Enslave the liberty of but one human being and the liberties of the world are put in peril.

—William Lloyd Garrison

SLAVERY INSIDE AMERICA’S BREADBASKET

ONE OF MY favorite snacks is almonds. I enjoy them plain, roasted, salted, slivered, and smoked. I take my cereal with almond milk and my toast with almond butter. I believe my hand cream even has almonds in it. Around 90 percent of the world’s almonds are grown in California, to the tune of $5.9 billion in production during the 2014–15 crop season. Indeed, almonds have quickly become California’s second largest agricultural commodity behind only dairy ($9.4 billion) and ahead of grapes ($5.2 billion), cattle ($3.7 billion), and berries ($2.5 billion). As with all of California’s agricultural products, almonds are grown in the state’s Central Valley, a 22,500 square mile region that spans from Bakersfield in the south to Redding in the north. The valley has a width of between sixty and eighty miles all the way between the two cities. It is an arid zone whose suitability for agricultural production was vastly enhanced in 1933 with the inception of the Central Valley Project. The project was created to provide irrigation and municipal water to the Central Valley by storing water in twenty reservoirs in northern California and distributing it across the valley through a vast series of canals and aqueducts. The project has not been without controversy, especially during California’s most recent drought. Almonds, in particular, have been at the center of a fervent water allocation feud because they require a substantial amount of water to produce. These important water allocation and preservation matters notwithstanding, the Central Valley Project has helped California become home to 76,400 farms with a total of 25.5 million acres, producing agricultural products worth $54 billion in 2015. California is not only the largest agricultural state in the United States but one of the most productive agricultural zones in the world. California is home to more than 99 percent of the U.S. stock of fourteen crops including grapes, figs, olives, pomegranates, pistachios, walnuts, and almonds. The state exports most of these products abroad as well, with the top foreign markets being the European Union, Canada, China, Japan, and Mexico.1 California may be best known for Hollywood and Silicon Valley, but its agricultural sector is an economic behemoth; as with all such behemoths, it requires a substantial amount of labor.

The Central Valley is one of the easiest places to research that I have explored. In most every respect, aside from air quality, it is the exact opposite of Nigeria. The region is safe and smoothly traversed thanks to Interstate 5 and State Route 99, which run roughly parallel, north to south, across the valley. Aside from lung-burning smog, a persistent layer of dust on my car, and an unpleasant bouquet of odors always worse at night, there were not many obstacles to my research in California. In fact, the agricultural region can be quite beautiful. The symmetry of perfectly parallel lines of almond trees in white bloom stretching for miles in every direction offers a soothing order that contrasts with the chaos and disarray I encountered in other regions. Each day I spent in the valley drew to a close with a splendid sunset, thanks paradoxically to the excessive levels of air pollution—horrible to breathe but brilliant for painting the last moments of the day with thick and enduring hues, red-blushed and enflamed.

It is no mystery that California’s agricultural sector is heavily reliant on low-wage migrant labor. During the peak of the agricultural season, thousands of migrant workers can be seen toiling away in the fields. Most of these workers travel to the United States from south of the border. A smaller number arrive from East Asia, primarily Thailand and China. The formal channel for migration and seasonal work in the agricultural sector is provided through H-2A visas,2 or the “guest worker” program. In addition, many thousands of migrants arrive each year and work on an irregular and undocumented basis. Whichever channel migrants use to enter the United States, labor trafficking is more prevalent in the country’s agricultural sector than I had anticipated. An individual is a victim of labor trafficking under U.S. and international law if he or she is (1) recruited, transported, transferred, or harbored (2) through force, fraud, or coercion (3) for the purpose of forced labor, slavery, or debt bondage. I met more than a thousand migrant workers in the Central Valley during the course of my research, and using highly restrictive criteria I documented the cases of 303 victims of labor trafficking. These victims can be divided into two categories: irregular migrants and H-2A visa seasonal guest workers. The labor trafficking victims I met told me extraordinary tales of exploitation and degradation similar to the experiences of agricultural slaves in the United States centuries ago. I cannot comprehend how, in some very important ways, so little has changed in the American agricultural labor system during the last two centuries, at least for the workers trafficked into its unforgiving clutches.

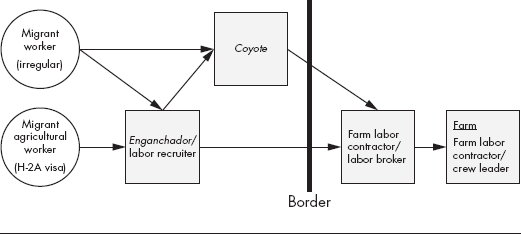

Figure 3.1 provides a basic picture of the labor supply chain from Latin America into the U.S. agricultural sector. The bottom of the chain is populated by the workers who migrate through regular (H-2A visas) or irregular channels into the United States. Both regular and irregular migrants often are recruited to travel to the United States for agricultural work by a labor recruiter called an enganchadores (literally, “down payment”). Many irregular migrants make their way north across the border without formal recruitment by engaging a coyote on their own. In most of the cases of irregular migration I documented, the coyotes facilitate the border crossing for the migrants because they know the best routes for entry on any given day that will minimize the chances of interception by the U.S. border patrol. Coyotes are usually in league with the enganchadors, and in many cases they are the same person.

FIGURE 3.1 Agricultural labor supply chain from Latin America to the United States

Once the migrants have crossed the border, they are handed off to a labor broker, also known as a farm labor contractor (FLC). This person might be part of a different network from the recruiters, or the entire process may be vertically integrated into one network. The FLC takes control of the migrant’s work life and manages the contracts, housing, wages, food, and other needs on behalf of the primary employer, the farm owner. Crew leaders on each farm manage the daily work routines and assignments of the workers on behalf of the FLC. Sometimes FLCs act as crew leaders. For the most part, farm owners have little contact with their migrant workers and are only vaguely aware of the particulars relating to them. The FLCs manage everything.

When labor trafficking occurs, it is almost always exacted by the FLCs or by the crew leaders. The coercive labor conditions forced on migrant workers by the FLCs are exacerbated and reinforced by debts accrued from fees charged by the enganchadores, who arrange the work opportunity, and by the coyotes, who arrange the border crossing (for irregular migrants). When I began my research, I suspected I would find forced labor to be more prevalent in the irregular migrant population of California’s agricultural sector due to the inherent vulnerability of their migration status; however, I was surprised to find that slavery and other exploitative conditions occurred almost equally in the population of regular migrants who arrived on H-2A visas. An exploration of some of the cases I documented reveals exactly how and why labor trafficking occurs in the U.S. agricultural system.

Labor Trafficking—The Irregular Migrant

It is surprisingly easy to find irregular migrants working on farms in California. I simply had to spend enough time forging local ties and trust in the worker communities, after which access was relatively straightforward. There was no need for security, bribes, or other complexities—just a translator. The most conducive locale for interviews was in the barracks, apartments, shacks, and other facilities where the workers slept at night. I met Enrique at one such worker residence in the summer of 2014. He was short, had an angular face, and hailed from southern Mexico, not far from the border with Guatemala. We sat in the shade under a tree outside the dormitory he shared with more than twenty other farm laborers, and he told me a harrowing tale of forced labor that stretched from his hometown right to your dining table:

I am from Chiapas. When I was nineteen years old, I left my parents and younger sister to travel to America for work. A man we call enganchador said he can arrange the work for a fee of 20,000 pesos [~$1,400]. My parents offered our land on loan for this fee. The enganchador took us to Nogales by bus, and a coyote met us there. His name was Antonio. We knew he worked for a cartel. I was nervous to cross the border with him. Antonio led us to a house, and he said we had to pay 10,000 pesos [~$700] to cross the border. After we cross, he said he can arrange farm work in California. I told him I already paid the enganchador to get the work, but Antonio said this was not his problem and I must pay him or return to my home. None of the men in the house had the money, so we had to work for the cartel until we earned enough. I do not want to discuss the work I did. Five months later Antonio took us across the border.

We walked for two hours and somewhere in the desert we came to a truck. Some men who were friends with Antonio drove us to an avocado farm in California. This was in 2009. From that time … what can I tell you … I have worked on five different farms … avocado, oranges, almonds, lettuce, and walnuts. Sometimes I am in the field picking the vegetables, or sometimes I am packing the boxes. In the beginning, I objected because the work was too difficult and I was not being paid what they promised, but the boss said if I complain he will make me deported. He said my parents’ land would be taken by the enganchador to repay the loan. I was very sad about the situation, but I had to keep working.

This place we live in here is not for humans. We sleep on dirty mattresses and share one toilet, all of us. We have no phone here, and we are far away from the city. If we want to go to the city, like if we want to go to the bank or buy supplies or maybe call our families, the boss charges $50 to drive us.

From dawn until dark we work. Usually we work six days a week. In the beginning, Antonio said we would earn $1,000 each month. I thought this was so much money I could not believe it. I thought I would send money to my family to help their circumstances. But it was a lie. I never earned this amount. Sometimes I am paid by the bucket; sometimes I am paid by the month. I never earned more than $500 in a month, and this is barely enough for my rent and my food. So I have nothing. After five years of work I have nothing.

I feel trapped because if I make problems I know I will be deported. I keep working because I hope one day I will go to a good farm where I will earn enough money to help my family. Until that day, at least I am alive. I am grateful for this, I know.

Please tell people there are thousands of Mexicans on these farms just like me. We share the same experience. We are forced to work like this because of poverty. I do not think the Americans realize where their food comes from. If they knew, they would not be happy.

Enrique was twenty-four years old when I met him, but like so many slaves I have documented, he looked old beyond his years. His body was worn, his face was haggard, his eyes were weary, and his hands were coarse and weathered like leather gloves. Life for him had been reduced to little more than a corrosive struggle to survive. I asked Enrique about physical ailments or injuries he had suffered, and he offered a wry smile: “You should ask which part of my body is not broken. That will be quicker.” Enrique’s vision was failing him, and he had chronic respiratory ailments. He suffered from heat exhaustion and frequent diarrhea. I asked if he ever received medical care, and he said the boss brought a doctor if workers were too sick to work or had a serious injury, but otherwise they had to toil through their ailments. They were charged $200 for the doctor’s visit and additional costs for any medicines they required, all of which compounded their debts. This arithmetic made them much less likely to ask for medical assistance, even if it was needed.

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Enrique about his time working for the cartel, but he said again that he did not want to discuss it. I did not push further; I knew all too well from other interviews I had conducted along the Mexican border with California and Texas what kind of “work” migrants were forced to do by the Sinaloa, Gulf, and Zetas cartels. From back-breaking day labor, to being drug mules, to burying dead bodies or dissolving them in acid, to forced prostitution, the cartels exploit migrants with medieval brutality. I could see in Enrique’s sallow eyes that he had probably been forced to perform acts that would likely haunt him for the rest of his life.

I documented eleven other workers at Enrique’s farm, all of whom told similar stories. Each one of them was ensnared in multiyear conditions of slavery. Eight were from Mexico, three from Guatemala, and one from El Salvador. Nine were recruited by enganchadores in their hometowns. All of them migrated north with the hope of earning enough income to send money back to their families, and all of them expressed a wish to return home one day with enough money to start a small business or get married and start a family. The same nine workers who were recruited by enganchadores had all offered family land as collateral for the up-front fees charged by the enganchadores. The threat of having their families evicted from their homes or land if the loans were not repaid was a powerful force of coercion that kept the victims working year after year in the hope that they would one day be free of the debt. As Rodrigo told me, “All we have is that land. If we lose it, my family will not survive.”

In addition to the recruitment fees charged by the enganchadores, Enrique and the other eleven workers had all been assessed additional fees from coyotes: some fees had to be worked off prior to crossing the border, and some fees were added to the fees charged by the enganchadores. In the latter cases, the enganchadores and the coyote were usually the same person or part of the same network. Only two of the eleven workers I documented at Enrique’s worker residence had been able to send small amounts of money home across the years (through Western Union). For the most part, they worked day and night just to survive, with no opportunity to leave, do other work, or return home. Their movements and employment options were completely restricted, and they had no way to break free of this chokehold. In truth, I could tell little difference between these men and prison laborers other than that physical incarceration is more obvious for prisoners, and their living conditions might actually be better.

During the course of my research, I documented a total of 175 labor trafficking victims who worked in California’s Central Valley by way of irregular migration channels. Their journeys were fraught with peril, debt, and servitude. They were exploited at almost every step in the process, from recruitment by enganchadores, to border crossing with cartels and coyotes, to their work in the agricultural sector in California. Although my research was restricted to the state of California, cases of irregular migrant agricultural workers who end up in forced labor conditions have been documented across the United States in Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, Colorado, Washington, Maine, Nebraska, and Idaho. Almost anywhere agricultural products are grown, you can find these exploited workers if you look long enough. Another interesting fact that emerged from my research is that almost half (84 cases) of the irregular migrants I documented in forced labor on farms in California were not recruited by an enganchador. Instead, they made a decision to migrate north without a job opportunity awaiting them and found their way across the border with the help of a coyote. Fees for crossing the border in these cases skewed higher, ranging from $1,000 to $2,000. For these individuals, the forced labor exploitation typically began at the coyote stage, often in the form of harsh servitude for a cartel such as Enrique had endured. In other cases, the exploitation commenced after arrival in the United States when the migrant liaised with an FLC or other labor recruiter, who then exploited the vulnerability inherent to their irregular status to coerce them into forced labor. In every case of agricultural labor trafficking I documented in California, the FLC or other labor recruiter was reported to me to be directly involved in the exploitation, be it with irregular or regular migrants.

Precise estimates for the number of irregular migrant labor slaves being exploited in the U.S. agricultural sector are difficult to calculate, but there are easily tens of thousands of such individuals toiling in servitude in plain sight. I cannot stress enough just how accessible these slaves are; they were right there, being exploited in broad daylight. I had but to build trust and start speaking with them to document their cases. There were no guards, barriers, threats, or other blockades. One by one I documented these slaves, and with more time and resources I could have easily documented hundreds more—the broken bodies that pick, process, package, and supply us with the food we eat every day. They endure unimaginable perils to migrate to the United States in search of a decent life, only to find slavery and degradation instead. No matter the circumstances through which an individual enters this country, he or she never deserves to be a slave. That is, however, exactly what many migrants find, whether they enter through irregular channels or with pristine paperwork.

One of the last irregular migrant slaves I documented was a man named Mateo. He was working on a berry farm not far from Redding, California. In a desperate bid to escape poverty in El Salvador, he ventured north, managed to cross the border into the United States, and connected with a labor recruiter known to other people from his hometown. After three years of exacting forced labor and a complete inability to leave the farm despite a pressing desire to do so, he had been paid roughly $6,180 in wages (~$171 per month), sending home as much as he could. With a very gentle, accepting voice, he said to me, “We are the people no one wants, but everyone needs.” The wisdom of his words astounded me. When the powerful do not want the people they need, they invariably find ways to subjugate, debase, and diminish them. That is the caustic formula that drives the culture of slavery. The millions like Mateo are discarded, unprotected, and exploited by the societies that cannot seem to function without them but do not ever want to recognize them as equally human. These migrants do not brave the immeasurable hazards of irregular migration so that they can take something from us; they do so because we pull them here, into a system that operates on levels of misery we would not accept for “our” people but are all too content to accept on Mateo’s behalf. Some justify his exploitation by citing his offense against migration laws (which I reject), but migrants who abide by those same laws are often just as exploited as those who are unable to do so.

Labor Trafficking—The H-2A Guest Worker

Those who travel to the United States through an H-2A visa can be just as vulnerable to slavery as those who arrive without visas. Their push to migrate is derived from the same motivation—the dream of elevating their families or desperation to escape violent and insecure environments. For those who migrate through regular channels, the perceived up-front risks are much less. They are entering the United States through legitimate means and believe they will have a wage-paying job waiting for them. Nonetheless, many of these individuals end up as labor trafficking victims, and for them the dynamics are similar to those of irregular migrants. Paradoxically the H-2A program offers additional distinctive avenues for servitude that are often exploited by the very people providing the visas—namely, the FLCs.

An H-2A visa allows a foreign national to enter the United States as a guest worker for temporary or seasonal agricultural work. The program was specifically established to provide a means for agricultural employers with a shortage of farmworkers to bring foreign workers into the United States on a temporary basis to meet short-term labor needs. It is difficult to know exactly how many H-2A agricultural workers there are in the United States in any given year, but the number has been increasing every year for the past decade, with estimates of H-2A workers in the United States in 2016 ranging from 100,000 to 130,000.3 These workers are supposed to be covered by most U.S. wage and labor laws. They also are meant to be provided with free housing for the duration of their contracts, the same health and safety protections as U.S. citizens performing the same work, workers’ compensation benefits for medical costs and time off work for medical reasons, free legal services relating to their employment under the visa program, and reimbursement of the full costs of their travel to the job site once they have completed 50 percent of their contract period. Despite these important protections stipulated in the H-2A visa program, I found that forced labor was often present among the guest workers in California’s Central Valley. The primary reason for coercing a guest worker into forced labor appears to be related to the cumbersome requirements on the employer for bringing in migrants under the program, which makes it desirable to keep the workers for more than one season rather than reapplying each year. A young man named Felipe, whom I met at a farm near Bakersfield, explained his situation:

There is a recruiter in Mexico who works with the brokers in California to make the H-2A visas for us. His name is Luis. The cost is 30,000 pesos [$2,000] to arrange the visa and transportation to the farm in the United States with guaranteed work for the season. Luis says we will be paid 150,000 pesos [$10,000] for the season if we work hard. Most of us did not have money for the fees, so Luis said the fees can be deducted from our wages. He said that 10,000 pesos [$667] was for the cost of transporting us to California and that we would be reimbursed this amount after we finished our contract. I received my documents, and we came to Calexico in a bus where a man named Fernando drove us to a farm. He took us to these apartments and said we would rent these from the broker. Fernando took our visas and said he will return them at the end of the season.

I worked on a farm in Mexico before I came here, so I was familiar with the work. We work on the soil and do construction, and when it is time we pick the vegetables by hand. Fernando did not give me a wage the first three months. He gave me a pay slip in English, so I could not understand it. When I asked him why there was no money left for me, he said it was because of the deductions for my transportation from Mexico. He said they also took money for the apartment, food, transportation to the farm, and also for a lawyer to process our visa. I asked him to show me my wages and these expenses in Spanish, but he did not. At the fourth month, I received a wage of $200. It seemed too little, so I asked the crew leader to explain the wage to me. He said they had to do repairs on one of the trucks they used to transport us, so this was deducted from our wages. I did not think this was fair. They said if I did not like being at the farm, they can send me back to Mexico. I did not want to do this because I have no money after all this time.

Our crew leader is very strict. They have beaten some of the workers, including me. If we ask too many questions, he says we should be happy we have a job. He says we are lucky and there are lots of people who can take our place.

We are not allowed to leave the farm during the day, and we have to stay in our apartment at night. The apartment is crowded and it is not in a good condition. It is very hot so we asked for fans. They brought two fans and charged us for them. There are rats in the apartment. The only good thing I can say is that we have enough food to eat.

At the end of the first season, they told us that if we want to stay, they can help us. The broker said he would keep our documents and we could stay on the farm, and we can earn $400 or $500 each month. This is not as much money as I hoped, but it is more than I can earn in Mexico. I have been on the farm for four years. I would like to do other work where I can earn more, but if I leave, I will be deported for staying past my visa. Now I think I might never leave this place.

That is my situation. I know some workers who have a much worse situation. These days I can send some money to my family. They charge us $40 to take us to the money transfer office, but it is worth it.

Felipe’s situation was complex, but he was clearly in a condition of forced labor at the farm, and I believe he had been recruited and trafficked from Mexico for that purpose. His documents were confiscated on arrival, and his freedom of movement and employment were completely restricted. He worked for paltry wages (about $1.50 per hour) in a system of unfair and excessive wage deductions and the ever-present threat of deportation. Even if he wanted to leave the unfavorable employment situation and search for another option while his H-2A visa was legitimate, the visa stipulates that it is only valid as long as he works for the employer listed on it, so he never really had an alternative. He was resigned to his situation and was trying to see the best in it. The only time his face showed any signs of life was when he told me how he sent money to his family, however little it might be. This seemed to be the primary driving force that kept him going. Otherwise, he knew that he was being exploited each day as he slogged on the farm in harsh circumstances. When I asked him about his plans, he said he expected to work on the farm until he died … or maybe one day he might try to run away and return to Mexico.

Other guest workers I met throughout the Central Valley told me similar stories. They had all been recruited by labor brokers near their homes in Mexico. Interestingly, 42 of the 128 labor trafficking victims in the guest worker program I documented found their jobs through websites. All 128 had their contracts and documents confiscated for the duration of the season. A total of 73 of the 128 victims stayed past their initial visa terms and were in the midst of multiyear forced labor. Of the remaining 55 cases, 42 of them were exploited in forced labor conditions during their first guest worker term in the United States, and the remainder were exploited in forced labor conditions during subsequent years in the United States. Wage deductions were rampant, especially for the initial transportation fees. These fees were either overstated when linked to a wage deduction, or they were not reimbursed when the worker paid them out of pocket, even though the guest worker program stipulates that they should be reimbursed in full after the worker has completed 50 percent of his contract. The fees the workers were charged by labor brokers or FLCs for the arrangements made under the H-2A program (transport, documents, etc.) ranged from $2,000 to $5,500 in the cases I documented. The higher fees were typically for workers from farther south in Central America, and even a few from the Caribbean. For those workers who ventured back and forth under the visa program across different seasons, the fact that they were not allowed to switch employers during their work periods was used by the more unscrupulous FLCs to exploit them in conditions of slavery. Physical abuse was common. Illness and injury were also the norm, including heat stroke, respiratory ailments, vision impairment, urinary tract infections, lacerations, and broken bones. Every individual I documented lived in housing provided by the FLCs that was quite a distance from the nearest city. The housing areas were the only venues in which I was able to interview the workers, typically during the night hours, or on Sunday, which was their only day off. The houses and apartments I saw were in terrible condition. Paint was peeling, toilet and kitchen facilities were insufficient, and there was no air conditioning, which made sleep very difficult during the stifling summer months in the Central Valley. The workers were all given enough food to eat in terms of calories, but the quality and nutritional value was quite poor (usually canned or processed bulk foods). It is a painful irony that these farmworkers live and work in the midst of one of the most plentiful agricultural zones in the world, yet they are forced to subsist on substandard and processed foods. As one worker, Juan, whom I documented at a farm near Fresno, told me, “In Mexico we can eat the food from the farm. Here we cannot touch our mouths to it.”

Aside from obvious greed, I was perplexed as to why farm owners or their FLCs would resort to extracting slavery under the H-2A program. Their primary motivation appeared to be to avoid the complications of going through the tedious application process year after year, but it seemed to me that attorneys could handle this without too much expense, especially relative to the revenue streams the farms enjoyed. In an effort to explore this question further, I spoke to Douglas, a man who owned more than 1,100 acres of farmland in the Central Valley. He explained exactly why some farms in the valley resort to exploitative tactics.

THE H-2A GUEST WORKER PROGRAM: A CLOSER LOOK

Douglas’s land is green-striped, with thousands of parallel rows of almond and pistachio trees stretching beyond the horizon not far from the city of Lost Hills, California. He inherited the land from his father and takes great pride in his stewardship of the portion of the earth allotted to him. Douglas invited me to his home, and we sat on his covered patio under ceiling fans. He was a fourth-generation farmer in the Central Valley and an avid supporter of the H-2A program. He described the process and procedures of the program in detail:

First off, we have to apply at least 45 days before we want the worker to receive the visa. I also have to try to recruit U.S. workers with newspaper and radio advertising and first give the job to any U.S. citizen who applies before I can give it to an alien. Americans don’t take the jobs, so that part is not an issue; it’s just a hassle really. The filing fee is $320 per application. For each alien I hire, I have to pay another fee of $10 up to a hundred workers. Those are the fees, so all in all it’s pretty cheap from my perspective. Each visa I get is valid to 364 days. That covers one full season of work. The lawyers handle the rest, but they aren’t too expensive either. They have to file petitions every year with the Department of Labor that we certify there are not enough U.S. workers who are willing and able to do the work, and that if aliens are hired it will not have a negative impact on the wages of U.S. workers in the area. Let me tell you point blank that part is bullshit. They are just covering their asses. Even though I pay the same wages to my aliens as I do to my U.S. workers, most farms out here don’t, and that brings wages down without a doubt. No one with a straight face who knows what they’re talking about will tell you otherwise. Wages go down because of all the alien workers from across the border. That’s the way it works, and that’s the way people want it to work. Yeah, it means U.S. citizens are less likely to take the work, which means we need more aliens. It’s a system, and everybody knows it. They count on it. That’s been the way out here for a long time, and that’s how it’ll be long after I’m gone.

I asked Douglas whether there were any efforts by the authorities to ensure the guest workers receive the same wages as U.S. workers.

“What did I just tell you? They don’t want them to get the same wages. It’s all in the paperwork. We keep logs of wages and all that information is in our filings, but people can file whatever they want and nobody is going to ask past that. Even if they did, the government doesn’t have the resources to audit all those records. You can forget about that.”

“What about wage deductions, for things that are supposed to be provided to the workers under the program for free, like housing or medical care?” I asked.

“A lot of the farms exploit the aliens. Let’s just get that straight. They know nobody is going to do anything about it.”

“I’ve also seen a number of cases where the workers are charged large up-front fees and go into debt trying to pay them back, or they have these fees deducted from their wages, far in excess of what they should be.”

“The rules of the visa say that recruitment fees are our responsibility, but it also says that we can charge ‘reasonable’ fees to the worker for help in arranging their documents and transportation. That’s where the aliens get hosed. The brokers charge them these crazy fees and deduct from the wages whatever they want. What are those aliens going to do?”

I talked to Douglas about some of the other cases I had documented in which workers had been told they could stay past their visas to earn real money because most of the first year’s wages had been deducted for fees. Douglas said this situation happens often and is part of the system in the valley. I next asked him about housing and pointed out that many of the worker domiciles I had seen were in terrible condition.

“Housing has to meet OSHA standards,” Douglas replied, “They do on my farms. I can have someone show you.”

“You mean like having a minimum number of cubic feet per person?”

“Yeah, it’s all regulated—the number of people per toilet and per shower, hot water, ventilation—they go into detail on that stuff.”

“But nobody seems to be monitoring that this is actually being done.”

“Honestly, if it’s done like the law says, the aliens would be better off than U.S. workers. I think that’s why some people feel it’s okay to slack on the rules.”

After speaking at length with Douglas about the specifics of how his farm operates, I asked him what his primary concerns were about the farming system in general in the Central Valley. Without a moment’s hesitation he replied, “Water.”

“You mean the drought?”

“I mean, we’re running out, and it’s no joke.”

I had seen billboards on highway 99 and the I-5 freeway throughout the Central Valley pitching both sides of the water debate—conservationists pointing out how much water it takes to produce one pound of almonds or an ounce of cheese or eight ounces of beef, and other billboards blasting politicians for mismanaging the state’s water supply and being more worried about preserving indigenous fish stocks then supporting local farmers. Douglas had firm opinions on the matter.

People are upset about the almonds around here. It’s true they suck water all year round, unlike other crops, but the fact is one mature almond tree can produce 2,500 pounds of almonds in a year, and right now almonds wholesale at $3.50 a pound, so you do the math and tell me that a farmer doesn’t have the right to plant more almond trees if he wants to. Hell, I enjoy a good steak as much as any man, but you can bet beef takes just as much water as almonds, but you don’t hear anyone talking about giving up steaks to save our water supply.

I was curious about the comparison, so I asked Douglas just how much water beef requires, and he said anywhere between 800 to 900 gallons of water for one eight-ounce steak. The ratio astounded me. Douglas explained further that eight ounces of chicken requires closer to 150 gallons of water, and eight ounces of eggs less than 100 gallons. As for almonds, they require around 100 gallons per ounce, roughly the same as beef. The statistics Douglas shared made me appreciate more clearly just how water-intensive the agricultural sector was. I thought that being a vegetarian might have absolved me from some of the water wastage, but my predilection for nuts made me just as culpable.

Douglas had a lot more to say about California’s water supply. I listened to his concerns, then returned the conversation to my research into labor issues and asked him if there was anything else about the farm labor system in California that he thought was a source of the abuses.

“There is one other major problem I would point out,” Douglas said. “Until a few years ago, the FLCs were paid by a percentage of the worker wages. You can bet this led to a lot of abuse because the corrupt ones would take more than they were supposed to. So the state switched to a fixed fee per worker recruited. I think they thought this would solve the wage problems, but it made things worse.”

“How so?” I asked.

“Now the FLCs recruit more workers than we need just to get those fees, and a lot of those aliens just get sent back with debts from the fees they paid the recruiters, or they sit around here doing nothing, earning nothing. That’s when they end up in bad situations.”

Douglas went on to explain that there is no annual limit on the number of H-2A visas that can be granted by the government, and this feeds right into the racket of exploitative brokers and FLCs recruiting more workers than are needed and pocketing the large, up-front fees they charge for arranging the visas. Because many migrants have accrued huge debts to make it to the United States, they are willing to accept almost any work opportunity they are offered to try to repay their debts, and those offers often involve slavery.

My conversation with Douglas helped me understand the inner workings, and failings, of the system of labor recruitment in the Central Valley. He identified many of the crucial gaps and loopholes that allow labor exploitation and slavery to persist in California’s agricultural sector: a lack of oversight and auditing of wage records; a lack of adherence to the policies of the guest worker program; H-2A policies that promote exploitation; and a system that, according to Douglas, thrives on low-wage, expendable migrant labor and hence is not really motivated to do anything about the abuses.

Toward the end of our conversation, Douglas spent a few minutes talking about the history of the Central Valley. He felt very connected to the land because of his ancestry, and I could see that he tried to manage his farm in an honest way. Douglas mentioned a few other farms belonging to friends that I could visit, which I managed to do. I thanked him for his time, and as I got up to leave he said, “I have to be honest. Sometimes my crew may take shortcuts. I don’t condone it, but I know it happens.”

FLCS

Everything I learned from the farmworkers and farm owners throughout the Central Valley made it clear to me how, why, and where forced labor occurs. In virtually all cases, the FLCs were involved, so I set myself to the task of learning more about them. The California Department of Industrial Relations defines an FLC as:

Any person/legal entity who, for a fee, employs people to perform work connected to the production of farm products to, for, or under the direction of a third person, or any person/legal entity who recruits, supplies, or hires workers on behalf of someone engaged in the production of farm products and, for a fee, provides board, lodging, or transportation for those workers, or supervises, times, checks, counts, weighs, or otherwise directs or measures their work, or disburses wage payments to these persons.4

The California Labor Code section 1683 requires that anyone acting as an FLC must be licensed by the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement and must be certified at the federal level by the U.S. Department of Labor. As of May, 2016, there were 350 FLCs registered in California, out of a total 810 FLCs registered across the United States.5 This means that roughly 43 percent of all licensed FLCs in the United States are in California. The average wage of an FLC in California is $60,040, which is roughly three times that of a properly paid farmworker, and more than eleven times the average wages received by the labor trafficking victims I documented in California’s agricultural sector. FLCs in California come in all sizes, from one-man operations to large companies such as Valley Pride, Inc. and Tara Picking, which have more than one thousand employees between them. The majority, however, are small operations of one to three people. Many of these one-man operations were started by former farmworkers.

I began my investigations into California’s FLCs with the state’s Farm Labor Contractor Association. Only willing to speak off the record, a high-level member of the staff described the duties of the association to me and the issues it faces with improper behavior with some of the licensed FLCs. The first thing this official told me (let’s call him “Jim”) is, “Most of the problems with improper payment of wages or treatment of workers happen with FLCs that are not licensed.” Jim assured me that the licensed FLCs go through a rigorous licensing process, including nine hours of coursework, a written examination, and extensive training on sexual harassment, which Jim said was one of the biggest problems among California’s FLCs. The other problem he deals with regularly is “the lack of enforcement of OSHA heat stress regulations,” which leads to numerous cases of heat stroke and even deaths each year.

I asked Jim whether any efforts were made to crack down on FLCs that operate without a license, if this is in fact where most of the abuses occur.

“We don’t have as many inspectors as we need,” Jim replied. “That’s because of budget cuts from the state. But if we do find an FLC operating without a license, they can be fined up to $10,000.”

“Only up to $10,000?”

“That’s the maximum fine.”

I pointed out to Jim that if exploitative FLCs can make ten or twenty times per year the amount of the fine by putting workers in forced labor, then the fine is not terribly deterrent.

“That’s the law,” Jim said.

“What about the recent change in FLC compensation from being paid a percentage of the worker’s wages to being paid a one-time fee for each worker recruited? Won’t this lead to overrecruitment, which leaves a lot of workers here with no job or income, which ultimately ends up with them being exploited as they try to find a way to repay all the up-front fees they were charged?”

Jim needed me to repeat the question, then break it down into parts, but he eventually told me that there can be abuses either way the FLCs are paid. I asked Jim if he could think of any other means of FLC compensation that might help minimize abuses, but he did not have any ideas. Neither did I, aside from better monitoring.

Jim’s overall perspective was that the California Farm Labor Contractor Association does as good a job as possible at monitoring FLCs given its resource constraints, and that most of the abuses take place with the nonlicensed FLCs. He conceded that if a licensed FLC were shorting workers on wages or putting them in substandard housing or exacting conditions akin to slavery, there were simply not enough inspectors in the state to do much about it. The federal government also has a role to play because FLCs must receive federal registration to operate. At the federal level, FLCs are monitored by the Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, which can revoke their licenses for infractions. To date, a total of 672 FLCs across the United States have had their registrations revoked; almost all of them were individual operators.6 There are, however, bound to be numerous duplicate entries in the list of revoked FLCs because people often reregister with a new name or use a family member’s name. The lack of accountability in the system at the federal and state levels frustrated me, especially because it was clear that this was a major factor in allowing abuses to take place. The lack of accountability was partially a function of insufficient enforcement, but even more a function of the absence of visibility and liability for farm owners relating to the actions of their FLCs. If farm owners faced serious and tangible liability for worker exploitation, the system would surely have far fewer abuses.

As I pieced together the labor supply chain in the Central Valley, it became clear to me that FLCs in essence function the same way for American farm owners as foreign manufacturers (like Foxconn) do for U.S.-based companies (such as Apple). They are a means of outsourcing the recruitment, treatment, and management of labor that severs legal liability between the company and the conditions under which the workers live and work. Farm owners can point a finger to the FLC and claim ignorance of any abuses that may be committed. They can say they do as much as possible to require decent working conditions, just as a U.S. multinational can claim the same for workers they use through subcontractors abroad, but that the ultimate responsibility lies with the FLC or labor subcontractor. In the case of California’s agricultural sector, FLCs serve as intermediaries that provide the owner with the cheap labor pool they want, while simultaneously severing the legal, but not the ethical or moral, liabilities associated with the treatment of those workers.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the FLC system in California reminded me quite clearly of the jamadar system of labor recruiting in India that also severs the employer’s liability for labor abuses. In this system, labor recruiters also operate in the same country as their employers, which one would hope might tighten the link of vicarious liability between owner and worker via the subcontractor. However, in Bonded Labor I outlined exactly how the jamadar system of labor recruitment in South Asia ends up being a primary driver of slavelike labor conditions in numerous sectors across the region’s informal economy, thanks to the absence of vicarious liability.7 The FLC system in the United States works exactly the same way as the jamadar system in India: an employer has labor needs and outsources fulfillment and management of the laborers to a subcontractor (the FLC or jamadar). The FLC or jamadar recruits workers, transports them to the worksite, manages their working conditions and wages, and in many cases exploits the imbalance of power between them and the workers to exact slave labor. The lack of vicarious liability between the primary employer and the FLC or jamadar means that the employer is not legally responsible for abuses committed by the contractors.

This lack of liability leads to a key thesis about global labor trafficking:

Systems that sever liability between primary employers and migrant laborers through labor subcontractors are responsible for a significant proportion of slavery and child labor in migrant worker populations around the world.

This system must change, either through a direct legal relationship between the primary employer and the laborer or through the extension of the principle of vicarious liability to include the relationship between primary employer and labor subcontractor. In Bonded Labor, I call for either new statutes or strategic litigation to extend liability from the jamadar to the employer through a broadening of the reach of vicarious liability, and I believe the exact same needs to be accomplished in the United States vis-à-vis FLCs and the farm owners who engage them. Doing so would lead to a considerable decrease in abuses because farm owners would have a vested interest in maintaining compliance with labor laws and in ensuring that they work with fully licensed FLCs, if in fact most abuses are committed by the unlicensed ones.

My efforts to conduct interviews with FLCs were not as productive as I had hoped. I managed to have conversations with just three small-sized FLCs in California, and they largely corroborated what I already knew. They were fully licensed, and each maintained that they adhered to all stipulations of the H-2A visa program. Of interest, one of the FLCs told me, “There are a lot more unlicensed contractors out here than people realize. That’s where you have the problems.” The FLCs also told me that when abuses occur it is at the hands of the crew leaders who manage the workers directly at the farms and not the FLCs. Many crew leaders are former farmworkers who have climbed up the ranks. Although they often are the same person/entity as the FLC, they also may be hired by FLCs (as was the case with the three FLCs I interviewed) to manage labor on their behalf. The FLCs stressed that unlicensed FLCs, in particular, relied on crew leaders that they did not monitor at all. This was yet another level of subcontracting complexity to explore, but I was slowly narrowing the scope of where the abuses in California’s agricultural labor supply chain were occurring, from farm owners, to (mostly) unlicensed FLCs, to (possibly) the crew leaders. I spoke to them next.

CREW LEADERS

After several forays and enquiries, and quite a bit of time building trust, I had several conversations with crew leaders on farms where I had documented cases of labor trafficking. The crew leaders had significant latitude in how they managed the migrant workers. No one was regularly monitoring them as long as the workers were productive. If the crew leaders wanted to (or were instructed to) squeeze labor costs, they knew exactly how to do it, and how to get away with it. The migrant workers were vulnerable, frightened, and lacked any will to think seriously about pursuing an alternative employment opportunity or enforcing their rights, and few even knew what their rights were. The conversations I had with crew leaders were at farms in the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys. Nine out of the eleven crew leaders I interviewed were Mexican. There were strong racial and class divisions between the crew leaders and the farmworkers they managed. The Mexican crew leaders saw themselves as a higher class of individual than the migrants from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, and they also saw themselves as superior to the other Mexican workers, even though most of them were once in the same position themselves. It was a similar dynamic to what I documented with gharwalis in India or madams in Nigeria, who were all once “lowly” prostitutes but in their new roles of power took on airs of superiority, having survived long enough (and been trusted enough) to be promoted to becoming exploiters themselves. These new positions came with an elevation in status, power, and self-worth that most of the crew leaders, madams, and gharwalis reinforced at every occasion.

The most interesting conversation I had with a crew leader was with a heavily opinionated man named Elias on a walnut farm not far from Jacinto, California. In a matter-of-fact tone, Elias outlined his job responsibilities: “I handle the farmworkers. I keep them housed and fed. I transport them from the apartments to the farm. I drive around the farm most of the day. I make sure the farm runs smooth. If something breaks down, I fix it.”

I asked Elias about some of the cases of labor exploitation I had documented. He responded firmly: “You don’t understand how things work here until you live out here for a whole season on these farms. This is good work for the migrants. Most of them are hard workers. They know how lucky they are to be here because they have nothing back in Mexico. America gives them opportunities, but not all of them have been trained to work hard the way we have. We have to be firm with the workers who are not as experienced, but that’s only to help them be better.”

Elias’ response made me feel as if I were speaking to Love (the madam) back in Nigeria. Like her, Elias did not feel that he was abusing or exploiting the workers under his charge; rather, he was giving them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to earn a better life. According to him, many of the migrants did not know how to work hard (i.e., they were lazy), so he had to be firm with them and train them to work harder so that they could succeed in the opportunities he was giving them. What he called “training” I called “slavery,” and that is the essential perceptual difference responsible for much of the servile labor exploitation around the world. I asked Elias what he meant by having to be “firm” with the workers.

“A lot of them want to run away because the work is too hard,” he replied. “They think they can find some other job where they don’t have to work.”

“Do you really feel they are all trying to run off and cheat you?” I asked.

“They’re gone the minute you turn your back.”

“So you feel you have to keep them under guard or keep their documents so that they don’t run away, that’s what you’re saying?”

“In some cases.”

“I can’t say that’s consistent with what I have seen, but I suppose you would know better than I would.”

Elias looked at me with a wry smile, “What do you think you’ve seen?”

“I’ve seen hard-working men who are put in situations of severe exploitation, not paid the wages they were promised, charged excessive fees for rent and food, forced to live in subhuman conditions, sometimes charged excessive fees to arrange their visas or jobs in this country, and they end up trying to work off these debts for years, with little income to show for it. That’s what I’ve seen.”

“If that’s what people are telling you, they’re lying.”

“Why would they lie?” I asked.

“Because they think you’ll help them.”

“Why would they need my help?”

“Because they don’t realize how much better they have it here than back in their homes.”

“I don’t think they see it that way.”

“They’re better off than I am too.”

“I don’t think they see it that way either.”

“That’s because you don’t know how things really work out here.”

“So tell me.”

“No, you tell me, how do you think they work?”

I thought about it for a moment then replied, “Well, I think compared to you, the workers would say the fact that you can come and go freely and are able to change jobs if you want to makes your situation much better, not to mention that you are probably paid the wages you are promised.”

“What makes you think I can just come and go as I please?” Elias asked.

“Can’t you?”

“Where am I going? I have bills to pay. I can’t leave this job any more than they can leave theirs.”

I tried as patiently as possible to explain to Elias that although his options may be constrained due to his financial situation or the lack of alternatives for someone with his skill set, no one was restraining him or preventing him from leaving with threats of deportation if he wanted to leave.

“No difference,” he curtly replied.

“I think there’s a big difference.”

“That’s because you don’t understand.”

“Maybe, but I’m trying.”

Elias and I grew increasingly frustrated with each other, and I could sense that he was growing skeptical of my intentions. He told me he had to return to work, so I thanked him for his time. Before I left, he asked, “Are you going to write some report or something?”

“Probably a book,” I said.

“I hope you don’t get it wrong, about the situation here. People who come here and work hard can get ahead, just like I did. People who take short cuts are going to have a bad experience. You can tell everyone that’s what I said.”

I thanked Elias for his thoughts. Despite his arguments that the only issues the migrant workers faced in California’s Central Valley were their own laziness and treachery in abusing the H-2A system, I had documented more than enough cases to persuade me that the migrant workers were by and large honest, hard-working men whose vulnerability and desperation invariably placed them on the wrong end of an exploitative arrangement. Perhaps some might try to game the system, but most had mortgaged so much and undergone such onerous ordeals to make the journey to California and have the opportunity to work on a farm that they were only too grateful to have the job and persisted in the hope of one day being paid the wages they had been promised. In fact, the labor trafficking victims I documented were exploited at both ends of their journey, first by the recruiters who charged exorbitant fees that placed many in levels of debt that they could never discharge, then by the FLCs/crew leaders who imposed excessive wage deductions that meant the workers had almost no money left with which to repay their debts, not to mention the fees that were added for the irregular migrants at the border. Many of the farms in the Central Valley seemed to run on well-oiled systems of servitude and bondage that were akin to almost every other migrant labor trafficking sector I documented around the world, from domestic workers in South Asia, to construction workers in the Middle East, to seafood workers in East Asia. Across the globe, including in the United States, numerous industries operate on the backs of a subclass of vulnerable labor migrants who are recruited, indebted, and coerced to work in subhuman conditions at minimal to no wages under threats of abuse, deportation, or other penalties. After years of research, I could not help but wonder just how much of the global economy operates on this feudal system of migrant enslavement. The precise answer may never be known, but the abuses inherent in the worldwide system of migrant worker trafficking and slavery must be properly assessed and addressed because this system has been woven into much of the global economic order for centuries.

A HISTORY OF LABOR TRAFFICKING

The undeniable truth is that labor trafficking is nothing new to the American agricultural system.8 As far back as the early 1600s, indentured workers were brought to the colonies by the British to work in agricultural fields under systems of peonage and serfdom. As the agricultural economy in the colonies grew and outpaced the available pool of indentured laborers from England, the Atlantic slave trade commenced to meet the labor shortage. The slave trade lasted until the Slave Trade Abolition Act of 1807 was passed in the UK Parliament. Slavery in the United States persisted as an institution until the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1865. The shift from slaves and indentured workers from overseas to migrants from Mexico began in earnest about two decades prior at the end of the Mexican-American war in 1848, at which time tens of thousands of migrant workers from Mexico began arriving in the United States. Most of these migrants moved freely back and forth across the border for seasonal agricultural work; others were ensnared in various forms of forced labor for years at a time. This period of Mexican migration beginning in the mid-1800s coincided with the industrialization and expansion of the U.S. agricultural sector. Indeed, agricultural growth was so brisk that it even exceeded the available supply of Mexican migrant agricultural workers, so the United States resorted to importing Asian farmworkers from the 1860s to about the 1930s. By the end of the nineteenth century, roughly seven out of eight farmworkers in the United States was either from China, Japan, or the Philippines. This led to a xenophobic backlash in the form of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned the employment of Chinese workers. Jim Crow laws beginning in the 1890s then systematized the segregation and oppression of the descendents of African slaves, which pushed many to enter into sharecropping arrangements with white landowners. World War I stymied migration to the United States, causing a new farmworker shortage. In response, the first “guest worker” program focused on Mexican farmworkers was created, and it lasted until 1921. The flow of Mexican migrants went the other way after the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, and 500,000 Mexicans were deported to Mexico due to a glut of farm labor. Eventually, the labor market stabilized. As the agriculture sector recovered, the United States faced another labor shortage, which led to passage of the Emergency Labor Program in 1942, also known as the Bracero (literally “one who works using his arms”) Program, brokered between U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho for an initial five-year term. As a precursor to the H-2A visa program, the Bracero Program allowed for seasonal or temporary labor by Mexican migrant workers in the agriculture and railroad sectors of the United States. Workers under the program were promised equal treatment and wages as those of U.S. citizens. Though the railroad part of the program ended with the conclusion of World War II, the agricultural program continued due to ongoing labor shortages in the sector. Treatment of the braceros was nearly identical to that of many H-2A workers today: extended hours, poor living conditions, underpaid or unpaid wages, physical violence, debt bondage, coercion of labor under threat of deportation, and other abuses. Even the U.S. Department of Labor officer in charge of the program, Lee G. Williams, described it as a system of “legalized slavery.”9 Bracero strikes spread across the country until Congress eventually ended the program in 1964. During its twenty-two-year run, over 5 million braceros came into the United States, making it the largest foreign worker program in U.S. history, larger even than the 3.5 million African slaves brought into the United States during the entire time of the Atlantic slave trade.

The end of the Bracero Program was hastened by the rise of Cesar Chavez’s National Farm Worker Association, founded in 1962, which later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to become the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1966. The UFW has been drawing national attention to the struggles of migrant farmworkers across the United States for decades, and it has helped to inspire the creation of numerous farmworker unions and organizations. Though not as prominent today as it was during the 1970s and 1980s, the UFW continues to organize and advocate for the rights of migrant farmworkers in the United States. In 2016, the UFW lobbied ardently in support of the passage of AB 1066 in California, which for the first time requires that overtime wages be paid to farmworkers in the state when they work more than eight hours per day. The fact that the bill required more than a few minutes of debate is astonishing. Nonetheless, it was passed by the state legislature and was signed into law on September 12, 2016, stipulating a phased-in approach that would culminate in farmworkers in California being paid overtime wages when they work more than eight hours per day, by the year 2022.

Although most Americans do not realize it, their nation’s agricultural system has relied heavily on migrant laborers and slaves from Africa, Asia, and south of the border for the last four centuries. The country’s agricultural sector has functioned to varying degrees on bondage and servitude from the beginning, which is no different from agricultural sectors elsewhere in the world. From feudal times to the present day, the arrangements that characterize agricultural work have been remarkably resistant to change, including in the United States. Laws are passed, awareness is raised, workers protest, and lives are lost—but trafficking for slavery and bondage in America’s agricultural sector remains far more prevalent today than almost anyone cares to admit. Although some laws are now in place in the United States that are meant to protect migrant agricultural workers, based on what I have seen, they are not remotely getting the job done.

Labor laws in the United States have become more protective of migrant workers in the last several decades, but gaps in rights and in enforcement continue to hamper efforts to eliminate severe exploitation in this sector. The most important law that provides protection to all workers in the United States is the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938. This act guarantees minimum wages, overtime pay, and other rights and standards for workers, but the act did not originally cover most farmworkers. Almost three decades after its original passage, in 1966 the FLSA finally included farmworkers, but only on large farms, and only related to certain minimum wage provisions. To this day, small farms are not covered, and overtime wages still do not apply to farmworkers on farms of any size. This lack of wage protection is heavily exploited by crew leaders and FLCs, who extract excess labor under the guise of working off debts, meeting quotas, or paying for rent and food. To make matters worse, the Portal-to-Portal Pay Act of 1947 further limits the scope of compensation to farmworkers by stipulating that travel time to and from the workplace as well as incidental activities performed before and after principal work activities, which can add up to several hours per day, are not subject to compensation. Although the FLSA sets the minimum age for hazardous work at sixteen years, for farm work the age is set at twelve years as long as the work is in the morning or at night. Thankfully, I did not document many cases of child labor on farms in the Central Valley, and certainly not anyone as young as twelve or thirteen years of age. Finally, farmworkers remain excluded from the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which prohibits firing any worker who joins, supports, or organizes a labor union.

The Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act of 1983 is the primary federal legislation relating specifically to migrant farmworkers. The act prescribes certain protections related to payment of wages, record keeping, decent housing, safety standards, antidiscrimination, and written agreements between employers and workers prior to the commencement of work. Crucially, there is no minimum wage provision in the act. Initial violations of the act can be penalized with fines of up to $1,000 and up to one year in prison. Subsequent violations can result in fines of up to $10,000 and up to two years in prison. Neither penalty is an effective deterrent. Inspections and monitoring related to the law are supposed to be conducted by investigators at the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor, but from what I saw in the field their capacity to adequately monitor adherence to the law in the Central Valley of California is severely deficient. Interestingly, the law includes a private right of action for claimants, but enforcement of the law remains anemic. There is not even a centralized database anywhere in the U.S. government reporting the number of cases that have been filed under the law.

The United States Trafficking Victim Protection Act of 2000 provides a basis to punish labor traffickers in agriculture or any other sector. I asked the Department of Justice how many cases had been filed under the act relating to labor trafficking in the agricultural sector, but no centralized data are available. Finally, many of the provisions of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970 also apply to migrant farmworkers, but as I saw time and again, OSHA standards are at best inconsistently adhered to and at worst completely ignored. The consequences of the broad-based lack of enforcement of these and other laws and regulations relating to migrant labor in the U.S. agricultural system is that the invisible migrant workers continue to be coarsely and systematically exploited as they have been for centuries. It is unfathomable that these archaic modes of servitude have persisted in the United States agricultural sector for so long, focused squarely on whatever vulnerable migrant population is trafficked into the country to harvest the food we serve at our dinner tables. To visit farms in certain parts of this country is to go back in time to an era of sharecroppers, serfdom, and slavery. How much longer will this disgraceful time warp be allowed to persist?

THE INDECENT EQUATION

After spending several months conducting research in the Central Valley of California, it was clear to me that I had barely scratched the surface of labor trafficking and slavery in the region. However, the research I conducted was more than sufficient to demonstrate that people around the world eat slave-made food exported from the United States every day. Those same almonds I enjoy in my home are enjoyed in homes in the United Kingdom, Germany, India, China, Japan, Canada, Mexico, and numerous other countries. Although I was not able to gather a sufficient number of cases to express a prevalence rate of labor trafficking in California’s agriculture sector, I documented more than enough cases to know that the problem is real, serious, and significant. Some of the findings from the 303 cases of labor trafficking I documented in California’s agricultural sector include:

• 100 percent males

• $426.30 per month: average wage ($16.40 per day; $1.3110 per hour as compared to average hourly wages of $12.30 for all U.S. agricultural workers)11

• 22.8 years: average age at time first trafficked

• 206 workers from Mexico, 37 from Guatemala, 28 from El Salvador, 32 from other countries in Central and Latin America, and the Caribbean

• 175 workers without documentation; 128 workers on H-2A visas

• 253 cases of debt bondage

• 20 cases of children under the age of eighteen years

The individuals I met lived in highly unpleasant circumstances and suffered numerous health ailments. Exposure to extreme heat, pesticides, and other injurious conditions took an irreparable toll on the workers’ well-being. Most disconcerting of all, the migrant workers shared a near universal sense of fatalism. They felt they had no place to go, no other employment options, and no way to disentangle themselves from their oppressive situation. This mix of exploitation, harm, and resignation left me in an intense quandary I have not yet been able to resolve. Almost everything I eat comes from these farms. As a vegetarian, dairy, nuts, and vegetables are essential to my diet, but it is impossible to know which cheese, almond, strawberry, or tomato is tainted. I contemplated eliminating foods from the specific farms where I documented labor trafficking, but it is impossible to know from which farm the nuts or fruits in my grocery store are sourced. Sometimes the farm is listed, but more often it is not, and with derivative products such as almond milk the producer typically sources from numerous farms. Further, on any given farm spanning thousands of acres, there will invariably be cases of severe labor exploitation mixed with unexploited laborers. Do I reject an entire farm and all its produce because I found a handful of labor trafficking cases on it? One might argue that one case is enough to taint the entire business, but one could also argue that there would always be a small number of infractions on farms even if they do their best to uphold labor standards.

My findings of labor trafficking in California’s agricultural sector have been some of the most challenging for me to reconcile with my desire not to contribute to slavery as I go about my daily life. It has become impossible not to taste suffering with each bite of an almond, oppression in each mouthful of strawberries and degradation with each sip of milk. Every morsel is a reminder of the bitter misery of the slaves I met, transformed into the sweet enjoyment of my nourishment. This indecent equation has persisted for much of human history, and I wonder sometimes if it simply must be so. Perhaps we must to some degree always be sustained by the suffering of others. This possibility gnaws at me because it suggests not only that there must always be a subclass of people in this world whose lives are reduced to bondage and woe but that my entire antislavery career has been pointless. On certain days, this realization shatters me. I endeavor to suppress feelings of helplessness and despondency. I search for signs, for encouragement, for decency, and I cling to the fading hope that there might be a way for me to exist that does not necessitate the degradation of another.

I hope, but I do not know.