C# 4.0 introduces a new type called dynamic. In some ways it

looks just like any other type such as int, string,

or FileStream: you can use it in

variable declarations, or function arguments and return types, as Example 18-4 shows. (The method reads a little oddly—it’s a

static method in the sense that it does

not relate to any particular object instance. But it’s dynamic in the

sense that it uses the dynamic type for

its parameters and return value.)

Example 18-4. Using dynamic

static dynamic AddAnything(dynamic a, dynamic b)

{

dynamic result = a + b;

Console.WriteLine(result);

return result;

}While you can use dynamic almost

anywhere you could use any other type name, it has some slightly unusual

characteristics, because when you use dynamic, you are really saying “I have no idea

what sort of thing this is.” That means there are some situations where

you can’t use it—you can’t derive a class from dynamic, for example, and typeof(dynamic) will not compile. But aside from

the places where it would be meaningless, you can use it as you’d use any

other type.

To see the dynamic behavior in action, we can try passing in a few

different things to the AddAnything method from

Example 18-4, as Example 18-5 shows.

Example 18-5. Passing different types

Console.WriteLine(AddAnything("Hello", "world").GetType().Name);

Console.WriteLine(AddAnything(31, 11).GetType().Name);

Console.WriteLine(AddAnything("31", 11).GetType().Name);

Console.WriteLine(AddAnything(31, 11.5).GetType().Name);AddAnything prints the value it

calculates, and Example 18-5 then goes on to

print the type of the returned value. This produces the following

output:

Helloworld String 42 Int32 3111 String 42.5 Double

The + operator in AddAnything has behaved differently

(dynamically, as it were) depending on the type of data we provided it

with. Given two strings, it appended them, producing a string result.

Given two integers, it added them, returning an integer as the result.

Given some text and a number, it converted the number to a string, and

then appended that to the first string. And given an integer and a double,

it converted the integer to a double and then added it to the other

double.

If we weren’t using dynamic,

every one of these would have required C# to generate quite different

code. If you use the + operator in a

situation where the compiler knows both types are strings, it generates

code that calls the String.Concat method. If

it knows both types are integers, it will instead generate code that

performs arithmetic addition. Given an integer and a double, it will

generate code that converts the integer to a double, followed by code to

perform arithmetic addition. In all of these cases, it would uses the

static information it has about the types to work out what code to

generate to represent the expression a +

b.

Clearly C# has done something quite different with Example 18-4. There’s only one method, meaning it had to

produce a single piece of code that is somehow able to execute any of

these different meanings for the +

operator. The compiler does this by generating code that builds a special

kind of object that represents an addition operation, and this object then

applies similar rules at runtime to those the compiler would have used at

compile time if it knew what the types were. (This makes dynamic very different from var—see the sidebar on the next page.)

So the behavior is consistent with what we’re used to with C#. The

+ operator continues to mean all the

same things it can normally mean, it just picks the specific meaning at

runtime—it decides dynamically. The +

operator is not the only language feature capable of dynamic operation. As

you’d expect, when using numeric types, all the mathematical operators

work. In fact, most of the language elements you can use in a normal C#

expression work as you’d expect. However, not all operations make sense in

all scenarios. For example, if you tried to add a COM object to a number,

you’d get an exception. (Specifically, a RuntimeBinderException, with a message

complaining that the + operator cannot

be applied to your chosen combination of types.) A COM object such as one

representing an Excel spreadsheet is a rather different sort of thing from

a .NET object. This raises a question: what sorts of objects can we use

with dynamic?

Not all objects behave in the same way when you use them

through the dynamic keyword. C#

distinguishes between three kinds of objects for dynamic purposes: COM

objects, objects that choose to customize their dynamic behavior, and

ordinary .NET objects. We’ll see several examples of that second

category, but we’ll start by looking at the most important dynamic

scenario: interop with COM objects.

COM objects such as those offered by Microsoft Word or Excel get

special handling from dynamic. It

looks for COM automation support (i.e., an implementation of the

IDispatch COM interface) and uses

this to access methods and properties. Automation is designed to

support runtime discovery of members, and it provides mechanisms for

dealing with optional arguments, coercing argument types where

necessary. The dynamic keyword

defers to these services for all member access. Example 18-6 relies on this.

Example 18-6. COM automation and dynamic

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Type appType = Type.GetTypeFromProgID("Word.Application");

dynamic wordApp = Activator.CreateInstance(appType);

dynamic doc = wordApp.Documents.Open("WordDoc.docx", ReadOnly:true);

dynamic docProperties = doc.BuiltInDocumentProperties;

string authorName = docProperties["Author"].Value;

doc.Close(SaveChanges:false);

Console.WriteLine(authorName);

}The first two lines in this method just create an instance of

Word’s application COM class. The line that calls wordApp.Documents.Open will end up using COM

automation to retrieve the Document

property from the application object, and then invoke the Open method on the document object. That

method has 16 arguments, but dynamic uses the mechanisms provided by COM

automation to offer only the two arguments the code has provided,

letting Word provide defaults for all the rest.

Although dynamic is doing

some very COM-specific work here, the syntax looks like normal C#.

That’s because the compiler has no idea what’s going on here—it never

does with dynamic. So the syntax

looks the same regardless of what happens at runtime.

If you are familiar with COM you will be aware that not all COM

objects support automation. COM also supports custom interfaces, which do not

support dynamic semantics—they rely on compile-time knowledge to work

at all. Since there is no general runtime mechanism for discovering

what members a custom interface offers, dynamic is unsuitable for dealing with these

kinds of COM interfaces. However, custom interfaces are well suited to

the COM interop services described in Chapter 19. dynamic was added to C# mainly because of

the problems specific to automation, so trying to use it with custom

COM interfaces would be a case of the wrong tool for the job. dynamic is most likely to be useful for

Windows applications that provide some sort of scripting feature

because these normally use COM automation, particularly those that

provide VBA as their default scripting language.

Silverlight applications can run in the web browser,

which adds an important interop scenario: interoperability between C#

code and browser objects. Those might be objects from the DOM, or from

script. In either case, these objects have characteristics that fit

much better with dynamic than with

normal C# syntax, because these objects decide which properties are

available at runtime.

Silverlight 3 used C# 3.0, so dynamic was not available. It was still

possible to use objects from the browser scripting world, but the

syntax was not quite as natural. For example, you might have defined a

JavaScript function on a web page, such as the one shown

in Example 18-7.

Example 18-7. JavaScript code on a web page

<script type="text/javascript">

function showMessage(msg)

{

var msgDiv = document.getElementById("messagePlaceholder");

msgDiv.innerText = msg;

}

</script>Before C# 4.0, you could invoke this in a couple of ways, both of which are illustrated in Example 18-8.

Example 18-8. Accessing JavaScript in C# 3.0

ScriptObject showMessage = (ScriptObject)

HtmlPage.Window.GetProperty("showMessage");

showMessage.InvokeSelf("Hello, world");

// Or...

ScriptObject window = HtmlPage.Window;

window.Invoke("showMessage", "Hello, world");While these techniques are significantly less horrid than the C#

3.0 code for COM automation, they are both a little cumbersome. We

have to use helper methods—GetProperty, InvokeSelf, or Invoke to retrieve properties and invoke

functions. But Silverlight 4 supports C# 4.0, and all script objects

can now be used through the dynamic keyword, as Example 18-9 shows.

Example 18-9. Accessing JavaScript in C# 4.0

dynamic window = HtmlPage.Window;

window.showMessage("Hello, world");This is a far more natural syntax, so much so that the second

line of code happens to be valid JavaScript as well as being valid C#.

(It’s idiomatically unusual—in a web page, the window object is the global object, and so

you’d normally leave it out, but you’re certainly allowed to refer to

it explicitly, so if you were to paste that last line into script in a

web page, it would do the same thing as it does in C#.) So dynamic has given us the ability to use

JavaScript objects in C# with a very similar syntax to what we’d use

in JavaScript itself—it doesn’t get much more straightforward than

that.

Note

The Visual Studio tools for Silverlight do not automatically

add a reference to the support library that enables dynamic to work. So when you first add a

dynamic variable to a Silverlight

application, you’ll get a compiler error. You need to add a

reference to the Microsoft.CSharp

library in your Silverlight project. This applies only to

Silverlight projects—other C# projects automatically have a

reference to this library.

Although the dynamic keyword was

added mainly to support interop scenarios, it is quite capable of

working with normal .NET objects. For example, if you define a class

in your project in the normal way, and create an instance of that

class, you can use it via a dynamic

variable. In this case, C# uses .NET’s reflection APIs to work out

which methods to invoke at runtime. We’ll explore this with a simple

class, defined in Example 18-10.

Example 18-10. A simple class

class MyType

{

public string Text { get; set; }

public int Number { get; set; }

public override string ToString()

{

return Text + ", " + Number;

}

public void SetBoth(string t, int n)

{

Text = t;

Number = n;

}

public static MyType operator + (MyType left, MyType right)

{

return new MyType

{

Text = left.Text + right.Text,

Number = left.Number + right.Number

};

}

}We can use objects of this through a dynamic variable, as Example 18-11 shows.

Example 18-11. Using a simple object with dynamic

dynamic a = new MyType { Text = "One", Number = 123 };

Console.WriteLine(a.Text);

Console.WriteLine(a.Number);

Console.WriteLine(a.Problem);The lines that call Console.WriteLine all use the dynamic

variable a with normal C# property

syntax. The first two do exactly what you’d expect if the variable had

been declared as MyType or var instead of dynamic: they just print out the values of

the Text and Number properties. The third one is more

interesting—it tries to use a property that does not exist. If the

variable had been declared as either MyType or var, this would not have compiled—the

compiler would have complained at our attempt to read a property that

it knows is not there. But because we’ve used dynamic, the compiler does not even attempt

to check this sort of thing at compile time. So it compiles, and

instead it fails at runtime—that third line throws a RuntimeBinderException, with a message

complaining that the target type does not define the Problem member we’re looking for.

This is one of the prices we pay for the flexibility of dynamic

behavior: the compiler is less vigilant. Certain programming errors

that would be caught at compile time when using the static style do

not get detected until runtime. And there’s a related price:

IntelliSense relies on the same compile-time type information that

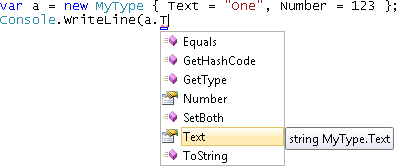

would have noticed this error. If we were to change the variable in Example 18-11’s type to either

MyType or var, we would see IntelliSense pop ups such

as those shown in Figure 18-1 while writing

the code.

Visual Studio is able to show the list of available methods

because the variable is statically typed—it will always refer to a

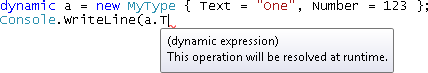

MyType object. But with dynamic, we get much less help. As Figure 18-2 shows, Visual

Studio simply tells us that it has no idea what’s available. In this

simple example, you could argue that it should be able to work it

out—although we’ve declared the

variable to be dynamic, it can only

ever be a MyType at this point in

the program. But Visual Studio does not attempt to perform this sort

of analysis for a couple of reasons. First, it would work for only

relatively trivial scenarios such as these, and would fail to work

anywhere you were truly exploiting the dynamic nature of dynamic—and if you don’t really need the

dynamism, why not just stick with statically typed variables? Second,

as we’ll see later, it’s possible for a type to customize its dynamic

behavior, so even if Visual Studio knows that a dynamic variable always refers to a MyType object, that doesn’t necessarily mean

that it knows what members will be available at runtime. Another

upshot is that with dynamic

variables, IntelliSense provides the rather less helpful pop up shown

in Figure 18-2.

Example 18-11 just reads the properties, but as you’d expect, we can set them, too. And we can also invoke methods with the usual syntax. Example 18-12 illustrates both features, and contains no surprises.

Example 18-12. Setting properties and calling methods with dynamic

dynamic a = new MyType();

a.Number = 42;

a.Text = "Foo";

Console.WriteLine(a);

dynamic b = new MyType();

b.SetBoth("Bar", 99);

Console.WriteLine(b);Our MyType example also

overloads the + operator—it defines

what should occur when we attempt to add two of these objects

together. This means we can take the two objects from Example 18-12 and pass them to

the AddAnything method

from Example 18-4, as Example 18-13 shows.

Recall that Example 18-4 just uses the

normal C# syntax for adding two things together. We wrote that code

before even writing the MyType

class, but despite this, it works just fine—it prints out:

FooBar, 141

The custom + operator in

MyType concatenates the Text properties and adds the Number properties, and

we can see that’s what’s happened here. Again, this shouldn’t really

come as a surprise—this is another example of the basic principle that

operations should work the same way when used through dynamic as they would statically.

Example 18-13 illustrates

another feature of dynamic—assignment. You can, of course,

assign any value into a variable of type dynamic, but what’s more surprising is that

you can also go the other way—you are free to assign an expression of

dynamic type into a variable of any

type. The first line of Example 18-13 assigns the return

value of AddAnything into a variable of type

MyType. Recall that AddAnything has a return type of dynamic, so you might have thought we’d need

to cast the result back to MyType

here, but we don’t. As with all dynamic operations, C# lets you try

whatever you want at compile time and then tries to do what you asked

at runtime. In this case, the assignment succeeds because AddAnything ended up adding two MyType objects together to return a

reference to a new MyType object.

Since you can always assign a reference to a MyType object into a MyType variable, the assignment succeeds. If

there’s a type mismatch, you get an exception at runtime. This is just

another example of the same basic principle; it’s just a bit subtler

because assignment is usually a trivial operation in C#, so it’s not

immediately obvious that it might fail at runtime.

While most operations are available dynamically, there are a

couple of exceptions. You cannot invoke methods declared with the

static keyword via dynamic. In some ways, this is

unfortunate—it could be useful to be able to select a particular

static (i.e., noninstance) method

dynamically, based on the type of object you have. But that would be

inconsistent with how C# works normally—you are not allowed to invoke

static methods through a statically

typed variable. You always need to call them via their defining type

(e.g., Console.WriteLine). The

dynamic keyword does not change

anything here.

Extension methods are also not available through

dynamic variables. On the one hand,

this makes sense because extension methods are really just static methods disguised behind a convenient

syntax. On the other hand, that convenient syntax is designed to make

it look like these are really instance methods, as Example 18-14 shows.

Example 18-14. Extension methods with statically typed variables

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

IEnumerable<int> numbers = Enumerable.Range(1, 10);

int total = numbers.Sum();

}

}The call to numbers.Sum() makes

it look like IEnumerable<int>

defines a method called Sum. In

fact there is no such method, so the compiler goes looking for

extension methods—it searches

all of the types in all of the namespaces for which we have provided

using directives. (That’s why we’ve

included the whole program here rather than just a snippet—you need

the whole context including the using

System.Linq; directive for that method call to make sense.)

And it finds that the Enumerable

type (in the System.Linq namespace)

offers a suitable Sum extension

method.

If we change the first line in the Main method to the code shown in Example 18-15, things go

wrong.

The code still compiles, but at runtime, when we reach the call

to Sum, it throws a RuntimeBinderException complaining that the

target object does not define a method called Sum.

So, in this case, C# has abandoned the usual rule of ensuring

that the runtime behavior with dynamic matches what statically typed

variables would have delivered. The reason is that the code C#

generates for a dynamic call does not contain enough context. To

resolve an extension method, it’s necessary to know which using directives are present. In theory, it

would have been possible to make this context available, but it would

significantly increase the amount of information the C# compiler would

need to embed—anytime you did

anything to a dynamic variable, the

compiler would need to ensure that a list of all the relevant

namespaces was available. And even that wouldn’t be sufficient—at

compile time, C# only searches for extension methods in the assemblies

your project references, so to deliver the same method resolution

semantics at runtime that you get statically would require that

information to be made available too.

Worse, this would prevent the C# compiler from being able to optimize your project references. Normally, C# detects when your project has a reference to an assembly that your code never uses, and it removes any such references at compile time.[50] But if your program made any dynamic method calls, it would need to keep references to apparently unused assemblies, just in case they turn out to be necessary to resolve an extension method call at runtime.

So while it would have been possible for Microsoft to make this

work, there would be a significant price to pay. And it would probably

have provided only marginal value, because it wouldn’t even be useful

for the most widely used extension methods. The biggest user of

extension methods in the .NET Framework class library is LINQ—that

Sum method is a standard LINQ

operator, for example. It’s one of the simpler ones. Most of the

operators take arguments, many of which expect lambdas. For those to

compile, the C# compiler depends on static type information to create

a suitable delegate. For example, there’s an overload of the Sum operator that takes a lambda, enabling you to compute the sum of a value

calculated from the underlying data, rather than merely summing the

underlying data itself. Example 18-16 uses this

overload to calculate the sum of the squares of the numbers in the

list.

When the numbers variable has

a static type (IEnumerable<int> in our case) this

works just fine. But if numbers is

dynamic, the compiler

simply doesn’t have enough information to know what code it needs to

generate for that lambda. Given sufficiently heroic efforts from the

compiler, it could embed enough information to be able to generate all

the necessary code at runtime, but for what benefit? LINQ is designed

for a statically typed world, and dynamic is designed mainly for interop. So

Microsoft decided not to support these kinds of scenarios with

dynamic—stick with static typing

when using LINQ.

The dynamic keyword uses an

underlying mechanism that is not unique to C#. It depends on a set of

libraries and conventions known as the DLR—the Dynamic Language

Runtime. The libraries are built into the .NET Framework, so these

services are available anywhere .NET 4 or later is available. This

enables C# to work with dynamic objects from other languages.

Earlier in this chapter, we mentioned that in the Ruby programming language, it’s possible to write code that decides at runtime what methods a particular object is going to offer. If you’re using an implementation of Ruby that uses the DLR (such as IronRuby), you can use these kinds of objects from C#. The DLR website provides open source implementations of two languages that use the DLR: IronPython and IronRuby (see http://dlr.codeplex.com/).

The .NET Framework class library includes a class called

ExpandoObject, which is designed to be used through dynamic variables. It chooses to customize

its dynamic behavior. (It does this by implementing a special

interface called IDynamicMetaObjectProvider. This is defined

by the DLR, and it’s also the way that objects from other languages

are able to make their language-specific dynamic behavior available to

C#.) If you’re familiar with JavaScript, the idea behind ExpandoObject will be familiar: you can set

properties without needing to declare them first, as Example 18-17 shows.

Example 18-17. Setting dynamic properties

dynamic dx = new ExpandoObject(); dx.MyProperty = true; dx.AnotherProperty = 42;

If you set a property that the ExpandoObject didn’t previously have, it

just grows that as a new property, and you can retrieve the property

later on. This behavior is conceptually equivalent to a Dictionary<string, object>, the only

difference being that you get and set values in the dictionary using

C# property accessor syntax, rather than an indexer. You can even

iterate over the values in an ExpandoObject just as you would with a

dictionary, as Example 18-18

shows.

Example 18-18. Iterating through dynamic properties

foreach (KeyValuePair<string, object> prop in dx)

{

Console.WriteLine(prop.Key + ": " + prop.Value);

}If you are writing C# code that needs to interoperate with

another language that uses the DLR, this class can be

convenient—languages that fully embrace the dynamic style often use

this sort of dynamically populated object in places where a more

statically inclined language would normally use a dictionary, so

ExpandoObject can provide a

convenient way to bridge the gap. ExpandoObject implements IDictionary<string, object>, so it

speaks both languages. As Example 18-19 shows, you add

properties to an ExpandoObject

through its dictionary API and then go on to access those as dynamic

properties.

Example 18-19. ExpandoObject as both dictionary and dynamic object

ExpandoObject xo = new ExpandoObject(); IDictionary<string, object> dictionary = xo; dictionary["Foo"] = "Bar"; dynamic dyn = xo; Console.WriteLine(dyn.Foo);

This trick of implementing custom dynamic behavior is not unique

to ExpandoObject—we are free to write

our own objects that do the same thing.

The DLR defines an interface called IDynamicMetaObjectProvider, and objects that

implement this get to define how they behave when used dynamically. It

is designed to enable high performance with maximum flexibility, which

is great for anyone using your type, but it’s a lot of work to

implement. Describing how to implement this interface would require a

fairly deep discussion of the workings of the DLR, and is beyond the

scope of this book. Fortunately, a more straightforward option

exists.

The System.Dynamic namespace

defines a class called DynamicObject. This implements IDynamicMetaObjectProvider for you, and all

you need to do is override methods representing whichever operations

you want your dynamic object to support. If you want to support

dynamic properties, but you don’t care about any other dynamic

features, the only thing you need to do is override a single method,

TryGetMember, as Example 18-20 shows.

Example 18-20. Custom dynamic object

using System;

using System.Dynamic;

public class CustomDynamic : DynamicObject

{

private static DateTime FirstSighting = new DateTime(1947, 3, 13);

public override bool TryGetMember(GetMemberBinder binder,

out object result)

{

var compare = binder.IgnoreCase ?

StringComparer.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase :

StringComparer.InvariantCulture;

if (compare.Compare(binder.Name, "Brigadoon") == 0)

{

// Brigadoon famous for appearing only once every hundred years.

DateTime today = DateTime.Now.Date;

if (today.DayOfYear == FirstSighting.DayOfYear)

{

// Right day, what about the year?

int yearsSinceFirstSighting = today.Year - FirstSighting.Year;

if (yearsSinceFirstSighting % 100 == 0)

{

result = "Welcome to Brigadoon. Please drive carefully.";

return true;

}

}

}

return base.TryGetMember(binder, out result);

}

}This object chooses to define just a single property, called

Brigadoon.[51] Our TryGetMember will be called anytime

some code attempts to read a property from our object. The GetMemberBinder argument provides the name

of the property the caller is looking for, so we compare it against

our one and only supported property name. The binder also tells us

whether the caller prefers a case-sensitive comparison—in C# IgnoreCase will be false, but some languages (such as VB.NET)

prefer case-insensitive comparisons. If the name matches, we then

decide at runtime whether the property should be present or not—this

particular property is available for only a day at a time once every

100 years. This may not be hugely useful, but it illustrates that

objects may choose whatever rules they like for deciding what

properties to offer.

Note

If you’re wondering what you would get in exchange for the

additional complexity of IDynamicMetaObjectProvider, it makes it

possible to use caching and runtime code generation techniques to

provide high-performance

dynamic operation. This is a lot more complicated than the simple

model offered by DynamicObject,

but has a significant impact on the performance of languages in

which the dynamic model is the norm.

[50] This optimization doesn’t occur for Silverlight projects, by the way. The way Silverlight uses control libraries from Xaml means Visual Studio has to be conservative about project references.

[51] According to popular legend, Brigadoon is a Scottish village which appears for only one day every 100 years.