No civilized society can thrive upon victims, whose humanity has been permanently mutilated.

—Rabindranath Tagore

A LAND I KNOW WELL

THAILAND IS A country I know all too well. After India and the United States, it is the nation in which I have conducted more research into slavery than any other in the world. Each trip I have taken to Thailand has been a fusion of conflicting and frustrating experiences. On the surface, the country’s beauty mesmerizes me. Its pristine beaches, azure seas, and mist-capped hills are sublime and enthralling. I have been lost for days hiking in its verdant mountains and found solace gazing at the ocean from its powder-sand shores. However, beneath this surface I have also unearthed Thailand’s grotesqueries, the beasts beneath the beauty, the right-hand pane of her Garden of Earthly Delights. There is suffering, inhumanity, and misery in Thailand, and it has consistently worsened across the fifteen-year span of my research trips to the country. Despite all the attention and resources deployed to combat slavery in the broader Mekong subregion, the situation in this steamy corner of the world has persistently degraded. Mass graves of trafficked Rohingya migrants uncovered along the Thai-Burmese border in May 2015 put a macabre exclamation point to just how vile conditions have become.

The sex trafficking industry in Thailand is undeniably ruinous and savage, but conditions in the country’s seafood sector may be even worse. From a mortality standpoint, it is the most severe face of contemporary slavery I have encountered. The industry chews up human beings without mercy. In doing so, it has become the foremost scourge of slavery in global supply chains. Supply chain research has been a key focus for me during the past several years, and I have investigated slavery and child labor used in producing commodities exported to the West, including seafood, handmade carpets, coffee, tea, electronic component minerals, apparel, dimension stones (marble, limestone, granite), gold, precious gems, palm oil, sporting goods, and more. I targeted my research on seafood in South Asia and East Asia, primarily in the shrimp sector. The presence of slavery in global seafood supply chains is a subset of the broader category of offenses called “illegal, unreported, and unregulated” (IUU) fishing. IUU fishing refers to all open sea or aquaculture fishing that takes place outside the authorization, regulation, or legal frameworks of the relevant states or laws of the sea.1 No one knows exactly what portion of global IUU fishing activity can be attributed to slavery; however, estimates for the total value of IUU fishing are between $10 billion and $23.5 billion per year,2 which suggests that billions of dollars’ worth of seafood are caught and processed by slaves annually. Most of this activity takes place in East Asia and China, and more than half of global seafood exports from these regions are bound for the United States, the European Union, and Japan.3 Thailand is the third largest exporter of seafood on the global market, hence abuses in its seafood sector touch the world.

My interest in Thailand’s seafood industry was first piqued by Police Lieutenant Colonel Suchai Chindavanich when he described some of the sector’s atrocities during an interview in 2005 for Sex Trafficking. We spoke at length about human trafficking in the greater Mekong subregion, and toward the end of our conversation he spoke passionately about the brutalities of the Thai seafood industry:

They are mostly Cambodian boys trafficked to the town of Aranya Prathet by bus. From there, a Thai agent takes them to the town of Samut Sakhon, on the coast south of Bangkok. The boys are taken to sea where they are forced to catch the fish twenty hours a day for many months. The ship captains force the boys to take amphetamines so they can work nonstop. Other ships come from the coast and transfer the fish, but the boys are kept on the ship.4

When I asked Colonel Chindanavich what happened to the boys at the end of their time at sea, he said many were shot and thrown overboard. I was astounded. Could these kinds of atrocities truly be taking place in full knowledge of major law enforcement authorities and with seemingly little being done about it? I resolved that day to learn more about Thailand’s seafood industry. As soul-wrenching as my research into sex trafficking in Thailand was, researching the seafood sector took me to my limits. If I had to do it all over again, I am not sure that I would.

SAMUT SAKHON

My journey began in Samut Sakhon. Hot, debilitating, dreadful. It is the largest of the four main fishing provinces in Thailand, the other three being Ranong, Rayong, and Songkhla. Shrimp is king in Samut Sakhon, but seafood companies there also export several species of tuna (albacore, skipeye, bluejack, yellowfin), squid, crab, and lobster. In addition, many of these companies export pet food and animal feed for livestock to the West; both are made with trash fish or fish by-product. Trash fish are the small, inedible fish caught in fishing nets that are discarded by most fishing fleets around the world, and fish by-product includes the discards from fish processing facilities, such as roe, skin, bones, heads, and entrails. What is rejected elsewhere generates substantial profits in Thailand.

I did not have the resources to tackle the entire seafood industry of Thailand, so I focused on the shrimp and trash fish sectors. I could not visit all four of the main fishing provinces, so I focused on the two largest: Samut Sakhon and Songkhla. At the former, I found workers trafficked mostly from Cambodia, and at the latter I found workers trafficked mostly from Myanmar. All the workers, even those being paid a reasonable wage (by Thai standards), were suffering under brutal conditions that ground them to the bone without pity.

Conducting research in Thailand’s fishing provinces was fraught with challenges. It took a great deal of time to build local trust and to ascertain how to gain entry and conduct research on the fishing docks without attracting negative attention. This was particularly difficult during the last few years of my research when the Thai seafood sector came under heavy international scrutiny for slavery abuses uncovered by several excellent journalistic investigations by the Guardian, Reuters, the New York Times, the Associated Press, and others. Environmental conditions also created challenges. The sweltering heat and humidity of Thailand perpetually assailed my productivity. As searing as the weather is during Thailand’s summer months, conditions on the docks at Samut Sakhon were worse. The heat was oppressive, and the stench of fish suffused the air. Each breath at the docks was a labor, and trying to concentrate while dripping with sweat and attempting to navigate a maelstrom of activity to conduct meaningful research was a serious challenge. Throughout the interviews I conducted, mad dogs growled and scavenged for fish scraps, foremen barked orders, scores of workers made an immense racket as they toiled feverishly to unload thousands of blue barrels of iced trash fish from docked trawlers, and another set of workers loaded the barrels of trash fish into filling trucks for transport to the fish meal processing facilities across the province. Faced with conditions highly antagonistic to efficient research, my first trip to the docks at Samut Sakhon was not very productive. The workers appeared to be locked in a system of backbreaking and monotonous work, and there was little room to conduct interviews. Fatigue and fear weighed heavily on every face. The foremen also kept a sharp eye on anything that seemed amiss.

After a good deal of planning and judicious navigation of hostile conditions, I eventually managed a few productive trips to the docks at Samut Sakhon to document the workers. I first identified a relatively calm corner in which to conduct the interviews with the assistance of a translator, although the noise on the docks still made conversations a challenge. My cover story was that I was a researcher from India trying to understand the fishing economy in the East Asian seafood sector. This story did not garner undue suspicion from the foremen and guards, but they did nonetheless require a hefty fee for each interview that was basically a bribe even though it was posed as compensation for the worker’s lost time. The guards did by and large leave me on my own to conduct interviews, but now and again they ambled over to eavesdrop on my conversations. In those moments, I was sure to ask innocuous questions. The informants were always nervous, and many did not wish to complete the interview. Most of the workers I documented at Samut Sakhon were from Cambodia, with a handful from Myanmar and Laos. The Cambodians described their journeys from their homes to Thailand. They all migrated with recruiters who promised work in various sectors, including construction, manufacturing, and seafood. They all crossed into Thailand from four main border cities: Poipet, Battambang, Koh Kong, or Choam. They were all brought straight to the docks, where they were either sent on fishing boats or put to dock work. In either case, they worked around the clock, seven days a week. Many were not allowed to leave the docks and slept there a few hours each night; others went to nearby communal dorms every few nights. They described being paid wages that ranged from $2 to $5 per day, even though Thailand set a minimum wage in 2013 of THB 300 [~$9.25] per day. The working conditions were unsafe, unhygienic, and oppressive. Injury and illness dogged the workers. One Cambodian man showed me his grotesquely blistered fingers and said, “My hands pain so much! But if I do not work, they will bash me.” There was little I could do to help the workers because I did not know at that point whom I could trust in Thailand to intervene, or what the consequences of an incomplete or poorly planned intervention would be. In the end, I gathered enough evidence to determine that every one of the workers I documented in full was being exploited in conditions of slavery.

Some of the men I documented on the docks at Samut Sakhon had previously worked on the trawlers that spend months at sea catching the trash fish. They were reluctant to talk about the conditions on the ships. Their faces were broken and fraught with the lingering menace of torture and torment. Leap told me about a safe house not far from the docks. “I stayed at that place a few weeks after I ran from here,” Leap whispered to me. “I came back because my sister sent me an SMS and said they were being threatened.”

Leap gave me a mobile number for the owners of the safe house. He said many migrants from Cambodia lived there, and most of them had worked in the seafood sector. I rang the number a few times, but there was no answer. I worked through other leads in the Cambodian migrant community, including my translator, and eventually found a possible location for the safe house, which operated in secret. I went to the location and found a nondescript two-story home protected by a cement wall and barbed wire. I rang the buzzer, but no one answered. I noticed a security camera near the top of the entry gate, so I wrote a message on a piece of paper and held it up to the camera: “My name is Siddharth Kara. I am a human rights researcher from the United States. Could I please speak with you?” I added my local phone number to the message. After a few minutes when there was no response, I returned to my hotel.

Two days later, I received a text message from someone who said he lived at the house and asked me to meet him at a nearby bazaar the following day. I arrived at the place and time as instructed, and within a few minutes a small, cheerful fellow introduced himself to me: “I am Anurat.” Anurat said he found my name on the Internet and read about the work I do. That was why he was willing to meet. “How can I help you?” Anurat asked.

I told him about the research I was doing and how a man named Leap told me about his safe house. Anurat remembered Leap and said that many men who stay with him eventually leave because of similar threats. I asked Anurat if I could interview the men at his safe house. He agreed. I documented several former seafood workers at Anurat’s safe house. Their tales left me stunned. Here is what Prak, a former laborer from Cambodia, told me:

The recruiter said we can make good wages in Thailand. He said we will earn THB 10,000 [~$320] each month. More than twenty men from two villages went with the recruiter. He took us in a truck to Samut Sakhon. When we arrived, he said he sold us to the ship captains. I did not understand what this meant. The police at the docks said we had to go on the ships or they would arrest us for entering Thailand without documents.

I worked on the first ship for five months. The guards treated us like animals. They shouted at us and beat us. We had to work all the time. We did unloading the fish, cleaning the ship, making the repairs. If we complained, the guards tortured us. They chained us to the deck to burn in the sun. They threw men overboard to drown. They gave us electric shocks. I saw six men killed on those ships. Some men were so afraid they jumped into the ocean and drowned themselves. My best friend Chan drowned himself. He said, “I will decide how I die, not them.”

After five months, the captain sent me to another ship. I was on that ship for seven months, then I was on a third ship for three months. After this time I came back to land for the first time. I worked on the docks unloading the fish and was paid a wage for the first time. After some time the guards said I would go back on a ship. I told them I did not want to go back, but they said I had no choice. I was very anxious those days, so I decided I must escape. I ran away one night and was living on the streets when I learned of this place. Now I am safe.

I have nightmares about the ships. In my dreams I am trying to work, but I cannot move my arms. The guards shout at me. One of them is going to shoot me, but I wake up before he does. For a moment, I cannot tell if it is a dream or real. Then I remember.

Prak asked if we could stop for a while and have something cold to drink. It was clear to me that he suffered from severe PTSD in addition to chronic pain from several broken ribs that had not healed properly and other health ailments resulting from malnutrition and repeated sunstroke. Even though he was only twenty-seven years old, he looked like a worn down carcass, scarcely able to move his bony frame. After a few years in the Thai seafood sector, only the ghost of a human being remained.

Later that day, Anurat introduced me to his wife, Tina. She explained how they opened their first safe house for migrants from her home area in Cambodia a few years earlier. Most of the migrants had been exploited in the fishing and construction industries. This first safe house was raided by the police. Tina told me the migrants were all sold into “slavery” in seafood. Tina and Anurat opened a second safe house beyond the outskirts of Samut Sakhon, and they kept the location a secret for fear of another police raid. At the time of my visit, they housed nineteen Cambodians, two Burmese, and two Laotians, all of whom said they escaped from conditions akin to what Prak described. In addition to interviewing most of the individuals in their safe house, I also spoke with Anurat and Tina at length. They did not have many good things to say about how migrants were treated in the Thai seafood sector.

“The fish are treated better than these men,” Anurat told me, “We try to help them return home, but we have very little resources. Many of them are in debt to the recruiters, and if they return home, the recruiters will force them to return until they repay these debts. They will be forced to work until they are dead. That is the system.” Tina did not speak to me as much as Anurat, but she uttered one sentence that I will never forget: “People should know where their seafood comes from…. It comes from dead bodies at the bottom of the sea.”

The broader system of exploitation Anurat described to me was further elucidated and reinforced by the migrants at his safe house. They described how traffickers recruit workers from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos and promise them good wages in the fishing sector. They pay bribes to Thai government officials at the border to gain entry and absorb the remainder of the costs of bringing the workers to Thailand. Once they arrive at the docks, they sell the workers to the ship captains for around $600 to $900 each. The ship captains then tell the workers that they each have debts of $1,500 to $2,500, which they must work off on the ships, after which they will receive the wages they were promised. Even if the arithmetic is done correctly, it would take up to nine months to work off the debt at Thailand’s minimum wage; however, the arithmetic is never done correctly (deductions for food, board, etc.), and many workers end up toiling for years with scarcely any income to show for it. Much of this time can be spent at sea. The trafficked workers are sold from one ship to the next and eventually are killed, commit suicide, or return to work at the docks, like Prak. The Thai police appear to be an integral part of the system, at least as it was described to me. I did not see any uniformed police officers on the docks at Samut Sakhon, but Anurat told me they are always in plain clothes and they take bribes to protect the docks and ship captains against inspections. Looking back, I suspect some of the men I thought were guards or foremen were actually off-duty or plain clothes police officers. Each ship captain is supposed to ensure that his ship is registered and licensed with the Thai government under the Thai Vessel Act, B.E. 2481 (1938), but Anurat told me that most ships operate with fake licenses. This means that almost no one is monitoring the working conditions on the ships.

The men in Anurat and Tina’s safe house described the recruitment and transport stages of their journeys in more detail than I was able to gather at the docks. Their stories painted a picture of a highly systematized and efficient trafficking network. Than, a reticent, soft-faced man from Myanmar, described what happened to him:

We left my village on a Monday. There were eighteen of us with two recruiters. They drove us to mountains near the border. From there we had to walk. We walked for eight days through the jungle. I was very tired. The recruiters did not give us food. We ate what we could find in the jungle. Two men fell sick and could not continue, so the recruiters left them. If we did not cooperate, they threatened us with their guns. One man was shot in the chest because he got in a fight with the recruiters. He died. The recruiters made us dig a hole and bury him. One day we came to the end of the forest. There was a truck waiting. They put us inside the trucks and we were lying on top of each other for almost two days when we arrived at Samut Sakhon. There were so many people; it was very confusing. I did not know what was happening. The recruiter said we had to go on two ships that were at the docks. I did not learn until the following day that the ship captain paid the recruiter for us. By that time, we were in the sea and there was nothing I could do.

I pulled out my map and asked Than to show me the area where they walked across the border from Myanmar to Thailand. He pointed to the north, just southwest of Tachilek. Other Burmese men I documented later in Songkhla had been trafficked along the same route. I knew the area well because I had spent several days hiking those same migrant routes a few years earlier. The corridor clearly remained a common route used by traffickers to enter Thailand from Myanmar. It was heavily forested and mountainous and virtually impossible to monitor from a border control standpoint. In addition to this route, a few of the other Burmese workers I interviewed had crossed near the refugee camps near Mae Sot, another common route I documented years earlier that was still being used. The memories of my time near Mae Sot pain me deeply. It was toward the end of a very bleak period of research into sex trafficking in the Mekong subregion, one that left me feeling there was no way to prevent the greedy and barbaric people of the world from devouring the vulnerable and the powerless. Several years later in Samut Sakhon I saw the same predation in a completely different sector. Whether for sex or for seafood, the vulnerable peasants of the Mekong subregion were being trafficked along the same routes into Thailand for the same purpose of soul-crushing exploitation.

I conducted interviews across five days on the docks at Samut Sakhon, three days at Anurat’s safe house, and three days each at two worker dormitories. After my time in Samut Sakhon, I could not see how the forces of decency and justice would ever prevail in a world that thrived so thoroughly on indecency and injustice. I could not comprehend the galling inhumanity required to exploit another human being to the point of annihilation, only to throw him into the sea like last night’s leftovers. The seafood workers I met in Samut Sakhon were being chewed up by a behemoth industry that was fueled by their torment, and to this day far too little is being done to alter this reality. As downcast as I felt in Samut Sakhon, my sense of despair only worsened when I traveled to Songkhla and learned of the plight of the Rohingya.

SONGKHLA AND THE ROHINGYA

Songkhla Province is in the south, on the eastern coast of the narrow strip of Thailand that juts down like a spear toward Malaysia. The top half of this spear is divided vertically with Myanmar, which takes the west-facing land. These two geographic aspects of Songkhla—the proximity to Malaysia and the proximity to a porous border with Myanmar—created a catastrophe for the Rohingya people, a persecuted Muslim minority in Myanmar who fled en masse in search of safety in (predominantly Muslim) Malaysia and Indonesia. Tragically, those few hundred kilometers between the southern tip of Myanmar and the northern border of Malaysia became a feeding ground for traffickers who brutalized the displaced Rohingya in every conceivable manner. Their unconscionable suffering continues to this day.

The main city in Songkhla Province is Hat Yai, which is the primary staging ground for trafficking people from across the Mekong subregion into Malaysia. In Sex Trafficking, I share the story of Lisu, a young hill tribe girl from the north, who was driven through Hat Yai on a fake tour bus with numerous other girls and forced into prostitution at a hotel in Malaysia. The sophistication and formalized nature of the network that trafficked Lisu astounded me, and I learned that the same networks continue to operate along the same routes year after year. This fact alone leads one to the inevitable conclusion that the authorities in Thailand have limited interest in truly combating the human trafficking networks in their country.

The docks at Songkhla proved slightly more favorable for conducting interviews than those at Samut Sakhon. They were smaller and not quite as manic, even though the workers still toiled at a feverish pace. As with Samut Sakhon, there were plenty of stray dogs scavenging at the docks, and the entire environment dripped with the pungent scent of near-rotting fish. However, there were some relatively quieter periods at the Songkhla docks shortly after midnight, when work slowed and the guards tended to be less vigilant. I spent a week conducting interviews between midnight and four in the morning at the docks and was able to document more cases than I did in Samut Sakhon.

Most of the workers I documented in Songkhla were from Myanmar, and they crossed into Thailand from the mountainous border just to the north, near Ranong, or from the refugee camps near Mae Sot. Their stories of recruitment, trafficking, and exploitation were carbon copies of what I heard in Samut Sakhon. A worker named Po told me his story:

The recruiters sold us to the ship captains at the docks. I worked on a trawler for some months, I do not know how many. It was my first job, and it was harder than I imagined. We had to use so much strength to pull the wenches and unload the fish. If we were tired, they tortured us because they knew this pain was worse. One man from my village worked until he died. He collapsed just like that one day. I tried to wake him, but he was no longer in this world. They threw his body into the ocean and shouted at us, “Work! Work!”

Our ship was far in the sea, and I could never see the land. I saw other ships sometimes. I remember one night I could see lights and I thought maybe this is land. I was desperate to get off that ship before I died like my friend, so I thought I can go to the land with a buoy, but I never learned to swim so I was afraid I will drown.

After many months, we came back to land. They let me work at the docks. Oh, did I mention that I did not receive any wage for my work on the trawler? The captain said we would receive a share of the catch, but when we returned he showed me a book and said I had a debt from the expenses while I was on the boat and there was no wage left from the catch. After I worked on a second ship, I received a wage of THB 3,000 [~$94] for three months work. I broke my wrist here so I cannot work on the boats any more. I feel lucky, even though my hand hurts every day. These days I pack ice on the barrels.

I thought nothing could be worse than my life in Myanmar. I was wrong. I want to go back home, but this is not an option.

Po’s tale of blatant and callous exploitation was repeated with appalling similarity by most of the other men I documented in Songkhla. None of them received a written contract for work. They had all been trafficked under the false promise of decent work and good wages in the fishing sector, only to end up as slaves. They all had various injuries—cuts, broken bones, burns—that were not healing properly due to a lack of adequate medical care. Injuries at sea were the most problematic. Several men told me that when a man at sea was injured so severely that he couldn’t work he was simply killed. This threat of execution pressured many workers to toil through their broken bones and other injuries, which only compounded their ailments. Another worker I documented, Thet, told me that his ship captain punished his workers if they got injured. “One man broke his finger in the wench. He was screaming. The captain and his men tied him down and gave him electric shocks from the spare battery. The captain said if he was not careful he could harm others, so this would teach him to be more careful. They shocked him until he vomited.”

In addition to the docks, I was able to document numerous Burmese seafood workers at migrant dormitories. Several of these workers had been trafficked into Thailand using Tor Ror 38/1 papers. Although no longer in use, these special registration papers were once provided to migrants with permission to stay temporarily in Thailand, and they were especially used with workers from Myanmar. All of the workers I met had their papers confiscated once they arrived at Songkhla. A few of them said the police were the ones who confiscated the documents. Others said the ship captains took them. Even though none of the workers had their papers, they all knew they had been in Thailand far longer than the period they were allowed, and the threat of imprisonment, fines, or deportation back to Myanmar with minimal or no income to show for their time in Thailand kept most of them at the docks, working day after day in the hope of securing more reasonable wages at some point. This was the same method of coercion that was used with the H-2A guest workers I documented in the Central Valley of California. Upon arrival, their documents were also taken, they were exploited in conditions of forced labor, and once they had stayed past the time period permitted in their visas, the threat of deportation with little or no income to take with them was a powerful force of coercion that kept them toiling in servitude in the hope of discharging their debts and being paid a more reasonable wage in the future. Stigma also played a strong role with the Burmese men I documented. “If we go back with no money, the community will say that we were lazy,” Thaung told me. “This will bring our family shame. It is not good for us in the community if people feel this way.”

I tried to interview ship captains at Samut Sakhon, but the frenetic nature of the docks and the high degree of surveillance and suspicion made it impossible for me to do so. The docks at Songkhla were more amenable, and I managed to conduct a few interviews with ship captains. Most of the ships were docked for a few days while their cargo was unloaded and weighed and new crew were secured for the next run at sea. Some of the same workers were taken again, but attrition at sea required the captains to secure new workers. True to form, traffickers were ready with a fresh set of slaves.

One animated captain, Boom, with a hoarse voice and tattoos covering his arms, invited me aboard his ship for a meal while I asked him questions about how the ships operate. “We have three types of vessel in the waters,” Boom explained. “The purse-seiners, the trawlers, and the tour boats.” Boom told me that the purse-seiners operate only at night. They use sonar to search for schools of fish, and upon finding them circle them with a net, which is then closed from underneath the fish to capture them. Workers haul the nets on board, unload the fish, and place them on ice in a cargo hold beneath deck. Unlike the purse-seiners, the trawlers operate both day and night. There are two kinds of trawlers, single and double. On the trawlers, the nets are lowered into the water and hauled behind the boat for several hours before being pulled back onboard. The trawlers tend to be larger and go much farther out to sea than the purse-seiners. Most of the workers I documented at Songkhla and Samut Sakhon were exploited on trawlers. Finally, tour boats transport food, supplies, and fuel from land to vessels at sea. They also load the catches from vessels at sea and transport them back to the docks where they can be loaded into trucks and sent to processing facilities. Crews on the purse-seiners tend to be between fifteen and twenty workers, and twin-trawlers can have crews of forty or more.

I asked Boom where the boats did most of the fishing. “Waters in the Gulf [of Thailand] are not good; we go outside Thai waters now, towards Malaysia,” he replied.

I asked Boom how he got into this work. He said it was a family business. He hailed from a fishing village just north of Songkhla, and his father bought their first trawler when he was a boy. “I took command of the ship after my father became old,” Boom explained. “My son will do the same after me.”

I spoke with Boom for most of the evening while picking tentatively at the fried squid he had arranged for us to eat. The squid seemed fresh, but the oil smelled foul like it had been reused too many times. I asked Boom several questions for which I already knew the answer (such as the kinds of boats used in the Thai fishing industry) to keep the conversation light and aligned with my cover story of being a researcher interested in understanding the fishing economy of East Asia. Toward the end of the night I asked Boom about some of the stories I had heard relating to mistreatment of migrant workers. “These stories are not true,” Boom told me. “The workers are lazy. They must learn discipline for the safety of the crew. When we are at sea, everyone must work to their capacity or the ship cannot function. My life depends on theirs, and theirs depends on mine. If we do not have discipline, there will be tragedies for everyone.”

I pressed Boom further. “I have heard that some migrants are forced to work day and night until they would rather drown themselves in the ocean. Is that what you mean by discipline?”

Boom clicked his knuckles, “Why are you asking this?”

“I told you, I am researching the seafood economy of East Asia.”

“What is your purpose?”

“I am writing a report.”

“And will you write that Boom mistreats his crew?”

“I don’t have any evidence that you do.”

“Because I don’t.”

“What about wages?” I asked. “Do you deduct wages as repayment for recruitment fees?”

“The workers are lazy and want to be paid for doing nothing. That is all you need to know.”

“Do you pay recruiters for the workers?”

“How else can I get workers? Do you want me to get them myself?”

“And do you charge these fees to the workers?”

“You are not proper to me. I don’t like these questions.”

At this point, the conversation was getting tense, so I thanked Boom for his hospitality. As I disembarked, he shouted something in Thai toward the docks. Two guards approached me and escorted me outside. They told me not to return. Fortunately, I had already learned almost everything I needed to at the Songkhla docks, so being prevented from returning was not a serious blow to my research. Still, I would have liked to speak with some of the guards, which I did not venture to do in Samut Sakhon. I suspected I could return to the docks at some point in the future when there were likely to be new guards and ship captains who did not know me. As it turned out, I returned to Songkhla a few years later, but this time it was because I was researching the merciless exploitation of the Rohingya people. Their story is one of the most macabre faces of human trafficking I have encountered.

The Rohingya are an impoverished, stateless people who fled from state-sanctioned persecution in Myanmar straight into the hands of slave traders. They number over one million people and live primarily in the northern cities of Rakhine. They were stripped of their citizenship by the Myanmar government in 1982 based on the flimsy determination that they are refugees from Bangladesh, even though they claim to have been living in Rakhine for centuries. Since 1982, the Rohingya have been one of the largest stateless populations in the world. Like the Karen and other similarly persecuted minorities in Myanmar, the Rohingya have been subjected to oppression, violence, and state-sponsored ethnic cleansing campaigns, and hundreds of thousands have fled the country with little local interest or coverage of their plight.5 Violence against the Rohingya escalated in 2012, catalyzing a new wave of distress migration into the forests and seas in search of safety in the predominantly Muslim nations of Malaysia and Indonesia. Both routes have proved to be fraught with peril, slavery, and death.

When I began researching the plight of the Rohingya, I heard stories of a shift in the business model of many Thai ship captains—from fishing to human trafficking. International pressure following journalistic exposés of slavery and other abuses in Thailand’s fishing industry during 2014 and 2015 led to threats of boycotts by Western seafood importers and a pledge by the Thai government to crack down on the problem. A flurry of government scrutiny of fishing sector conditions resulted in the revocation of 11,700 licenses of fishing vessels in October 2015 for offenses relating to labor abuses and other regulatory infractions. The increased scrutiny by the government displeased many ship captains, who were ordered to pay fines, secure new licenses, or cease operations. At the same time, thousands of Rohingya were fleeing Myanmar by sea, and some Thai ship captains saw a business opportunity. On a per-kilogram basis, a ship full of people can fetch roughly three to four times as much money as a ship full of fish. In addition, a ship can be filled with fleeing refugees in a fraction of the time that it takes to fill it with fish. As a result, many ship captains liaised with human traffickers and began ferrying Rohingya from one country to another, where they were often sold into forced labor or forced prostitution. The new business was called “people transportation,” as if it were a ferry service of some kind. However, not everyone who was hauled into the ships made it to land. In the summer of 2016, as many as ten thousand Rohingya remained stranded in floating prisons in the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea because the ships were denied entry by Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. A few hundred Rohingya have been “rescued” and languish in Malaysian and Thai detention centers, but thousands remain incarcerated in these floating prisons, waiting to be ransomed, sold off into slavery, or worse. Survivors in detention centers report being held in cargo holds (like Mustafa and Equiano), with scarcely any room to move, and being tortured, raped, or worse. These maritime trafficking networks continue to expand, with Rohingya victims arriving by ship to Sri Lanka and India in early 2017.

I was unable to document the transport or harboring of Rohingya people at sea. The ship captains, dock workers, and local experts with whom I spoke all repeated the same rumors, but gathering firsthand evidence was impossible. All indications are that the phenomenon will continue due to the worsening economic conditions in the Thai seafood sector, which pressure some ship captains to find other ways to stay in business. The flow of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar has provided these and other exploiters with a prime opportunity to make a great deal of money by trafficking in people rather than catching fish. Efforts by enlightened members of the Myanmar Parliament to pass a bill that would initiate a citizenship verification process for the Rohingya in an attempt to legitimize their presence in the country were soundly defeated in May 2016, and the Rohingya remain highly vulnerable, persecuted, and desperate to flee.

For those Rohingya who fled Myanmar by land, the perils were perhaps even worse than those who fled by sea. On May 1, 2015, thirty-two bodies of Rohingya people were discovered in a mass grave in a remote mountain area of Songkhla Province in Thailand. On May 24, 2015, Malaysian police discovered 139 graves in a series of abandoned camps used by human traffickers on the border with Thailand. Local human rights activists suspect dozens of similar mass graves remain undiscovered in the northern forests of Songkhla, filled with hundreds, if not thousands, of Rohingya corpses. The Rohingya who survived these camps report that they fled from Myanmar with traffickers and were held captive in the forest, either for ransom or until they were sold off to other traffickers, most likely for forced prostitution or forced labor in the Thai fishing sector. Survivors of the forest prisons reported having their teeth pulled out with pliers, women had breasts chopped off and suffered gang rape, and, of course, murder. I was not able to find or document any Rohingya workers at the docks in Songkhla or Samut Sakhon, or in the nearby worker barracks or safe houses; however, I was told by other workers that they had seen many Rohingya at the docks, all of whom were sent on ships to work at sea.

Very little firsthand research has been conducted on the plight of the Rohingya, and no one really knows how many are being slaughtered, held in prisons, or sold as slaves. Even worse, the international response to the crisis has been a failure. No one has any problem calling out the slaughter, torture, and enslavement of the Rohingya, but when it comes time to take the steps necessary to stop the crisis, the international community has been all but inert. In the absence of a more robust response to protect the Rohingya, there is no telling how many will be trafficked, extorted, enslaved, tortured, or killed as a result of their oppression at the hands of the Myanmar government and our collective failure to protect them. They are a stateless, displaced people the world has shunned—a microcosm of the broader functioning of contemporary slavery. If we cannot protect the Rohingya when everyone is staring right at them, there is little hope we can free all of the oppressed, vulnerable, and invisible populations of the world as they toil, suffer, and die in the shadows of the slave economy.

HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

With seemingly endemic levels of servitude in much of the Thai fishing industry, it is crucial to understand how the sector arrived at this point and whether there is any hope for a systemic remediation of conditions. Thailand has more than 2,600 kilometers of coastline, and the fishing sector has always been important to the nation’s economy. Beginning in the 1960s, the country’s largely rural, low-technology fishing culture rapidly modernized. The fleet of Thai fishing vessels was upgraded, and along with a lack of regulation this led to significant overfishing and the depletion of fish stocks in the Gulf of Thailand.6 Catch rates have decreased from roughly 300 kg/hr in the 1960s to a rate around 14 kg/hr in 2015.7 With this sharp reduction in catch rates, it takes significantly more time to catch the same amount of fish as before, and as with any business, time is money (fuel, labor, etc.). The depletion in fish stocks in the waters near Thailand have been particularly severe, but it follows a similar trend globally, with roughly 85 percent of all commercial fish stocks around the world now being fished up to or beyond their biological limits.8 In addition, the rise in fuel costs beginning in the 1990s added pressure on the fishing sector to cut costs. These and other pressures led to sharp cuts in wages for seafood workers and a deterioration of working conditions, which dissuaded many Thai laborers from entering the sector. As a result, Thailand’s seafood sector began to recruit migrant workers to meet labor needs, which resulted in a cabinet decision by the Royal Thai government in 1993 to grant official permission for migrants to work in the country’s fishing sector.9 Meeting labor shortages with migrants was not enough, and several broader global economic and sector-specific forces continued to push the industry to cut costs further to remain viable. First, the wholesale price of frozen shrimp dropped steadily during a fifteen-year period beginning in the early 1990s.10 Next, an outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS)11 in 2012 wreaked havoc on the Thai shrimp sector. Indeed, Thailand has yet to recover to its peak of 380,000 tons of shrimp exports in 2011.12 With exports still down from optimal levels, the industry is losing hundreds of millions of dollars each year. In the face of these pressures, labor costs were the only expense amenable to quick and sustained downward cuts. The Thai fishing sector soon became filled not just with poor migrant workers from across the Mekong subregion but with a significant proportion of migrant workers who are exploited in outright slavery to maintain the industry’s economic viability. Determining the proportion of workers who are exploited as slaves requires further research, but one study found that roughly 17 percent of migrant Cambodian workers in Thailand’s main fishing provinces were being exploited in conditions of forced labor.13 I suspect that the real number of slaves, particularly when robust samples from workers at sea are included, is much higher.

Not to be lost in this mix of environmental and global economic forces affecting Thailand’s seafood sector is the fact that consumers around the globe have expressed a near-insatiable demand for low-price seafood. Global seafood consumption continues to grow, creating an export market that was worth approximately $150 billion in 2014.14 The United States is second only to China in total seafood consumption, and American consumers spent approximately $96 billion on fish products (food service and retail) in 2015.15 To help meet this need, the United States imported around 2.6 million metric tons of edible seafood products in 2015, worth approximately $18.8 billion.16 Shrimp represented $6.8 billion, or 33 percent, of the total. Thailand, in particular, was responsible for $1.39 billion of the seafood imported into the United States in 2015, around $678 million (49 percent) of which was shrimp.17 Globally, Thailand is the third largest exporter of seafood products behind only China and Norway, with total seafood exports in 2015 valued at approximately $7.2 billion.18 In short, billions of dollars are at stake in a highly competitive global seafood market as consumer demand for cheap seafood rises year after year. Price is the primary variable on which retailers compete to attract consumers and capture as much business as possible. This price competition places powerful downward pressure on costs for producers. Conjoined with other global economic and environmental pressures on the Thai seafood industry, severe labor exploitation has become essential to the competitive profile of many Thai seafood exporters. Can anything be done to protect labor in the Thai seafood industry in a way that ensures its economic viability? Answering this question requires a closer look at the Thai seafood supply chain.

THE THAI SEAFOOD SUPPLY CHAIN

The Thai seafood supply chain is part of the complex global seafood supply chain system. These supply chains involve numerous actors, from small-time fishermen to major commercial fishing fleets, with brokers, wholesalers, importers, other middlemen, retailers, and consumers filling out the chain. Seafood products are shipped straight from the fishing fleet to Western markets or are processed through a multitude of stages before reaching the consumer. Seafood bound for the United States may pass through several intermediary countries for additional processing before arriving. It is almost impossible to trace any particular batch of seafood from the point of origin to the point of retail sale, especially given the combination of products from different sources. Persistent issues with mislabeling of products further complicate reliable supply chain tracing. In short, IUU or slave-caught processed seafood can enter global supply chains at any number of points. Very little can be done to prevent this entry without significant expenditures on auditing and monitoring, which may not be economically viable for some producers. Nonetheless, monitoring may be the only way to provide reliable assurances to retailers and consumers that the seafood they are purchasing is untainted.19

The numerous commodity supply chains I have documented reside on a spectrum, from simpler ones such as handmade carpets from India to more complex ones such as seafood from Thailand. Supply chains are simpler to document and trace when they have the following elements: (1) discrete products that can be labeled and that are not easily mixed with products from other suppliers, (2) small numbers of exporters and importers in the industry, (3) more vertically integrated companies that encompass the full supply chain from production to the point of retail sale, and (4) more concentrated production bases, both geographically and in the number of production sites. Although fish are discrete products, they are almost always mixed between ships, processors, exporters, and importers, especially smaller seafood items such as shrimp. Each product in the Thai seafood industry (shrimp, tuna, squid, etc.) has a slightly different supply chain. Labor abuses in each product line take place at the fishing or processing stages, and the abuses almost entirely involve migrant labor populations. This is especially true with the trash fish/harvested shrimp (as opposed to wild-caught shrimp) supply chain.

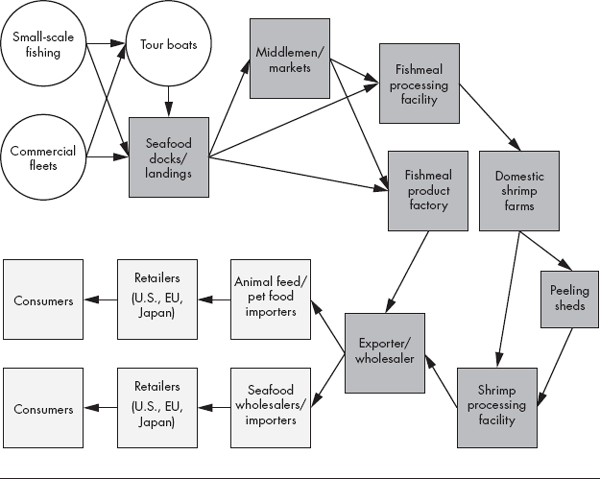

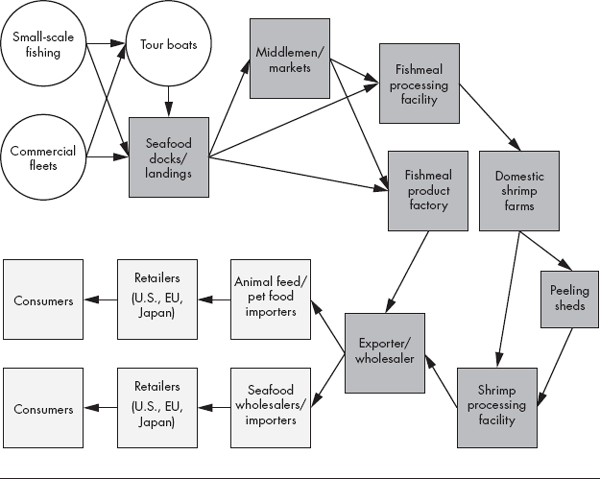

A basic map of the structure of this supply chain provides clear indications of the optimal points of intervention to stem labor abuses (see figure 7.1). Severe labor abuses primarily occur in three points on the trash fish/harvested shrimp supply chain: (1) ships, (2) docks, and (3) processing facilities. The supply chain begins with the ships at sea catching trash fish. These can be either large, commercial fleets or small-scale fishing operators. The ships either deliver the trash fish directly to the docks or tour boats haul their catch to the docks for them. There are roughly 50,000 vessels officially registered with the Thai Department of Fisheries, and tens of thousands more are not registered or operate with fake licenses. These ships source seafood in the Gulf of Thailand, the Andaman Sea, the Straits of Malacca, and in some cases as far out as the South China Sea. Tracing tainted seafood from vessels that use slave labor is challenging because the ships can trade catches while at sea, and tour boats transport catches to the docks from more than one ship. Even if a retailer cuts off one particular exporter definitively linked to slave labor, tainted fish may still enter its supply chain through other exporters.

FIGURE 7.1 The Thai trash fish/harvested shrimp supply chain

The next step in the chain involves unloading the trash fish at one of the main seafood docks around the country, the main four being in Samut Sakhon, Ranong, Rayong, and Songkhla provinces. At the docks, migrant workers load the trash fish onto trucks to be distributed to seafood processors. These trucks may deliver the trash fish to middlemen first, who transport and sell them to fish meal processing facilities or fish meal product factories, or the trash fish may go straight from the docks to either of these two destinations. The docks are the second area in which forced labor occurs. Unlike ships at sea, these are fixed locations that can be more easily monitored. At present, corruption and a lack of enforcement are the primary barriers to ensuring decent labor standards at many of the seafood docks.

After transport from the docks, the supply chain bifurcates into two paths: (1) trash fish that arrive at the fish meal processing facilities enter the domestic shrimp aquaculture market as shrimp feed, or (2) trash fish that arrive at the fish meal product factories are processed for use as pet food or animal feed abroad.

The Domestic Shrimp Aquaculture Chain

Between eighty and one hundred registered fish meal processors in Thailand generate feed for the domestic shrimp aquaculture industry. It is rumored that significant labor abuses, including forced labor and child labor, occur at these processing facilities. My efforts to document conditions at the processing stage were unsuccessful, as I was turned away at gunpoint at the seven facilities I attempted to investigate. Several telephone messages I left for processors also went unanswered. From the processors, the shrimp feed is sold into Thailand’s domestic shrimp farm sector.

Thailand has about 30,000 registered shrimp farms and thousands more unregistered ones, which makes the farming portion of the chain difficult to monitor and regulate. There are three types of shrimp farms in the country: (1) hatcheries for nauplii, or shrimp larvae; (2) nurseries for nauplii to grow into baby shrimp; and (3) growth farms where the baby shrimp mature for a few months to adulthood prior to processing and export. Most of the trash fish–based feed is sent to the growth farms, often through a network of middlemen. Significant labor abuses, including forced labor and child labor, are reported to occur at these growth farms as well. I made efforts to document conditions at ten shrimp growth farms but only succeeded in documenting a handful of cases of forced labor and child labor. I was under almost constant surveillance and could not complete full interviews. Unfortunately, there was no other time or place where I could access the workers.

Once the shrimp mature, they are sent for processing, which includes peeling, beheading, cleaning, and freezing. Some of the peeling takes place in thousands of peeling sheds, primarily located in rural areas in the provinces of Surat Thani and Songkhla. Hundreds of thousands of migrants toil in unregistered and unmonitored mobile peeling sheds where they peel shrimp day and night in forced labor conditions. I documented peeling sheds just like these involving forced labor in Bangladesh,20 and I was able to document six peeling sheds in Surat Thani. There were a total of 107 workers in these sheds, of which I documented 30. All of them were in forced labor and debt bondage. All were foreign migrants; six were children. The conditions were harsh, unhygienic, cramped, and miserable.

Once processed, the shrimp are sent to exporters who ship them and other seafood products from Thailand to the United States, the European Union, and Japan. The seafood is imported by domestic seafood markets or other importers in these regions, who sell to retailers—restaurants and grocery stores—who in turn sell to consumers. It bears repeating that slavery on the ships that catch the trash fish taints the entire supply chain. This is what Tina meant when she told me that the seafood we eat “comes from dead bodies at the bottom of the sea.”

Animal Feed and the Household Pet Food Chain

The second supply chain for trash fish in the Thailand seafood industry involves processing factories that produce household pet food and livestock feed for foreign markets. There are seventy or eighty of these processing factories in Thailand, and many of them are rumored to have forced labor and other abuses in their migrant worker populations. I was not able to verify these rumors, as I was not allowed entry at the eight factories I attempted to investigate, all of which were in Samut Sakhon. All my phone messages also went unanswered, just as they did with the fish meal processors. Following the processing stage, the remainder of the chain is fairly straightforward, involving transport to major exporters, who in most cases are the same as those who export other seafood products, including shrimp, tuna, squid, and crab. The products are imported by the West and used in animal feed (mostly cows and chickens) on livestock farms or sold as household pet food. In the case of animal feed, the entire meat (beef and chicken) supply chain would be tainted by the slave-caught trash fish–based feed that is eaten by the livestock. Household pets would also be eating slave-made pet food by virtue of the same tainted trash fish. The infection of slavery at the bottom of the trash fish supply chain in Thailand permeates several global product lines, from retail seafood to beef and chicken to pet food and beyond, constituting an expansive contamination that touches billions of lives around the world. Add to this the tainted food being produced by trafficked laborers in California’s Central Valley, and the global menu of protein, vegetables, fruit, dairy, and more is vulnerable to infection by highly disconcerting levels of slavery.

Rounding Out the Supply Chain

Both of the trash fish product lines (shrimp and feed) typically are consolidated by major exporters in Thailand prior to being shipped abroad, and I made efforts to speak to executives at the country’s top seafood exporters: Thai Union Frozen Products (TUF), Kingfisher, CP Foods, Pac Food, Rubicon Resources, and Surapol Food. TUF in particular is a multi-billion-dollar, vertically integrated seafood company that controls roughly half of all seafood exports from Thailand. These exporters sell to some of the largest retailers in the West, including Walmart, Safeway, Darden Restaurants, Albertsons, Sysco, and major fish markets in Boston, Los Angeles, and Seattle. I was not granted in-person meetings by any of the companies, although spokespeople at each company told me that they took the issue of labor exploitation in their supply chains very seriously and refused to conduct business with suppliers who were linked to forced labor or other abuses. Each company expressed a no-tolerance policy for human trafficking. When I described some of the cases I had documented among workers in Samut Sakhon and Songkhla, which would surely touch every major exporter in the country, I was informed by each company that they would look into the matter expeditiously.

It is all but impossible to trace a single batch of tainted seafood all the way through the supply chain to the point of retail sale, but a basic supply chain mapping exercise reveals that exploitation must be cleaned up at the ship, dock, and processing stages for all products to ensure that supply chains are fully untainted. The docks and processing facilities are fixed locations that can be monitored, if there is a will to do so. Samut Sakhon should be the priority because more than half of the seafood processors in Thailand are based there. However, even if all the docks and processing facilities are cleansed of forced labor, abuses at sea must still be addressed. These sea-based abuses present a unique challenge to cleaning up the seafood sector. The only reasonable solution would be a system of random inspections at sea; however, many of the abuses take place on unregistered ships with no official reporting obligations. A two-step process would be best: (1) an aggressive and sustained Thai government crackdown on unregistered fishing vessels, including random checks at sea and strict prosecution and punishment of any companies or ship captains discovered to be operating without a license, followed by (2) a system of random monitoring of labor conditions at sea on seafood vessels. One need not monitor every vessel, but if the perception in the industry is that there is a reasonable chance of being boarded and scrutinized, conditions on the ships are bound to improve. Random interviews with workers also must be conducted after they return from stints at sea. Additional support services, information channels, and efforts to promote safe and registered migration of workers will help attenuate the abuses that inevitably occur when populations are invisible and are unable to access assistance and information. These efforts should be undertaken in conjunction with local NGOs, which can help assure a human rights approach to the monitoring process. Project Issara is one such organization in Thailand doing promising work in this area, and it provides a model that can be scaled and replicated. Finally, the Thai government, or perhaps the U.S. Coast Guard, must make every effort to track down every vessel at sea that is imprisoning Rohingya migrants. Why this effort has not yet been made is beyond understanding.

Many retailers in the West that purchase seafood in Thailand have become acutely aware of potential issues with their supply chains and have demanded assurances of decent working conditions at all stages. However, as long as abuses persist at sea, there is no way to ensure that tainted fish do not enter the supply chain of any retailer anywhere in the world due to substantial mixing of catches at the docks and processing facilities. Ridding its seafood sector of slavery rests squarely with the Thai government, but much of the Thai seafood industry as currently constructed may not be able to survive economically without relying on severe labor exploitation. Perhaps portions of the sector can be reconstructed and remain economically viable, paying reasonable wages and providing decent working conditions for migrant workers. Until then, every person, farm animal, or household pet in the United States, the European Union, and other primary markets could be biting into slave-produced seafood, beef, or chicken every single day. I cannot say what the chances are, but that there is a chance at all must not be accepted.

LAWS AND CONVENTIONS: NOT NEARLY ENOUGH

Under increasing international pressure, the government of Thailand has made efforts to address severe labor exploitation in its seafood sector, but these efforts appear to be falling short. In April 2014, the Thai Department of Fisheries launched its “Action Plan and Implementation by the Department of Fisheries in Addressing Labour Issues and Promoting Better Working Conditions in the Thai Fisheries Industry.” The plan called for greater oversight, regulation, and maintaining labor standards across the industry. One promising step involved the revocation of 11,700 licenses of fishing vessels in October 2015 for offenses relating to labor abuses or other regulatory infractions. Unfortunately, local experts tell me that many of the same ship captains whose licenses were revoked were back in business a few months later, either with new licenses or with fake licenses. Rather than being a one-time event, rigorous monitoring of vessels for regulatory or licensing infractions should be an ongoing practice by the Thai Department of Fisheries.

Thailand also has passed numerous laws meant to maintain decent work standards in the fishing sector, including the Thailand Fisheries Act, B.E. 2490 (1947), the Thailand Act Governing the Right to Fish in Thai Waters, B.E. 2482 (1939), the Thailand Vessel Act, B.E. 2481 (1938), as well as an abundance of labor laws. However, most of the laws have significant loopholes, lack enforcement, and are outdated. A more promising development is that Thailand signed the ILO’s Work in Fishing Convention of 2007 (No. 188) and the ILO Recommendation Concerning Work in the Fishing Sector of 2007 (No. 199). The convention and recommendation are designed to establish global labor standards that apply to all workers in the commercial fishing sector, including minimum wages, minimum age to work, maximum daily hours of work, mandated periods of rest, elimination of up-front fees imposed on workers, elevated safety standards, medical care, comprehensive training, and other policies intended to maintain the dignity and safety of work. Thailand is working with the ILO on implementing these standards, although the country has yet to pass sufficiently robust domestic laws to allow it to do so, let alone adequately enforce the relevant laws that already exist.

At the international level, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, is heavily involved in efforts to maintain dignity and decency of work in the seafood industry and overall sustainability of global seafood supplies. The FAO issued a Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishers in 1995, but implementation is inconsistent among most seafood-producing nations, especially those in East Asia. Within Europe, the EU Strategy towards the Eradication of Trafficking in Human Beings (2012–2016) includes language ensuring that supply chains into Europe are not tainted by human trafficking, specifically mentioning the seafood supply chains from East Asia. The UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015 also requires that companies disclose their efforts to ensure that their supply chains are untainted by slavery offenses. Other countries in Europe are contemplating similar legislation, and one can only hope that these laws will be passed and enforced soon.

In the United States, the main law designed to address imports of IUU caught fish is the Lacey Act of 1900. The Lacey Act is intended to stop the import and sale of products that are extracted in violation of the source country’s conservation provisions or international law. There have been a few convictions relating to the seafood sector under the Lacey Act, the largest of which involved a case of rock lobsters from South Africa that were illegally caught and smuggled into the United States between 1987 and 2001. The defendants were sentenced to prison and ordered to pay a fine of $55 million in restitution to the government of South Africa.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 in the United States also provides scope for the prohibition of the import of tainted goods; however, the relevant language relating to this prohibition only became practically effective more than eight decades after the law was passed. Section 307 of the act states, “All goods, wares, articles, and merchandise mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in any foreign country by convict labor or forced labor … shall not be entitled to entry at any of the ports of the U.S., and the importation thereof is prohibited.” The original language of the act included a gaping exception to the import prohibition, namely that the prohibition does not apply to goods for which there is not enough production in the United States to meet domestic demand. This “consumptive demand” exception basically negated the Section 307 prohibition because there is almost never sufficient U.S. production to meet domestic demand for almost any good that ends up being imported, such as rice, seafood, cocoa, steel, rare earth minerals, tea, palm oil, garments, and so on. Across the years, lawmakers attempted unsuccessfully to eliminate this carve out, and, it was finally closed by Congress under Section 910 of the Trade Facilitation and Enforcement Act of 2015 and signed into law by President Obama in February 2016. The act can now be used to ban imports of slavery-tainted seafood products from Thailand, or any other slave-tainted good from any other country, but it remains to be seen just how proactively and rigorously this ban will be enforced.

Numerous other laws, conventions, and treaties offer scope and impetus to eliminate slavery, forced labor, child labor, labor trafficking, and all severe abuses in Thailand’s seafood industry; however, as is often the case when it comes to issues of slavery, words on paper will not get the job done. None of the aforementioned laws, conventions, and treaties—or any other human rights instruments, for that matter—seem to have protected the Rohingya from trafficking, slavery, and slaughter. Action requires will, and when those in power lack will, citizens must force it upon them. Consumers must apply pressure demanding that they be served slavery-free seafood, meat, or chicken and that atrocities such as those befalling the Rohingya are tackled swiftly and effectively. Once a sufficient proportion of consumers demand untainted goods, retailers will have no choice but to respond to keep their business. Market economy forces will then work their way down the supply chain, cleaning up much of the global economy. Until that time, global animal protein supply chains are unacceptably tainted, which means everyone is at risk of eating slave-produced meat each and every day. We are what we eat, and if we eat the products of slavery, we are slaves. Let this thought dictate our response.

UNABLE TO RETURN

During the course of my investigations in the Thai seafood sector, I documented 198 cases of slavery in the fish-catching, dock-work, and peeling-shed portions of Thailand’s seafood industry. These cases involved both current and former workers. Every one of the individuals I documented was a slave in every sense of the word, and I am confident that a significant proportion of the more than 800,000 migrant workers in Thailand’s seafood industry are suffering slavelike exploitation as well. There is a pressing need for more research to document the full scope of these abuses.

Of the 198 cases I was able to document, the key findings include:

• 100 percent males

• 100 percent foreign migrants from Myanmar (101 cases), Cambodia (76 cases), and Laos (21 cases)

• 93 percent involved recruitment by traffickers

• 89 percent did not have a written contract for work

• 80 percent did not have valid documents for residency in Thailand

• 23 percent had proficiency in the Thai language

• 24 cases of children under the age of eighteen

• $68.70 ($2.37 per day; $0.16 per hour): average monthly wage at sea21

• $73.85 ($2.74 per day; $0.20 per hour): average monthly wage at docks and sheds22

• 21.5 years: average age at time first trafficked

• 8.1 months: average total duration of time at sea for ship workers

There are purported to be higher rates of children and females working in the aquaculture and processing stages of the Thai seafood supply chain beyond those in the hard manual labor stages I documented. Although more investigation is needed, conducting research into the Thai seafood sector is fraught with challenges. It is also severely corroding for the researcher and represents soul-wrenching work on the best of days. In 2016, a major foundation offered me full financial and logistical support to build on my previous research, gathering data to express reliable prevalence rates of slavery and child labor across the Thai seafood industry. I did not accept. It is the first time that I declined an offer to build on previous research, and I have been wracked by a sense of failure every since. My research in Thailand pushed me to my breaking point several times, and it has had a lasting impact on my mind, heart, and health. I simply could not find the fortitude to return. I am confident that I will be able plunge into Thailand’s misery again one day, but for the time being, the savagery and ruthlessness I confronted in that country is too much to bear.

REDEMPTION BY THE SEA

Coupled with my experiences at Badagry, my forays into the Thai seafood sector transformed the once alluring and soothing ocean into something dark, painful, and destructive. Human civilization was born next to water, but on balance the seas appeared to me to cause more harm than good to humankind. True, oceans and rivers have provided sustenance from the very beginning and enabled discovery of new lands and trade with new people, but they have also facilitated conflict, subjugation, and slavery. Can the good exist without the evil? Of course not, but the balance is all. In few places have I found greater imbalance than in the global seafood industry. We have been fishermen for millennia, but that pure and ancient ritual has become grotesque in the hands of the global economy. Misery became nourishment; slavery became dinner. I could scarcely bear to look at the ocean after my devastating forays into the Thai seafood sector. The toll was too much. So I fled to a lonely patch of sand on a quiet island, to try to redeem my relationship with the sea.

The patch of sand was on Koh Tao, a remote island in the Gulf of Thailand. I found a small fishing village on the eastern shore and lived in a thatched hut as a guest of a young couple, Rama and Siri. As with most inhabitants of Koh Tao, Rama is a fisherman. He ventured to sea every day at dawn and sold most of his catch to a few of the hostels on the island. The rest he kept for his family. He fished in a wooden boat, the ancient way, with a pole and patience.

I fished with Rama for five days. We sat in silence much of the time, listening to the water, watching the hue of the ocean transform as the sun passed from east to west—azure, cobalt, and gray. My thoughts wandered to the torture chambers further at sea. To wash them away, I plunged into the deep. It was serene, cleansing, meditative. I thought how peaceful it would be to stay.

Rama and I caught mostly grouper and snapper. The experience was not entirely idyllic; the searing sun burnt my skin no matter how much protective lotion I applied. We returned to shore each day by afternoon, and Rama went off to sell his catch. Siri kept the fish she wanted, and I helped her clean and cook them for dinner: lemon, salt, and an open flame. Rama brought back a few beers for us each evening from the nearby market, and we all three ate on the beach at twilight. Darkness falls quickly on the islands. The sky bears shades of sapphire, crimson, steel, and black. Night takes hold without restraint. All is silent, save the placid waves that caress the mind to sleep.

My time on Koh Tao brought me some measure of tranquility, and helped heal a sea that had become scarred with too much pain. It also brought me closer to accepting the undeniable truth of slavery—we consume their suffering. Their suffering sustains us.

May God forgive us.