Meet Mountain Wolf Woman

and Her People

When Mountain Wolf Woman was born in April of 1884, Wisconsin had been a state for only 36 years. Although Wisconsin was a young state, Mountain Wolf Woman’s people, the Ho-Chunk Nation, had lived in Wisconsin for hundreds, probably even thousands, of years. They live here still.

Mountain Wolf Woman grew up at a time when the Ho-Chunk way of living remained much like that of her ancestors. But other parts of her life were very different. This is the way it is for all families. Think of the many ways your life is both different from and the same as that of your grandparents and great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents.

To learn about Mountain Wolf Woman’s life in her own words, read Mountain Wolf Woman: Sister of Crashing Thunder; The Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian edited by Nancy Oestreich Lurie. Nancy Lurie is an anthropologist. She has studied the history and culture of the Ho-Chunk people.

Nancy Lurie

When Nancy Lurie was a college student, she was adopted by one of Mountain Wolf Woman’s relatives and became the niece of Mountain Wolf Woman. This kind of adoption among Indian people is a special form of friendship. As the friend becomes one of the family, the friend assumes the duties and privileges of all family members. These duties and privileges are determined by how one person is related to another. For example, aunts are expected to treat nieces and nephews with special generosity. So, when Nancy Lurie asked for Mountain Wolf Woman’s life story, she happily told it in her own language, and Lurie recorded it.

Lurie then turned to a Ho-Chunk friend, Frances Thundercloud, who speaks Ho-Chunk and English equally well. Frances Thundercloud translated Mountain Wolf Woman’s Ho-Chunk words into English. When you see quotes in this book, they are Mountain Wolf Woman’s words translated into English.

The first European to arrive in the western Great Lakes region was Jean Nicolet (jhan nik oh lay) in 1634. He was sent by the French government in Canada. But the French did not return to what is now Wisconsin for another 30 years because they were fighting the Iroquois (ear eh kwoy), Indian people who lived in eastern North America. When the French did travel back to Wisconsin in the 1660s, they came to set up missions and trading posts.

For generations before the Europeans’ arrival, Ho-Chunk families planted gardens of corn, beans, and squash, and they gathered many wild plants for food. They also caught fish and hunted animals with bows and arrows. They made their own clothes from tanned animal skins and built their own houses with bark or cattail mats.

There were no cameras when Jean Nicolet visited Wisconsin in the 1600s; this is what an artist nearly 300 years later imagined he looked like.

Each year, as the seasons came and went, groups of Ho-Chunk people moved to rivers, to woods, and to fields to get the foods and materials that they needed to live. But when the French arrived in North America, Ho-Chunk life began to change.

Ho-Chunk garden in winter

The Indians traded furs from animals they trapped for European goods such as kettles, knives, guns, cloth, and beads. Before the fur trade, the Ho-Chunk had been living in a large settlement in the Green Bay area. Once the French arrived, the Ho-Chunk began forming smaller villages. They spread across southwestern Wisconsin and northwestern Illinois in order to trap beaver and other animals along the many area rivers, including the Fox, Wisconsin, Rock, and Black.

The Ho-Chunk used European beads to decorate bags like this one from more recent times.

When the British took control of North America from the French in 1763, they continued trading with the Indians. And when the Americans took control from the British after the Revolutionary War, they also continued trading with the Indians. But then the American settlers wanted more than just trade. They wanted land. But different groups of Native people already lived all over the Americas. Many, of course, lived in what became the state of Wisconsin. How did the United States government deal with that problem?

More than 50 years before Mountain Wolf Woman was born, the United States government decided to move as many Indians as possible across the Mississippi River. Most tribes had little choice but to sign treaties to sell their land and move to other land set aside for them.

Members of the Ho-Chunk Nation were forced to give up their homeland in Wisconsin and Illinois in exchange for a reservation in Iowa. Then, in a series of treaties, the Ho-Chunk people were moved to Minnesota, South Dakota, and, finally, Nebraska. Today, about half of the Ho-Chunk people still live in Nebraska.

Imagine how you would feel if the government told your family that you had to move away from everything you knew and live in a land you had never seen! Some Ho-Chunk families refused to leave. They preferred to hide out in their beloved Wisconsin. Some who left Wisconsin returned later, including Mountain Wolf Woman’s family.

How many times were the Ho-Chunk forced to move?

Where Does the Name Ho-Chunk Come From?

The name Ho-Chunk can mean either “big fish” or “big voice.” This is big in the sense of important or original. You may have heard of the name Winnebago. This is what some people used to call the Ho-Chunk. Winnebago came from a Mesquakie (mes kwaw kee) Indian word meaning “people of the stinking water.” The Ho-Chunk used to live near marshy areas around Green Bay and the Fox River. These waters sometimes filled with very smelly dead fish and algae in the spring. Ho-Chunk is a name that comes from the Ho-Chunk language; in other words, this is a name they call themselves.

In 1874, 10 years before Mountain Wolf Woman was born, U.S. government officials put her family, along with other Ho-Chunk people, on a train. The train took them to Nebraska to live on the tribe’s reservation there. Mountain Wolf Woman’s mother, named Bends the Bough, later told her that some Ho-Chunk did not want to leave Wisconsin. But Bends the Bough said she was happy because she would see some of her relatives who had been moved earlier.

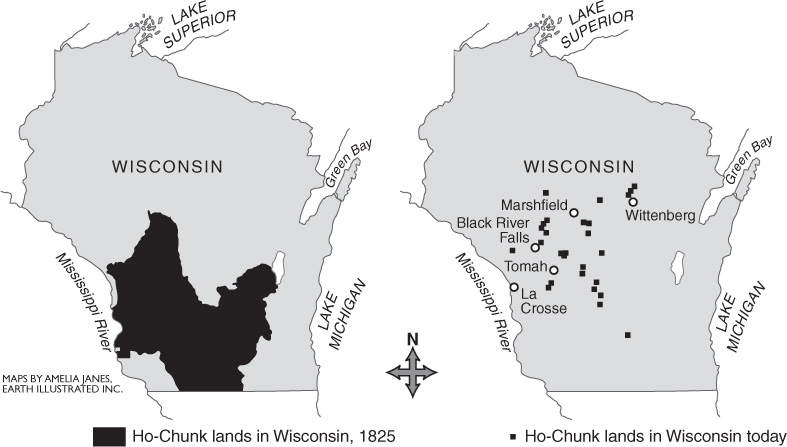

Compare the amount of land under Ho-Chunk control in 1825 and today. How do you think the U.S. government was successful in getting the land it wanted?

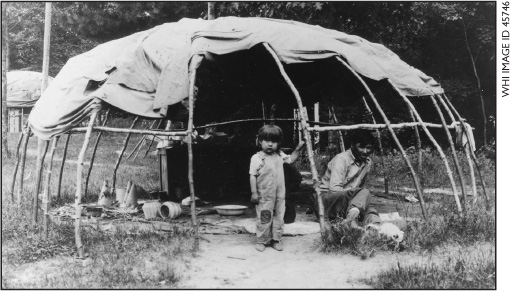

It was winter when Bends the Bough and her family arrived in Nebraska. They quickly built wigwams to keep warm. Wigwams were a handy type of house that could be built quickly in different sizes. Indian people in eastern North America had been building wigwams for thousands of years.

Like houses today, wigwams came in all sizes.

To build their wigwams, Mountain Wolf Woman’s family members cut down small saplings and stuck them into the ground to make round or oval shapes. Then they pulled the saplings down toward the middle and tied them together to form arches. They tied other saplings around the arches. After building these frames, they covered the outside with mats made from cattail plants or large pieces of elm or birch bark. Inside the wigwam, they covered the floor with mats made from bulrushes. These floor mats were harder to make. They also used these mats for decoration. A fireplace in the wigwam provided heat and light. A well-built wigwam was very comfortable.

But when the next spring arrived, many people were dying on the reservation in Nebraska. It was cold, and there were diseases and hunger. Somebody died almost every day! There were many burials and many tears. Bends the Bough was frightened for her family. She asked, “Why do we stay here? I am afraid because the people are all dying. Why do we not go back home?” So she and other family members decided to return to their homeland in Wisconsin. They moved to the Missouri River. There, they cut down big willow trees and made dugout canoes to prepare for their journey home.

Dugout canoes were made from a single log. Before the Indians got metal tools through the fur trade, they used fire to hollow out a large log. They burned the wood and then scraped away the charred wood with tools made from stone and shell. Later, after Indians began trade with Europeans, they used metal tools.

The dugout canoe has a long history in Wisconsin waters. Archaeologists from the Wisconsin Historical Society have preserved the remains of 2 dugout canoes—one is about 150 years old and the other is 1,800 years old!

Dugout canoe

Drawing of the 150-year-old dugout canoe preserved by archaeologists

To return home to Wisconsin, Mountain Wolf Woman’s family first paddled down the Missouri River to the “River’s Mouth Place,” where St. Louis, Missouri, is today. From River’s Mouth Place, they paddled up the Mississippi River. Finally, the family made it to Prairie du Chien and then to La Crosse. From La Crosse, they moved to Black River Falls.

How long do you think this dugout canoe trip took Mountain Wolf Woman’s family?

Have you ever floated down a river on an inner tube? You float with the current. Can you imagine paddling up the Mississippi River against the current of North America’s largest river? Think of how strong you’d have to be! Mountain Wolf Woman’s family must have really wanted to get home to Wisconsin.

The River’s Mouth Place

The Ho-Chunk called St. Louis “River’s Mouth Place” because it is there that the waters of the Missouri River empty into the Mississippi River, and this is called the Missouri’s “mouth.” But do you know why this place is called St. Louis today? This part of America was once owned by France. In 1764, a French fur trader established a trading post at this spot. He named it after his French king, Louis XV, and that is the name that most people have used since then.

After the 1874 attempt to remove all the Ho-Chunk from Wisconsin, the U.S. government gave up. The very next year, the government allowed the Ho-Chunk people who had returned to Wisconsin to live in their traditional homeland. Those who chose to return to Wisconsin could claim a homestead. Earlier, in 1862, the U.S. Congress had passed a law that allowed some people to get a homestead of 160 acres of land. In the 1870s and 1880s, Congress changed the law to include Indians. The new law was supposed to encourage them to live like non-Indian farmers.

But private ownership of land had not been part of Ho-Chunk life in the past. The Ho-Chunk people were used to planting large gardens on tribal lands each spring, and then they moved to different areas of their territory to get other types of foods throughout the year. Mountain Wolf Woman’s father was definitely not interested in owning any land because he was a member of a sky clan—the Thunder Clan. Mountain Wolf Woman remembered him saying, “I do not belong to the earth and I have no concern with land.”

Bends the Bough was also a member of a sky clan, the Eagle Clan. But she had her own ideas. She decided that in those changing times the family needed a place to call its own. She took a 40-acre homestead near Black River Falls. Mountain Wolf Woman’s father built a log cabin on the homestead. Mountain Wolf Woman’s family lived there during parts of the year, but often the family went away to get food or earn money.

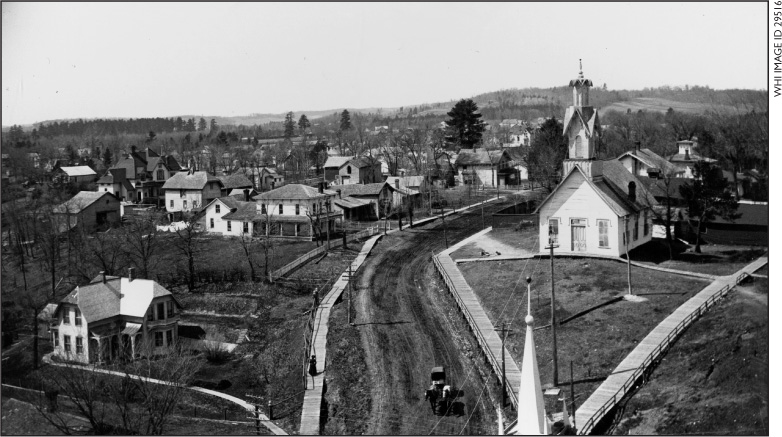

Black River Falls when Mountain Wolf Woman was a child

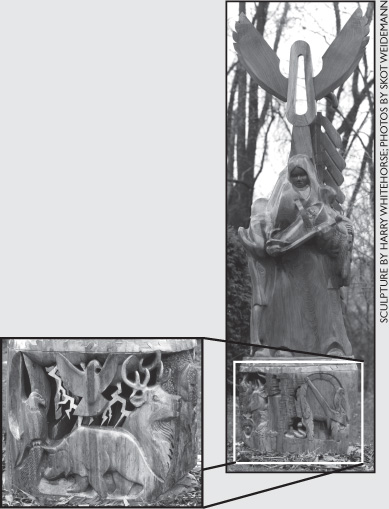

Like many other Indian nations, Ho-Chunk society is organized by clans. The clans in Ho-Chunk society, as in some other Indian cultures, are divided into at least 2 groups: those who are on earth and those who are above—the earth and sky.

The Ho-Chunk Family Tree by Ho-Chunk artist Harry Whitehorse shows the Ho-Chunk earth and sky clans. This sculpture is at Thoreau Elementary School in Madison, Wisconsin.

The largest Ho-Chunk sky clan is the Thunder Clan. The Eagle, Hawk, and Pigeon are also sky clans. The earth division includes the Bear Clan as well as the Water Spirit, Fish, Buffalo, Deer, Elk, Snake, and Wolf clans. Clans are named for the animal spirit ancestor. Each clan has its own origin story. The Ho-Chunk people believe that long ago, spiritual beings, who could take animal or human form, founded the clans.

Traditionally, different clans are responsible for different tasks. In the past, the Bear Clan kept order in the villages and made decisions about land. Peace chiefs came from the Thunder Clan. Today, clans are still important. The clans have responsibilities at feasts and ceremonies.