Chapter 2

HAVE FORT OR TENT, WILL DEBAUCH: 1846–49

To determine Sacramento’s first saloon, it’s best to consider geography. Based on what a dearth of primary sources tells us, the city of Sacramento possesses one clear winner. If we consider the greater area where the American River meets the Sacramento River, we look no further than venerable Sutter’s Fort, located today on a grassy knoll between Twenty-sixth and Twenty-eighth Streets and K and L Streets.

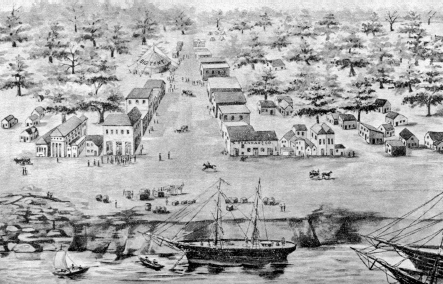

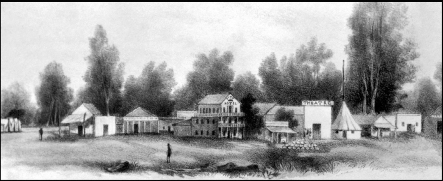

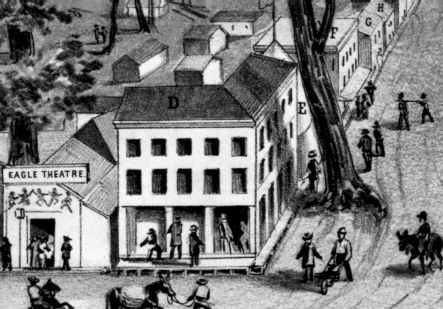

By most accounts, the first saloon in the city of Sacramento was as makeshift as they come: a few posts, some rope and a wind sail, offering “poor whiskey and poorer entertainment.”26 The Stinking Tent, as it grew to be known, was described by Morse as “the first place of gaming in this city…situated in ‘J’ Street between Second and Third, the present site of the Diana.”27 It was operated by James Lee, known through some sources as “Jimmie” Lee. Monte was the predominant game, and its distinction as the first gambling saloon in the city gives it obvious significance.28 An anonymously authored lithograph portraying Sacramento in July 1849 reveals an establishment located roughly between Second and Third Streets, and on J, called the “Big Tent.”29 Adorned with flags and gaudy capital letters spelling out its name, it is likely that this was nothing more than sanitization of the more amusing Stinking Tent.

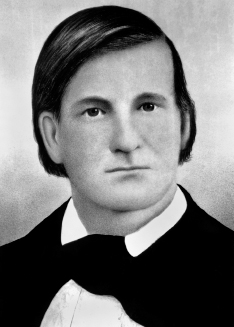

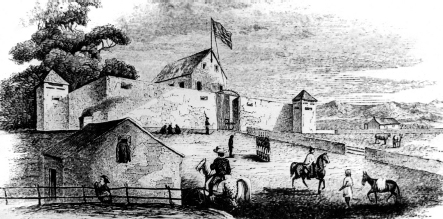

If we consider Sacramento proper to be our delimiter—looking east from Front Street to Twentieth Street—the Stinking Tent is it. However, reports that predate Morse point to Sutter’s Fort as the region’s first place of gaming and drink. William Robinson Grimshaw arrived in Sacramento in October 1848 to clerk for commercial dynamo Sam Brannan. Grimshaw’s reminiscences, written between 1848 and 1850, provide us with a taste of life at Fort Sutter, including its sundry entertainments. Insofar as gaming and drink in what appears to be late 1848, he states, “In the centre of the inside of the fort was a two story abode building, still standing, lower portion of which was used as a barroom with a monte table or two in it. This bar was crowded with customers night and day and never closed from one month’s end to the other.”30 Thompson and West’s definitive 1880 history of Sacramento County paints a somewhat similar picture of the Fort’s central building: “The front room [on the first floor] was used for drinking and gambling purposes…the bar was kept open night and day.”31 Gold dust proved to be the preferred payment in the bar as the miner “opened his purse and the barkeeper took a pinch of gold dust, the extent of the pinch being regulated by the quality and quantity of the liquor consumed.”32

An 1848 rendering of Sacramento’s J Street with the Big Tent in the upper section of the image. California State Library.

This barroom was likely under the operation of one Peter Slater, a native of Independence, Missouri; a Mormon; a widower; and a father of nine children. According to historian Laura T. Collins, Slater “made a fortune in the vending of drinks in this room—considering the price of fifty cents for a tablespoonful, $35.00 for a quart of brandy or whiskey.”33 Although not much is known of Slater, one of our most revealing descriptions of the man comes from Swiss immigrant and fort clerk Heinrich Lienhard. He recounts Slater’s running a bowling alley and selling food and assorted drinks at the Fort. He goes on to say, “Slater, who was not at all like his countrymen, seemed to have a fine character; he was a handsome, thoughtful, modest man who never harbored any ill will or tried to harm anyone. Many times I went to his store when I did not care to bowl or drink; he was always friendly and we often chatted together.”34 Lienhard “was favorably impressed by [Slater]; he seemed like a level-headed, sober and sensible man, the type who would not sacrifice principles for more gold.”

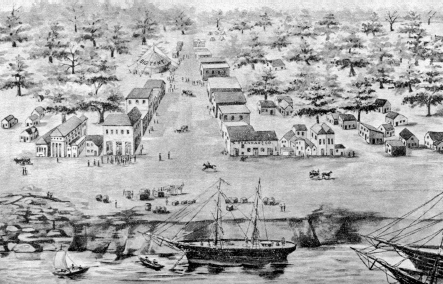

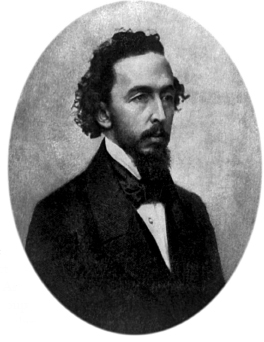

William Robinson Grimshaw, a clerk at Sutter’s Fort, provides one of the earliest descriptions of the structure’s saloon. California State Library.

This circa 1880 photograph shows Fort Sutter’s central building, home to Parly Slater’s saloon. Sacramento Public Library.

It is likely that this is the same Slater who, in the spring the 1849, ran and was elected to the city’s board of commissioners and the same man who, according to Sacramento Superior Court records, went on to run a ferry over the American River prior to dying of an indeterminable illness in December 1849. We also know that, at the time of his death, Slater’s personal property, appropriately enough, consisted partly of “242 three-quarter ounces of gold dust,” not to mention three dozen bottles of India Pale Ale.35

Underlining the presence of a fort saloon was Sutter’s immense fondness for drink. One Swiss visitor, Theophile de Rutte, recounted that during Sutter’s run for the governorship of California, he and others enjoyed a “bender” with the captain, lasting for “10 days and nights” and accounting for $11,500 in “champagne, fine wines and strong liquor.”36 De Rutte also mentions Sutter’s decision to situate his campaign headquarters in the basement of the Hotel de France (Sutter was an avid Francophile), where, of course, there was an open bar.

Lienhard was acquainted with Sutter through his work at the Fort. The former’s somewhat amusing testimony regarding Sutter’s penchant for alcohol follows:

I had no idea [Sutter] drank as much as he did. Soon I had an opportunity to become better acquainted with his habits and it was during my second week at the fort, I believe, that I saw him walking with an unsteady, swaying motion which left no doubt as to his condition…I learned from acquaintances, who had known Sutter for longer time and more intimately, that he was often intoxicated.37

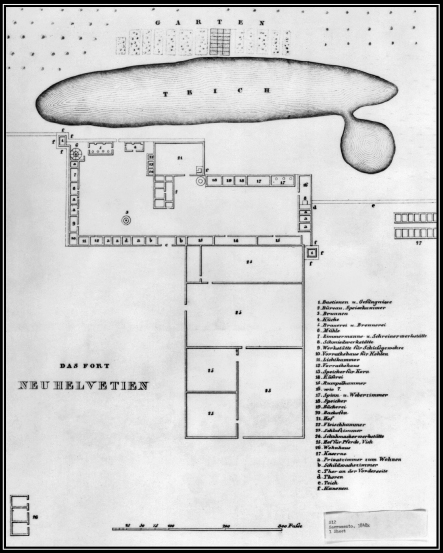

Sutter naturally made sure that the fort contained a distillery and brewery, or what Heinrich Kuenzel coined “Brauerei u. Brennerei” in his 1849 map of the fort. Used between 1844 and 1846 and standing two stories in height (roughly sixty feet by twenty-five feet), the distillery was fed with grapes picked by Sutter’s Nisenan and Kanaka slaves along the area’s lush riverbanks and wetlands.38 The pickings were mashed and fermented into whiskey barrels, with the mash then being distilled into brandy. According to archaeological digs done between 1950 and 1960, the compound may have contained up to four stills. Operations were halted, however, as a result of Sutter’s inability to keep the understandably popular elixir safe from several fort inhabitants and a handful of area natives.39

German-born Heinrich Lienhard had a lot to say about John Sutter’s drinking habits and the haphazard prospects of gambling in early California. California State Library.

Sacramento’s first brewery, established in the early spring of 1849, was located adjacent to Fort Sutter, just at the corner of M and Twenty-eighth Streets. As stated in a Placer Times advertisement, “P. Cadel and Company” boasted “the best quality of Ale and Beer.”40 The brewery’s founder, Peter Cadel, was from Baden, Germany, having settled in Sacramento in 1846, originally as a dairyman in Sutterville. Traveler J. Goldsborough Bruff provided an account in December 1850 of Cadel’s new brewery in stating that “within a few hundred yards of the [Sacramento Hospital] are several neat frame houses, one of which is a brewery, with a sign of ‘Galena Brewery’41 on it. We tested their ale and found it good,” with each glass priced at twenty-five cents.

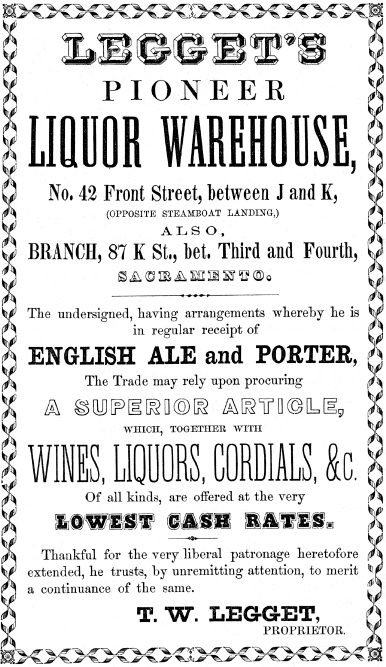

Cadel’s ales appear to have been the first of their kind brewed in the Sacramento area. Fermented rapidly via top-fermentation yeasts and at a high temperature (sixty to seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit), the natural sugar content remained unchanged, preserving a certain sweetness not found in lagers, which were made by bottom-fermentation yeasts and brewed for a longer period and at a cooler temperature. A notable figure in the spread of ale-style drinks in early Sacramento was Scotsman Thomas W. Legget, who established a public house of his own, Legget’s Ale House, on 42 Front Street in November 1852. He also operated the “No. 2 ale cellar” or “Branch No.2” at 87 K Street. It has been said that Legget enticed customers by saying, “There’s many an idea in a barrel of ale. Billie Shakespeare and Bobbie Burns didn’t drink for nothing.”42

Kuenzel’s 1849 map of Sutter’s Fort. Brewery and distilling facilities were located in the fort’s northwest corner, near the blockhouse. California State Library.

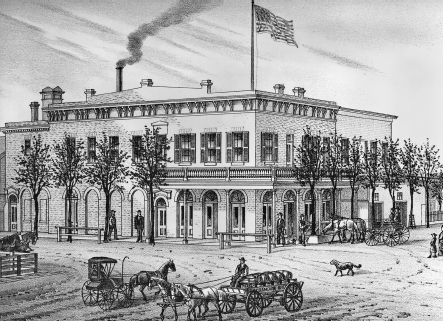

Cadel decided to rent out the brewery in 1853 and then sold it to Philip Scheld for $2,000 in 1854. Under the new leadership, the operation became known as the Sacramento Brewery. Also a German, Scheld immigrated to America in 1845. Once in his hands, the brewery would flourish for the next three decades. As of 1860, it was two stories high, made of brick and possessed a basement for cooling and storage. At 120 feet long and 100 feet wide, it was large enough to cover two lots and, according to one source, was producing some 700 gallons of lager per day by 1855. Scheld’s fuel to burn, per round of brewing, included twenty-five thousand pounds of malt and three thousand pounds of barley, while the machinery running the brewery included both horsepower for the malt mill and a windmill for the use of water. As of 1858, Scheld was making an average of 3,500 gallons of beer per week, with distribution to nearly thirty saloons throughout the city.43

An advertisement from the 1856 City Directory for Thomas Leggett’s ale business, one of Sacramento’s earliest alcohol retailers. Sacramento Public Library.

Primeval Sutter’s Fort, the location of some of California’s earliest breweries. Center for Sacramento History.

As mentioned earlier, the rise of area beer production did so under the most ideal of conditions. Between 1850 and 1860, barley production rose sharply from roughly 3,000 bushels to just over 514,000 bushels, making Sacramento County the leading barley producer in the state for the latter year.44 Yolo County’s strain of barley followed in similar fashion, “particularly on the banks of Cache Creek,” and was referred to by the Union as a most “precocious grain.” By 1858, the city’s breweries were consuming 502 tons of barley a year in the production of beer.45 As for hops, they grew aplenty near present-day Sacramento State University. Originally known as Brighton, at mid-century, the area contained California’s most extensive hops fields.46 An additional source of seed and grains was Smith’s Pomological Gardens and Nursery. Founded by A.P. (Anthony) Smith in 1849, the gardens were located just north of the present-day East Sacramento district of Sacramento but south of the American River. Smith produced fruit and vegetable seeds from his fifty-acre site that, in spite of being attacked by a “plague of locusts” in the summer of 1855, had doubled in size by 1858.47

The Sacramento Brewery, opened by Peter Cadel, was the city’s first known brewery specializing in ales. Sacramento Public Library.

There were other factors enhancing Sacramento’s ability to brew. The allure of the Gold Rush, coupled with the failed European Revolutions of 1848, created a stream of immigrants, particularly Germans and Frenchmen, who possessed a near-biological acumen for beer production. The presence of Irishmen, searching for gold while also fleeing moribund economic conditions in their own country after 1840, further increased the supply of knowledgeable beer makers. A quick scan of 1850’s census reveals not more than six individuals claiming to be brewers.48 Three were German, two were from Massachusetts and one was French. The Frenchman, George Zins, and one of the Germans, George Weiser, collaborated in 1850 to construct their own brewery at Twenty-ninth and J.

Other early Sacramento brewers of European origin were the Germanic Schildknecht and Koester, whose names appear in the 1851 Directory.49 According to the publication, their brewery would have been situated on Front Street, between F and G (also referred to as Sacramento and Broad, respectively). Although short-lived, another business, the United States Brewery, was located on K Street, between Eighth and Ninth in the summer of 1851. It produced ale, as it claimed, with an “excellence and cheapness unsurpassed.”50

Possessing more of a muted presence was wine, whose California genesis rests in the cultivation—by early Spanish missions—of grapes for the creation of the symbolic blood of Christ for the Eucharistic liturgy, a process that dates back to the arrival in California of Catholic missionaries in the late seventeenth century. As for Sacramento, an advertisement in the March 19, 1851 Transcript declares, “GRAPE CUTTINGS!! GRAPE CUTTINGS!! from the celebrated Vineyard of William Wolfskill for sale.”51 Another entry in the October 3, 1850 Transcript hails the $25,000 harvest from General Vallejo’s Sonoma vineyard, a parcel of land covering not more than an acre.52 Even Captain Sutter, in an attempt to vault his way out of debt, advertised the sale of his prized vines at Hock Farm. Akin to the production of beer, all boded well for the growth of Central Valley viticulture, and by 1853, California would become the leading producer of wine in the country at 58,055 gallons per year.53

Now that we have explored one element that brought saloons to Sacramento and kept them there, let us take a look beyond Slater’s barroom or the Stinking Tent and at some of the city’s other drinking spots. One dispatch from an unknown 49er provides a glimpse of the city’s gambling and drinking culture in December 1850: “Sacramento is the liveliest place I ever saw…about every tent is a gambling house and it made my head swim to see money flying around.”54 Another superb depiction comes from New York Tribune journalist Bayard Taylor, whose travels throughout the West yielded a treasure-trove of cultural description. He states, “Sacramento City was one place by day and another by night; and of the two, its night side was the peculiar.”55 He adds that as a miner made his way through nocturnal Sacramento, there was the following to see:

In the more frequented streets, where drinking and gambling had full swing, there was a partial light, streaming out through doors and crimson window-curtains, to guide his steps.

The door of many a gambling-hell on the levee…stands invitingly open; the wail of torture from innumerable musical instruments peals from all quarters through the fog and darkness.

The gentleman who played the flute in the next room to yours at home has been hired at an ounce a night (gold dust) to perform in the drinking-tent across the way.56

Well-traveled journalist Bayard Taylor provided some of the first descriptions of Sacramento’s early Ersatz-style saloons. Library of Congress.

The most famous and versatile of this next generation of saloons was the Round Tent. Established in late July 1849, “first on J between Front and Second streets and afterwards on Front between I and J,” the saloon could claim direct lineage to the Stinking Tent.57 As Richard DeArment states, “A group of sharpers took over [Lee’s] Stinking Tent, changing the name to the Round Tent.”58 Those “sharpers” were Zaddock Hubbard and Gates Brown. From its inception, the Round Tent was a gaming mecca. As a young miner, William Johnston’s view of Sacramento’s “one great gambling rendezvous” matched that of “a circus-like affair of mammoth proportions, capable of accommodating one hundred or more persons.”59 Morse’s take on the Tent is a bit less complimentary:

Music and a decorated bar and obscene pictures were the great attractions that lined this whirlpool of fortune and coerced into the vortex of penury and disgrace many an American who had come to California without his morals or the decencies which he was taught at home…toilers of the country, including traders, mechanics, miners and speculators, lawyers, doctors and ministers, concentrated at this gambling focus like flying insects around a lighted candle at night; and like such insects seldom left the delusive glare until scorched and consumed by the watch fires of destruction.60

While Morse, generally thin on the establishment’s physical description, recounts the Tent’s being fifty feet in diameter, Johnston tells us that the “interior revealed two large tables at which the Mexican game of monte was being played.”61 He also describes ornate roulette tables, accompanied by bankers “with pleasant, smiling heaps of gold and silver beside them, so arranged to be enticing to their expecting customers.”62 Johnston goes on to paint the bar area as a “conspicuous feature…decorated with large and costly mirrors, behind shelves adorned with a glittery array of decanters containing sparkling liquors…there were extraordinary pyramids of lemons, towering peaks of Havana cigars and gorgeous vases containing peppermint. A bevy of patrons thronged this attractive bar and there was a constant clicking of glasses, popping of corks, amid the gurgling sound of tut, tut, tut, etc., etc., etc.”63

This early rendering of Front Street, between I and J Streets, features both the Eagle Theater and the Round Tent Saloon. Center for Sacramento History.

In 1850, miner William Swain described the Round Tent as “a place made of a huge circular tent, like a small circus and emblazoned with large letters ‘City Diggins.’ This during the day is almost unoccupied, but at night music rings out and it is to excess crowded.”64 Vouching Swain’s claim is a short entry in the Placer Times in October 1849 that describes performances by the California Ethiopian Serenaders at the tent “to full houses and much to the amusement of people generally.”65

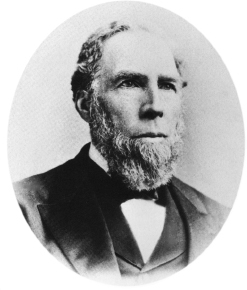

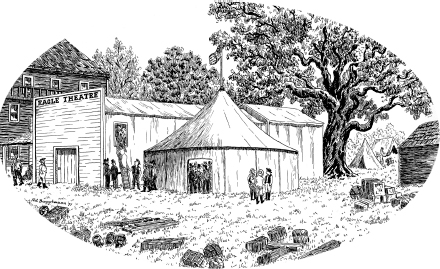

The Round Tent’s outward appearance was as follows: the base was rounded, while the sides rose from dirt floors to a pointed crescendo, which was topped off with a flag. This profile’s source is George Victor Cooper’s 1849 lithograph, a valuable tool for pinpointing several key landmarks in early Sacramento. An additional description of the Tent comes from miner William Redmond Ryan, who recalled the tent to be “thirty feet in diameter, by twenty-five in height, from the conical top of which floats a large red flag inscribed with the words ‘Miner’s Exchange.’”66 Ryan also recounts six or eight large gambling tables, “each…let out at the nightly rental of twelve dollars.” The Tent’s bar was positioned “opposite the door, where large profits are realized upon refreshments sold to the players and strangers.” Insofar as a builder, “it is probable that [Albion C.] Sweetser…constructed the long-remembered ‘Round Tent.’” Sweetser was a native of Maine and became known for doing some of the earliest professional designing and building in the California territory, one method being the use of “willow poles for structural parts and canvas and tarred paper for roofing and wall coverings.”67 It’s ironic, however, that the builder of one of the city’s most notorious drinking and gaming spots was also an ardent teetotaler.

Early Sacramento contractor Albion Sweetser very likely manufactured the Round Tent Saloon and its attachment to the Eagle Theater. California State Library.

A true legend of the Round Tent was Lucky Bill Thornton (also referred to in some sources as Thorington). A native of New York State, Thornton jumped a California-bound wagon train in the late 1840s. Deposited in Sacramento, Thornton would come to choose none other than the Round Tent to introduce to the river city his specialty: the shell game. Lying in wait, he positioned himself in squat near the entrance to the Round Tent, where laid out before him was a sleek board and three halved walnut shells. With the charm of a cavalier and wielding an uncanny sleight of hand, Bill worked wonders. His “Lucky” sobriquet proved a total misnomer, however, as he was an unrepentant cheater. In addition to the cork-shaped pea, seemingly the only one visible to players, he maintained an additional pea under a nail on one of his swiftly moving fingers. The trickster would release his duplicate pea whenever needed to negate an “on the square” selection. Bill also used “cappers,” gamblers who were planted to “win” on occasion, so as to lure wide-eyed neophytes. So effective was Thornton’s charade that, in just a few months, he was able to extract $24,000 from the good people of Sacramento.68 Because his heavy addiction to faro, penchant for pretty girls and prodigious spending habits demanded that Bill keep producing gaudy sums, he was forced to seek fortunes elsewhere.

G.V. Cooper’s 1849 lithograph provides a choice view of the Eagle Theater, the tip of the Round Tent Saloon (E). Library of Congress.

Music was a standard saloon offering, or in the case of the Tent, a “noticeable feature” of a “modest string band seated on an elevated bench; the forerunner of those great orchestras which but a few months later became so marked a feature in the gambling saloons of California.”69 Hubbard and Brown would come to follow the lead of many East Coast saloons by introducing live theater. The concept of the “concert saloon” was likely born out of a similar movement that sprang out of England in the late 1840s. The primary goal was to keep patrons in a drinking mood by the expansion of entertainment options, which ranged from theatrical skits and magic shows to circus-type acts.

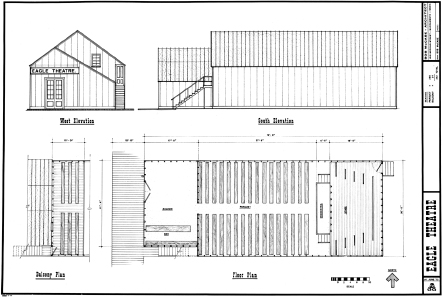

Once the Round Tent resolved to go forth with the “concert saloon” model, the Eagle Theater was born. Not only would the Eagle be the first public building in Sacramento, but as of July 1849, it also claimed distinction as California’s first theater. Situated on the corner of J and Front Streets and constructed with a patchwork of materials—wood, canvas and tin—the Eagle was large. According to historian Charles Hume, it could hold up to three hundred patrons, with its overall dimensions being some seventy-five feet by twenty-six feet in size. It also possessed a balcony area that could hold from sixty to seventy people.70 Entry to the theater, by most accounts, seems to have come via the saloon section of the Round Tent, where tickets would have been purchased at the bar, while actors’ dressing rooms were constructed out of the “packing boxes that transported the bar and trappings of the Round Tent Saloon.”71 The Eagle also seems to have possessed a saloon area of its own, accessible from the Front Street side of the theater.

When the theater opened for dance and choir performances in late September, the Placer Times declared, “In the main, the Eagle Theatre is all we may look for under the circumstances and as a respectable place of amusement, is entitled to the ‘full blast’ of amusement.”72 Despite its early successes, the theater quickly slipped into financial trouble. Attendance ebbed, with creditors eventually forcing Hubbard to cede “the saloon building in front of the…theatre with the entire stock of liquors, furniture and fixtures thereto belonging with the lease for the ground on which said saloon stands reserving to the said theatre the right of entrance through said saloon to theatre.”73 Exacerbating Hubbard’s travails was severe illness, so dire that official records from Sacramento’s Court of First Instance describe “Mr. Hubbard not being in his right mind.”74 With Hubbard gone by the end of October, the theater was sold to S. Clinton Hastings and Samuel Bruce, with William Hargrove assuming ownership of the Round Tent for the price of $4,075.

Elevations of California’s first theater and eventual concert saloon, the Eagle Theater, located at Front and J Streets. Center for Sacramento History.

The resulting inventory of the theater and saloon’s contents provides an interesting window into the Eagle and Tent: two mirrors, one clock, ten decanters, two dozen goblets, four dozen wine glasses, two dozen cordials, one can of peaches, one dozen mugs, one bottle of bitters, fifteen gallons of brandy, twenty gallons of liquor, six chandeliers, two small mirrors, one iron safe, twenty-one lamps, one gold scale, two tables, one dozen plates, one dozen soup plates, four settees (sofas), one box of raisins, one dozen cans of peas and one set of scenery.75 An additional list of items, purchased from Jones and Company for $309 by Hubbard, Brown and Company but never paid for, included thirty-eight gallons of gin, three large dishes, two dozen oysters and one thousand cigars, spelled “sigars” in the legal record.76 We also know from county court records that the barkeepers at the Round Tent were paid roughly $12 a day for their services.

With the movement of the Eagle from Front to Second and then taking on the name of the Tehama, did its saloon simply go away? The physical nature of both the Round Tent and the Stinking Tent made it easy for proprietors to literally fold up shop and speedily move to a new location. Giving credence to the Tent’s living well into 1850 was this from the August 13 Sacramento Transcript: “OLD ROUND TENT—The proprietors will sell the above tent and fixtures at a reasonable rate, as they intend to leave soon. The Old Round Tent is so well known, commendation is unnecessary. Those who wish to purchase will do well to call soon. BAKER & WEEKES.”77 The Tent’s run had ended. The competition, something that the saloon worried little about at first, had become a factor.

Hubbard’s efforts with the Tent were meaningful. In spite of a sporadic lifespan, the Round Tent and the Eagle fit the loose definition of a modern-day casino, offering gambling, drink, food and onstage entertainment. Moreover, from a cultural standpoint, Hume includes an important point in understanding the market demands for a place like the Eagle: “The audiences of this early theater were not ignorant boobies who might appreciate anything put on the boards, but instead were men who were used to attending the theater at home and were anxious to resume the cultural experiences that they had left behind.”78

The Tent’s allure also served as a cultural nexus for the Gold Rush’s varied nations and races as, in Johnston’s words, it drew “various nationalities…noticeable on account of peculiarities of dress,” which included “beside those whom we call Americans: Mexicans and native Californians, men from many of the South American States and from numerous islands of the Pacific.”79 One Englishman had much to say about the city’s diverse gaming clientele: “The most mixed and motley congregations, white, half-castes, copper, mahogany and black.” He continues, “The cloaked Spaniard and the phlegmatic German laid down their stakes and stood back from the circle, revealing nothing. The Chinese were the most innocent-looking and the best gamblers. Their bland and baby-like faces looked serene, win or lose.”80

An inventory of the City Hospital wards in the winter of 1850 further shows the increasingly diverse racial and ethnic flavor of the entire city: “6 English, 1 Switzerland, 1 Wales, 1 India, 1 Australia, 2 Holland, 3 Belgium, 1 Azores, 1 Holstein, 7 France, 19 Ireland, 1 Sandwich Islands, 1 Sweden, 1 Norway, 2 New South Wales, 1 Singapore, 5 Mexico, 2 Hungary, 6 Scotland, 17 Germany, 479 United States.”81

The Tent as a congress of multiple cultures is a fascinating one. Outside the mines, it is difficult to think of any other place where this kind of integration could have occurred. While racism was indeed prevalent and exacerbated by inevitable gold field jealousies, the saloon at least forced the races to commingle and interact within a simple social setting. This alone makes the Tent’s role—as well as that of the general saloon—in Sacramento’s social evolution a significant one.

What happened to the man who gave birth to the Tent and Eagle? Hubbard attempted to open a type of eatery/saloon called “Hubbard’s Exchange,” located on Front Street between K and L Streets. The June 6, 1850 Sacramento Transcript was the first to get word out: “This establishment has been newly refitted under the superintendence of the old proprietor, Mr. Hubbard, who will be glad to visit with friends and assures them they will find the very best liquors and attentive attendants.”82 However, not long after opening, the enterprise went under, as did another chapter in Hubbard’s moribund business career.

Lucky Bill, who couldn’t fight the allure of so many naïve miners peppering the Mother Lode, left Sacramento in 1851. In and out of trouble and California for the next few years, Thornton eventually went clean, settling in Nevada’s Carson Valley near the town of Genoa. There, he found prosperity and respect through the operation of a ranch that was fitted with several thousand head of cattle. Unfortunately for Thornton, old habits fell hard. For crimes of murder and cattle theft, he found his ultimate demise at the end of a hangman’s noose in June 1858. It is said that in facing his impending execution, Thornton spoke these final, cool words: “Gentlemen, your executioner seems nervous. Permit me to put the noose around my own neck.”83

This twentieth-century rendering of the Round Tent Saloon was done by Sacramento historian Ted Baggelmann. Sacramento Public Library.

In spite of being dominated by the Round Tent, other saloons broke into the Sacramento market, primarily along the western end of J Street. Two such places, the Plains and the Shades, were mentioned by news writer W.A. George in a February 12, 1850 dispatch to the Missouri Republican as two of Sacramento’s “many gambling houses.”84 Hubert Bancroft described the Plains as fittingly adorning its walls “with scenic illustrations of the route across the continent.”85 Bayard Taylor described the extensive mural:

Some Western artist, who came across the country, adorned its walls with scenic illustrations of the route, such as Independence Rock, the Sweet-Water Valley, Fort Laramie, Wind River Mountains, etc. There was one of a pass in the Sierra Nevada, on the Carson River route. A wagon and team were represented as coming down the side of a hill, so nearly perpendicular that it seemed no earthly power could prevent them from making but a single fall from the summit to the valley. These particular oxen, however, were happily independent of gravitation and whisked their tails in the face of the zenith, as they marched slowly down.86

The Shades’ identity as a Sacramento saloon is an elusive one. Its sole mention appears in the July 20, 1849 Placer Times, which, in extolling the growth of Sacramento, stated, “You may purchase your breakfast at the Washington market, dine at Sweeny’s and drink your glass at the Shades.”87

If the appearance of every “golden age” requires an usher, the collective spirit of Sutter’s Fort, the Stinking Tent, the Round Tent and various others proved to be that very thing for Sacramento and the saloon. Each of these early establishments created an identity of escape and leisure that, when set against the backdrop of an infantile frontier town and a near-pathological grab for gold, merely set the stage for so much more to come.