Cause they’ll be rockin’ on Bandstand

In Philadelphia P.A.

Deep in the heart of Texas

And ‘round the Frisco bay’

Way out in St. Louis

And down in New Orleans

All the cats wanna dance with

Sweet little sixteen.

— Chuck Berry, “Sweet Little Sixteen,” 1958

It was no accident that Chuck Berry made reference to American Bandstand when he released “Sweet Little Sixteen” in January 1958. Berry made his national television debut on American Bandstand in 1957, and including these lyrics helped ensure that this new song would receive ample airtime on the program. Indeed, Dick Clark later recalled “Sometimes we heard a hit the first time we played the record—Chuck Berry’s ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ was like that.”1 Berry’s song reached number two on the Billboard chart and stayed on the chart for sixteen weeks, thanks in large part to its frequent exposure on Clark’s show. Less obvious than his references to Philadelphia and American Bandstand, Berry’s nods to teens dancing in Texas, San Francisco, St. Louis, and New Orleans underscored a point that American Bandstand called attention to every afternoon—the existence of a national youth culture. As the show sought to establish itself as a national program, it pointed to its local fans and television affiliates in different parts of the country as evidence of its national reach. In helping viewers and advertisers imagine a national youth culture, America Bandstand promoted the idea that teenagers were united in their simultaneous consumption of television and rock and roll. This chapter examines how, through a range of production strategies, American Bandstand encouraged the show’s viewers, advertisers, and television affiliates to see the program as the thread that stitched together different teenagers in different parts of the country into a coherent and recognizable national youth culture.

In exploring how American Bandstand producers articulated this vision of national youth culture, this chapter builds on Josh Kun’s notion of “audiotopia” and Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities.” Kun uses the concept of audiotopia to describe how “music functions like a possible utopia for the listener, that music is experienced not only as sound that goes into our ears and vibrates through our bones but as a space that we can enter into, encounter, move around in, inhabit, be safe in, learn from.”2 American Bandstand adds a visual component to Kun’s formulation. Teenagers tuned into American Bandstand to watch other teenagers dance to records, to see musical artists perform, and to try out the latest dance moves in their own living rooms. American Bandstand’s daily images encouraged teenagers to imagine themselves as part of a national audience enjoying the same music and dances at the same time. American Bandstand offered its viewers a teenage television audiotopia every afternoon. This televised audiotopia was most pronounced for the Italian-American teenagers who were prominently represented on the show. For them, American Bandstand made their neighborhood peer culture an integral and visible component of the national youth culture. The show’s ongoing segregation, examined in the next chapter, makes it clear that this televisual audiotopia was not equally available to all viewers.

American Bandstand also adds a visual component to Anderson’s theory of imagined communities. Anderson highlights newspapers as one of the ways that people first understood (or imagined) themselves as part of a community without face-to-face contact with other members of this community. He describes the “extraordinary mass ceremony” of the “almost precisely simultaneous consumption” of newspapers. The importance of this consumption ritual, Anderson argues, is that

each communicant is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the slightest notion. Furthermore, this ceremony is incessantly repeated at daily or half-daily intervals throughout the calendar. What more vivid figure for the secular, historically clocked, imagined community can be envisioned? At the same time, the newspaper reader, observing exact replicas of his own paper being consumed by his subway, barbershop, or residential neighbours, is continually reassured that the imagined world is visibly rooted in everyday life.3

As was the case with the newspapers in Anderson’s example, teenagers watched American Bandstand simultaneously with little face-to-face knowledge of the millions of other viewers watching the show. Unlike newspapers, however, as a television program American Bandstand visualized this imagined community through its studio audience, viewer letters, and maps, and by consistently addressing its viewers as part of a national audience. As political scientist Diana Mutz notes, “[w]hat media, and national media in particular, do best is to supply us with information about those beyond our personal experiences and contacts, in other words, with impressions of the state of mass collectives.”4 American Bandstand used its production techniques and mode of address to offer teenagers daily evidence that the imagined national youth culture was “visibly rooted in everyday life.” American Bandstand’s popularity and profitability flowed from its ability to get viewers, advertisers, and television affiliates to imagine a national youth culture with the show at the center.

In an era when advertisers “discovered” teenagers, American Bandstand offered daily access to the largest market of young consumers. Almost every minute of American Bandstand was dedicated to selling products. From paid advertisements for consumer goods to promotions of records and musical guests (also often paid for by record promoters), the show presented its viewers with a host of messages every day. The show urged teenagers to drink Seven-Up and Dr. Pepper, snack on Rice-A-Roni and Almond Joy, buy records by the newest hit-makers and carry these records in an American Bandstand case, read about the show’s regulars in publications like ‘Teen magazine, wear the same “Dick Clark American Bandstand” shoes as these dancers, learn new dances from the American Bandstand yearbook, and apply Clearasil to their pimples. This was an extraordinarily high level of promotional activity, even by the standards of commercial television. By representing the show’s teenagers consuming all of these products, American Bandstand constructed a national youth culture centered on simultaneous consumption. By inviting viewers to participate in the same consumption rituals as the studio audience, American Bandstand encouraged teens across the country to identify with each other.

American Bandstand established Philadelphia as the locus of this national youth culture, and it drew extensively from the creative abilities of the city’s youth. Some of these contributions were well documented, others obscured. On the one hand, Italian-American teens figured prominently in the show’s image of youth culture. Many of the show’s regular dancers and local fans hailed from working-class Italian-American neighborhoods, and they later remembered American Bandstand as providing them with unique exposure. On the other hand, the program’s racially discriminatory admissions policies remained in place. With the program broadcasting nationally, black teens were erased not just from the “WFIL–adelphia” regional market, but also from the national youth culture American Bandstand worked to build. While the next chapter examines the struggles over segregation surrounding the program, this chapter shows how American Bandstand became established as the afternoon site of the nation’s youth.

When ABC decided to take Bandstand national in 1957, dozens of local markets already had or would soon start their own teen dance shows. Like Bandstand, programs such as The Milt Grant Show in Washington, D.C., The Buddy Deane Show in Baltimore, High Time in Portland, Oregon, The Clay Cole Show in New York, Dewey Phillips’ Pop Show in Memphis, Clark Race’s Dance Party in Pittsburgh, Robin Seymour and Bill Davies’s Dance Party in Detroit, Phil McClean’s Cleveland Bandstand, Jim Gallant’s Connecticut Bandstand, and David Hull’s Chicago Bandstand cost little to produce and provided their stations with opportunities to capitalize on the profitable teenage demographic.5 A sales pitch for The Milt Grant Show highlights the commercial appeal of these locally televised teen dance shows. Speaking directly to the camera, Grant addresses potential sponsors:

Gentleman, I’m about to offer you the best television buy in the world. I’m Milt Grant, the producer and emcee of The Milt Grant Show and record hop here in Washington … we have a winner that can win for you and your client … you see the ingredients are sure fire. First of all, we have the top records of our day. Then we have big named stars … and we have a studio audience of seventy sampling for your clients’ products. Some of our clients are Motorola, Pepsi-Cola, [and] the Music Box store … our commercials are thoroughly integrated with the program content. We have a winner and it’s growing. … Gentleman, here is the combination of sales, showmanship, audience, and price that makes the Milt Grant Show the best television buy in the world.6

While clearly hyperbolic, Grant’s pitch is indicative of how local deejays and television stations sold their dance shows to potential sponsors. To distinguish American Bandstand from these local programs, every aspect—from the show’s title, introduction, and set design, to Dick Clark’s banter before playing records—provided advertisers, record producers, and viewers with evidence of the program’s national reach. For fans of the locally produced Bandstand, the most obvious change when ABC started broadcasting the program nationally was the title, American Bandstand. (The show continued to use both names while it broadcast from Philadelphia, using American Bandstand for the national ninety minutes, and Bandstand for the opening and closing thirty-minute segments that were only broadcast locally). By calling the show American Bandstand, the program’s producers offered both an accurate acknowledgment of the affiliates broadcasting the program and an ambitious evaluation of the national audience they hoped would tune in. For viewers in other parts of the country, many of whom were already familiar with their own locally broadcast dance shows, the title immediately announced American Bandstand as the national offering.

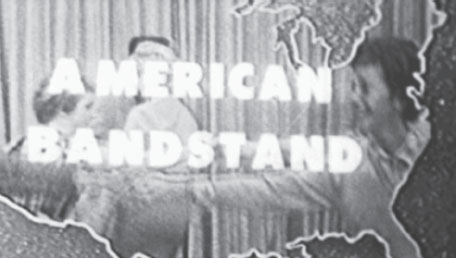

In addition to the name change, through its new introduction and set design American Bandstand encouraged viewers to imagine themselves as part of a national audience of television viewers. Each show opened with the camera focused on teenagers dancing in the studio to “Bandstand Boogie,” a big band swing style instrumental written especially for the show. The camera would pull back to reveal a large cut-out map of the continental United States made out of blue-glittered cardboard. With the teenagers now pictured as dancing inside this national map, the producers superimposed the show’s title at the center.7 Using this technique, within the first minute of each program American Bandstand depicted its studio audience as literally dancing across the nation.

American Bandstand’s studio design also integrated this national perspective. Across from Clark’s podium sat a second map of the United States featuring the call letters of each of the local television stations carrying the show. This map, which was visible periodically during each show as the camera tracked teens dancing around the studio, served as a reminder of the program’s national reach. More important, Clark frequently walked over to the board to make direct references to cities and stations in other parts of the country. “Let’s go over to the Bandstand big board to see which stations we are going to check today,” Clark announced in a typical episode in December 1957.8 With the camera focused in tight close-up on the map, Clark informed viewers that Frankie Avalon’s “De De Dinah” was topping the record charts in Buffalo, New York (home of affiliate WGR); Cleveland, Ohio (WEWS); Akron, Ohio (WAKR); and Youngstown, Ohio (WKST).9 In another show that same week, Clark highlighted stations in San Francisco (KGO); Stockton, California (KOVR); Fresno, California (KJEO); and Decatur, Illinois (WTDP) before introducing Sam Cooke’s “I Love You for Sentimental Reasons.”10 Built into the structure of each show, this affiliate map of the United States offered TV stations, advertisers, and viewers evidence that American Bandstand was a national program. With this national map of television stations, American Bandstand encouraged viewers to imagine a nation of audience members watching along with them.11 Within a broadcast medium that repeatedly sought to generate a sense of a national culture, American Bandstand stood out for its insistent and geographically specific reminders that viewers were part of a national television audience.

FIGURE 21. American Bandstand opening credits, with teens dancing behind a cut-out cardboard map of the United States and the show’s title superimposed at the center. Producers sought to remind viewers and advertisers about the national reach of American Bandstand in order to differentiate it from dozens of similar shows broadcast locally across the country. 1957–1958. Used with permission of dick clark productions inc.

FIGURE 22. Dick Clark talks with teens visiting American Bandstand from Los Angeles. American Bandstand’s studio featured a large map that included the call letters of each local affiliate that carried the show. American Bandstand Yearbook, 1958.

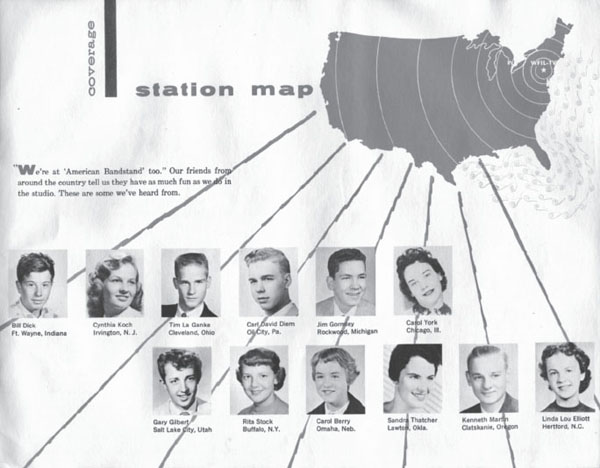

The American Bandstand Yearbook, 1958 reiterated this ideal of a national audience with a station map featuring thirty-four teenage viewers from twenty-one different states. The yearbook showed WFIL–TV’s signal reaching in concentric circles across the United States, and told advertisers and fans that these “friends from around the country” were “at ‘American Bandstand’ too.” This national map motif expanded on the WFIL–adelphia theme that WFIL originally used to sell the station’s four-state regional broadcast area. The photos of these teen viewers resembled headshots in a typical high school yearbook, but rather than representing a single city or town, the yearbook gathered teens from Fort Wayne, Buffalo, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans into a national cohort of teenage consumers. Despite this regional diversity, the fans highlighted in the yearbook reiterated American Bandstand’s white image of national youth culture.12

FIGURE 23. The American Bandstand Yearbook, 1958, picked up the station map theme to feature thirty-four teens from twenty-one different states. The fans highlighted in the yearbook also reiterated the white image of national youth culture constructed by American Bandstand. American Bandstand Yearbook, 1958.

Even when the station map was not pictured on the screen, Clark made frequent references to affiliated stations and markets when he presented records, introduced audience members from out of town, and opened viewer mail. In different programs, Clark told viewers about the popular records in Boston (WHDH) and Detroit (WXYZ), welcomed twin teenage girls from Minneapolis (WTCN) to the audience, and read a fan letter from Green Bay (WFRV).13 By integrating the station call letters in this way, Clark emphasized the national reach of American Bandstand while also providing affiliates with brief advertisements that raised their local profiles. In an era when local NBC and CBS affiliates as well as independent stations could elect to carry individual ABC programs, these affiliate advertisements were critical to the commercial success of American Bandstand and the network. Since Clark and ABC’s network executives worked on a market-by-market basis to increase the number of affiliates carrying the show, these station announcements also offered a warning to stations that considered dropping the show. On the December 17, 1957, show, for example, Clark read a letter from Aida, Oklahoma, that relayed news that the local affiliate (KTEN) threatened to replace American Bandstand with a locally produced dance program. Teenagers in Aida, the letter continued, protested by writing to the station to demand that KTEN keep American Bandstand on the air. The protests proved successful, and Clark thanked the teenagers for their efforts. Using less than a minute of broadcast time, Clark provided viewers across the country with a tutorial on how to compel affiliates to continue broadcasting the program. Moreover, these station announcements identified teenagers in different parts of the country as television consumers linked to both a specific market and the national market.

Out of these local markets American Bandstand’s map created a vision of a national market of teenage consumers that advertisers and record producers sought to reach. Although the teenage consumer market began developing in the decades before World War II, in the 1950s marketers and the popular press emphasized the discovery of a previously untapped market of teenage consumers.14 In 1956, for example, the Wall Street Journal described the nation’s 16 million teenagers as a “market that’s getting increasing attention from merchants and advertisers.” Estimating that teens spent between $7 and $9 billion annually, the article described how advertisers were turning to teenage-market researchers to help them win the brand loyalty of these customers at an early age.15 Foremost among these researchers, Eugene Gilbert generated many of the statistics that fueled the interest in the teenage market. Starting in the early 1940s, Gilbert, who called himself the “George Gallop of the teenagers,” hired a network of high school students to conduct market research among their peers. By the late 1950s, Gilbert wrote a syndicated newspaper column, “What Young People Think,” and published Advertising and Marketing to Young People (1957), encouraging marketers to develop specific strategies to reach teens.16 Gilbert’s Advertising and Marketing to Young People opens with charts emphasizing that the postwar baby boom had made eight- to eighteen-year-olds the fastest growing age demographic in the country. The size of the youth market, combined with young people’s willingness to try new products, made an “unbeatable selling formula” in Gilbert’s estimation. “Just look at youth!,” Gilbert advised readers:

No established pattern. … No inventory of treasured, and to many an adult’s way of thinking, irreplaceable objects. Youth … is the greatest growing force in the community. His physical needs alone constitute a continuing and growing requirement in food, cloths, entertainment, etc. It has definitely been established that because he is open-minded and desires to learn, he is often the first to accept new and forward-looking products.17

Gilbert’s statements of fact about the youth market were part of the midcentury growth of surveys about “average” Americans. In attempting to “reveal the nation to its members,” historian Sarah Igo contends, these “social scientists were covert nation-builders, conjuring up a collective that could be visualized only because it was radically simplified.”18 Gilbert’s writings on the youth market were influential because he provided pages of data on the consumer preferences of youth, thereby transforming millions of individual teens and pre-teens into a market niche. As evidence of a company eager to reach young consumers, Gilbert could have cited ABC’s attempt to outflank the larger networks by targeting teenage viewers with programs like American Bandstand. For his part, Clark echoed Gilbert’s descriptions of teens as a large, but underserved, consumer market. “It’s been a long, long time since a major network has aimed at the most entertainment-starved group in the country,” Clark told Newsweek in December 1957. “And why not? After all, teenagers have $9 billion a year to spend.”19 While Gilbert generated interest in teenagers as lucrative consumers, American Bandstand provided Clark with a platform to put Gilbert’s ideas into practice.

In this wave of attention focused on teenage consumer culture, American Bandstand stood out for the way that it showed teens using the sponsors’ products. When buying time on American Bandstand, sponsors like 7-Up, Dr. Pepper, Clearasil, and Rice-A-Roni also bought interaction between their products and the show’s teenagers. For example, after the opening shot of teens dancing behind the cut-out map of the United States in one 1957 episode, the camera focused on a 7-Up sign and bottles of the soda placed next to Clark at his podium. Clark read a letter from a viewer in Schenectady, New York, who sent him a bottle opener because he was unable to open a bottle of 7-Up in a previous show. After thanking the viewer for her letter and the gift and commenting on his thirst, Clark took an exaggerated swig of the soda. The camera cut to teenagers in the studio audience who asked for drinks of their own, which Clark promised to deliver after a short commercial. After a one-minute cartoon advertisement for 7-Up, the camera returned to a live shot of Clark handing out bottles of 7-Up from a cooler to an eager group of audience members. As Clark introduced “Get a Job” by the Silhouettes, the camera stayed focused on teens drinking 7-Up and milling about near the cooler through the first fifteen seconds of the song. Throughout the song, the cameras cut away from shots of teens dancing to return to the teenagers drinking 7-Up. All told, this 7-Up promo lasted nearly five minutes and was only the first of several in that episode.20

These interpolated commercials, which were common in radio and television shows in this era, provided American Bandstand’s viewers with daily visual evidence of teenagers’ eagerness to consume products.21 While such a message appealed to marketers looking to expand sales, images of teenagers as consumers also encouraged the home audience to join in by buying the sponsor’s products. The show’s advertisements focused on soft drinks and snacks—Popsicles, Mounds, Almond Joy, Dr. Pepper, and Welch’s grape juice all advertised on the show—all of which were aimed at teenage viewers and their parents in the after-school hours.22 American Bandstand’s afternoon broadcast time was also less expensive for sponsors. In 1958, these advertisers paid $3,400 per half hour compared to $30,000 to $45,000 for a half hour on a live music show in the evening.23 For this bargain rate American Bandstand offered sponsors an unusually deep level of interaction with teenagers in the studio audience and those viewing at home.

To recruit sponsors, ABC also drew on market research suggesting that many housewives watched the show. The network sent a press release proclaiming “Age No Barrier to Bandstand Beat” to local affiliates and sponsors, and during the broadcast Clark encouraged “You housewives [to] roll up the ironing board and join us when you can.”24 By appealing to both the advertising industry’s traditional view of housewives as archetypal consumers and the new interest in teenage consumers, Clark and ABC positioned American Bandstand to be as attractive as possible to advertisers.25 In turn, these advertisers ensured the show’s sustainability.

American Bandstand’s productions strategies also encouraged viewers to participate in the show by taking an interest in the show’s regulars and by learning dance steps. An October 1957 TV Guide review called attention to the show’s camera techniques: “[T]hanks to some camera work by director Ed Yates that would do credit to any TV spectacular there isn’t one of these amateur and largely anonymous supporting players who isn’t worth watching.”26 While teens danced in the studio, the show’s camera operators made frequent use of two types of shots. First, during slow dances they used extended close-ups on the couples’ faces that provided viewers with an intimate look at which teens were dancing together. In turn, the show’s regulars would jockey to dance in front of the cameras so they could be seen on television. Arlene Sullivan, who along with Kenny Rossi made up one of the show’s most popular couples, remembered that “it got to the point where the regular kids wanted to be on camera all the time, so Dick Clark would turn off the red light so we were supposed to not know which camera was on. But we always knew where the camera was. We were hams.” Asked how she knew which camera was on without the red light, Sullivan recalled, “Oh, you knew. You knew how they were focusing. And then Dick Clark would start to say, if he thought we were in front too long, ‘OK, Arlene and Kenny in the back, Franni in the back, Carole in the back.’ He wanted to give the other kids a shot.”27 Despite Clark’s prodding, the regular dancers were on camera enough to become celebrities to the show’s viewers and teen magazine readers. Teen magazine, for example, told readers they were “swamped with requests to do a story on the kids from Bandstand” and subsequently featured six cover stories on American Bandstand between 1958 and 1960, with profiles of current and former Bandstand regulars like Pat Molittieri, Kenny Rossi, and Arlene Sullivan. ‘Teen also published two eighty-page special issues for teens to read more about the show’s dancers.28 Daily television exposure and celebrity-style coverage in teen magazines made Bandstand’s regulars into what would later be called reality television stars. These nonprofessional performers became, as ‘Teen put it, the “most famous unknown[s] on TV today.”29 American Bandstand’s use of extended close-ups, coupled with numerous magazine profiles, invited viewers to follow along with the dating and style choices of the show’s regulars and provided viewers with information about another form of consumption.

When the cameras were not holding tight close-ups of the regulars’ faces, they were often focused on dancers’ feet. These close-ups on the dancers’ feet highlighted yet another product viewers could buy, Dick Clark American Bandstand Shoes. Teenagers could purchase shoes in the style popularized by the show’s dancers. In another sign of the Dick Clark’s quest to maximize profits, these shoes were advertised to black teenagers in the Philadelphia Tribune at the same time black teenagers were being turned away from the show’s studio audience.

These below-the-knee shots, ranging between fifteen seconds and a minute in duration, also captured the teenagers’ dance steps during fast songs such as “At the Hop” by Danny and the Juniors and “Great Balls of Fire” by Jerry Lee Lewis, and during group dance songs such as “The Stroll” by the Diamonds. Along with dance instruction diagrams in the show’s yearbooks and in teen magazines, these close-ups provided viewers with tutorials on the show’s dance steps and identified American Bandstand as the best source of information about “new” dances. The 1958 American Bandstand Yearbook emphasized this point on a page titled “a new dance every day”: “‘The Chalypso,’ ‘The Walk,’ ‘The Stroll’—the list of new dances you’ve seen first on ‘American Bandstand’ just seems to grow each day. How do they get started? Well, if you ask some of the guests at the program, ‘They just happen.’” 30 Despite the suggestion that “new dances have ‘just grown’ on the program,” most of these dances did not originate on American Bandstand. Rather, many of the dances originated at local teen dances or were performed by the black teenagers on The Mitch Thomas Show.

FIGURE 24. Thanks to daily exposure on American Bandstand, the show’s regular dancers became teen stars. Pat Molittieri and other regulars were featured in “My Bandstand Buddies” published by ‘Teen magazine. 1959.

FIGURE 25. This advertisement for “Dick Clark American Bandstand Shoes” ran in the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s leading black newspaper, at the same time black teenagers were excluded from American Bandstand. September 13, 1960. Used with permission of Philadelphia Tribune.

Ray Smith, who attended American Bandstand frequently and has done research for one of Clark’s histories of the show, remembers that he and other white teenagers watched The Mitch Thomas Show to learn new dance steps. Describing the “black Bandstand,” Smith recalled:

First of all, black kids had their own dance show, I think it was on channel 12, but one of the reasons I remember it is because I watched it. And I remember that there was a dance that [American Bandstand regulars] Joan Buck and Jimmy Peatross did called “The Strand” and it was a slow version of the jitterbug done to slow records. And it was fantastic. There were two black dancers on this show, the “black Bandstand,” or whatever you want to call it. The guy’s name was Otis and I don’t remember the girl’s name. And I always was like “wow.” And then I saw Jimmy Peatross and Joan Buck do it, who were probably the best dancers who were ever on Bandstand. I was talking about it to Jimmy Peatross one day, when I was putting together the book, and he said, “oh, I watched this black couple do it.” And that was the black couple that he watched.31

FIGURE 26. Close-up shot of dancers’ feet from American Bandstand episode (ca. 1957–58). These tight camera shots emphasized the program as the place to learn about new dances and encouraged viewers at home to follow along. Used with permission of dick clark productions inc.

These white teenagers were not alone in watching The Mitch Thomas Show. Smith’s experience of watching the show supports Mitch Thomas’s belief that “[American Bandstand teens] were looking to see what dance steps we were putting out. All you had to do was look at ‘Bandstand’ the next Monday, and you’d say, ‘Oh yeah, they were watching.’” 32 They were watching, for example, when dancers on The Mitch Thomas Show started dancing the Stroll, a group dance where boys and girls faced each other in two parallel lines, while couples took turns strutting down the aisle. Thomas remembers that the teens on his show “created a dance called The Stroll. I was standing there watching them dancing in a line, and after a while I asked them, ‘what are y’all doing out there?’ They said, ‘that’s The Stroll.’ And The Stroll became a big thing.”33

The Stroll was actually a new take on swing-era line dances, and while the teens on The Mitch Thomas Show did not invent the Stroll, they, along with young fans of black R&B in other cities, were among the first young people in the country to perform the new version of the dance.34 The Stroll was inspired by R&B artist Chuck Willis’s song “C.C. Rider,” itself a remake of the popular blues song “See See Rider Blues,” which was first recorded and copyrighted by Ma Rainey in the 1920s and was subsequently recorded by dozens of others artists. Following Willis, a string of other R&B songs were produced based on the dance. By late 1957, the Diamonds, a white vocal group that frequently recorded cover versions of black R&B songs, released “The Stroll,” a song made specifically for the dance. Dick Clark was a friend of the Diamonds’s manager, Nat Goodman, and told him: “if we could have another stroll-type record, you’d have yourself an automatic hit.”35 The Diamonds’ version outsold the others largely because American Bandstand played the song repeatedly. In addition to helping move the Diamonds’s version of the song up the charts, the frequent spins also falsely established American Bandstand as the originator of the dance. The show offered viewers instruction on how to do the Stroll by showing close-ups on the dancers’ feet during the dance.36 The show’s yearbook offered fans of more explicit instruction on the dance.

FIGURE 27. American Bandstand teens demonstrate their version of the Stroll. American Bandstand Yearbook, 1958.

All this emphasis on American Bandstand as the birthplace of the Stroll upset some of the teenagers on The Mitch Thomas Show. Thomas later recalled that Clark was gracious when he complained to him about American Bandstand taking credit for the dance. “I called Dick Clark and told him my kids were a little upset because they were hearing that the Stroll started on ‘Bandstand’” Thomas remembered. “He said no problem. He went on the show that day and said, ‘Hey man, I want you all to know The Stroll originated on the Mitch Thomas dance show.’” 37 While Clark was courteous in this instance in acknowledging the creative influence of The Mitch Thomas Show on American Bandstand, the television programs remained in a vastly inequitable relationship. The Mitch Thomas Show broadcast to the Delaware Valley on an independent station that was not affiliated with one of the three major networks. American Bandstand, on the other hand, reached a national audience of millions with the financial backing of advertisers, ABC, and Walter Annenberg’s media assets. The question of the Stroll’s origins remained contentious because such new dances were one of the many products that American Bandstand sold to viewers. The appropriation of these creative energies contributed to the frustration felt by black teens who were denied admission to the show. The dance styles perfected by the black teenagers on The Mitch Thomas Show did reach a national audience, but the teens themselves were not depicted as part of the national youth culture American Bandstand broadcast to viewers.

At the same time that American Bandstand’s producers excluded black teenagers from the program’s studio audience, the show’s image of youth culture moved ethnicity to the foreground. Whereas television programs with ethnic characters like The Goldbergs, Life of Riley, and Life with Luigi were being replaced with supposedly ethnically neutral programs like Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best, because of its specific local context, American Bandstand offered, in particular, working-class Italian-American teenagers from Philadelphia access to national visibility and recognition.38 Many of the show’s regulars viewed American Bandstand as a sort of televised audiotopia, a welcoming space that provided a unique exposure for Italian-American teens.

Arlene Sullivan recalled feeling like an outsider in her predominately Irish neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia. “I was very shy growing up,” Sullivan remembered. “A lot of kids were light eyed and red hair and blonde hair. I was really the only kid in the neighborhood who was kind of dark. I was half Italian and half Irish, but I really looked more Italian than I did Irish. And I always really felt like I was different from them.” In contrast, Sullivan felt that “being on Bandstand of course you meet up with everybody, and you tended to see the love that they have for you. And especially for me, I just embraced them all, because they liked me. I was just surprised, because I was such a loner. And having all of these people like me.”39 Sullivan became one of the show’s best-known dancers and appeared on the cover of Teen in 1959.

Frank Spagnuola, who grew up in an Italian section of South Philadelphia and danced on American Bandstand from 1955 to 1958, felt that the program introduced teens in other parts of the country to Italians: “When you say Italian, everybody in Philadelphia knew Italians, and in Reading [Pennsylvania], they knew about Italians, they didn’t have any there, but they knew about them. But in the South they never saw an Italian, so this was a big thing. Dark hair, little darker [skin], it was a big thing.”40 Sullivan’s dance partner, Ken Rossi, shared this view. In an interview conducted for one of Clark’s histories of the program, Rossi recalled that “[Arlene and I] both had that ethnic look, dark wavy hair and all that. … I think a lot of people in the viewing audience had never really been exposed to this kind of ethnic concept.”41

These recollections resonate with the 1961 findings of sociologist Francis Ianni, who suggested that “while there is not the same hostility and social distance that existed for the second generation teen-ager, Italo-Americans are still considered to be ‘different,’” and as a result, the Italian-American teenager “does not participate as an equal in teenage culture.”42 While Spagnuola and Rossi may overstate the lack of Italian-Americans in other states, the predominance of these teens would have been unique for most viewers of American Bandstand outside of the three major centers of Italian immigration (New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia). Television, in this case, transcended population patterns, bringing images of white ethnic teens into homes across the country.

In order to fully understand the significance of representing national youth culture through images of Italian-American teens, it is important to pay attention to what historian Thomas Guglielmo calls the distinctions between race and color before World War II, and between race and ethnicity in the postwar era. From the late nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century, Guglielmo argues that Italian immigrants and their offspring experienced prejudice based on their perceived difference from Anglo Saxon, Nordic, or Celtic “races,” but they were never systematically denied the institutional and material benefits of their “color” status as whites. As the definition of race shifted in the World War II era to refer to large groups such as “Caucasians,” “Negroes,” and “Orientals,” Americans of Italian descent became an ethnic group, and many Italian-Americans began to organize around a white identity.43 Guglielmo concludes: “In the end, Italians’ firm hold on whiteness never loosened over time. They were, at different points, criminalized mercilessly, ostracized in various neighborhoods, denied jobs on occasion, and alternately ridiculed and demonized by American popular culture. Yet, through it all, their whiteness remained intact.”44 While Guglielmo focuses on Chicago, available evidence from Philadelphia supports his argument. Italian-Americans did face incidents of housing and educational discrimination in Philadelphia, but these incidents were neither as sustained nor as systematic as the discrimination against the city’s black and Puerto Rican residents.45 While the visibility of Italian-American teens was unique within the late 1950s television landscape, it served primarily to alleviate ethnic rather than racial prejudice. Italian-American teenagers did not need American Bandstand to become “white,” but the show did help to cement their racial status.

The recognition American Bandstand offered to working-class Italian-American teenage girls and other girls across the country is also significant. American Bandstand recognized teenage girls for their interest in music and dancing and offered an after-school activity in an era when budget allocations limited the range of extracurricular activities available to young women in Philadelphia’s public schools. American Bandstand became an integral part of the peer culture in the Italian neighborhoods of South Philadelphia, where many teens watched the show religiously. Like other teens across the country, they talked about the program’s regulars, music, and fashions with friends during school, and they looked to the show to learn new steps that they could use at local dances, or to see which steps the show’s regulars had picked up from these same local dances. Unlike most other viewers, however, several of the show’s teenage regulars and musical guests came from their high schools or neighborhoods, offering a unique perspective on the show’s local and national popularity. In each of these respects, American Bandstand became part of the daily lives of teenagers. Anita Messina, for example, remembers American Bandstand being an important point of connection among her friends at Southern High School. Asked how often she watched the show, Messina recalled:

Every day. It was like bible. You’d run home from school, because then you became interested in the dancers, they became like your friends. “Oh so and so is dancing with this one, he was dancing with this other one for three days, I wonder if they broke up?” It was just like a way of life, if they were wearing something you had to go out and buy it. “Oh they had this kind of top, we’re going to buy that kind of top.” And Dick Clark, whatever records he put on, we had to go out in buy the records. It was big. It was really important to all of us to watch that show. … Usually everybody would go home after school to watch American Bandstand, and then they’d come out. I can’t remember too many of my friends not watching American Bandstand. It was a big part of our lives in my age group. It was a topic of conversation. If you saw something on Bandstand you’d go to school the next day and talk about it. “Did you hear what Dick Clark said? Did you see Frannie Giordano? Did you see that this one was dancing with that one?” If they did a new dance, “did you see the dance they did?” It was really big.46

The televisual boundaries of American Bandstand were also blurry for Messina and her friends. For example, when Messina entered and won the show’s contest to meet actor Sal Mineo, she remembers: “When my name came on it was like blood curdling screams. … And the next thing you know, because you live in the city, you heard screaming all down the block because everyone was watching it on TV. And there are like fifty kids banging on the door.” Messina’s friend and classmate Carmella Gullon also remembered American Bandstand as an integral part of the lives of teenage girls in her neighborhood. “Oh, god yeah, everybody [watched it],” Gullon remembered.

You’d come home from school and you’d watch it on television and you’d dance. If your girlfriends were there you would dance with your girlfriends, and if not you’d dance with your banister. … That’s what kids did. And I think girls more than guys. And the guys we knew were real good dancers, but I think more so girls, that’s just what they did.47

Messina’s and Gullon’s recollections speak to American Bandstand’s power to shape the consumption decisions and interests of teenage girls. More important, however, in the context of their peer groups, American Bandstand was important because it reflected their interest in music and dancing. These music-centered peer relationships resemble what musicologist Christopher Small calls “musicking” to describe the totality of a musical performance. “The act of musicking,” Small suggests, “establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies.”48 Television enabled American Bandstand to connect teenagers across the country, and at the same time, local teens in places like South Philadelphia felt intimately connected to this musical venue.

American Bandstand was especially important for Messina and Gullon because in the years they attended Southern High School (1958–61), the school offered only a limited number of after-school activities for girls. Darlina Burkhart, a friend of Messina’s who was in the same graduating class, remembered that while the Southern football team and other boys’ sports teams were a big deal, “there was nothing like that for girls.”49 Messina recalled, “My extracurricular activity was finding the closest dance to go to.”50 These dances, held at churches, school gymnasiums, social clubs, and recreational centers, were frequent gathering places for teens on both weeknights and weekends. Neighborhood churches in South Philadelphia, such as Bishop Neumann and St. Richard’s, hosted small dances, and St. Alice’s in suburban Upper Darby (just outside West Philadelphia) hosted some of the largest dances, with more than two thousand teens filling the church’s social center on Friday and Sunday nights.51

While the white teens at these dances shared an interest in rock and roll and R&B, class and ethnicity sometimes divided them. Gullon recalled one such incident:

We went to a dance in Upper Chichester in our senior year, and the suburbs were a lot different from South Philly. We went into the dance with high heels and teased hair and crinoline. And everybody there was flat hair, very collegiate … and we were in there and we were dancing and we just made up a dance and everybody started to follow us, and it was a lot of fun. We had a great time. But we were just so different looking when we went in there. We didn’t realize how different we would be until we went there. We stuck out like sore thumbs. Even when we went to St. Alice’s [in Upper Darby] … you didn’t really mingle with the [kids] from other schools.52

This clash in dress and hair styles between working-class and lower-middle-class teens from South Philadelphia and their wealthy and upper-middle-class suburban peers highlights the heterogeneity among different local peer groups in the Philadelphia area.

In its pursuit of a national audience, however, American Bandstand relied on the creative energy of Italian-American teens in constructing the show’s image of youth culture. While the styles American Bandstand allowed young people to wear were more conservative than those teens selected for neighborhood dances, by providing a daily television spotlight for music and dancing, American Bandstand validated the extracurricular activities valued by these working-class teenage girls from South Philadelphia. With American Bandstand, market formation and identity formation occurred simultaneously. The marketability of Italian-American teens and young women helped the show cultivate a national youth culture, while it also offered these teens a way to connect with their local peers and a way to imagine themselves as part of a national youth culture in which working-class Italian-American teens played a central role. American Bandstand, of course, was invested in selling products, not ethnic pride or gender equity, but the particular images through which the show sold youth culture elevated some teens while they also obscured others.

In its seven years as a network program broadcast from Philadelphia, American Bandstand encouraged viewers, advertisers, and television stations to view the show as the epicenter of American youth culture. From WFRV in Green Bay to KOVR in Stockton, California, the program offered daily reminders to viewers that teens across the country were watching American Bandstand, drinking the same sodas, eating the same snacks, and doing the same dances to the same music. In this way, American Bandstand played a crucial role in cultivating a market of teenage consumers. Building an image of national youth around simultaneous consumption proved very profitable for American Bandstand, as well as for the advertisers, record producers, and television stations that sought the attention of teenage consumers.

If the teenagers American Bandstand portrayed every afternoon provided the basis for an imagined national youth culture in the late 1950s and early 1960s, this imagined national youth culture, in turn, provided the template for the way the show would be remembered in subsequent decades as a televised audiotopia that defined a generation. In cultivating a national youth culture, American Bandstand also provided the raw material for generational memories. Black teens, however, were largely absent from this imagined national youth culture. As the next chapter demonstrates, American Bandstand’s producers maintained the show’s discriminatory admissions policies during its years in Philadelphia. As a result, the television program that did the most to define the image of youth in the late 1950s and early 1960s, an image that continued to represent the era in later decades, marginalized black teens. Black teenagers protested the program on several occasions, but these civil rights challenges are not part of the popular history of American Bandstand. The daily broadcasts that established American Bandstand as the heart of national youth culture also inaugurated an ongoing struggle over how and by whom the show’s relationship to segregation is portrayed.