Malt Whisky

Stages of Malt Whisky Production

1. Harvesting |

2. Malting |

3. Kilning |

4. Milling |

5. Mashing |

6. Fermenting |

7. Distilling |

8. Maturing |

9. Bottling |

10. Drinking |

Find out more about each production stage in the following entries: |

|

39. How Is Malt Whisky Made?

Water, barley, yeast, and energy are the four things needed to make malt whisky. That sounds simple. But the process itself is much more complicated and can be further divided into the following steps: malting, kilning, milling, mashing, fermenting, distilling, maturing, and bottling.

40. Where Does the Water Come From?

Water is used at every step in the process of making whisky—and lots of it. This is one of the main reasons why most distilleries are located in the vicinity of a significant water source like a river or a spring and usually own their own springs. The water drawn from a spring and used for the actual whisky making is called “process water.” The water used in the condensers does not come into direct contact with the distillate and is called “cooling water.” It is normally drawn from a river nearby but can also be taken from the nearest municipality’s drinking-water source.

41. Does the Type of Water Used Affect the Whisky?

Water has an important influence on the whisky produced. It starts with the source and the condition of the soil. Water that streams over relatively soft soil, such as sand or limestone, absorbs more minerals than water flowing over hard, rocky terrain. Each type of soil contains different minerals. For example, the granite soil found in parts of Scotland’s Speyside is very hard and doesn’t contain many minerals, resulting in water that is pure and soft. In the Northern Highlands around Tain, though, the water is hard because it rises up to the surface through limestone, which is a sedimentary rock largely composed of calcium carbonate. On the Isle of Islay, the water flows over peaty soil, which contains decayed seaweed and sphagnum (a type of moss) that release phenols. Phenols are the compounds responsible for the smoky taste of some whiskies (see entries 46 and 47). However, it is unlikely that phenols in water are noticeable in the final whisky. The mineral content of water only influences the fermentation stage. When bottled, whisky is diluted with demineralized water, which doesn’t affect the flavor of the end product.

42. What Types of Grains Are Used?

Barley is the grain with the most flavor, and improving barley strains is a continuous effort, both for the farmer and the distiller. The former is interested in as large a harvest per square meter as possible; the latter in the highest possible yield of alcohol from a ton of barley. Cultivating new varieties is an ongoing process, especially because barley is very vulnerable to fungi—even strains that were previously resistant. Well-known barley strains are Golden Promise, Minstrel, Concerto, and Optimum.

“There are two things a Highlander likes naked, and the other one is malt whisky.”

Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart

43. Where Does the Barley Come From?

Barley may be sourced anywhere; it is not necessarily from the country where the whisky is distilled.

The general consensus is that the type of barley and its pedigree hardly influence the end product. Scotch, after all, doesn’t have to be distilled from Scottish barley. The majority of the barley used for Scotch is imported from England, Canada, Europe, or Australia. Price is usually the main factor when deciding where to get the grain. However, the suppliers have to follow the distilleries’ specifications to a T when delivering the barley, which can be as specific as the expected yield of alcohol per ton of barley. Some distilleries, like Bruichladdich, Benromach, and The Macallan, are particular about the pedigree of their barley and source it locally. The barley has to be malted before it can be used, which takes about a week. During this time, barley, now called “green malt,” becomes saturated with natural sugars, which will produce alcohol later in the distillation process.

44. What Is Malting?

Germinating barley on the edge of a steeping tank—the vessel used to soak the barley prior to spreading it on the malting floor.

Before it can be used, barley has to be malted—steeped in large steel water vessels for two to three days. During this time the grain becomes soft and sticky and starts to germinate. Small sprouts grow from the kernels, enzymes are released, and the starch in the grain is converted into maltose (a kind of sugar). Next, the grains are spread out on the malting floor to germinate; they’re turned regularly to prevent overheating. A handful of distilleries still turn the germinating malt manually by using a wooden spade (shiel) or a motorized device resembling a small lawn mower. Germination takes about a week, during which the “green malt” becomes saturated with natural sugars that will produce alcohol during distillation. Because this traditional process is quite labor intensive, nowadays it is largely mechanized and centralized. The majority of the barley comes from large commercial malting plants in Scotland that use centrifuges for the malting process.

45. What Is Kilning?

Left: The industrial drum malting plant at Port Ellen on Islay. Right: At Bowmore, the turning of the malt is still partly done by hand.

To stop germination, the barley needs to be dried. That happens in a drying oven, or kiln, using hot air. The chimney of many Scottish kilns has a pagoda-shaped fan, an innovation of architect Charles Doig in the nineteenth century. Now most distilleries buy their malted barley from large commercial maltings that produce their malt according to precise specifications. However, the pagodas on former kilns can be seen throughout Scotland.

46. How Does Peat Smoke Affect the Malted Barley?

Left: The old kiln of Aberfeldy, with its distinctive pagoda-shaped chimney. Right: A peat fire in the kiln at Highland Park, Orkney.

When peat is used to fuel the fire in the kiln, the whisky will have a distinctive smoky flavor. A distiller can specify the exact peat level to be used while drying, to make sure his whisky flavor is consistent. One can purchase stocks of malted barley with varying peat levels, which allow the distiller to produce different expressions from the same stills, ranging from a non-peated to a heavily peated whisky. So the smoky note in a whisky doesn’t come from water that contains peat but from burning peat in the kiln during the malting process.

The desired peat level is noted in the malt specification, expressed in parts per million (ppm) phenol. Phenols are organic compounds found in peat smoke and in barley. They are aromatic substances similar to alcohol. Phenol used to be called carbolic acid. There are nine different phenols in peat smoke, each carrying a specific aroma. The source of the peat is important too. For example, Highland Park (from the Orkneys in Scotland) has a distinctly different peaty character than Lagavulin (made on the Isle of Islay).

48. Why Is the Malted Barley Milled?

The malt mill at Tobermory, Isle of Mull.

Once at the distillery, the malt is strained through a large sieve to remove stones or debris and then transported to a mill that grinds it into a coarse flour called grist. This is essential for the next step: mashing.

49. What Is Mashing?

Mash tuns are usually closed vessels, like this one at Ardmore.

Mashing is mixing grist with warm water in a huge vessel called the mash tun. This results in a thick “porridge” that is stirred constantly by a giant mechanical mixer. The maltose in the grist dissolves in the water and the remaining sweet liquid, called wort, is drained out of the mash tun. After cooling, the wort is ready for fermentation.

50. What Is a Mash Tun?

A mash tun is a brewing vessel made of cast iron or stainless steel wherein the grist is mixed with warm water. The bottom is a sieve that can be opened and closed. Once it is opened, the liquid can flow into the underback, while the solids stay in the mash tun (see entry 53).

51. What Is an Underback?

The container that catches the wort when the sieve in the mash tun is opened is called the underback. It catches the liquid before it is pumped to a washback (see entry 54).

52. What Is the Influence of Water During Mashing?

Mashing takes lots of water. It is done in two or three cycles, depending on the preferences of the distiller; the water temperature may differ at each cycle. The quality of the water and the substances found in it are very important during this phase. Too many minerals, like copper or iron, could cause problems during fermentation, which is the next step in the process. The acidity of the water is also important and affects the forming of esters (chemical compounds) during fermentation.

Draff is the residue left in the mash tun; it’s later used as cattle feed. Distilling whisky is, in a way, based on the cradle-to-cradle principle: the draff returns to the food chain, serving as food for cows, and their manure enriches the soil where barley is grown.

In Deanston’s open mash tun, the mixer stirring the mash is clearly visible.

A washback is a fermentation vessel made of wood or stainless steel. All washbacks used to be made of wood—predominantly Oregon pine, Douglas fir, or Siberian larch—which required them to be replaced after fifty to sixty years of daily use. Many distilleries have switched to stainless steel because it’s more economical, requires less maintenance, and is easier to clean.

55. Stainless Steel Versus Wooden Washbacks

Left: Wooden washbacks at Glenrothes. Right: Stainless steel washbacks at Tomatin.

Those distillers that made the switch from wooden washbacks to stainless steel ones will mostly claim that it does not affect the taste of the whisky. Those who still use traditional wooden washbacks emphasize that it does. Washbacks are cleaned after each cycle with high-pressure steam and hot water, and there is a realistic chance that some microorganisms are left on the wooden washbacks. This surely adds to the taste of the end product.

56. What Is Fermentation?

Foaming wash in a washback at Aberfeldy.

Fermentation, occasionally referred to as yeasting, is nothing more than changing the chemical structure of a liquid with the use of microorganisms. Yeast is a single-cell fungus that feeds on oxygen and multiplies at a fast rate. This is called aerobic fermentation. Yeast is also capable of converting sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, which is called anaerobic fermentation. The anaerobic reaction between yeast and glucose is expressed with the following formula: C6H12O6 (glucose) → 2C2H5OH (ethanol) + 2CO2. This is the fermentation process that makes whisky. When yeast is added to the wort in the washback, the liquid starts foaming and frothing aggressively and sugars are converted into carbon dioxide and alcohol. A chemical reaction is set off with the acids in the malt, which creates esters and aldehydes. We perceive them as different aromas of fruits and flowers.

57. How Does the Yeast Influence the Flavor?

Yeast itself does not contribute any flavors or aromas to the finished product. Flavor is created during fermentation. The aromas we associate with flowers and fruit come from a combination of many different esters. For example, n-pentyl acetate has a distinctive aroma of bananas.

58. What Kinds of Yeast Are Used in Fermentation?

Early on, fermentation used to be spontaneous, when free-roaming fungi in nature and on people, animals, and plants could trigger the process. However, dedicated yeast strains were developed for bakers, brewers, and distillers over time. At first, all three types were used in the whisky industry, but gradually the switch was made to only distiller’s yeast, which can be used in solid or liquid form. The most commonly used distiller’s yeast brands are Mauri, Quest, and Kerry. Some craft distillers may still use brewer’s yeast or baker’s yeast.

59. Where Do the Distilleries Get Their Yeast?

Most world distilleries buy their yeast from a specialized production plant, with the exception of American distilleries, where yeast strains are usually kept alive on the distillery grounds. It is not uncommon for an American distiller to use various yeast strains to make one whiskey. Four Roses straight bourbon is a good example—no less than five yeast strains are used in its production. However, most distilleries worldwide use one yeast strain.

60. How Long Does Fermentation Take?

The fermentation process differs from distillery to distillery. A minimum of forty-eight hours is a regular cycle, but sixty to seventy hours is not uncommon. A few distillers will even allow a hundred-hour fermentation cycle. The length of fermentation affects the flavors and aromas of the drink, as more esters develop over time. However, allowing fermentation to go on for too long may cause bacteria to form, which can lead to undesired flavors and aromas like butyric acid. The remaining liquid at the end of fermentation is called “wash.”

61. What Is the Wash?

The wash is a product of fermentation in a washback. It is a liquid resembling heavy beer, with an ABV (see entry 204) of between 7 and 9 percent, which gets pumped into a pot still ready for distilling.

62. What Is a Wash Still?

A wash still, used during the first round of distillation, gets filled with the wash from the washback and heated. A window on the neck of the still allows the distiller to monitor how rapidly the still is heated. The distillate coming from the wash still is called “low wines.”

63. What Is a Pot Still?

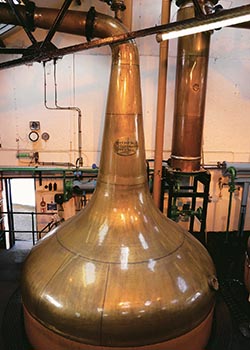

An onion-shaped pot still at Bowmore Distillery.

A pot still is a hefty copper kettle used to distill the wash. Historically, each distillery has its own still shapes, and the shape influences the flavor. There are three basic shapes of pot stills: the onion, the lantern, and the pear.

64. How Does a Pot Still Work?

A lantern-shaped pot still at Jura Distillery; a pear-shaped pot still at Lagavulin Distillery.

The still with the wash—alcoholic liquid resembling beer—is heated directly or indirectly. The boiling point of alcohol is lower than that of water, and the alcohol fumes rise up the neck of the still and enter a condenser (either a worm tub or a shell and tube; see what is a condenser). The fumes condense into an oily fluid containing approximately 22 percent ABV. This liquid is pumped to a second, smaller vessel, called the spirit still, where the process is repeated a second time while the condensed alcoholic liquid is separated into foreshots (heads), middle cut, and feints (tails). Only the liquid from the middle cut is suitable for making whisky.

65. What Is a Spirit Still?

A spirit still is used during the second round of distillation, in which the ABV is increased again. It is filled with the distillate (low wines) from the wash still. When heated and condensed, the liquid passes through a spirit safe, where foreshots, middle cut, and feints are separated.

66. What Is a Purifier?

A purifier is connected to the still to promote reflux (see entry 70).

67. What Is a Lyne Arm?

The lyne arm, sometimes called a lye pipe, is the part of the still that connects the neck with the condenser. The angle at which it is connected, which can vary from a perfect 90 degrees to ascending or descending, will influence the distillate.

68. What Is a Swan Neck?

The swan neck connects the base of the still to the lyne arm, and the longer it is, the lighter the distillate will be. The stills at Glenmorangie, for example, have extremely long necks and are nicknamed “the giraffes” in the industry. In contrast, The Macallan has small, squat stills with short necks, resulting in a heavier distillate with a similar body. This is no indication of the qualities of these whiskies but points to a certain style.

69. What Is a Boil Ball?

A boil ball is a round widening between the base of the still and its neck. It promotes reflux (see entry 70).

Parts of the still: 1. purifier; 2. lyne arm; 3. swan neck; 4. boil ball.

Reflux is a process whereby certain alcohol fumes condense in the still before reaching the condenser. They return to liquid form, fall back into the still, and are redistilled. Reflux promotes a delicate distillate.

71. Why Do Pot Still Shapes Differ?

Over time, each distillery has established its own preference regarding still shape based on the type and amount of spirit it produces. When a still has to be replaced, the coppersmith will create a new one with the exact same shape. A change in shape means a change in flavor.

72. Why Are Pot Stills Made of Copper?

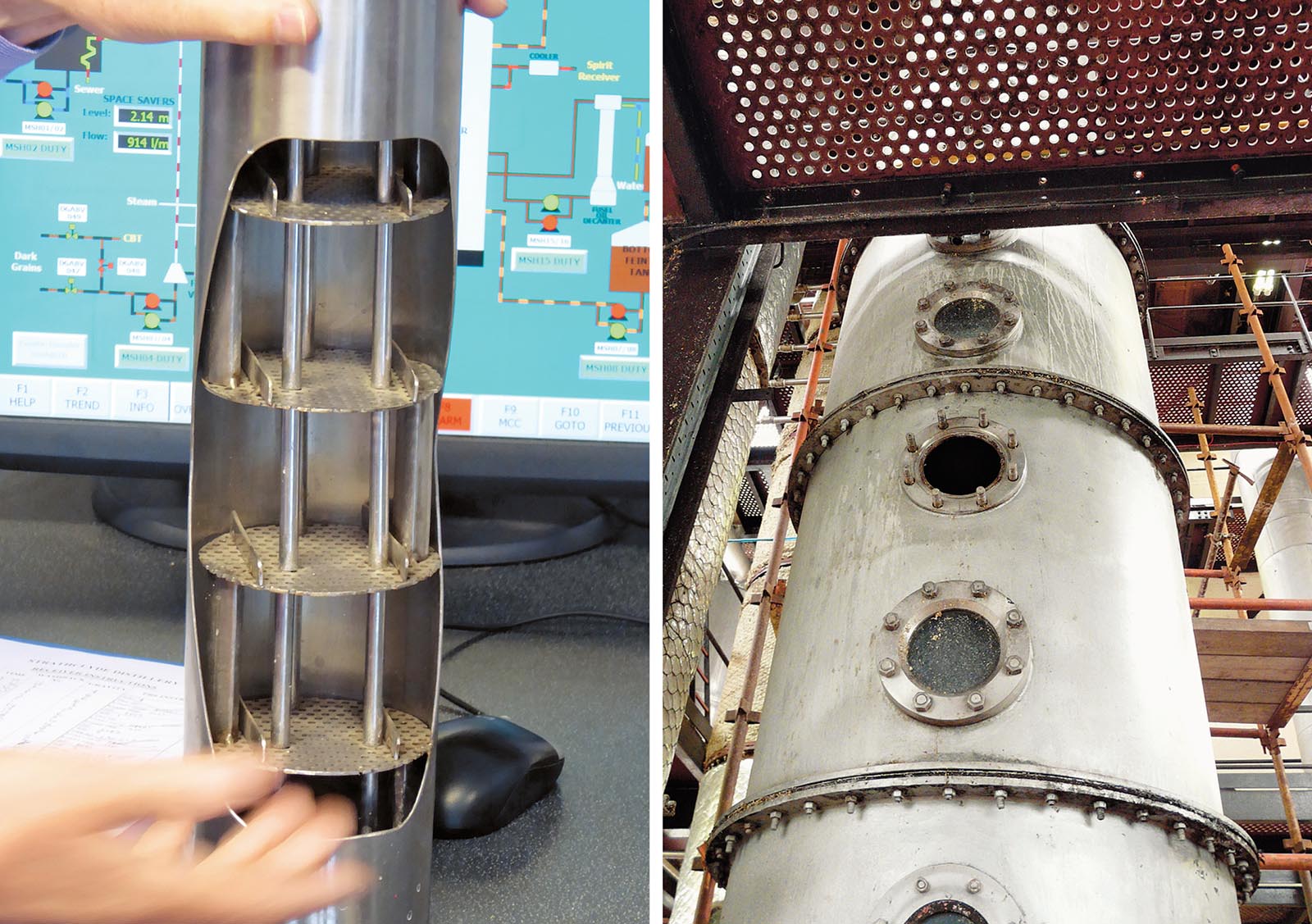

Scale models of Glenmorangie’s and The Macallan’s pot stills.

Copper has a few important characteristics. First of all, it is easy to mold into a desired shape. Second, copper acts as a catalyst in the process and removes undesired elements, like sulfur compounds, from the distillate. Third, copper is an excellent heat conductor.

A condenser cools the alcohol fumes that rise from the still. There are two different types in use today. The first one is called a worm tub, a large vessel made of wood or steel, with a copper spiral tube immersed in cold water. The fumes travel down through the spiral and condense into liquid. The worm tub is an older piece of equipment—many distilleries have switched to the other type, the shell and tube condenser, which works the opposite way. The fumes rise through a column where small copper pipes are filled with cold water. Both condensers perform the same job, but the type of condensation does influence the body and taste of the eventual whisky.

Shell and tube condensers at Tobermory, on the Isle of Mull.

74. What Is Direct Heating?

Most pot stills used to be heated over an open fire. However, health-and-safety regulations banned open fires, and a switch has been made to external heating below the still. This is called direct heating. If caramelization occurs on the bottom of the still, which sometimes happens, the residue is removed by a rummager.

75. What Is a Rummager?

A rummager is a chain used for scraping away the residue on the bottom of the still.

76. What Is Indirect Heating?

Pot stills can also be heated indirectly, by means of steam coils or steam pans placed inside the lower part of the still. This type of heating prevents caramelization and, more important, makes it easier to monitor and regulate the distilling temperature.

The spirit safe at Bowmore.

The spirit safe separates the foreshots, middle cut, and feints (see entries 78–80) during the second round of distillation. In some distilleries this process is automated, in others it is still done by hand. The distiller is most interested in the middle cut, which will be used for maturation. Using a thermometer and a hydrometer, he measures the temperature and relative density of the distillate and decides when to turn the handle.

78. What Are Foreshots?

Foreshots are highly volatile alcohols, some of which are not suitable for consumption, like methanol. They are separated during the second round of distillation in the spirit safe and redistilled in a subsequent round.

79. What Is the Middle Cut?

The middle cut, a liquid containing somewhere between 60 and 70 percent ABV, is also referred to as “the heart of the run.” It is transferred into a vessel called the spirit receiver, and the liquid is pumped to the filling store, where it is poured into oak casks.

80. What Are Feints?

Feints are heavy alcohols and fusel oils. Some may negatively influence the taste of the eventual whisky. Therefore, they are separated and redistilled in a subsequent round in the spirit still.

81. What Is a Feints Receiver?

This is a large container that catches the feints (tails or aftershots) before they are redistilled with the next batch.

82. What Is a Low Wines Receiver?

A low wines receiver is a container that collects the distillate from the wash still before it’s pumped into the spirit still.

83. What Is New Make Spirit?

New make spirit is the newly distilled spirit ready for maturation in casks. It is a colorless liquid containing between 63.5 and 70 percent ABV. An old-fashioned name for it is “clearic.”

84. What Is a Spirit Receiver?

The spirit receiver is the vessel that contains the new make spirit before it is pumped to the filling store.

85. What Is Pot Ale?

The residue in the wash still after distillation is called the pot ale. It is rich in proteins and used for feeding cattle, as fertilizer, and as fuel to generate energy.

86. What Are Spent Lees?

The residue in the spirit still after distillation is called the spent lees. It will be filtered in an effluent plant and discarded, usually in a nearby river, since it can’t be used further.

87. What Is Triple Distillation?

The trio of pot stills at Auchentoshan, located west of the city of Glasgow.

The majority of malt whiskies are distilled twice, with the exception of a few, like Auchentoshan. This Lowlander is typically distilled three times, consecutively in a wash still, an intermediate still, and a spirit still. The result is a softer, gentler distillate. Hazelburn from Springbank in Campbeltown is also a triple-distilled single malt. In Ireland, triple distillation is more widespread.

88. How Does Spirit Get into a Cask?

The filling of the casks (or barrels) happens in the filling store. Most malt whisky is diluted with demineralized water to 63.5 percent ABV before it goes into the cask.

89. How Long Does Whisky Mature?

Scotch, by law, has to mature a minimum of three years in a bonded warehouse. The liquid cannot be considered whisky until the three-year mark and is instead called new make spirit or simply spirit until then. Many other countries follow the three-year rule, regardless of whether it is imposed by law. In the United States and Canada, different rules apply.

90. What Is a Dunnage Warehouse?

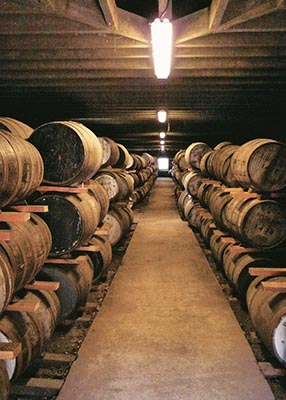

Casks with maturing whisky in the dunnage warehouses at Balblair.

An old traditional warehouse that is usually one or two stories tall, with thick stone walls and an earthen floor, is called a dunnage warehouse. Each floor can hold up to three stacked casks of spirit. Only a few distilleries continue to use this type of warehouse, the main reason being that it is less efficient in terms of storage and space. Some beautiful examples of this style of storage can be seen at Glenfarclas in Speyside and Balblair in the Northern Highlands.

Balblair Distillery.

91. What Is a Racked Warehouse?

In racked warehouses, casks are stacked horizontally in racks.

This modern type of warehouse contains huge racks where casks can be stacked fifteen to twenty high per row. Often the casks are palletized in an upright position, which helps the warehouse workers easily move them. The majority of distilleries have stopped maturing their whisky in the traditional dunnage warehouses at the distillery. Instead the casks are transported to a racked warehouse in the vicinity of a central bottling plant. Most whisky in Scotland is stored in huge warehouses in the “belt” between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Casks are palletized and stored vertically as well, predominantly in Ireland.

92. Does Whisky Always Mature in Wooden Casks?

Whisky has to mature in wooden casks, otherwise the bottled spirit isn’t whisky. Most countries specify oak as the only permitted wood for casks. The character of the wood has a huge influence on the eventual taste of the whisky.

93. What Types of Oak Are Used?

The Scottish whisky industry predominantly uses American and European oak, specifically the Quercus alba (white oak), Quercus robur (summer oak), and Quercus petraea (winter oak) species. In recent years, other species have been experimented with. Japan, for example, matures part of its whisky in casks built from the indigenous mizunara oak tree (Quercus mongolica).

94. What Is a Barrel?

A barrel is an alcohol-storing container made of American white oak and has a maximum volume of 200 liters (53 gallons). Almost all American whiskey matures in this type of vessel. Barrels may also be used by sherry bodegas to prepare them for a second act—use in the Scottish malt whisky industry.

95. How Is a Barrel Made?

“Raising a barrel” at the Bluegrass Cooperage, Louisville, Kentucky.

An oak has to grow between eighty and ninety years before it is suitable to be used as material for barrels. The trees are specially selected and felled. After having lain in the open air for six months, they are put in a drying oven until the humidity in the wood is reduced to 12 percent. The tree is then split in two, and each part is sawed in half again to get four pieces. From each piece, four staves are sawed in such a way that the orientation of the growth rings reduces the risk of a leaky barrel. The planks, approximately thirty-eight inches long, are delivered to a cooperage and cut into staves of the desired length, as well as heads and ends. Both barrel ends are toasted lightly in a special oven. A new barrel is made (“raised”) using twenty-nine to thirty-one staves, held together by a temporary ring. It will then be steam heated to make the wood more pliable. The barrel is tightened with a winch and fitted with temporary hoops that come from a large roll of flexible iron bands. Then it’s ready to be toasted and charred from the inside. When charring is done, the barrel is lightly scraped and the head and end are fitted, after which the barrel has to cool off. The temporary hoops are removed, and when the barrel is cooled enough, the permanent hoops—usually six in total—are placed on it. The cooper bores the bunghole in the widest stave. A gallon of water is poured into the barrel, after which it is sealed with a rubber stop and pressurized to check for leakages. At the end of the production line, each barrel is inspected for quality and any existing leaks are repaired.

There are three large cooperages in the United States and two in Scotland. Some distilleries, mainly in Scotland and Ireland, have on-site cooperages.

96. Why Are New Barrels Charred or Toasted?

Toasting or charring a barrel “opens” the wood up so that the whisky stored inside can physically and chemically interact with it. Experts estimate that at least 60 percent of the aroma and taste of a whisky comes from the wood’s influence.

97. What Are the Main Characteristics of American Oak?

American oak carries sweeter notes, such as vanilla, citrus, and coconut, but also spicier ones such as nutmeg and cloves. It may also give off less color, especially when used a second or third time, but this isn’t always the case.

98. What Are the Main Characteristics of European Oak?

European oak usually carries darker notes, such as dried fruit and toffee. It may give the whisky a more intense color.

99. What Types of Barrels Are Used?

The whisky world has never been too picky regarding the type of barrel. The Scots have a preference for barrels (or casks, as they call them) that previously contained bourbon, sherry, port, rum, or wine. Each of these types of cask has a different name, as described in the following entries.

100. What Is a Butt?

A butt is a cask that holds between 500 and 600 liters; it is usually used for maturing sherry.

101. What Is a Puncheon?

A puncheon has the same volume as a butt, but it has a somewhat shorter and thicker shape. Puncheons are usually used for maturing sherry before being used to mature whisky.

102. What Is a Hogshead?

A hogshead is a vessel slightly larger than a barrel; it can hold up to 250 liters of liquid. Hogsheads are delivered ready-made from a cooperage but can also be made from a barrel by extending it with a few extra staves and replacing the head and the end. They can be used for maturing sherry prior to maturing whisky.

103. What Is a Port Pipe?

A port pipe is a type of cask used to mature port. Some malt distillers love to treat their whisky with an extra maturation in a port pipe after it has spent years in a former bourbon barrel. Finishing whisky in a separate barrel (see entry 115) adds extra nuances in flavor and aroma. Balvenie Portwood and Glenmorangie Quinta Ruban are fine examples of portwood finished single malts.

104. What Is a Quarter Cask?

A quarter cask is no longer considered a standard size. Originally, a quarter cask was a quarter of a sherry butt, holding 150 liters; however, quarter casks of 180 liters are no exception today. Quarter casks are used to speed up maturation, having a greater surface-to-volume ratio than larger cask types. The smaller the cask, the greater the wood influence on the spirit. Laphroaig has named one of its expressions Quarter Cask—a single malt that spent some time maturing in 125-liter casks. Quarter casks are the same height as bourbon barrels but more slender.

105. What Is Virgin Oak?

Virgin oak is a brand-new oak cask that hasn’t previously held any liquid. Various single malts are currently being matured in such casks, prime examples being Deanston Virgin Oak and Glen Garioch Virgin Oak. This type of single malt is slowly gaining popularity. Distillers who traditionally reuse casks can experiment with this type of cask to see what it does to their spirit. Using a new cask results in more color and flavor being released rapidly, possibly changing the traditional flavor profile of an established whisky.

106. What Is the Angels’ Share?

Oak casks and barrels breathe, which is why some of their content evaporates during maturation. The percentage of liquid that evaporates annually from a cask is called the angels’ share. This number may vary depending on the location of the warehouse, so in Scotland, for example, one might see an evaporation percentage between 1.5 percent and 2.5 percent per year, while in hotter climates, like India, it may be as high as 12 percent.

During maturation in Scotland, the percentage of alcohol slowly decreases because more alcohol than water evaporates with the angels’ share due to the relatively mild climate, the humidity level, and the relatively small changes in temperature between summer and winter.

107. What Is the Difference Between First Fill and Refill Casks?

First fill casks are those filled with spirit for the first time, after being used to store a different alcoholic liquid (like sherry or bourbon). When they’ve been used for spirit more than once, they become refill casks.

108. How Many Times Can a Barrel Be Used?

An oak needs to grow at least eighty years before it can efficiently be turned into planks of the desired thickness, porosity, and pliability for making a whisky barrel or cask.

Each cask will be used two or three times in its life, depending on how long each maturation cycle takes and where it’s stored. A barrel for maturing straight bourbon can be used only one time for that purpose. Once in its lifetime, a cask can be rejuvenated by scraping the inside and recharring. The head and end are replaced as well. The Speyside Cooperage, one of Scotland’s largest cooperages, uses this technique on many of their casks each year.

Reassembling a cask in the Speyside Cooperage, Scotland.

109. What Happens During Maturation?

During maturation, the liquid inside the cask expands when the temperature rises and contracts when it gets lower. This slow pulsating motion causes the liquid to take on the color, aroma, and flavor of the wood. A new cask will transfer more of its characteristics onto the whisky than a cask that has been used before. The wood, in turn, extracts aromas and flavors from the whisky, while the charred inside of the cask acts as a filter for impurities.

110. Does the Size of the Cask Influence the Maturation Process?

Yes—the smaller the cask, the greater the influence of the wood on the whisky. This has to do with the surface-to-volume ratio. Whisky matured in a quarter cask (125 liters) may develop as much flavor in six years as ten-year-old whisky maturing in a hogshead (250 liters).

111. Does Location Influence Maturation?

Both the microclimate affecting the geographical location of the warehouse as well as the location in the warehouse itself play a role during maturation. The higher in the warehouse the cask is stored, the higher the temperature and the more intense the interaction between wood and liquid. In Scotland the temperature in a warehouse remains relatively stable throughout the year, unlike in, for example, Kentucky or India, where temperatures can vary immensely between seasons. This is why a few distilleries use climate control units where temperatures are monitored and adjusted automatically. Humidity is another huge factor to take into account. Generally speaking, the drier the climate and the larger the temperature fluctuations, the more water evaporates from the whisky, producing a spirit with a higher alcohol content.

112. At What Alcohol Percentage Is Spirit Poured into the Cask?

Most whisky in Scotland is poured into the cask at 63.5 percent ABV, although higher percentages—up to 70 percent ABV—have been observed.

113. At What Alcohol Percentage Does Whisky Come Out of the Cask?

During maturation, the cask loses about 2 percent of its contents annually. This affects the ABV differently in different climates. In Scotland, where the humidity is relatively high and the temperature consistent, more alcohol than water evaporates by volume, so the longer the whisky matures, the lower the ABV gets. It’s rare for Scotch whisky to leave the cask at the 63.5 percent ABV it entered at—58 percent ABV is more common. In Kentucky, the opposite is true: as a consequence of the lower humidity and great fluctuations in temperature throughout the year, more water than alcohol evaporates. Whiskey might leave the barrel at 67 percent ABV or more. The master blender decides when it’s time to bottle the whisky and at what strength, but in order to consider a spirit whisky, the minimum legal limit is 40 percent ABV. This regulation was introduced in Scotland and England at the turn of the nineteenth century in order to assure a standard of quality.

Casks at Bunnahabhain Distillery, bordering the Sound of Islay.

114. What Is Reracking?

The master blender monitors the spirit’s quality throughout maturation by testing samples at regular intervals. If a whisky is not maturing as expected, the whisky will be reracked—transferred to another cask mid-cycle—in the hopes of achieving a better result. If a cask is showing signs of leakage that can’t be repaired, the whisky will be reracked as well.

115. What Is Wood Finish or Extra Maturation?

When a whisky has been maturing in one type of cask for a long period of time and is then transferred into another type of cask for a short period before bottling, the procedure is called wood finish or extra maturation. This is done to add an extra layer of flavors to the whisky. Some whisky blenders use the term marrying to describe this process of adding additional flavors by way of extra maturation. Scottish Glenmorangie is a pioneer in this area (see images).

116. Does the Wood Influence the Final Flavor of Whisky?

From left: Matured in ex-bourbon casks; extra-matured in ex-sherry casks; extra-matured in ex-port casks; extra-matured in ex-sauternes casks.

About 60 percent of whisky’s taste is derived from the cask in which it matured, so, yes, the wood has a huge influence on taste. A poor-quality distillate cannot be improved in a fine cask, but a fine distillate can be ruined in a bad cask, the latter either being poorly manufactured or having off notes from previous contents that will negatively influence the taste and aroma of the eventual whisky.

117. How Many Single Malts Come from Scotland?

There are about 120 working distilleries in Scotland. However, every distillery makes various versions of their single malt and may give them different names. The Macallan, for example, produces a special series of single malts called Gold, Amber, Sienna, and Ruby. In chapter 9 you’ll find a list of Scottish malt whisky distilleries with a map of their locations (see Distilleries in Scotland).Grain Whisky

118. How Is Grain Whisky Made?

Grain whisky is made of corn or wheat. The grain of choice is first cooked in an industrial pressure cooker, which softens the starch. A small amount of malted barley, rich in enzymes, is then added to convert the starch into fermentable sugars. The fermentation of this sugar-rich liquid is similar to pot still distillation. The wash enters a column still at a low ABV and leaves it as a fluid with a high alcohol content. This column distillation is usually done in two steps, using two connected columns.

119. What Is Column Distillation?

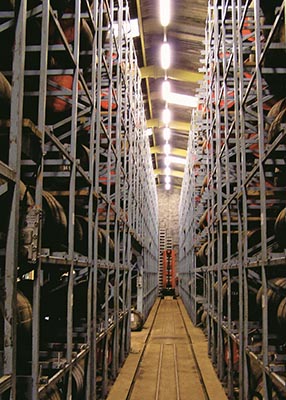

Contrary to pot still distillation, which is a batch-oriented process whereby the stills need to cool down and be cleaned after each round of distilling before being heated up again, column still distillation is a continuous process. One of the first column stills was designed by Aeneas Coffey, an Irish distiller, and patented in the first half of the nineteenth century. The structure usually consists of two interconnected columns, an analyzer and a rectifier. Both are divided into a series of compartments, separated by perforated plates.

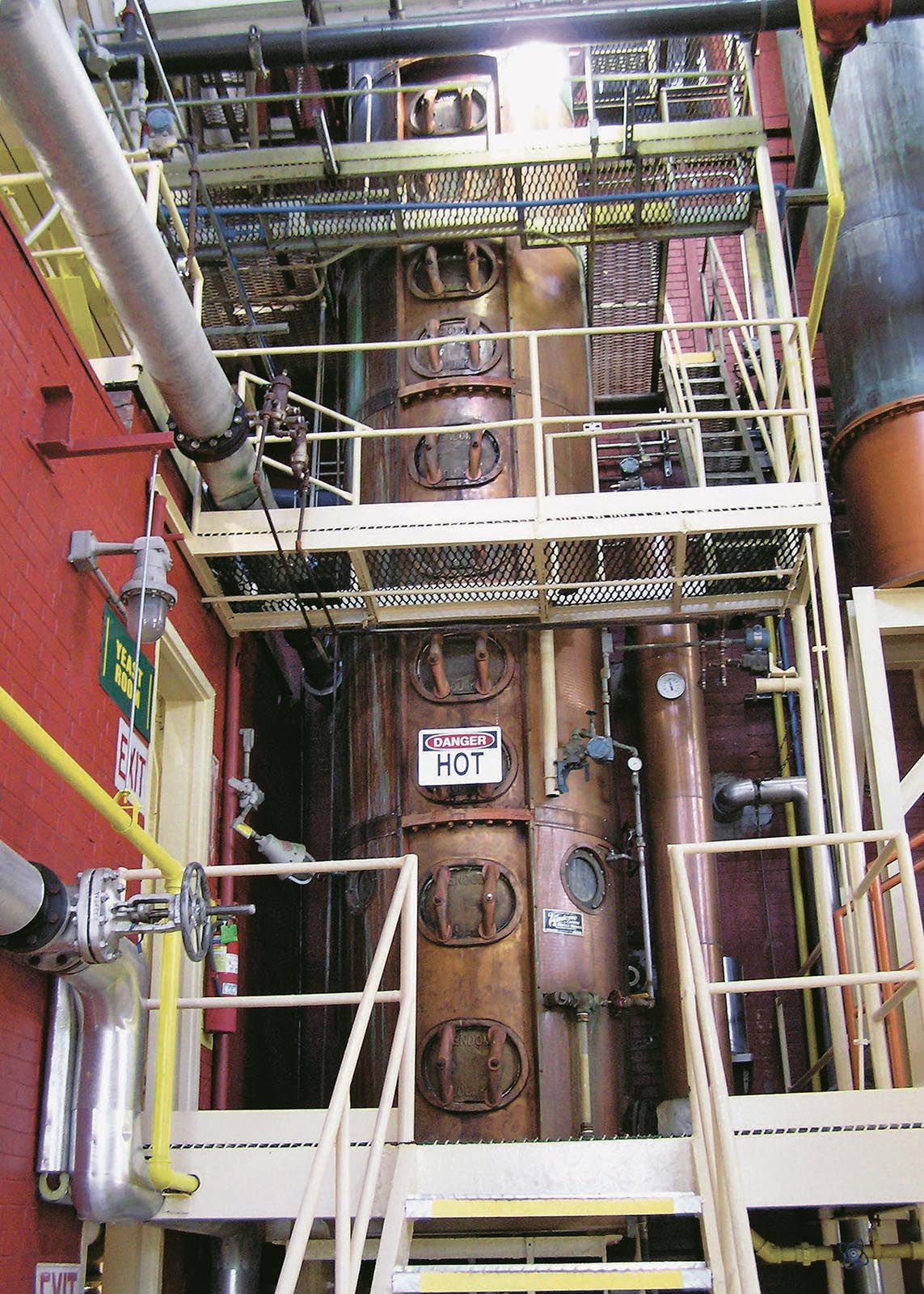

The gigantic column stills at Girvan Distillery.

120. How Does the Analyzer Work?

Wash, the low-alcohol fluid retained after fermentation, is fed into the column through a copper pipe attached to the top of the analyzer, where the wash is poured over the first perforated plate. The liquid starts to trickle through the compartments and makes its way to the bottom of the column while steam simultaneously rises from the bottom and ascends through the plates, making contact with the liquid and stripping it of alcohol.

121. How Does the Rectifier Work?

Left: Scale model of the inside of a column still. Right: Column still at Cooley, Ireland.

The alcoholic fumes travel from the analyzer through a pipe to the bottom of the rectifier and start ascending again. Since the various alcohols fractionate at different temperatures, the spirit divides into various parts. The heavier alcohols condense back into liquid form and lie on the plates. Only the lighter alcoholic vapors make it to the top of the column and are collected in a condenser. The eventual spirit contains approximately 90 to 94.8 percent ABV.

122. How Does Grain Whisky Mature?

Most grain whisky matures in casks, previously used for bourbon, made of American white oak. As with malt whisky, the spirit has to mature at least three years before it can be considered whisky. The casks are stored in racked warehouses.

123. How Many Grain Distilleries Does Scotland Have?

Grain whisky in Scotland is made in huge quantities by seven large distilleries: Cameron Bridge, Girvan, Glen Turner/Starlaw, Invergordon, Loch Lomond, North British, and Strathclyde. The number of grain whisky distilleries used to be even greater and included some famous ones that have been closed or demolished, like Cambus, Dumbarton, Garnheath, and Port Dundas. Some of their whisky can still be found on the market today.

Blended Whisky

124. How Is Blended Whisky Made?

Blended whisky is composed of various mature whiskies. The backbone of a blended Scotch whisky is always a grain whisky, made from either corn or wheat, in a column still. After maturation, a percentage of mature single malts is added to create a particular flavor profile. The flavor and composition are unique to each blend, and the recipe is a secret of the master blender. Blending is sometimes compared to composing a symphony—each whisky plays its part and contributes its own note to the end product, making the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

125. How Do You Make a Good Blend?

To create a good blend, the master blender regularly tests samples from various casks of single malt whiskies to analyze how they develop over time. For this, he predominantly uses his sense of smell. A liquid library of samples is created to ensure that different components of the flavor remain easily identifiable.

The blender is extremely knowledgeable about the difference in taste of each malt whisky and can effortlessly find an adequate replacement should a certain brand temporarily run out of stock. A handy tool of the trade is a malt classification system widely embraced by the industry. It can be found in Richard Paterson’s excellent book Goodness Nose. Finally, choosing the right casks is key to a successful blend. Distilling whisky is a craft; blending whisky is an art.

Rachel Barrie in her blending lab.

126. How Many Blends Are There?

Some of the well-known brands of blended whisky are Johnnie Walker, Ballantine’s, The Famous Grouse, Chivas, Dewar’s, White Horse, Black & White, and Cutty Sark, but countless others have been developed over the past 150 years. Most of the blends got their names from small family enterprises founded in the second part of the nineteenth century, when blending became legal. Apart from these household names, many cleverly named blends appear on store shelves. They are made to order, tailored to the customer’s specifications, all following a different recipe. In countries that allow liquor to be sold in supermarkets, it is not unusual to see a house blend specially developed for certain chains of stores.

127. Who Was Andrew Usher?

This Scottish wine and liquor merchant is considered the father of blended whisky. He was one of the first whisky producers who took advantage of a change in British law around 1860 that allowed blending distillates made from different grains. According to legend, Usher’s mother taught him how to create whisky blends at her kitchen table.

128. Who Was Johnnie Walker?

John Walker owned a grocery shop in Kilmarnock, Scotland, in the 1820s. When the shop was severely damaged by a flood, John’s son Alexander turned a disaster into a fortune by turning the company into a whisky wholesale business. To create a name for the brand in other parts of the world, Alexander Walker made deals with ship captains in Glasgow Harbour. They would transport his whisky to the far corners of the world and receive part of the profit in exchange. One century later, Johnnie Walker Red Label had become one of the best-known blended whiskies in the world. Peter Brown designed the famous logo of the striding man in 1908. Sometimes he marches from left to right, other times from right to left.

129. Who Was George Ballantine?

Archibald Ballantine was a farmer from Peebles in the Scottish Borders region. When his son George turned thirteen, he brought him to Edinburgh, where the boy was to apprentice with grocery and wine merchant Andrew Hunter. Six years later, in 1887, George opened his own grocery store in Cowgate, near Edinburgh Castle. From there he built an empire that was eventually acquired by Pernod Ricard, a French beverage company.

George was good friends with whisky distiller Andrew Usher and learned a lot about blending whisky from him. George put Ballantine’s on the Scottish market, while his sons Archibald and George Junior developed the brand further in Edinburgh and Glasgow, respectively. When Queen Victoria honored the company with a Royal Warrant at the turn of the nineteenth century, the brand was propelled to international fame.

130. Where Does the Name Famous Grouse Originate?

In 1869, Matthew Gloag & Son, founded in 1800, launched a blended Scotch named The Grouse. Soon it was so successful that people started referring to it as the famous Grouse. Gloag appropriately registered this trade name on August 12, 1905, or “the Glorious Twelfth,” which refers to the start of grouse season in Great Britain. The brand is steeped in tradition, and the descendants of the founding family are still involved with the business. The logo is derived from an original drawing, supposedly done by the founder’s aunt. The bird was stylized regularly over time.

131. Who Were the Chivas Brothers?

Brothers John and James Chivas left their parents’ farm in 1836 to try their luck near Aberdeen, Scotland. It took two years before James was hired as an assistant in Edward’s Grocery Store on King Street. The shop was popular among the town’s elite because of its wide range of products. After James became a partner in the company, he hired his brother and they became passionate about providing the highest-quality products. The brothers expanded the business with catering facilities, and soon they were purchasing whisky by the cask. Both brothers had excellent noses, and their premium blend Chivas Regal took off worldwide. They were bought out by Canadian company Seagram around 1950, which brought Chivas Regal to an even larger stage. The shop in Aberdeen doesn’t exist anymore, but the name lives on, as a whisky and as a company, since current owner Pernod Ricard consolidated all its whisky distilleries, including the beautiful old Strathisla in Keith, under the name Chivas Brothers Ltd.

132. Who Was Tommy Dewar?

The Dewar’s brand was built by John Alexander and Tommy, sons of founder John Dewar. While John held down the fort in Scotland, younger brother Tommy embarked on a world tour. With his flamboyant appearance, Tommy managed to make Dewar’s known worldwide within twenty years. During his travels, he wrote a book called A Ramble Round the Globe. He also dabbled in politics and was appointed sheriff of London more than once. The term Dewarism was coined in honor of his witty one-liners.

133. What Do the Initials in J&B Represent?

The story of this brand hides a great romance at its origins. Giacomo Justerini, son of an Italian distiller, was absolutely mesmerized by Italian soprano Margherita Bellino’s performance and fell in love with her. In 1749 he followed her to England, and although their love didn’t last, his knack for business did. He became a successful wine and spirit merchant in London, selling the business to his partner after eleven years and returning to Italy. In 1831 the well-established company was sold to Alfred Brooks, who renamed it Justerini & Brooks. Around 1884 the company started to lay down stocks of whisky and had a blend created: J&B Club, the forerunner of J&B Rare blended Scotch whisky. This light and smooth blend is excellent in a cocktail.

134. Where Does the Name Black & White Originate?

James Buchanan was Tommy Dewar’s biggest rival—not only as a whisky maker but also as a fan of horse racing. Both men owned a considerable stable of thoroughbreds. When Buchanan introduced a new blend featuring a white label with his name printed in black letters, it did not take long for customers to ask for the “Black and White.” A Scottie and a Westie, the canine mascots of the brand, were added to the label many years later. Buchanan was one of the first whisky barons to deliver whisky exclusively to the House of Lords, the upper house of British Parliament.

James Buchanan

135. Who Is Behind the White Horse Label?

White Horse is a legendary Scottish blend named after a famous pub in Edinburgh, the White Horse Cellar Inn. There is more than a drop of Lagavulin single malt in the White Horse. Not surprisingly so, since both brands and distilleries were once owned by the same man, Peter Mackie. Restless Peter, as he was nicknamed, was energetic and highly competitive and came with a short fuse. For a long time, he quarreled with his neighbor Laphroaig, whose single malt had been represented by the Mackie family for many years. When Laphroaig one-sidedly ended the agreement, Mackie went through the roof and tried to make life as difficult as possible for the man he used to do business with. He even tried to copy Laphroaig’s whisky by building a second, smaller distillery called Malt Mill within his main distillery, Lagavulin. He did not succeed, but his blend White Horse is still in existence and is currently owned by Diageo.

136. What Is the Story Behind Cutty Sark?

“Tam o’ Shanter” is one of Robert Burns’s most famous poems. It served as the inspiration for a whisky brand created and launched in 1923. The poem, written in 1790, includes a paragraph describing poor Tam being pursued by a fast-running wild witch wearing a short nightgown known as a cutty sark. Almost eighty years later, in 1870, Captain Jock Willis used the name for his new tea clipper, designed to sail unusually fast for its time. Its maiden trip brought the Cutty Sark from London to Shanghai, and the ship would complete eight such expeditions, becoming famous in its own right.

In 1923, London-based wine and whisky merchant Berry Brothers & Rudd wanted to launch a new blended, easy-drinking whisky in the United States (mind you, this was during Prohibition!) and hired a Scottish artist, James McBey, to come up with a catchy name. Since the ship had been in the news constantly, Cutty Sark was an obvious choice. From then on it was smooth sailing for the blend.

137. What Other Scottish Blends Are Available?

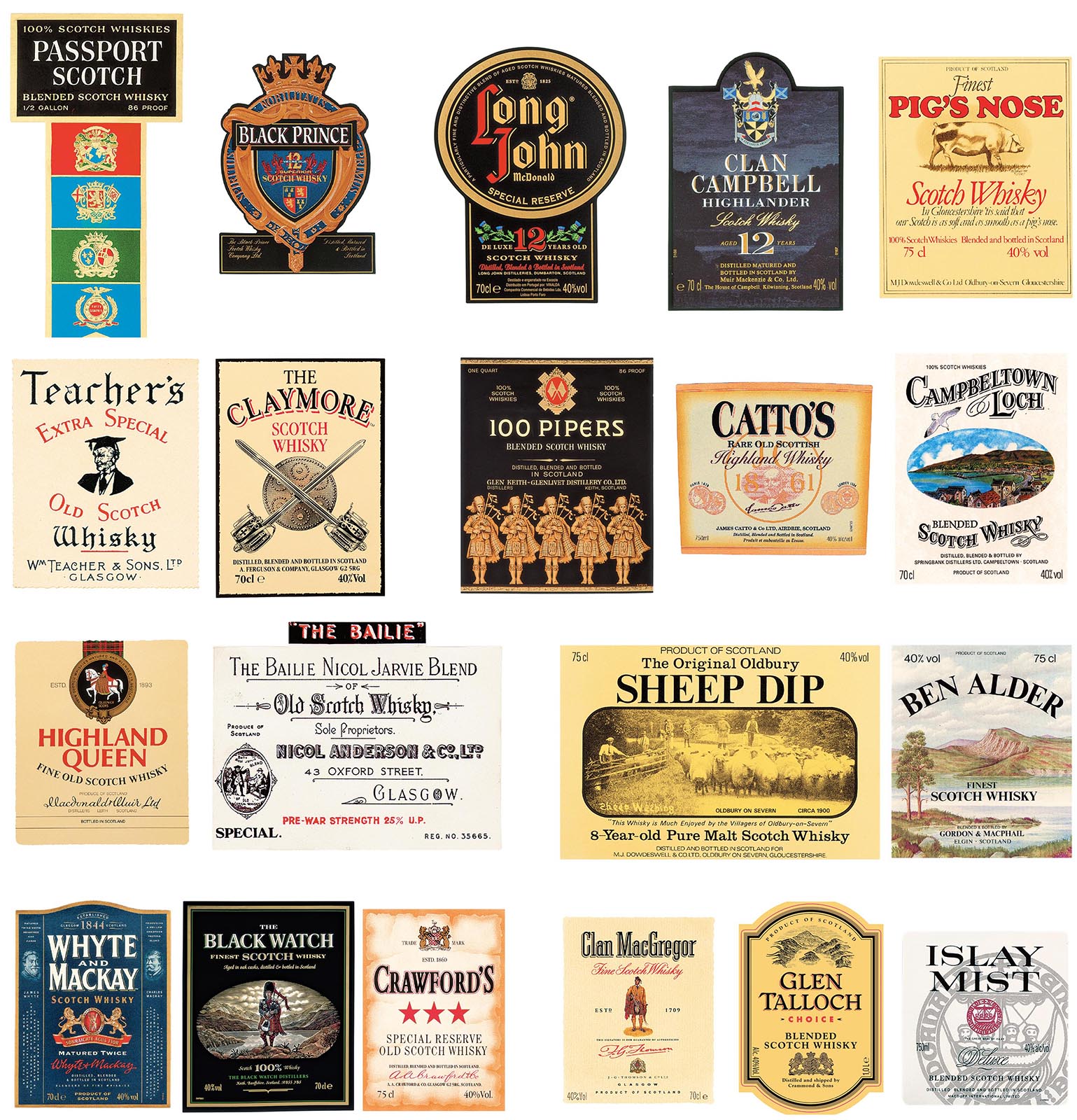

There are countless Scottish blends, but the following is a non-exhaustive list—in alphabetical order—of blends that are available worldwide: the Antiquary, Bell’s, Ben Alder, Black Bottle, Black Cock, Black Prince, Black Watch, Blue Hanger, BNJ, Buchanan’s, Campbeltown Loch, Catto’s, Clan Campbell, Clan MacGregor, Claymore, Crawford’s, Dimple, Grant’s Family Reserve, Haig, Hanky Bannister, High Commissioner, Highland Queen, Islay Mist, Lang’s, Long John, Mackinlay, Old Parr, 100 Pipers, Passport, Pig’s Nose, Sheep Dip, Six Isles, Stewart’s Cream of the Barley, Teacher’s, Té Bheag, the Talisman, Vat 69, Whyte and Mackay, William Lawson’s, and Ye Monks.

138. Why Are There So Many Blended Whiskies?

Between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, a true cottage industry developed in the Scottish Highlands. Hundreds of farmersturned-distillers made their own expressions of single malt whisky. Export to the Lowlands or England was virtually nonexistent, since the population of the southern part of Great Britain preferred brandy (cognac) or gin. During the nineteenth century, five important events reshaped the Scottish whisky landscape and in its wake the consumption pattern among the English.

1. The Invention of the Column Still

In 1827, Irish distiller Robert Stein patented a still that made continuous distillation possible. It wasn’t a pot still such as the Highlanders in Scotland used, but a several-foot-high column. Another Irishman, named Aeneas Coffey, improved the column and registered a patent for his idea in 1830. The column still, sometimes referred to as a Coffey still, was born. From that moment on, it was possible to distill alcohol from various types of grains on a large industrial scale. The Irish distillers didn’t like the invention and ignored it, whereas the Scottish Lowlanders embraced the new distilling device. They used it to make huge amounts of cheap grain whisky, less outspoken in flavor than the distinctive and more expensive malt whiskies from the Highlands, which at the time often had smoky or medicinal notes.

2. Law Changes

The second event was the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws. Up to that point, distillers were allowed to use only barley for making whisky, but the new law allowed for cheaper grains, like corn and wheat, to be used for distilling alcohol. In 1860, another breakthrough came in the form of a law change in Scotland that allowed the blending of different distillates made from different base materials. Andrew Usher was among the first to see an excellent opportunity for increasing his market share and became the de facto “father of blending.” Usher purchased casks of single malts from individual Highlands distillers and blended their product with cheap grain alcohol. He also blended malt whiskies with one another, calling the end product Usher’s Old Vatted Glenlivet (sometimes spelled Glenlivat). It did not take long before other wine and liquor merchants followed his example. The Chivas Brothers started their blending business in Aberdeen, and John Dewar and Alexander Bell followed suit in Perth. William Teacher was running his blending business in Glasgow, and elsewhere John Walker, George Ballantine, Robert Haig, Matthew Gloag, and James Buchanan practiced the art of blending whisky. Most of these family names live on as famous whisky brands today.

“Whisky is liquid sunshine.”

George Bernard Shaw

3. A Disaster in France

The third event took place in France. In 1863 a blight plagued the French vineyards and decimated nearly half of them within two decades. The disease was caused by a nasty bug accidentally imported from America, the Phylloxera vastratix. Cognac became scarce and expensive, and the English had to look elsewhere for their tipple of choice. They found an alternative in the new drink being produced at home—blended whisky. The drink became an instant success, envied by the Highlanders, with their distinctive single malts.

4. Compromised Quality

The fourth event was a crime. At the turn of the nineteenth century, whisky consumption was booming and some blenders cut corners in an attempt to optimize their profits, which inevitably compromised the quality of the product. The Pattison brothers caused a huge stir in the Scottish whisky industry when it was discovered that they had doctored their drink by mixing immature grain whisky with fine single malts and promoted it as a premium whisky and largely inflated their profits. The Pattisons were found guilty of fraud and sent to prison. Around 1917, their wrongdoings led to a law in which Scotch whisky was defined in new, stricter terms—it had to mature for at least three years in oak casks and had to be bottled at a minimum of 40 percent ABV. This quality control facilitated acceptance and appreciation of blended Scotch whisky among consumers.

Pattisons’ ad.

5. International Conquest

Blended whisky performed well outside of Scotland and England as a replacement for cognac. When famous jazz musicians and Hollywood movie stars openly pledged their allegiance to Scotch, its export grew in an unprecedented way. Various blends became “rock stars” in their own right. Dewar’s still is one of the bestselling blends in the United States, and Johnnie Walker is the number one bestseller worldwide in the blended whisky category. Sometimes it seems that single malt whisky plays the main role in the whisky world, but numbers and figures show a different story. More than 85 percent of all Scotch whisky sold around the planet is of the blended variety. Today the famous brands are no longer owned by the founding families. Save one or two, they have all been bought by the larger companies like Bacardi (Dewar’s), Diageo (Bell’s and Johnnie Walker), Beam Suntory (Teacher’s), and Pernod Ricard (Chivas and Ballantine’s). Many of these big conglomerates own grain distilleries as well as great numbers of single malt distilleries. That is a strategic choice, because those who want to create a beautiful blended whisky need access to a regular, reliable supply of single malts. Therefore, these multinational companies regularly swap casks with one another without compensation, to offer their own master blenders a greater palate of choices. This is where single malt and grain whisky meet.

A bottle of Haig blended scotch in the dressing room of jazz pianist Fats Waller (1904–43).

Irish Whiskey

139. How Is Irish Whiskey Made?

The former Jameson Distillery in Dublin now houses a beautiful whiskey museum.

The Irish, credited by many as the inventors of whiskey, produce single malts as well as single grains and blends. Their mode d’emploi is similar to that of their Scottish neighbors, although they rarely use peat smoke for drying the malt. An exception to that rule is the smoky Connemara, produced at Cooley Distillery. But there is one specific category exclusively made in Ireland—single pot still whiskey.

140. What Is Single Pot Still Whiskey?

Cooley’s pot stills.

The Irish saw an increase in taxes on malted barley in the nineteenth century. To cut costs, the large Irish distillers decided to use a greater percentage of unmalted barley, mixing it with the malted variety. Currently, the usual ratio is 60:40 in favor of unmalted barley, but the percentages can vary per brand. This particular balance gives traditional Irish single pot still whiskey its distinctive spicy-apple-linseed character and its smooth, oily body.

141. How Is Single Pot Still Whiskey Made?

Traditional Irish single pot still whiskey is triple distilled in pot stills. The first round takes place in the wash still, usually aided by a column to promote reflux. The spirit is rid of its heavier elements and collected at 25 percent ABV for the heavier expressions, and at 38 percent ABV for the lighter ones, depending on what style of whiskey the distiller is going for. In the second, intermediate (or feints) still, the stream of alcohol is separated. The weaker feints (between 45 and 47 percent ABV) are caught and redistilled into heavy spirit. The stronger feints (between 75 and 85 percent) produce a lighter spirit. The spirit still works as a regular still in which only the heart of the run is used for making the eventual whiskey. Since Irish distillers produce a large variety of spirits, the distilling regimen varies accordingly—with different filling levels and cut points in the intermediate and spirit stills.

142. What Is Potcheen?

“Illegally” produced whiskey—without a legally acquired license and its associated regulations—is called “potcheen,” whereas the legal product is sometimes referred to by the tongue-in-cheek term parliament whiskey. Potcheen (also spelled as “poitín”) is colorless and not matured. It is often consumed in secret, but you can also find it bottled on the shelf in a liquor store. This is, in fact, the legally produced spirit from a legal distillery, but it cannot be called whiskey due to its lack of cask maturation.

143. How Does Irish Whiskey Mature?

The Irish distillers rarely use dunnage warehouses. Most Irish whiskey matures in racked warehouses where the casks are palletized in an upright position. A variety of casks are used, some of which may have previously held other liquids, such as sherry, port, bourbon, and Madeira, but the majority of the spirit is poured into first fill casks.

144. How Many Irish Distilleries Are There?

The Irish economy had to overcome many adversities in the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth: the Great Potato Famine, Prohibition in the United States, the 1929 Wall Street Crash and its worldwide rippling effects, and economic wars with England. As a result, the Irish whiskey industry was reduced from a major force into a marginal player on the world market. Closures and mergers ensued, resulting in only two companies left standing: Irish Distillers in the Irish Republic and Bushmills in Northern Ireland.

Cooley joined the ranks in 1989, becoming a forerunner of the industry upsurge in the decades that followed. As of today, more than twelve distilleries throughout both countries have caused the phoenix that is Irish whiskey to rise from the ashes with a new lease on life (see a map of all their locations). Irish Distillers (owned by Pernod Ricard) and Cooley/Kilbeggan (owned by Beam Suntory) are still the major players in the Republic, as is Bushmills (owned by Jose Cuervo) in Northern Ireland.

The decommissioned pot stills of Powers: an industrial monument gracing the courtyard of this former distillery in Dublin. The buildings now house the National College of Art and Design.

In the village of Kilbeggan stands the oldest working distillery in Ireland. Founded as Brusna and later known as Locke’s, currently the distillery carries the same name as the village.

145. What Are the Well-Known Irish Whiskey Brands?

Jameson has been the market leader among Irish blended whiskey for a long time. Tullamore Dew, the original ingredient in Irish coffee, takes second place. Other far-reaching brands are Bushmills/Black Bush (malt whiskey and blended whiskey), Powers (blend and single pot still), Paddy (blend), Redbreast and Green Spot (single pot still), Kilbeggan (blended and grain), and Connemara and Tyrconnell (single malts). One of my personal favorites is Writers Tears, a pot still blend.

Bourbon

146. How Is Bourbon Made?

Bourbon is made from a mixture of grains consisting of at least 51 percent corn, with the addition of rye and/or wheat and malted barley. The corn adds a fatty sweetness to the distillate and provides the “backbone” of the drink. A small portion of malted barley promotes the formation of enzymes needed to convert the starch into sugars: the wheat will make the bourbon softer and smoother, whereas rye will give the drink a spicier character. Wheat and rye are called “flavor grains,” and the corn-to-flavor-grains ratio has a huge impact on the aroma and taste of the end product.

Clockwise from top left: corn; rye; barley; wheat.

147. What Is a Mash Bill?

The mash bill is a recipe showing the percentage of grains used for a specific bourbon. Distilleries often use more than one mash bill and in doing so can create a huge variety of bourbons. Most distillers carefully keep their mash bills a secret. Not the case with Four Roses, a company that uses two different recipes: “OB,” containing 60 percent corn, 35 percent rye, and 5 percent malted barley; and “OE,” with the ratio of the same ingredients at 75 percent, 20 percent, and 5 percent. Maker’s Mark is known for using wheat instead of rye as its flavor grain. Its mash bill is 70 percent corn, 16 percent red winter wheat, and 14 percent malted barley.

148. What Is a Mash Cooker?

The mash cooker at Buffalo Trace in Frankfort, Kentucky.

A mash cooker is a kind of a pressure cooker. After the corn has been milled and mixed with water, it goes into the mash cooker. When it’s done cooking, it’s cooled and rye and/or wheat are added to it. This mixture is cooked at a lower temperature and cooled down a second time. Only then is the small percentage of malted barley added.

“Tell me what brand of whiskey General Grant drinks. I would like to send a barrel of it to my other generals.”

Abraham Lincoln

At Woodford Reserve in Versailles, Kentucky, the mash cooker and the fermentation vessels are in the same room.

Most bourbons are made with sour mash. This is the by-product of a distillation round in the form of an acidic liquid that is added to the next batch during fermentation. Sour mash keeps the pH value at the desired level and keeps bacteria at bay. The amount of added sour mash influences the percentage of sugars in the mash—when trying to achieve a fresh and light bourbon, less sour mash is added.

150. What Are Fermenters?

The fermenters in the large bourbon distilleries are gigantic vessels, like this one at Buffalo Trace in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Fermenters are yeast vessels (they’re called washbacks in Scotland). They are made from wood, as well as stainless steel. Most distillers in the United States use a proprietary yeast strain that is kept alive at the distillery. One strain is common, but some distillers use two, three, or more. For example, Four Roses is famous for using five different yeast strains. Fermentation takes up to three days, resulting in a “beer” containing 5 to 6 percent ABV.

The beer still at Four Roses, Lawrenceburg, Kentucky.

151. What Happens in the Beer Still?

The “beer” from the fermenter is distilled in a single column still. It is poured in from the top; steam enters the column at the bottom. The beer trickles through perforated plates on its way down and meets the ascending steam that strips it of alcohol. These alcoholic fumes then condense into a liquid containing 55 to 60 percent alcohol. A second distilling round may take place in a piece of equipment called a thumper or a doubler, depending on the type.

152. What Is a Thumper?

A thumper is a huge copper kettle containing water. The alcohol fumes pass through it. Heavier elements are withdrawn and the liquid is purified, while concentrating the alcohol even further. The equipment takes its name from the thumping sound the kettle makes when it’s working.

153. What Is a Doubler?

Instead of a thumper, a doubler might be used for the second round of distillation. It somewhat resembles a pot still and works similarly (see entry 64).

154. What Are Heads and Tails?

Heads and tails are the equivalents of foreshots and feints in single malt whisky production (see entries 78 and 80).

155. What Is the Tail Box?

The tail box is the equivalent of the spirit safe in a single malt whisky distillery (see entry 77).

White dog is the colorless liquid that comes from the still before it is poured into a barrel. By law, white dog cannot be more than 80 percent ABV, and most distillers stay far under that percentage. The less alcohol, the oilier the white dog.

157. How Long Does Bourbon Mature?

There is no legal minimum number of years for bourbon to mature. The distillate may be called bourbon one day after it has left the still. Straight bourbon, which is more regulated, needs to mature at least two years (see entry 166).

158. What Kind of Barrel Is Used for Bourbon Maturation?

In the United States, a distillate can be called bourbon only when it has matured in brand-new charred barrels made of American white oak.

Clockwise from top left: This thumper belongs to Wild Turkey Distillery in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky; the doubler at Four Roses used for the second distillation; in front of Four Roses’ tail box stands a glass of white dog.

159. What Types of Warehouses Are Used for Maturing Bourbon?

The characteristic red shutters on the black warehouses at Maker’s Mark, Loretto, Kentucky.

Most warehouses in the United States are many stories high and equipped with wooden or steel racks. The exterior is often clad in corrugated iron, but some are brick buildings, such as the warehouse at Buffalo Trace, in Frankfort, Kentucky, where the famous single barrel bourbon Blanton’s matures. Four Roses uses very low-rise buildings— barrels can be stacked only six high.

160. Does Bourbon Have an Angels’ Share?

A warehouse owned by Heaven Hill faces the entrance of the Bourbon Heritage Center in Bardstown, Kentucky.

In the warehouses, especially in Kentucky, temperatures are very high in the summer and low in the winter, whereas the humidity is relatively low. Because of these climate conditions, more water evaporates than alcohol. It is remarkable, but after maturation, the ABV of the bourbon that comes out of the barrel may be higher than that of the white dog that entered it years earlier. So bourbon does have its angels’ share (see entry 106), but it contains less alcohol than it would in Scotland. Guess which country the angels favor!

161. What Is Barrel Dumping?

While dumping a barrel of Woodford Reserve, the distillery manager takes a sample to check the quality of the bourbon.

As soon as the master distiller has decided which barrels are ready for bottling, they are emptied into a large stainless steel gutter. This is called barrel dumping. The contents are filtered and diluted until the desired ABV percentage is reached. The contents need to be filtered because each barrel releases a small amount of charcoal along with the mature bourbon (a result of the barrel charring that was done before it was used).

162. What Is the Devil’s Cut?

When the barrel is dumped, a small amount of whiskey will stay behind in the wood. This is called the devil’s cut (the antithesis to the angels’ share—see entry 106). Jim Beam has developed a method by which the residue can be rinsed out of the barrel. They use the rinsing water to dilute one of its bourbons, called Devil’s Cut.

163. Who Was the First Whiskey Distiller in the United States?

The answer to who really was the first distiller remains a matter of debate to this day. George Thorpe is believed to have made a distillate from corn near Jamestown in 1619. Evan Williams in 1783 is a possible candidate too. Elijah Craig (who supposedly started to distill whiskey in 1789) is often dubbed the father of bourbon, but without a shred of evidence. Both Williams and Craig have a bourbon named after them.

164. Is All American Whiskey Bourbon?

Not all American whiskey is bourbon, but all bourbon is American. Originally, American whiskey was made mainly of rye. It wasn’t until later that the colonists began to distill domestic corn. American settlers claimed that the corn was given to them by Native Americans. Native Americans tell a different story: that the Pilgrim Fathers stole their hidden stock.

165. Does Bourbon Always Have to Come from Kentucky?

Bourbon can be made anywhere in the United States. The state of Kentucky has been the hub of bourbon production for decades.

166. What Is Straight Bourbon?

Production of straight bourbon has a far stricter rulebook than regular bourbon. These rules are described in the Federal Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits (27.C.F.R.5). In short:

◆ The product has to be manufactured in the United States of America.

◆ The product has to be made of a mixture of grains, containing at least 51 percent corn.

◆ The product has to be matured in new oak barrels, charred from the inside.

◆ The distillate running from the still can be no more than 160 proof (80 percent ABV).

◆ When pumped into a barrel, the distillate can be no more than 125 proof (62.5 percent ABV).

◆ The bottled product should be at least 80 proof (40 percent ABV).

◆ Maturation time has to be at least two years.

◆ Adding of coloring agents, artificial flavor compounds, or other distillates is not allowed.

◆ When maturation has taken less than four years, the age has to be mentioned on the label.

◆ When an age is mentioned on the label, it should always be the youngest whiskey in the bottle.

167. What Is Kentucky Straight Bourbon?

When “Kentucky Straight Bourbon” is on the label, the whiskey in the bottle has to be made and matured in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Maturation cannot be less than two years and one day.

168. Where Does the Name Bourbon Originate?

After the Revolutionary War, America baptized many counties and cities with French names, as a token of gratitude for the help received from France against the English. Kentucky’s Bourbon County was named after the French royal family at the time. The whiskey distilled in that county was transported to Louisiana by boat. The product was very much welcomed down South, and customers started asking for “that whiskey from Bourbon County,” which was eventually abbreviated to Bourbon.

On May 4, 1964, the U.S. Congress recognized bourbon as “a distinctive product of the United States.” Since that date, bourbon could be made anywhere in the United States.

169. Does Bourbon Always Come from the United States?

Jim Beam’s small batch bourbon series (also see entry 213).

Bourbon is officially an American product. However, this does not mean that bourbon cannot be made outside the United States. It just can’t legally be called bourbon; “bourbon-style whisk(e)y” is used instead.

170. Why Is Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey Not Called Bourbon?

Left: This wooden vessel is filled to the brim with charcoal. Jack’s white dog trickles through this layer for days before maturing in oak barrels. Right: A display dedicated to Jack Daniel, founder and namesake to one of the world’s most famous distilleries and brands, located at the visitor center in Lynchburg, Tennessee.

Although the method of production is very similar to that of bourbon, Jack Daniel’s styles itself as “Tennessee Whiskey.” Unlike with bourbon, Jack Daniel’s white dog is filtered through a thick layer of sugar maple charcoal before it is poured into a barrel.

171. What Is the Lincoln County Process?

This is a technique used in the production of Tennessee whiskey—the white dog is filtered through ten feet of sugar maple charcoal right before the liquid goes into the barrel for maturation. Charcoal filtering is an old technique used in ancient Russia for making vodka. The process in the United States gets its name from Lincoln County, which is where the Jack Daniel’s Distillery was located when it was built. The county borders were later changed, and the distillery now resides in Moore County. Remarkably, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) has not yet made a rule that whiskey made in this fashion cannot be called bourbon. George Dickel makes Tennessee whiskey too.

The distillery of George Dickel is located in Tullahoma, Tennessee, a half-hour drive from the Jack Daniel’s Distillery.

172. How Is Rye Whiskey Made?

Rye whiskey is made the same way as bourbon, except that the mash bill has at least 51 percent rye in the recipe.

173. How Long Does Rye Whiskey Mature?

There are no legal requirements regarding maturation time for rye whiskey.

174. How Is Wheat Whiskey Made?

Wheat whiskey is made the same way as bourbon, except that the mash bill has at least 51 percent wheat in the recipe.

175. How Long Must Wheat Whiskey Mature?

There are no legal requirements regarding maturation time for wheat whiskey.

176. Can Single Malt Whisk(e)y Be Made in the United States?

Single malt whisk(e)y can be made anywhere in the world. Various brands are produced in the United States, including McCarthy’s Single Malt Whiskey. It is manufactured at Clear Creek Distillery in Portland, Oregon, and spelled with an “e.”

177. What Are the Famous Bourbon Brands?

The stopper of Blanton’s Single Barrel is a racehorse figurine—a symbol of the Kentucky Derby, a race held annually in Louisville, Kentucky, on the first Saturday in May. The horse figurine comes in eight different poses. When combined, they show a racehorse in full stride. The hind leg of the horse is always engraved with one of the letters spelling “Blanton’s”: it’s a real collectors’ item.

Prohibition in the United States, from 1920 to 1933, nearly killed the entire American whiskey industry. After its repeal, a small group, located mainly in Kentucky, started to rebuild the industry. Five among them currently produce the lion’s share of Kentucky bourbon. Some famous brands are Blanton’s, Buffalo Trace, Elijah Craig, Four Roses, Heaven Hill, Jim Beam, Maker’s Mark, Old Forester, Wild Turkey, and Woodford Reserve, which is triple distilled in pot stills that were built in Scotland—a unique feature in the bourbon industry.

178. Prohibition in the United States

Left: Wayne Wheeler. Right: Andrew Volstead.

In June 1919, Andrew J. Volstead proposed a radical law that would shake up the American economy. Later that year, it passed in both the House and the Senate, despite a veto by President Woodrow Wilson, and on January 17, 1920, Prohibition came into effect, making it illegal to manufacture, sell, or transport intoxicating liquors (above 4.5 percent ABV), with a few exceptions, such as alcohol used for medicinal purposes or ceremonial wine for Mass.

Although Prohibition was referred to as the Volstead Act, the most prominent author of this piece of legislation was Wayne Wheeler, a Prohibitionist from Ohio who had been lobbying to make America dry since 1893.

179. What Were the Consequences of Prohibition?

Al Capone

Although President Herbert Hoover would dub Prohibition the “noble experiment,” its laws were consistently and purposefully ignored, culminating in a violent, deadly crime wave of unseen proportions that claimed thousands of lives.

Average Americans who wanted to enjoy an alcoholic beverage sometimes suffered health hazards from drinking illegally distilled bathtub gin called “rotgut,” which was manufactured in thousands of households with materials that were available but harmful to humans, like cleaning products or varnish. Tobacco and iodine were used as coloring agents to make the drink look more authentic. On the streets, wars were fought between the police and gangsters such as Al Capone over large quantities of smuggled whiskey. Not only were many civilians shot or murdered, but the repercussions on the American whiskey industry—which was almost completely destroyed—and the economy as a whole were grave. By the time Prohibition laws were repealed in 1933, the vast majority of distilleries had closed down for good.

“All I ever did was supply a demand that was pretty popular.”

Al Capone

180. What Role Did the Christian Temperance Movement Play in Prohibition?

The seed of Prohibition was planted fifty years earlier by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and its determined president, Frances Willard. In 1874 they initiated the first temperance wave in the United States, during which large groups of women took to the streets in organized demonstrations, holding saloons under siege by singing psalms and reading proclamation texts against the “demon alcohol.” Their efforts were certainly not unwarranted, what with many a sad example of alcoholism on the rise and men sometimes spending their entire week’s wages on liquor instead of food for their families. As a result, women and children experienced starvation, poor living conditions, and physical abuse.

Frances Willard

Frances Willard was born in Churchville, New York, in 1839. She moved with her family to Wisconsin, where at age ten she made a solemn pledge with her older sister: “To quench our thirst we’ll always bring Cold / water from the well or spring; / So here we pledge perpetual hate / To all that can intoxicate.”