Table 10. Modes of Thought: Principle, Method, and Interpretation.

Motion: Selection

In the last lecture I dealt with the third aspect of motion and the related aspect of space. We have now considered the parts of the meaning which could be attributed to method, principle, and interpretation. Then, in the final part of the lecture I started to explain the ways in which Plato, Aristotle, Democritus, and the Sophists would differ in their analysis. I won’t resume the example now, though I will do that from time to time, because I want to go on to the one remaining variable in the definition of motion, that is, selection. Bear in mind, as I’ve pointed out repeatedly, what we are trying to determine is not the question of what motion, time, space, and cause are in the sense that you would determine what a tadpole is or what an artificial object like a table is. Of these four concepts, the only one that we experience directly is motion or change, and we have seen that in dealing with motion or change you can work the related ideas as a kind of accordion. You can either deal with a minimum kind of motion and then explain all the other motions in terms of that; or you can deal with the larger concept of change, of which local motion is merely one variety. Therefore, in the nature of things, there is nothing wrong with the supposition that you can do the whole job in either direction. If this is the case—and one can determine whether or not it is by examining the history of science, the history of philosophy—if it is the case that all of these ideas have fruitful interrelation in the development of our sciences based on motion, then it is worthwhile to examine what the meanings of motion would be.

We have tried to get hold of these conditions of variability by recognizing that, obviously, the only way in which we can take account of motion is to take account of motion. Motion is out there, but motion will not think itself: we think motion. Therefore, the beginning point of anything that we would say about motion is in the process of saying, which involves not merely what we’re talking about, the object in motion, but also the knower, also something which underlies this process in the nature of things, and also something which systematizes. We’ve called these four variables the known, which is the motion that we report about; the knower, which is the first in the process of investigation, of talking about the motion; the knowable, which would be the things there that we infer from the total situation would be relevant to what is going on; and the knowledge, that is, the systematic schematism, which can take on highly bizarre forms such as the world of ideas of Plato, or can settle down to a more workable, more comfortable twentieth-century form by becoming a set of equations—though it amounts to much the same in either case.

If this is so—and this is where selection would come in—, then it’s obvious that our machinery of analysis is involved in the same changes: those are changes you analyze. In other words, what we will mean by the known, what we will mean by the knower, what we will mean by the underlying knowable that is not yet translated into the known, or what we will mean by the knowledge which is the systematization that exists or will exist when we get beyond what the scientist romantically calls the frontiers of knowledge, all of this will vary as our analysis proceeds. In the schematism, consequently, we have relied on the fact that a schematism can be set up in neutral terms by merely taking account of the variable which you will identify later. Then, given these terms, any statement which is true or false involves a minimum of two terms—any larger number can be reduced to two—; an argument or a method involves a minimum of three terms—larger numbers are reducible to the three—; and principles will organize a system, or n terms. In this process we are also engaged in picking both our vocabulary and our world of experience. Let me recall to you what I said in the first lecture. I shall want any statement that I make about language to be translatable into a substantive statement concerning what the language is about; conversely, any statement that I make about a subject matter can obviously have its characteristics traced to the language. Therefore, for all of these terms there will be both a substantive and a formal aspect, and they should go together not because of anything in the nature of things but because I’ve set the analysis up this way.

If this is the case, there is an infinitely rich vocabulary which we could appeal to and out of which, in any actual statement, we make a finite selection: this is the meaning of the word. In any small experience, in looking at the surface of a desk, for example, there is a potentially infinite number of characteristics that could be observed. It doesn’t require a great deal of ingenuity to see what a research project it would be in order to go on endlessly observing things that could be said truly about the desk top. It would be a happy life, in fact: you’d know exactly what you’re doing all the time, and there’s no end to what you could do. But out of that infinite possibility in any experience, a rich one, we make a finite selection. Normally, we don’t do it deliberately; it’s done for us by the processes that we engage in. It’s done for us sometimes, when we’re original, by something we decide to do. But when we’re not original, it’s done for us by the methods we have learned, the language we speak, the culture we are part of, the habits, the prejudices we’ve gotten: all of this picks out our vocabulary. For the purposes of philosophy, this selection of a finite vocabulary or a finite dimension of experience gives us means of determining what we consider to be the real problems, the meaningful statements, the entities that we will consider real, the kinds of structures that are relevant or important or true or meaningful or fruitful: these are all words that we would use. But the purpose of the selection, once one observes it, is this. Consequently, it is the selection which determines the problems in an individual philosophy, and it is also the selection which determines the meanings that are shared when men argue. In talking about selection, then, I shall want to deal with both: that is to say, I will deal with, first, what happens to philosophic vocabulary or the world of experience when you take a position; second, what happens to the philosophic vocabulary when opposed positions come into play, because the opposed positions are the fashions of the epoch which will permit even an existentialist to talk with an analytical philosopher or a pragmatist to talk with a dialectician.

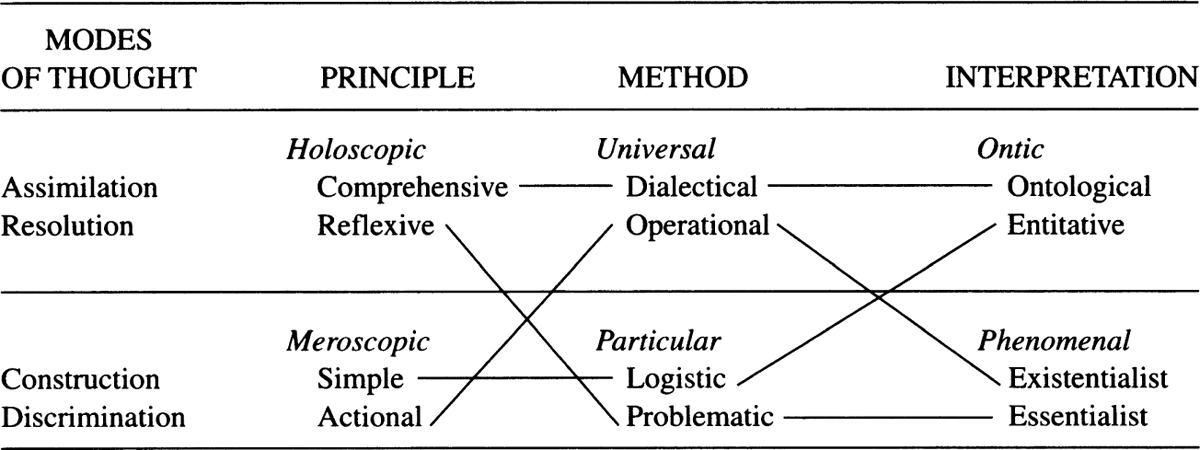

Let’s begin, then, with the selection that you make in a philosophy, and let me do it by bringing out an aspect of the structure that I’ve not talked about before. Whenever I set down these positions, you may have observed that I divided them in pairs. The principles, for instance, were holoscopic or meroscopic. Under the holoscopic principles we had comprehensive principles or reflexive principles. Under the meroscopic we had simple principles or actional principles (see table 10). There are two arguments that are going on in any age in philosophy. One is the argument within each family between the various positions. Bear in mind, these are all large terms: there are more than one kind of comprehensive principles going on at a time, more than one kind of reflexive principles. In these arguments within the family, the holoscopic principles will have some shared meanings, but differences; the meroscopic, some shared meanings, but differences. The arguments between the meroscopic and the holoscopic, however, are the violent ones; and in all ages there is one group of philosophers that calls the whole enterprise of the other group meaningless, nonsense, full of unreal problems. These are the arguments that go across this main division.

Look back at the matrix in figure 12, and we’ll see whether what we know will explain this selection. The diagram itself gives you some reason for the diremption and some reason why there are two. Members of the family of meroscopic principles speak to each other, they’re merely going in opposite directions on the same street; and the two members of the holoscopic family do the same thing. A principle may be an attempt to relate knowledge to the known. Bear in mind here the meaning that we have given these terms. Known is any knowledge that has already been found out. All the knowledge which is in books is instances of the known. Knowledge is the structure which makes the known knowledge and, therefore, it would extend beyond. Normally, when you make your beginning with knowledge, you make your appeal to some transcendental aspect, something which would never be exemplified fully in any individual instance or any number of individual instances.

The difference in the direction is extremely important. Suppose we begin with the known, and again, for purposes of convenience, I’ll take one of the ancients, Aristotle. Judged by the amount of time that he spends thinking up arguments to refute it, the one thing that irritated him more than anything else is the separated ideas of Plato. He gives a long list of arguments against them in the first book of the Metaphysics; then he devotes half of the next-to-the-last book and part of the last book to another series of arguments. In other words, what he is saying is that the beginning point would have to be within a restricted body of knowledge already possessed, and to suppose that there is something out there beyond it which exists apart—the Greek word is much more explosive: Xoristan—is just nonsense. By means of these principles, you can make a progress which will reduce things not yet known to knowledge; but the important thing is that you begin with what is known, and those things have principles. That is, you know what the causes are within any branch of knowledge: the causes which make the knowledge possible are reflexive. This is why it is a reflexive principle. Nature, for example, is an internal principle of motion. Therefore, you can separate physics from the practical sciences and from the poetic sciences; even within physics you can separate the different parts of physics, depending on the cause which you have found that you can extend to other inquiry in the investigation. For Plato, you begin at the other end. That is to say, none of the known would be possible unless it was part of an already intelligible, intelligent whole. Note, we have a cause again, but here the cause is the intelligent maker who made an intelligent animal imitating this principle of intelligibility. The basic intelligibility of the organic whole will lie behind anything you seek to know about the parts, in the event that you wanted the parts. Starting with the known, Aristotle will want to go on to wholes, even having a cosmology; but cosmology is not the prerequisite of the examination of motion on earth, whereas for Plato it is.

Notice, that if this is what we are talking about, they’re in total opposition to the meroscopic principles. Bear in mind, the word principle, in case you’ve forgotten, principium, means “beginning,” a “start”; and you can have a beginning in two senses: the formal beginning in the sense of the principle of knowledge and the substantive beginning in the sense of the cause of the process. For the holoscopic principles there is an identifiable cause other than motion; for the meroscopic principles there is no cause other than motion—notice, a literal beginning. Suppose we began with the knower and cut off the knowable. A perfectly good case can be made that if I am dealing with any process, I really don’t know what the process is until I can produce it. If I can produce it, I know it. I don’t then have to say that since I can produce it and have a statement of the method of producing it, it is, therefore, produced in nature this way. Many of the models of the atom, for example, are models that could be constructed in gross form; but speculators at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century frequently say, Look, when we take a cosmological model and say it is like the planets going around the sun, we don’t mean this. What we mean is that there are certain aspects of the phenomena that can be accounted for by supposing this planetary model. If, therefore, in our imagination or—to come down from this into more manageable dimensions—in our laboratory we can make the thing that we’re talking about, then we know it. That’s a beginning. The other approach is just the opposite: simple principles. Suppose I wanted to explain something and I explained it by constructing it. If I looked at what it was that I was using in the construction, then any time that this was itself constructible I would have to account for it. But whenever I got back to something which was simple, which had no parts—there are many different criteria of being simple; the atom is just one variety of this simple—then, if it was simple and had no parts, I wouldn’t have to account for it, I’d have a beginning. That is the principle; and if out of this principle, out of this beginning, I can construct the more elaborate structure that I’m talking about, everything is accounted for.

What is the cause of motion? Well, in the one case it is the motion which the experimenter either produces or imagines—notice, he doesn’t have to perform the experiment; for many of the models which he uses he couldn’t. In the other case, it is the motion that already exists in the simple. The cause of motion, then, is motion; and questioning whether or not there is anything such as a cause apart from the process itself is not an invention of the twentieth century or the nineteenth century: the ancient Greeks were talking this way. What this means will vary as you go around the list. There is no cause for the actional principle because all you are doing is, as a knower, inducing a change; but you don’t know what causes the change in the phenomenon itself. In the case of an atomic theory, the cause of motion is preexistent motion; all you have to account for is the transfers or the changes of shape. But even in your holoscopic principles, where the cause of motion is the intelligent whole, if the intelligent whole is not stated to be a transcendent creator, then it’s an equation, and in an inclusive equation there are no causes. They are there but in a form which can be exorcized if you don’t like separate causes in your comprehensive principles. The causes, consequently, are inescapably in the reflexive principles. Notice, then, that in this selection there is already a selection. You may have observed that I’m deliberately not going over the vocabulary: the vocabulary changes are relatively unimportant because the characteristic of language is that meanings are arbitrary; therefore, any word can mean anything and, in fact, does. If, however, you take a look at the substantive side, the selection of holoscopic or meroscopic sets up or eliminates separate causes, and out of this you would get a whole series of other aspects that would appear both in the vocabulary and in what you are talking about.

Let’s turn around and ask, What is going on when you deal with methods? Well, the same business: there are two varieties, the universal and the particular, with the universal divided into comprehensive and operational methods and the particular into logistic and problematic (see table 10). Let me indicate again the formal aspects which may be of interest to you. Since all of this is set up formally, the results grind out without any need to worry about them. The method of assimilation appears on the top part of the line. In fact, the method of assimilation will be on the top half all the way through; it’s the only one that remains there. The method of discrimination moves from the bottom up to the top, the method of resolution moves from the top down to the bottom half, and the method of construction stays on the bottom half. Therefore, in the construction of the families, the close relation that previously existed between assimilation and resolution is broken; and so on with all the others.

Once more, since they’re somewhat similar, between the dialectical and the operational methods it’s a family dispute. And there’s something else that should be said. The family disputes are usually the ones that have the largest literature, whereas the radical disputes you get through with a few expletives such as “meaningless” or “the problem’s unreal.” For example, if you take the methods, in Plato there’s no group that he spends more time on than the Sophists. They constantly appear and they’re always wrong. The elder Sophists—Protagoras, Hippias, Prodicus, Gorgias—he treats with respect; the younger ones, though, are obviously worse, and you get around to people like Thrasymachus, Polus, Callicles. But that’s the family dispute: the methods are similar. In many respects the position which is most opposed to Plato’s and, therefore, endangers it most is the atomistic, below the line. Democritus, the atomists, they are never mentioned in all the dialogues. There are places in two of the dialogues, The Republic and The Sophist, where the physical philosophers, the ones who mistake ideas for rocks and stones and so forth, are taken to task. But it is general description there; learned scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth century put in footnotes that say these fellows are the atomists, but the dialogue doesn’t say so. The dialogues are rather liberal in identifying Eleatics and Pythagoreans and Sophists and a variety of lesser-known breeds. Plato and the Sophists use a universal method. The universal method is a method which can be used in any subject matter; whereas a particular method is a method which is specific to one kind of problem, one objective, one subject matter. Particular methods are plural; these are singular. And the method of the Sophists, like the dialectical method, will apply equally well to morals, physics, and poetics: it’s the same method that is involved.

What’s the difference between them? Well, it all depends on whether you make your beginning point with the knower—the Sophists do this—or whether you make your beginning point from the structure of knowledge which the knower must get to (see fig. 10). The method in both cases is to bring the knower into relation with knowledge. In the one case, he’s stringently held to the requirements of a pattern which influences everything that is and everything which is known. This is dialectic. In the other case, he makes his pattern: man is the maker of all things.—Earlier I think I told you, “Man is the measure of all things”; it should really be translated, “Man is the maker of all things,” because the word in common Greek has this meaning.—Consequently, the criticism of the Sophists that Socrates most usually makes is precisely that their method is arbitrary: they can do anything they want, they can make the worst argument seem the best, they can argue that black is white. Occasionally, an irritated member of the dialogue who doesn’t like what Socrates is doing makes the criticism that he’s doing the same thing: he’s making the worst argument seem invincible. In the Apology, he himself complains that the people who are bringing the charges against him, which led to his execution, mistook him for the Sophists—partly for the Sophists and partly for the natural philosophers. And Socrates would have said this in recognition that not merely did some people make this mistake but that there was something to their mistake; that is to say, the methods are similar to an extent.

The universal methods are both two-voiced, dialogues. They both deal with the process of knowledge as one of interchange and not as a process which an individual can carry on himself—although both will bring out that it is possible to have a debate with yourself or a dialogue with yourself, but even then you are setting out the sides for the two-voiced procedure. As a result, the words that you use in their fundamental meaning are analogical. It is for this reason that Gorgias can begin his treatment of physics with the motion that he describes of mythical entities, and not mythical entities like atoms: these mythical entities are small animals which scoot across the surface of the water in away which he describes in some detail. They’re like atoms, but the operational method always is more imaginative in describing the way things happen. The Platonic or the dialectical method, likewise, will use terms in more than one meaning. For both of the universal methods, then, univocal or literal definition is not a virtue. And let me emphasize this point because we’ve gotten ourselves into a state of mind nowadays in which we assume that if we could define our terms, we would solve all of our problems. This is not necessarily the case even with the particular methods: there’s such a thing as overdefining your terms. But in the universal methods you end with your definition. Your definition is more than a mode of identification: it’s a rich enumeration of the variety of characteristics involved.1

Suppose we take a look at the particular methods. Notice that the main characters of the drama disappear in the particular methods. For the universal methods, you must always remember that the characteristic of the investigator, the measurer, the experimenter enters in—you will recognize that in some of the more difficult problems of modern physics this is back again—or you do it in relation to the large field of structured possibilities that constitutes knowledge. In the particular methods you are going from what has already been established, which you can refer to in your original statement as “the known”—these are equations that the competent scientist will accept as applying to the subject matter in hand—with respect to a region of problems or a structure that you suppose this region has that is beyond the known, the knowable. Therefore, your method is one of two things. Either, beginning with the known, you state what the problem is that you seek to solve, form your hypotheses, test them; and if the formal examination is verified by the experiment, this then becomes part of the known. Or you assume that your previous knowledge justifies you in saying that atoms have certain characteristics that are knowable; these characteristics must, therefore, be applied to this variety of material motion if it is to be explained fully.

Going from the knowable to the known would make the method of science one method. It has usually been called, from the fourth century before Christ, the cognitive method. Anything which is noncognitive, since it would not begin with the elements that your science began with, namely, the atoms or the indivisibles, would be emotive. That is to say, again, you might have feelings, and the feelings would be relevant to an examination of ethics or poetics or the field of persuasion, but it would not be cognitive. And the particularity would come in separating the methods which will give you knowledge from the methods which give you something else. If you begin with the known, there is nothing to prevent your using science in the plural, over the formal mode of expression. Therefore, it would be possible to have a science of ethics which would not be physical; the physical science would not be the only kind, as it would be in the other particular method. If you specified, then, the subject matter in the known, the particular method would in turn be specified by that subject matter. Aristotle, for example, argues that there are theoretic sciences, which have their methods—notice, that’s in the plural—as you move among the various divisions of physics and biology; there are practical sciences, which have their methods; and there are poetic sciences, which have theirs. But the methods are separate, the one from the other.

Notice, as we go along, our philosophic problems become apparent. That is, in this selection when I was dealing with principles, the philosophic problem is the problem of the whole and the part: that’s what holoscopic and meroscopic mean, that’s why they’re baptized the way they are. In this selection, what your meroscopic principles are saying is, All this stuff about wholes is meaningless; there isn’t any whole except the whole you construct out of parts. And what the adherents of the holoscopic principles are saying—and this is an aphorism that has been repeated in the history of philosophy—is, There are parts which cannot be understood in themselves; they have the characteristics that they have by virtue of the whole; and, therefore, unless you know the whole, you don’t know the part. The philosophic problem of method, next, is the problem of universals, and you may have observed that the problem of universals is one of those problems that tends to disappear and reappear. It was strong in the twelfth century; the end of the twelfth century everyone decided it was a meaningless problem. It was strong in the fourteenth century; in the fifteenth century everyone decided it was a meaningless problem. It’s one of our pet problems today, it’s been rediscovered. We have a brand-new set of Platonic idealists, of new realists. But the nominalists have come on strong, too; Mr. Quine2 and others have quite a “to-do” on the problem of the universals. Two decades ago it was a meaningless problem, two decades from now it will be a meaningless problem again, but now it’s strong.

Since I’ve been trapped by time, I’m going to have to stop here. I was going to do interpretation next, and then we could play the game of the interrelations of the three. But it would be silly to start that now since according to the time that you forced on me instead of the one I came in with, we’re already over time and there will probably be a Shakespearean knocking on the door in a moment. Therefore, in the next lecture I will try to recall to you where we have stopped, and if you will keep your notes going, we’ll be able to resume from this point.