Chapter 1

ANTE UP

A walk along modern Sacramento’s riverfront takes one through the living, breathing museum of Old Sacramento State Historic Park. Albeit perched some ten to eighteen feet above its original 1849 elevation (it was raised in 1863 to prevent frequent flooding from a quick-to-rise Sacramento River), the district’s smattering of cobblestones, boardwalks and false façades conjures forth a bygone era that remains a defining element in the region’s identity.

Inextricably tied to the emergence of Sacramento and the city’s enduring affection for historical memory is the single most coveted mineral in human history: gold. Few would disagree that James Marshall’s 1848 discovery of gold on the American River proved the seminal event in the birth and growth of the city. In the find’s wake, California would never be the same again. The Gold Rush unleashed a migratory thrust the nation wouldn’t see matched until the Dust Bowl and Great Depression of the 1930s. In six months alone, between the winter of 1848 and the spring of 1849, nearly 233 ships, most drunk with Argonauts, sailed through the Golden Gate.1

Amid this scene of gold dust dreaming, those who sensed the glint of a different type claimed a hand in the city’s fast rise. From riverboat captain to restaurateur to barkeeper, gold was not so much an “x” on the map as it was a thing to be leveraged for profit, a process often referred to as “mining the miner.” Among this bevy of incoming merchants were those who would open one of the most enduring standards of nineteenth-century America and the primary focus of this book: the saloon.

A perversion of the French word salon, meaning lounge or drawing room, the saloon, according to historian Richard Erdoes, “was often the first substantial building in a new settlement, the last to crumble when it turned into a ghost town.”2 Sacramento was no exception, as indicated by one of the city’s first historians, Dr. John Frederick Morse:

Long ere San Francisco could boast of a store or hotel that was even decently related to the immense commerce which she concentrated, her public plaza was margined by these saloons, which, in capacity, in bright and glaring illuminations, in gaudy and expensive furniture, would eclipse almost any of the concert, ball, or literary halls in the Atlantic states. And what was true of San Francisco in this particular was true for Sacramento and every other town which achieved importance in the year of ’49.3

As soon as Sacramento’s Front Street embarcadero was established, a colorful mélange of saloons followed, including the Round Tent, the Humboldt, the Oregon, the El Dorado, the Indian Queen, Lee’s Exchange, the Sazerac, the Fashion, the Bank Exchange and the Marion House.

The saloon’s existence, both in Sacramento and throughout the West, came with a certain measure of influence. It has been said, tongue-in-cheek, that with the exception of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, all Western history was made within the saloon. If only because it “fueled” so much of the raw bravado and nastiness behind events like the legendary shootout at the O.K. Corral and Sacramento’s own lynching of sad Englishman Frederick Roe, the social and historical significance of the saloon is impossible to overstate. Akin to this was the institution’s flexible function; while primarily a place for drink and game, it could be much more. As Erdoes notes, in “being all things to all men,” the saloon was “an eatery, a hotel, a bath and comfort station, a livery stable, gambling den, dance hall, bordello, barbershop, courtroom, church, social club, political center, dueling ground, post office, sports arena, undertaker’s parlor, library, news exchange, theater, opera, city hall, employment agency, museum, trading post, grocery, ice cream parlor.”4

While seemingly exhaustive, Sacramento would affirm—even add—to such a list. In 1854, Sacramento’s Eureka Bath House on Second Street, between I and J, boasted a “splendid bar…furnish[ing] everything in the way of refreshments.”5 Jack’s Saloon (owned by Jack Combes), on J and Front Streets, boasted its own shooting gallery that, in 1852, allowed the patron to sip his favorite elixir while also improving his shot. California’s very first theater, the Eagle Theater—improvised as it was—was set as an annex to Sacramento’s Round Tent Saloon, which opened in the fall of 1849. Some of the city’s first town meetings, notably those to discuss the “merits and demerits of the city charter,” were held in the St. Louis Exchange, one of Sacramento’s original saloons.6 The reader should be mindful of the saloon as not just a purveyor of vice and refuge, but a real prism of history and viable conduit to affecting a spectrum of changes.

Dr. John Frederick Morse, recorder of Sacramento’s early history and critic of the city’s first wave of saloons. California State Library.

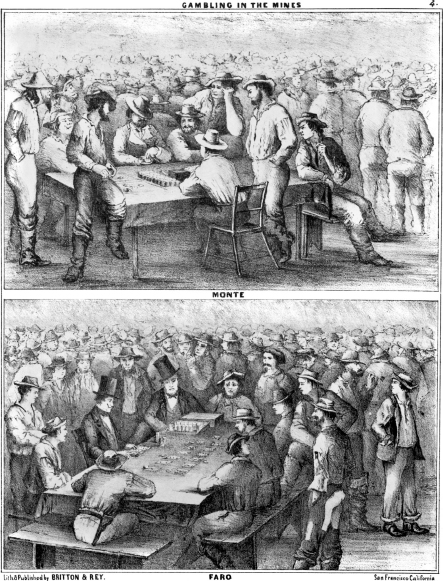

With both their versatility and influence understood, generally speaking, saloons went up for three primary reasons: gaming, drinking and socializing. For so many on the frontier, the lure of gambling was insatiable. Beyond entertainment and raw addiction, gaming meshed well with the frontier’s prevailing paradigm of adventurism and risk-taking. Morse described Sacramento’s perilous gambling culture as a “most Herculean grade so far as boldness and amounts hazarded were concerned. Every saloon, every table devoted to betting contingencies was literally crowded and sometimes so completely overwhelmed as to make it physically dangerous to be even a spectator of the scenes. Not one man in ten, if one in twenty, either by his absence or denunciation, condemned the universal mania for gambling which swept the country.”7

Most considered gambling to be a welcome diversion from the tumult of frontier life, and a talented and wily few, both reviled and revered, viewed it as an actual profession and a viable avenue toward fame and fortune. Gaming legends like the San Francisco–based Charles Cora, a master at faro, and William “Lucky Bill” Thornton, a notorious shell game operator, spent considerable time in Sacramento. What’s more, because big players meant big hands, the reported stakes for any number of games seem astonishing, even by today’s standards. For one Sacramento poker game, the ante was $100, while anywhere from $1,000 to $2,500 could be wagered on the best of hands.8 Speaking on his Gold Rush experience in Sacramento, miner and diarist Peter Decker claimed, “You enter and all is quiet games going on all around you without a word passing thousands of dollars laying [sic] on the tables. I have known men to lose $2,000 in an evening.”9

The history of the American West, distilled into popularity through film, literature and metaphor, would indicate that poker was the game; not so in antebellum Sacramento. At least in the early going, monte, faro and thimblerig ruled the day. Monte (or Tiger) was an import, finding its way to California from Spain via Mexico. By way of its Iberian origins, the game also was known as Spanish monte and played with a special forty-card deck with the following suits: clubs, swords, suns and cops. Like the more modern game of blackjack, or “21,” players went against the dealer. Accordingly, the dealer would turn up two cards and then a third from the deck. Players then bet on whether the third card, or “gate,” matched either one of the first two. As historian Mark Eifler states, “The game was regarded as one in which it was easy for a dealer to cheat a player, resembling a shell game.”10 For this reason, games played against a dealer and/or operated by the house were referred to as “banking games” and would eventually be outlawed.

Faro, or “Buck the Tiger,” also a banking game, was viewed as a prestige game and was popular—not simply because of the spectacle it offered the onlooker, but because it was known to give the player an almost even shot against the dealer.11 Its birth goes back to eighteenth-century France, while its name, derived from “pharaoh” or “pharo,” refers to the French reference to the King of Hearts as the pharaoh.12 Only card values, dealt from a fifty-two-card deck, were considered, thus making suits irrelevant. After the first card was exposed and discarded, twenty-five two-card pairs were laid out, leaving one unplayed card. The player would bet against the dealer, who drew two cards from the deck for each “turn.” Hands were decided when the player then placed a bet on the card he thought would win.

Thimblerig, known also as “the shell game,” was perhaps the most elementary of the early gambling diversions. With origins going back to ancient Egypt, it involved the bettor choosing which of three shells contained a pea. Despite the prospects of a one-in-three chance for victory, it was far from a sure thing, for as we will see, thimblerig acquired its dubious suffix for a reason.

Poker was born in the late 1700s in New Orleans and was perhaps named after a similar German game called Pochen or Poch. In its original, pre-1850 form, the game used a twenty-card deck. However, as the country pushed west, so too did the number of cards in play, as thirty-two were added for a total of fifty-two. Unlike monte, it demanded no permanent dealer, and quite unlike roulette, it required skill, both in reading the odds of one’s cards and the tenor of an opponent’s expression. The game, from beginning to end, was seductively easy: based on a random deal, the player with the highest hand—typically consisting of five cards—won the pot. Poker also was fast and could be played by as few as two or as many as ten. As Morse put it, poker “was a great game; although it was not so popular as a public betting medium, yet it was the test scene of the mightiest hazards then made.”13 Sustaining poker was not just its simplicity, but its status as a non-banking game. Near the end of the 1850s, when monte, faro and other house-controlled games were falling to the law, poker found its legs, eventually taking its place as Young America’s tacit—if not official—game of chance for decades to come.

The gamble was ever present in Gold Rush California, whether in wet or dry diggings or at the monte or faro tables. Center for Sacramento History.

By mid-century, alcohol consumption was also reaching new heights of popularity in all of American society. As historian Elliot West states, one could expect to see, in the nineteenth century, “as much as ten gallons of pure alcohol per year for every adult American, according to one estimate.”14 In the West, the level of drink’s appeal meant that one saloon could be found for every 50 to 100 persons.15 Placing Sacramento into a similar context, in 1851, it contained 7,000 residents, or 77 citizens for every establishment licensed to sell alcohol.16 While it is true that early Sacramentans, from miner to merchant, enjoyed drink, some of the more high-profile figures in town were more than equal to the task, as evidenced in the December 17, 1850 Sacramento Transcript, which states, “A New Species of Drunkenness—The Sacramento Transcript, in speaking of a soiree given by the Mayor (Horace Smith), says: ‘The Mayor of the city, the ladies, &c., were appropriately and elegantly drunk.’”17

There were a puritanical few, however, who sought a dry California. The goal was simple: halt the excessive consumption of alcohol and prevent a litany of consequential social problems such as poverty, crime, domestic tumult, hooliganism and immorality. Despite its youth, by late 1850, Sacramento possessed various temperance groups, with the Sons of Temperance, Pacific Star Chapter, being the oldest. With its original office located at 409 J Street, the sons maintained a close eye on the city’s saloon district, most of which covered the corridor from Front Street through Seventh Street.

The city also boasted no fewer than seven temperance-friendly churches. One, the so-called Baptist Chapel, encouraged citizens in the June 6, 1850 Sacramento Transcript to help assemble a “temperance organization.” The announcement continues to mention, and not absent a tone of moral entitlement, that “several speeches were expected and by representations made to us by those who know, persons who go will be treated, not with liquor, but with eloquence and intellect.”18

In 1839, John Sutter founded Sutter’s Fort. It was there that he established brewing and distilling facilities. Sacramento Public Library.

In the first few years of the 1850s, the sons and, later, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union pressed for restrictions on Sacramento saloons, marching in full regalia on July 4, 1851, to promote their righteous cause. Even the region’s first record of news, the Placer Times, displayed some modicum of temperance tendency, impishly reprinting in 1848 a New York Tribune mention of Captain John Sutter’s loss in the California gubernatorial election coming as a result of his being a “drinking man.” It goes on to note, “If this be so, it speaks well for California and places her considerably in advance of some of the older states.”19 As we will see, such moral suasion did little to affect a mostly male Sacramento population, whose demands for the saloon as both drinking place and social hub could not be denied.

Also worthy of mention is Sacramento’s placement in one of the world’s most lush agricultural regions, where all the raw material for drink was provided. Early on, the eye-popping size of even the most pedestrian crops made it into local newsprint. “Another Mammoth Melon,” “Enormous,” “Large Beet,” “Monster Melon” and “Huge Potatoes” were just a few of the more amusing headlines, but none could top that from September 5, 1854, in the Democratic Journal, which read “Siamese Watermelon.”20 The watermelon of note, grown in the garden of John Denn, was on display at the city’s Union Saloon, located at J and Third Streets. Coined a “most wonderful curiosity,” the melon was reported to weigh only twenty pounds, but having “united and formed one” from two melons, it conjured forth ample curiosity.21 The value of such agricultural riches was far from lost on locals, whose emerging confidence was evident in this passage from the Sacramento Daily Union in 1858, speaking to America’s mid-century standard in the distilled spirit: “We need not send to England for English Ale, or to Scotland or Ireland for Scotch or Irish whiskey…it will distill at our very doors, in the quality of any national liquor we may call for.”22 With wheat, barley, hops and various other flora in rich abundance and within easy reach to a vanguard of brewers, vintners and distillers, the city’s saloons would come to expect both high reliability and quality out of local alcohol production. This was especially true for the local production of flavorful English ales of the day that were highly susceptible to spoilage, thus making transport from the east out of the question. Sacramento would also see the emergence of the more effervescent and durable Teutonic-style lagers, thanks primarily to the spoil-resistant yeasts that were imported to North America by German immigrants in the 1840s.

The early American West’s unique frontier zeitgeist stood as an additional factor in the saloon’s rise. The West was not for everyone; life was hard and wickedly unforgiving. As was aptly stated in the August 11, 1849 Placer Times, those coming to California for the mining experience “should bear in mind that in California there is yet no law, but the will of the strongest and that life and property are insecure and that in the most favorable of circumstances, they must labor harder and fare [sic] worse than our Southern slaves, or state prison convicts. Then again, the climate is unhealthy. We dislike to be the prophet of evil, but we cannot forebear expressing the opinion that of those who go out to California, but few will return and that those few will not be much richer than before.”23

While not always the safest of spots, the saloon filled a void of insecurity and loneliness for untold numbers of people whose lives were susceptible to a unique type of angst. The effect of missed wives and families, the boredom of life in a virtual cultural/entertainment vacuum and the exhaustion that came with tearing through dry diggings one day and standing for hours in the most frigid of mountain streams the next all added up. This collective momentum of deprivation fomented a hearty thirst and, with that, demands for a place to quench that thirst.

It also bears mention that saloonists enjoyed access to a male-dominated market with a community of parched miners, impulsive adolescents and dusty frontiersman, all of whom were members of the gender that drank the vast majority of alcohol being consumed in nineteenth-century America.24 Accordingly, the 1850 census reveals the starkness of this gender disparity as it notes that 72 percent of the state’s population was between the ages of twenty and forty and that 92 percent of California’s total population was male.25

It’s within this colorful context that we consider various questions regarding saloon culture in early Sacramento. What were the city’s first and most notable saloons? Who established them? Who used them? From which vineyards, breweries and distilleries did they obtain their alcohol? And finally, what were the biggest threats to their existence, both manmade and natural? In addressing as much, we’ll attempt to construct a cohesive historical narrative, the extent of which will stretch from the area’s earliest European origins through the Gold Rush and near the early rumblings of the American Civil War.