The first step in choosing the right networking API is to decide on the nature of the communication your application requires. There are many different styles of distributed applications. Perhaps you are building a public-facing web service designed to be used by a diverse range of clients. Conversely, you might be writing client code that uses someone else’s web service. Or maybe you’re writing software that runs at both ends of the connection, but even then there are some important questions. Are you connecting a user interface to a service in a tightly controlled environment where you can easily deploy updates to the client and the server at the same time? Or perhaps you have very little control over client updates—maybe you’re selling software to thousands of customers whose own computers will connect back to your service, and you expect to have many different versions of the client program out there at any one time. Maybe it doesn’t even make sense to talk about clients and servers—you might be creating a peer-to-peer system. Or maybe your system is much simpler than that, and has just two computers talking to each other.

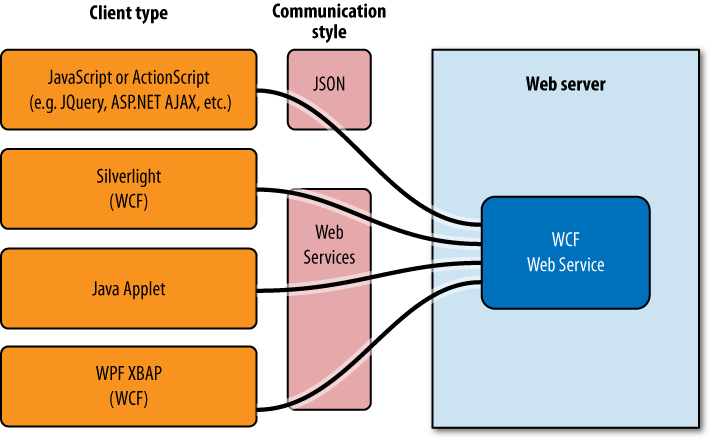

WCF is a flexible choice here, because as Figure 13-1 illustrates, you can make a single set of remote services accessible to many common browser-based user interface technologies. A WCF service can be configured to communicate in several different ways simultaneously. You could use JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), which is widely used in AJAX-based user interfaces because it’s is a convenient message format for JavaScript client code. Or you could use XML-based web services. Note that using WCF on the server does not require WCF on the client. These services could be used by clients written in other technologies such as Java, as long as they also support the same web service standards as WCF.

Looking specifically at the case where your web application uses C# code on the client side, this would mean using either Silverlight or WPF. (You can put WPF in a web page by writing an XBAP—a Xaml Browser Application. This will work only if the end user has WPF installed.) If you’re using C# on both the client and the server, the most straightforward choice is likely to be WCF on both ends.

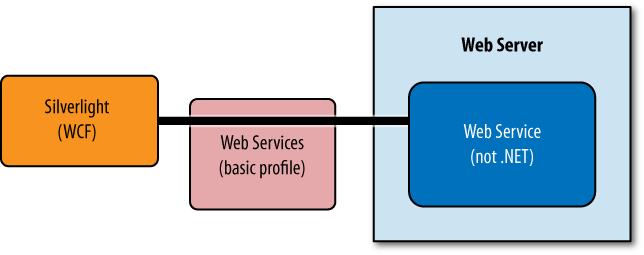

What if your server isn’t running .NET, but you still want to use .NET on the web client? There are some restrictions on WCF in this scenario. Silverlight’s version of WCF is much more limited than the version in the full .NET Framework—whereas the full version can be configured to use all manner of different protocols, Silverlight’s WCF supports just two options. There’s the so-called basic profile for web services, in which only a narrow set of features is available, and there’s a binary protocol unique to WCF, which offers the same narrow set of features but makes slightly more efficient use of network bandwidth than the XML-based basic profile. So if you want a Silverlight client to use WCF to communicate with a non-.NET web service, as Figure 13-2 illustrates, this will work only if your service supports the basic profile.

More generally, if the information your client code works with looks like a set of resources that might be identified with URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers; for instance, http://oreilly.com/) and accessed via HTTP you might want to stick with ordinary HTTP rather than using WCF. Not only do you get the benefits of normal HTTP caching when reading data, but it may also simplify security—you might be able to take whatever mechanism you use to log people into the website and secure access to web pages, and use it to secure the resources you fetch programmatically.

Note

A service that presents a set of resources identified by URIs to be accessed via standard HTTP mechanisms is sometimes described as a RESTful service. REST, short for Representational State Transfer, is an architectural style for distributed systems. More specifically, it’s the style used by the World Wide Web. The term comes from the PhD thesis of one of the authors of the HTTP specification (Roy Fielding). REST is a much misunderstood concept, and many people think that if they’re doing HTTP they must be doing REST, but it’s not quite that straightforward. It’s closer to the truth to say that REST means using HTTP in the spirit in which HTTP was meant to be used. For more information on the thinking behind REST, we recommend the book RESTful Web Services by Sam Ruby and Leonard Richardson, (O’Reilly).

Occasionally, neither WCF nor plain HTTP will be the best approach when connecting a web UI to a service. With Silverlight, you have the option to use TCP or UDP sockets from the web browser. (The UDP support is somewhat constrained. Silverlight 4, the current version at the time of writing this, only supports UDP for multicast client scenarios.) This is a lot more work, but it can support more flexible communication patterns—you’re not constrained to the request/response style offered by HTTP. Games and chat applications might need this flexibility, because it provides a way for the server to notify the client anytime something interesting happens. Sockets can also offer lower communication latency than HTTP, which can be important for games.

Fashionable though web applications are, they’re not the only kind of distributed system. Traditional Windows applications built with WPF or Windows Forms are still widely used, as they can offer some considerable advantages over web applications for both users and developers. Obviously, they’re an option only if all your end users are running Windows, but for many applications that’s a reasonable assumption. Assuming clients are running Windows, the main downside of this kind of application is that it’s hard to control deployment compared to a web application. With web applications, you only have to update an application on the server, and all your clients will be using the new version the next time they request a new page.

You won’t necessarily write the code at both ends of a connection. You might build a .NET client which talks to a web service provided by someone else. For example, you could write a WPF frontend to an online social media site such as Twitter, or a Silverlight client that accesses an external site such as Digg.

Note that because Silverlight’s version of WCF is considerably more limited than the full .NET Framework version, a Silverlight client is more likely to have to drop down to the HTTP APIs than a full .NET client.

If you are writing a web service in .NET that you would like to be accessible to client programs written by people other than you, the choice of technology will be determined by two things: the nature of the service and the demands of your clients.[26] If it’s something that fits very naturally with HTTP—for example, you are building a service for retrieving bitmaps—writing it as an ordinary ASP.NET application may be the best bet (in which case, refer to Chapter 21). But for services that feel more like a set of remotely invocable methods, WCF is likely to be the best bet. You can configure WCF to support a wide range of different network protocols even for a single service, thus supporting a wide range of clients.

As with the other application types, you would use sockets only if your application has unusual requirements that cannot easily be met using the communication patterns offered by HTTP.

So having looked at some common scenarios and seen which communication options are more or less likely to fit, let’s look at how to use those options.