Chapter 4

THE TIPSY PHOENIX: 1853–56

As 1852 ended, 70 percent of Sacramento had been razed by fire. In the aftermath, the city responded impressively: within thirty days, citizens had mustered the construction of 761 buildings. Not surprisingly, 65 of them were brick.213 In fact, by 1855, workers had laid an amazing twelve million bricks. So prodigious had Sacramento’s brick industry become that when it was time for the U.S. Army to start building coastal defenses on Alcatraz Island in 1857, it was the River City that provided the brick.214

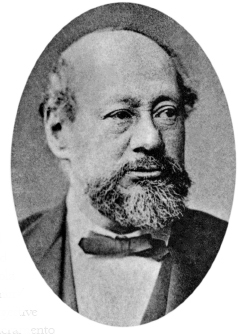

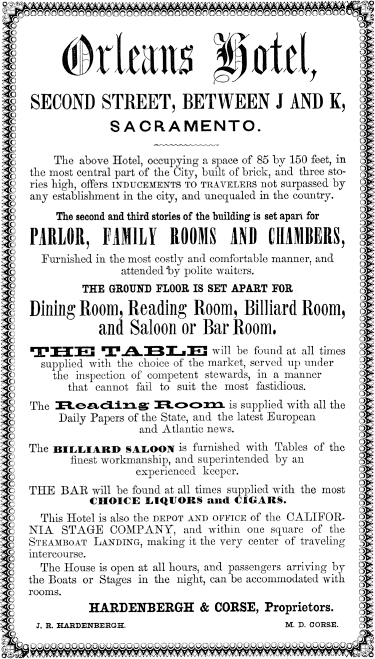

Most aggressive in rehabilitating itself was the Orleans House, but not under the guidance of its original troika of managers. Joseph Curtis, the last of the three to maintain interest in the structure, sold out to Misters David V.M. Henarie and Moore in late January 1852. Doing its predecessors proud, by mid-November, the duo resolved to rehabilitate the Orleans in its original spot, but “entirely of brick.”215 By mid-December, the Orleans stood four stories high, and on New Year’s Day 1853, the saloon portion of the building was ready to open its doors.

The Orleans was the first of the pre-fire family of saloons to open, and it did so at a time when the embattled city needed it most. If the fire weren’t staggering enough, New Year rains flooded the city. The California Alta’s read of the weather was that “the complete penetration of businesses of every kind can hardly be realized by you. The streets combined with the rain drive everyone in-doors. By 3 PM yesterday not a team or dray could be seen on J Street or the levee—a thing never known before in the history of this place.”216

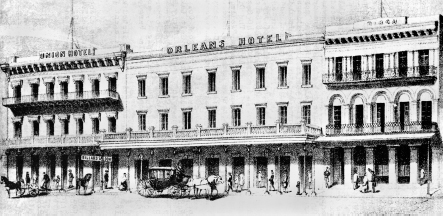

In fact, for many, attending opening night at the Orleans House meant that one had to either go by boat or swim. Regardless, whether entering the saloon that night with soaked britches or dry ones, the experience must have been a grand one. The Orleans’s architect, Charles H. Shaw, spared little. The saloon alone measured some eighty-six by fifty feet, while ceilings reached sixteen feet high. Its cornices were “finished in mastic and stucco of virgin whiteness and its walls adorned with scenic paper of the most gorgeous coloring.”217 A special attraction of the saloon was its illumination by “Enson’s [sic] patent oil gas,” invented and patented by Mr. Thomas Ensor of New York City.218 A total of five chandeliers, each with special burners, would provide artificial light in the saloon, while the entire hotel contained sixty.219 The bar also contained four huge mirrors, each covering a dimension of twenty-four feet high by three feet wide. On its exterior, the Second Street façade of the hotel was built to awe. Not only did the Orleans’s front walk boast three gas-powered lampposts, but patrons were also met by the grandeur of seven glass doors. With the last nail driven, the Orleans had cost $176,000, but for what the Union tabbed the “most elegant saloon in the State.”220

So prestigious had the phoenix-like Orleans become that it was able to draw some of the finest entertainment in the West. In March, crowds again braved inclement weather to see violinist and P.T. Barnum darling Miska Hauser. The Austrian-born virtuoso played to a packed house that included a Union reporter who wrote that sounds from Hauser’s “faultless bow were distinctly heard, like angel whispers, in every part of the room.”221 Days earlier, the New Orleans Serenaders were greeted with “unbound applause” as they treated viewers to “a pleasing variety of negro melodies, wit and stupidity—combined with dances, conundrums, [and] instrumental solos.”222

The post-fire Orleans was both a palace and cultural hub for the early city. Its saloon was also the site of premier entertainment. Center for Sacramento History.

Austrian violin virtuoso Miska Hauser saw the best that Lola Montez had to offer. Look and Learn, Limited.

The post-fire Orleans also served as host to one of the more beloved performers of the Gold Rush era, Lola Montez. The Irish-born actor/crooner/dancer was known for her suggestive “Spider Dance,” which, while in Sacramento in July 1853, was performed in tandem with the “Ole Dance.” The latter movement, according to the Union, “happened to excite the merriment of one or two persons sitting in front of the stage.” However, taking the behavior—or what Montez coined “stupid laughter” coming “from a few silly puppies”—as a sign of disrespect, she refused to continue, exclaiming, “If my dancing does not please the audience, I will retire from the stage.”223 She did just that, agreeing to finish only after a brief performance on violin by Hauser. Far from traumatized by the event, the next day, the waif-like Lola “skipped up” to the violinist, exclaiming, “Dear Hauser, last evening was worth more to me than $1,000. I was delightfully amused and I have added another to the list of my adventures.’”224

By this time, we see the entry of James Hardenbergh, whose co-management of the Orleans qualified him for the city’s small fraternity of saloon-running, Democratic politicians, along with B.F. Johnson of the Magnolia, James Daly of the Indian Queen and Reuben Raynes of the El Dorado (Raynes sought the office of alderman in April 1853). Like the Magnolia, the Orleans proved a spot of true politicking. For politicians of all ideologies, the saloon was a prime watering hole. In spite of “its admirable ventilation, [it could not] cool the heated brow or resolve the momentous questions, ‘Will I be nominated and if nominated, elected?’”225 It was also a venue where political sentiment could easily morph into political violence. Under the headline “Soiree Pugilistique,” the April 13, 1852 Union described a row in which “legislators, ex-legislators and lobby legislators participated.” The entry continues, “The optic of one of the parties was wreathed in mourning,” with “no other damage done.”226 And like its pre-fire ancestor, the saloon was known to host nomination ratification meetings, including one for the Whigs in April 1853, when the bar “was filled to its full capacity.”227

An indicator of Sacramento’s large Yankee presence and, again, the saloon’s culinary flexibility, came when the Orleans hosted a Christmas 1853 “New England Dinner.”228 Held in the saloon, the dinner consisted of a mouthwatering array of items familiar to the Northeastern palate, including oyster soup, salmon chowder, boiled salmon, barbecued perch, clam chowder and lobster salad. This is a far cry from other holiday fare to be served at much less sophisticated establishments, one being Richard Lockett’s Nonpariel Saloon on 68 K Street. On New Year’s Eve 1854, the saloon served a beaver lunch, the meal’s benefactor—“the largest beaver of the season”—weighing forty-seven and a half pounds.229

Lola Montez played nearly the entire American West but would never forget her time at the Orleans Hotel. Center for Sacramento History.

A notable change for the Orleans came in the summer of 1853 with the erection of a new wing, measuring some eighty-five by thirty feet. The addition—made entirely of brick and affixed to the north side of the building—was designed to host the hotel’s billiard tables, which had been located in the increasingly cramped saloon. It was also in this new section that a “gentleman’s private dining” area and “ladies’ ordinary, with private entrance” would be included.230 Concurrently, George B. Bidleman replaced Hardenbergh and Henarie as the Orleans’s manager. The Count, as Bidleman preferred to be called, christened his newfound control of the Orleans with a hearty celebratory meal of turtle soup. The 150-pound tortoise was transported from Mazatlan and transformed into soup that Bidleman and a bevy of friends took “no small portion of.”231

By mid-decade, most of the city’s saloons possessed at least one billiards table. Like boxing, the game’s primary exporter was England. Although the cost of a table and accoutrements made it primarily an aristocratic pastime in the first half of the century, the industrial revolution and consequentially lower production costs brought billiards to the American masses. Once introduced, the game’s popularity quickly blossomed. The earliest record of billiard play can be established as far back as October 1849 at the aptly named Billiards Saloon, located on K Street between First and Second Streets. Its first advertisement in the Placer Times guaranteed an environment “where an hour can be disposed of very agreeably.”232 One of the more intriguing billiard locations was inside the city’s Forest Theater. Opening in fall 1855, the theater offered a chance to enjoy a quick game of carom, sip a drink served up by proprietor Moses Flanegan, and then sit for a dramatization of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Sacramento’s earliest saloons imported their billiards tables from the east. However, as the city grew, so too did outlets for local production. A.H. Bening’s Sacramento Billiard Factory opened in 1855 with a location on K Street, between Fourth and Fifth Streets. In an effort to dissuade prospective buyers from opting for an imported table, Bening emphasized the value of a table made of local wood, stating that “the dry climate of this country seasons the wood better than any place in the world.”233 By 1858, Sacramento had three billiard-table manufacturers, collectively turning out seventy-five tables per annum, each at an average cost of $600 to $700.

With the Orleans’s new roominess, management decided to install a fountain in July 1854. Placed in the center of the barroom, it measured ten feet in diameter. The water was passed through a pipe and forced five to six feet into the air. The hope was that it would add “very much to the comfort of all who may be in the room, by cooling the atmosphere therein.”234 Who knew that Bidleman would soon opt to stock the fountain with fish for the very purpose of angling? In July 1856, the fountain became home to another animal, a pelican that had been gifted to the Count. After promising “to take excellent care of the bird,” he deposited it in the fountain, only to find that it had disappeared after being visited by the Count’s many friends. When asked about the absence of the “aquatic pet,” the Count replied “d—n pelican! He eats twenty pounds of fish a day, and fish cost twelve and a half cents a pound!”235

The sophisticated Orleans Hotel, like so many saloons at the time, was a political hothouse. Sacramento Public Library.

Come September, it was time to renovate the hotel’s saloon, addressing what the Democratic Journal referred to as an “unwieldy and we may say uncomfortable space.”236 Also added was a veranda that covered the entire length of the building, a new coat of paint and expanded accommodations to meet the needs of three hundred residents. Management also saw fit to upgrade the quality of the billiards section of the hotel, spending $7,000 to do so. Such changes were required to accommodate, as we know, the urbane tastes of the city’s burgeoning community of politicians who were so often to “swarm” the Orleans, “the great depot for present and prospective office holders.”237

Not to be outdone by the Orleans, the El Dorado’s co-owner, Reuben Raynes, also set to rebuilding, this time on the northeast corner of Second and J Streets. Raynes’s immediate goal was the construction of a one-story structure that, by the fall of the same year, would be expanded by two more levels. In the interim, however, Raynes, armed with “plenty of nerve and money,” didn’t miss a beat as he set up a faro game operation under a tent near the old location. Just days after opening, Raynes, while occupying the tent’s lookout chair, was approached by an eager gambler who asked about a betting limit. Excited by the question, Raynes replied, “The limit in gold, whether in blue chips or $50 slugs piled straight up, is the top of the tent, and if you say so I’ll have it pulled up five or six feet for your special accommodation.”238

By March 1853, a fully reconstructed El Dorado was back to its irritable self as visitors were stabbing each other with penknives; by April, the saloon was also back to its customary air of ballistic violence, with one such bout taking place between two gamblers, a Mr. Taylor and Washington Montgomery, the latter a Kentuckian employed at the Diana.239 When Taylor contended that Montgomery owed him $10, the latter struck the former in the mouth. At this, the bloodied Taylor left the saloon to grab a pistol. He returned to the saloon with not only a firearm but also his wife. Standing at the ready with his pistol cocked for firing, Montgomery was grabbed by Taylor’s wife. In the ensuing struggle, Montgomery’s gun went off, hitting Taylor in the hand and his wife in the thigh. Neither wound proved serious, but both men were eventually arrested. Then, in the summer of 1853, a roulette dealer at the saloon, identified by the Union as “Dan-Something-or-other,” robbed his employer of $900, escaping on a “2 o’clock boat.”240 Raynes sent an officer after him on the steamboat Orient, but it is likely that the perpetrator was able to catch an Atlantic-bound steamer, thereby avoiding apprehension. Not long after Dan’s exit, Mr. Peters, a faro table operator at the saloon, was robbed when he literally fell asleep on the job. When he awoke, $975 was gone. The Union went on to report that “three Spanish boys and a woman…[were] arrested on suspicion of abstracting the money.”241

At this time, we also see the resurrection of the Magnolia, under the guidance of none other than the returning B.F. Johnson, who, according to the Democratic Journal, “sold out, visited his old home and returned to the land of his adoption with a rose fit to be transplanted in our lovely valley.”242 Why he returned is not known, but in doing so, Johnson accomplished a magical rehabilitation of the Magnolia, as it opened for business by November 11, 1852, roughly one week after the fire. Although a simple frame building in the early going, it proved more than functional for the saloon until a more permanent structure was built. The last night in the makeshift Magnolia was celebrated on August 7, both by Johnson and his new partner, Volney Spalding of American Theater fame. Just days before the adieu, John Sutter’s personal army, the Sutter Rifles, came by the Magnolia for an hour of “conviviality.”243 The Rifles, which eventually became California’s Company A, 184th Infantry Regiment of the National Guard, were formed in June 1852.

Made entirely of brick, the new Magnolia rested at 23 J Street, between Front and Second Streets and just next door to the offices of the Union at 21 J. Built to the tune of $20,000, the saloon’s final dimensions were twenty-two feet in the front, with a depth of ninety-three feet. A second floor, in addition to boasting “a splendid parlor,” contained fifteen “finely furnished rooms.”244 Its façade was of “gray mastic, penciled in imitation of marble blocks and surmounted by heavy cornices with a square finish.” The saloon also contained billiard tables crafted in New York, sleeping accommodations and an “architectural elegance, style, character and comfort…not excelled by any similar establishment in California,” claimed an advertisement in the 1853–54 City Directory. The Magnolia opened on the evening of September 20, 1853, to considerable fanfare, during which “the popping of champagne corks was heard like the regular discharge of musketry from miniature guns.”245 It was the Democratic Journal’s contention that the Magnolia, at least at this point in time, was the “oldest one of its kind in this city.”246

Also part of the post-fire generation of saloons was the Indian Queen. Made of brick and located at 88 J Street between Third and Fourth Streets, it was built at the modest price of $6,000, was two stories high and occupied an area twenty-six feet wide and fifty feet in depth. One particularly colorful passage out of the Democratic Journal describes the saloon’s reopening after a spring renovation:

A crowd of friends availed themselves yesterday of Professor Daly’s invitation to partake of a sumptuous lunch and drinks in honor of the “Indian Queen’s” donning her summer dress. A chaste and beauty-dress [sic] it is and reflects great credit on the designer. We called on the proprietor for a mint julep and as we slowly imbibed the delicious compound…it was luscious; the taste remains with us still. If those who partook of mine host’s hospitality yesterday continue to call for “daily” drinks at the “Indian Queen,” we shall consider it nothing more than he deserves.247

The Indian Queen’s summertime resurrection also coincided with Daly making permanent his relationship with Miss Mary Davies by marrying her at the city’s sole Catholic church, Saint Rose of Lima, in April 1854.

The person of Daly warrants recognition. He was, in a word, dynamic, for while running his Indian Queen, Daly was one of the city’s only saloon-owning firemen, served as an alderman for the city’s Second Ward in 1854 and was also the first of Sacramento’s saloon proprietors to launch branch locations. In addition to the Indian Queen’s first annex at Seventh and I Streets (opening in March 1854) and where one could be sure to find “daily manipulations of a spirited character,” Daly had, concurrently to the branch’s debut, opened the Merchant’s Exchange Saloon, located in the “What Cheer” building on Front Street, between J and K. He claims to have done so in the Democratic Journal “in response to a general demand…for the accommodation of the businessmen on Front Street.”248

While it was Daly’s desire to draw mostly business-class interest, the Exchange and its embarcadero location attracted all types. As the weather improved in late spring 1854, young men, out of work or simply not interested in labor, would race one another on Front Street between K and L for a liquor prize. One particular race, referred to as a “scrub,” pitted ten or so men against one another, devil take the hindmost.249 The sole loser had to pay for the “winners’” drinks, with winnings dispensed at Daly’s Merchant’s Exchange.

Not letting a good thing languish, Daly rehabilitated the “main branch” of the Indian Queen in September 1854. Descriptions of the opening are quite detailed, including the following from the Democratic Journal:

It is most beautifully furnished, being decorated with some sixteen oil paintings. [Daly] has not spared money or time in furnishing his saloon, one single article having cost the round sum of $974. We refer to the magnificent gilt framed mirror. We believe that this is the finest mirror in California.

He regaled his friends on that evening with everything in the way of beverages…in addition to which there was spread a large table…Jim Daly is a most capital fellow; popular and gentlemanly and his friends are “multitude.” Success to the new “Indian Queen.”250

The Indian Queen’s facelift came at a time when Daly’s political sentiments were drifting from Democrat to Know-Nothing. The Know-Nothings, also referred to as the American Party, were a short-lived, nativist-style movement (1854–56) that, in response to a perceived growth of corruption in urban government, tried to blunt the political influence of Irish Catholic immigrants in major cities. The Know-Nothings, largely composed of middle-class Protestants, were also suspicious of the Vatican, feeling that it was the pope’s desire to establish a political network of loyal Catholics throughout the United States and thereby influence public policy. Daly’s declaration for the Know-Nothings, as well as his desire to see like-minded politicos at the Indian Queen, was made in few uncertain terms in November 1854: “KNOW NOTHINGS AND FREEDOM’S PHALANX ATTEND!”251

One of the most influential post-fire upstarts was the Fashion, a place whose prospects matched the panache of its name. Established sometime in November 1852, the Fashion sat at 39 J Street. Its Irish-born owner, John C. Keenan, was described by the Union as that “incomparable leader of the mode…[Keenan]…whose taste for the outer and inner adornment of man is acknowledged to be the sine qua non of excellence.”252 One intriguing aspect of Keenan’s pre-Sacramento life involved his role with the fabled Texas Rangers, a fighting force born out of early efforts to protect Texans from Indian attacks and incursions by Mexico.253 The bulk of the Rangers’ reputation, however, was earned with their performance in the Mexican War of 1846–48, under the leadership of the legendary Captain John Coffee “Jack” Hays. Ireland may have been Keenan’s birthplace, but he appears to have made a home in Texas, where he arrived in the spring of 1849 via Mexico. After doing so, he became a Ranger. Specifics are scant on Keenan’s part in the group, but we do know that he served under Hays after the war with Mexico had ended and prior to departing for California.

After the November fire, the energetic Keenan sensed opportunity and raced to the now-extinct city of Vernon, located at the confluence of the Sacramento and Feather Rivers. Once there, he purchased a prefabricated wooden structure and floated it to Sacramento.254 The new saloon then bowed out of the city’s cultural scene for a six-month period, returning in April after a “complete rejuvenation…fully emerged from its chrysalis state.”255

Shown here along J Street circa 1960, the Fashion was started by ex–Texas Ranger John C. Keenan. Library of Congress.

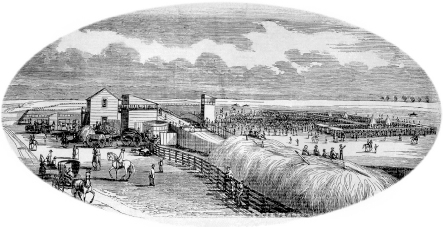

Keenan possessed more on his daily docket than just the Fashion. While a member of the Sutter Rifles and treasurer of Engine Company No.5, his primary diversion came as manager of the Sutter Race Grounds, located east of the city “between the old Stockton and Jackson Roads, near Harrigan’s Two Friends House.”256 At the time of the Gold Rush, horse racing’s American pedigree was already quite rich. Brought over to the eastern United States from England and France, the sport seamlessly meshed with the country’s agrarian roots, and as the population shifted westward, so too did racing. The first few regional tracks to open, San Francisco’s Pioneer Course and Sacramento’s own Brighton Jockey Club, did so in 1851. Races at the Sutter Race Grounds debuted in the spring of 1854 and included two horses owned by none other than John Frederick Morse, they being Lilly and Trifle.

A direct competitor to the Sutter was the Louisiana Race Track, located at what is now Twelfth Avenue and Franklin Boulevard, an area also known as Whiskey Hill because of the presence of two saloons. The Louisiana, managed by C.S. Ellis, opened for business in early 1855 as a trotting and racing course. For one dollar, spectators, many of whom came from as far as San Francisco, were granted access to all parts of the course. Ellis’s management style, however, came under criticism as he was accused of running a slipshod operation fraught with “a series of starts, balks, humbugs and tomfooleries that would disgust anyone who ever saw or had any idea of how such things should be properly conducted.”257 The Democratic Journal’s criticism was not without solution as it suggested that the Louisiana management visit Keenan’s Sutter Course to view “horse racing done up as it should be.”258

The Sutter and Louisiana tracks were direct descendants of the colorfully named Brighton Jockey Club. The BJC’s arrival was big news to many of the newly transplanted race enthusiasts from the east. Its grounds were massive, covering no less than 130 acres. The Brighton’s stewards, most notably John Sutter Sr., celebrated the track’s opening with an inaugural ball at the Orleans House in May 1851. When up and running, the track offered races in increments of one, two or three miles for four-leggers like Wake-Up-Jake, Wisconsin Chief, Lem Gustin, Black Swan, Cock Robin and Whalebone, to name a few. The BJC enjoyed a favorable run and was known to draw up to 2,500 spectators for a single event. However, in February 1852, it was plowed into a barley field, “leaving no traces of the track over which the fleet coursers so lately sped.”259 The earliest harvest from the newly planted grain was claimed by the Union to “have surpassed any we have seen the present season,” growing some six feet, eight inches in length.260

The Louisiana Racetrack had its own saloon and eventually became home to the California State Fair. Center for Sacramento History.

The Alhambra Saloon opened its doors in late December 1852 at 67 J Street, near Third Street, “phenix [sic] like, arisen from the ashes and still afloat.”261 L.N. Gibson of Pennsylvania was its proprietor, but his wife, Josephine, seemed to be the one who truly made the saloon go. Like Radford’s, the Alhambra was keen on serving up oysters “in every style.”262 It was also one of many saloons that offered ice cream, especially during the summer months. Upon receiving a gift of the sweet confection from Josephine, the Democratic Journal claimed that “the thermometer” fell “twenty degrees in the office upon its arrival.”263 The Alhambra started strong—strong enough to open a branch in the temporary village of Hoboken. However, by the spring of 1853, the Alhambra’s tenor changed. In July, the saloon was up for sale, the owner “desirous of leaving California.”264

In a notable twist, Mr. Gibson was not speaking for Mrs. Gibson. Josephine, also referred to as “Old Joe,” chose to stay in Sacramento, opening her own saloon on February 22, 1854, on Second Street across from the Wells Fargo and Company Express Office. The Capital Saloon, not to be confused with a business of the same name on J Street between Sixth and Seventh Streets, was a significant newcomer for one particular reason: it was owned by a woman, making it one of the first female-owned saloons in the city’s history.

In addition to a full bar, the Capital ensured “oyster stews, fried oysters, shelled oysters and clams, ham and eggs, tea and coffee and ice creams in season.”265 Josephine’s strengths were not simply culinary; she could also draft a catchy poem, as evidenced in one of the more amusing advertisements for Sacramento victuals out of the November 21, 1854 California Statesman:

Whether in homage to mail delivery or international communication, it was common for saloons to take on the names of trending events. Sacramento Public Library.

OYSTERS! OYSTERS!

FRESH OYSTERS, ALL PRIME,

To be served in quick time,

Either roasted or fried,

Stewed, pickled or pied,

As gentlemen wish

Who call for a dish;

Whigs, Democrats, Know-Nothings and all,

Please give us a call.266

By December 1855, Josephine had moved her saloon into a larger building formerly occupied by the Arcade Saloon, on 40 and 42 J Street, naming it, most fittingly, Josey’s Saloon.

Gibson wasn’t Sacramento’s sole female saloon owner. In fact, throughout the 1850s and early 1860s, we know that area saloons came under the ownership of at least nine other women.267 Jeanette Frank, Elizabeth Cooper, Betsey Bennet, Anne Marie Walteamath, Elizabeth Chappell, Bridget Hunt, Catherine Little and Sarah Oakley all held sole trader status as operators, meaning they formed the single, independent, decision-making entity for their businesses. The Eagle Saloon, located on Second Street near K, was under the sole operation of Mrs. T.C. Trotter. In addition to its full complement of liquors, the Eagle claimed to serve “viands…in such a manner as ‘to please the taste of the most fastidious.’”268 The English-born Trotter was a youngish twentysomething at the time of the saloon’s opening in 1853.

Despite the presence of these accomplished female saloon operators, the overall presence of women in city saloons, although not uncommon, had to have been outside the norm (proprietors or prostitutes notwithstanding). In 1850, women accounted for one out of every twelve California immigrants. In 1860, the number of female immigrants increased, although still amounting to only one out of three new Californians.269

Though almost exclusively incubators of manhood, saloons were not without female accommodation. Some spots, like the Orleans, provided the “ladies’ ordinary,” referred to in another source as “the wineroom in the back.”270 It was also said to be the first of its kind in the Sacramento area.271 The ordinary sought to sequester women from the standard bar area while providing so much of what was being enjoyed in the saloon proper. Moreover, because the thought of ladies pushing their way through the sacred “batwings” was not quite yet a palatable one to a large slice of the male population, more than one establishment created alternate or private entrances. Once in the saloon’s ordinary, women could eat, drink and leisurely chat away the hours.

In the less posh saloons of the city, women appear to have been treated as viable front door–entering customers. What is more, gender had no mitigating effect on a woman’s ability—like her male counterpart—to get drunk and disorderly. Charlotte King’s late summer 1861 drinking binge resulted in the discharge “of a pistol at a gambler, named Brooks, but without striking the object aimed at.”272 After she was dragged, kicking and screaming, from the saloon at Sixth and K, it was King’s contention that Brooks had cheated her out of ten dollars in a game of rondo. When Brooks attempted to remove King, she pulled the weapon from her “bosom” and fired wide of the lucky gambler.

We should also mention that women moved about Alta California with a certain measure of comfort. As historian John Boessenecker states, “Because they were so scarce, most Forty-Niners treated women not just with respect but with reverence, for they represented the mothers, sisters, daughters, wives, and sweethearts left at home.”273 Corroborating as much, between 1850 and 1861, nearly fifty-one men—statewide—were convicted and sent to San Quentin on charges of rape or attempted rape. Placed in a modern context, raw statistics would tell us that women are five times more likely to have violence perpetrated against them in the twenty-first century than during the Gold Rush era. It is perhaps the case that the same level of safety followed the female form into many of Sacramento’s Gold Rush saloons.

The Blue Wing also burst onto the saloon scene as a strong purveyor of the mixed drink or the cocktail, a uniquely American invention of the nineteenth century whose etymological origins go back to roughly 1803. Owned by Louisiana transplant E.L. Smith, the Wing, in the old confines of the Gem, stood at the corner of J and Second Streets at 29 J Street. Its name came from a distinctive characteristic of the golden eagle surmounting the entrance of the saloon: it possessed one blue wing. Smith’s menu of cocktails was diverse: Roman punch, lemon punch, mountaineers, strawberry juleps, pineapple punch, hock and sherry cobblers were just a few of them.

Turnbull’s, owned by Robert Turnbull, was located on Second Street. It was the first of Sacramento’s saloons to offer a drink known as the “Mountaineer.” The drink’s inventor—or so he claimed—was J.B. Brouilette from Louisiana. It is unclear what ingredients made up a Mountaineer, but a more modern version is composed of one ounce of orange juice, a quarter ounce of lemon juice, a half ounce of ginger ale, one and a half ounces rum, a quarter ounce of milk and one teaspoon of pepper. It appears that the drink was so popular that a Sacramento saloon located on K between Third and Fourth chose to name itself accordingly. In addition to spirits, Turnbull’s retained the services of a “superior French cook” who went far in ensuring a lunch table “supplied with the choicest Viands in the market.”274

The Marion House opened its doors in early December 1852 under the guidance of J.W. Stillman. Located at 43 J Street between Second and Third Streets, the Marion boasted full bar fixtures, fifteen rooms for lodging and six billiard tables with “balls and cues, always in good order.”275 The Marion seemed to possess an edge, one harkening back to the grittier days of the Mansion House. Such was the case on the evening of April 3, 1854. A number of men were sitting in the saloon, discussing a row that had taken place earlier in the day at Second and K’s Verandah. Things heated up when George McDonald, a baker from England, and James Turner exchanged “high words.”276 Near tragedy took place when McDonald took his pistol and fired a bullet into the back of Turner, entering “at the point of the left shoulder blade and ranging across the back, lodg[ing] inside the skin of the neck above the right shoulder.” After falling, Turner was carried to the drugstore of a Mr. Simmons at 48½ J Street. The Union reported the bullet to have been extracted not fifteen minutes after entering Turner’s body, allowing him to experience a smooth recovery. Two years earlier, in August 1852, the incorrigible Turner had been involved in a shooting at the Diana. When refusing to pay for his liquor, the saloon’s bartender “went to the end of the counter, got a revolver and discharged three or four shots at Turner,” one of which lodged in his neck. After being taken to San Francisco for the cooler weather, Turner went on to recover.277

A markedly more passive event at the Marion House, a qualified hook, took place in the spring of 1855 when Eclipse the “mammoth ox” was showcased to Sacramento’s most curious. According to advertisements, the six-year-old Eclipse weighed two tons and was purported to be the “largest animal in the United States.” It cost fifty cents for one’s bovine curiosity to be satisfied.278

The Marion’s clear trump in violence was the Arcade, located on J Street. The saloon debuted in January 1855 and did so looking for a fight.279 The first row occurred on January 13 between Charles Brockaway and D.C. Henderson. The latter was quietly playing cards when Brockaway jumped in and seized hold of Henderson’s money. As Henderson spewed “vile epithets,” Brockaway grabbed a stool “and so on.” Eventually, a police officer stepped in, separating the two. For their trouble, both men were fined twenty dollars each. Just days later, H. Whitcomb was enjoying his dinner in the Arcade when Owen McKim strolled into the saloon and “applied a most disgusting epithet to him.”280 With ire raised, Whitcomb retaliated with a “‘sog dologer’ in the frontpiece of Owen, which completely floored him.” Just as Whitcomb was about to take a stool to McKim, the police entered the saloon, arresting both men and fining them each twenty dollars. While Whitcomb was able to pay, it was reported that “McKim will probably have to work his passage.” A week later at the Arcade, William Barnes and J.P. Dillon “got up an exhibition of pugilistic powers” resulting in the arrest of both, but a stiffer penalty of twenty-five dollars was assessed to each.281 By mid-February, the Democratic Journal had had enough, claiming, “If rowdyism continues to increase in this saloon in the same ratio of the week past, public interest will require it be indicted as a nuisance.”282

The Arcade, however, lived because of its insatiability to a bevy of curious customers. The public could not deny its gambling allure, and the case of a very common figure in James Gudgeon illustrates as much.283 Gudgeon, a carpenter by trade and far from being a professional gambler, was reported by the California Statesman to have, on one Friday night, “bucked a little at faro.” After quickly losing $250, he turned to the dealer, a man named Barr, calling him a “thief.” Barr then “bunged his eye with a blow of his fist.” When the dust cleared, Gudgeon “came out decidedly second best, having a black eye, a broken finger and other minor injuries.” In front of the county recorder the following day, Gudgeon was fined $30 and Barr $40 “and trimmings for their pugnacity.”

Moving from brawling to brewing, an often-heard term during this time in Sacramento, especially when the weather warmed, was “lager beer.” The term applied to a style of beer and the name of more than one drinking establishment in the city. The lager-style drink originated in the Bavarian region of southeastern Germany and made its way to the United States in 1842. By the time of the Gold Rush, the lager—both within California and out—had become a popular alternative to the more traditional ale, so much so that in the fall of 1854, when the community of St. Louis ran out of lager beer, the headline of the Democratic Journal’s story on the crisis read “Horrible.”284 According to the same article, in the six months previous, St. Louis consumed an estimated eighteen million glasses of lager.

The term lager comes from the German verb lagern, meaning “to store.” After fermentation, lagers are typically aged for several weeks, even months, at a temperature of nearly fifty degrees Fahrenheit, sometimes cooler. The process helps leach yeasts and proteins, both of which effectively mellow the beer’s taste. As we remember, ales, the standard beer up to the advent of the lager, are brewed both more quickly and at a higher temperature. One true lover of the lager-style beer was California’s third governor, John Bigler, who was known to carry powdered soda and magnesia in his chest pocket to keep his stomach settled as he imbibed his brew.

Sacramento’s introduction to regionally brewed, lager-style beer came in the spring of 1853. The product was shipped from San Francisco and sold from a saloon located within Heywood’s Building on the corner of J and Second Streets. The San Francisco Saloon, originally known as the Beer and Billiards Saloon, of Germans Edward Kleibitz and Robert Green, on Fourth Street between J and K, also acquired brew from San Francisco’s Jacob Gundlach and his Bavaria Brewery in San Francisco. The debut of locally produced lager came in 1854 when Louis Keseberg opened the Phoenix Brewery at the southeast corner of Twenty-eighth and M Streets. Originally nothing more than a barroom, the refit Phoenix made an immediate impact on Sacramento. Not only did it establish a tasting room at 324 J Street, between Tenth and Eleventh Streets, but as described by the Democratic Journal in May, the Phoenix took alcohol marketing to a whole new level: “A new beer wagon, intended for the Brewery at the Fort, was paraded through the principal streets about ten o’clock last night, drawn by about fifty men and followed by a thirsty crowd. A pole was upreared [sic] from the center, bearing an American ensign, stiffened in the breeze and a band of music occupied the broad surface of the truck. There was probably a noisy time at the irrigation which was contemplated.”285

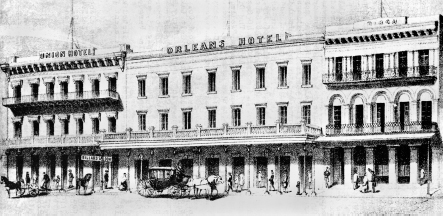

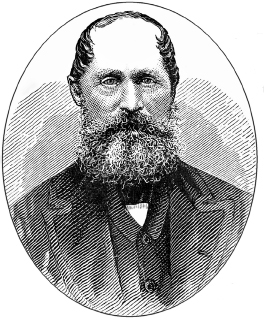

Louis Keseberg went from starvation with the Donner Party to opening up his own brewery, the Phoenix, in 1854. Sacramento Public Library.

As sales increased and the brewery expanded, prices dropped from seventy-five cents to a tasty sixty-five cents per gallon. In July, the Journal extolled the Phoenix’s “most excellent drink…supplying daily, hundreds of our citizens—they make nothing but the pure article.”286

In August 1856, Keseberg was arrested for assaulting an individual who entered the brewery. The intruder was reported to have threatened a Phoenix employee, but after Keseberg ordered him to leave the premises, a row ensued. Days later, the owner was forced to answer before the county recorder. The brewer’s “unbridled temper,” not to mention his questionable past, both stand worthy of discussion.287 Described by Heinrich Lienhard as “a tall, intelligent man of military bearing,” Keseberg was born in Prussia and came to the United States in 1844 with his wife, Phillipine. His decision to head to California forever connected him to one of the more infamous migratory disasters in American history, the Donner Party.288 Reports paint a character in Keseberg as anything but stable, adding that he possessed a “rapid, loud and ‘somewhat excited’ manner of speech.” The brewer was also accused by several emigrants of beating his wife.289 What’s more, near the beginning of the party’s journey, Keseberg was suspected of killing a fellow emigrant, a man named Wolfinger, for his money in the fall of 1846.290 Topping off the brewer’s sinister aura was the claim—by many—that he was the first person in the Donner Party to resort to cannibalism. In any case, after evading justice and then embarking on assorted ventures, including one as a riverboat captain, Keseberg settled in Sacramento and opened the Phoenix. In spite of his cannibalistic past, lager lovers didn’t give things a second thought—the Phoenix brew sold well. By late summer 1858, the brewery was turning out nearly 1,500 gallons of lager a week.291

Prussian-born Louis Keseberg was known to have a bit of an anger problem. Sacramento Public Library.

With the Phoenix well aloft, several businesses were eager to retail the brewery’s lager. J.H.C. Waltemath’s Lager Beer Saloon opened in May 1854 on the south side of J Street near Eighth Street, and Joseph Brown’s Lager Beer and Chop Saloon opened at 38 J Street in November, offering the “Best LAGER BEER in Sacramento.”292 In July, Henry Eisenmenger and H. Ehman opened the Sacramento Beer Cellar in the basement of a brick building on J between Sixth and Seventh Streets. It is described as “well-furnished and bountifully supplied with that excellent article, Lager Beer, with which the friends of the proprietors were regaled…with as much as they could drink.” The Cellar also served lunch and provided music through the company of a “fine brass band.”293 Appearing, by all accounts, above ground was the Lager Bier and Coffee Saloon on Second Street, between J and K. M. Elias, originally of New York, was the proprietor. In addition to “steaks, chops, etc, etc,” Elias offered a “Sacred Concert every Sunday evening.”294

Sacramento’s appreciation of the lager beer was a profoundly transnational one, as relayed by the Democratic Journal:

Germans and their direct descendants seemed, a short time ago, the only persons who appreciated its particular flavor, but now it is the drink of all sorts of conditions of men, from those who claim it as their national liquid down to the elliptical-eyed Celestials and dingy-hued Californians. Lager beer saloons are numerous on “J” Street; there is one at nearly every corner…The professional man, the merchant, the mechanic, the clerk; all are contracting a passion for the Lager Beer saloon and its concomitants.295

Lager’s cool, refreshing taste gave it an advantage over the heavier ale, more commonly consumed at room temperature. The location of lager-serving saloons in cooled cellars, especially during Sacramento’s summer months, proves far from surprising. With cooling technology still in its infancy, cellars were a cost-effective way to keep one’s product fresh and drinkable. It was not until 1859 that we have any indicator of an individual saloon utilizing an “ice closet” to store its lager beer. Klay’s Saloon, located on Fourth, between J and K, drew from its closet lager of the “best quality…as though it were ice itself.”296

Still, if one chose to stay at ground level, there were refrigeration options. The Sitka Ice House, located on Front and I Streets, was built at an estimated cost of $11,000 and featured double-thick, charcoal-lined walls.297 It was intended to hold up to one thousand tons of ice. When opening in the spring of 1854, each one-pound increment of ice was sold for ten cents. The Sitka’s presence was a revelation for saloons that, if not opting to cellar their goods, were required to venture into the Sierra Nevada for ice. The product, obtained from what was then the Russian territory of Alaska, was considered by the 1856 City Directory to be of “excellent quality and can be obtained at all seasons of the years.”298 An ice provider to follow the Sitka was the California Ice Company on Third Street, between I and J Streets.

An enjoyable lager beer needed to be cold, and if Sacramento was not pulling its ice out of the Sierra Nevadas, it was buying it from companies that imported chunks from Alaska. The California Ice Company was one such company. Sacramento Public Library.

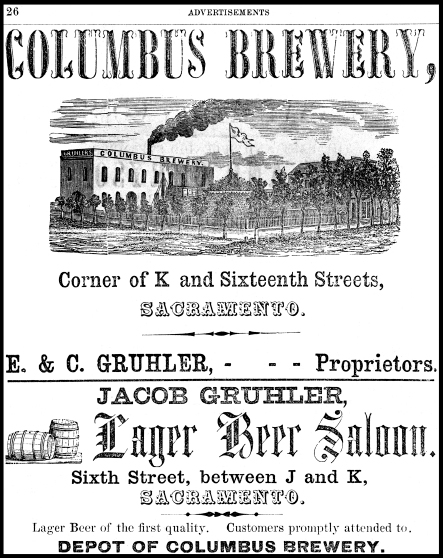

The Columbus Brewery, located on the corner of K and Sixteenth Streets, started lager production in 1853 under the guidance of brothers Elias and Christian Grühler, both hailing from the Baden-Wurttemberg region of Germany. By 1858, they were making 1,200 gallons of beer per week.299 At full production, the Grühlers employed two to three men to operate the tubs, as well as a cooper to construct barrels. Their primary distribution point was the Grühler Saloon, located on Sixth Street, between J and K.

An advertisement for the Columbus Brewery and its primary retailer, the Lager Beer Saloon, from the 1857 City Directory. Courtesy of the Sacramento Room Archives.

As the summer of 1853 descended upon Sacramento, the city found itself hosting a solid crop of 139 bars or drinking saloons, a far cry from the 208 recorded in 1851, but still a robust number considering the presence of fire not ten months earlier.300 Moreover, the city’s liquor wholesaling community had found some traction. By December, William A. McWilliams and Company, by all indications the city’s largest seller of alcohol, had reopened for business at 22 K Street between Second and Front. Its list of offerings, almost all imported, is impressive: Martel, London Dock and Otard brandies; claret; hock; sherry; champagne; Irish malt, Scotch and Monongahela whiskeys; Holland Gin; Jamaican rum; English ale; and porter. Even Guinness’s Dublin Porter could be found there.301 Other local sellers of alcohol included William Walker and Company at 115 J Street, between Fourth and Fifth; Despecher and Field at 57 J Street; and J.D. Mairs and Company on 97 K Street near the corner of Fourth Street.

As can be seen, the saloon community’s post-fire renaissance was a heady one. However, not all Sacramentans were pleased. The Whiggish Union exhibited its consternation by writing: “These places of resort will spring up, though never a church or dwelling house were built in the city. To see the number of decanters of bad liquor arrayed on dirty boards, with scarcely a shelter to cover them, would lead a citizen of Maine [referring to Maine’s prohibition legislation] to suppose that guzzling was the great object and aim of life in Sacramento. A little reform in this respect would be quite a credit to the city.”302

Based on the impact of the 1852 fire, as well as a crescendo of events on the national scene, it was easy to see why prohibitionists had hope. In 1851, the state of Maine became the first member of the Union to outlaw the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors within its borders. By 1855, thirteen of thirty-one states committed themselves to similar legislation. The news proved momentous for Sacramento teetotalers, prompting the city’s local chapter of the Sons of Temperance to both publish Maine’s liquor law and furnish California’s governor and each of the state’s assembly and senate members with a copy.

The Maine legislation inspired a series of lectures, meetings, demonstrations and several “dry” meetings. The most extensive display of good, clean temperance fun took place in late December 1853 under the guidance of the city’s Sons and Daughters of Temperance. The Union reported the party to possess “no lack of hilarity, vivacity, or of a free and full flow of life and spirit from the absence of wines, etc.,” and included that “the demonstration should satisfy us that intoxicating beverages are not absolutely essential to cheer the festive board.”303

In addition to the Sons and Daughters of Temperance, Sacramento became home to the youth-centered Cadets of Temperance in January 1852 and then in May 1853. Though separate in name, all groups met in the confines of the same place: Temperance Hall, located at 52 K Street. It was here that those intent on guiding public policy discussed the prospect of entering local and state politics. The first such effort was powered by a caucus held in March 1854. By April, Sacramento teetotalers had chosen Ben Essely for mayor. Josephine Gibson, proprietor of the Capital Saloon, was perhaps even feeling some impact of the prohibitionist traction, declaring that “the triumph of temperance has not caused [her] to ‘fizzle out,’ but [she] is ‘still at home,’ ‘alive and kicking’ and with the largest supply of the purest and oldest liquors in the vicinity of the Capital.”304

After the state legislature passed an act in May 1855 entitled “To Take the Sense of the People of This State…on the Passage of Prohibitory Liquor Law,” the temperance community was afforded a chance to see the effect of its lobbying efforts. In mid-September, the county voted on a liquor law that would “prohibit the manufacture and sale of all spirituous and intoxicating liquors, except for mechanical, chemical, medicinal and Sacramental purposes.”305 The results—2,195–1,493 against prohibition—were revealing. Sacramento was, at its heart, a truly “wet” city.306 The Democratic Journal referred to Sacramento as being decidedly in favor of the “ardent,” a reference to the oft-used term “ardent spirits.” It also was reported in the Union that, since the passage of the Maine Liquor Law, Rhode Island’s demand for “ardent spirits” had increased by 20 percent.307 Sacramento’s Sons of Temperance lamented the loss in the form of a torchlight procession in October 1855. Heading the group of 120 was a brass band that, starting at the corner of J and Tenth Streets, finished at the Reverend Benton’s church (Pioneer Congregational Church).308

In the decade’s latter years, efforts to restrain the sale and consumption of alcohol were recurring but generally ineffectual. Perhaps the most extensive and meaningful piece of temperance legislation was enacted in 1858, capping the amount of money to be paid for “the purchase of, or the sale and delivery of any spirituous or malt liquors, wine or cider, by retail or by drink” at five dollars.309 It sought to curb binging, as well as the proliferation of debt, vis-à-vis saloon accounts. The Union approved of the act, calling it a way to “keep the picks in the hands of miners and laborers and a good deal of poison in the bottles of shopkeepers.”310

Gaming’s time of reckoning had also come. Senator William C. Hoff, a Democrat from San Francisco, introduced a bill that sought the suppression and license of public gaming in general. In March 1851, anti-gambling proponents could finally experience some success on a statewide level when “An Act to License Gaming” passed both houses, making it high season for “mining the gamblers.” The law’s primary impact rested in the jurisdiction that it gave counties, requiring gaming houses to apply for—and purchase—licensing from county treasurers.

Licenses weren’t cheap by any stretch. For every three months, the licensee was required to pay $1,500 for three or more tables and $1,000 for fewer than three. The assessment applied only to San Francisco, Sacramento and Marysville, with other jurisdictions paying a markedly more reasonable $35 per month per table. Three-quarters of licensing revenue went into the state budget and one-fourth into county coffers. The act also allowed municipalities to perform further licensing and assessment as they saw fit. Also affecting the gaming landscape was the criminalization of French monte, thimblerig and lotteries, three J Street standards. The penalty for hosting the illicit games included three to six months in jail and a fine of between $500 and $2,000. Provisions of the act did not extend to billiards or bowling.311

In August 1852, one campaign sought the prohibition of public gambling on Sundays. “When will the citizens of Sacramento see the day when public gaming on the Lord’s Day will be suppressed?” asked the Union’s editorial voice, “Moralicus.”312 Though San Francisco, Marysville and Stockton all would enact laws to protect the Sabbath during this time, Sacramento would not follow suit until a few years later. Flaccid efforts like the proposed Sabbath ban proved the norm until the overall fortunes of gaming opponents seemed to look up in April 1855, when Governor Bigler signed into law a bill banning most banking games. In essence, anyone brave enough to open or cause “any gaming bank or game of chance…may be prosecuted by indictment by the Grand Jury of the county in which the offense shall have been committed.”313 In a turnabout from the 1851 law, billiards and bowling also fell under the bill’s purview.

Next, “upon evidence of one or more credible witnesses,” penalties assessed to persons “who shall deal” would not exceed $500, nor would they be less than $100 for the first offense. The same penalty applied to the owner of the gaming establishment unless it could be proven that he or she had no knowledge of the illicit act. Fine disbursement ensured that one-fourth of the revenue went to the district attorney of the county in which the offense was committed, one-fourth to the county’s treasury and the remaining sum being “equally divided among the various Orphan Asylums in counties where such Asylums exist and where there are no such Asylums, shall go into the ‘General School Fund’ of the county.” The act then ensured that “all notes, bills, bonds, mortgages or other securities or conveyances whatever” involved in wagering “shall be void and of no effect.”314 With the new legislation also repealing both the March 1851 “Act to License Gaming” and its April 1851 amendment, a huge dimension of public gaming in California was dead, with the personality of Sacramento and the general state’s saloon culture slowly reflecting as much.

As we’ve learned, the Arcade represented the very den that vice legislation meant to control or kill. The demise of John Reed, most of his fall having occurred in the infamous Arcade during the lead-up to prohibition, seems to have been a lightning rod for public anger and a clear illustration of gambling’s insidious effects. Reed, a twenty-two-year-old native of Steubenville, Ohio, was an employee of the State Journal and was well loved by colleagues, “esteemed for the generosity and affability of his disposition.” His darker tendencies led him toward “the hell on ‘J’ Street known as the Arcade,” where repeated losses and consequential liabilities left Reed penniless. The gravity of his indiscretions proved so unbearable that he opted to commit suicide through the ingestion of strychnine. The most chilling vestige of Reed’s fall came in the form of his farewell letter: “I HAVE RUINED MYSELF FOREVER BY GAMBLING AND THE APPETITE I HAVE FORMED FOR THE PERNICIOUS HABIT IS SO STRONG THAT I FIND IT IMPOSSIBLE TO QUIT.”315

Shaped by stories like that of Reed’s, the role of public sentiment in the suppression of gaming cannot be overstated. Sacramento and the state as a whole were growing to be more demographically and economically heterogeneous; the days of service outlets accommodating solely the reckless whims of miners, young and old, were supplanted by an era in which merchants, laborers and even families were demanding to be heard. The state’s demographic footprint in 1854–55 was clearly different from what it was just a few years earlier. As of late August 1850, it was reported that nearly 43,000 immigrants came through Fort Laramie; 92 percent of them were male, while the remaining 8 percent were women and children.316 The state’s population for that year was 92,597.317 Two years later, the state’s population crested at 255,122.318 Of this number, most residents were between the ages of twenty and forty, and over 90 percent were male.319 Before the end of 1853, however, 70 percent of those who arrived by sea between 1849 and 1853 (roughly 175,000 people) had left the same way.320 This dramatic shift—the departure of so many young men and, with it, the demand for drink and game—had a remarkable effect on the state’s saloon culture. In short, with the ebb of the Gold Rush, California was finally settling, as were its demands for vice. As stated by historian John M. Findlay, “Californians gradually redefined gaming as beyond the borders of respectability as they set about taming their society.”321

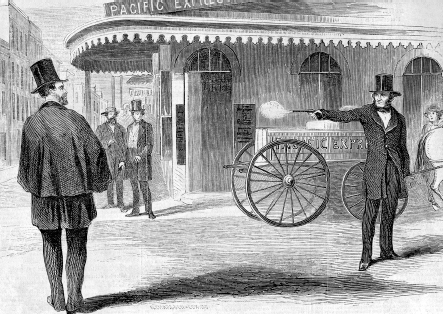

It is also true that the anti-gaming community sought to eliminate the longstanding fraternity of professional gamblers. Figures like Charles Cora symbolized a perceived scourge. Moralists, hoping to infuse puritanical East Coast ideas of right and wrong into California society, saw professional gamers as not simply outside the “borders of respectability” but as a clear threat to who and what guided the ethical and political compass of a community. In a situation similar to what followed the demise of Frederick Roe, a San Francisco Vigilance Committee sprang forth in November 1855 after Cora shot U.S. Marshal William H. Richard, supposedly in an effort to bolster Democrat James Y. McDuffie’s chances to be appointed to the then-open marshal’s position. The tacit voice of the committee was newspaper editor James King of William. Because of Cora’s association with McDuffie (both had gambled professionally in Marysville), it was King’s contention that gamers were colluding with Democrats to take control of the state. Although McDuffie freely acknowledged a brief career as a gambler during a time when it was a licensed and somewhat acceptable endeavor, he denied any connection to Cora. For taking a stand, King was himself assassinated in May 1856 by rival editor James P. Casey. King was quickly martyred to the anti-gambling cause, giving his committee sufficient moral leverage to hang Casey and Cora, both of whom were executed on May 22, 1856. In effect, Cora’s death proved to be a metaphor for change, for soon, instead of being looked upon as temples of glamour and escape, as they had been in 1850, gaming halls and their masters were viewed as roadblocks to social development.322

In Sacramento, public sentiment regarding King’s demise was profound. When the editor finally succumbed, church and fire engine bells rang throughout the river city, businessmen closed their stores for portions of the day and flags were hung at half-mast. Even the opposition, Democratic State Journal, conceded that King “was a vigorous writer and…correct in all his social relations. He is dead and malice is disarmed.” The paper did, however, question the unlawful executions of Cora and Casey: “We must have law; we must have courts of justice to settle the thousand disagreements which daily arise in society.”323 Not surprisingly, the Union (and again, reminiscent of the Roe debacle) sided with the committee, feeling that “law is defined to be a rule of action presented by the supreme power. The people are the supreme power, with us and when they calmly determine that their agents are unworthy of their confidence, that self preservation requires it, they have the right to re-organize upon the principles of democracy and administer justice and punish crime.”324

James Casey takes aim at rival newspaper editor James King of William. The latter’s death proved a watershed event for California gambling. Sacramento Public Library.

It is notable that while state legislation outlawed the hosting of most banking games, it neglected to assign equal penalty for playing such games. This element seems to typify the irresolute character of much of California’s anti-gaming legislation during the decade, which, according to Findlay, “did not outlaw every kind of game, proved difficult to enforce and provided mainly light penalties. Government found it hard to deter citizens from wagering at their favorite diversion, for gaming was deeply ingrained in the population.”325

Although not much documentation exists on the Metropolitan Saloon, an amusing anecdote speaks, in part, to Findlay’s point that Californians would gamble habitually, regardless of legality or, in this case, common sense. It involved a bet at the Metropolitan between two miners on their adeptness “at throwing a missile at a mark.”326 The bet amounted to $1.50 and would hinge on who “could hit the large mirror behind the bar with a lager beer glass thrown from a distance of 20 feet.” Within seconds, “the lager beer glass crashed into the mirror and made it a wreck of broken reflections.”327 The happy thrower claimed his winnings, more than pleased to pay the $170 required to replace the mirror. An equally telling story comes from the November 20, 1860 Union, which talks about the gaming activities of pupils at Franklin School who “spend a considerable portion of their time with a dice box in playing poker-dice for marbles. They appear to be lamentably familiar with the rules and slang phrases of the gaming table and may possibly be contracting a stronger taste for dice than for books.”328

Concurrently, we see a growing number of diversions in Sacramento pulling citizens out of gaming houses. Stockton, for example, in April 1854, rejoiced in the closure of its version of the El Dorado on the corner of Centre and Levee: “Yesterday, carpenters were engaged in dividing its capacious dimensions into stores…Within the past year much has been accomplished toward placing our city in a healthier and higher position than heretofore. The great accession to our female population and children has done so much in influencing these results—school houses and churches have taken the place of gaming saloons.”329

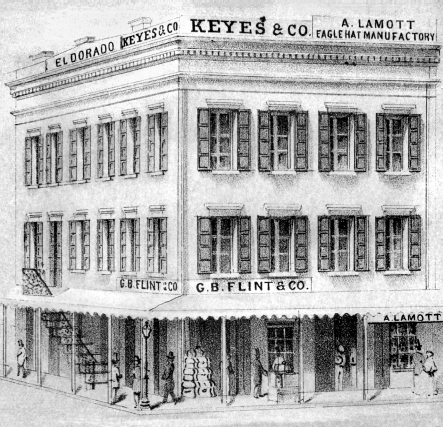

The same refit of gaming saloons was occurring to the north as well. In late 1854, the El Dorado, once the city’s “overwhelming gambling vortex,” was put to use “for better purposes” as it became the home to Keyes and Company Clothiers and Collins and Company Hatters, which instead of dealing cards was dealing hats made of “Rocky Mountain Beaver.” By this time, Rueben Raynes was fully out of the picture, now placing his efforts into the Fashion. Eli Skaggs, a twentysomething from Missouri, took control of the El Dorado at the price of $30,000.330

By virtue of a license it had received from Sacramento County, the Arcade was able to continue its gaming operations through July 1, 1855. Arcadians (a term referring to those operating or frequenting the saloon), perhaps attempting to diversify their offerings and ceremoniously open a new chapter in their history, hosted a “ball” on July 11. It was interrupted by an all too common altercation between two men that resulted in arrests and the shooting of a policeman.331 When the saloon finally did close, James J. Rawls erected a two-story brick building in its place, its new role being that of a market for the sale of meat and vegetables.

With the swoon of gaming, several more wholesome diversions scurried forth to entertain Sacramento. Theaters were a well-established alternative. By 1855, the Forrest and Sacramento Theaters were showing everything from Macbeth to Brutus, starring the earlier-mentioned Edwin Booth. By December 1853, Sacramento had its own debate and lecture club, the Lyceum, which tackled compelling questions of the day like: “Would the donation of public lands by Congress for building the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad be legal and expedient?”332; “Would it be expedient and Constitutional to enact a law in this state, enforcing a better observance of the Sabbath?”333 and “Was the French Revolution of 1793 and the Reign of Bonaparte a benefit to France?”334 Even the feasibility of “abolishing capital punishment in California” was debated.335 The Lyceum’s home was the Suwanee House (born in January 1852), which boasted a “large bar and dining room.”336 Athletics were enhanced with the birth of the Sacramento Turnverein Gymnastics Society. The Turnverein, whose origins can be traced to nineteenth-century Prussia, not only promoted physical health but also sought to engender social, patriotic and political activity. Sacramentans also could find entertainment and sanctuary with the Sacramento Philharmonic and the Sacramento Musical Society, both of which provided parlor concerts to the general public. Finally, the circus was an undeniable part of early city entertainment. With an association going back to the city’s origins, Joseph Rowe’s Pioneer Circus was quite the spectacle. An array of horse-riding tricks, tightrope walking, “antipodean feats” and the obligatory clown made Rowe’s circus a huge draw.337

The last incarnation of the El Dorado Building, which went from gambling den to business center. Center for Sacramento History.

Despite the extent of the aforementioned legislation, other forms of gambling continued unaffected. Horse racing had been a vibrant feature of Sacramento’s gambling culture and was far from being outlawed. As early as 1851, one could wager on bullfights being held in Washington and what would become West Sacramento. By 1854, bull and bear fights were being held, one pitting “a wild California bull and an immense grizzly bear said to weigh 1,600 pounds” against one another.338 One match, held in April 1856, between bear and bull drew 2,500 people to the city’s amphitheater. There was also the allure of dogfights that took place at the corner of Second and K Streets during the summer of 1856. It was reported in the August 15, 1856 Democratic Journal that during this period, up to five matches were being held daily.339 From the odd to the bizarre, wagers were even tendered on dog and badger fights. One organized affair of “badger baiting” came off in December 1858 when John Legget’s dog, Leo, took on a badger in an alley between J and K and Front and Second Streets. Spectators were admitted for a sum of fifty cents to see the sad ordeal that lasted ten minutes. The result was a severely mauled Leo, both in the chest and side, with “the badger being apparently uninjured.”340

Perhaps the most inventive gamble came off in late May 1857, courtesy of Engine Companies No. 1 and 5. The scenario pitted each group’s fire engine against the other in a race down M Street, from Twenty-first to Ninth, with the stipulation that the company “that runs the distance in the least time wins the wager.”341 By all indications, this was truly a citywide event; a reported “two or three thousand persons present,” most of whom gathered at either the start or finish lines and at the corner of M and Tenth Streets, were greeted with beer wagons and fruit stands. The engines, each weighing more than three thousand pounds, were pulled by a limit of twenty-five company members. When the challenge ended, the Knickerbockers stood victorious with a time of six minutes and fifty-two seconds. The Confidence Boys were barely bested at a time of seven minutes and five seconds. The wager between companies was $250, with no telling how much money changed hands between those in the general public. On a related note, since the summer of 1854, firefighters had had their own saloon, fittingly called the Hydrant. A brief advertisement implored those fond of “fun, fight, or fire” to quench their thirst at the new saloon, located next door to the city’s No. 3 Engine House on Third Street between K and L.342

Even with the departure of the Arcade and others like it, saloons persisted to be places of violence. Keenan’s Fashion suffered a stretch of violence starting in spring 1855. The most disturbing incident took place in early September.343 The fight appeared typical until the “two of the more enthusiastic individuals” were pried apart and it was found that “the nasal appendage of one” was “being firmly held by the dental organs of the other.” Perhaps this was the simple migration of Arcadian ire from one saloon to another, but this had to be far from the kind of Fashion that Keenan envisioned, especially with various physical renovations in play. Regardless, the new Fashion was complete by September, with a new address at 29 J Street. A saloon and billiards room occupied the first floor, while on the second, one would find sleeping apartments. Courtesy of the city’s Eureka Foundry, the signature design feature of the new Fashion was an iron façade striking a “unique pattern” of recessed Greco-Roman columns.344 In June 1856, Keenan ceded half the saloon’s control to James “Jimmy” Gunning; by July, Gunning held sole possession of the Fashion. In his late thirties at the time of purchase, the Ohio native guaranteed to “spare no pains to make his Saloon ‘THE FASHION’ of the city.”345