Chapter 5

THE EBBING TIDE OF THE GAMBLING SALOON: 1857–60

In January 1857, a curious resident of Sacramento escaped from a saloon on Second Street. “Jocko” the monkey, a trained fixture at an unnamed saloon, broke out and immediately scampered east, where he made his way to the roof of the Western Hotel on Tenth and K. It was there that “he amused himself looking into windows, climbing up and sliding down the awning posts and performing various antics to the infinite amusement of a crowd on the opposite side of the street.”346

If 1857 came in like a monkey, what would the rest of the year be like? The temperance movement again reorganized and added to its ranks. One addition—the Cold Water Army—was led by the curiously named G.I.N. Monell. The group’s ranks were stocked with an energetic and “goodly number of petite specimens of humanity of different ages, sizes, and sexes.”347 The Cold Water Army was reinforced by an anti-swearing society, housed at the corner of J and Eighth Streets. At least in the early going, the society funded itself by assessing monetary penalties to members that swore at five cents a transgression.348

Further moral jostling took place during the spring and summer of 1858. As March appeared, the state legislature’s ninth session approved an act “for the better observance of the Sabbath,” making it a misdemeanor to “[on Sundays] keep open any store, warehouse, mechanic shop, workshop, banking house, manufacturing establishment, or other business house for business purposes.”349 A notable exception, however, related to taverns and restaurants, which the act would “not apply to or in any manner affect.”350 Accordingly, on the first official day of action, in early June, several saloons—unaware of how the law was to be interpreted—held regular hours. The next day, proprietors Whitemore, Lothamer, Kleibitz & Green, Harris, Cody, Benjamin, Trestler, Hector and Newman were all arrested for violation of what would become known as the Sunday Law.

Justice C.A. Hill’s decision to recognize saloons in his interpretation related to (1) saloons being places of business and (2) his thought that “it could not be the intention of the Legislature that keepers of drinking saloons should be allowed to expose for sale and sell their merchandise—cigars, liquors, etc.—when the sale of the same is prohibited at other places.”351

Coming to the saloon owners’ defense was attorney Joseph W. Winans, who believed the law to be unconstitutional. With the law not on the books for even a month, the California Supreme Court agreed, striking the act down. It felt that the legislature was usurping its popularly granted powers and infringing “upon the liberty of the citizen by restraining his right to acquire property.”352

A lofty term like “liberty” used in reference to the saloon is significant, especially when looking at the social and legal influence of Sacramento’s saloon community. Their defiance found organization in 1861 with the formation of the Sacramento Liquor Dealers’ Association, which held its first meeting at Stanford’s Hall at Third and K. Included were names like Jacob Remmel of the Metropolitan Saloon; Joe Harris of the self-styled Harris’s Saloon; the Fashion’s John C. Keenan, standing as the group’s first president; and W.J. Cady of the Colonnade, its vice-president. Willingness to challenge the Sunday Law’s legality was the sole requirement for admission to the group, which went on to nominate and endorse candidates for local and state offices.

It is here that the steady infusion of Germans and other Central, Southern and Eastern Europeans to Sacramento, and its general effect on the city’s moral prospectus, holds significance. Simply put, the Germanic-style Sunday of after-church drinking, dancing and general Gemütlichkeit ran contrary to the mores of the pious, puritanical sectarians of older American stock who saw Sunday merrymaking as profane. Ironically, the same Americans who sought a dry nation and penitent Sundays were the ones who were both fighting against slavery and promoting equal rights. It’s not a stretch to say that the looming Civil War shifted the puritan focus to keeping the Union together and elevating America’s former slaves and away from prohibition. Even still, the prohibition movement had not been quashed; rather a slow, droning Kulturkampf over alcohol consumption would last well into the next century, accented by the Eighteenth and Twenty-first Amendments.

Anton Miller made the Ohio Brewery go, and his wife made it go after he could not. Sacramento Public Library.

Maintaining a Teutonic theme, the late 1850s saw additional names added to Sacramento’s list of breweries, the most important being the Ohio Brewery, located between Sixth and Seventh Streets and F and G Streets. Advertisements started to appear for the business in late 1855 but were found with somewhat greater regularity into 1857. The owner of the brewery—previously known as the Union Brewery—was a K. Stuelinger. His sales agent was Anton Miller, a native of Baden, Germany, in his mid-fifties. Also near the beginning of 1857, the Ohio established a saloon much closer to Sacramento’s commercial heart on Fifth Street between J and K. Near the end of 1858, the brewery was producing, on average, about five hundred gallons of lager per week.353

As Miller soon gained total control over the Ohio, the brewery’s operations expanded. He poured some $22,000 into the brewery in 1860. The most salient addition was a 32-foot by 82-foot beer hall “set aside for accommodation of Societies or parties who wish to assemble.”354 It also appears that one of the brewery’s two cellars—each measuring 30 feet by 50 feet—was refit by Miller to serve as a saloon. The brewery itself was large at 30 feet by 162 feet and three stories in height, making it the largest in the city. It was also large enough for Miller to make his home there.

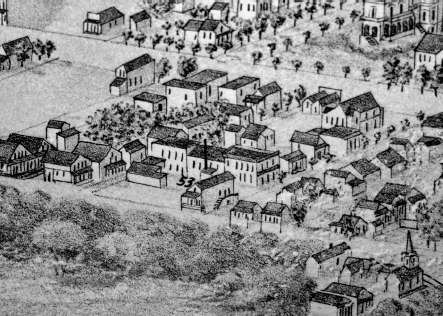

Taken from August Koch’s 1870 birds-eye view of Sacramento, the Ohio Brewery sits on the shore of China Slough. Sacramento Public Library.

Also appearing on the scene in 1857 was the Tiger Brewery, located at K and Thirty-first. Originally known as the Franklin Brewery, it was constructed sometime after 1853 by German immigrant Peter Yager. After this time and prior to 1857, it came under the ownership of James Rablin, originally from Cornwall, England, via Illinois, and Robert O. Smith, a native of Wisconsin. It would be their choice to give the brewery the fearsome feline moniker.

Until March 1858, the Tiger produced only lager beer. However, Rablin, Smith and company saw their brewing niche residing in both English and cream ales. Touting its Rablin’s Tiger Ale as the “Greatest Beverage of the Season,” the brewery was confident enough in its product to “challenge comparison with any Ale made in the state.”355 The Democratic Journal corroborated the boast in feeling that the “rich flavor, foaming appearance and cooling qualities recommend it more effectually than anything we can say.”356 By the spring of 1859, the Tiger’s lighter ale, also known as “Smith’s Sacramento Cream Ale,” was “favorably known in different parts of the state.”357 The primary competitor for the cream-ale market was the Bay Area’s Albany Brewery. Porter also was coming into production at the Tiger by around the same time. Eventually, because of its rededication to English-style beers, the business would rename itself the English Brewery near the end of the decade.

German contractor Peter Yager built the Franklin Brewery. It would soon take on the moniker of Tiger Brewery. California State Library.

The Tiger’s primary distribution point was Rablin’s Exchange, located at the corner of Tenth and K. The Exchange had always possessed the ability to board patrons, especially teamsters who could make use of the business’s “hay yard and stables” and fresh water.358 It also served as a polling place in 1852 for the city’s Third Ward.

As for Keseberg’s Phoenix, by 1858, it had started to diversify its production to include more than its signature Lager Beer. The expansion of the brewery would include—like the Columbus—a distillery, which meant the production of malt whiskey “made of the finest quality of Malt, by an experienced Distiller and pronounced by the best judges as equal to the imported Scotch or Irish Whisky.”359 Keseberg went as far as making it possible for potential patrons to sample his products by visiting the brewery or the Lady Adams Co., on K Street between Front and Second.

By midsummer 1858, the city’s five lager breweries were going strong, producing some 7,800 gallons of beer per week.360 While half of this amount was consumed by Sacramento itself, most of the other half was sent to surrounding mines, with a smaller amount being sent to a few cities to the south. The Bay Area remained a largely impenetrable market, as its nineteen breweries were more than enough to keep Sacramento Valley beers from crossing the Carquinez Strait.

Perhaps it was an omen when, in the spring of 1858, William McCall accidentally shot himself in the foot after dropping his gun on the floor of the reading room, but financial woes took their toll on the Orleans, especially after Joseph H Virgo took control of the operation from Hardenbergh.361 The once seemingly irrepressible Orleans was forced to close in April 1859. In the fall of 1859, a sad epilogue was written to the Orleans saga with word arriving that Count Bidleman was ill. Family members rushed to San Francisco to be by his side, but by November 9, Bidleman had died from what the Union described as a “disease of the heart.”362

We have spoken at length about the heterogeneous nature of Gold Rush Sacramento. One ethnic enclave to feel an acute streak of tragedy as the 1850s droned on was that of the Germans. Initial events centered around the person of Maria Rupp, a twenty-five-year-old beauty from the Hesse region of western Germany and operator of the Sacramento Beer Saloon on K Street between Third and Fourth Streets. Maria had been running the prosperous saloon since January 1856. That would change, however, on the evening of November 18, 1857. Rupp, while playing the saloon’s piano, was stabbed in the chest with a butcher knife. She was alert enough to call for a physician but was dead within fifteen minutes.

The killer was a German named Peter Metz. Other than the fact that he was a cook and that his age was between thirty and thirty-five, not much is known of him. He was friendly with Maria, but their relationship was strained by Peter’s unrequited affections. Several times, he had asked for her hand in marriage, each time being rebuffed. On the day of the murder, Metz had told John Zwicker, owner of his own saloon on Third Street, that Maria had agreed to marry him. The claim seemed unbelievable to Zwicker, who was chilled over by Metz’s ominous comment: “If she did not have him she would not marry anybody else; that she should die first.”363 So convinced was Metz that his romantic fortunes had turned that he ordered an entire bottle of wine and drank “to his marriage and future wife.”364 He also acquired the notion that he would take control of her business on the following day. His last words to Zwicker prior to proceeding to Maria’s were simply “that he would go over and see if the business was all right.”365

A few days later, Maria’s funeral service was held at the Saint Rose of Lima Catholic Church on Seventh and K Streets. Beloved as she was, her cortege numbered twenty-three carriages, buggies, etc. Pallbearers wore white scarves and white roses. After a service conducted by the Reverend Father Cassin, her body was transported to the City Cemetery, “where a requiem was sung by a quartette of German vocalists.”366 Maria was gone, and the trial of Peter Metz went on for weeks until he was found guilty of murder in the second degree. He was transported to the state prison at San Quentin, where he would serve out as much of a life sentence as was naturally possible.

The headstone of Maria Rupp. As a darling of Sacramento’s close-knit German community, her untimely death devastated the lives of many. Sacramento Public Library.

The ordeal of Maria’s loss, however, was not yet over. After a short stay at San Quentin, Metz’s odd behavior was enough to have him transplanted to a “lunatic asylum” near Stockton. Soon after arriving, he escaped, making his way up toward Marysville. Although being spotted by several locals, he was able to elude capture. After getting as far north as Siskiyou County, Metz was seized and returned to the Stockton asylum. It was reported in the Union that he took the matter “very coolly,” contentedly remarking that all of the return travel expenses would cost him nothing.367

The next venue for Germanic sadness was the Father Rhine House. Located at 268 J Street between Ninth and Tenth, it was owned by A.J. Bayer, a German from Hannover. His desire to ensure a good time for all of his customers rose to his detriment in the winter of 1857. It was the sentiment of Bayer’s immediate neighbor, the Philadelphia House, that the “dancing, music, hilarity and consequent noise” proceeding “long after midnight and the boarders of the Philadelphia House, which stands adjoining, have consequently been much disturbed.”368 It was also the Union’s contention that Bayer ran the headquarters of “all girls who follow the occupation of street musicians,” or what may appear to be antebellum music groupies.369 The paper went on to say that “dancing went on whether one of these strolling musicians chanced to present or not and that sometimes a white and at other times a black fiddler was engaged.”370 Regardless, the Father Rhine had a reputation that Bayer was seemingly far from disputing or changing, as the Father Rhine’s clear mission was to enable the unbridled merrymaking that comes with the German tradition of Gemütlichkeit. Accordingly, a few years later, in November 1860, the Father Rhine was up to its old tricks. At eight o’clock in the evening, friends of the proprietor gathered in front of the saloon “armed with tin horns, tin pans, bells, brass kettles, whistles and all uncouth implements that could be thought of for the production of the most horrible noises.” Such went on for over an hour, at which time the group dispersed. Again, the Union demanded that “enough was enough, even of a good thing.”371

It was not long before revelry turned to sadness for many of those who knew Bayer and the Father Rhine. On an early spring day in 1861, C.M. Tubbs, a young farmer, found a dead body floating on the Yolo side of the Sacramento River, just south of present-day West Sacramento. It was A.J. Bayer, “lodged among willows near the shore.”372 Reaching his latter forties, the saloonkeeper was survived by a wife and daughter. The backdrop of Bayer’s melancholy and resulting suicide resided in the stuff of both tragedy and modern tabloid. Prior to the discovery of his body, Bayer had been missing for more than two weeks. A witness, F. Haug, revealed that Bayer, under heavy intoxication and with tears running down his face, claimed that he would not see his fiftieth birthday. Bayer’s downfall came with the seduction and eventual impregnation of a young girl who had been living with his family. The details of the incident were revealed when Bayer was arrested along with his wife and mother for attempting an abortion on the young girl.

In the late summer of 1857, John C. Keenan was back at the Fashion, but he was not alone. His partner this time would be William M. Metzler. However, just days before the reopening, on July 27, near tragedy struck the Keenan family. At their home, near the corner of Fourth and N Streets, Keenan and his wife, Rosana, were readying for bed. As Rosana refilled a camphene-burning lamp, the pouring canister exploded, sending burning liquid all over her. The damage done—burnt breasts, arms and hands—was severe, but a quick-to-the-scene Keenan prevented so much more from happening by covering his wife with a blanket and extinguishing the flames.373

Keenan’s life then took a few more interesting turns. In May 1858, he boarded the steamer Eclipse out of Sacramento, bound for the Fraser River, which was experiencing a gold rush of its own. The prospects of the Fraser, located in lower British Columbia, Canada, were enticing enough that he and others were intent on making “a tour of reconnaissance.”374 While abroad, Keenan and his wife adopted three children: James, Jennie and M.J. Perhaps the need for a more steady line of work forced Keenan’s brood back to Sacramento. In any case, by June 1860, Keenan and a new co-owner conducted a private reopening of the Fashion.

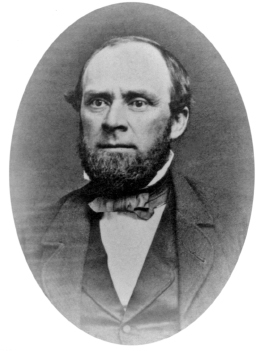

One of Sacramento’s early renaissance men, John C. Keenan died young of a heart attack while walking the stairs to his San Francisco apartment. Sacramento Public Library.

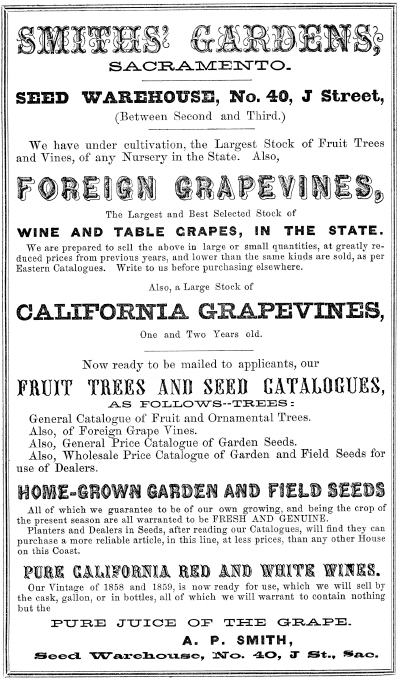

Also at this time, the Sacramento region was, at last, finding its wine-growing legs. By 1857, the state as a whole had pushed its annual production to a prodigious 246,518 gallons, compared to 58,055 in 1850.375 Smith’s Gardens made its expected contribution. It was Mr. Smith’s firm belief “that wine is soon to become the first great staple of California and that our valley, together with the foothills, are particularly adapted to the culture and rapid growth of the grape.”376 In late summer 1860, Smith’s arsenal of grape types included the following: Black Hamburg, Black Prince, Black St. Peter’s, Grizzly Frontignan, Muscadine Royal and Muscat Cannon Hall. He could also claim the cultivation of roughly 10,500 grapevines.377

A.P. Smith’s horticultural efforts were set at his gardens two miles east of Sacramento proper along the American River. Sacramento Public Library.

Wilson Flint was an early grower of wine grapes in Sacramento, just south of the central city along the Sacramento River. California State Library.

Closer to the city center, the Grühler Brothers’ vineyard, located on K Street between Fifteenth and Sixteenth, was highly regarded for its “scientifically trimmed” vines and “abundance of fruit.”378 And just south of Sacramento, at the ranch of J.G. Almard, the muscat grape was being grown “much fairer and larger than the Mediterranean grape, esteemed so great a luxury in the east.”379 Also near Almard’s was the vineyard of Wilson Flint, where “cultivated on rich alluvial soil” one could find the following varieties of grape: White Muscat of Alexandria, Purple Damascus, Black Zinfandel, Catawba and Black Hamburg.380

The first appearance of locally produced wine in a Sacramento saloon was recorded in August 1859. Noted for its “genteel, quiet and comfortable character,” the Metropolitan Saloon, on J Street and Third, served a California Red, vintage 1858. It was manufactured by Jacob Knauth, whose vineyards were part of the Sutter Floral Garden, in effect since 1851 and located on the corner of J and Twenty-ninth Streets at Sutter Hall.381 According to the Union, the wine “was pronounced excellent. We hope to see the time when the…prevailing drink will be our native wines and have no doubt that Sacramento County will be able to supply sufficient thereof for home consumption.”382

With wine flowing, Sacramento’s exotic saloon menagerie grew in kind, including a South American anaconda that, in June 1859, escaped from its box.383 The massive reptile had been on display at a K Street saloon for several days. For roughly a twenty-four-hour period, city residents were on edge with rumors that a child had been swallowed. Such hearsay persisted until a wagon and its frightful—and likely frightened—cargo was found on L Street, where it was captured.

In the mid-1850s, the Mountaineer House drew patrons with “a grey eagle captured on the Sierra Nevada.”384 The bird appears to have been a total spectacle, receiving “the attention and compliments of visitors with becoming dignity.” Patrons were able to interact with the bird by feeding it various meats.

The late 1850s also saw new entries into the saloon fraternity. One of the more popular was the Sazerac, owned by native New Yorker John C. Combes and located on the corner of Second and J. The saloon’s name refers to what may have been the nation’s first mixed drink. Born in New Orleans by druggist/mixologist Monsieur Antoine Peychaud, the Sazerac was a compounded mixture of cognac, sugar and aromatic bitters. As time went on, American rye and whiskey were substituted for Peychaud’s French cognac.

An amusing tale of culinary lust came out of the Sazerac in late 1857.385 Like many saloons, it possessed an oyster bar. The saloon’s owner furnished a new employee with a key so as to open the saloon early for preparation. When morning came, the new employee was nowhere to be found and the entire stock of oysters had been consumed. Less the oysters, in the summer of 1858, the Sazerac moved into a new brick building on J Street. We benefit from a detailed description provided by the Union. The new saloon covered an area of twenty-eight feet on J Street and fifty feet on Second. It included two aboveground floors, plus a cellar that was seven feet deep. The interior was “elegantly fitted, being elaborately and tastefully painted in fresco, ceiling and walls. Conspicuous in the bar is the sculptured head of a lion, in marble, from the mouth of which several fine jets of water are constantly playing into the marble basin below.”386

The close collaboration of contractors, so necessary in the construction of a saloon, is illustrated through the Sazerac: architect, M.F. Butler; builder, John Voorhies; mason, Walter Prosser; ornamental painter and designer, William Sefton; painters, Noonen and Co.; marble work, P.T. Devine; and plasterer, W. Mara.

Just months after opening, the Sazerac was hit with violence. The encounter between J.J. Watson and W.H. Taylor started off pleasantly enough.387 After Taylor threw twenty dollars in gold pieces onto the bar to pay for drinks, Watson countered that such wealth should enable Taylor to pay the money he owed him. After Taylor remarked that the owed sum was only fifteen dollars and that that it had already been repaid, Watson snapped, striking Taylor “about the head and body, breaking the bones of the right leg between the knee and ankle.” Once saloon-goers intervened, Taylor was taken to the Orleans House for medical care.

By late 1860, the Sazerac was offering “newspapers from all parts of the state” and had become one of the first saloons to offer a free lunch, served up every morning at eleven o’clock.388 The free lunch’s origins appear to rest, in part, with the advent of commercial drugs and their impressive physiological effects, often matching or surpassing those of alcohol. The Saint George Drug Store at Fourth and J, R.H. McDonald and Company at 139 J and Redington and Company in San Francisco offered an assortment of elixirs—Davis’ Pain Killer, Baker’s Pain Panacea and Moffat’s Bitters were just a few. It’s not known how much alcohol content actually resided in the aforesaid “medications,” but some, like the “locally produced Marvelous Remedy for Man and Beast,” could be composed of as much as 70 percent alcohol. Such a robust alternative to liquor portended a potential loss of market share for the city’s saloons. The salooning community’s counterpoint was the enticement of free food, which, of course, wasn’t completely free. In return for a meal, patrons were expected to purchase a minimum number of drinks. Without compliance, someone tantamount to the modern-day “bouncer” would remove the freeloader, which meant that bartenders, like in any other era, were not selected for their weak frame but for brawn.389

For those already accustomed to paying for a daily drink or two, what would come to be known as the “free lunch” proved a boon. One of the first Sacramento saloons to offer the free lunch was the Pearl. Operated by Charles Voigt and located on Third Street, it was called a “beautiful and neatly furnished saloon” by the Democratic Journal.390 Established in the spring of 1853, it was originally known as the Eastman, named for its first owner, W.A. Eastman. By July, however, the catchier Pearl moniker was applied. The saloon’s advertisement in the 1854–55 City Directory tempted readers with free portions of oyster, chicken and gumbo soup.

The free lunch’s reign was a long but not indefinite one. While 1919’s Volstead Act may have devastated the alcoholic punch of Western saloons, it killed the free lunch. And although repeal had a somewhat rehabilitating effect on the saloon industry, it clearly was not the same place that it used to be. The free lunch became an amusing footnote of history and went on to be nothing more than a convenient little idiom. Moreover, today’s peanuts and occasional bowl of crackers are a far cry from the nineteenth-century saloon’s impressive selection of smoked oysters, cold cuts and terrapin soup, the last offering a common free lunch sight at Keenan’s Fashion.