Consulting the Alphabet Oracle

There are several ways you can cast the Alphabet Oracle depending on circumstances and your personal preferences. I suggest that you read them all, try a few, and decide which you like best. Really, you only need to learn one!

Alphabet Stones

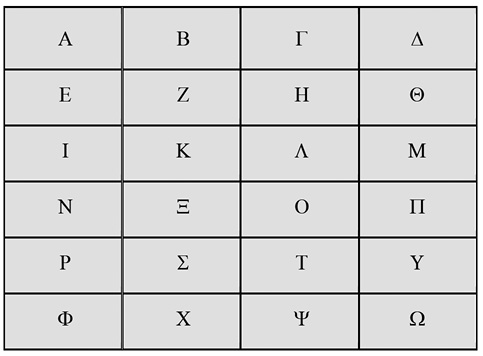

Since this is an alphabet oracle, the most basic method asks the gods to guide your hand in selecting a letter. One way is to mark twenty-four stones with the letters of the Greek alphabet, like those shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Greek alphabet stones. Left: Engraved crystal stones. Right: Engraved pot shards (ostracta). Both are modern.

These stones are like the rune stones used in rune casting. Table 1 shows the Greek letters in their archaic forms, which look rather like runes and are easier to carve or inscribe than the printed forms. Some of the letters look similar to each other (for example,  ), so mark them in some way so that you can tell them apart (e.g., by putting a line under the letter:

), so mark them in some way so that you can tell them apart (e.g., by putting a line under the letter:  ).

).

You can paint the letters on small round stones or carve them into pieces of wood. If you are used to working with polymer clays (for instance, Sculpey®), then you can impress the letters into small disks of clay. Often the ancient Greeks and Romans would use pot shards, that is, pieces of broken pottery; you can paint the letters on or scratch them with a large nail.

Although they are not as common as rune stones, you can buy a set of Greek alphabet stones, but it is much better to make your own. A set of stones is a magical tool, and it is most effective if it is psychically attuned to you, and making it yourself is one way to attune it. In other words, turn the making of the stones into a ritual. Keep in your mind your goals and intentions for the stones. Read the meaning of each letter (given in Chapter 7) and keep it in mind as you paint or carve that letter. Chant the name of each letter’s spirit over it. When your stones are complete, consecrate them as a ritual instrument (see Chapter 3 for a sample consecration ritual). Keep your stones in a special jug, box, or bag.

When you want to consult the oracle, invoke the gods (using, for example, a divination ritual from Chapter 3), and draw a stone without looking. You can either pick one quickly or rummage among them until one seems to “ask” to be chosen (it may feel warm or just gravitate to your hand). An ancient method of selecting a stone, which also works well, is to shake the stones in a bowl or frame drum until one jumps out. These are just examples, and you may find other ways to let the gods pick a stone for you.

Alphabet Leaves

Another way of consulting the oracle, which was also used in ancient times, is to inscribe the letter and oracle text of each oracle on a card (such as an index card), a flat piece of wood (such as a popsicle stick), or a metal leaf (Lat., lamella). These are analogous to rune staves. You can draw one in the same ways as drawing a stone and read the oracle text directly. Another technique is to scatter the leaves facedown, mix them around, and then draw one. This technique also works with stones if they are relatively flat. Your set of leaves should be made ritually and consecrated, like alphabet stones.

Such a practice might be the origin of a tradition about the Cumaean Sibyl, “whom the Delian seer/ Inspires with soul and wisdom to unfold/ The things to come.” She is supposed to have written her oracles on leaves, which were scattered about by the wind that reveals the divine presence, the physical manifestation of the god’s spirit.58 Perhaps this is how she cast her lots. In any case, Aeneas begs her:

Only to leaves commit not, priestess kind,

Thy verse, lest fragments of the mystic scroll

Fly, tossed abroad, the playthings of the wind.

Thyself in song the oracle unroll.

—Virgil, Aeneid VI.74–6, after Taylor translation

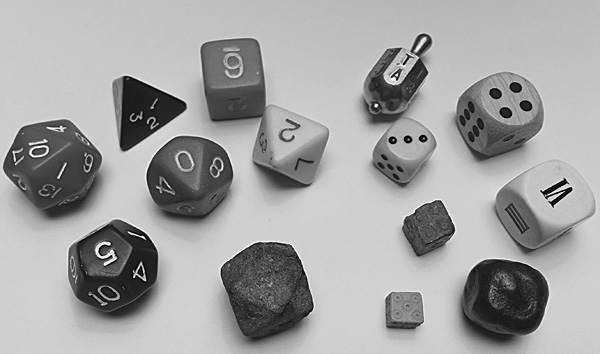

Two of the most common methods for consulting oracles in ancient times were to use astragaloi and dice, and many of the temples had them available beside a table or dice tray on which they could be cast. The table stood before an image of a god or goddess (often Apollo or Hermes), and so the divination was protected and guided by the deity, to whom the querent would pray for advice. Dice and astragaloi are still convenient today. It’s easier to carry a few of them than a whole bag of alphabet stones; in fact, one die or astragalos is enough! In a pinch you can borrow one or more dice for a divination, although they will not be consecrated for your use. I’ll talk first about astragaloi, since they are probably the more ancient procedure, and explain the use of dice and other methods as well.

What are astragaloi? True astragaloi (Lat., tali) are the pastern bones from the hind legs of goats, cows, and sheep, known in English as hucklebones or (less accurately) knucklebones. Our ancestors got them for free when they slaughtered livestock for food, and they probably accepted them as a gift from the animal spirit or from the god to whom the animal was sacred. Astragaloi were not only used for divination but were also used for games, like modern children use dice and jacks, and for gambling.59

The ancient historian Herodotus (fifth century BCE) tells a tale about how astragaloi and dice games were invented. There was a famine in the ancient land of Lydia and so the people decided to eat only on every other day. They invented all the games known to the Greeks, including dice and astragaloi, to distract them from their hunger on their fasting days. However, the famine continued for eighteen years, and so they decided that half the people would leave their country and start a colony across the sea. The ones to leave were chosen by lot, perhaps by casting dice or astragaloi. They founded a colony in northern Italy and named it Tyrrhenia after their leader Tyrrhenus. The Tyrrhenians are better known as Etruscans, and were considered masters of divination, who taught the divinatory arts to the Romans. Lydia was located in what is now western Turkey, and so it is interesting that many of the surviving alphabet and dice oracles come from western Turkey. (By the way, Herodotus’s story about the origins of the Etruscans is probably inaccurate.)

Historically, in Egypt astragaloi were used in board games as early as the First Dynasty (ca. 3500 BCE), but they do not seem to have been used for divination before the arrival of Ptolemy I (ca. 323 BCE). Astragalos games appeared in Turkey by 1300 BCE and are mentioned in the Iliad (eighth century BCE). Astragalos divination is practiced in the Far East, and could have originated in Tibet or India, but the first evidence for it appears after the arrival of Alexander and his army (ca. 324 BCE), so its origin is more likely in the West.

Back to the Alphabet Oracle. The ancient procedure for consulting the oracle was to roll five astragaloi (or, in a pinch, one astragalos five times). Unlike we do with dice, the ancients noted the numerical values of the downward faces. (The ancients might have read the downward faces of dice too.60 ) Of course, astragaloi don’t come marked with numbers, so you have to learn to tell the faces apart by their shape. If you look at a real astragalos and compare it to figure 2, you won’t have much trouble. Or, you can do like the ancients sometimes did, and mark the faces with pips or with Greek or Roman numerals.

Notice that, unlike a die, an astragalos can land on only four different faces. The first face shown in the figure has the value three; its Greek name, Huptios, and Latin name Supinum, both mean supine. It is one of the broad faces and has a fairly deep pit or depression in the middle. The next face (Grk., Pranês; Lat., Pronum, prone) has the value four; it is the rounder, somewhat cylinder-shaped broad face. The next (Grk., Khios, Chian; Lat., Planum, flat), which has the value one, is the narrow face with a sort of S-shaped depression. While the last (Grk., Kôios, Coan; Lat., Tortuosum, twisting), with value six, is the narrow face that has a somewhat flat, irregular surface.

Figure 2. Astragalos faces. Huptios/Supinum (3), Pranês/Pronum (4), Khios/Planum (1), Kôios/Tortuosum (6).

To consult the oracle, you add the numbers for the downward faces of the five astragaloi (or five casts of one astragalos). There are twenty-four possible totals: five to thirty, excepting six and twenty-nine, which are mathematically impossible (that is you can’t get them with combinations of five of 1, 3, 4, and 6). We do not have any direct evidence of how astragalos throws might correspond to the letters. Some scholars argue that the highest cast would be associated with Alpha and the lowest with Omega (so Alpha = thirty, Beta = twenty-eight, Gamma = twenty-seven, …, Psi = seven, Omega = five). However, all the other astragalos oracles from the ancient world arrange the throws in increasing order, and so we would expect Alpha = five, Beta = seven, …, Psi = twenty-eight, Omega = thirty. For example, if you rolled 3-1-4-1-1, the sum would be 10, which corresponds to Epsilon (E) if you use increasing sums, and Upsilon (Y) if you use decreasing. See Table 6, the Key for Consulting the Alphabet Oracle if you want to use either method.

You can “roll the bones” with your bare hands or with a dice cup or dice tower. A dice cup (Grk., phimos; Lat., fritillus) is a cylindrical container about four inches tall and a couple inches in diameter; sometimes it has ribs inside to help tumble the astragaloi. You shake the cup with your hand over its mouth and dump the astragaloi out. Alternatively, you can put the astragaloi into the top of a dice tower (Grk., purgos; Lat., turricula), in which baffles cause the lots to tumble before they spill out of the bottom. They are not new inventions; examples date from the fourth century CE (the Vettweiss-Froitzheim dice tower). You don’t need either of these devices; you can shake the astragaloi in your bare hand (or cupped hands) and throw them so they tumble. Some practitioners recommend blowing into your hand after you pick up the lots to “inspire” the divination.

Of course I have left an important question unanswered: “Where can I get astragaloi?” One answer is to make friends with ranchers who slaughter their own sheep, cows, or goats, and ask for the pastern bones from hind legs. Then you have to clean them up and prepare them. This solution is impractical for most people, so it is fortunate there are other options. One possibility is to use artificial astragaloi made from clay or carved from wood. If you look at some good pictures of astragaloi, you can make acceptable copies. You also can find artificial astragaloi for sale, so look on the Internet. You may be interested to know that artificial astragaloi are traditional and the ancients often used astragaloi made from carved stone, metal, clay, and other materials (Figure 3). The ancients sometimes marked the faces of their astragaloi with numbers, pips, or other signs, and you can too, especially if you have trouble telling the faces apart.

Figure 3. Astragaloi. Clockwise from upper left: two modern natural astragaloi; five modern artificial astragaloi; three ancient astragaloi (bone, stone, lead).

Long Dice

You can also make a kind of dice with four faces (sometimes called “long dice” or “stick dice”), which were also common in ancient Greece and Rome (Figure 4). You want to cut a piece of wood that is a few inches long and has a square or rectangular cross-section at most an inch on a side. The idea is that when you cast it, it can land on one of the four long faces, but not on the ends.

You can mark the numbers one, three, four, and six on the long faces. If your pieces have a rectangular cross-section, then mark three and four on the wider faces, and one and six on the narrower, just like the numbering of astragaloi. If it has a square cross section, you should still have three opposite four and one opposite six (opposites add to seven—Apollo’s number—on astragaloi as well as on dice). You can mark long dice with Arabic numbers 1, 3, 4, 6, but traditionally they would be marked with Greek numerals A (1),  (3),

(3),  (4), F (6). As will be explained in Chapter 6, Greek numerals used the obsolete letter F (digamma), which is not in the classical Greek alphabet. On some long dice B is substituted for F, and so we have the four letters

(4), F (6). As will be explained in Chapter 6, Greek numerals used the obsolete letter F (digamma), which is not in the classical Greek alphabet. On some long dice B is substituted for F, and so we have the four letters  , which are also the Greek numerals for 1, 2, 3, 4. Some long dice are marked with archaic Roman numerals: I, II, III, IIII, or with pips (dots). Long dice marked with dots and rings are known from the Indus Valley civilization 4,500 years ago. The oldest Indian examples are marked 1-2-3-4, but later ones are marked 1-3-4-6 (like astragaloi) or 1-2-5-6. Long dice are sometimes used for consulting the I Ching.

, which are also the Greek numerals for 1, 2, 3, 4. Some long dice are marked with archaic Roman numerals: I, II, III, IIII, or with pips (dots). Long dice marked with dots and rings are known from the Indus Valley civilization 4,500 years ago. The oldest Indian examples are marked 1-2-3-4, but later ones are marked 1-3-4-6 (like astragaloi) or 1-2-5-6. Long dice are sometimes used for consulting the I Ching.

You can cast long dice like ordinary dice and astragaloi or by rolling them out of your hand. When divination with astragaloi spread to the East, a new style was developed: a hole was drilled down through four dice (through the faces that would have been marked two and five) and they were strung on a stiff wire. The dice would be spun on the wire, and when it was put down, the uppermost faces would be noted. You can do this too.

Dice

Figure 5. Ancient and modern dice. Clockwise from upper left: modern gaming dice (4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, 12-, 20-sided); 8-sided brass teetotum; three modern dice; three ancient dice (stone, bone, lead); ancient 14-sided die.

Another way to consult the oracle is to roll five ordinary dice and to add up the uppermost numbers. Alternately, you can roll one die five times and add up its numbers. Either way, there are twenty-six possible values (five through thirty inclusive). Again, some scholars believe that the numbers corresponded to the letters in decreasing order (so Alpha = thirty, Beta = twenty-nine, Gamma = twenty-eight, …, Psi = six, Omega = five), but most ancient dice oracles are arranged in increasing order (Alpha = five, Beta = six, …, Psi = twenty-nine, Omega = thirty); take your choice. To consult the oracle, you add up the numbers and look in Table 6. Key for Consulting the Alphabet Oracle. to get the corresponding letter oracle. For example, if you throw 2-1-1-4-1, which add to 9, your oracle is Upsilon (Y) if you use the decreasing method, and Epsilon (E) for the increasing method. The correspondences are given in the Key for Consulting the Alphabet Oracle (Table 6).

There are only twenty-four letters in the Classical Greek alphabet, and so two of the sums do not have corresponding letter oracles. Some scholars think these sums corresponded to obsolete Greek letters that were eliminated in the classical alphabet (as explained in Chapter 6).61 Given the position of these letters (digamma and qoppa) in the pre-classical alphabet, they would correspond to the sums thirteen and twenty-five in the decreasing order, and to ten and twenty-two in the increasing order. Perhaps some ancient ancestor of the Alphabet Oracle provided oracles for these sums and their corresponding letters, but the surviving tablets do not. So what should you do if you cast one of these sums? One solution is to recast. However, such a cast may be considered a situation in which the oracle is reluctant to give an answer (see Chapter 3 for more information on dealing with miscasts).

Interestingly, both thirteen and twenty-five are uncanny numbers, associated with transgression of cycles or transcendence over them (e.g., twelve months, twenty-four hours). These numbers are often associated with sacrificed and resurrected gods (e.g., Dionysos was the Thirteenth Olympian, and it’s reasonable to associate these casts with him). The wholly negative interpretation of thirteen is no older than the Middle Ages, and twenty-five always has been accompanied by connotations of perfection (since it is the square of five).62

Dice seem to have evolved from astragaloi, for we have ancient astragaloi that have been sanded to make their faces flatter. (On the other hand, astragaloi are a lot like dice without their two and five faces.) Early dice have their pips in various arrangements, but by about 1370 BCE the common modern arrangement appears in Egypt; that is, opposite numbers add to seven and if you look at three consecutive numbers (1-2-3 or 4-5-6) they increase in a counter-clockwise direction. (This “right-handed” arrangement is standard in the West, but “left-handed” dice are common in the East.) Most ancient dice were marked with pips, like modern dice, but some were marked with Greek numerals ( ). The word “die” comes ultimately from Latin datum, “what is given,” which is a good way to understand an oracle. You cast dice with a dice cup, dice tower, or your bare hands (see under the section “Astragaloi”).

). The word “die” comes ultimately from Latin datum, “what is given,” which is a good way to understand an oracle. You cast dice with a dice cup, dice tower, or your bare hands (see under the section “Astragaloi”).

Teetotums

Closely related to astragaloi and dice are teetotums. They survive from the ancient world, and they were used for games such as “Put and Take,” but I don’t know of evidence that they were used for divination. The teetotum is a kind of top, which can land on one of a few sides; the most familiar modern descendant is the dreidel. It is essentially a long die that can be spun on its axis. The classical teetotum (like the dreidel) had four sides, typically marked “T” for totum (meaning “to take all”), “D” for deponere (“deposit one”), “N” for nihil (meaning “do nothing”), and “A” for auferre (meaning “to take one”). (In this order, corresponding to the numbers 4-3-2-1, opposites are on opposite sides of the teetotum; that is, “all” is opposite “none” and “put” is opposite “take.”) The word “teetotum” comes from “T totum,” the best cast. Teetotums (also called “put and takes”) can be made with any number of sides. You can order them online from game distributers or make your own.

Instead of an astragalos, you can use a traditional four-sided teetotum. Think of an ordinary die and imagine drilling a whole through its two and five faces. The remaining faces are one, three, four, six, just like an astragalos. Fix a short dowel through the hole for an axle. (Drilling a manufactured die is not such a good idea; you are better off starting with a wooden cube.) Similarly, you can use a six-sided teetotum instead of a die for divination; they are readily available. Ancient ones were marked 1-5-3-6-2-4 in clockwise order (opposites add to seven).

To use a teetotum, you spin it, usually by snapping its axle between your thumb and middle finger. For a good reading, it should spin for at least two seconds and land with one side clearly uppermost; otherwise, spin again. For the Alphabet Oracle, spin a four- or six-sided teetotum five times and interpret like astragaloi or dice, respectively. (For a teetotum with an odd number of sides, such as the three- and seven-sided teetotums for the Oracle of the Seven Sages, read the downward face.)

Twenty-Four–Sided Die

A very direct method of consulting the oracle is to cast a twenty-four–sided die. At least one such die, made of glass paste and marked with the Greek letters, survives from the ancient world and might have been used with the Alphabet Oracle. It can’t have been the most common method, or such dice would not be so rare compared to the thousands of surviving astragaloi and six-sided dice. Making a twenty-four–sided die is complicated, but they are used for gaming and can be bought for a few dollars. Try searching for “buy 24 sided dice” or “d24 dice.” These dice are labeled with the numbers one through twenty-four, so you will have to use Table 6 to determine the correct letter. Alternately you can buy an unmarked die and paint the letters onto its faces.

Alphabet Tablet

There is another way of letting the gods guide you to a letter. We don’t know if it was used in ancient Greece or Rome, but it has been traditional in Europe for a long time. Make up a card (Grk., pinax; Lat., tabula, tablet) with the Greek letters in squares as shown in Table 2. It is best to carefully make a nice tablet and consecrate it, but in a pinch you can draw it on any sheet of paper or even mark it in the sand.

To consult the oracle, close your eyes and place your finger on the tablet. Where you are pointing is your oracle. Or you can toss a small stone or coin on the tablet and see where it lands. If it bounces off the tablet or lands on a line, try again, but at most three times (see Chapter 3 on miscasts). A more modern device is a disk with the letters inscribed around the edge and a spinning arrow in the center.

Coin Methods

I don’t know if the ancients used this method, but it is similar to casting an ancient Chinese oracle called the Ling Ch’i Ching, which dates back to the Wei-Chin period (222–419 CE). This technique uses coins or other disks with distinct sides, which I’ll call the head and tail. There are several different ways to use this method, and I’ll begin with the simplest, which uses five coins of four different types. For clarity, I’ll assume we have two quarters and one dime, nickel, and penny. To cast the oracle, you shake up the coins, allow them to fall on a flat surface, and observe the heads and tails.

To explain reading the oracle, I will use “O” for a head (considered feminine) and “I” for a tail (considered masculine); they kind of look like their meaning. If the quarters show one head and one tail, the throw represents the number 1, for in Pythagorean numerology the monad is androgynous. If they are both heads, then write down 2, for even numbers are feminine and this throw is purely feminine. If they are both tails, write down 3, for odd numbers are masculine. Next observe whether the other three coins were heads or tails, and write O or I for each in order. For example, suppose both quarters were tails, the dime shows its head, and the nickel and penny are tails. We would write “3.OII,” where for clarity I have put a point between the quarters and the other coins. To determine the oracle, look up this cast in the Key for Consulting the Alphabet Oracle (Table 6), and you will see it is Upsilon (Y). Similarly, if the quarters were mixed (a head and a tail), and the dime, nickel, and penny were tail, head, head, respectively, we would write down “1.IOO,” which is Epsilon (E). (Of course, you don’t actually have to write down anything; you can look at the pattern of heads and tails and directly consult Table 6.)

As with dice and astragaloi, you don’t have to have five coins to use this method; you can do it by casting one coin five times. For the first two casts, you are concerned only with the number of heads and tails, not the order in which they occur. Mark 1, 2, or 3 as before. For the next three casts, record O (head) or I (tail) in order.

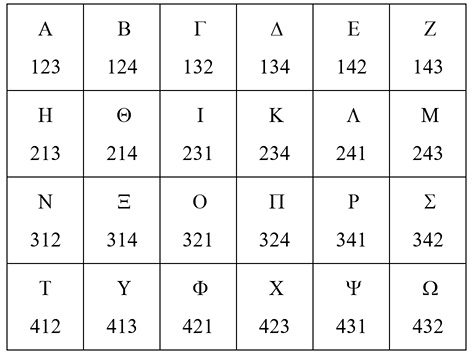

This coin method can be used easily to find the corresponding letter in the Alphabet Tablet with six rows and four columns shown in table 2. Notice that there are three pairs of rows, upper ( ), middle (

), middle ( ), and lower (

), and lower ( ). (These correspond to the units (1–9, omitting 6 = digamma), tens (10–90, omitting 90 = qoppa), and hundreds (100–900, omitting 900 = sampi) of the ancient Greek numeration system used in Greek gematria, described in Chapter 6.) Depending on whether the quarters represent 1, 2, or 3, you pick the upper, middle, or lower pair of rows. If the dime shows a head, you pick the upper row of four, or if tails, the lower. Within the row, if the nickel is a head, take the left pair of letters, otherwise the right pair. Finally, if the penny is a head, choose the left letter in the pair, otherwise the right letter. For example, suppose that the quarters were mixed, and the dime, nickel, and penny were tail, head, head, respectively. Since the quarters represent 1, we take the upper pair of rows (

). (These correspond to the units (1–9, omitting 6 = digamma), tens (10–90, omitting 90 = qoppa), and hundreds (100–900, omitting 900 = sampi) of the ancient Greek numeration system used in Greek gematria, described in Chapter 6.) Depending on whether the quarters represent 1, 2, or 3, you pick the upper, middle, or lower pair of rows. If the dime shows a head, you pick the upper row of four, or if tails, the lower. Within the row, if the nickel is a head, take the left pair of letters, otherwise the right pair. Finally, if the penny is a head, choose the left letter in the pair, otherwise the right letter. For example, suppose that the quarters were mixed, and the dime, nickel, and penny were tail, head, head, respectively. Since the quarters represent 1, we take the upper pair of rows ( ). The dime was a tail, so we take the lower row (

). The dime was a tail, so we take the lower row ( ); the nickel was a head, so take the left pair (EZ); the penny is a head, so take the left letter (E).

); the nickel was a head, so take the left pair (EZ); the penny is a head, so take the left letter (E).

If you have a set of alphabet stones, you can use them with the coin method as follows. Arrange your letter stones in six rows of four as in the Alphabet Tablet (Table 2). Cast two coins, or one coin twice (corresponding to the quarters), and based on the throw (OI or IO = 1, OO = 2, II = 3), eliminate the unneeded double rows. Cast again (corresponding to the dime) and eliminate the upper or lower row of four. Another cast (the nickel) tells you whether to eliminate the left or right pair of letters. The final cast (the penny) selects the oracle letter. You might wonder why you would want to use the slower coin method if you have a full set of alphabet stones, since you can simply draw one for the oracle. The reason is that the slower method better focuses the attention and helps to induce a meditative state, which may give a more accurate reading. (This is the reason that some I Ching readers, including me, prefer the complicated yarrow-stalk method to the easier coin method.) In divination, faster is not necessarily better.

Now a few words about the divinatory disks themselves. For clarity, I have explained the procedure in terms of ordinary coins, and they can be used effectively, but for spiritual purposes such as divination, ordinary coins may not be the best choice. You can, of course, use coins with some spiritual significance, such as ancient Greek or Roman coins bearing the image of a god (or inexpensive reproductions), I Ching coins, etc. You can also make a set of disks especially for divination. As we have seen, a complete set is five coins of four types with distinct heads and tails. For example, you can mark the head side and leave the tail side blank. Or you can mark both sides, either with abstract symbols (for example, O and I), or with something more concrete. For example, you can put a goddess on one side and a god on the other; you can use either an image of the deity or write their name. (Traditionally, O is female and I is male.) There are many other symbolic possibilities. Of course, as you have seen, you can do the procedure sequentially with just one disk.

You can make your disks out of a variety of material; wood was traditional in Taoist divination, because it is receptive. In Ancient Greek the words for matter, matrix (the heartwood, but also the womb), and mêtêr (mother) are all related; so wood symbolizes well the matter or substance of the divination. Nevertheless, clay, pottery, and metal are also good choices. Since there are four kinds of disks, they could be colored and made out of materials associated with the four elements. (You could mark the element’s symbol on the head side and leave the other blank.) Obviously, your disks should be flat enough that they can’t land on their edges!

Geomantic Method

Since all that is required to use the coin method is a sequence of fives heads or tails, many other traditional divination procedures can be adapted to this method. For example, as is done in geomancy, you can make five long rows of marks on a piece of paper or in the soil while keeping the query clearly in mind. The idea is to make each row long enough and quickly enough that you cannot immediately see how many marks you have made (a dozen is the minimum). Then you count off the marks in each row by twos to see if there is an even or odd number of marks. If it is even, you mark an O for that row, if odd, an I. Proceed to read the oracle the same way as the coin method.

A related technique comes from West African Ifa divination. String five two-sided objects on a thread (cowry shells are traditional). When you toss this device on the ground or a divining cloth, some of the objects will show their head side, others their tail side. Of course you need to know where to start reading, and the easiest way to do this is make one of the objects different from the rest (bigger, a different color, etc.); alternately, you can make the first two (corresponding to the quarters) distinct.

Bead Methods

A Tibetan procedure uses a long string of prayer beads (a mala); they were also used for prayer and meditation in the ancient Pagan West. Grab the string of beads with both hands in two random places, spaced well apart. Then count off by twos from each end (alternating your hands) until there are only one or two beads left between your hands. If there is one, mark I, and if two, mark O. Repeat this four more times to get a sequence of five Is and Os, and read them in the usual way. A slight variation requires you to count off only four times. The first time you count off by threes, alternating your hands, until there are one, two, or three beads between them. You interpret the number of beads like the number represented by the quarters. The remaining three times you count off by twos, as before, to get an I or O each for the dime, nickel, or penny. You may find these techniques convenient if you are accustomed to wearing a long string of prayer beads. (This method does not work so well with rosaries or other strings of beads that are divided into groups.)

Pebble Methods

A similar method uses a container, such as a bag or a jug, of any small objects, such as pebbles, marbles, beans, or unstrung beads. Take out a fairly large handful and count them back into the container by threes until one, two, or three are left, as in the coin method. Take another handful, and put them back two at a time until one or two are left. Repeat twice more to get the oracle. Alternately, count down to one or two pebbles five times, as in the geomantic method.

You can also use a container of beans, marbles, or other small objects of two kinds (colored or marked differently, etc.), and interpret one kind as heads and another as tails. Obviously, the objects of different kinds should be similar in feel so that you cannot tell them apart by touch. Draw five from the container one at a time and interpret them as heads and tails as in the coin method. Perhaps one of these methods is the “divination by pebbles” that the Thriai taught Hermes (as told in Chapter 2). We know that divination with beans was conducted at Delphi, and that a two-bean method was used there, but perhaps other bean methods were used as well. Large numbers of colored pebbles can be found in archaeological sites, sometimes with astragaloi.

Mixed Dice Methods

One simple method of consulting the Alphabet Oracle uses the Alphabet Tablet (Table 2,) with one ordinary die and two coins or other disks. Toss one coin and use it to pick either the left or right double column. Toss the second coin and use it to pick the left or right column out of the two. Finally, roll the die to pick one of the six rows. You can use a similar technique with the following tablet for the Three-Out-of-Four Method (see Table 3), which is more useful if you are interested in the correspondences to the letters that will be discussed in Chapter 6. Use the coins to pick the row and the die to pick the column.

You can also use special dice in a variant of the coin method. Instead of the quarters, you use a three-sided long die, which is a triangular prism. You can mark the faces 1, 2, 3 and read the face that is down. However, some of these long dice have the numbers near the edges, in which case you read the upmost edge. In addition, you need an eight-sided die or teetotum. A cast of these two dice is most easily interpreted by arranging the alphabet in six rows of four columns, as in the Alphabet Tablet (Table 2). Based on the cast of the three-sided long die, consult the first, second, or third double-row of four. This narrows it down to eight letters, and you pick one of these by casting the eight-sided die or spinning the eight-sided teetotum.

Three-Out-of-Four Method

I’ll give you one final, convenient method for consulting the oracle, although I don’t know of any evidence that it was used in ancient times. In this case, you need only four distinctly marked objects. They could be marked with four symbols (such as the four elements) or painted four colors. To cast the oracle, you draw the objects at random from a container, and their sequence determines the oracular letter. (Of course, once you see the first three, you know what the fourth will be, so the first three are sufficient to reveal the oracle.)

For convenience, I will use 1, 2, 3, 4 for the token’s markings, and in the Key for Consulting the Alphabet Oracle (Table 6) I show just the first three tokens drawn. So 123 = Alpha, 124 = Beta, 132 = Gamma, …, 432 = Omega. You will be able to understand the correspondence better if you write the alphabet in a square with four rows and six columns (see Table 3): (1) each row has the same first number, (2) within a row, each pair of columns have the same second number, and (3) within each pair, the third numbers are in increasing order.

How to Choose a Method

With all these different methods for consulting the Alphabet Oracle, you may be wondering which you should use. Should you learn them all? Probably not. The simplest and most authentic method is to use a full set of alphabet stones, so I suggest that you plan on purchasing or (preferably) making a set. However, it’s also useful to learn at least one of the other methods. You can use this until you get your alphabet stones, but it is also useful to know an alternative method in case you don’t have your alphabet stones with you, or if it’s inconvenient to carry them. For example, you can get by with a single coin, astragalos, or die. So I suggest that you read through all the alternative methods, maybe give them a try, and if one appeals to you, learn it. You can learn other methods later, but I don’t think it’s necessary (or even useful) to know them all. It is better to know a couple methods well, than all of them poorly.

58. Kerényi, Apollo, ch. 2.

59. Historical information about astragaloi and dice and their use in divination can be found in David, Games, Gods, and Gambling (New York: Hafner, 1962), chs. 1–2.

60. Peck, Harper’s Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities (New York: Harper & Bros., 1898), s.v. Talus.

61. Heinevetter, Würfel- und Buchstabenorakel, 35–39.

62. Schimmel, The Mystery of Numbers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 203–8, 237.