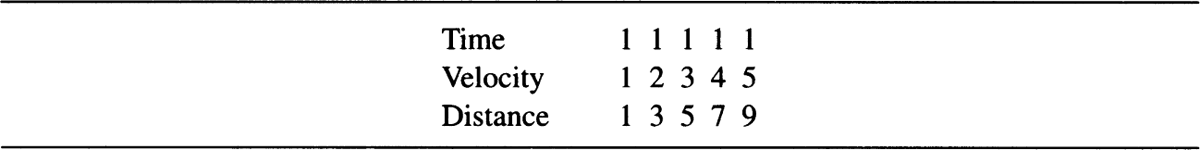

Table 9. Accelerated Motion in Galileo: Time, Velocity, and Distance.

Galileo, Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences

Part 4 (Third Day: Naturally Accelerated Motion)

MCKEON: We interrupted our discussion last time after having plunged into the second set of propositions, taking the first two together, and from there speculated a little about what is going on in these proofs. Now, since we’re interested in the philosophic aspects, I don’t think that there’s any point of going into great detail; but it is important to be able to separate what we conceive to be philosophic aspects of the examination of motion from the nonphilosophic. This is what I want to do now as we finish Galileo up.

Let’s begin, then, with the point at which we left off. I threw out some questions to finish up the corollaries to the second proposition. Is Mr. Davis here?

DAVIS: Yes.

MCKEON: From your observations, what do you conclude concerning these two propositions that we were working on last time?

DAVIS: I don’t think I really made anything of them.

MCKEON: What do we know? How do we know it? How do we set it up? What is it about? What is interesting about it? These are questions of method and of interpretation. . . . Suppose that we begin with the corollaries and work back, then, to the question I initially asked about what’s going on here. The first corollary works out a whole series of conclusions. What are the conclusions about?

DAVIS: The relation of the distances covered to the different times taken.

MCKEON: Is that all he does? . . . That is, if I were to put down a series of numbers—these are enough to begin with (see table 9)—what are they, and how do we know what they are?

DAVIS: Well, they’re the times and distances. We find out that they are related in that sequence through applying the fact that the distance is equal to the square of the times.

MCKEON: No. We need something a little more concrete than that if we’re going to use these to identify something in any instance of uniformly accelerated motion. We will eventually be able to get one from the other—this is the interesting thing—in such a way that from Galileo on it can be alleged you get one from the other either because of experimental or empirical knowledge or because of certain peculiarities. These generate different sequences of numbers, don’t they, mathematically obtained. What’s the second row? . . .

DAVIS: I don’t know.

MCKEON: You mean you’ve reached this point in the University of Chicago without knowing the proper names for this group of numbers?

STUDENT: They’re the natural numbers.

MCKEON: They’re natural numbers. And mathematicians get quite worked up about the natural numbers. One school, for instance, which is very strong on the continent but isn’t as highly esteemed in Anglo-American circles, is called the intuitionists. Do any of you know about the intuitionists in mathematics? . . . Well, let me not lead you too far astray . . . What’s the next set of numbers?

STUDENT: What about accidentals?

MCKEON: No, they’re the odd integers. So, notice, first the repetition of one—it’s a very interesting mathematical sequence. Then you get these natural numbers. Then you get the odd numbers. And it turns out that they’re also the names of what? . . . Look at what Galileo says here.

STUDENT: A series of ratios?

MCKEON: Well, what’s the first one? . . . Obviously, you can’t be surprised unless you can recognize the players and what they’re doing on the field. If you know who they are and they’re doing odd things, then you can be surprised by it.

STUDENT: Well, the first are the intervals of time.

MCKEON: Those are the intervals of time that you can measure off.

STUDENT: Units.

MCKEON: Unit times in dealing with accelerated motion. Remember, we said that this is the operational method; consequently, we do this. This is the first thing we do: we mark off equal intervals of time. If we do that, what’s the second series?

STUDENT: Well, it’s the velocities of the different times involved.

MCKEON: Yes. Those are the velocities. Remember, we’ve been observing as we go along that there are three variables which are all that Galileo needs: time, velocity, and distance. Here, first, are his times. Then, since it’s accelerated motion, the second set are velocities marked off as you take each successive moment of time. What’s the third one? Yes?

STUDENT: Distances.

MCKEON: Distances. And what’s the relation of these distances? . . .

STUDENT: The differences of the squares of the times.

MCKEON: They’re the differences of the squares of the times. Remember, we said that this was the alteration that comes from the t hidden in the v. Do any of you know—remember, he tells you—how he gets the third from the second, in other words, how the reply that was just given is worked out? What is the differences of the squares? . . . The first is the square of 1, which is 1. The second: the square of 2 is 4, minus 1 gives 3—is this perfectly clear so far? The third: the square of 3 is 9, minus 4 gives 5. The next: the square of 4 is 16, and what are we going to subtract from it?

STUDENT: 9.

MCKEON: . . . which gives 7. And so on. The Greeks had been doing this process for a long time. That is, there are a whole series of mathematical and physical relations which can be set up by a process of approximating a number which exceeds or is less than a given amount, that is, by a process of adding and subtracting. The point that I’m trying to make, and what is important here, is, you notice, that what we have been doing involves the discovery of very unique relations that are in arithmetic and nothing more than arithmetic—no lofty mathematics are involved; analytic geometry has not yet been discovered, nor has differential calculus—and yet this corresponds very nicely to the subject matter that we are investigating. Our method is precisely to find relations that we can do this with. This is our first step of generalization.

Let’s go back, then. I want to do two things. Mr. Davis, how did we tie this business of accelerated motion into our motion? We did it in the first proposition.

DAVIS: By saying the spaces are equal when, during the same time, a body moves at uniform acceleration and when it moves in uniform motion at half the final accelerated velocity of the first.

MCKEON: Since this is uniform motion, it’s relatively simple to relate a motion which increases uniformly with a motion which is uniform, particularly since the only things that we need to notice are the time and the distance. Did you notice, Mr. Davis, what’s happened? Remember, we said that one of the peculiarities of this geometric proof is in what it is that is represented. Are we doing anything strange in theorem I?—Let me take back “strange.”—In the figures for the first six propositions, what do the figures serve to do? That is, what do our lines represent?

DAVIS: They represent variables.

MCKEON: Don’t be fancy. Tell me what the variables are.

DAVIS: I think they represent time and velocity.

MCKEON: Time and velocity. In other words, you can draw a straight line to represent any one of these three: a straight line which represents time, a straight line which represents distance, a straight line which represents velocity. And we began just by drawing lines of time and space. That’s all we needed for the first two propositions. Then we got another line going, which is velocity. But all the way through, all we did in our lines was to draw them, look at them, and indicate what happens to the variations. We get into triangles now. It’s the triangle I want you to describe, on page 173. . . . Is Mr. Clinton here? . . . I better get out the authentic class list, the old-fashioned one.1 Is Mr. Rogers here? . . . You can have the same defects in both; technological civilization and manuscript civilization are the same. [L!] Mr. Roth?

ROTH: Here. You want to know what the difference is between using the lines and using triangles?

MCKEON: And I don’t mean anything fancy, just a simple answer.

ROTH: You’re asking about the perpendicular lines?

MCKEON: Look at Galileo’s figure 47 on page 173. The whole purpose of the picture is to demonstrate the equivalence of a rectangle to a triangle by a simple Euclidean demonstration which discovers the equality of two triangles, one of which you slice off the first, large triangle and place it up on the top to get yourself a rectangle. It is the horizontal which is velocity. Consequently, what we are doing here is constructing a means of demonstration to carry us over from the uniform motions, which the rectangle would represent—that’s why we didn’t need any triangles before as we went along—, to the triangle, which is what we’re interested in now because we’re going to come along with velocity increasing and acceleration coming in. Isn’t that correct? If that is the case, then, going over to the next page, we try to put this down in a form in which we can relate the time-velocity relation to different spaces. You’ll notice, time and velocity are together in figure 47 [173], and we put our space outside on the side where it really does not enter directly into the picture—CD is space. We do the same thing over in figure 48 [174]; but we are now trying to relate them, and we say it first arbitrarily. We break our space into proportions which we are going to relate to the proportions which our triangle establishes between the time and the velocity. Then, our corollary states what this is. It also indicates that we can’t represent the direct variation by a simple geometric figure; that’s why space comes in a little curiously. This is all we have to it. As I say, we’re not doing an elementary course in physics or mathematics. What I want to know from this is, Mr. Roth, what Sagredo is doing on page 176 Yes?

STUDENT: Well, he’s doing just that. He’s got a figure which does relate time in a way that includes the distance.

MCKEON: Well, let me ask the question this way. Is there any defect to this? Would Salviati be delighted by this? Does this indicate anything which, when Sagredo is going along doing great, you would be able to recognize as his normal procedure?

STUDENT: Well, the previous example would be using the pendulum, while Sagredo would know . . .

MCKEON: No, no, no. The pendulum itself was Salviati’s. Sagredo didn’t use it before.

STUDENT: Oh, yes. He would say that there was something similar to what this device would illustrate. For instance, in the case of a pendulum you have an example of what the effect would be in terms of something that could be apparent, and here again which was . . .

MCKEON: Well, as I say, in some respects this is an easy question, in some respects it’s a hard question. What figure 49 [176] is doing—this is all that I was driving at—is reducing what Galileo and Salviati have been saying about uniformly accelerated motion back to uniform motion. The figure is, in other words, a kind of sanctification of what we’ve stated. Consequently, Salviati eventually will say, in effect, Of course, it was very nice, very elegant, it nails it all down; but you don’t get anywhere with it. In other words . . . Well, as I say, let’s not generalize too soon. I want by the end of this discussion to get our three speakers related to each other in a way which would make some sense.

On page 178, then, Miss Frankl, Simplicio enters into the discussion in this sequence; and this is where we may begin to separate the characters of our drama. What does Simplicio say about the demonstration? What does he want?

FRANKL: Application.

MCKEON: He likes Sagredo better than he likes Galileo. He thinks that it’s elegant, it’s clear and simple, and that Galileo is obscure. He’s going to go on and say that he’s not satisfied: he’d like to know, apart from the nicety of the demonstration, whether this is the way bodies fall. In other words, you’ve now got three interests. Could you restate for me what it is that would make him think that Sagredo is clearer and Galileo more obscure, particularly in a form which would lead to their differences? . . . Let me come back once more to what Galileo has managed to do. He got us this series of very interesting sequences of number which permit us to separate out our variables: time, velocity, distance. What Sagredo has done has been to say, Well, in effect, we really haven’t contradicted anything that we said before; we’re back where we were on uniform motion, and that’s all perfectly solid, sound. So they’re not arguing about the conclusions. What would be the difference between the two? Yes?

STUDENT: Galileo is working with determinants, in fact, numbers; whereas Sagredo is using a theoretical representation, which is closer to what Simplicio wants to make determinant.

MCKEON: I think you’re headed in the right direction, but you’re putting it in ways that might be subject to dispute. You see, Sagredo already comes out worse because he’s just making his representations. If what we’ve said is correct, they’re all using the operational method, and the operational method is given. For example, they have no objection to representing velocity as a straight line. This would be pretty far from a logistic method where you would want to keep your various lines in your analysis distinct. You are representing all of them by straight lines; consequently, it’s either the dialectical or operational method, and here it’s more operational than dialectical. If this is the case, then maybe their principles are different or maybe their interpretations. In other words, if their methods, as far as we can tell, are the same, what would be the difference between them? . . . What’s Salviati’s principle?

STUDENT: To determine the causes?

MCKEON: Well, forget them for the moment. If the dialogue is looked at in terms of what each one is pushing, what is it in terms of his principle that Salviati needs to explore more of? . . . What’s the name connected with it? . . . Momentum, inertia, impeto: that’s what has permitted him to make the distinction that he made. And Sagredo has no objection to momentum or impeto. But what is it, if he is dealing with it, that would be different? How would the two differ? . . . Well, let’s push on from this because I think that as we go along we may have more evidence. This is the kind of distinction that I think would be of importance.

We have now reached the point where we’re making the transition from page 179 to 180. Like two scientists, Salviati has approved of Simplicio’s question. It’s a reasonable request and the necessary reply: mathematical demonstration of the natural events. And by the way, here again there is an indication of what the peculiarity is of method that we are dealing with. Did any of you notice what the examples were of the application of mathematics to natural events? Let me read it to you, and then you tell me. On page 178 Salviati says, “The request which you, as a man of science, make, is a very reasonable one; for this is the custom—and properly so—in those sciences where mathematical demonstrations are applied to natural phenomena, as is seen in the case of perspective, astronomy, mechanics, music, and others where the principles, once established by well-chosen experiments, become the foundations of the entire superstructure.” Notice, it ranges from pure sciences like astronomy to applied sciences like mechanics, perspective, which would run into the art of painting, and music, which could be the scientific analysis of the basis of composition. This is a universal method, that is, an operational method which would apply in all subject matters; and, therefore, Salviati is taking advantage of it. Consequently, we’re going to discuss this at length, and the author has opened up the door. This is where he describes the experiment of the ball rolling down the inclined planes with the spaces as the squares of the times. The inclinations are different, and the times are measured by water collected in a glass and weighed as a result. And Simplicio is delighted.

Salviati continues, then, to corollary II, which has a scholium that starts us going in our direction. Here, again, corollary II is something you can understand easily on one level, but you might have difficulty on another. On the easy level, Miss Frankl, where do we get in corollary II?

FRANKL: You get a connection between time and distance.

MCKEON: Do the rest of you agree with that? . . . You shouldn’t. . . . Miss Marovski.

MAROVSKI: Well, he begins by taking two distances . . .

MCKEON: I know, but where have we gotten them? What you’ve said is correct, but now underline it. Where have we gotten it underlined before?

MAROVSKI: The times are related to the distances . . .

MCKEON: Is that all that you think is going on? . . . Remember, his trick all the way through has been to hold a variable constant and then do something hairy. What’s he going to hold constant? Back to you, then, Miss Marovski.

MAROVSKI: He’s talking about different distances covered in different times.

MCKEON: Any old time?

MAROVSKI: Any time.

MCKEON: Yes. Consequently, we’re going to forget about the times. What are we going to try to compare?

MAROVSKI: The distances.

MCKEON: All right, distances, but then what?

MAROVSKI: They’re proportional to the times?

STUDENT: In terms of a distance that can only be compared with another? . . .

MCKEON: Well, let me ask this question. Figure 50 [180] is only one line. What’s the line represent? . . . Only distance. You’re going to compare one distance with another distance by a mean proportion of the two distances. Therefore, I would have thought on this simple level it was easy. What I am saying would, in more subtle terms, have difficulty, but on this simple level he has established a way of setting up the proportion in terms of distances, keeping the other variables fixed. Yes?

STUDENT: But you do have any time intervals, so you have the square root of the times. That is, you have more than one time involved.

MCKEON: Anything you say about the proportion of the distances can be translated back into the times because the times and the distances vary together. But we’re trying to write an equation in which we get time in terms of distance. It involves a translation into velocities or times, if you wish; but having said that, why would this be important here? . . . What’s the difference between a body falling from a point and rolling down planes of various inclinations? . . . Only the distance they go through. One of the things we’re going to try to show is that the velocity at the bottom is going to be the same, and, therefore, the momentum is going to be the same. The inclined plane will be of different lengths, but the perpendicular distance will be the same. Therefore, we need a means of comparing them which will keep our distances without intrusion of anything else.

Well, this is corollary II. We then go into the scholium, where he takes up the case of the vertical fall and the fall on inclined planes. He says he is pausing to add a better confirmation of the principle by means of plausible arguments and experiments. Mr. Henderson?

HENDERSON: Yes.

MCKEON: What is the principle, why does he want to examine it further, and what ought he to do?

HENDERSON: He gets . . .

MCKEON: He’s going to establish a single lemma, he says. We need to focus on the lemma.

HENDERSON: I took this to be negative, that he finds the same relation between changing the acceleration, which becomes dependent upon the incline, and the resulting velocity, which would change per unit time over the incline.

MCKEON: Yes, but what about the final velocity?

HENDERSON: That they’re proportional to the distances.

MCKEON: Suppose that I’m rolling a ball down a plane and dropping one from an equal height. The final velocities, the final momenta, are going to be the same.

STUDENT: I think he shows that the point of equilibrium is achieved in the one case, well, because of the question of differences in weight. He shows that in one case, if your weight on the incline is less than the weight on the vertical plane, that you have an equivalence to the same . . .

MCKEON: No, no, no. I think you’re coming around to a different question, the question of what momentum a thing has whether it’s on a plane or on a flat surface. No, that would not enter here.

STUDENT: Well, what I was trying to say was that from this point . . .

MCKEON: You see, among other things, you can’t get him proving that things will fall faster if they’re heavier because if you did, you would have made a mistake.

STUDENT: No. What I’m trying to say is that this seems to suggest that if we had equal weights, the distances would be equalized because of what . . .

MCKEON: Do any of you think that Salviati’s going this direction?

STUDENT: It would be equalized because . . .

MCKEON: The only statement he makes is about the inclination of the plane. He says nothing about changing the weights of the bodies.

STUDENT: Well, my question was that it would destroy distances with the vertical fall, but he wants to show that the velocities are going to be the same and the velocities are going . . .

MCKEON: Look. I said it before; it’s a very simple point. Suppose you have an inclined plane AB with the points F and G equidistant from the horizontal AC (see fig. 21).2 It is obviously the case that there are two questions you can ask. It goes back to what we said in the beginning that he says is the most important point, namely, that the variation in your uniform motion will be such that in any time, equal spaces will be traversed. It’s that any which is involved here. Suppose you ask one question: What will the velocities be at G and F of two balls starting from B, one falling freely and the other rolling down AB? You have one answer. We know in advance, since we’ve read it, that they would be the same. Suppose you then say, What would be the velocities after each has gone three feet more? You then have them at I and at H. Will the velocities be the same? No. You’ll notice, I’ve deliberately taken distance: they don’t vary as the distance.

Consequently, he wants in this experiment to examine two things: one, that if you drop a ball—and it’s not a heavy or a light ball, the same ball or a different ball; it doesn’t matter—and if it falls freely, the acceleration will be faster. But if you drop the ball along BC or roll it along the plane AB, when it gets down, the final acceleration will be the same either way. And it is the desire to keep these two separate that makes the experiment important. It’s important because what we are interested in is the free-falling body, that is, in natural acceleration. That is very difficult to measure unless you slow it down, and you slow it down by an inclined plane so you can measure it. You want, then, to know what it is that you can carry over as the same between the two cases, and it turns out that it is the initial and the final stages, nothing in between. The accelerations will be different: the accelerations will be proportionate to functions which you give them, to the lengths of the incline. The final acceleration, however, will be proportionate to the perpendicular height, also a line. Notice, our triangle’s in there, but the horizontal that we are working with should come out a velocity as we go along.

Let us now speed up a little because, you recall, what I wanted to get was the differences between the positions of the three speakers. I don’t think you can get them in the usual way. It is usually alleged that Simplicio is an Aristotelian, an Aristotelian only because he was wrong about some things and all the errors in Galileo’s time were Aristotelian. If it is true, we need further characterization to show it. But one of the things that I asked in my question was, What is the lemma we want which would deal with a relation of the impelling forces? He says very definitely what the reason is we want it: he wants to be able to conclude geometrically from it; he wants to put it all in a geometric form. This all turns on the nature of the momentum. Notice on page 181: “Therefore, the impetus, ability, energy, or, one might say, the momentum of descent of the moving body is diminished by the plane upon which it is supported and along which it rolls.” In other words, the lemma that he’s introduced is the lemma about the inclined plane. And you’ll notice, it’s totally independent of what he wants to prove; namely, what he wants to prove is something about the final state, whatever the plane or the perpendicular that is involved. It is for this reason that the impetus, the ability, the energy assumes a place of some importance, one that I suggested would be properly called a principle. In fact, he sometimes calls it a principle; although he doesn’t use the term with great precision, in several of his instances it’s the same as what we mean by it.

On page 182, he demonstrates this by a consideration of the origin and nature of the instrument of the screw. Do you remember when I was asking you what a helix was? The screw is in here; it begins in a posterior place. He’s quite right that what he wants is the variation of time, distance, and velocity; and then we talk about the screw. We don’t begin with a helix, which is a highly complicated thing—here, again, I’m rushing because I want to finish Galileo today. Remember, when we were talking about the pendulum experiment, we tried to show the reason why you needed the pendulum: it was premature to bring in the inclined plane.3 Now, on page 182, he is saying that the impetus in the descent of a body is equal to the resistance of the minimum force necessary to prohibit the motion and to stop it. In other words, this is a formulation in straight lines that your pendulum gave you automatically in curves; and he is ready now to formulate it. Sagredo then generalizes again: the momentum of the same body along differently inclined planes is inversely proportionate to the length of the plane [183]. That is, notice, once more he has great generality. The peculiar importance of the momentum that Galileo is pushing at is given its proper mathematical place.

Salviati then goes on to demonstrate his theorem. It is that the rate of the velocity of a body descending from the same height along differently inclined planes is always equal on arrival at the horizontal if all the impediments have been removed. Notice, again, the relation to the lemma; that is, the lemma carefully first gave you the differences in the descents along the various planes. Now you get your theorem. He then goes on to a series of variations that I would like to go into, but we have to leave them for the moment. Theorem III and its corollary: the times of descent are relative to the lengths of the plane. Theorem IV: again, the times relative to the inverse ratio of the square roots of the height. Theorems V and VI go on in much the same way, and the corollaries to theorem VI give you once more a sorting out of our three variables.

It is at this point—and I want to spend the last few minutes on this—that Sagredo comes in again with another idea. We’re now at page 192. It’s an observation about “a freakish and interesting circumstance, such as often occurs in nature and in the realm of necessary consequences.” If lines from any fixed point are drawn on a horizontal plane, then you can get ripples—but, notice, the point is on a horizontal. He then distinguishes two kinds of motion in nature, the uniform and the uniformly accelerated, and gets two kinds of circles, the concentric and the eccentric, where the latter deals with the origin of an infinite number of centers and one point of contact, a highest point. On page 193, after all of this, Salviati says, “The idea is really beautiful and worthy of the clever mind of Sagredo.” Simplicio comes in and says that “there may be some great mystery hidden in these . . . results” which is “related to the creation of the universe (which is . . . spherical in shape)” and “the seat of the first cause” [194]. Salviati says he agrees with that, too, but that “belong[s] to a higher science.” Having summarized these on the supposition that the three men are using the same method in this discussion, what is the difference between them? What’s the higher science Salviati refers to? . . . Yes?

STUDENT: Metaphysics?

MCKEON: It’s theology. Theology is sometimes called metaphysics, but Christian theology is a little different than most forms of metaphysics. What kind of a principle would Simplicio deal in where he wouldn’t object to Sagredo’s statement? . . . Comprehensive principle. You remember that there would be nothing wrong with this. And that’s why Salviati says, Sure, we could do this if we had time, but we’d get into a lot of other questions. As opposed to a comprehensive principle, what is it that Sagredo represents? . . . Yes?

STUDENT: A reflexive principle?

MCKEON: No. A reflexive principle would identify the thing at particular times and in particular modes and would go along on that basis. Notice, what he’s been doing, on the contrary, is that every time Salviati gets some momentum going, he says, Oh, yes, I could show you where he gets this. Then we go through a little proof in which the momentum practically disappears.

STUDENT: Actional?

MCKEON: It’s an actional principle. That is, it’s perfectly good mathematics; there’s nothing wrong with it, except that the physical aspect disappears. And that leaves Salviati. What’s he have?

STUDENT: Simple?

MCKEON: If it were a simple principle, then you’d have to be able to identify it in other ways, such as an atom. That leaves only a plain choice, but maybe he’s fairly safe working on the prejudices that come in. Yes?

STUDENT: Reflexive?

MCKEON: Well, why is it reflexive? I mean, let’s . . .

STUDENT: He’s going to talk all about one particle and each . . .

MCKEON: No. Just stick with what we have here. That is, we’re talking about particles in motion: therefore, it might look as though it was simple. But how are we going to identify the motion? What does momentum mean? What is the . . . yes?

STUDENT: Well, he’s talking about the particles in a particular state and . . .

MCKEON: Yes.

STUDENT: . . . at a particular time . . .

MCKEON: In other words, the momentum it has is the motion it has and the motion it will have. Consequently, as a principle, the identification of the particle by its momentum gives you all the characteristics that you need in order to deal with it as part of a moving system. It is reflexive because the momentum is what moves it, and it moves it because it is moving.

Well, we come to this base with too much of a slide. Don’t take this as a necessary solution; take it, rather, as an illustration of the way in which the argument might very well have been set up. That is, if what Galileo is attempting to show is the importance of a new approach, he wouldn’t want to do a large job of refuting all other philosophers. In all probability he would not be anti-Aristotelian in any simple sense; he’d leave that job for another fellow. But suppose you concentrate all your attention not on a group of people who would pay attention to this kind of debate and, consequently, would all need to be within its limits, but on one where they would all need to agree in the discussion with the mode of analysis being attempted insofar as operational; and, then, consider the interrelations that would be causative of the principles, pushing hard toward the need to consider the whole question in terms of those determinations which at any given moment are the source of the motion of the particle. It’s this that governs the discussion of the particle when it is on a plane: if it’s on a plane, it has to have momentum. It has momentum when it is not held back; and, therefore, this is pre-Newtonian, pre-Leibnizian. Our only consideration will be the particle as moving or not moving.

For next time, I think we ought to go on to Newton because our purpose is not to make you experts in Galileo’s thought nor, again, in Plato or Aristotle. The book I’ve suggested is the Hafner Newton’s Philosophy of Nature. Don’t read the Introduction; I usually say that—I mean, you can; all I meant was don’t be too influenced by it. The same thing goes for the section on “The Method of Natural Philosophy.” The “Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy” come later in the Principia, where they are treated with some care. Begin on page 9, which is Newton’s Preface to the First Edition. Read that and then go on to the definitions and the scholium from Book I. Running all the way through that will carry you from page 9 to page 25, where you get the axioms, or Laws of Motion. This is to say that you ought to have read and meditated this much by our next discussion. Read more if you have time.