Chapter 3

GIVE US YOUR GREEDY, GREEN AND LONELY: 1850–52

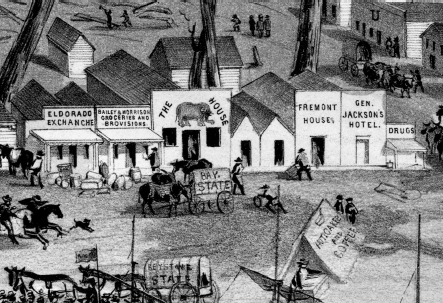

By early 1850, the heart of Sacramento’s saloon “district” was settling in near the intersection of Front and J Streets—and not solely on the merits of the Round Tent, which was months away from being packed up and sold. Whimsical monikers like the Elephant House, Mansion House and Empire would soon roll off the tongues of giddy Argonauts. All three upstarts stood near shoulder to shoulder to the south of the Round Tent, on J and Front Streets. A passage from the May 28, 1893 San Francisco Call paints a vivid picture of Sacramento’s Gold Rush saloon hub: “Gambling houses occupied prominent places on both sides of J Street and part of K, from the waterfront to Seventh Street and the sidewalk were encumbered with the tables of three card monte sharps and stands of other swindling games. From 12 o’clock in the day until past midnight the street gamblers plied their rascally arts along the thoroughfares.”88

The Mansion House possessed rather chaste origins. Situated at the corner of Front and J, the building had been home to Sam Brannan’s original mercantile, also considered by many to be the first framed structure in Sacramento. It should not surprise that Brannan, successful as a merchant and land speculator, grew into quite a gambler. So good was Brannan that he was known to have placed $10,000 in gold dust on a single hand and $18,000 on a single roll of roulette, winning both.89 Additionally, his well-deserved reputation for enjoying wine and women is expressed in a Salt Lake Daily Tribune story from 1877: “Samuel was a sly old boy and lusted after fair maidens, matrons, or even widows of Zion.” It goes on to say, “Samuel grew fat in the land of Gomorrah and in the hours of his prosperity became filled in the spirit—not of the Holy Ghost, but the spirits of Bourbon.”90 While it is easy to acknowledge Brannan’s being more than a business match for Sutter, how likely would it be that the city’s two most prominent figures/founders turned out to possess the loosest of morals?

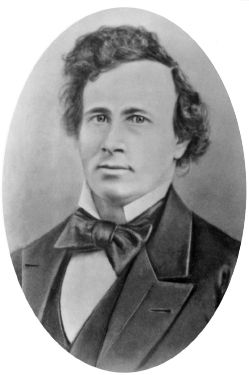

Energetic “Jack Mormon” Samuel Brannan wasn’t to be denied in his bid to make Sacramento a commercial hub. He also enjoyed drinking, gambling and rowdiness. California State Library.

However, in 1849, business came first for Brannan, who seldom hesitated to liquidate property, which he did with his riverfront store. By December of the same year, the Mansion House (née Brannan Mercantile) was in place. Its manager was Edwin Waller, a Texan who was in his late twenties. Waller’s associates included barkeeper Michael Brannan from New York (no relation to Sam), also in his twenties, and elder barkeeper Joseph Reynolds, who was in his late fifties and from Missouri. The person of Edwin Waller is curious from a biographical standpoint. Based on census information from the states of California and Texas, it’s probable that he was a major in the Second Texas Cavalry in 1861. Between 1862 and 1865, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Thirteenth Texas Cavalry Battalion. In this capacity, he conducted partisan activities in southern and western Louisiana and eventually participated with Confederate units in the battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill.

In many ways, the Mansion House was a typical Gold Rush saloon. There were crazed dogs. Yes, “a dog, supposed to be mad” rushed into the House “foaming at the mouth and snapping at everything it could reach.” After clearing the saloon, Waller picked up a Colt revolver and shot the dog. Save for the animal, no injuries were recorded.91 There were gunfights. A few months later, the August 5, 1850 Sacramento Transcript would recount the deranged and drunken actions of a Brannan; in this case, John (no relation to either Sam or Michael). After being tossed two times from the saloon, the aggressor returned with gun in hand. Having been forewarned of Brannan’s designs, the Mansion House’s barkeep that night, a Mr. Winters, stood in wait with a firearm as well. When Brannan entered the saloon, the employee took aim and delivered a nonfatal shot into the “fleshy part” of the renegade miner’s thigh, leaving him incapacitated and ready for arrest.92

Finally and perhaps most significantly, there were disputes over honest play. It was two o’clock in the afternoon in late February 1851. Although days from being outlawed, the practice of placing gaming tables upon the sidewalks outside their businesses was still embraced by owners. Seated at one table was Frederick J. Roe a young Englishman, gambler and dealer.

French monte was the game, one that maintained a dubious reputation for being easy to fix. Accordingly, one of the spectators, a miner, was suspicious of play and brazen enough to say so. In response, the intoxicated Roe recoiled with what equated to “play or go.”93 After the miner instructed Roe to “go to hell,” a fistfight erupted, one that Roe and three allies were winning with a huge crowd watching.94 Charles Myers, a local wheelwright from Columbus, Ohio, who could not “stand and see such things going on, without lending [his] assistance,” intervened, throwing Roe to the ground and exclaiming, “For God’s sake…if you want to fight, now have a fair fight and don’t three or four of you jump on the poor devil and kill him in the street because he has no friends.”95 Seconds later, Roe jumped to his feet and, hunched over, searched the crowd for Myers. After spotting him, Roe snarled, “There is the damned son of a bitch that held me.”96 Roe then pulled a gun, steadied himself and aimed it toward Myers’s head. In response, the wheelwright fled toward the Mansion House for safety, but to no avail. Roe pulled the trigger.

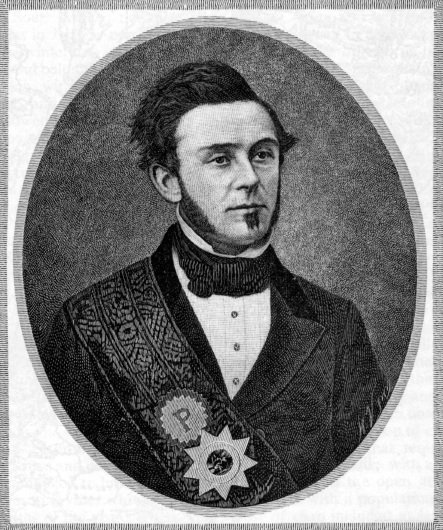

G.V. Cooper’s 1849 lithograph of Sacramento’s J and Front Street hub shows the Mansion House (T) and Empire (S) and Gondola (Q) saloons. Library of Congress.

After the ball entered Myers’s head “just in front of the left ear and passed into the lower part of the brain,” his limp, soon-to-be lifeless body fell to the dusty ground.97 Observers recount, at this point, an atmosphere of shocked silence. The ostensible peacemaker, described by the Transcript as a “quiet and most respectable citizen,” had been struck down both violently and suddenly.98 Rolls in the dust, fisticuffs and other forms of generally innocuous violence were common during the early Gold Rush, but Roe’s actions were not just mortifying to those who saw them—they were astonishingly new.

What a dramatic moment it must have been. Myers’s body was lifted into the air and carried down Front Street and then up K Street to the blacksmith shop of a former partner of the wheelwright’s, Joseph Praeder, a thirty-three-year-old Pennsylvanian. Upon arrival, Myers’s body was examined and his wounds determined mortal. The likely examiner was thirty-two-year-old J.M. MacKenzie, city councilman, physician and fellow Ohio native. After hopping atop a wagon and decrying the deplorable state of affairs in which “citizens were shot down in daylight,” MacKenzie went on to demand an investigation and strong punishment. The words quickly fomented the crowd into a frenzied mob that demanded nothing short of a lynching.99

With word spreading throughout the central city, other crowds were born, all drifting toward Roe’s holding place, the police station on the corner of Second and J Streets. A number of attempts were made to quell the masses, including one by City Marshal N.C. Cunningham, who committed himself to letting justice take its course. It appears to have been at this moment that those in favor of informal justice formed their own committee. Distinguishing himself as the marshal’s moral opposite—at least for a short period of time—was Dr. Gustavus Taylor, who, after examining Roe and ostensibly vouching for his safety, faced the crowd and helped seal the prisoner’s fate: “Half an hour—if a decision is not made in that time I will head the crowd and take the prisoner out. A peaceable man has been shot down. If those who are now guarding the prisoner meant to shed blood, let it be so. The people are supreme and will be so now.”100

It is not known whether Roe ever scoffed at Taylor’s presence, but something had indeed affected the latter’s attitude, very likely Roe’s intoxication. Regardless, Taylor was pivotal in swaying the mob, now numbering some two thousand. With minutes passing, Taylor again chose to speak. The Transcript reported, “Taylor called on every citizen to arm himself. If the officers of the law thought proper to interfere and seek to protect the prisoner, when the jury had decided on the case, then said Dr. T., let the streets of Sacramento be again deluged with the blood of her citizens. Dr. T. was ready to sacrifice his own life, if necessary, to carry out the ends of justice.”101

While Taylor ratcheted up the crowd’s ire, the committee that represented the mob tried to conduct a somewhat formalized review of the facts. At this point, a bizarre twist took place: Roe was sobering up. This, combined with the arguments of those admonishing formalized, legal action, started to sway Taylor, who then asked the mob to reconsider. The crowd, now nearing five thousand, would have no part of it. Taylor was out, and moments later, with the mob hitting critical mass, a large wooden awning was torn down and used as a battering ram. Soon after, the jail was breached and Roe taken to Sixth Street, between K and L, an area known for its patch of tall oaks. It was 9:30 in the evening, and Roe’s benediction was contrite. He blamed “sudden impulse” for his actions and then, after drinking a glass of water, pleaded that “God have mercy on [his] soul.”102 Nearly eight hours after pulling a trigger at the Mansion House, young Frederick Roe was hanging from an oak tree. Making a strange tale even stranger is the fact that Myers did not pass until Roe was dead.

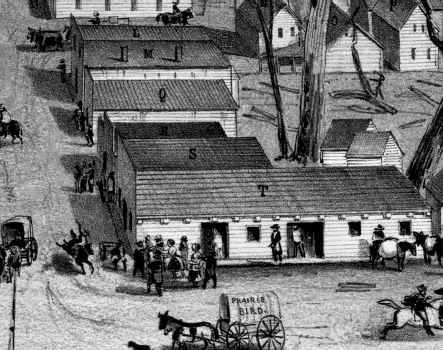

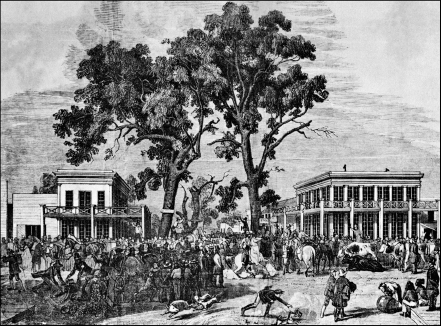

English gambler Frederick Roe was likely hanged from one of the tall oaks in the pictured Horse Market. Sacramento Public Library.

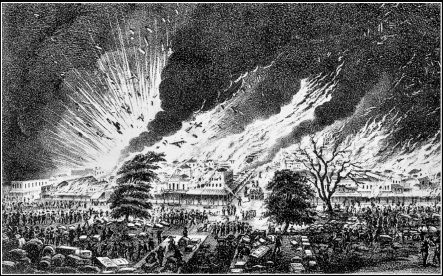

The Myers murder and Roe lynching occurred at a time when violence in Sacramento was on the rise. Shootings, robberies and muggings were all surging, and the citizenry’s collective angst grew in kind. A sampling of this rising concern comes from the January 14, 1851 Transcript: “Within the last two months, there has been a fearful increase of crime throughout the entire length and breadth of our state. It is with difficulty, at times, that the inhabitants of our cities and larger towns are restrained from returning to that prompt and efficacious mode of suppressing crime, known as the Lynch law.”103

In this regard, the significance of Roe’s crime is remarkable. It was a watershed of sorts, where Sacramentans’ morality and perceived concept of community would be put to a very severe test. Would formal justice be given a chance to sort through events and satisfy the community it served, or would the caprices of vigilantism and mob rule win out? In this case, the absence of any meaningful trust in the government’s ability to solve problems meant that those who knew better, or felt they did, wrested control. The Transcript describes the vigilante committee as consisting of “some of the most prominent and respectable men in the city.”104 It was also composed, overwhelmingly, of merchants (nine of the fourteen) whose interests were elementary: safe streets brought patrons, and patrons meant profit.

For the common citizenry, the incident symbolized something other than good business. With the affair occurring nearly a year after the city’s incorporation and with a legal system indeed in place, it was clear that the public’s acceptance of organized rule needed considerable seasoning, a state not unique to Sacramento. A brief scan of the Union in days following the Myers murder reveals numerous lynching-related headlines: “Lynching Again,” “Tragic Affair in Napa City—Murder and Probable Lynching” and “Another Man Hung!”105 As statistics bear out, early Californians neither trusted existing legal institutions to be effective nor considered the repercussions of their own illegal actions. Between 1849 and 1853, the state experienced just over two hundred lynchings, whereas just a few years later, between 1859 and 1863, lynchings dropped to just under twenty.106 Historian David Johnson offers the following interpretation of such figures: “The legitimacy enjoyed by these popular tribunals stemmed from the moral authority that Californians, like other Americans of their era, gave to the ‘people’ over the coercive power of the state.” He continues by stating that the contemporary perceptions of ad hoc justice were “not described as the rage of an individual, but as that of the people taken as a single sovereign and in this respect rage and excitement served as an unerring sign that society’s moral sensibility had been violated. Such outrage spoke to an inherent, natural understanding of justice, unreachable through the procedures of due process.”107

The role of the Mansion House in the tragedy is also worthy of discussion. If it’s true that Roe’s repentance came after sobering up, the responsibility of the saloon as the germ of his murderous malaise is clear. Moreover, his drunken state and later change of heart certainly affected Taylor’s moral compass; it is then feasible, based on this and certainly to those from the temperance camp, that Roe would not have murdered Myers without the aid of spirits. A curious notion in this regard is the absence of any temperance-minded comment regarding the event. Roe was drunk at the time of the killing; various citizens attested to this. Yet why did the anti-alcohol elements of the city not convert the incident into even the smallest degree of moral leverage? While we don’t know for sure, it is likely that saloons simply proved too strong a presence in the city’s political, social and economic life for the area’s diminutive guard of teetotalers to make any impact. In other words, political clout soundly trumped moral clout in an environment where the saloon was responsible for so much that kept a city both smiling and solvent.

One of the Mansion’s immediate neighbors was the Empire, described by one observer as “an immense room filled with gamblers and revelers.”108 Horace Bell, a visitor to Sacramento City during the summer of 1850, recalled a stroll down J Street as revealing “at every block…gambling houses in full blast, but all of inferior note, until you reached the Empire.”109 The saloon was located at 104 J, and compared to its immediate neighbors, it was tamer and even a bit more upscale. The fullest description of the Empire’s size and décor comes from the June 26, 1850 Transcript:

The Empire Saloon is 75 feet by 55, giving an area to the floor of 4,125 feet. Both rooms present a magnificent appearance when lighted. Almost the entire front of the Empire consists of heavy doors, which being thrown open give to the room an elegant and inviting aspect. In the rear is a fine dining saloon, under the direction of Mr. Jackson.

This establishment is kept after the manner of the first hotels of the States and it is certainly creditable to all concerned. Back of the dining room is a room elegantly furnished with mirrors, lounges, etc. The room is intended for private parties.

The Empire Saloon certainly bear[s] the palm all the other establishments in the city.110

Albeit so close to what symbolized Sacramento’s grittier side in the Mansion, the Empire would be both more spacious and more elegant. Its dining area and private room meant that the Empire’s business objectives were to be more diversified than its neighbors. According to the 1850 census, it maintained a large staff, including six waiters and four barkeepers.111 The Empire also delivered top-flight entertainment, with its biggest headliner being the Tyrolese Singers. As indicated by their title, the quartet, consisting of two men and two women, came from Tyrol, a section of central Europe bracketed by Switzerland, Austria and Italy. A most flowery description of their debut, coinciding with the opening night of the Empire itself, tells us that “there was a perfect jam to hear the Tyrolese Singers, whose fame had preceded them…Dressed in a costume from their own clime, they attracted great attention; and when they concluded their first song, there was a strong manifestation for a continuance. Each of the singers wears a hat of the sugar loaf order, decked with ribbons.”112

At this time, groups of various talent levels adorned many of the city’s saloons within which “full bands, or choice musicians are engaged, whose discourse music the evening long.”113 The Empire maintained one of the best. One September 1850 newspaper review called the Empire’s musicians “a crack band, whose music is worth going to hear.”114 Illinois physician Israel Shipman Pelton Lord invokes the Empire’s power of musical persuasion with a lively description of “a brass band from their high ‘vantage’ ground, a balcony at one end, inciting them to madness.”115

The obvious value of music within the saloon milieu segues us toward its strange absence between late August and late September 1850. A comprehensive search of public and private records reveals little insight into the oddity. It was announced in the August 29 Transcript that “the musicians of the city, whose sweet strains were heard in almost every saloon, have been allowed to retire, or in other words, music has been dispensed with by proprietors of the saloons. The blowers of trumpets, agile-fingered pianists and scientific ‘fiddlers’ were on a regular ‘fiddle-dee-dum’ on Tuesday night and the streets resounded with music from the grave to be funny.”116

A possible clue may reside in the collective cacophony of so many saloons creating noise. An account from German novelist and traveler Friedrich Gerstäcker speaks to his experiences as a trained musician who, when arriving in Sacramento, was told by “American” saloon owners that all they wanted was noise. Gerstäcker continues, “And as these hells in some streets stood house by house, or rather tent by tent, the reader may judge what a deafening mass of sounds continually floated through the air.”117 Yet weeks later, and most relevant to the quality of talent at the Empire, readers of the Transcript were greeted with the news that “the advent of music once more in our Saloons seems to give general satisfaction. The splendid band that formerly played at the Empire have resumed their places and discourse their rich and accurately played pieces daily to hundreds of listeners.”118

The musical moratorium corresponds to no other event. The cholera epidemic was two to three weeks off from the recommencement of tunes, while neither fire nor flood seem to have been factors. A clue to understanding the nature of the ban, also found in the Transcript and in a blurb about the Oregon saloon, refers to the absence of music as an “experiment.”119

Again, G.V. Cooper’s 1849 effort shows us the Front Street destinations of the Elephant House and the El Dorado Exchange. Library of Congress.

Another notable stop for the Sacramento Argonaut was the Elephant House, which sat on Front between J and K Streets, just a few doors down from the Mansion House. If the miner were to speak of his participation in the Gold Rush, it was common to claim to have “seen the Elephant.” Painted on the false façade of the saloon was an elephant with the words “the” and “house” placed to each side, making itself easily visible from any ship anchored along the embarcadero. In addition to its saloon-style offerings, the House, with a front of 40 feet in length by 150 feet in depth, provided lodging with “three tiers of bunks on each side” of the house.120 Tenants paid a fee of $2.00 a night without food and fifty cents for a drink or cigar.

Adding to this original core, other saloons would establish strong names for themselves in this post–Round Tent era. Moving down J Street, one would encounter, in no particular order, the Oregon, Lee’s Exchange, the Magnolia, the Woodcock, the El Dorado, the Humboldt and the Orleans House. The Orleans, located on Second Street, between J and K, was the first of its kind for Sacramento: a riverside palace that offered a saloon and overnight accommodations, as well as billiards and a reading room. From the outside, the Orleans’s appearance was anything but subtle. Its multiple stories, handcrafted terrace overlooking Second Street and imposing façade made it one of the most impressive buildings in Sacramento and certainly the class of the city’s hotel/saloon community. With that said, who could have known that the wooden Orleans was prefabricated, brought “around the horn” from New Orleans and built for $100,000?

In its initial phase, the Orleans’s saloon opened on a Saturday evening in late March 1850. The Transcript describes the Orleans as “larger, more decorated and striking” than its rival, the El Dorado, which opened its doors concurrently to the Orleans. The Orleans’s walls were viewed to be “rich and adorned with splendid paper hangings” with one “continental picture, heavy with ornament.” Also adjoining the Orleans were “two splendid rooms…one containing several billiard tables and the other furnish[ing] an admirable retreat for gentlemen; newspapers, dominoes, checkers and backgammon can be found there, with which to while away the time.”121 While the Orleans’s first floor was occupied almost entirely by its saloon, the private rooms of the Orleans, which opened in mid-April, were located on its second floor and possessed the same style concept as the lower floor. Further detail on the Orleans’s spacious décor comes from a letter to the San Francisco Courier written by a recent visitor to the establishment, describing it as a building with “seventy-five rooms, capable of lodging one hundred and fifty persons. The tables in the dining saloon are extensive enough to admit two hundred persons at one meal.”122

Another interesting description of the Orleans comes from Lord, who, in October 1850, referred to the Orleans as having “an immense saloon in front and two very large rooms in back; one with three billiards tables and the other a sitting room, furnished with dominoes, chequer [sic] boards, chess men, etc. The walls of the saloon are covered with paper, exhibiting modern Grecian scenery, in connection with the Turkish War, South American, etc., really splendid. And here the gamblers most do congregate.”123

The Orleans’s deluxe accommodations were a far cry from those of Sacramento’s earliest saloons, which maintained the modest objective of simply making sure patrons could drink, gamble, smoke and be entertained within four walls, a ceiling and a floor. This earlier breed also catered to the scattered miner/laborer who, after a night out, would settle for the most basic of sleeping conditions, perhaps a bar top or a bedroll outdoors. By appearance alone, the Orleans sought to attract the higher strata of society, those living in the city as well as those passing through (e.g. politicians, merchants, professional gamblers). It also wielded a reputation for being “a favorite stopping place for celebrities of the day,” including starlet Lola Montez, about whom we will speak of later.124 In time, the Orleans became well placed within the nexus of Sacramento’s political, intellectual and financial aristocracy. This area of Second Street between J and K Streets would come to be called home by Wells Fargo and Company, the chambers of the State Supreme Court and the Sacramento Union. Also by this time, the hotel had ascended to the position of depot for Wells Fargo stage transport.

While an archetype of the glamorous, multipurpose saloon, the Orleans also holds the distinction of having been a frequent meeting place for both political and nonpolitical groups and causes. Formal governmental meetings to discuss amending the city charter, developing firefighting companies and building cisterns to more easily fight fires were all held at the Orleans. Local Democrats also met there in late April 1851, nominating party members for city positions. Perhaps the Orleans’s greatest moment came in February 1854, when the hotel welcomed local authorities to officially greet Governor John Bigler, state officers and members of the legislature with open arms. Sacramento was now the capital of California, with the Orleans House standing as the very first place of formal assembly for state officials within the river city.

Refined as it was, the Orleans entertained its share of shootouts and other affrays. One gentleman lost the “end of his nose” as a result of an airborne tumbler. Another row took place on November 3, 1852, between Roy Beam and Edward Eastbrooks. It rose from politics and deteriorated from there. When the smoke cleared, a Colt revolver had fired “four or five” shots, none of which found their mark, and according to the Union, “both parties were arrested and bound over.”125

In proximity to the Orleans was Lee’s Exchange, located at 46 J Street. It was the creation of Barton Lee, an early Sacramento real estate mogul, and built primarily as a saloon in early summer of 1850. It soon came to boast, much in the mold of the “concert saloon,” Lee’s Theatre Hall, a showcase for various forms of live entertainment. Despite one source accusing the Exchange’s band of turning out “barbarous” music, it formed a viable trump to the Empire’s musical prowess.126 Opening just months after the saloon, the “splendid Concert Room” on the Exchange’s second floor was reported to be “well ventilated and capable of seating twelve hundred people,” a notable figure when one considers that when full, the hall held nearly one-tenth of the city’s population.127 The hall was mostly constructed of brick, with rough dimensions of 60 feet by 120 feet. Popular acts to grace its stage included the New World Serenaders, the Sable Harmonists, the New York Serenaders, the Acrobat Brothers, the Ethiopian Serenaders and the Tyrolese Singers. A performance at the Exchange typically cost from two to five dollars per person.

Lord’s initial description of the Exchange’s “great saloon below the theatre” reveals a spot “finished up in a style that would astonish anything coming from beyond the Rocky Mountains.” The size of the saloon was notable, resting with dimensions of “100 feet by 75 and giving the superficial contents of 4,000 feet.”128 We also know that, at any given time, the Exchange could host as many as four hundred people who were “not at all in each other’s way.”129 Further description of the Exchange comes from Lord:

It is fitted up like a palace and has a dozen or more tables of all kinds of “games.” On one side is a counter, 30 feet long, behind which stands three fine looking young men dealing out death in the most inviting vehicles—sweet and sour and bitter and hot and cold and cool and raw and mixed.

Again—elevated above the mass site a band of musicians playing—ever playing for the amusement of the spectators and gamblers and to attract the passers by.

Occasionally a good song is sung. The walls are covered with pictures, many of them, men and women, almost or quite in a nude state. Everything is got up, arranged and conducted with a view to add to the mad excitement of gambling.130

Lord also mentions the wages of the Exchange’s gambling staff as being anywhere between seven and twelve dollars daily, plus board for their efforts.

Another account of the Exchange is a great deal less glowing. The Call described it as a “large gambling-hall of unsavory repute, where for a time swindling games of every description were in progress and where fights were of hourly occurrence.” The paper goes on to call it “the principal rendezvous of the three card, cup-and-ball and dice sharks. The liquors dispensed were vile and at night the hall was a pandemonium; but the air of lawlessness pervading the place was attractive to the reckless and half-drunken miner.”131

One of the more notable moments in the history of Lee’s Exchange occurred in June 1850, just days after the saloon’s opening, when Sam Brannan (yes, that Sam Brannan) and a group of friends entered the saloon to drink. Prior to their visit, Brannan had been seen pushing a comrade through city streets on a wheelbarrow while simultaneously beating a “Chinese gong.”132 After a lengthy period at the Exchange and “a little before daylight,” Brannan and his colleagues carried their revelry onto the Levee, where they—crowbars in hand—mounted an attack on a squatter’s hut.133 For their actions, Brannan and his retinue were found guilty, but the penalty—a fine of $200—proved a pittance for the affluent rabble-rouser.

A more amusing tale from the Exchange originated from an incident that took place in February 1851 and involved H.C. Norris and Louis Leclare.134 Over an unknown issue, Norris pulled a knife and Leclare a gun. However, just as the latter planned to fire, the ball rolled out of the pistol’s cylinder and fell to the ground. It is not known what happened after that, but the affray soon ended with Leclare departing (one can assume quickly) for the Crescent City Hotel, where he then ate supper. While there, Leclare received a challenge from Norris to duel that afternoon at three o’clock, which he accepted. However, even at this early stage in California’s legal development, dueling was an illegal activity, and the two were arrested.

The duel was a somewhat common fixture in early California’s saloon circles. Despite its illegality (as strictly outlined in the state constitution), everyone from politicians to miners often invoked the code duello. Historian William Secrest attributes the marked presence of dueling in California to the large number of southerners who chose to participate in the Gold Rush.135 Just as Europeans brought their beer, those from the American South imported their own cultural norms. In fact, more fatal duels took place between 1850 and 1860 in California than in any other part of the Union. Local churches attempted to discourage dueling by incorporating the topic into their sermons. The Reverend Osgood Church Wheeler spoke to a full house at the Baptist Church, located at the corner of Seventh and L, in early August 1852. The monologue amounted to an appeal for law enforcement officials to act more aggressively to enforce the anti-dueling laws already existing: “The laws we have are good enough and strong enough, if faithfully executed, to stop the evil in a single day. But laws unenforced are not only a shame and a disgrace; they are a decided curse to any people.”136

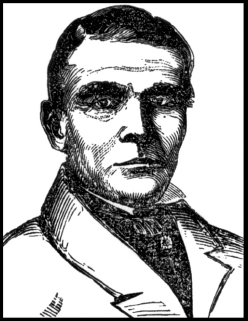

Baptist minister O.C. Wheeler came to Sacramento in 1852, only to find himself preaching against dueling and drinking. Sacramento Public Library.

While on the topic of cultural import, it bears mention that, for a time, Lee’s Exchange also was a venue for prizefighting. Born in the British Isles, bare-fisted sparring made its way into America in the early 1800s. Its function as a male testing ground meshed well with Sacramento’s Gold Rush demographics. As early as June 1850, the Transcript describes “Yankee Sullivan and his gentlemen” giving “displays of pugilistic skill” and states that “Mr. Sullivaa [sic] will be happy to put on the gloves with any gentleman who may request it. A fine opportunity is now offered to all who desire it, of seeing this celebrated pugilist while displaying the excellencies of his art.”137 One match, pitting Sullivan against a man called Van Arnam, was set for 8:00 p.m. on June 19, 1850, at the Exchange. Although details are scarce, we do know that Sullivan won the bout.

Sullivan’s story is an interesting one. Born an Irishman in 1813 with the given name James Ambrose, he moved to England during his late teens. While in London, he boxed, robbed and murdered his way into a trip to prison at Botany Bay, Australia. After serving time, Sullivan stowed away on a ship, eventually making his way back to England. Once there, Sullivan got lucky: he fought and beat one of the better boxers in the country. With such prestige in tow, Sullivan made his way to New York City, where his sparring career took flight in earnest. Beating several notables along the way, Sullivan opened his own boxing academy in Brooklyn in 1842. This, however, was far too normal a lot for the Yankee, who soon drifted back into crime by fixing various fights and involving himself in the first sparring fatality in the country. In the aftermath, Sullivan fled west, where he fought in San Francisco and throughout the Mother Lode. He even made his way back to Sacramento to fight again, in both 1854 and 1855, at Holmes’s Saloon on Second Street. His undoing came a few years later when he fixed various local elections taking place in San Francisco. After being found out by a San Francisco Vigilance Committee, he was thrown in jail. Having lived an interesting yet dysfunctional forty-three years, Sullivan was found dead in his cell on April 1, 1856. His demise was likely due to a severe cut on his arm that caused him to bleed to death.

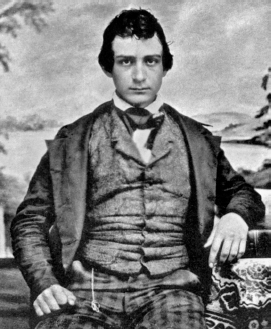

Incorrigible and well-traveled Irishman Yankee Sullivan was one of Sacramento’s earliest boxing attractions and a nationwide political strong arm. Sacramento Public Library.

Although most of the early stage performances at the Exchange were musical in nature, live theater appeared after its 1851 purchase by Doctor Volney Spalding. After his management of the city’s first hospital resulted in an official investigation and consequential removal from his post, Spalding needed something new. The Harvard graduate’s interest in both theater and real estate led him to purchase Lee’s Exchange. This resulted in an overhaul of the venue and an immediate disbanding of the saloon. Despite Spalding’s chief hope to transform the Exchange into a theatrical hub, he soon recognized—and wisely so—the obvious allure of maintaining a saloon. The result was the establishment of the American Saloons, which were located inside the theater. It is not entirely clear how many saloons there were, nor is it known if they operated independently from the theater, but patrons could expect “the choicest liquors and the most fragrant cigars…kept constantly on hand.”138

Finally, it is worth noting the few degrees separating Lee’s Exchange from John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The assassin’s brother, Junius Brutus Jr., was the first manager of the American Theater, and all the Booths, save John, would come to play Sacramento: Junius Jr. in Othello and Richard III, Junius Sr. in the Iron Chest and Edwin in a number of roles. The family held a varying presence in the Sacramento acting scene for years to come, ending with Edwin, like brother Junius years earlier, playing roles in Othello and Richard III in 1887.

The most natural sobriquet for the Gold Rush saloon had to be the El Dorado. The best known of the El Dorado bloodline was brought to life for $26,000, in late October 1850, at the northeast corner of Second and J Streets. Founded by Reuben Raynes and Samuel P. May, the saloon was described in the Transcript as being “simple, chaste and beautiful” with high, white walls and elements that conjured “a simple chasteness and classic finish to the room.” The paper goes on to describe walls “ornamented with a few simple oil paintings, colored engravings and with elegant mirrors.”139 In overall appearance, an eyewitness described the El Dorado as a “large saloon in the great brick building…beat[ing] everything in the city, except one,” that being the Orleans.140

Acting savant and Unionist Edwin Booth spent considerable time in Sacramento, acting at Lee’s Exchange and other spots. Center for Sacramento History.

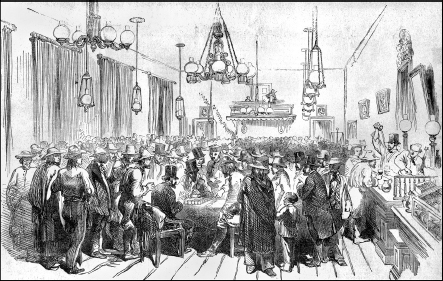

Vouching the described detail is the only existing depiction of the interior of an early Sacramento saloon. It was presented in the June 5, 1852 Illustrated London News and shows the grand height of the El Dorado’s ceilings with a series of ornate chandeliers, an elevated bandstand, tall windows with thick, flowing drapery and wall-to-wall people, most American and Anglo-European, some Mexican and some Asian and African American, but all gambling, gawking and/or drinking—much like our earlier description of the Round Tent. The News correspondent also described the El Dorado as a place

where thousands of dollars change hands daily. There are in this room twelve banks of gambling tables, each having from five to twenty dollars. The games played are monte, faro, roulette and dice bearing the six first letters of the alphabet. Nearly everyone has his Colt’s revolver under his coat, secured by a belt. There are a pianist and violin players, who perform in the orchestra day and evening. Every colour, complexion and country of the universe may be seen grouped together here.141

This 1852 lithograph shows the El Dorado Gambling Saloon and a rare interior view of a Sacramento saloon. Sacramento Public Library.

Years later, in 1893, San Francisco’s Call brought further description to the El Dorado, calling it the “largest and most attractive gambling-house in Sacramento,” boasting a “bar fifty or sixty feet in length extending down one side of it and ten or twelve gambling tables ranged along the opposite side.” The paper further paints the bar as an “elaborate piece of workmanship…furnished with silver and cut glass and against the wall back of it hung mirrors worth a thousand or more dollars each and oil paintings of still greater value.”142 Suspended near the rear of the saloon on a platform were ten to twelve musicians. Two notables were violinist Professor Meyer and pianist George Pettinos, both of whom played together at the El Dorado in 1851. We also know that the upper floors held several private rooms, including spots for large-stake gaming. In the words of the Call, “no one with less than thousands to hazard was admitted to these games, where fifty-dollar slugs, double eagles and golden ounces were the coins usually applied in betting.”143

In regard to El Dorado violence, Lord speaks to an incident, just prior to Christmas 1850, when “five or six men blazed away” at a gambler named Ross. His return volley “passed between three persons who had been standing at the bar and made a deep indention in the counter.”144 As bystanders started to flee, police corralled one of the aggressors and the others escaped. Gold Rush Sacramento’s violent streak and community of saloons necessitated a police presence. One had been in effect since 1849, with the appointment of N.C. Cunningham as city marshal. His original force consisted of two deputies, which expanded to twenty full-time officers in 1852, with ten on duty at any given time. For an agency that was making an average of 145 arrests a month by 1853, patrolling the city must have been harrowing.145 Thanks to the Common Council, salaries for both the chief of police and his deputies were raised considerably in the summer of 1852. However, still lagging in 1854 were police accommodations at the station house. Their substandard condition—perceived to be worse than that of the holding cells—coincided with a rash of officer illnesses “in consequence, it is thought, of the dampness of the brick floors and the excessive ventilation of the rooms.”146 Amid public and press sympathies, this aspect of the department appeared barely tolerable, even for their “unceasing…exertions to ferret out and bring to justice the many thieves in this city.”147

One notable encounter between the police force and rowdies took place at the El Dorado in December 1851.148 While on patrol, an Officer Chandler came upon a disorderly group led by one Charles Turnbull. After locating the rabble-rousers inside the saloon, Chandler and partner Officer Hayward approached with deliberation. But just as the party was told that an arrest was imminent, someone struck Hayward violently across the face with a pistol. When the dust cleared, the perpetrator, a man named Barnes, was apprehended, and the issue appeared to have passed. Further into the evening, however, the ringleader Turnbull was mysteriously shot while retiring to his room. He survived his wounds, but the burning question related to who committed the crime. Was it Chandler, avenging the brutalization of his colleague? Or perhaps it was Hayward, seeking vengeance for the same? Whatever the case, the facts are few, and the story has been lost to the fogs of history.

Just days later, an El Dorado shootout between gamblers Thomas Moore and Alexander McAllister illustrated the various perils awaiting the saloon manager. With there already being bad blood between the two, McAllister entered the saloon at about 10:00 p.m. looking for Moore. When McAllister found Moore, the latter was in conversation in the rear of the saloon with manager Raynes. After Moore exclaimed “Stand off, I want nothing to do with you,” McAllister took his weapon and fired at Moore, but with no effect.149 With Raynes lunging at the shooter, Moore then fired four shots at his foe, all of which connected. The Union described the first shot as “entering the scrotum, pass[ing] through the intestines and out the crest of the ileum.”150 This was the shot that, after thirty-five minutes of what must have been unthinkable pain, left McAllister dead. Raynes sustained a gunshot wound to the hand. Moore was immediately taken into custody by police officer Whittier and then tried in court, where he was found innocent under the judge’s ruling of “justifiable homicide.”

The El Dorado was also a venue for the deft skills of one of the region’s true celebrities, gambling savant Charles Cora. An immigrant from Genoa, Italy, via New Orleans, Cora had the idea of prospecting not through hidden veins of ore, but by way of felt-topped faro tables. His one known El Dorado appearance culminated in an epic shootout with a different Thomas Moore on October 26, 1852. The spat grew “out of some previous dispute at the gaming table.”151 Affairs started inside the El Dorado but soon made their way onto J Street, where several shots were fired. With no injuries recorded, both men were arrested and held on $1,000 bail, but it is likely that the affluent Cora spent little time in jail. Not three days later, Cora was again involved in a shooting, this time at the Challenge Saloon with a John Lenear. Bystander P.S. Schermerhorn, a laborer in his early forties from New York, was hit in the groin by a stray bullet. Cora’s name will surface again later in our discussion.

Italian-born Charles Cora became a legendary gambler but was hanged in infamy in 1856 by the San Francisco Vigilance Committee. California State Library.

On a much lighter note, it was the El Dorado that illustrated how saloon fighting was not the sole province of the customer. In December 1851, two of the saloon’s musicians got into a scrape “as they were mounted up in the orchestra box exposed to full view of the crowds below.” The Union continues to tell us that “the piano artist, although by far the larger man, was rather worsted in the conflict.” In the end, it appears that both parties mended ways and “struck up and performed the next tune with uncommon spirit.”152

As of March 1851, the Humboldt, resting at 28 J Street, was vying strongly with the El Dorado for crowds.153 Perhaps the most colorful—albeit grim—Humboldt description comes from Horace Bell:

Imagine yourself at the Humboldt, away out on J Street—a grand rag palace or gambling hell, literally swarming with gamblers and desperadoes of all classes and nativity, with brazen-faced, gaudily-dressed, painted and powdered harlots, who sat beside the gamblers at the monte banks, faro tables, rouge et noir, lansquenet, roulette, rondo and other games; but I hereby bear witness that these games were played at the Humboldt with a greater degree of fairness, integrity and honor than could have been found in any other country on the face of the earth, because if a man was caught cheating he was killed on the spot.154

On one day at the Humboldt, in September 1850, two different gamblers were nearly killed over gaming disputes. One of them was “dangerously stabbed in the head,” while the other was “horribly disfigured in the face.”155 One month later, the saloon hosted an altercation between two men, Dunn and Russell, over the “ownership of $40.” It resulted in Russell clobbering Dunn with a four-pound weight that cut “through his hat and inflicting a most dangerous wound on the back of his head.”156

A classic Humboldt tale of long odds and born legend was relayed, also by Bell. At one end of the encounter stood twenty-year-old Joseph Stokes, a mild-mannered Sacramento bookkeeper and son of a Philadelphia banker. Typically a modest observer of gambling, Joe became so much more than that one evening at the Humboldt. At the end of the business day and with saloons going into full swing, Joe, like so many young men, wanted to be part of the action. While watching a game of monte, he grew suspicious of Tom Collins, a renowned gambler and, as Bell puts it, “first class fighter.”157 Tensions spiked when Joe accused the dapper gambler of “drawing waxed cards while dealing.” After hearing the accusation—libel of the highest degree in the gambling community—Collins softly counseled Joe to leave the saloon, giving him two minutes to do so. Refusing, Joe calmly dared the gambler to dispatch of him. Collins jumped from his chair and pointed a gun at the bookkeeper’s head. Joe’s reply? “If you are cowardly enough to shoot an unarmed man then blaze away. I don’t belong to the breed that runs.” Immediately, three shots were discharged from Tom’s gun. At a distance of ten feet, one round grazed Joe’s head, a second missed and the third hit his upper arm. When a bystander provided Joe with a loaded revolver, he aimed and fired. Seconds later, the great Tom Collins lay dead on the floor of the Humboldt, with a bullet hole in his neck. It is not entirely clear where the brazen Joe went from there. However, Bell does give the reader the impression that he morphed into a kind of noble terror, roaming the West, intimidated by none and ever dedicated to ensuring a fair fight.

The Humboldt’s run was short. A few months after the Transcript intimated the decline of gambling activity at both the Humboldt and Lee’s Exchange the paper announced the sale of the Humboldt’s furniture and fixtures in May 1851.158 The residential vacuum was soon filled by a new saloon called the Oriental. The saloon debuted in July 1851 under the management of Samuel Colville, an Irishman in his mid-forties. The ambitious Colville came to California in 1849 on the steamer Isthmus and never looked back. He would also draw distinction by becoming the printer of several of Sacramento’s annual city directories.

Early on, the Oriental was “fitted up in the most splendid and costly manner altogether with a view to the comfort of its patrons.” It also boasted a cigar stand, under the capable hands of a “lady”; billiard tables; and four splendid bowling alleys.159 Though such features were nice enough to attract many a patron, a common thread between saloons—both in Sacramento and nationwide—was a desire to lure customers through some great novelty. Any number of factors—auctions, lotteries, art, musical acts, theater and often the unexpected—all served as the veritable “hook.” In the summer of 1851, the Oriental’s “hook” was “a practical exemplification of the famous ‘bloomer’ dress.”160

As the Union correctly states, Bloomerism was “a style of female dress lately adopted in Eastern cities, first introduced by Mrs. Bloomer and daughters.”161 Bloomerism, energetically promoted by one Amelia Bloomer, was a radical shift in women’s fashion that advocated an external dress that was fitted just above the waist and hung down three or four inches below the knee. Fitted under the dress were flowery, frilly pants that fastened just below the ankle.

The trouser-like look elicited praise from those who promoted women’s rights and a desire to live in something other than the traditional confines of the heavy, uncomfortable dress. In fact, suffrage icon Elizabeth Cady Stanton “was delighted with the new style and adopted it at once.”162 This fresh fashion ideal, symbolizing freedom and a shift in the image paradigm, quickly made its way to California, where it would stick, but only briefly. As the impractical dictates of fashion wielded a greater power than the practical comfort of the Bloomer, the style found no permanence in California. Be that as it may, Colville’s Oriental did its part to promote a newness that went far beyond a simple change in fashion and well into the realm of breaking the conventions of tradition. What’s more, in an environment where chances to spy the female form came few and far between, a look at such revolutionary garb must have done the dusty miner’s heart good. That said, like its predecessor, the Oriental didn’t last long. In fact, by July 1852—not more than a year after opening—the Oriental was put up for sale.

Bloomers were more than a fashion alternative; they were a way to get female-starved miners and laborers into Sacramento’s Oriental Saloon. Library of Congress.

A somewhat forgotten pastime of Gold Rush Sacramento was bowling, an ancient game brought to America by Manhattan’s early Dutch settlers.163 Once here, the sport’s popularity grew and, with the coming of the nineteenth century, possessed a particularly strong hold with the immigrant-laden American working class. Accordingly, the construction of bowling alleys in saloons sealed what seemed a natural marriage and created what would be referred to as the “bowling saloon.” The saloon was, in fact, where the sport was originally showcased to the masses, and although not as popular as gambling, it soon surfaced as a legitimate diversion for a large cross section of Americans, including Sacramento’s Gold Rush community. The local Union expressed its excitement for bowling by not believing that there was a more healthful or rational exercise than rolling Ten Pins, while also extolling the erstwhile Oriental for hosting a place “congenial to persons wishing exercise alone.”164

Mentions of Sacramento bowling can be traced back to Heinrich Lienhard’s reference to Peter Slater’s maintenance of an alley at Fort Sutter’s central building. In the context of time, this was well over a year before much at all existed at Sutter’s Embarcadero, let alone at a saloon. It was not until 1849 that the first bowling saloons made their way into Sacramento proper in the form of the Humboldt, the El Dorado Exchange (at Front and J Streets) and, soon thereafter, the Oregon. Even though details are scant, the Humboldt was described as containing lanes that were separated from the rest of the saloon by an oilcloth curtain. And as we know, its replacement, the Oriental, continued to run alleys even to the extent of holding tournaments, with winners receiving prizes in gold. Even less is known about the Oregon, which was described by Lord as running “three bad alleys,”165 while the Cooper lithograph identifies the establishment as the “Oregon Bowling Saloon.”

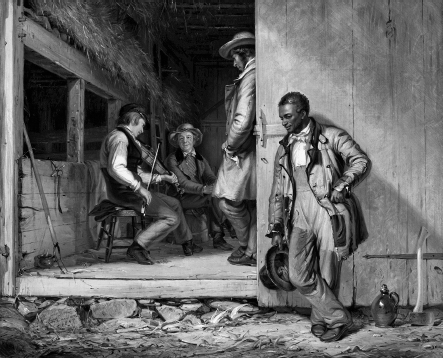

In all fairness, the Oregon, which opened in August 1850, was much more than what its bowling alleys could offer. Under the management of William L. Chrysup, a native of Kentucky, and L. McGowan, the Oregon fit the Sacramento saloon archetype, providing musical entertainment and boasting an elevated orchestral perch “at the upper end of the room.”166 The saloon also hosted a number of minstrel groups, singing “Ethiopian songs, with banjo, violin, tambourine and ‘bones’ accompaniment.”167 Renowned California architect A.P. Petit executed the design and construction of the Oregon, which the Transcript declared a “splendid and new saloon.” The paper went on to call the Oregon “one of the neatest saloons in the city” and commended its taste in art, particularly a copy of William Sidney Mount’s The Power of Music.168 The piece presents a young African American male who, with a smile on his face and standing out of sight outside a saloon door, listens to music being played by a hard-fiddling European American.

In this pre–Civil War era of racial compartmentalization, Mount’s piece was precocious. Individuals may have been oppressed into understanding their proper social place, yet there were indeed ties that bound classes, sexes and races, with music certainly being one of them. Contrasting as much is a story relayed to us by de Rutte. He recalls enjoying a drink in the saloon of the Hotel de France when in walked a man of mixed European and African race. The owners, two French women, served the man and naturally took his money. In seeing this, the whites that were present, many of them politicians, recoiled. As de Rutte states, “At the sight of the [customer] swallowing his drink, the senators and representatives stood up as one man. Refusing in their haughty indignation to accept change for their money from the same hand which had just served a negro, each of them silently placed a dollar on the bar. Then like a herd of frightened deer, the gentlemen disappeared out the door, never to return.”169

Mount’s Power of Music presented a dose of guarded optimism at what music could do for antebellum America’s social climate. Cleveland Museum of Art.

What does this incident say about the racial climate of Sacramento in the early 1850s? Although it says a good deal, there is yet more to the story. It is undeniable that racial tensions, especially those engendered by Gold Rush jealousies, ran high. They were even institutionalized through state law when the 1850 Foreign Miners Tax was enacted to tax non-Americans a percentage of whatever they pulled out of the ground. The tax extracted twenty dollars per month per noncitizen for the “privilege” of working the mines. Although such behavior was patently xenophobic and racist, it is important to note that it was not entirely transferable to the saloon milieu.

From the international mobs at the Round Tent to lithographed visions of a diversified El Dorado clientele, Sacramento’s saloon culture could enjoy, at least on the surface, interludes of general tolerance. What’s more, and with some exceptions, African Americans, Mexicans, mixed-race South Americans and Asians could often use white-owned saloons with some degree of freedom, not to mention the nonwhites who were either employed or even known to possess their own saloons. Overall, a few factors seemed to have made Gold Rush California and saloon culture somewhat more tolerant than other parts of America. One reason may have involved the equalizing element of capitalism. Quite simply, saloons and other businesses wanted patrons. If that meant a moderation of one’s previous views on race, then it seemed to have been done more often than not. One saloon in Marysville, known as the Round Tent, was more than willing to welcome its customers “with no regard to distinction of color.”170 Scottish physician and journalist John David Borthwick also speaks eloquently to this very practical form of democracy by stating that the “almighty dollar exerted a still more powerful influence than in the old states, for it overcame all preexisting false notions of dignity.”171

David Johnson’s “labor theory of value” has ample relevance in this regard.172 Accordingly, skin tone appears to have mattered less in an environment where one’s industry and guile often meant the difference between life and death. Likewise, it may hold true that when one is placed in a region where the most basic elements of humanity are of premium importance (e.g. intellect, industry and guile), superficial traits—color, ethnicity, nationality, accent and religion—quickly become less important. That said, basic geography and the absence of exclusive institutions so common to the “civilized” eastern United States proved just as democratizing as Borthwick’s observations of unbridled capitalism.

Also worth mentioning is California’s status as a free state, meaning that slavery was outlawed in the state by virtue of the landmark Compromise of 1850, albeit at the heavy expense of the Fugitive Slave Act, which mandated the return of escaped slaves to their owners. What this meant for California was elementary: free African Americans could roam the state with at least some peace of mind that skin color had little legal bearing on their lives, a notion that appears to have transferred itself into many of the state’s saloons.

A less influential, yet valid, factor relates to the great number of Europeans who were fleeing 1848’s revolutions, the bulk of which started during the same month (January) that gold was discovered in California. English, Irish, French, German and Italian nationals were all subject to some level of political struggle, making the flight to the new American territory even more palatable with the news of gold. Based on their revolutionary principles, how likely is it that many of them would have belittled themselves to discriminate? Many lived as bourgeois liberals who, armed with education and the experience of life under divine-right monarchy, viewed the quality of a man to be intrinsically tied to his character.

France, the flashpoint of the revolutions, provided in one delivery alone and according to the Union, an influx of “two hundred representatives of ‘la belle France,’ many of whom immediately trudged mountainward with pipe in mouth, pack on back, casting care to the winds and as jolly as Frenchmen can be.”173 Just months earlier, another group of Frenchmen had quickly rushed out of Sacramento’s Gem Saloon in an attempt to avenge the shooting of a countryman whose sole offense was advocating due process in the case of a Chilean man’s possible murder of an American in the foothill town of Jackson. The Gallic presence in Sacramento became so profound that beginning in July 1853, a version of the Democratic State Journal, the Journal Democratique de l’Etat, was printed in French.

As the Gold Rush pressed on and foreigners streamed forth, Sacramento became increasingly quartered, with the greatest concentration of race-centered saloons settling within the city’s westernmost wards. Notably, of the 962 African Americans who lived in California in 1850, most lived in Northern California and many in Sacramento, where they established corridors along both I and Third Streets. It is there that the city’s 1854–55 city directory lists no fewer than twelve African American–owned business, including Albert Grubb’s Delmonico Saloon (L Street between Third and Fourth), Edward Hill and William Smith’s St. Charles Saloon (Third Street between J and K) and Charles Taylor’s Indian Chief Saloon (Third and I Streets). Overall, by 1860, Sacramento’s African American population would come to make up 2.9 percent of the city’s 13,785 residents.

I Street’s Tennessee Exchange was a particularly popular refuge for African Americans. Although names and the exact location of the Exchange are unclear, clear enough is the area’s violent side. One incident, between two African Americans, turned for the worse when the keeper of a gaming table, Augustus Ennen, was shot by an unnamed aggressor, all within the context of a “fascinating game of poker.”174 The dispute arose over the rightful ownership of a certain piece of property that was at stake in the game. The unidentified figure then took the money lying about the table and left. When challenged by Ennen, the stranger fired two shots, hitting the dealer in the stomach and wrist. For Ennen, the wounds were serious but not life threatening. The shooter escaped on horseback and avoided arrest.

The Gem, also on I Street and not to be confused with its J Street counterpart, represented the rougher-style saloon, much in the mold of the earlier Mansion House. One of its more notorious rows took place between African American William Green and Mexican Francisco Navares.175 It was Independence Day 1852, and the hostilities rose from a game of monte. Navares, who was highly intoxicated, challenged Green, who in response pulled his revolver and fired three times. When all was done, Navares was mortally wounded and Green in custody of the police. After “intense suffering,” the Mexican finally died on the following day. “By some quirk of the law,” or so said the Democratic Journal, Green escaped hanging. Green’s penchant for violence was again seen at the Gem in October 1853.176 Over a game of cards, Green and a man referred to as “Negro Jim” pulled guns at one another, firing several shots in between. In the exchange, Green was hit, falling to the ground. After getting to his feet, Green fled but was eventually caught, as was the man who shot him.

Not all was so gruesome at the I Street saloons. The Democratic Journal relates the much more lighthearted story of a drunken African American fellow who, on an evening in early December 1853, just in front of the Tennessee Exchange, possessed “a bible in one hand and a psalm book in the other” and “imagined preaching to a Negro camp meeting.” The sermon, however, turned out to be an abbreviated one because of “a weakness about the knees, precluding the possibility of standing erect without the aid of a pulpit to support himself upon.”177

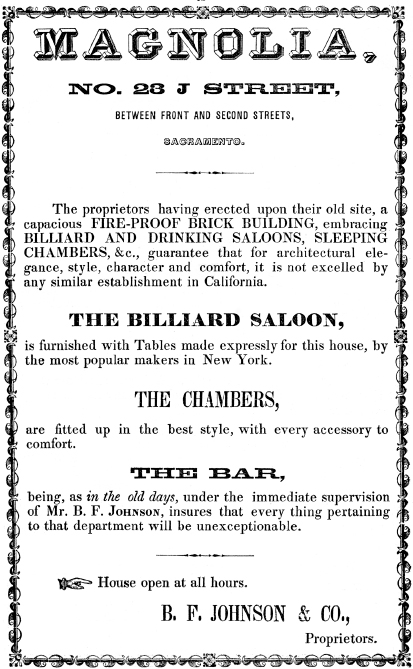

Not surprisingly, many nineteenth-century saloons were politicized. One such spot was the Magnolia, which, having opened in the spring of 1851 at 123 J Street, was described by the Union as “by far the most handsome and pleasing saloon in the city. There is no glaring splendor exhibited in its decorations, but a sober beauty pervades its appearance, as sober deportment characterizes its patrons. The floors are covered with the finest carpeting, the seats and sofas of high finish invite a lounge or a quiet rest. With the Woodcock on one hand and the Magnolia on the other, we can have no reasonable excuse for starving or thirsting.”178

The Magnolia and Union appear to have enjoyed an amicable existence, despite the fact that the paper was operated by those partial to the Whig Party and the Magnolia’s Kentucky-born owner, Benjamin Franklin “Baldy” Johnson, was a Democrat, a party referred to by the Whigs, most pejoratively, as “Locofocos.”Johnson, however, was not the typical Locofoco in the eyes of area Whigs. In addition to his proprietorship, he was a city alderman and therefore influential. Looking as if both parties were intent on cultivating ties between one another, one passage in the June 1851 Union states that although a Democrat of the “darkest dye, [Johnson] is a most gentlemanly and polite host and of our citizens desirous of imbibing a cold cobbler or hot punch, will be certain of obtaining an excellent decoction at this Saloon.”179 The passage provides at least some view of the depth of interparty patronage at this time in Sacramento. Another newspaper entry—and harbinger of Sacramento’s burgeoning political heritage—spoke to the ideological hothouse that Johnson’s Magnolia had become by claiming “under its roof more politicians have been made and unmade than in any other five buildings in the state.”180

The quid pro quo between Johnson and the Union seems to have ended in December 1851 with the saloon’s sale to “Arnold & Barker.” According to the same publication, Johnson and a co-owner decided to leave “for their former homes.”181 As an interesting aside, Johnson was known, during 1849 and the early months of 1850, to have kept the Magnolia’s refreshments cool by refrigerating them in snow obtained from the nearby mountains. As stated in Thompson and West’s history of Sacramento County, the “commodity”—acquired for thirty cents a pound—had to be “packed on mules a considerable distance before reaching the wagon road” and then into Sacramento.182 The topic of refrigeration will be discussed further in later pages.

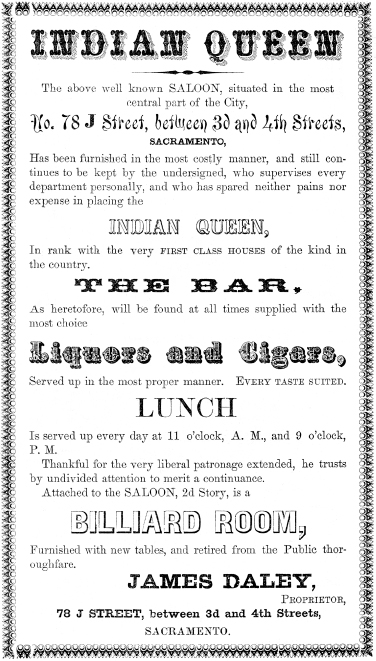

Across the city, business-to-business patronage between saloon and newspaper spanned the political spectrum. As evidenced by a few passages in the Union, the staunchly Democratic Indian Queen on J Street, between Third and Fourth Streets, in spite of being a place of several partisan meetings, also had a tight relationship with the “enemy” newspaper. The saloon, operated by the tandem of the Daly brothers, James and Bernard of New York, and Jacob Remmel, supplied the Union with generous amounts of eggnog, thus earning mention in the paper. The Indian Queen was also fondly cited for its kindness in the Union’s competitor paper, the State Democratic Journal. The saloon’s name, a clear reference to Algonquian maiden Pocahontas, was blended into this passage from January 1853: “Messrs. Daly and Remmel…know how to honor the name of the aboriginal princess by making the best of milk punches and dealing them out by the gallon, as the Union office can testify from a trial they had of its qualities on New Year’s Eve.”183

Kentuckian B.F. Johnson’s Magnolia represented the most political (in this case, Democratic) that a saloon could be. Sacramento Public Library.

The platforms of Whig and Democratic Parties, the two most influential in this period of American history, were simple. The Whigs, a nineteenth-century spinoff of the National Republicans, favored the supremacy of Congress over the presidency and sought a program of modernization and economic development. The balance of their support came from the professional classes: bankers, storekeepers, factory owners and commercial farmers. On the other hand, Democrats, seasoned through the populist views of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, favored a supreme executive branch. They also envisioned America to be a land where agricultural-based values were best suited for the development of a democracy. In their eyes, modernization would only create an elite class that would subvert democratic values. Immigrant groups, particularly Irish Catholics and Germans, plus those living in the nation’s agrarian regions and the developing western states, typically voted Democrat.

By August 1853, the Whigs had established a “headquarters” of their own. Whig partisan Vincent Taylor seems to have been the catalyst for the spot that was located on Second Street. Known as the Whig Headquarters, it boasted a “large hall on the second story and a bar of the choicest spiritual manifestations, from which to derive strength and courage during the hot weather and strife of a political campaign.”184 One of the saloon’s more notorious claims to fame and definite “hook” was its exhibition of the supposed head of Joaquin Murrieta—an area folk hero to some, but a scourge to others—and the hand of comrade “Three-Fingered Jack,” a nickname for Manual Garcia. Both body parts were preserved in jars of alcohol. The Union provided particularly gruesome detail on the state of the head: “A protrusion of jet black hair falls below its ears, while the sightless orbs indicate them to have possessed at one time of a flashing luster, such as is common to a majority of the Spanish race and eminently so to that portion of it with craft, cunning or superior intellectual attainments.”185

The Daly brothers’ Indian Queen grew to have multiple locations throughout the city, the first Sacramento saloon to do so. Sacramento Public Library.

Another prime Whig watering hole was Radford’s, operated by the interesting character of Captain John Radford. Located in the basement of Langley’s Brick Building at 19 and 21 J Street, the saloon was described in December 1851 as “not quite completed,” but “the furniture is costly and in excellent taste, while the spacious room will accommodate the patrons of the establishment.”186 The Union goes on to tell us that “the liquors, as well as everything else, were bought by Capt. Radford himself, which ensures them to be of unsurpassed quality.”187 The spot also endeavored to provide newspapers from all parts of the country, an effort not uncommon at many of the city’s saloons.

Radford also seems to have had a reputation as an exceptional storyteller, not a bad draw for a new saloon. He spoke of the “excitements of a deer or antelope chase, the dangers of the bear fight, or the still more thrilling incidents of an Indian fight.”188 Radford was a devout Whig, therefore willing to host a number of party events, including a convention for the selection of candidates for the city’s First Ward in the spring of 1852. The saloon also made an effort to provide oysters as part of its complement of wares. Their availability, increasingly common at this time, must have been a warming comfort to those from New England. Radford obtained his oysters from Oregon, and it was anticipated that in a year, his saloon could offer “an abundance of oysters of the largest size and quite equal to those enjoyed by our more favored Atlantic friends.”189 They were also said to have compared favorably to oysters from the Chesapeake Bay region of the Middle Atlantic States.

Not to be lost in the many functions of the Gold Rush saloon is the element of prostitution. One of Sacramento’s best-known spots for prostitution was the Palace. Located on Second Street between I and J and in existence at least as far back as November 1850, the Palace possessed several of the traits defining the typical Sacramento saloon: it served alcohol, hosted gambling and provided the occasional room for let. With prostitution legal at this time, the Palace and other spots preyed on the needs of scores of 49ers. To gauge the demand for paid companionship, one need only look in local papers to find advertisements for “Gonorrhea Mixture” and “Red Drop,” which were sure to cure syphilis “without mercury or any poison.”190 The Palace’s proprietor and madam, Fanny Seymour (also known as Fanny Smith or Fanny Sweet), is clearly one of the more fascinating figures in this period of Sacramento history. The Union, in addition to commenting on “her Grecian beauty,” described the young Louisiana native as

tall and graceful in her person, but deficient in the feminine delicacy usually characterizing that order of women, with a keen perception, quick motion and dignified carriage. Her complexion is fair, with ruddy glow of perfect health; her eye is of light gray, strongly marked and expressing in an eminent degree the possession of strong passions and implacable animosities.

…in the earlier years of the State, her belt was garnished with a revolver and bowie knife, whose threatening aspect was believed to be of no idle or mere braggadocio import; and the result has proven that she knew how to use, as well as display such weapons.191

Fanny was also an irrepressible gambler. She loved faro and was known to drink and gamble her way into wagering hundreds of dollars at a time. Nonetheless, she was stoutly independent, owned her own business and, according to the Union, possessed a personal value of at least $50,000.192

The defining moment in Fanny’s Sacramento tenure came in December 1852. It was a Monday evening at the Palace, and Albert Putnam, a stage driver, sought the affection of a woman. Reports indicate that Fanny had been drinking and was likely intoxicated when she insisted that Putnam purchase a bottle of wine, a customary and mandatory act for someone sitting in the Palace’s “wine chair,” as Putnam was. The concept of the chair, common in many a brothel, was based on a trade: to sit in the most comfortable chair in the brothel meant payment in the purchase of wine. Putnam, while sitting in the chair, refused to do so. Not leaving things at that, he told Fanny to, in essence, sober up, “uttering a threat if she did not.”193 Given her defiant disposition, Fanny’s response was perhaps predictable. She left the room, grabbed a Colt revolver, returned and shot Putnam in the back.

After the shot and realizing the gravity of her act, Fanny ran onto Second Street and found a police officer. Soon after reporting her deed, she was taken into custody and held at the city’s station house. Unlike the Roe incident two years prior, the marshal was ready for any mob vigilance, placing Fanny within the safer confines of a boat—likely the prison brig La Grange—until the crowd’s ire subsided. While the resolution of the Fanny saga appeared elementary, a twist developed. Much of her fate would hinge on the presiding judge’s decision to offer bail. It is not clear why such was tendered in the event of what appeared a clear case of murder. Perhaps it was Fanny’s gender, her status as a respected businesswoman or the fact that she was the mother of several children. Whatever the case, she was released on bail in early January 1853. Notably, those who bankrolled her release were the familiar names of Reuben Raynes of the El Dorado and D.V.M. Henarie of the Orleans. Patronage, again, seemed to play its part in city and social affairs. How likely is it that the relationship between all three figures, one based on business and mutual benefit, was a factor in prompting her release? Or perhaps it was Henarie and Raynes’s modest desire to see a friend removed from jail? Regardless, she was out, never again returning to Sacramento.

Perhaps the most entertaining saloon moniker at this time was the Bull’s Head, owned and operated by Captain Edward “E.J.” Feeney. The name’s origin likely relates to the bovine skull that sat either just outside or inside the saloon. Setting it apart from other establishments we’ve discussed, the Bull’s Head was not on J Street, but rather Fifth and K. In addition to its operation as a saloon, it served as a polling place, eatery and boardinghouse, with single meals costing fifty cents and a week’s lodging ten dollars. The saloon boasted a barroom, dining room, bake oven, stoves, its own horse stable, several rooms (either for office or residential use), a rear balcony and, according to the Union, an artesian well, “the only one in Sacramento city, which contains an exhaustless supply of water and is convenient and indispensable in the case of fire.”194

The Bull’s Head was also one of the first Sacramento saloons to have offered the “free and easy,” an attempt by smaller businesses to employ a scaled-back version of the “concert saloon.” The Transcript quipped at the nature of the event, stating, “What’s a ‘Free and Easy?’ Now we do not know what the performance is, but the name is certainly ominous.”195 Anything but ominous, the “free and easy” was typically cheap and quick and involved a magician, comedian/actor or crooner—anyone who could add value to the saloon experience.

The tavern’s proximity to the Horse Market, located at the intersection of Sixth and K Streets, made it a prime meeting place for both teamsters and stockmen. The Market was the place for the purchase of four-legged transportation, boasting a large selection of saddles, harnesses and carriages. It also served as a place where miners, as they ascended the foothills, grabbed supplies. The area’s distinguishing landmark was a massive oak tree, providing an oasis during the area’s hot summers as well as ample coverage from winter and fall showers. It is also likely that this is the same tree that Frederick Roe was hanged from. The Transcript’s March 20, 1851 description of the spot is as follows: “For a good portion of the day, this is decidedly the liveliest portion of our city. Day after day the auctioneer’s hammer descends at the last bid of some ‘lucky hombre,’ yet the business does not flag. We expect this trade to continue a permanent and relative one, as long as the wants, whims and habits of Californians are what they are.”196

Not short on bodies or on spots for congregation, the Market also saw its fair share of political rallies and, of course, a steady stream of gambling. Both French monte and shell gaming were common at the Market. The best description of the Market as a gaming hotbed comes from the March 15, 1851 Union: “Let’s not leave the market without another passing glance at a few of its different phrases…‘the tray, the tray! I’ll bet six ounces on the tray,’ comes shrieking from ‘a chap’ about 12 to 15 years old and small of his age…‘who takes the bet?’…‘will you take the bet sir?’”197

As a result of its proximity to the Horse Market, the Bull’s Head was able to enjoy a profitable run. However, it also grew a reputation for being a spot of common misfortune. The first bizarre event took place in April 1850. As several workmen were in the process of blasting a sycamore tree on the corner of Third and K Streets, Bull’s Head barkeeper, Gilbert C. Briggs, stepped out of the saloon to take in both the spring day and distant pyrotechnics. When the explosives cracked, a large piece of timber flew toward the saloon, striking the “door post where Mr. Briggs was standing.” The impact sent shards of wood at Briggs’s forehead and “over the left eye, crush[ing] and mangl[ing] that part of the head in a shocking manner.” Tragically, the trauma left the New York City native dead and his “young and beautiful wife” an early widow, all the result of a simple curiosity.198

Some months later, the odd case of an unnamed customer occurred within the Bull’s Head. Details are few, but one Saturday evening, “a man, apparently in good health, laid down upon a seat” at the saloon. Not long after, it was discovered that he had died. It was never determined what directly killed the man, but a later medical examination “ascertained that the deceased was diseased in several vital parts so seriously as to make it appear strange that he had lived so long.”199 Capping the saloon’s run of misfortune was the sudden, accidental death of owner E.J. Feeney in 1854.200 He was a mere thirty-eight years old.

Albeit overshadowed by their bent for vice, several of Sacramento’s Gold Rush saloons could also cook. One spot deserving mention is the Woodcock, located on 15 J Street. Its original managers were a Mr. Reed and Edwin Cushing, the latter in his mid-twenties from New Jersey. By all accounts, the saloon established a reputation as a top restaurant, especially if one sought turtle soup. The Woodcock also claimed to have on hand “every variety of fish, flesh and fowl which the country affords.”201

The Woodcock’s layout seems to have been quite like many saloons of the time, containing a bar section and “dining saloon,” both of which, according to the Union, were “in point of comfort and elegance, unsurpassed by anything of the kind that we have seen in the country.”202 As a thriving business, and operating with so many desirable commodities about (i.e. money, gold and liquor), the Woodcock, and spots like it, were ripe for break-ins. The Woodcock was violated in June 1851 when the lock on the front door was pried open, resulting in the pilfering of “nearly all the silver spoons in the house, a number of table spoons, boxes of preserved meats, jars of preserved fruits and bottles of champagne.”203