The Esoteric Greek Alphabet

In this chapter, you will learn some of the hidden secrets of the Greek alphabet. I will begin with its origin in history and myth and explain the magical correspondences of the letters. This allows you to use them as theurgic symbols, as explained in Chapter 2. The Greek letters also have numerical values, and this allows hidden correspondences among Greek words and names to be discovered (called isopsephy or Greek gematria). Finally, I will explain how to use the Greek alphabet for magic following a divination (analogous to rune magic). You don’t need to know any of this to use the Alphabet Oracle, so if lore and magic is not your thing, feel free to move on to Chapter 7, where you will learn to use the Oracle. You might be inclined to come back to this chapter later, after you experience for yourself the Oracle’s power.

Alphabet Lore

The Greek alphabet is one of the sacred alphabets of the West, and there is much esoteric lore associated with it. This information can be useful in more detailed divination and for alphabet magic (discussed in the next section). For example, suppose you cast ( ) “Thou hast gods as comrades and as aides.” That is good to know, but you might want to know who these gods are. To find out, you can do a second divination asking, “Which god is my comrade and aid?” Suppose you cast

) “Thou hast gods as comrades and as aides.” That is good to know, but you might want to know who these gods are. To find out, you can do a second divination asking, “Which god is my comrade and aid?” Suppose you cast  ; the god associated with this cast is Artemis, and so you should expect help from her.

; the god associated with this cast is Artemis, and so you should expect help from her.

There are many stories of the origin of the Greek alphabet. Historians tell us it is based on a Phoenician alphabet that was derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics and was brought to Greece around 800 BCE. Legends credit this to the Phoenician prince Cadmus, who founded the Greek city Thebes, but he is dated to around 2000 BCE, and so the story is a bit muddled (perhaps he brought the earlier Linear B writing system, which does go back to the second millennium BCE). The twenty-two–letter Phoenician alphabet contained only consonants, and one of the Greek innovations was to add vowels by repurposing unneeded consonants or inventing completely new letters. The result was the first true alphabet. However, it existed in many different versions in the Greek cities, in part to accommodate the different Greek dialects and pronunciations. In 403/402 BCE, Athens standardized the twenty-four–letter Greek alphabet presented in Chapter 4, which was adopted throughout Greece and is still used today.

Mythology credits the alphabet to several gods, including Prometheus (as mentioned in Chapter 2) and Hermes, who was said to have been inspired by observing cranes (his sacred bird) flying in letter-like formations; this is especially obvious in the fourth letter ( ), because the number four is sacred to Hermes. He brought the alphabet to Egypt, where he is known as Thoth and the ibis is his bird. Later, Cadmus brought a sixteen-letter alphabet from Egypt to Greece, and Euander (the son of Hermes and Carmenta, a goddess) took it from Greece to Italy, where it became the Etruscan alphabet. Subsequently, Carmenta adapted fifteen Etruscan letters for Latin, which was the ancestor of the Roman alphabet that we still use for English and many other languages.63

), because the number four is sacred to Hermes. He brought the alphabet to Egypt, where he is known as Thoth and the ibis is his bird. Later, Cadmus brought a sixteen-letter alphabet from Egypt to Greece, and Euander (the son of Hermes and Carmenta, a goddess) took it from Greece to Italy, where it became the Etruscan alphabet. Subsequently, Carmenta adapted fifteen Etruscan letters for Latin, which was the ancestor of the Roman alphabet that we still use for English and many other languages.63

Some say that the Moirai (Three Fates) themselves invented the first seven letters, and that certain men later increased the number to twenty-four. Hyginus (ca. 64 BCE–17 CE), in his Fables, says that Moirai invented five vowels and two consonants, but I think he is incorrect. He is not a very reliable source; his modern editor described him (in Latin) as “an ignorant youth, semi-learned, stupid.” 64 It is much more likely that they invented the seven vowels, which as pure sounds are akin to the heavenly spheres; they are spiritual, compared to the materiality of the consonants. In particular, the vowels correspond to the seven planetary spheres in the Ptolemaic/Chaldean order: A Moon, E Mercury, H Venus, I Sun, O Mars, U Jupiter,  Saturn.65 They also correspond to the seven pitches of the Phrygian mode (e.g., E, F, G, a, b, c, d), and thus to the music of the spheres. Vowel chants are common in the invocations of the Greek Magical Papyri.

Saturn.65 They also correspond to the seven pitches of the Phrygian mode (e.g., E, F, G, a, b, c, d), and thus to the music of the spheres. Vowel chants are common in the invocations of the Greek Magical Papyri.

There is esoteric significance to twenty-four, the number of letters in the classical Greek alphabet. For example, two letters are assigned to each of the Twelve Olympians and to each sign of the zodiac. (In the Alphabet Tablet, Table 2, the letters in the first column correspond to the fire signs, those in the second to earth, in the third to air, and in the fourth to water.) Marcus the Gnostic (second century CE) had a vision of a goddess called Alêtheia (Grk., Truth), who revealed a correspondence between these pairs of letters and twelve parts of her body. The ancient Greeks divided many things into twenty-four parts and labeled them with their letters. For example, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are each divided into twenty-four books, which are labeled with the letters of the alphabet. They divided the day into twenty-four hours, but differently than we do. The time between sunrise and sunset was divided into twelve equal hours, each ruled by one of the Twelve Hôrai (Grk., Hours), daughters of Helios (the Sun), and the night was similarly divided. Each Hôra oversees an activity, such as was common in Pythagorean communities.66 The Egyptians also had a twenty-four–character alphabet of sorts: hieroglyphs that represented single consonants, which they used to transcribe Greek and Roman names.67 (All these correspondences are given with the individual oracles, below.)

The Renaissance mage Henry Cornelius Agrippa (ca. 1486–1535) provides a different system of correspondences between the letters and the planets, signs of the zodiac, and five elements. (I don’t know if it goes back to ancient times.) He says the seven vowels are assigned to the planets, but he doesn’t specify the order. However, in the accompanying table they are assigned in the opposite order to that given above, that is, he uses the order of descent (A Saturn, E Jupiter, H Mars, I Sun, O Venus, U Mercury,  Moon). This disagrees with every ancient source we have (see, for example, Godwin, The Mystery of the Seven Vowels, chapter 3), and so I give the standard correspondences with Agrippa’s in parentheses with an asterisk. I have found the standard correspondences to work best, but you might prefer to use Agrippa’s. Next, he says the twelve single consonants are assigned to the zodiac signs in order (

Moon). This disagrees with every ancient source we have (see, for example, Godwin, The Mystery of the Seven Vowels, chapter 3), and so I give the standard correspondences with Agrippa’s in parentheses with an asterisk. I have found the standard correspondences to work best, but you might prefer to use Agrippa’s. Next, he says the twelve single consonants are assigned to the zodiac signs in order ( = Aries to Pisces). The remaining five consonants are double in that they combine two consonant sounds (

= Aries to Pisces). The remaining five consonants are double in that they combine two consonant sounds ( th,

th,  ks,

ks,  ph,

ph,  kh,

kh,  ps); they are assigned to the elements in the order of increasing subtlety (

ps); they are assigned to the elements in the order of increasing subtlety ( Earth,

Earth,  Water,

Water,  Air, X Fire,

Air, X Fire,  Spirit).68 These correspondences between the Greek letters and the terrestrial and celestial elements can be used for many purposes.

Spirit).68 These correspondences between the Greek letters and the terrestrial and celestial elements can be used for many purposes.

In one of Plutarch’s dialogues, we read that the twenty-four letters are divided into seven voiced (vowels), eight half-voiced (semivowels), and nine voiceless (consonants).69 The seven vowels  are associated with Apollo, for seven is his sacred number, and as the god of music, he increased the strings on Hermes’s lyre from four to seven (the diatonic scale).70 On the other hand, nine is the number of his Muses, who oversee the arts and sciences (which address everything on earth and in the heavens). The nine voiceless consonants are divided into three groups of three: smooth (

are associated with Apollo, for seven is his sacred number, and as the god of music, he increased the strings on Hermes’s lyre from four to seven (the diatonic scale).70 On the other hand, nine is the number of his Muses, who oversee the arts and sciences (which address everything on earth and in the heavens). The nine voiceless consonants are divided into three groups of three: smooth ( ), middle (

), middle ( ), and rough (

), and rough ( ).71 The Muses oversee nine cosmic spheres: the earth, the seven planetary spheres, and the sphere of fixed stars; Apollo rules over them all as the tenth. He is the source of their harmony and unity (and so his name was explained as a-pollon = not many, i.e., one). Finally, since the half-voiced letters (

).71 The Muses oversee nine cosmic spheres: the earth, the seven planetary spheres, and the sphere of fixed stars; Apollo rules over them all as the tenth. He is the source of their harmony and unity (and so his name was explained as a-pollon = not many, i.e., one). Finally, since the half-voiced letters ( ) partake of the power of both the voiced and the voiceless, their number, eight, is the mean of seven and nine; according to Pythagorean principles, a mean is required to bind the extremes together. Pythagoreans call the octad (number eight) “Embracer of all Harmonies” and “Cadmean” because Harmonia was the wife of Cadmus.72

) partake of the power of both the voiced and the voiceless, their number, eight, is the mean of seven and nine; according to Pythagorean principles, a mean is required to bind the extremes together. Pythagoreans call the octad (number eight) “Embracer of all Harmonies” and “Cadmean” because Harmonia was the wife of Cadmus.72

We also read in Plutarch that the Cadmean alphabet had sixteen letters, because it is four times four, and four is Hermes’s number.73 Later, Simonides and Palamedes each added four more letters, therefore bringing it to completion at twenty-four; that is, six fours. For, according to Pythagoreans, the triad is the first perfection, for it has beginning, middle, and end, and the hexad (number six) is the second perfection for it is the sum of its divisors (6 = 1 + 2 + 3, 6 = 1 × 2 × 3). Moreover, twenty-four is also the product of the first perfection (the triad) and the first cube (the octad, for eight is two cubed, 8 = 23 = 2 × 2 × 2). They also call the octad “Mother,” for it is the extension into three dimensions of the dyad (number two), which they call “Rhea,” the Mother of the Gods.

As you can see, there is hidden significance to the fact that the classical Greek alphabet has twenty-four letters, but for some esoteric purposes we use an older twenty-seven–letter Greek alphabet, which included three obsolete letters that were retained from pre-classical Greek alphabets although unneeded for writing classical Greek. The three obsolete letters are F (called digamma or wau, which looks like our F and is its ancestor),  (called qoppa, the ancestor of our Q), and

(called qoppa, the ancestor of our Q), and  (called sampi because it looks like pi,

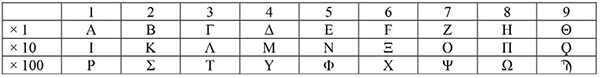

(called sampi because it looks like pi,  ). From at least the fifth century BCE, this twenty-seven–letter alphabet was used for numerals in ancient Greece; the letters alpha through theta stood for one to nine, the letters iôta through qoppa for ten to ninety, and the letters rho through sampi for one hundred to nine hundred (see Table 4). Since twenty-seven is the cube of three (that is, three to the third power: 27 = 33 = 3 × 3 × 3), it is an especially holy number (for some of the meaning of the cubes eight and twenty-seven, see my Pythagorean Tarot, pages 406–11 and 433–8).

). From at least the fifth century BCE, this twenty-seven–letter alphabet was used for numerals in ancient Greece; the letters alpha through theta stood for one to nine, the letters iôta through qoppa for ten to ninety, and the letters rho through sampi for one hundred to nine hundred (see Table 4). Since twenty-seven is the cube of three (that is, three to the third power: 27 = 33 = 3 × 3 × 3), it is an especially holy number (for some of the meaning of the cubes eight and twenty-seven, see my Pythagorean Tarot, pages 406–11 and 433–8).

Therefore, for example, the ancients might write  for 612 (the prime ' indicates a number). This correspondence implies, however, that every Greek word has a numerical value; for example,

for 612 (the prime ' indicates a number). This correspondence implies, however, that every Greek word has a numerical value; for example,  (Zeus) also has the value 612 (

(Zeus) also has the value 612 ( = 7 + 5 + 400 + 200 = 612). The study of the numerological significance of Greek words is called isopsephy from iso- (equal) and psêphos (pebble), since the ancients calculated with pebbles. Sometimes it’s called “Greek gematria,” but the art seems to have originated with the Greek alphabet and was only later applied to the Hebrew alphabet. Two words with the same numerical value (or differing by only one) are called isopsephic (Grk., isopsêphos) and are numerologically linked. One explanation for ignoring differences of one (called colel) is that The Inexpressible One is in everything. For example, 1138 =

= 7 + 5 + 400 + 200 = 612). The study of the numerological significance of Greek words is called isopsephy from iso- (equal) and psêphos (pebble), since the ancients calculated with pebbles. Sometimes it’s called “Greek gematria,” but the art seems to have originated with the Greek alphabet and was only later applied to the Hebrew alphabet. Two words with the same numerical value (or differing by only one) are called isopsephic (Grk., isopsêphos) and are numerologically linked. One explanation for ignoring differences of one (called colel) is that The Inexpressible One is in everything. For example, 1138 =  (Leto), the mother of Apollo, which is isopsephic with 1139 =

(Leto), the mother of Apollo, which is isopsephic with 1139 =  (delphus, “womb”), from which Delphi is named (recall Chapter 2). Further, “The god Apollo” (

(delphus, “womb”), from which Delphi is named (recall Chapter 2). Further, “The god Apollo” ( = 1415) is isopsephic with twice the value of “The god Hermes” (

= 1415) is isopsephic with twice the value of “The god Hermes” ( = 707), which links them together (Hermes is Apollo’s younger brother, see Chapter 2). Finally, TO APPHTON EN (The Inexpressible One) and

= 707), which links them together (Hermes is Apollo’s younger brother, see Chapter 2). Finally, TO APPHTON EN (The Inexpressible One) and  (agnôs, “unknown,” “obscure,” “unintelligible”) both equal 1054, for The Inexpressible One is beyond rational grasp. Isopsephy can reveal hidden connections between the meanings of Greek words.

(agnôs, “unknown,” “obscure,” “unintelligible”) both equal 1054, for The Inexpressible One is beyond rational grasp. Isopsephy can reveal hidden connections between the meanings of Greek words.

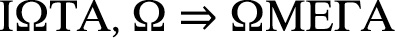

As explained in Chapter 2 (under “Theory of Divination”), Neoplatonists understand the Cosmos to be an emanation from The Inexpressible One, through the Cosmic Mind and Cosmic Soul into the Cosmic Body, which is the material world. Marcus the Gnostic illustrated this with an analogy. Take a Greek letter, such as Ι (iôta). In Greek its name is spelled  , which we can think of as its emanation and unfolding on a lower level,

, which we can think of as its emanation and unfolding on a lower level,

. But each of the letters of

. But each of the letters of  has its own emanation on a yet lower level:

has its own emanation on a yet lower level:

(ômega),

(ômega),  (tau),

(tau),  (alpha). Each letter in these names has further emanations in lower levels, and so on to generate the infinite multiplicity of the cosmos.

(alpha). Each letter in these names has further emanations in lower levels, and so on to generate the infinite multiplicity of the cosmos.

I’ve chosen iôta as an example for a particular reason, for this vowel corresponds to the Sun among the planets and is therefore in the most direct line of emanation from The One: One  Apollo

Apollo  Helios (Sun). Now consider the name

Helios (Sun). Now consider the name  . It includes the Gnostic divine name

. It includes the Gnostic divine name  , which among other things, symbolizes the Sun (I) as ruler over all the other planets, from the Moon (A), the nearest, most changeable planet, to Saturn (

, which among other things, symbolizes the Sun (I) as ruler over all the other planets, from the Moon (A), the nearest, most changeable planet, to Saturn ( ), the farthest and slowest moving planet. They are like bookends: the Moon’s period is 29 ½ days, and Saturn’s is 29 ½ years. In Greek, the god Saturn is called Kronos, who was the father of Zeus and the other Olympians with Rhea, Mother of the Gods. Plato interpreted his name to mean Pure Intuiting Mind (from koreô, “to purify,” and nous, “intuiting mind”). Plotinus interpreted it as the fullness (koros) of the intuiting mind, which includes all the Platonic Ideas (symbolized by the myth that Kronos ate all his children before Zeus brought them forth into the light). Therefore, Saturn is sometimes called the Occult Sun, because it is the hidden source of illumination, the illumination sought by sages. The Chaldean Oracles inform us that the Moon is associated with Hekatê, the goddess of theurgy, whose womb brings the Ideas into manifestation in the material world.

), the farthest and slowest moving planet. They are like bookends: the Moon’s period is 29 ½ days, and Saturn’s is 29 ½ years. In Greek, the god Saturn is called Kronos, who was the father of Zeus and the other Olympians with Rhea, Mother of the Gods. Plato interpreted his name to mean Pure Intuiting Mind (from koreô, “to purify,” and nous, “intuiting mind”). Plotinus interpreted it as the fullness (koros) of the intuiting mind, which includes all the Platonic Ideas (symbolized by the myth that Kronos ate all his children before Zeus brought them forth into the light). Therefore, Saturn is sometimes called the Occult Sun, because it is the hidden source of illumination, the illumination sought by sages. The Chaldean Oracles inform us that the Moon is associated with Hekatê, the goddess of theurgy, whose womb brings the Ideas into manifestation in the material world.

What of tau? It was the last letter of the Phoenician alphabet, in which it was written as an X cross and had the name tâw, which means a mark or sign. Therefore,  is a sacred sign.74 By isopsephy its value is 1111, which symbolizes the emanation of The One through four levels of reality increasing in multiplicity (1

is a sacred sign.74 By isopsephy its value is 1111, which symbolizes the emanation of The One through four levels of reality increasing in multiplicity (1  10

10  100

100  1000). It has the same value as

1000). It has the same value as  (haplôs), which means “singly, in one way, simply, absolutely” (characteristics of The One), and with

(haplôs), which means “singly, in one way, simply, absolutely” (characteristics of The One), and with  (ho martus, the witness). By colel it is isopsephic with

(ho martus, the witness). By colel it is isopsephic with  (ho sophos, the wise man),

(ho sophos, the wise man),  (mathêma hormaô, “I incite learning”), and

(mathêma hormaô, “I incite learning”), and  (ho mikros kosmos, the microcosm), all with the value 1110, and it is isopsephic with twice

(ho mikros kosmos, the microcosm), all with the value 1110, and it is isopsephic with twice  (phêmê, heavenly or prophetic voice). All of these words and phrases point to The One as the source of wisdom and oracular knowledge.

(phêmê, heavenly or prophetic voice). All of these words and phrases point to The One as the source of wisdom and oracular knowledge.

There is also an esoteric connection between the alphabet and the daily phases of the moon. There are approximately 29½ days from one new moon to the next (the synodic month), and many ancient cultures around the world associated twenty-nine or thirty animals or other symbols with each of these phases. Remarkably, the ABC order of our alphabet (or  of Greek) is preserved in many ancient scripts, the oldest of which is the Ugaritic script, used 1400–1200 BCE. This script had thirty letters and seems to have been based on an earlier twenty-seven–letter script extended to accommodate all the moon’s phases. In fact, some authors think that the letters were originally signs for the thirty lunar animals, and that only later were they used to represent sounds. The Phoenicians selected twenty-two of these letters to write their language, preserving the order found in the Ugaritic script. The twenty-seven–letter Greek alphabet restores some of the omissions and adds new letters at the end. The twenty-seven Greek letters correspond to the days when the moon is visible, from new moon (first visible crescent) to old moon (last visible crescent); the dark of the moon has no letters in Greek.75

of Greek) is preserved in many ancient scripts, the oldest of which is the Ugaritic script, used 1400–1200 BCE. This script had thirty letters and seems to have been based on an earlier twenty-seven–letter script extended to accommodate all the moon’s phases. In fact, some authors think that the letters were originally signs for the thirty lunar animals, and that only later were they used to represent sounds. The Phoenicians selected twenty-two of these letters to write their language, preserving the order found in the Ugaritic script. The twenty-seven–letter Greek alphabet restores some of the omissions and adds new letters at the end. The twenty-seven Greek letters correspond to the days when the moon is visible, from new moon (first visible crescent) to old moon (last visible crescent); the dark of the moon has no letters in Greek.75

We know that as early as the sixth century BCE the ancient Orphics associated animals with the days of the lunar month, but their correspondences have not survived. On the other hand, we have a list of twenty-seven correspondences from an invocation of the Moon (Mênê) in the London Magical Papyrus: ox, vulture, bull, cantharus-beetle, falcon, crab, dog, wolf, dragon, horse, she-goat, asp, goat, he-goat, baboon, cat, lion, leopard, field mouse, deer, multiform maiden (a description of the goddess Hekatê), torch, lightning, garland, caduceus (herald’s wand), child, and key. The last seven, associated with the last week of the waning moon’s visibility, are all symbols associated with Hekatê as a goddess of the underworld. These twenty-seven lunar symbols correspond to the letters of the Greek alphabet, and are given in the correspondences in the Alphabet Oracle text (Chapter 7).76

Alphabet Magic

If you are familiar with runes, you know that they can be used for magic as well as for divination, and the Greek Alphabet Oracle can be used in a similar way. The runes represent forces, and so it is natural to use them singly or in combination to achieve some purpose. In contrast, the Alphabet Oracles are answers to questions, and so the normal way to use them is to make a talisman to strengthen a positive response or to weaken a negative response. The oracles tell you what will happen if the current conditions continue, or they give you conditions under which an outcome will occur, but a talisman can help to change or reinforce these conditions.

For example, suppose you have asked about the success of a project and you cast  (Pi) “Passing many tests, you’ll win the crown.” The oracle predicts that your project will eventually succeed in spite of difficulties along the way, so your talisman could invoke the god’s aid in passing those trials. You might invoke Apollo or Heracles (who founded the Olympic games and was later deified) to empower a success talisman. On the other hand, suppose you cast M (Mu) “Make no haste; in vain you press ahead.” In this case you might make a talisman to help restrain yourself and to request insight as to when progress is possible (as discovered, perhaps, by another divination). You could invoke Athena to grant you prudence so you act wisely.

(Pi) “Passing many tests, you’ll win the crown.” The oracle predicts that your project will eventually succeed in spite of difficulties along the way, so your talisman could invoke the god’s aid in passing those trials. You might invoke Apollo or Heracles (who founded the Olympic games and was later deified) to empower a success talisman. On the other hand, suppose you cast M (Mu) “Make no haste; in vain you press ahead.” In this case you might make a talisman to help restrain yourself and to request insight as to when progress is possible (as discovered, perhaps, by another divination). You could invoke Athena to grant you prudence so you act wisely.

For each of the Alphabet Oracles, I suggest qualities to infuse into your talismans and suggest gods to invoke to empower them (see Table 5. Information for Alphabet Oracle Talismans., Information for Alphabet Oracle Talismans, page 84–87). Of course, as previously mentioned, the ancients had gods corresponding to each Greek letter, but the gods I’ve listed in Table 5 are especially appropriate to the specific oracles. These are just suggestions, however, so please use your own judgment in choosing the intent of your talisman and the god(s) to invoke.

Usually your talisman will be a flat object (a lamella), such as a disk of metal, wood, or even paper. You can also use self-hardening clay or a polymer clay (such as Sculpey ® ), which has to be baked. You can inscribe it (carefully!) with an awl or a craft knife, or write or paint your inscription on it.

Inscribe one side with the vox magica for the oracle in a “grapelike figure,” that is, in a downward triangle, eliminating the first letter in each line. Make sure you have enough space for all the lines! For example, for  (Pi), which has the vox magica

(Pi), which has the vox magica  , inscribe:

, inscribe:

This invokes and concentrates the power of the letter into the talisman. While you are inscribing it, focus on the purpose of your talisman. Keep positive: concentrate on the goal and avoid thinking about negative outcomes. You can use the other correspondences to the letter (given with the oracles) in the design of your talisman or in the consecration ritual. For example, each letter has a numerical value, a hieroglyph, and astrological associations. In fact, you can write the vox magica in hieroglyphs (given with the individual alphabet oracles). Arrange them artistically, ordered generally, but not exclusively, left to right or top to bottom. Don’t forget to surround the name with a cartouche ( for left-to-right writing, vertical for vertical writing).

for left-to-right writing, vertical for vertical writing).

When you have constructed your talisman, you can consecrate it as follows. Prepare yourself and your ritual space as I described for the consecration ritual in Chapter 3. That ritual invoked Apollo, but you might want to invoke a different deity more appropriate to the purpose of your talisman. The following is the consecration ritual adapted to talismans:

The Operation:

1. If you are not working in consecrated space, then cast a circle or create sacred space in your accustomed way.

3. Invocation: While pouring libations and making offerings, invoke the god selected to empower your talisman:

Hear me, (name of god)!

(burn incense while saying:)

I offer Thee this spice, (name of god),

(names and epithets of the god)

Or by whatever name is thy delight,

approach and come thou to this sacred rite.

If ever I’ve fulfilled the vows I’ve made,

then hear me now and grant to me thine aid.

Accomplish now this deed, and as I pray

give heed to me, and to these words I say.

4. Purification: Hold your talisman to be consecrated in the incense smoke and pray:77

I have called on thee, the greatest god,

and through thee on all other gods

to purify this charm of every taint.

Protect this charm today and for all time,

and give it strength supreme, divine.

Give power, truth, and fortune to this charm.

For this consecration I beseech you,

gods of the heavens,

gods under the earth,

gods residing in the middle,

masters of the living and the dead,

you who hear the needs of gods and mortals,

you who reveal what’s been concealed!

Immortal gods! Attend my prayers and grant

that I may fill with spirit this, my charm.

5. Potentiation: For additional strength, the remainder of the consecration up to the release can be repeated seven times with increasing force and power:

Empower this talisman with (the qualities and powers you desire).

While concentrating on your talisman’s intent, intone sonorously the vox magica for the letter as given in Chapter 3 (e.g., Pü-raw-bah-rüp for  ).

).

6. Continue the empowerment as follows:

I conjure Earth and Heaven!

I conjure Light and Darkness!

I call the god who hath created all,

Complete this sacred consecration now!

The Gates of Earth are opened!

The Gates of Sea are opened!

The Gates of Sky are opened!

The Gates of Sun and Moon

and all the Stars are opened!

My spirit has been heard by all the gods,

So give now spirit to this mystery

that I have made, O gods whom I have named,

O gracious gods on whom I’ve called.

Give breath to this, the mystery I’ve made!

Esto!

7. Release: Bring the ritual to a definite end by making final thanks offerings and libations while reciting a dismissal such as this:

Depart, O Master/Mistress, to thy realm,

to thine own palace, to thy throne.

Restore the order of the world.

Be gracious and protect me, Lord/Lady.

I thank thee for thy presence here.

Depart in peace and joy. Farewell!

8. If you do not need to use it right away, leave your talisman on the altar until the next day. To protect it from stray influences, you may want to wrap it in silk or put it in a special box.

9. Your talisman will keep its charge better if each morning when you get up and each night before you retire, you repeat the potentiation, step 5 above, stating your intent and intoning the vox magica seven times. Keep your talisman protected when it’s not in use.

You can string your talisman on a thong or chain and wear it around your neck, or you can carry it in a small cloth or leather bag. The ancients sometimes wrote the spell on a piece of papyrus, which they rolled up and put in a closed metal tube strung around their neck. In Ancient Greek a talisman is called a períapton, which means “something tied on.”

When you no longer need your talisman, you should “retire” it by burning it (if paper or wood) or by burying it (if metal, ceramic, etc.). Thank the gods for their aid and fulfill any vows that you have made.

|

Letter |

Vox Magica |

Oracle Verse |

Talisman Goals |

Relevant Gods |

|

A (Alpha) |

|

All these things, he says, you’ll do quite well! |

Guidance, good fortune |

Apollo |

|

B (Beta) |

|

Briefly wait; the time’s not right for thee. (Both Apollo, Fortune bring thee aid.) |

Patience, good timing (Divine aid) |

Hermes (Apollo, Tychê) |

|

|

|

Gaia gives thee ripe fruit from thy work. |

Good results, help in work |

Gaia |

|

|

|

Dodge the dreadful deeds, avoiding harm. (Drive ill-timed is weak before the rules.) |

Prudence, caution (Appropriateness) |

Athena (Hermes) |

|

E (Epsilon) |

|

Eager art thou for right wedding’s fruits. |

Guidance, children, love |

Zeus, Hera |

|

Letter |

Vox Magica |

Oracle Verse |

Talisman Goals |

Relevant Gods |

|

Z (Zeta) |

|

Zealously avoid the harmful storm! |

Protection |

Poseidon |

|

H (Eta) |

|

Helios, all-watcher, watches thee. |

Protection, truth |

Helios |

|

|

|

Thou hast gods as comrades and as aides. (Thou hast gods as helpers on this path.) |

Divine aid and protection |

Athena, Ares, or any others |

|

I (Iota) |

|

In all things, thou shalt excel—with sweat! |

Strength |

Hephaistos |

|

K (Kappa) |

|

Contests with the waves are hard; endure! |

Endurance |

Poseidon |

|

Letter |

Vox Magica |

Oracle Verse |

Talisman Goals |

Relevant Gods |

|

|

|

Leave off grief, and then await delight. (Lovely bodes the widespread word all things.) |

Relief, joy (Good omen)

|

Aphrodite (Apollo, Tychê)

|

|

M (Mu) |

|

Make no haste; in vain you press ahead. (Mandatory toil: the change is good.) |

Patience, prudence (Strength, energy) |

Athena (Hephaistos) |

|

N (Nu) |

|

Now springs forth the fitting time for all. (Nike’s gift enwreathes the oracle.) |

Opportunity, timing (Victory, prize) |

Hermes (Nike) |

|

|

|

Xanthic Dêô’s ripened fruit awaits. (You can pick no fruit from withered shoots.) |

Good results (Timing, prudence) |

Demeter (Demeter) |

|

Letter |

Vox Magica |

Oracle Verse |

Talisman Goals |

Relevant Gods |

|

O (Omicron) |

|

Out of sight are crops that are not sown. |

Effort, foresight |

Demeter |

|

|

|

Passing many tests, you’ll win the crown. |

Victory |

Apollo, Heracles |

|

P (Rho) |

|

Rest awhile; you’ll go more easily. |

Patience, ease |

Aphrodite |

|

|

|

“Stay thou, friend,” Apollo plainly says. |

Patience, steadfastness |

Apollo |

|

T (Tau) |

|

Take release from present circumstance. |

Deliverance |

Ares, Artemis |

|

Y (Upsilon) |

|

Useless toil: this wedding isn’t thine! (Undertaking fine is held by deed.) |

Prudence (Courage) |

Athena, Hera (Athena) |

|

Letter |

Vox Magica |

Oracle Verse |

Talisman Goals |

Relevant Gods |

|

|

|

Forthwith Plant! For Dêô fosters well. (Faultily you act, and blame the gods.) |

Divine guidance and support (Responsibility) |

Demeter (Athena) |

|

X (Khi) |

|

“Happily press on!” says Zeus himself. (Happy end fulfills this golden word.) |

Energy, confidence (Good luck, success) |

Zeus (Hermes) |

|

|

|

Proper is this judgment from the gods. |

Justice |

Zeus, Dikê |

|

|

|

Otiose the fruit that’s plucked unripe. |

Patience, timing |

Demeter |

Table 5. Information for Alphabet Oracle Talismans.

63. Hyginus, Hygini Fabulae, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 277.

64. H. J. Rose in Hyginus, Hygini Fabulae. See also page 277.

65. Godwin, The Mystery of the Seven Vowels (Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes, 1991), ch. 3.

66. Hyginus, Hygini Fabulae, fab. 183, gives the names of the Twelve Hôrai; Iamblichus (On the Pythagorean Way of Life, ch. 21, ¶¶95–100; pp. 120–123) described the Pythagorean day.

67. Since hieroglyphs do not generally represent vowels, some of the hieroglyphs for consonants not needed in Greek were repurposed to write Greek vowels, but this was not always done consistently. See Gardner, Egyptian Grammar (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1957), 18–20, and Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary (New York: Dover, 1978), xi–xv. To avoid complications, I have regularized the correspondences.

68. Agrippa, Three Books of Occult Philosophy (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1993), I.74, pp. 223–5. The following is a little complicated, and I advise you to ignore it unless you are a language geek! In the classical period  were aspirated (pronounced t+h, p+h, k+h), and so they are double consonants according to Agrippa. Classical grammarians, however, classified

were aspirated (pronounced t+h, p+h, k+h), and so they are double consonants according to Agrippa. Classical grammarians, however, classified  (pronounced ks),

(pronounced ks),  (pronounced ps), and Z (classically pronounced zd) as double consonants, the rest as simple (Goodwin, A Greek Grammar, Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1892, §18). Nevertheless, in support of Agrippa’s classification, there is evidence that at other times they were pronounced

(pronounced ps), and Z (classically pronounced zd) as double consonants, the rest as simple (Goodwin, A Greek Grammar, Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1892, §18). Nevertheless, in support of Agrippa’s classification, there is evidence that at other times they were pronounced  (khs),

(khs),  (phs), and Z (z). (Allen, Vox Graeca, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968, 53–7; Goodwin, A Greek Grammar, §28(3); Woodard, Greek Writing From Knossos to Homer, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, §6.5). Therefore, Z could be considered simple, and Agippa’s five double consonants (

(phs), and Z (z). (Allen, Vox Graeca, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968, 53–7; Goodwin, A Greek Grammar, §28(3); Woodard, Greek Writing From Knossos to Homer, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, §6.5). Therefore, Z could be considered simple, and Agippa’s five double consonants ( ) have aspiration “h” in common. The ancients called them dasu (rough, hairy, bushy, not bare or smooth), and this “roughness” seems appropriate for the elements that constitute material nature.

) have aspiration “h” in common. The ancients called them dasu (rough, hairy, bushy, not bare or smooth), and this “roughness” seems appropriate for the elements that constitute material nature.

69. Plutarch, Plutarch’s Complete Works (New York: The Wheeler Publ. Co, 1909), Symposiacs ix.3.

70. On the strings of the lyre in Greek esoteric music theory, see Opsopaus, “Greek Esoteric Music Theory” at http://omphalos.org/BA/GEM.

71. Stanford, The Sound of Greek (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1967), 51–55. They fall into three classes: labial ( ), palatal (

), palatal ( ), and lingual (

), and lingual ( ), thus forming a three-by-three matrix.

), thus forming a three-by-three matrix.

72. Iamblichus, The Theology of Arithmetic (Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes, 1988), 102.

73. Plutarch, Plutarch’s Complete Works, Symposiacs ix.3.

74. Franklin, Origins of the Tarot Deck: A Study of the Astronomical Substructure of Game and Divining Boards (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1988), 132, adds that IOTA represents the quarters of the year, starting with the summer solstice.

75. Gordon, “The Accidental Invention of the Phonemic Alphabet, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 29 (1970): 193–197; Kelley, “Calendar Animals and Deities,” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 16 (1960): 317–337; Moran and Kelley, The Alphabet and the Ancient Calendar Signs (Palo Alto, CA: Bell’s, 1969); Weinstock, “Lunar Mansions and Early Calendars,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 69 (1949): 48–69.

76. Weinstock, “Lunar Mansions and Early Calendars”; PGM VII.780–785. The obsolete letters  , which are not used in the Alphabet Oracle, have the correspondences: F crab,

, which are not used in the Alphabet Oracle, have the correspondences: F crab,  leopard,

leopard,  key.

key.