Until now, you’ve seen no code using C/C++-style pointers. Pointers are central to the C family of languages, but in C#, pointers are relegated to unusual and advanced programming; typically, they are used only with P/Invoke, and occasionally with COM. C# supports the usual C pointer operators, listed in Table 19-1.

In theory, you can use pointers anywhere in C#, but in practice,

they are almost never required outside of interop scenarios, and their use

is nearly always discouraged. When you do use pointers, you must mark your

code with the C# unsafe modifier. The

code is marked as unsafe because pointers let you manipulate memory

locations directly, defeating the usual type safety rules. In unsafe code,

you can directly access memory, perform conversions between pointers and

integral types, take the address of variables, perform pointer arithmetic,

and so forth. In exchange, you give up garbage collection and protection

against uninitialized variables, dangling pointers, and accessing memory

beyond the bounds of an array. In essence, the unsafe keyword creates an

island of code within your otherwise safe C# application that is subject

to all the pointer-related bugs C++ programs tend to suffer from.

Moreover, your code will not work in partial-trust scenarios.

Note

Silverlight does not support unsafe code at all, because it only supports partial trust. Silverlight code running in a web browser is always constrained, because code downloaded from the Internet is not typically considered trustworthy. Even Silverlight code that runs out of the browser is constrained—the “elevated” permissions such code can request still don’t grant full trust. Silverlight depends on the type safety rules to enforce security, which is why unsafe code is not allowed.

As an example of when this might be useful, read a file to the

console by invoking two Win32 API calls: CreateFile and ReadFile. ReadFile takes, as its second parameter, a

pointer to a buffer. The declaration of the two imported methods is

straightforward:

[DllImport("kernel32", SetLastError=true)]

static extern unsafe int CreateFile(

string filename,

uint desiredAccess,

uint shareMode,

uint attributes,

uint creationDisposition,

uint flagsAndAttributes,

uint templateFile);

[DllImport("kernel32", SetLastError=true)]

static extern unsafe bool ReadFile(

int hFile,

void* lpBuffer,

int nBytesToRead,

int* nBytesRead,

int overlapped);You will create a new class, APIFileReader, whose constructor will invoke the

CreateFile()

method. The constructor takes a filename as a parameter, and passes that

filename to the CreateFile()

method:

public APIFileReader(string filename)

{

fileHandle = CreateFile(

filename, // filename

GenericRead, // desiredAccess

UseDefault, // shareMode

UseDefault, // attributes

OpenExisting, // creationDisposition

UseDefault, // flagsAndAttributes

UseDefault); // templateFile

}The APIFileReader class

implements only one other method, Read(), which invokes

ReadFile(). It passes in the file

handle created in the class constructor, along with a pointer into a

buffer, a count of bytes to retrieve, and a reference to a variable that

will hold the number of bytes read. It is the pointer to the buffer that

is of interest to us here. To invoke this API call, you must use a

pointer.

Because you will access it with a pointer, the buffer needs to be

pinned in memory; we’ve given ReadFile a pointer to our buffer, so we can’t

allow the .NET Framework to move that buffer during garbage collection

until ReadFile is finished. (Normally,

the garbage collector is forever moving items around to make more

efficient use of memory.) To accomplish this, we use the C# fixed keyword. fixed allows you to get a pointer to the memory

used by the buffer, and to mark that instance so that the garbage

collector won’t move it.

Warning

Pinning reduces the efficiency of the garbage collector. If an interop scenario forces you to use pointers, you should try to minimize the duration for which you need to keep anything pinned. This is another reason to avoid using pointers for anything other than places where you have no choice.

The block of statements following the fixed keyword creates a scope, within which the

memory will be pinned. At the end of the fixed block, the instance will be unpinned, and

the garbage collector will once again be free to move it. This is known as

declarative pinning:

public unsafe int Read(byte[] buffer, int index, int count)

{

int bytesRead = 0;

fixed (byte* bytePointer = buffer)

{

ReadFile(

fileHandle,

bytePointer + index,

count,

&bytesRead, 0);

}

return bytesRead;

}You may be wondering why we didn’t also need to pin bytesRead—the ReadFile method expects a pointer to that too.

It was unnecessary because bytesRead

lives on the stack here, not the heap, and so the garbage collector would

never attempt to move it. C# knows this, so it lets us use the & operator to get the address without having

to use fixed. If we had applied that

operator to an int that was stored as a

field in an object, it would have refused to compile, telling us that we

need to use fixed.

Warning

You need to make absolutely sure that you don’t unpin the memory

too early. Some APIs will keep hold of pointers you give them,

continuing to use them even after returning. For example, the ReadFileEx Win32 API can be used

asynchronously—you can ask it to return before it has fetched the data.

In that case you would need to keep the buffer pinned until the

operation completes, rather than merely keeping it pinned for the

duration of the method call.

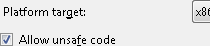

Notice that the method must be marked with the unsafe keyword. This

creates an unsafe context which allows you to create pointers—the compiler

will not let you use pointers or fixed

without this. In fact, it’s so keen to discourage the use of unsafe code

that you have to ask twice: the unsafe

keyword produces compiler errors unless you also set the /unsafe compiler option. In Visual Studio, you

can find this by opening the project properties and clicking the Build

tab, which contains the “Allow unsafe code” checkbox shown in Figure 19-7.

The test program in Example 19-3 instantiates the

APIFileReader and an ASCIIEncoding object. It passes the filename

(8Swnn10.txt) to the constructor of

the APIFileReader and then creates a

loop to repeatedly fill its buffer by calling the Read() method, which invokes the ReadFile API call. An array of bytes is

returned, which is converted to a string using the ASCIIEncoding object’s GetString() method. That

string is passed to the Console.Write() method,

to be displayed on the console. (As with the MoveFile example, this is obviously a

scenario where in practice, you’d just use the relevant managed APIs

provided by the .NET Framework in the System.IO namespace. This example just

illustrates the programming techniques for pointers.)

Note

The text that it will read is a short excerpt of Swann’s Way (by Marcel Proust), currently in the public domain and available for download as text from Project Gutenberg.

Example 19-3. Using pointers in a C# program

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using System.Text;

namespace UsingPointers

{

class APIFileReader

{

const uint GenericRead = 0x80000000;

const uint OpenExisting = 3;

const uint UseDefault = 0;

int fileHandle;

[DllImport("kernel32", SetLastError = true)]

static extern unsafe int CreateFile(

string filename,

uint desiredAccess,

uint shareMode,

uint attributes,

uint creationDisposition,

uint flagsAndAttributes,

uint templateFile);

[DllImport("kernel32", SetLastError = true)]

static extern unsafe bool ReadFile(

int hFile,

void* lpBuffer,

int nBytesToRead,

int* nBytesRead,

int overlapped);

// constructor opens an existing file

// and sets the file handle member

public APIFileReader(string filename)

{

fileHandle = CreateFile(

filename, // filename

GenericRead, // desiredAccess

UseDefault, // shareMode

UseDefault, // attributes

OpenExisting, // creationDisposition

UseDefault, // flagsAndAttributes

UseDefault); // templateFile

}

public unsafe int Read(byte[] buffer, int index, int count)

{

int bytesRead = 0;

fixed (byte* bytePointer = buffer)

{

ReadFile(

fileHandle, // hfile

bytePointer + index, // lpBuffer

count, // nBytesToRead

&bytesRead, // nBytesRead

0); // overlapped

}

return bytesRead;

}

}

class Test

{

public static void Main()

{

// create an instance of the APIFileReader,

// pass in the name of an existing file

APIFileReader fileReader = new APIFileReader("8Swnn10.txt");

// create a buffer and an ASCII coder

const int BuffSize = 128;

byte[] buffer = new byte[BuffSize];

ASCIIEncoding asciiEncoder = new ASCIIEncoding();

// read the file into the buffer and display to console

while (fileReader.Read(buffer, 0, BuffSize) != 0)

{

Console.Write("{0}", asciiEncoder.GetString(buffer));

}

}

}

}The key section of code where you create a pointer to the buffer and

fix that buffer in memory using the fixed keyword is shown in

bold.

This produces more than a page full of output, so we’ve truncated it here, but it begins:

Altogether, my aunt used to treat him with scant ceremony. Since she was of the opinion that he ought to feel flattered by our invitations, she thought it only right and proper that he should never come to see us in summer without a basket of peaches or raspberries from his garden, and that from each of his visits to Italy he should bring back some photographs of old masters for me. ...