The Gift of a Name

Mountain Wolf Woman’s early childhood years were not recorded in photographs or videos as are those of many children today. But much was stored in her memories and in the memories of her family. Back in the 1880s, most people were born at home rather than in hospitals. From her family, she knew that she was born at her grandfather’s house at a place called East Fork River. It was early spring when she took her first breath, and her family was making maple sugar.

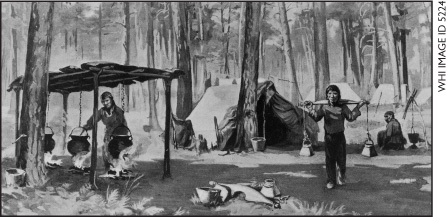

For many Indian people in Wisconsin, making maple sugar was part of their yearly round of activities. It was something they did every spring. Early in the season, when there was still snow, people set up camps out in the woods in groves of maple trees. They made cuts in the trees with axes and then put a piece of wood into the cut to guide the oozing sap into a bucket.

People spent many hours and days collecting buckets of sap. Then they poured the sap into large kettles. They boiled the sap in these large kettles for many, many hours until it began to granulate. Sugaring took a lot of hard work, but people looked forward to working with family and friends. Sugaring was also a time of celebration because everyone knew the cold days and nights of winter were almost over.

The buckets on these trees are collecting sap that will soon become maple sugar.

Sugaring was an important seasonal activity for many Wisconsin Indians.

Mountain Wolf Woman’s first memory was of a spring day sometime after her first birthday. She was with her mother, Bends the Bough, and her older sister White Thunder. Mother and daughters had come to a creek that they needed to cross, and there was no bridge. Her mother had been carrying Mountain Wolf Woman on her back in a cradleboard. When babies are in cradleboards, they face backward and can’t see where they are going. Mountain Wolf Woman started squirming. “I was restless,” she remembered. Bends the Bough took her off the board and carried her in a shawl on her back. From the shawl, Mountain Wolf Woman looked over her mother’s shoulder and saw what was happening. “I saw the water swirling swiftly.” She remembered seeing White Thunder carry the empty cradleboard across the creek while she held her skirt up to keep it from getting wet.

When she was older, Mountain Wolf Woman told her mother about this memory and asked her if it had really happened. Bends the Bough was amazed that she had such an early memory—it was considered a sign of great intelligence! When Mountain Wolf Woman shared this story with her niece, Nancy Lurie, she did not want to sound as though she was bragging. Mountain Wolf Woman added that her mother suggested that she probably remembered this early moment because she was so frightened by the swift running water. Think back. What is your first memory? Was it something scary or some other strong feeling?

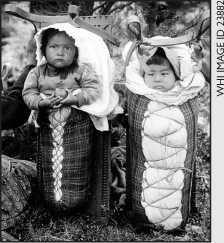

Cradleboards

All Ho-Chunk women kept their babies on cradleboards in the old days. The baby would be securely tied to a board with a footrest at one end and a hoop at the other end. The hoop was over the baby’s head. It protected the child if the board should fall. The cradleboard was an easy way to carry babies. The boards could also be stood upright on the ground so the babies could watch what their families were doing. Mothers often hung beads or other bright objects on the hoop to entertain the baby. The cradleboard also made it easier for mothers to do their tasks. While the babies were kept snug and warm on the cradleboards, their mothers’ hands were free to work.

Babies in cradleboards

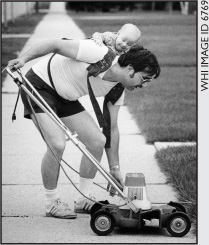

Parents still use baby carriers to make life easier.

Mountain Wolf Woman had several older sisters and brothers. It was the Ho-Chunk custom to have 2 names. One name was based on whether you were a girl or a boy and on the order of your birth in your family. Each person also had a ceremonial name that usually came from the clan. If a family had more than 4 girls or boys, they began to use names that were forms of the first 4 names. In Ho-Chunk families, if a fifth daughter was born, like Mountain Wolf Woman, that girl’s name was a form of the third girl’s name. The chart shows the different names of the children in Mountain Wolf Woman’s family.

Birth Order |

Ho-Chunk Name |

Ceremonial Name in Mountain Wolf Woman’s Family |

First Daughter |

Hínuga (hee noo gah) |

White Thunder |

First Son |

Kúnuga (koo noo gah) |

Crashing Thunder |

Second Daughter |

Wihaŋga (wee hah hag) |

Bald Eagle |

Second Son |

Hénaga (hay nah gah) |

Strikes Standing |

Third Daughter |

Hakśigaga (hahk see gah) |

No ceremonial name—this sister died very young. |

Third Son |

Hágaga (hah gah gah) |

Big Winnebago |

Fourth Daughter |

Hinákega (hee nah kay gah) |

Distant Flashes Standing |

Fifth Daughter |

Hakśigaxunuga (hahk see gah koo noo) |

Mountain Wolf Woman |

Mountain Wolf Woman got her ceremonial name when she was a little girl and was very, very sick. Bends the Bough was worried and did not know what to do. Finally, she asked an old woman named Wolf Woman to cure her daughter. Bends the Bough had great respect for the powers of old people. She told Wolf Woman, “I want my little girl to live. I give her to you. Whatever way you can make her live, she will be yours.”

Among the Ho-Chunk people, highly valued possessions are to be given away, not kept for oneself. Of course, little Hakśigaxunuga was not a possession but the daughter of Bends the Bough. Giving her daughter to Wolf Woman to cure was both a way to help her baby and a way to honor Wolf Woman with a gift.

Wolf Woman cried at the thought of such a precious gift. Wolf Woman said, “My life, let her use it. My grandchild, let her use my existence.” Then she gave the little child a holy name and predicted that she would live to be an old person. The name Wolf Woman gave the child was a Wolf Clan name—Xehaćiwiŋga (khay hah chee wee gah). And Xehaćiwiŋga got well! She lived to be an old person, just like Wolf Woman had said she would. Mountain Wolf Woman later said that the name Xehaćiwiŋga had a special meaning: “to make a home in a bluff or a mountain, as the wolf does, but in English I just say my name is Mountain Wolf Woman.”

Although many children in Wisconsin went to school in the late 1800s, most Ho-Chunk children learned what they needed to know from their families. Very early, Mountain Wolf Woman learned how to behave politely and properly with family members as well as strangers. She also learned the importance of the many spirits in the Ho-Chunk world. She learned about her duty to fast in order to get blessings from the spirits. She learned to always listen to her parents and never to be lazy. Mountain Wolf Woman understood that someday when she became a mother herself, she should never hit or scold her children. The Ho-Chunk women taught their daughters that hitting or scolding showed poor parenting.

Mountain Wolf Woman also spent many hours watching her mother and other women doing their work. She learned the things she would need to know to survive—how to garden, gather wild plants, and cook and preserve many kinds of food. She also learned how to build wigwams, prepare deer hides, make mats, weave baskets, and sew clothes.

These moccasins were made by Mountain Wolf Woman.

Ho-Chunk basket

Mountain Wolf Woman would have used thin strips of wood, like this piece, to weave baskets.

Ho-Chunk Spirits

The Ho-Chunk religion has many spirits, including Earthmaker, Thunder, Disease-Giver, Night Spirits, Sun, Moon, Day, Water Spirits, North Wind, South Wind, and Morning Star. The Ho-Chunk ask these spirits for blessings for good lives, health, and sometimes for “power”—the knowledge to heal and succeed.