tell us in an nonarbitrary form first. That is, we have been holding one of three variables constant. What are we going to do now?

HENDERSON: You have two multiples, each of which has its own given ratio of time and distance, and the ratios of each one of those multiples, taken as a unit . . .

MCKEON: Well, why are they going to have different ratios of time and distance?

HENDERSON: So that it’s unequal to time.

MCKEON: But now you’re repeating yourself. Why are they going to be unequal to the time?

STUDENT: He’s changing the velocity.

MCKEON: Yes. You see, instead of holding constants now, we’re going to say, Sticking with uniform velocities, what if you have two velocities which are not equal? Isn’t that the condition we’re setting up? All right. Now, if you have two velocities that are not equal, what is it we say in proposition IV?

STUDENT: We say the ratio of unequal velocities is equal to the ratio of the . . .

MCKEON: Well, let me ask my question this way. That is, the reason for combing these variables out this way in the first three propositions, by varying the one we’re going to hold constant, is that we get a different statement about each. We now have three more propositions that we’re going to want to set up. We want to have them with respect to differing velocities, just as our first ones, which are our foundation of what we’re going on, are with respect to constant velocity. In each we will be able to say something about something. What I am now asking is, What do we say about what in each? . . . Yes?

STUDENT: He says that, therefore, that the ratio of distances would equal the speed . . .

MCKEON: We’re making a proposition about the distances in proposition IV. What are we making it about in proposition V?

STUDENT: About time.

MCKEON: About time. What are we doing in proposition VI?

STUDENT: About velocity.

MCKEON: About velocity. In other words, we set up our original definition in terms of three variables, and we’re interested in differences of velocity. Our last three propositions will give us information, in turn, about each one of the variables. With that much as a beginning, Mr. Flanders, tell us briefly what we know about the distances of proposition IV.

FLANDERS: Well, the ratio of the distances equals the alteration of velocities and times.

MCKEON: Yes. Now, if we were stating that not in terms of a proportion but in terms of an equation which has had some importance, what it would look like?

FLANDERS: Well, t1 divided by t2 . . .

MCKEON: NO, leave out the proportion. D equals what?

STUDENT: Well, d equals v2 times . . .

MCKEON: No, vt. Your whole proportion is set up in that way. In other words, you are saying that your first distance is related to the second distance as the velocity times the time in the first instance is related to the velocity times the time in the second instance. Consequently, all the way through you are identifying the distance, the first half of your proportion, with the compound of the velocity times the time. Is Mr. Milstein here?

MILSTEIN: Yes.

MCKEON: What are we doing in the fifth of these propositions, putting it in simple terms? We’re now talking about time and we’re setting up a similar proportion, namely, time is to time, time, is to time2. How?

MILSTEIN: It seems to me that in general terms he gives a general relation from which he could get the following three theorems, theorems IV, V, and VI. That is, dealing with d = vt, you now take two particles’ motion. Then, if you take d1 = v1t1 and d2 = v2t2, the relation of d1 over d2 becomes v1t1 over v2t2. Now you can isolate out your distance, velocity, and time in the equations. What I’m saying is if you’re interested in time, given this relationship, then t1, is v1 . . .

MCKEON: Well, as is the case all the way through, what equation would we be using for time?

MILSTEIN: Time equals distance over the velocity.

MCKEON: Which you could have gotten out of the first equation by a simple algebraic manipulation. What’s the final equation, then?

MILSTEIN: That velocity equals distance over time.

MCKEON: You see, we needed to go through all these steps because we first needed a definition of uniform velocity; then we needed the series of axioms which would give us the variabilities of time and distance relative to each other and the variabilities of distance and velocity relative to each other. Next we needed to consider the situation in which you held constant one of the variables. Finally, we needed to have the comparison of two uniform motions that differ, out of the proportions of which you get a fundamental equation that you can put in any form. In other words, if you wanted a simple statement of what you meant by your original equation, it’s the last proposition; that is, “by uniform motion I mean distance divided by time.” Yes?

STUDENT: Do you get d = vt from theorem IV or do you get it after you’ve gone through everything up to theorem IV?

MCKEON: Theorem IV says d1 is to d2 as v1 times t1 is to v2 times t2. Collapse that proportion into an equation leaving out the subscripts and it is the proposition d = vt. In other words, it’s merely a transformation of exactly the same proportion.

Well, this takes us through the first of the three questions Galileo said that he would ask. The second one has to do with naturally accelerated motion. Let me ask one other question before our discussion is over. I said earlier today in discussing our matrix that when the other two philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, began their method, they needed to have a cause. What does Galileo do with cause? He says, We can postpone that. Notice, we are pretty far in but we haven’t yet come to it. In the operational approach, what a dialectician or a problematic man often mean by a cause is not needed. This is part of the argument about whether there are any causes or not. An operationalist doesn’t need a cause in the sense that the other philosophers need it; conversely, if you make the other two approaches, you need a cause. Therefore, it is not the advance of science which has demonstrated that causes are an unnecessary dynamic; it’s merely the mode of analysis which you choose. We proved that a long time ago.

We will go on next time and read the section on naturally accelerated motion. It is more complex, but I think you can read it in the manner that we’ve been doing; that is, don’t worry too much about the mode of demonstration. There are even some propositions here in which historians like Mach4 argue that Galileo made a mistake. Leave that out; that’s between Mach and Galileo, and it’s still an open question. Try to find out what we are doing with our original material, how the method is going, and, in particular, since this is naturally accelerated motion, how the empirical element now comes in.