Advertisers … there’s $6 Billions [sic] waiting for you in WFIL–adelphia. SELL ALL of America’s 3rd market on WFIL–TV. You can really go to town—to hundreds of towns in the rich Philadelphia market—on WFIL–TV.… Get the most for your money, the most people for your money. Schedule WFIL–TV.

—WFIL–TV call for advertisers, Philadelphia Inquirer, 1952

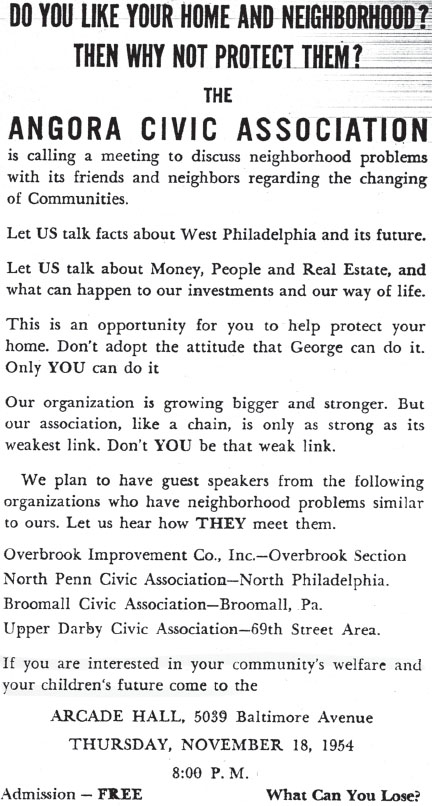

Do you like your home and neighborhood? Then why not protect them?

—Angora Civic Association flier

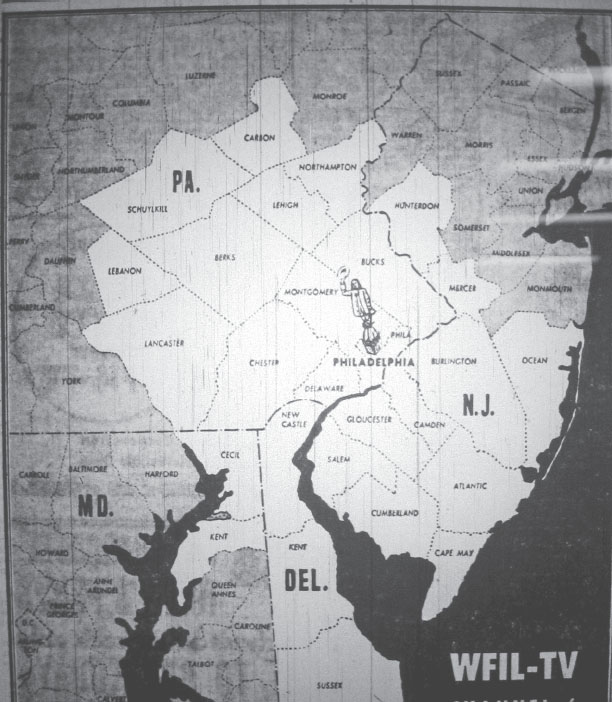

Throughout 1954, white and African American teenagers fought outside of WFIL–TV’s West Philadelphia studio on an almost daily basis. Philadelphia experienced more than its share of racial tension in this era, but these teenager brawls stand out because they were sparked by a television program. WFIL–TV broadcast the popular, regionally televised teenage dance show Bandstand (which became the nationally televised American Bandstand in 1957). It broadcast Bandstand to parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, a fourstate region it called “WFIL–adelphia.” In its calls for advertisers, WFIL emphasized the station’s ability to help advertisers reach millions of these regional consumers.1 WFIL–TV was a particularly lucrative advertising venue because it was part of Walter Annenberg’s media empire, which also included WFIL radio, the Philadelphia Inquirer, TV Guide, and Seventeen magazine, among other properties.

At the same time WFIL aimed to capitalize on its regional market, the area around the station’s West Philadelphia studio became a site of intense struggles over racial discrimination in housing. Just blocks from Bandstand’s studio doors, white homeowners associations and civil rights advocates fought a block-by-block battle over housing. Groups of homeowners like the Angora Civic Association sought to prevent black families from moving into West Philadelphia. The racial tensions around Bandstand’s West Philadelphia studio threatened to scare off the advertisers who funded the show and forced Bandstand’s producers to take a position on integration. Fueled by the show’s commercial ambitions, the producers chose not to allow black teenagers to enter the studio. By blocking black teens from the studio, Bandstand, like the white homeowners associations, sought to protect homes from the perceived dangers of integration.

The respective efforts of WFIL and the white homeowners associations to maintain segregated spaces constituted overlapping and reinforcing versions of “defensive localism,” a term used by sociologist Margaret Weir and historian Thomas Sugrue to describe the way homeowners associations emphasized their right to protect their property values and the racial identity of their neighborhoods.2 As historian David Freund has shown, white homeowners in the postwar era expressed a deeply held belief that black people posed a threat to white property values. This way of viewing race was significant, Freund argues, “because it allowed whites to address their racial preoccupations by talking about property instead of people.”3 In Forbidden Neighbors, his 1955 study of racial bias in housing, Charles Abrams noted the pervasiveness of this link between race and property values:

Homeowners, home-builders, and mortgage-lenders seemed convinced that people should live only with their own kind, that the presence of a single minority family destroys property values and undermines social prestige and status. National and local real estate organizations were accepting these assumptions as gospel, as were popular magazines, college texts, and technical journals.4

As Abrams notes, the federal government and private mortgage lenders directed housing loans to maintain segregated housing markets. At the neighborhood level, white homeowners associations used covenants and violence to protect what they viewed as their right to live in racially homogenous neighborhoods. The term defensive localism is useful to understanding white mobilization for segregation because it links the monetization and racialization of space. As in other northern cities, anti-integration forces in Philadelphia seldom used explicitly racist language to defend their position. Rather, racial integration was rejected as a threat to property values. This logic applied not just to homeowners, but also to the television stations and advertisers that sought to reach them. Figured in this way, the pursuit of profit, in this case through home equity or advertising revenue, could be used as a defense of racial prejudice and de facto segregation. Indeed, while homeowners associations fought to protect their home investments by keeping their neighborhoods exclusively white, WFIL fought to protect the commercial prospects of the fledgling Bandstand by making the show’s representations of Philadelphia teenagers “safe” for television viewers in WFIL–adelphia.

WFIL’s description of its four-state broadcast area as WFIL–adelphia points to the fact that postwar television was both urban and regional, that it was both a physical site of production and a network of viewers and advertisers responding to televisual images. Media studies scholar Anna McCarthy describes this as television’s capacity to be both “site-specific” and “space-binding.”5 These qualities were in tension for WFIL. The everyday actions in Philadelphia and the images broadcast across WFIL–adelphia influenced each other in important ways. The station and its advertisers wanted access to the population, spending power, and creative potential of the nation’s third largest market without any of the perceived problems of broadcasting from an urban area with a racially diverse population. With Bandstand, WFIL resolved this tension by drawing on Philadelphia’s interracial music scene to create an entertaining and profitable television show, while refusing to allow the city’s black teenagers into the studio audience for fear of alienating viewers and advertisers. Like the white homeowners associations’ concerns about property values, WFIL’s version of defensive localism built on a belief that integration would hurt the station’s investment in Bandstand. When WFIL’s Bandstand broadcast images of white teens on a daily basis, it disseminated the anti-integrationist views held by homeowners associations across a large regional broadcasting area. This broad view of defensive localism, stretching from the local homeowners associations around WFIL’s West Philadelphia studio to the station’s racially exclusive admissions policies on Bandstand, illustrates how housing and television formed overlapping and reinforcing sites of struggle over segregation and how the everyday material reality of race in Philadelphia intersected with media representations of race in WFIL–adelphia.

WFIL opened its West Philadelphia studio at 46th and Market Street just before Bandstand debuted in 1952. The studio housed all of the station’s radio and television operations and sat next to the Market Street elevated train that connected West Philadelphia with center city to the east and Upper Darby to the west.6 While Market Street featured primarily storefronts, the area surrounding Bandstand’s West Philadelphia studio included a mix of residential housing, including two- and three-story row homes, three-story Victorian semidetached “twin homes,” low-rise apartment complexes, and a smaller number of detached single-family homes. Although the area was less densely populated than South Philadelphia and North Philadelphia in the early 1900s, West Philadelphia experienced a period of rapid urbanization from 1910 through 1940; by World War II, the area housed almost 20 percent of the city’s total population.7 The racial demographics of the city, and especially the area around WFIL’s West Philadelphia studio, were changing rapidly when Bandstand debuted.

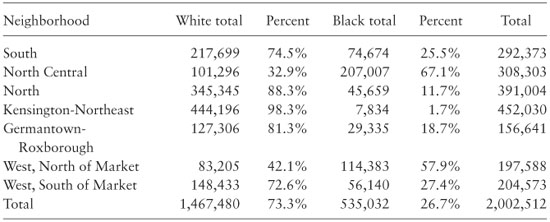

Demographic figures convey the scope of racial change in Philadelphia in this era. From 1930 to 1960, the city’s black population grew by three hundred thousand, increasing from 11.4 percent of the city’s total population to 26.4 percent. The changes were similarly dramatic in West Philadelphia. The black population expanded in West Philadelphia after World War I and settled primarily in the area between 32nd and 40th Streets and from University Avenue to Lancaster. This eastern section of West Philadelphia, then called the “black bottom,” expanded again in the 1940s and 1950s. Working-class blacks were drawn to the area because of strong neighborhood institutions and opportunities to rent apartments and houses denied them in other parts of the city. By the 1950s, the “black bottom” was a vibrant neighborhood of businesses and row homes, 15 to 20 percent of which were owned by black families.8 Through the 1940s and 1950s, as many white residents moved to new suburban developments in other areas, West Philadelphia’s black population continued to expand further west and north. The increase first occurred above Market Street, an area with many subdivided housing units and lower rents. Through the 1950s and 1960s, black families expanded to the west of the “black bottom” on the south side of Market Street, where homeownership opportunities were greater.9 By 1960, the black population in West Philadelphia was the second largest in the city.10

These statistics, however, do not adequately convey the block-by-block struggle over housing. Racially discriminatory housing practices fueled the concentration of blacks in West Philadelphia and other neighborhoods. Private housing developers openly discriminated because they believed their white customers wanted segregated neighborhoods. As the former president of the Philadelphia Real Estate Board acknowledged, “most of the people when purchasing or renting homes place great value upon exclusiveness in terms of religion and ancestry, and particularly to color. These desires are in conflict with the basic concept of the open market.”11 Fair-housing advocate Charles Abrams also noted that builders could accommodate white home buyers’ racial prejudice without raising the price of the home. “Unlike the tiled bathroom, venetian blinds, and television outlets,” Abrams noted, “the promise of racial exclusiveness cost the builder nothing.”12

These real estate practices severely limited the housing options for black Philadelphians. A 1953 Commission on Human Relations study of new private housing in the Philadelphia metropolitan area found that only 1,044 of more than 140,000 recently constructed units (less than 1 percent) were available to blacks.13 From 1946 to 1953, only forty-five new homes were offered for sale to blacks. With their options limited by racially restrictive covenants and mortgage redlining, the other twenty thousand black families who became homeowners in this period bought secondhand houses at higher financing charges.14 Historian Beryl Satter has shown how speculators profited by selling houses to African American on exploitative terms. “The reason for the decline of so many black urban neighborhoods into slums was not the absence of resources,” Satter argues, “but rather the riches that could be drawn from the seemingly poor vein of aged and decrepit housing and hard-pressed but hardworking and ambitious African Americans.”15

This widespread housing discrimination posed a challenge for the city’s Commission on Human Relations (CHR). The city’s voters passed a city charter in 1951 that established the CHR to administer antidiscrimination provisions in employment and public accommodations. The CHR’s first annual report declared that, with support from the city’s administration, the CHR’s “substantial powers of investigation,” and “strong community backing mobilized by the Fellowship Commission,” the city had assembled the tools for an “effective attack on racial and religious prejudice and discrimination and for building rich and wholesome relationships among the racial, religious and nationality groups that make up America.”16 The creation of the CHR encouraged many Philadelphians to see their city as a leader in racial equality. At the same time, however, the CHR lacked the power to address housing or educational discrimination, and its case-by-case approach to employment discrimination was overwhelmed by the number of complaints received.17 For its part, the Fellowship Commission, the city’s leading civil rights coalition, prioritized fair employment legislation over fair-housing legislation before eventually lobbying the state to enact a narrowly tailored housing bill (excluding private sales of owner-occupied houses) in 1961.18 Without fair-housing legislation, black residents in West Philadelphia and other neighborhoods continued to face a restricted housing market throughout the 1950s.

TABLE 1 PHILADELPHIA POPULATION BY RACE, 1930–1960

SOURCE: U.S. Census.

TABLE 2 PHILADELPHIA POPULATION BY RACE AND NEIGHBORHOOD, 1960

SOURCE: Commission on Human Relations, “Philadelphia’s Non-White Population 1960, Report no.i, Demographic Data,” CHR collection, box A-621, folder 148.4, PCA.

In addition to restrictive housing covenants, white homeowners organized in neighborhoods across the city in order to block what they viewed as the encroachment of black families in all-white neighborhoods. These groups emphasized their right to protect their property values and the racial identity of their neighborhoods. In West Philadelphia, the Angora Civic Association (ACA) sought to prevent black families from moving into the Angora-Sherwood sections of West Philadelphia, along Baltimore Avenue from 50th to 60th streets. The ACA resembled white homeowners’ groups that mobilized to maintain segregated neighborhoods in Chicago, Detroit, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Miami, Houston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and elsewhere across the country.19 These groups used a range of tactics to achieve their aims, including mob violence and physical and mental harassment. While the homeowners’ groups were a nationwide phenomenon, the Angora Civic Association is noteworthy because of its proximity to the WFIL studio and because the group’s founding coincided with Bandstand’s debut.

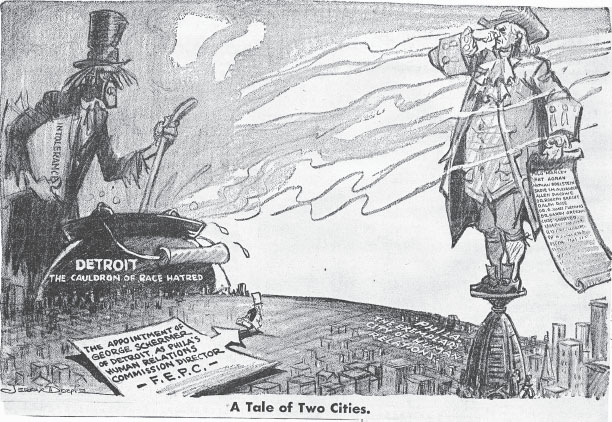

FIGURE 1. Philadelphia, “The Exemplary City of Human Relations,” turns up its nose at Detroit, “The Cauldron of Race Hatred.” This 1952 editorial cartoon questioning the appointment of Detroit’s George Schermer to head Philadelphia’s Commission on Human Relations captured the feeling that Philadelphia was a leading city in antidiscrimination laws and programs. December 30, 1952. Jerry Doyle / Philadelphia Daily News.

Starting in 1952, the ACA distributed fliers and held meetings encouraging its neighbors to exercise their rights as homeowners. A contemporary study of the racial change in this West Philadelphia neighborhood noted: “The entry of nonwhites appears to have come as a heavy shock to white residents, and a severe panic existed through 1954.”20 Indeed, the language in the association’s meetings and fliers stressed the white homeowners’ anxiety at the prospect of a racially changing neighborhood. One meeting notice invited residents in this section of West Philadelphia

[t]o discuss some very serious problems which are confronting your neighborhood NOW. One of these problems may be right in your block, or even as close as next door. At any rate one of them cannot be very far away. One thing we can assure you of is that they are not mythical or imaginary, but very real, and will require very real concentrated and realistic attention if you want your neighborhood to remain as it now is.21

Another flier asked: “Do you like your home and neighborhood? Then why not protect them?”22 Aware that members of the CHR and Fellowship Commission covertly attended their meetings, the homeowners’ groups avoided racist epithets in favor of thinly veiled references to neighborhood “problems” and “undesirable” neighbors. In the ACA’s view, keeping black families from buying houses in the neighborhood would protect both the racial identity of the neighborhood and the property values of the homes. Since homeownership represented a significant financial investment in this working-class and middle-class area, fears of blockbusting and panic selling fueled the ACA’s economic anxiety. A meeting announcement warned: “If you are ready and willing to throw away thousands of $$$ for what you now have and own, then throw this notice away and don’t read any further.”23 The ACA regularly drew between fifty and three hundred people to its monthly sessions, and as many as seven hundred attended its most popular meetings.24 Although the historical evidence does not allow a close analysis of the association’s membership, meeting records include names such as Petrella, DeRosa, Callahan, Vandergrift, Craig, Stahl, and Rabinowitz, suggesting that individuals from several white ethnic groups participated.25

At its best-attended meetings, the ACA invited leaders of similar white homeowners’ groups from other parts of the city to share tactical ideas and offer support. The leader of the eleven-year-old Overbrook Improvement Co., for example, told the ACA of his group’s success in keeping blacks out of the Overbrook neighborhood in the northwest section of West Philadelphia. The Overbrook group president, Harold Stott, recommended “putting pressure on real estate men, banks and mortgage companies,” and he advised the ACA to raise money to buy houses in the neighborhood so that they could be resold to whites rather than blacks. While these homeowners’ groups did not openly advocate violence, they suggested that white residents should try “psychological methods.” These methods included repeated visits by white neighbors asking the “undesirable” family to move, vandalism of property, and threats of violence to dissuade black families from moving into the neighborhood and to convince those who did manage to buy houses to sell their homes to the corporation and move out.26

Throughout these meetings, the ACA, Overbrook association, and other groups stressed both the urgency and the legality of their cause. “Help!! Help!!” proclaimed one meeting notice. “These are words we hear every day from the Property Owners of our Community. Our Association can render you this help If You Want It!” This notice ended with an ominous evaluation: “IT’S LATER THAN YOU THINK!”27 This language resonated with similar appeals to antiblack prejudice in Philadelphia during and after World War II. Historian James Wolfinger has shown that Republican campaign brochures that circulated in Irish and Italian sections of West Philadelphia during 1944 used similar language to warn residents that “black domination” threatened their city. “Will you stand by and see our homes, schools and our entire neighborhood taken away from you and your children by a race stimulated by RUM— JAZZ—WAR EASY MONEY?” the pamphlet read. “Vote a straight Republican Ballot next Tuesday and save your salvation.”28 Additionally, fliers linked to a resurgent Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia in the early 1950s urged white men to join forces for “the protection of homes and loved ones.”29 Despite appealing to racist sentiments, the white homeowners’ groups defended their calls to action by asserting what they viewed to be their legal rights as truly American homeowners. The Overbrook group president told the 120 residents at the meeting that the members of the ACA “are 100% Americans. All they are asking is to keep the high standards of their own neighborhood and to pick their neighbors besides protecting their property. In doing this they are exercising their rights under the Bill of Rights and there certainly is nothing un-American about that.”30 This rights rhetoric cast the homeowners’ groups as possessing an Americanness—and whiteness—threatened by black interlopers. As David Freund notes in his study of suburban Detroit, this language of property rights enabled whites to mobilize for segregation as homeowners, citizens, taxpayers, and parents while maintaining that they were not racist.31 In his study of California’s ballot initiatives, political scientist Daniel Martinez HoSang describes this rights rhetoric as central to a set of “norms, ‘settled expectations,’ and ‘investments’ [that] shape the interpretation of political interests, the boundaries of political communities, and the sources of power for many political actors who understand themselves as white.” Like the “political whiteness” HoSang identifies in postwar California, white homeowners associations fought to protect “our neighborhoods,” “our kids,” “our property values,” and “our rights,” while claiming to be innocent of racism.32

FIGURE 2. The Angora Civic Association distributed thousands of fliers like these to recruit community members to its meetings. White homeowners’ groups and civic associations from other neighborhoods attended these meeting to show support and share tactics. November 18, 1954. Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

These white homeowners’ groups also directed their defensive localism and rights discourse toward the Fellowship Commission’s civil rights work. The leaders of the Angora and Overbrook associations accused the Commission of forcing its integration agenda on blacks. Reporting on a Fellowship Commission meeting that he attended covertly, the Overbrook association president told the homeowners’ groups that the “colored” people at the meeting “did not seem to be at all interested in housing [but] the ‘Fellowship Boys’ got up and agitated these people by saying to them that they had the right to move in to any street or any neighborhood in Philadelphia they wanted to.”33 The Overbrook president advised the association members: “You see that these Fellowship people are fellowship for them only—no fellowship for everybody.”34

The homeowners associations also accused the Fellowship Commission of being involved in a “sinister conspiracy” with real estate agents who had reportedly convinced white homeowners to sell their houses to blacks, thereby “blockbusting” all-white neighborhoods. There is no evidence that the Fellowship Commission and real estate agents worked in concert, and, in fact, real estate brokers played a much larger role than the Commission in helping black families move into formerly all-white neighborhoods. Real estate agents had complex motives, but, in almost every case, racially changing neighborhoods presented brokers with substantial economic opportunities. Blockbusting real estate brokers looked for, and sometimes fostered, panic in racially changing neighborhoods and bought homes at below-market prices from panicked white sellers. They then placed advertisements in black newspapers touting these new homeownership opportunities.35 The Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s largest black newspaper, ran several such advertisements every week during the early and mid-1950s. A real estate advertisement from 1952, for example, advised readers to “Go West Young Man. Come to West Philadelphia.” Another realty company promised that “we will secure homes for you in any neighborhood desired,” while a company billing itself as “Phila.’s Most Progressive Office” listed different “West Phila. Specials” on a weekly basis.36 These homes usually sold at a markup to black buyers looking for good quality homes. While these agents helped expand homeownership opportunities for the city’s black residents, they also accelerated the tensions in racially changing neighborhoods like West Philadelphia, and many brokers made significant sums of money in the process.37 For the white homeowners’ groups, both blockbusting real estate agents and the Fellowship Commission represented outside agitators threatening the racial identity of their neighborhoods.

Since the CHR lacked the ability to prosecute cases of housing discrimination, the Fellowship Commission took a different approach. The Commission believed that the best options were simultaneously to try both to win the ACA over by persuading it that its actions would only foster panic selling and to isolate the group by planning meetings and events to improve relations in the racially changing neighborhoods of West Philadelphia. The Fellowship Commission and its West Philadelphia chapter worked with the CHR and local Baptist and Catholic clergy to reach out to the homeowners’ groups. A flier for the Fellowship Commission’s first outreach meeting in 1954, under the headline “Let’s All Pull Together,” invited residents to talk “facts about West Philadelphia” concerning “money, people and houses for sale.”38 Illustrating the strength of the Commission’s relationships with the city’s Democratic Party, the city’s district attorney and future mayor Richardson Dilworth spoke at the meeting. Fellowship Commission executive director Maurice Fagan also met with the ACA president privately, advising him that the Commission was concerned with the rights of religious and nationality groups as well as those of racial groups.39 Fagan further told the ACA that the Commission would not object to “open and above board” civic associations. These efforts to influence the attitudes of white homeowners prefigured the CHR’s 1958 series of “What to Do” kits that were distributed to residents in racially changing communities. Aimed at local leaders in areas like West Philadelphia, the “What to Do” folders included suggestions for local leaders on how to organize and conduct meetings to discuss the importance of communities working together to avoid panic selling and to ensure fair-housing practices. While the CHR distributed the kits widely in an attempt to meet the scale of racial change in the neighborhood, they did not lead to a substantial decrease in reports of community tensions over housing.40

In addition to these outreach efforts, the Fellowship Commission also sponsored neighborhood seminars to encourage community involvement in intergroup relations. Foremost among these efforts, the Commission worked with principals, teachers, and home and school associations to plan inter-playground fellowship events at the elementary schools in West Philadelphia.41 These events were well attended and well received by many black and white parents and children in the area. The Fellowship Commission’s efforts appear to have limited the growth of the ACA past 1955. Racial tensions in other West Philadelphia neighborhoods and other parts of the city, however, overwhelmed the Fellowship Commission’s resources.42 In his evaluation of the Commission’s work in 1955, Fagan asserted:

New problems are developing faster than old ones are being solved because of the emphasis on cases instead of causes. With only 35 full-time workers in the entire city of Philadelphia, it is not possible … to do more than move from crisis to crisis, neighborhood to neighborhood, without staying put long enough to make an enduring difference.43

As Fagan noted, the depth of white resistance to racial integration overwhelmed the Fellowship Commission’s educational strategy.

On the legislative front, the Fellowship Commission played an important role in passing the state’s fair-housing bill, which was enacted in 1961. The Commission lobbied the forty-two member groups of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights Council to advance a narrow bill that covered new housing and housing transactions receiving government assistance, but excluded sales of owner-occupied homes such as those frequently purchased by blacks in racially changing urban neighborhoods.44 While the Commission’s fair-housing bill made political sense in an effort to get legislation through the Republican-controlled state senate, the bill’s exemptions aligned with the view of property rights being advocated by the white homeowners’ groups and weakened the credibility of the Commission’s approach to civil rights.

The magnitude of the challenges facing the Fellowship Commission and other fair-housing advocates, however, was immense. Discriminatory federal housing policy and the business practices of the real estate industry blocked black families from most new suburban construction and managed the racial turnover of urban neighborhoods. Mortgage redlining treated black neighborhoods and black homeowners as investment risks, and this lack of access to credit limited the efficacy of open occupancy or fair-housing legislation for many African Americans.45 Combining with these factors, white homeowners’ groups and civic associations policed the boundaries of segregated neighborhoods and demonstrated what James Wolfinger calls “the limits imposed on liberalism from below.”46 In many cities and states, this resistance to integrated housing coalesced into organized opposition to fair-housing legislation. Most notably, in the 1964 election 65 percent of California voters approved Proposition 14, which sought to nullify the Rumford Fair Housing Act (the state Supreme Court declared Proposition 14 unconstitutional in 1966). As with the Angora Civic Association, supporters of Proposition 14, such as future California governor and U.S. president Ronald Reagan, portrayed fair-housing legislation as “forced housing” and as “an infringement of one of our basic individual rights.”47 As historian Robert Self shows in his study of Oakland, this language of property rights appealed to a large cross section of white voters. “The numbers suggest that the resistance to desegregation in Oakland did not come solely from an antiliberal white working class,” Self argues, “but arose equally among middle- and upper-class whites who understood property rights as sacrosanct expressions of their personal freedom and had little daily contact with African Americans.”48 Similarly, historian Phil Ethington notes that in Los Angeles, the white neighborhoods most geographically isolated from black communities were more likely to vote to repeal fair-housing legislation.49 While anti-fair-housing legislation did not become a ballot issue in Pennsylvania, a 1965 survey of residents in Philadelphia suburbs found that over 70 percent considered “keeping undesirables out” to be a very important objective for local government, rating it well ahead of “maintaining improved public services,” “providing aesthetic amenities,” and “acquiring business and industry.”50 Attempts to pass fair-housing legislation at the federal level also encountered significant resistance. President Lyndon Johnson’s aide later recalled that when Johnson first tried to push a national fair-housing bill through Congress in 1966, for example, the bill “prompted some of the most vicious mail LBJ received on any subject.”51 When Congress finally passed the 1968 Fair Housing Act in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the bill’s weak enforcement provisions did little to curb housing discrimination.52

Sociologist Jill Quadagno summarizes opposition to fair-housing legislation simply, arguing that “for many white Americans, property rights superseded civil rights.”53 White mobilization for segregated neighborhoods, in combination with discriminatory federal housing policy, the business practices of the real estate industry, and the shortcomings of local and federal antidiscrimination policies in housing, made residential segregation the norm in cities and suburbs around the nation. As chapters 3 and 4 demonstrate, defenders of housing segregation laid the foundation for de facto school segregation. This residential segregation emerged from and reinforced a belief that a neighborhood’s racial composition and property values were intertwined and mutually constitutive. This way of viewing space informed everyday encounters across the United States, and in Philadelphia it motivated white homeowners’ groups like the Angora Civic Association to fight for segregation. This group was part of a larger national story, but it also reflected and influenced racial attitudes locally, in Bandstand’s backyard.

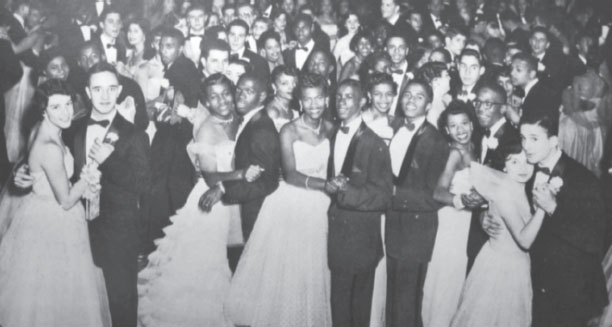

These everyday fights over segregation were not confined to housing. For the teens who appeared on Bandstand and for those who watched the program on television, different levels of racial integration and segregation were part of their daily experiences in youth spaces such as schools, parties, snack counters, and roller rinks. As more black families moved into previously all-white neighborhoods in West Philadelphia, for example, some youth spaces became integrated by virtue of the racially mixed neighborhoods in which they were located. At West Philadelphia High School (WPHS), black enrollment grew from 10 percent in 1945 to 30 percent in 1951.54 Black students held leadership roles in the school, including class president, received class honors in the school yearbook (e.g., most popular, most likely to succeed, peppiest), attended school dances, and participated on the boys’ track, basketball, and swimming teams; the girls’ sports club; and the school newspaper.55 Despite these signs of inclusion in the social life of the school, black students also encountered the anxieties of parents, teachers, administrators, and students who associated their presence with racially changing neighborhoods. In 1951, for example, George Montgomery, the newly appointed principal at WPHS, singled out working-class black students in an assembly after an incident in the school. The Philadelphia Tribune quoted Montgomery as telling the students: “Negroes have become more conspicuous in Philadelphia. There are [a] few intelligent Negroes in the city, there are some fine colored children. However, if you choose to class yourself with them, then it is up to you to go home and ask your parents to which class they prefer you to belong to, the lower or upper class of colored people.”56 Class differences among the black students at West Philadelphia, specifically the entrance of working-class students from the “black bottom” neighborhood, motivated at least some of this racial anxiety. Walter Palmer, who lived in the “black bottom” and graduated from West Philadelphia in 1953, recalled that most of his black and white classmates lived in the more prosperous “top” or western part of West Philadelphia. “We dressed differently, talked, walked, danced, and fought differently,” Palmer remembered. “They were folks with better resources. They tolerated people like myself because they needed me to protect them outside of the school. We didn’t get invited to their parties. We would invite them to ours, but they would be too afraid to come.”57 While it was far from a model of racial equality, in the early 1950s WPHS was among the only high schools in the city that were neither 90 percent white nor 90 percent black (90 percent being the percentage the city’s civil rights leaders would later use to define segregated schools).

FIGURE 3. Teens dancing at prom at West Philadelphia High School. Located three blocks from WFIL’s studio, West Philadelphia High School was racially integrated when Bandstand debuted. West Philadelphia High School Record, 1953. West Philadelphia High School Archives.

Outside of school, informal youth gatherings at house parties and snack shops offered the possibility of interracial association. Dances in the small basements of row houses were a frequent social outlet for teens in West Philadelphia. Weldon McDougal, who grew up in a subdivided house on 48th and Westminster Avenue, in what he called the “top part” (or northwest side) of the “black bottom” neighborhood, remembered:

In the neighborhoods, this is how it worked. I lived at 48th street. Somebody would say, “hey man, there’s a dance on at Shirley’s house tomorrow.” On the way to Shirley’s house which is maybe two blocks away, you could hear a party going on in another basement. So you go down there, and you know there some kids there dancing and having a good time. Well, anybody could come down there. And like I said, we lived next door to white guys and everything so they would come to the dances.

Between twenty and fifty teenagers, mostly black but some Italian and Irish teens from the neighborhood, squeezed into these basements to dance to their favorite R&B songs, and whatever other 45s they brought to the party. McDougall recalls that there were five or six of these local dances every Friday and Saturday in his West Philadelphia neighborhood.58

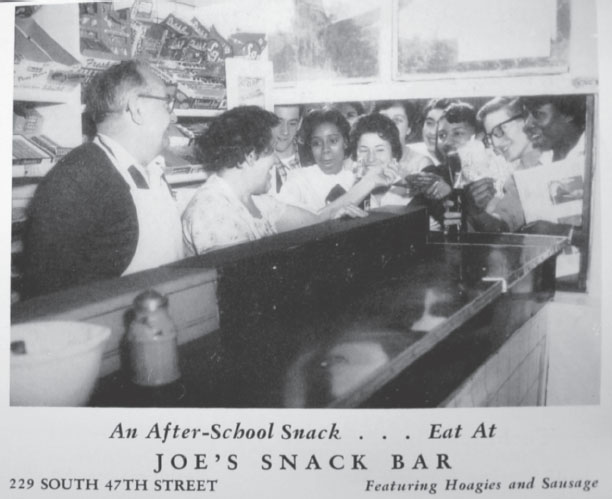

FIGURE 4. From 1954 to 1960, the proprietors of Joe’s Snack Bar placed ads in West Philadelphia High School yearbooks featuring an integrated group of students from the school. West Philadelphia High School Record, 1955. West Philadelphia High School Archives.

In addition to weekend dances, young people hung out at a variety of lunch counters, soda fountains, and ice cream parlors in West Philadelphia. While historical evidence of the racial climate of these establishments is difficult to ascertain and surely varied based on proprietor and clientele, at least one attempted to welcome both black and white teenage customers. Joe’s Snack Bar, located across the street from the West Philadelphia High School, placed advertisements in the school’s yearbook every year from 1954 to 1960.59 These ads stand out from those of the other shops and services that advertised to West Philadelphia students and their parents because every Joe’s Snack Bar ad pictured the proprietors, a middle-aged white couple, happily serving an interracial group of students.

In contrast to the opportunities for casual and friendly interracial interactions at WPHS, basement parties, and some snack shops, other youth spaces were segregated by policy or by custom. Many popular social and recreational spaces used by young people, such as roller skating rinks, bowling alleys, and swimming pools, had segregated admissions practices that flouted the city’s antidiscrimination policies. The Adelphia Skating Rink in West Philadelphia on 39th and Market Street, for example, operated as a club that required teens to be sponsored by members in order to be admitted. Using this policy, the rink’s manager turned away any potential customers he deemed undesirable, including all black teenagers.60 The discriminatory practices at the Adelphia, as well as at rinks in other sections of the city, drew the attention of the local branches of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Working in cooperation with adult members of the ACLU and NAACP, the teenage members of the Fellowship Club formed interracial teams to test the policies of the city’s rinks. With the help of Fellowship Club’s volunteer investigators, the ACLU and NAACP brought the skating rink issue to the Commission on Human Relations (CHR).

In spring of 1953, after receiving reports of discrimination at skating rinks, CHR officials met with the owners of Imperial and Adelphia, as well as four other rinks. The CHR secured written agreements from all of the rink owners to operate in accordance with the city’s antidiscrimination policies.61 Despite these agreements, when mixed groups of skaters from the Fellowship Club tested the rinks’ policies, they continued to find evidence of racially exclusive signs and membership practices, and of managers encouraging segregated patronage. In further defiance of the city’s antidiscrimination policies, rink operator Joe Toppi called the CHR before he opened the Imperial skating rink in West Philadelphia on 60th and Walnut Street to ask permission to operate the rink on a segregated basis. After being informed that this would be illegal, Toppi said he would not exclude anyone, but that he would do everything he could to influence white and black teens to come on different nights. With the rink set to open in early September 1953, Toppi posted signs at the rink and distributed fliers in West Philadelphia and South Philadelphia publicizing three “white nights” and three “sepia nights” a week. This practice immediately drew criticism from the black community in West Philadelphia, and on September 17 a group of black teenagers from the NAACP youth council picketed the rink.62 This same group of teens gained admission on one of the white nights and reported that the white skaters were friendly and that no incidents occurred. Despite the efforts of these black teens, Toppi kept his signs up and continued encouraging white teens to skate on white nights and black teens to come on sepia nights until at least the following year.63

The strongest remedial powers at the CHR’s disposal were public hearings, which it used for the first time in the skating rink discrimination cases. In the internal meeting where it decided to use public hearings, the CHR identified three purposes: First, it would give “the respondent an extra chance to comply before taking him to trial.” Second, it would have a “good psychological effect [and] both the respondent and complainant would be more impressed by the power of the CHR.” And third, the “hearing could be of tremendous community value.” Whereas the CHR lacked the power to address many facets of discrimination in the city, it believed these youth cases would “strengthen the CHR” and show that the group was “coming of age,” without forcing the group to test its authority by confronting the school board or business interests as it would in large-scale education or employment cases.64 In May 1954, the CHR held public hearings charging the proprietors of two skating rinks in Northeast Philadelphia of failing to comply with city and state laws prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations or recreation. The CHR reached a settlement calling for the rinks to stop using membership cards and other discriminatory membership practices, and to post signs stating the new nondiscriminatory admissions policies.65 While the agreement reduced the discriminatory practices at most rinks and the CHR did not hear another skating rink case, the Fellowship Club volunteers continued to find evidence of segregation at skating rinks and bowling alleys through the late 1950s.66

The CHR’s public hearings on discrimination at skating rinks came just days before the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the first Brown decision on May 17, 1954, outlawing de jure racial segregation in education. Although the decision applied only to the southern and midwestern states in which schools were segregated by law, many civil rights advocates in Philadelphia expressed optimism that the decisions would force the city to address the de facto racial segregation of its schools. As chapters 3 and 4 demonstrate, however, the school board’s independence from the city government insulated the schools from CHR investigations. The CHR’s inability to check housing discrimination or address school segregation made small victories like the skating rink cases all the more important. Yet despite its attention to integration in these youth spaces, the CHR was wholly ineffective when faced with the segregation of Bandstand, the most visible youth space in Philadelphia. If the housing fights in Bandstand’s backyard of West Philadelphia were about the physical proximity of people of different races as neighbors, the struggles over segregation on Bandstand were about the potential for teenage social interactions, and televisual representations of these meetings, to disturb anti-integration sentiments among the viewing public.

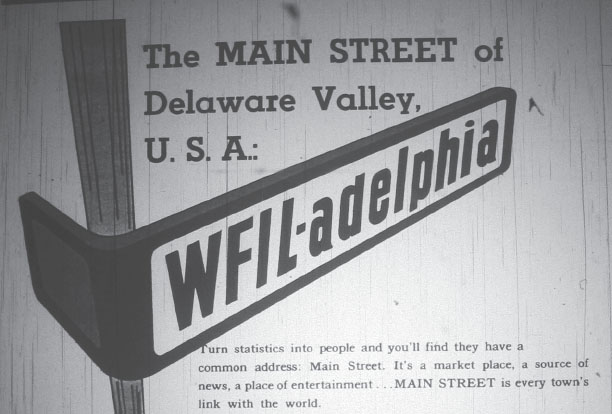

Broadcasting from West Philadelphia, WFIL could not ignore the battles over segregation taking place around its studio and across the city. The station, however, had a vested interest in not presenting visual evidence of these local fights to its regional viewers. Like the Angora Civic Association, WFIL viewed the station’s neighborhood through the lenses of property values and race. Yet while the homeowners’ groups fought over individual houses and blocks, WFIL’s calculations included millions of homes in the Philadelphia region and the advertisers eager to reach this lucrative market. This meant that WFIL courted viewers not only in Philadelphia and the growing suburban counties outside of the city, but also those across a four-state broadcast region that included parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. The station called this area “WFIL–adelphia,” and in the early 1950s the station made this phrase the centerpiece of its marketing campaign. Radio and television broadcast signals, of course, do not conform to the geographic or political boundaries of cities, so WFIL was not unique in having a regional audience. WFIL’s use of WFIL–adelphia to bring the station, city, and region together under one brand name, however, illuminates the station’s approach to early television and is essential to understanding how Bandstand became segregated.

The WFIL–adelphia moniker was part of a larger campaign by Walter Annenberg’s Triangle Publications to promote the Delaware Valley as a center for business and industry. In October 1952, the Philadelphia Inquirer (owned by Annenberg) featured an eighty-page pullout magazine on the growth and promise of “Delaware Valley, U.S.A.” Aimed at the business community, the magazine’s inside cover thanked more than eighty companies for their advertising support. The report, extolling the virtues of the Delaware Valley port and the region’s “steel, oil, textile, auto manufacturing, electronic, and chemical” industries, recalled the nineteenth-century boosterism that helped draw industries to midwestern hubs like St. Louis and Chicago.67 A full-page world map, for example, illustrated how “raw materials from at least 75 foreign countries funneled into Delaware Valley” port facilities, including cocoa beans and iron ore from Nigeria, marble from Italy, and lumber from Brazil. All routes on the map lead back to the Delaware Valley, the only site labeled in the United States. A large circle marks the region, covering the entire Eastern Seaboard.68

FIGURE 5. WFIL pitched the station to potential advertisers as the best way to reach viewers not just in Philadelphia but across the Delaware Valley. October 13, 1952. Used with permission of Philadelphia Inquirer.

While the Delaware Valley-centric worldview was undoubtedly exaggerated, promoting the Delaware Valley as a place of “amazing, breathless growth” and the “greatest industrial area of the world” also helped to promote the value of Annenberg’s media properties in the region.69 Indeed, two full-page advertisements described WFIL as the best way to connect people and potential customer across the Delaware Valley (or WFIL–adelphia) region. WFIL promised advertisers that the television station would bring them “5,869,284 customers” across a “27-county area.” The ads described these viewers in explicitly monetary terms: “Advertisers … there’s $6 Billions [sic] waiting for you in WFIL–adelphia. SELL ALL of America’s 3rd market on WFIL–TV. You can really go to town—to hundreds of towns in the rich Philadelphia market—on WFIL–TV … Get the most for your money, the most people for your money. Schedule WFIL-TV.”70 West Philadelphia may have been the station’s physical home, but this vast regional WFIL–adelphia consumer market was what WFIL sold to Bandstand’s advertisers.

FIGURE 6. The WFIL–adelphia broadcast market included parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Mary land. October 13, 1952. Used with permission of Philadelphia Inquirer.

These ads also cast WFIL–adelphia as the new “Main Street of Delaware Valley, U.S.A.”:

Turn statistics into people and you’ll find they have a common address: Main Street. … MAIN STREET is every town’s link to the world. Today, thanks to electronic science, Main Street goes to the people. And from curb to curb of the Philadelphia Retail Trading area, the busiest Main Street is WFIL–adelphia. The population of this trading zone, as well as a vast area beyond, lives, works and shops in WFIL–adelphia. WFIL–adelphia is a market place—where America’s leading advertisers sell their wares, via WFIL–TV.71

In describing WFIL–adelphia in this way, the ads reenvisioned the “resonant and symbolic location” of Main Street.72 Historian Alison Isenberg has described how “varied downtown investors endeavored to make their own markets and to chart Main Street’s future in order to protect and enhance their stakes.”73 Isenberg notes how local newspapers and regional news companies, like Annenberg’s Philadelphia Inquirer and WFIL radio and television stations, had a vested interested in bolstering Main Street’s advertising value and frequently sponsored the Main Street postcards that were ubiquitous in the early twentieth century.74 “The ‘place’ … illuminated in the postcards was not a brick-and-mortar location,” Isenberg writes, “but rather a territory within Americans’ imaginations, a hopeful vision of urban commerce transformed.”75 WFIL’s ads imagined the place of Main Street in similar ways. The ads did not make reference to a physical Main Street, but rather to the “5,869,284 customers” in homes dispersed across a “27-county area.” With WFIL–adelphia, WFIL promised to use broadcast technology to further transform urban and regional commerce. If Philadelphia could no longer connect businesses, advertisers, and customers on Main Street, WFIL–adelphia would provide this safe and prosperous commercial space. (Disneyland, of course, also made use of this Main Street ideal to promote a suburban and racially homogenous alternative to urban and multiracial commercial spaces when it opened in 1955.)76

While not mentioned in the ads, the WFIL–adelphia viewers that WFIL promoted to advertisers lived in states that supported racial segregation by both law and custom. Both Maryland and Delaware maintained de jure segregated school systems until the Brown decisions and resisted court-ordered desegregation for another decade thereafter.77 Interracial marriage was also illegal in both states until Loving v. Virginia in 1967.78 For a station pitching itself as a regional Main Street, the existence of legal segregation in its broadcasting area offered a significant financial incentive to not upset anti-integration sentiment among viewers and advertisers. At the same time, the segregated housing policies in Pennsylvania suburbs also contributed to WFIL’s understanding of WFIL–adelphia. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s pullout magazine on the Delaware Valley offered pictures and glowing profiles of housing developments under construction in Levittown and Fairness Hills, Pennsylvania, as evidence that the region was “booming.”79 These neighboring Bucks County developments had policies that prevented blacks from buying homes, making Levit-town and Fairness Hills what Charles Abrams termed “closed cities.”80 While WFIL–adelphia attempted to reconstitute Main Street in an era of suburbanization, the decision to profile Levittown and Fairness Hills as exemplars of the Delaware Valley reemphasized that WFIL–adelphia would privilege the desires and attitudes of white suburban consumers.

In this way, WFIL–adelphia offers an example of how television helped reorganize urban and suburban spaces. As media studies scholar Lynn Spigel has suggested, many postwar commentators argued that television “would allow people to travel from their homes while remaining untouched by the actual social contexts to which they imaginatively ventured.” Television could act as a space-binding tool to promote public culture among viewers living in detached single-family suburban homes, while also keeping “undesirable” people and topics out of the home. Spigel calls this a “fantasy of antiseptic electrical space.”81 WFIL–adelphia promised a version of “antiseptic electrical space” to both viewers and advertisers. To viewers, it offered the ideal of Main Street without upsetting their anti-integrationist attitudes. To advertisers, it offered access to a growing market of suburban consumers with disposable income. All the while, WFIL still needed Philadelphia—the economies of scale it provided, the size of its population, and the creative energies of its people—in order to promote WFIL–adelphia. The best place to see how WFIL navigated the conflicting demands of WFIL–adelphia is the show that became the station’s most popular locally produced program, Bandstand.

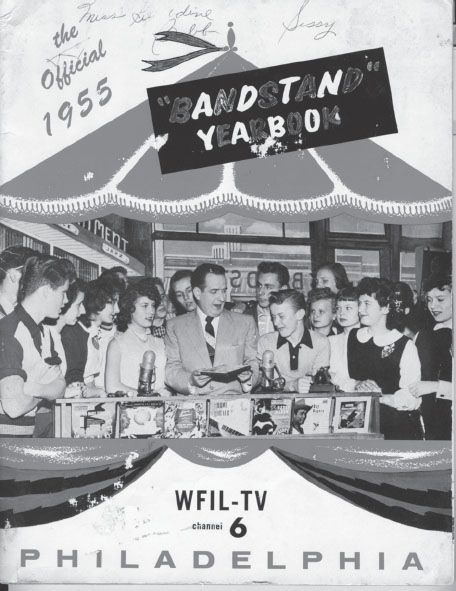

From its debut, Bandstand’s producers looked beyond Philadelphia to the potential profits available from advertisers and record companies eager to reach the largest possible television audience. In doing so they carved out a new position for a local television program in relation to the radio and record industries at a time when all three industries were undergoing significant changes. Bandstand debuted in a pivotal year in television’s development into a national medium. Between 1948 and 1952, the number of television sets increased from 1.2 million to 15 million, and the percentage of homes with television increased from 0.4 percent to 34 percent.82 More important, in April 1952 the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) lifted its freeze on television licenses, ending a four-year block on new licenses and making more frequency assignments available to a larger number of metropolitan areas. Over the next three years, the number of television stations in operation increased from 108 in 1952 to 458 in 1955. By 1955, the most populous cities each had between three and seven stations, and the FCC believed that 90 percent of the nation’s population lived in the broadcast range of at least two stations.83

Media consolidation increased as the FCC allocated new television licenses. Newspapers owned 69 percent of TV licenses in 1953, up from 33 percent when the freeze started in 1948. Multiple ownership also became much more common in television than in radio, where newspapers owned 20 percent and 32 percent of AM and FM radio stations, respectively, in 1953.84 The FCC’s decision to allow newspaper-television cross-ownership helped to ensure that television, like radio before it, would follow the commercial advertising model. With an increased number of potential viewers and a limited number of new licenses, VHF TV stations were extremely valuable. Lobbying FCC commissioners became commonplace, and newspapers were among the applicants most capable of assuring favorable licensing decisions.85 Triangle Publications, owned by Walter Annenberg, who had inherited the Philadelphia Inquirer from his father in 1942 and had purchased WFIL radio in 1945, was among the media conglomerates to add a television station in 1948. Annenberg described the reasoning that pushed him into television to his biographer in 1996:

I was willing to gamble that [WFIL–TV] wouldn’t lose that much money. And it didn’t cost me much. It operated in the red for only six months. But my instinct told me this was an opportunity. How could it fail? WFIL had authorization for television [grandfathered in by the FCC] and I knew Philadelphia was going to be entitled to three stations. I would have one of three in an area that served more than five million people. I knew the advertising potential. It had to be a bonanza!86

As Annenberg liked to say, acquiring a television station only cost him a “three-cent stamp” to mail the license application, so the ratio of risk to reward was decidedly in his favor.87 Annenberg expanded his investment in television by acquiring television magazines in several major cities and starting TV Guide in 1953. TV Guide combined television listings tailored to specific local markets with a wraparound national edition promoting television shows and personalities.88 By 1959, Annenberg’s Triangle Publications also owned television stations in Binghamton, New York; Altoona-Johnstown, Pennsylvania; Hartford-New Haven, Connecticut; Lancaster-Lebanon, Pennsylvania; and Fresno, California.89 For Bandstand, Annenberg’s media empire provided advertising connections and expertise that helped to launch the show.

Through the early and mid-1950s, the increase in the number of channels expanded the total amount of airtime that stations needed to fill and left stations looking for profitable shows to broadcast in the daytime hours, when networks supplied affiliates with little if any programming. Like many other stations in the early 1950s, Philadelphia’s WFIL filled its afternoon schedule with old movies, since ABC offered its affiliates no daytime programming and Hollywood leased only outdated movies to the perceived rival medium. These movies flopped, leaving WFIL with an afternoon slot to fill. Roger Clipp, the station’s general manager, asked disc jockey Bob Horn to host an interview show, interspersed with filmed music shorts that had been collecting dust in WFIL’s archives.90 Horn already hosted a radio Bandstand program at WFIL; although his radio program was successful, like a number of prominent national radio personalities, he wanted to move from radio to television.91 Radio comedians like Fred Allen, Milton Berle, Jack Benny, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Sid Caesar, and Bob Hope all moved to television in the early 1950s. Television networks viewed these radio personalities as established talent that would help the fledgling medium attract large national audiences and lucrative sponsors. In many cases, popular variety shows and sitcom programs were simply picked up from radio and reworked for television.92 Like the national networks that signed these radio stars, WFIL viewed Horn as a dependable radio personality, and like these more widely known comedians, Horn viewed television as an exciting and potentially profitable endeavor.

The first televised version of Horn’s Bandstand debuted in September 1952. Jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie, a friend of Horn’s who happened to be in town, was the guest. Horn chatted with Gillespie for a few minutes about his current recordings and tour. Horn then turned to the camera to announce a film of Peggy Lee singing “Mañana.” Subsequent shows continued in the same way, moving between Horn’s interviews with whatever guests he could find and the films.93 Despite Horn’s talents as a disc jockey, this format proved unsuccessful. Determined to hold his television slot, Horn met with Clipp and station manager George Koehler and proposed to bring in a studio audience of teenagers and make their dancing the focal point of the program. Horn looked to Philadelphia’s 950 Club (1946–55), where radio hosts Joe Grady and Ed Hurst invited local high school students to come to the show’s center city studio and dance to the records they broadcast on their program.94 Horn combined this successful format with the name of his own successful radio show, Bandstand. WFIL’s Clipp and Koehler gave Bandstand a second chance because the station wanted to add a show with low production costs that would attract teenagers, and the advertisers eager to reach teens, to WFIL’s afternoon television lineup.95

Tony Mammarella, a talented producer at WFIL, joined Horn in readying Bandstand for its debut. As Bandstand’s producer, Mammarella prepared the set, managed the admission of the studio audience, acted as a liaison between sponsors and Horn, and served as an occasional cameraman and stand-in host. Working with a modest budget, Mammarella devised a set that looked like the inside of a record store using a painted canvas backdrop and a mock-up sales counter. Banners from neighborhood high schools hung on a canvas next to the record store set, and Mammarella installed wood bleachers at one side of the studio for seating. With a studio designed to resemble two teenage spaces—the record shop and the high school gymnasium—Horn’s television Bandstand premiered on October 6, 1952, as a daily program broadcast in the Philadelphia area from 3:30 to 4:45 P.M.96

Thanks to a three-week promotional campaign and the proximity of three high schools—West Catholic High for Girls, West Catholic High for Boys, and West Philadelphia High—Bandstand had no trouble filling the studio to its two-hundred-person capacity. Only two blocks from the studio, the predominately Irish and Italian teenage girls who attended West Catholic High for Girls became the most consistent visitors to Bandstand. Teenage boys from West Catholic High for Boys were nearly as close, as were boys and girls from West Philadelphia High School, a public school that enrolled mostly Jewish and black students. Teens from other schools and neighborhoods also visited Bandstand shortly after its debut, and teens from South and Southwest Philadelphia became some of the most visible stars of the program.

The production format Horn and Mammarella established in Bandstand’s first days remained largely unchanged during Bandstand’s local years. During the broadcasts, Horn introduced records, and the cameras focused on the teenagers dancing. At the midway point in the show, Horn yelled “We’ve got company” and introduced that day’s musical guest, who would lip-sync his or her latest record.97 On its first day, as it would in its first two years, Bandstand featured music primarily from white pop singers such as Joni James, Georgia Gibbs, Frankie Laine, Connie Boswell, and Helen O’Connell. In an era before black rhythm and blues crossed over to mainstream white audiences, and “rock and roll” was not yet a household term, this selection of artists reflected what most radio stations played. Jerry Blavat, who became a regular on Bandstand and went on to become an R&B deejay in the Philadelphia area, remembers being exposed to both white pop music and black R&B as a teenager in an Italian section of South Philadelphia:

When I was a kid at 12 or 13 years old, I lived in a neighborhood where there was always music. And I would hear my aunts and my uncles playing the Four Aces, the Four Lads, Frankie Laine, and Rosemary Clooney. And then all of the sudden I turned on a television show in 1952 and I see kids dancing to this music. But I also hear rhythm and blues. “Sh-Boom” by the Chords and “Little Darling” by in those days the Gladiolas, before “Little Darling” was remade by the Crew Cuts. And this music hit my ear even though I was listening to my aunts and uncles play the pop music of the day.98

While hip teenagers like Blavat were becoming familiar with R&B through jukeboxes and records, Bandstand’s white pop songs proved popular with many of the city’s young people. By the show’s first anniversary, Bandstand fan club membership neared ten thousand local teenagers, and the Philadelphia edition of TV Guide praised the show as “the people’s choice” (both Bandstand and TV Guide, of course, were part of Annenberg’s Triangle Publications).99 In outlying neighborhoods, where young people could not make it to the show’s studio, Bandstand annexes were set up in fire houses and other public buildings where teenagers gathered to watch the show on TV and dance. By the start of 1955, the show was the top-rated local program in its time slot, and tens of thousands of teenagers had attended a Bandstand show at WFIL’s studio.100

The teenagers who visited Bandstand came not only from Philadelphia, but also from across the wider WFIL–adelphia area. Pennants along the studio wall featuring the names of high schools and towns outside of Philadelphia reminded television viewers (and advertisers) of Bandstand’s geographic scope, as did a daily roll call during which teens in the studio audience gave their names and high schools. The show also featured a character called Major Max Power (a man dressed in a dark military-styled uniform with a large MP on his chest) who appeared weekly to tell host Bob Horn (and the studio and television audiences) about new viewers seeing the program.101 With each of these features, Bandstand made reference to the WFIL–adelphia market and to the show’s ability to deliver a large regional viewing audience to advertisers.

Although Bandstand was not always on the cutting edge of new music, Philadelphia was a “breakout” city where producers would test records before distributing them nationally. Producers looked to Philadelphia because of its proximity to New York, where many of the record companies were located, and because it was the third largest city in the United States in the early 1950s, with more residents than St. Louis and Boston combined. Philadelphia’s racial and ethnic makeup also made the city a productive place to test new music and find musical talent. The city’s black and Italian residents lived in close proximity in many neighborhoods, and despite significant tensions over housing and education, musical styles and tastes often overlapped. These interracial music exchanges made Philadelphia a thriving market in which to test new R&B and rock and roll music.102

FIGURE 7. Bob Horn, the original host of Bandstand, interviews audience members during the daily roll call. This segment, along with the pennants displayed in the background, reminded viewers of the show’s large regional audience. The Official 1955 Bandstand Yearbook.

From its earliest days, Bandstand’s producers viewed the show as a regional program with the potential, given Philadelphia’s clout as a test market, to influence the music played on pop radio stations across the country. The decentralization of the recording and radio industries made the show even more valuable as a platform for artists and record labels to reach larger audiences. Through the 1950s, a number of small record labels and local radio stations emerged to challenge the major record firm oligopolies and national radio networks. This decentralization occurred for four reasons. First, in 1947 the FCC approved a large backlog of applications for new radio stations. As a result, many independent stations emerged, doubling the number of radio stations in most markets. Second, the advent of smaller, lighter, and more durable 45 rpm records (as opposed to delicate 78s) made it possible for smaller companies to ship records across the country. Third, after television took much of the entertainment talent and national advertising spending away from radio, radio stations focused on local markets and turned to records as inexpensive forms of programming. And finally, these smaller record firms and radio stations thrived by marketing to distinct segments of the audience, including the teenage market that grew in size, had more access to music through cheap and compact transistor radios, and gained recognition among marketers through the 1950s.103

Taken together, these changes profoundly affected the range of music available to consumers via records and radio. For example, the four largest record firms—RCA, Columbia (CBS), Capitol, and American Decca (MCA)—held an 81 percent market share of hit records in 1948, but by 1959 this share declined to 34 percent. The four radio networks (CBS, NBC, ABC, and Mutual Broadcasting System) that vied for a share of the total national radio audience in 1948 gave way to more than one hundred autonomous local markets by the end of the 1950s.104 Many of these radio stations followed the network standard and programmed news alongside vocal and orchestral popular music. A smaller number of stations looked for attention-catching records that would attract teenage listeners. These radio stations turned to the recently founded companies that recorded R&B rather than the big band swing and crooners still favored by the major labels. These stations first emerged in cities with sizable black populations, like Philadelphia’s black-oriented WHAT-AM, and there were at least fifty other R&B stations across the country by 1960.105

Compared to these radio stations, Bandstand was conservative in its musical selection. While Bandstand sampled watered-down covers of black R&B records by white artists in the early 1950s, radio shows in other cities introduced teenagers to a variety of original R&B records. While these radio R&B shows caused some controversy, radio continued to have more freedom than television to play new music by black artists because the stations broadcast later at night and did not feature visual images. Foremost among these radio outlets, Memphis’s WDIA, the first radio station programmed by blacks for a black audience, and Alan Freed’s popular Moondog radio show in Cleveland and later New York played original R&B songs produced by small independent record companies.106 Audiences for these radio shows varied based on the demographics of the areas in which they broadcast, but most attracted young people across racial, class, and spatial lines.107

Bandstand was among the first television programs to join these radio broadcasters and record producers as an important promotional platform for music. For example, the Three Chuckles, a white Detroit-based group, drove all the way to Philadelphia to perform on Bandstand in 1953. The group performed “Runaround,” which at the time was a local hit released on Boulevard, a small Detroit label. Fueled by sales of the song in Philadelphia, major label RCA Victor released “Runaround” nationally, and it became a hit in 1954.108 On television’s power as a promotional tool in this era, jazz trumpeter and trombonist Kirby Stone told Down Beat magazine, “We could have knocked around in clubs for 10 years and never have been seen by the number of people who have seen us on television. One night on TV is worth weeks at the Paramount.”109 Even though Bandstand was not yet broadcast nationally, it offered recording artists exposure far beyond the show’s point of origin in West Philadelphia.

With its regional and national influence, Bandstand was at the leading edge of the emerging relationship among television, radio, and the music industry. Bandstand was not the only local television show to create a niche in this changing media landscape, and by 1956 nearly fifty markets had television dance shows similar to Bandstand.110 However, with a broadcast signal that reached parts of four states, positive publicity from Walter Annenberg’s media properties such as the Philadelphia Inquirer and TV Guide, and daily musical guests, Bandstand was the most influential of these locally televised music shows. Before Alan Freed brought his popular radio shows and concerts to television in 1956, and before Ed Sullivan broadcast Bo Diddley in 1955 and Elvis Presley in 1956, Bob Horn’s Bandstand had grown into a local show with national influence, making it the most important television venue in this era for artists and producers looking to reach a large audience. This success, however, came at a price for the black teenagers in the West Philadelphia neighborhood around Bandstand’s studio. While the program started playing black R&B by 1954, the show also implemented admissions policies that had the effect of excluding black teens. While the producers’ racial attitudes may have contributed to these policies, their desire to create a noncontroversial advertiser-friendly show did more to encourage the policies. For Bandstand, reaching teenage consumers across WFIL–adelphia took priority over providing a space that would be open to all teens in its backyard of West Philadelphia.

Over the course of Bandstand’s local production history (September 1952 to July 1957), teens who visited the studio or watched the show experienced it first briefly as an integrated space and later, after changes to the admission policy, as a segregated space. When it started in 1952, Bandstand admitted teenagers on a first-come first-served basis. Weldon McDougal, who attended West Philadelphia High School, remembered that although Bandstand did not yet play the R&B music he liked, he had no trouble getting into the show in 1952 and 1953:

West Philly [High School was] so close to Bandstand. Bandstand used to start at 2:45. West Philadelphia at the time, we used to get out at 2:15. When Bob Horn was there, I’d rush over there and it was first-come first-served. So I’d go in there and dance, until they started playing all of this corny music. Then there weren’t many black guys who would go over there. I was considered corny going over there. I was just seeing what was happening. It wasn’t like I wanted to be on television, because I didn’t care after awhile.111

As the show’s popularity increased, however, Bandstand adopted admission policies that, while not explicitly whites-only, had the effect of discriminating against black teenagers. In 1954, Bandstand selected a group of twelve white teenagers to serve as the show’s “committee.” Committee members enforced the show’s dress code (a jacket or a sweater and tie for boys, and dresses or skirts for girls) and were tasked with maintaining order among the other teens on the show.112 In the Bandstand pecking order, the committee members were followed by studio regulars and by periodic visitors to the show. The committee members exercised considerable sway over who would be admitted on a regular basis, and, by 1954, Bandstand required everyone but the committee members and the regulars to send a letter to WFIL in advance to request admission to the show on a specific day.113 In practice, this admissions policy resembled the discriminatory membership policy of the skating rinks outlined earlier. Teens who gained admission to Bandstand after 1953 did so in one of two ways. Some teens were in the same social peer group as the show’s committee and regulars, who by 1953 came mostly from Italian neighborhoods in South Philadelphia or West Catholic High School (which was predominantly Irish and Italian). Other teenagers had to plan their visits weeks or months in advance and request tickets. This became a common practice for teens who lived in Allentown, Reading, and other cities and towns outside of Philadelphia. These teens became familiar with the show from television and from the record hops in the areas around Philadelphia that Bob Horn hosted with the Bandstand regulars. These areas included growing suburban counties with small black populations, such as Delaware County (7 percent black population in 1950), Montgomery County (4 percent), and Bucks County (less than 2 percent).114 Given that the outlying areas had fewer black residents, the teens who traveled to visit the show were predominately white. For black teens who lived only a few blocks from the studio, the advance notice aspect of the admission policy further marginalized them from the show. As a result of these admissions policies, Bandstand’s audience became almost all-white by the end of 1954.

The admission policies appealed to the producers’ commercial goals for the program. By encouraging teenagers from outside the city to attend the show, Bandstand further established its popularity with WFIL–adelphia. Inviting teens from this regional area to watch the show, request tickets, and write fan letters strengthened Bandstand’s ability to persuade advertisers to sponsor the show. Here again, Bandstand’s producers marketed the program to the largest possible regional audience, appealing to those teens in the four-state broadcast area rather than the local teenagers in Bandstand’s West Philadelphia neighborhood.

Bandstand’s producers also adopted the new admissions policies to minimize the potential for racial tension among teenagers outside the studio. Yet while the producers hoped that distributing admissions passes in advance would make it easier to control the crowd of teenagers, the policy had the opposite effect. It provided black teenagers with an opening to protest their exclusion from the show. West Philadelphia teen Walter Palmer, for example, organized other black teenagers to test the show’s admissions policies. “Bandstand was segregated,” Palmer recalled. “There were white kids from all of the Catholic schools, but no black kids. West Catholic was on 46th, and they were always there; our school [West Philadelphia High School] was on 47th [and we could not go].” After graduating from West Philadelphia High School, Palmer remembered that “I engineered a plan to get membership applications, and gave them Irish, Polish, and Italian last names. They mailed the forms back to our homes and once we had the cards we were able to get in that day.” Palmer’s plan successfully undermined Bandstand’s admission policies, but that day, and other times when black teens attempted to gain admission to the studio, they frequently dealt with violence from white teens. While Palmer recalls that he and his peers from the “black bottom” held their own in these fights, he remembered there were “all-out race riots outside the studio.”115 In their attempts to challenge Bandstand’s racially discriminatory admissions policies, black teens faced verbal and physical harassment that further marked Bandstand as a site restricted to white teenagers.

Concerned that racial tensions would threaten Bandstand’s image as a safe place for teenagers and scare off advertisers, WFIL sought help from the Commission on Human Relations (CHR) to calm the tensions among teenagers waiting in line. A May 1954 CHR case update, titled “WFIL–TV v. Negro and White Teen Agers,” states: “Plans for admittance for teen agers as guests of the Band Stand program have been ineffective and conflicts have arisen principally on the part of those teen agers who could not gain admittance.”116 In other words, Bandstand implemented a racially discriminatory policy, and then asked the city’s antidiscrimination agency to address the resulting protests. The Philadelphia Tribune reported that Horn assured the CHR that “the only preference shown was the case of special out-of-town groups visiting the studio” and that teens “who adhered to the policy of proper dress and conduct were readily admitted, without regard to the race.”117 Nominally nondiscriminatory, this policy gave Bandstand the flexibility to exclude black teenagers. Concerns about the potential for race riots among teens strengthened the producers’ policy of admitting only committee members, regulars, and those who requested cards of admission rather than admitting teens on a first-come first-served basis. A second CHR report on intergroup tensions in recreation facilities in March 1955 makes clear the outcome of this policy:

Police reported that disorderly behavior of teenagers at Bob Horn’s Bandstand program, where the audience participate in the show by social dancing, had resulted in the absence of Negroes from attendance. The management denied having a discriminatory policy, and CHR had little upon which to base a case of discrimination. Observers note a lack of Negro participation.

The report went on to state that young women from the mostly black William Penn High School in North Philadelphia had raised “the question of elimination of Negro youth” from Bandstand, and that the CHR saw a need for “broad planning to effect integration of this activity for high school youth.”118 There is no evidence that the CHR ever undertook such efforts to integrate Bandstand, and available pictures of the show from 1955 and after reveal that the show remained segregated.