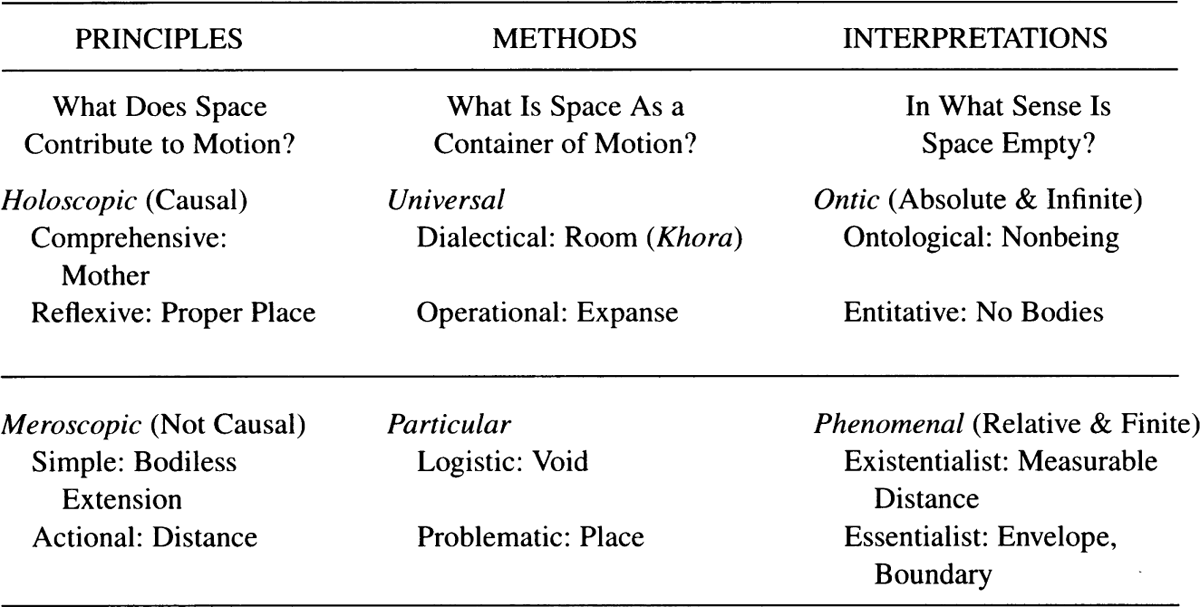

Table 11. Space: Principle, Method, and Interpretation.

Space: Method, Interpretation, and Principle

We have examined the concept of motion and considered the respect in which its meaning is determined by selection, interpretation, method, and principle. I want now to go on to our three remaining concepts: space, time, and cause. In the beginning, you will recall, I pointed out that in a strict sense, the only one of these four which you directly experience is change, that the experience of space, time, and cause is an indirect one. These latter concepts are derived by inference beginning with the experience of change or of motion. If there were no motion, you’d have no reason for conceiving of space, time, or cause. Therefore, what I want to do is to go rapidly through each of them to raise questions concerning what they mean. I think this is important because, first, it will present a kind of test of the methods which we have used in respect to motion and, second, it will serve to enrich the terms. The terms are much more diversified in their meanings than one tends to imagine when one looks at them simply.

What I want to deal with first is space. What is space? I’ve suggested that space, including all the synonyms that we’ve attached around space, is arrived at by inference from motion. Why do you need space to talk about motion? Well, it won’t surprise you to hear that there are three parts to the answer—selection is merely a source of varying the ways of giving the three replies—and I hope that by now the character of the three parts of the reply has become apparent, that it’s not merely machinery. You need space, in the first place, as that in which the motion occurs. This is the answer to the question, What is space?—this is comparable to the answer to the question, What is motion?—and you connect it with method. It would appear to be asking, What is space and what is in space? But you have a second aspect, a second part of the inference. In order for motion to occur in space thought of as a container—to use the word that some of the writers use, considering space as that in which motion is—it’s essential that space in some sense be empty; if it weren’t empty, it would interfere with the motion. Therefore, the various concepts of space will deal with emptiness, but emptiness in totally different meanings. The question, then, which would correspond to interpretation and the meanings of motion that we have in interpretation would be, In what sense is space empty? And a related question which comes up with surprising frequency, though not surprising once you see what is involved in the way in which the question comes up, is this: if space is empty, in what sense does it exist? Space very frequently turns out to be nonbeing; and some of the classic discussions of the senses in which nonbeing is occur precisely because it has to be in some sense or there wouldn’t be any motion—and motion is a curious kind of existence anyway. You’re in the middle, therefore, sometimes applying it beyond physics and sometimes stopping at mechanics; you can move in either direction easily. But there’s also a third aspect of the question. That is, if space is essential to the understanding of motion, in the sense of being essential both to the possibility of motion and to what goes on in motion, then space must have some characteristics which are just the opposite of what we just said, namely, that it’s empty. In spite of its emptiness, space must contribute to motion in some way: a pure negation wouldn’t do. This, then, is the question which is connected with principles.

I think that probably what is advisable here is to go rapidly, so I will now give you twelve aspects of the meaning of space. I suspect that to run through them quickly would possibly be better than to give you considerable detail because in each of the aspects that we will deal with, space ought to appear to have meanings which you would not at first have attributed to it. Let me begin, as we have in the past, with method. If you consider method, it would be easily apparent that we ought to run into something that would look like a universal space and something that would look like a particular space, and the two varieties of space would contain different things. The universal space would be the space that would be required for those universal motions which we discovered by the universal methods, whereas the particular space grows out of a motion which we found by the particular methods. When we were talking about motion, I pointed out that the Greeks had four different words for space,1 some of which we’ve identified later as we got to our readings in Galileo and Newton. Remember, in the course of later development, you borrowed your rival’s words; therefore, the original strict sense will not continue. In the original strict sense, then, the universal space for Plato is Khora, or room. The universal space for the Sophists is a little difficult to translate: let me call it “expanse,” “dimension,” “distance,” or, if you’re careful to keep extension to its mathematical sense, “extension.” The particular spaces are the void and place. Let’s examine what they mean and why you got into them (see table 11).2

I think that it would probably be safer to begin with the particular spaces, because the particular spaces are the literal spaces and they are the spaces that you will recognize more easily. What I want to get you to see, however, is what the universal spaces are, because they are not spaces in which bodies are. By the logistic method—you’ll remember, that’s the one that began from the knowable and went to the known (see fig. 10)—we came to the conclusion that the only motion was local motion, that only bodies moved. Consequently, it would follow that the motion of bodies would take place in a void. This is the container of local motions if local motions are taken in the logistic sense. Bear in mind that all of these methods will be able to deal with local motion, but this is a method which reduces every motion to local motion and, therefore, it’s the only motion that exists. Consequently, if you consider the void as a container, the only thing that the void can contain is bodies. This is our first meaning.

The other particular method, the problematic, is where you go from the known to the knowable. Motion, Aristotle said, is the actuality of the potential qua potential; but all the actualities that are involved in motion are existent in bodies, and, therefore, the only things that move are bodies. There are more than local motions, however, because bodies are substances. You can have generation, which is a change of substance; you can have a change in the properties of a substance; and the only situation where place comes in directly is in local motion, where you move from one place to another, though place is involved in all of the other motions. Take, for example, increase and decrease, which is a change of size. As the body swells, it fills more place than it did before; yet the increase is something different than local motion, although it would involve local motion. If you were increasing the girth of a man, for example, it would involve the local motion of the skin around his stomach, at least, out into other space. What is place, according to Aristotle?—Notice, place is one of the words that Newton wanted, as well as space.—Aristotle defines place as the internal limit of the envelope surrounding a body. The place of the lectern would be the series of particles of air that lie precisely around the shape of the lectern. For Newton, place is occupied space. You’ll notice—again leaving out the other uses of place—that for Aristotle and the other men who use the problematic method, the important thing is that place would be this envelope, and people in this position normally refute the possibility of the void. Aristotle was such a man: he had place, but he had no void. He had very nasty things to say about the atomists, who did have a void: the absurdity of the conception, the meaninglessness of the question, and a variety of other things—he’s very modern in the way in which you dispose of your adversary. Place, then, is a container of bodies, and the only things that are contained in place as a container are bodies. To sum up the two particular methods, then, space as a container would be either the void or a place, that is, a boundary which, as a container, would contain only bodies.

Let’s take a look, now, at the universal methods. What would you have as space for the dialectical method? Well, we found that the characteristic of dialectical motion differed considerably from that of the particular methods. Motion here turns out to be a series of instantaneous generations. If you take anything, even a thing moving in space, you can break it up into a series of steps; and at each step you have a generation that is different from the prior one, a generation that is fully a generation and not merely a change of quality, which is the way Aristotle would speak of any of the motions that are not the generation of the substance as such. Motion as generation, then, would include all changes, without a need to reduce the changes to changes of bodies. It would include changes like thinking, learning, reciprocating love with love or love with hate, doing justice or suffering justice, improving or retrograding in any respect. “Room” is the container of all these motions, and it’s a container in the sense of being an aggregate of all of the possibilities that can be realized. Room means potentiality. The example in the Timaeus3 is that if you take a piece of gold and mold it into various shapes—it’s a globe or sphere one moment, a square another moment, a cylinder another moment, or it’s even melted—and if you point to it as it undergoes these changes and say, “What’s that?,” the right answer is, “Gold.” Gold, therefore, is the room in which all of this is realized. Or, to generalize: when you are dealing with any process of change, there must be the potentiality there before you can have the actuality.

This, incidentally, is a form of thought which had a great vogue as one looks back over the long history in which pragmatism had a vogue and neorealism had a vogue and logical empiricism had a vogue and analytical philosophy had a vogue. There was a vogue which I found very attractive in my youth: it was the Gegenstand ["object"] philosophy. Has anyone heard of it? I mean, if you want to join a cult, this is the one to go for. [L!] Meinong4 was probably the great writer in this tradition, and Meinong influenced Husserl—if you don’t derive Husserl out of Kierkegaard and Pascal and St. Augustine, you can derive him out of Meinong, Brentano, and Thomas Aquinas, an equally interesting history. But if, to use a crude example, you want to talk about the circular area outside this building on which we have devoted our energies to cultivating grass and ask, What is it as a room?, it’s all of the things we could have done with it besides growing grass on it: it is a thirteen-story, modern library, air-conditioned [L!],5 and so on. That is, anything which is a possibility is there in the sense that if you got going and made it real, you would only be working among the things that are possible—and there are a whole series of things that are not possible out there. The room, then, is the collection or the aggregate of the things that are possible.

Finally, let’s take the operational method. In the operational method you move from knower to knowledge. Now, all motions are not generations; rather, they’re measured changes in which the knower either measures or makes the change, and in point of fact, as early as the Sophists it was recognized that there’s no great difference between these. The Copenhagen school, all of the investigations of quantum mechanics, these are in this position now; namely, that in the process of measuring these fine changes, the measurer gets in the way, and it’s so hard to tell whether he’s measuring or making that you can’t separate the two. Consequently, all change would be of this sort. This kind of change would include changes of bodies, but you would not reduce them all to changes of bodies. What is space? Well, space is expanse, it’s measured distance, it’s any formulation of measure which, in turn, you could then apply to something. Therefore, if you find, as Galileo did, a form of geometric development which fits nature, though it’s unlike the conchoid or unlike the helix, then you would bring nature in; but you could go on with your measuring even with the conchoid and the helix. The differences between expanse or extension and what it is that you apply them to would be an indication of what it is that makes space a container.

Let me say a word about the difference between expanse and the void. They may look as if they are similar, whereas nothing could be further from being the case. The void contains only bodies. Expanse, however, contains anything which is distinguishable from anything else, and the measures of the things are the distances in the expanse of such things and observers. Note that for universal space, there is the doubling that I mentioned earlier. For all of the modes of distinction above the line, you have two senses, and they are easy to see. Universal space includes particular space, but particular space does not include universal space. If you deal with the kind of space in which all generation occurs, you can shift gears and deal with the kind of space in which bodies move; and, similarly, if you deal with the measurements which include anything that can be differentiated, you can make some measurements, some figures, which you can then try out to see whether they fit bodies in motion. The particular spaces, then, are just one of the meanings of the universal spaces, and the latter would always involve the theorist who engages in them in speculation also about the particular spaces.

Let’s go on to interpretation. Interpretation would be an answer to the question, In what sense are the spaces that we’ve been talking about empty, and if they’re empty, how can they exist? And there are two kinds of space that will appear: the absolute space and the relative space. Let me anticipate by saying that the doubling of absolute space means that where you have absolute space, you will need to have relative space as well. If, however, you are a proponent of relative space, you will say, There is only relative space; we have neither a need for nor any device by which we could detect absolute space. The ontic space is the absolute space; the phenomenal space is the relative space. All that the word means is that the phenomenal is the experienced space; the ontic is the space which, in some sense, is outside the experienced space. Let me also, by way of anticipation, alert you to another distinction which might look like this. Among the relative spaces there will be one variety which will want to talk about proper space and common space. In other words, the proper space of the lectern, since I used that before, is the layer of materials just around it; the common space of the lectern is the room or the building or the city. But this is particular because, you’ll notice, I haven’t shifted gears; I’ve merely taken a larger and larger unit. We are talking about absolute and relative, which would include the manner in which we would try to deal with them and the manner in which we would deal with their interrelations; and we would necessarily detect them, measure them, use them differently, not merely get a bigger foot rule.

The ontological space—and this is going to be room, again, if you want to take Plato’s version of ontological space—is space concerned with being; and the sense in which the space concerned with being is empty is, naturally, that it’s empty of being: it’s nonbeing. Plato goes through this argument a great deal; he does it in the Timaeus and does it again in the Sophist. In order to have motion at all, you must have nonbeing. The six categories that he comes to at the end of the Sophist are categories which begin with being, then you go on to motion and rest, same and other, and eventually you discover that you can’t explain how these are possible unless there is nonbeing, nonbeing which separates the same from the other. For Plato, this is true simply in order for any change to occur.

Suppose you then move from this. What about room as a particular instance of this? Well, room in the Timaeus is empty in the sense that it has all the potentialities but doesn’t have any of the actualities which are involved. Plato gives a second analogy—I’ve given you the first: the gold which takes on different shapes. The last time I mentioned this,6 I pointed out that it’s the same figure that Descartes uses when he appeals to wax, which can take different shapes. Plato, being more of a technologist, was going to break down a harder material than Descartes was; otherwise, the thought that’s involved is exactly the same. But there’s a second figure that Plato uses. Room, he says, is like the oil or the base the perfumer uses when he wishes to fix his odors. The one requirement it has is that it must not smell; if it is odorless, then it is a good medium in which to fix a perfume. Room is like that: room lacks the actualities that would be relevant to the processes that are in question; therefore, it would not interfere with them. It has to be empty because otherwise it would interfere with the process itself; similarly, if the oil that the perfumer used had a smell, he wouldn’t get the perfume that he was trying to preserve in the bottle. Room is empty, then, in the sense of having none of the actualities whose potentialities are to be realized; and it would be empty both in the case of absolute space, where you are dealing with real generation, and in the case of relative, experienced space, where you are dealing with some minor change, such as the changes I’ve used in the example of moving my briefcase.7 In other words, for both you would need room. In the case of absolute space, the space would be absolutely qualityless. In the case of relative space, it would be qualityless with respect to what it is, just as my briefcase has a great many qualities when I’m moving it locally. The room is merely a local room; if I changed its color, the room would have to do with the colors that would be involved.

Having just dealt with the ontological variety, let’s turn to the second kind of absolute space, the entitative. The void is empty in the sense that it contains no bodies. As a matter of fact, if you look at the early fragments describing Democritus, the thing that’s most frequently said about him is that he took the pair of contraries, being and nonbeing, which the pre-Socratics before him had been playing with and did something radical with them. Instead of taking them as all-inclusive and making it necessary to choose between them, he made being extremely small, made nonbeing extremely small, and then said, Both are. One of the most famous fragments that has come down to us from Democritus is that a thing is no more really than nothing is; in other words, space is just as really as the atom is. Consequently, by taking them in this sense, you make space empty in the sense of absence of bodies in it, and motion takes place because there are not bodies which interfere. You need the absence of bodies because otherwise, if there were a pseudo-body that would interfere, the motion of body and body would be unintelligible. In the entitative, then, absolute space is the immovable space in which a body is situated. Relative space is the space within either a system or a body that is moving with respect to absolute space, which is practically the same as the distinction you find in Newton.

For the ontic interpretation, then, there are two kinds of absolute space. There’s the absolute space of generation and the absolute space of locomotion. The one is empty of change other than the changes that would occur in any generation; the other is empty of changes of the variety that occur when a body moves in space. Take the first, the ontological. The doubling of the meanings occurs in that you would deal with motion in two ways. There is, in the first part of the Timaeus, a treatment of motion in terms of reason; and, therefore, it’s the motion of the soul that comes first. Remember, the soul of the world is divided into two parts: one has the motion of the same, the second has the motion of the other. You mix them together, and this moves the entire universe. This is the treatment relative to the universe as a whole. But in the second part of the Timaeus you get to the motion of necessity. Here you’re dealing first with the interrelations of the elements and the ways in which they join or change into each other; and then you need relative space, that is, space which will permit you to move from one to the other. For the entitative, you would have, first, in absolute space the motion of bodies relative to an unmoving space; secondly, in relative space the movement of bodies relative to other bodies.

There’s one final point to be made, and this came as a surprise. Suppose you want to know whether space is infinite or not. It looks like an empirical question. In all the documents that I have read, if a man makes an ontic interpretation of space, he always discovers, sometimes with great empirical care, that space is infinite. It’s finite only for the phenomenal interpretations.

Let’s move, then, to the particular interpretations. First, the essentialist. What exists are substances, substances and their properties—this is Aristotle, but there are only slight variations in the essentialist interpretation. The changes of substance are generation; the changes of the qualities of substances are motions, and among the motions are the motions in place. You have place, which is the place only of bodies—you don’t apply it to anything except bodies—and which is the internal boundary of the envelope surrounding the body. Consequently—and I want to make this point strongly—the sense in which it is empty is simply the difference between a boundary and the form which makes the body. Notice, when you put it this way, the two have exactly the same shape. The form of the desk that is the desk—kind of heavy—is the material object. The place of the desk, which has the same shape, is empty; yet it is in close relation because even if I move the desk out, the place of the desk would be that designatable boundary which I could indicate on a plan or on a blueprint. This is the sense of emptiness. Notice, it’s quite a different sense from either of the two senses that we had above.

What about the existentialist interpretation? Well, for the existentialist interpretation, you will recall, we are dealing with motions which are movements of the agent, so what exists is what is made and what is interpreted. Let me reiterate, this is not so strange, particularly today when a good many of the existentialists who call themselves existentialists and are phenomenologists take this position. In other words, you begin with the phenomenological present and you order your experience—as Husserl calls it, you set up different intentionalities. Out of your experience, if you’re a poet, you may imagine a poetic world; but if you’re a physicist, you may work out the equations that will operate in mechanics or dynamics or any of the other fields of physics. And according to Husserl, what you’ve done in these two instances is exactly the same: in the one case you’ve made a poetic world, and in the other case you’ve made a physical world. What you began with was the same phenomenological present; then you worked it out according to your abilities, and you need as much training and genius in the one as in the other. The result in one case is a physical world; but it’s a mistake to think that the physical world is somehow prior, that the poet lives in a physical world which he then gets slightly askew in his poems. You have, rather, the experiencing poet, the experiencing physicist, and the making of these two worlds.

What is space, then? Well, space is merely the measurable distance in any such process. It’s the measurable distance of the moving body which the physicist is working with; but if you had a psychologist setting forth the conditions in which he’s examining his phenomena, doing it precisely enough to be able to determine how far his data are from his finished result, that’s space, also, that’s a measurable distance. Gorgias likes to talk about little animals skimming along the top of the waves.8 Although he was thinking of this as a pure myth, a mode of change only imagined, it is still a measurable space.

How is it empty? It will sound something like the essentialist, but it is different. That is to say, it is empty in exactly the same way that dimensions are empty of the object.9 Suppose you have a man working within the tradition that we are talking about who has set up an equation, who goes through the empirical investigations to discover whether this equation is indeed the one that would fit the circumstances, who moves back and forth, sometimes altering his data, sometimes altering his equation.—And don’t look shocked: it’s what scientists do. They sometimes alter the one and sometimes alter the other; it’s all their process of constructed interpretation and it doesn’t matter much, provided one does it well.—The equation, until he got it adjusted, would be empty; the equation when stated as what happened in the situation that he is describing would be the object that he had constituted. Bear in mind, he is constituting the physical world. When he gets his dimensions such that they will really hold, then it is like the lectern; all of the equations before were the dimensions that he was applying, which were a little different. There’s a difference between boundaries and dimensions: that is, in the first case, we begin with a physical object and get its boundary; in the second case, we begin with an equation and hunt around for things that will fit in the equation. They merely balance each other as two approaches.

We have only four more meanings, principles. A principle bearing on space would be an answer to the question, What difference do these different conceptions of space make in the interpretation of motion? Remember, as I said, in interpretation we want to know why space is empty; now we want to ask what it is that space contributes to the possibility. Well, there are two main approaches. There is space as a whole and space as a part, the holoscopic and the meroscopic. If space operates as a whole, it can operate in one of two ways: both of them would be space as a cause. Let’s take the comprehensive principle first, and again we’ll use Plato. The maker is the cause. He is the cause in the sense that he introduces the rational order in the chaos that he found before; therefore, the entire first part of the Timaeus deals with the maker as a cause. Next comes the second part, in which, you’ll recall, you go in the opposite direction: you get your elements and you construct the universe from them. Then Timaeus pauses because we need another principle. What we’ve got to deal with is the interrelation of the elements with each other. There are three principles, he says: there is the father, or the maker; there is the offspring, or that which is created, that which is made; and there is the mother, the receptacle, the room. The mother is potentially everything that occurs. Notice, you need the mother only when you’re dealing with these complex interrelations among elements. Obviously, when you’re dealing with the motion of the whole, the question of space does not come in, you don’t need space. You need potentiality only when you’re within the universe dealing with interrelations. If you’re dealing with the whole universe, you’ve got it all; therefore, changes don’t involve potentiality.

Secondly, you could do it by means of reflexive principles. Reflexive principles would not engage in this large form of speculation that comprehensive principles do. Place, as opposed to room, is the container only of bodies; but you can talk about the proper place of a body, and the proper place of the body is so constituted that if the thing is not in its proper place, it will move into its proper place. Heavy things move down; light things move up. It’s too bad that this idea is one of the things that Aristotle set going in a way which now seems so clearly wrong, but it’s just as rational to say that air and fire move up and water and earth move down as to say that gravitation moves in only one direction; we just haven’t said it for a long time. But in any case, this means that place exercises a causal efficacy, just as room as potentiality enters causally. And there’s a doubling: in addition to this causal element you can have space merely as the dimension.

When you get to the meroscopic, to space as a part, however, it is only as a dimension or as a principle. Take the actional principle. In the actional principle, space is a distance, it’s d. It is important that d have characteristics: it should be divisible to infinity, for example; it should not have lumps in it which would prevent its dividing; and if you say, d = vt, then d is a principle. But distance doesn’t affect the motion; it isn’t a cause.

Suppose you take simple principles. The void is an absence of bodies; only bodies are causes. The void provides the possibility for the operation of causes, but it’s a principle and not itself a cause. Bodily extension without bodies makes motion possible but never causes any motion.

Let me conclude with a few remarks. For each one of these approaches, there are a number of things that look like empirical conclusions which turn out to be merely consequences of the mode of analysis you begin with. I pointed out that if you have absolute space and relative space in the strict sense that we’re using it here, not in some of the varieties, space will be infinite; whereas, if it is only relative, it will be finite. Likewise, there’s a very serious issue with respect to our principles. The difference between space as a cause and space as a principle seems to become prominent only when you are dealing either with the interrelations of least parts or elements or atoms, or with total motion. The two tend to go together: even today, our cosmology and our quantum mechanics tend to get merged one with the other very quickly. But what is it that brings this about? Suppose we wanted to know whether there was any such thing as an element. Are there indivisible parts? It would sound as if this were an empirical question: we could try cutting them up to see whether they’re indivisible or not. Can you have the elements transmuted one into the other? Well, the curious thing is that from the beginning, for all the holoscopic principles you have the transmutation of elements, and for all of the meroscopic principles you have indivisible parts which cannot be translated. It’s been an argument for a long time. You’ll notice, it is not something where you can say, “Well, finally we’re in a position in which we can test it empirically,” because the manner of division changes as you go along. Consequently, the respect in which the transmutation would be conceived and would operate for your universal principles will be totally different from the respect in which it would be conceived and would operate for your meroscopic principles. It is more nearly the case that they’re talking about different processes. I did an essay some time ago on the different criteria that are used in the determination of elements.10 It’s an extremely long list. Some of the criteria are inevitably connected with meroscopic principles: these elements will never be transmuted. Some of the criteria are connected with holoscopic principles: they will give you elements which will be transmuted, even if you’re an atomist.