We read about projects that go over budget and the lament of projects costing so much money in Hollywood that the projects go to Canada, Australia, South Africa, Eastern Europe or other countries. They call these runaway productions. A lot has been written about runaway productions that seek less expensive locales or government tax credits. Its true that in some instances savings can reduce a budget by as much as 35 percent because of a strong U.S. dollar or government incentives. This is especially helpful on television projects where production costs have risen while the fees networks pay production companies have decreased. Producers blame the rising fees on the craft people, unions and guilds for running projects out of Hollywood. That’s not entirely true. What has contributed to running projects out of Hollywood are producers who do not understand the positive side of the words “ego” and “relationship,” and who are worshipers of the written word. They believe the words in the screenplay are sacrosanct and should never be changed, so they try to adjust the production (and its budget) to fit the written words.

Let’s examine that logic. The words of a screenplay are written by a writer sitting alone in a room, dictated by his or her imagination. The writer has little or no knowledge about the inherent problems to production—and why should they? They are writers, and you are a producer. They write; it’s your job to produce. But collaboration is the key to this relationship and you must try to make the shoe fit the foot, with the foot being the budget and the parameters of production and the shoe being the screenplay and the process of production.

What makes an excellent screenplay? Is it the size of the bridges that are blown up or the number of cars that crash in the first ten minutes of the film? Or is it the characters and what they say and feel? We all know the answer to that one. The answer should always be “it’s the characters.” No doubt about it, when a project has solid characters who feel, speak and interact within a good story, the picture has the potential of being an excellent project.

Crafting a screenplay to include characters who are solid, emoting, feeling characters takes creativity, not money. Blowing up the bridge in the story may advance the story but is it necessary for the characters and to the story? Can the story be advanced and achieve the same thing without an onscreen explosion? The characters’ reactions to the dramatic intent of the action or effect should be what makes the project work, not the special effect itself.

So a creative producer who is familiar with reality and is starting to raise the money should first determine, based upon research, how much money can be raised, everything being equal. This is a key phrase! “Everything being equal.” This refers to the project before distributors or financiers demand specific requirements, each of which they feel is critical to protect their end of the risk and which will raise the budget of the project. The requirement of a specific actor, for example. Once the budgetary funds have been determined, then the producer working creatively with the writer adjusts the screenplay to work within the available funds (making the shoe fit the foot). A production breakdown on a production board (discussed in Chapters 3 and 11) will identify some of the creative changes that might need to be made. It may mean changing certain locations, which do not work for the production or are too expensive, adjusting the number of characters in the story or perhaps setting certain limitations as dictated by budget. Limitations are always part of the formula. Creativity flourishes within limitations and restrictions. Mozart had a deadline when he was commissioned to write The Magic Flute; the Pope continually pressured Michelangelo with deadlines for the completion of the Sistine Chapel. Limitations can force you to stretch your creativity in new (and often cost effective) directions.

As previously mentioned The Girl, the Gold Watch and Everything had a screenplay that the studio said would cost over two million to produce. I knew that if I produced the film from scratch and had to find or build all the locations and did the scripted special effects the way that was standard at the time, it would have cost what the studio had projected or possibly even more. This was prohibitive for a movie for television. We were doing a union (IATSE) picture and set construction alone with an IA crew would have taken the entire budget. The final script the studio Budget Department read had already been reworked with the writer with the “shoe fit the foot” theory. I decided to walk the studio soundstages to see what sets were standing and what sets could, with changes to the set dressing or minor alterations to the screenplay, be used for Gold Watch. I found a wonderful hotel suite which would match into the Hotel Del Coronado in San Diego, and an interior being used for a romantic comedy which could also be matched with exteriors into the project. This tenet of producing, of maintaining picture quality and creativity and having the “shoe fit the foot” prevailed through the entire production process.

Hunter’s Blood was faced with a different problem. The executive producer had wanted the project shot in Florida, thinking that the terrain of northern Florida was more suited to Arkansas and Oklahoma where the story was set. (She was also from Florida.) I was faced with finding locations in Southern California that could work for the picture. I knew that what was important to the movie were the people, not the trees and shrubs (although there couldn’t be any palm trees in the film) or how the landscape was dressed. So I needed to find exterior locations that could pass for the woods of Arkansas. I knew the first draft of the screenplay would need changes to coincide with the vision I had of two cultures clashing with one another. I spent weeks looking within a fifty-mile radius of our production office. Finally I found a woods on a “location backlot” in Newhall, California, just behind the Six Flags Magic Mountain Amusement Park. Once I found the woods, I asked the lot manager what else was situated on the lot. He drove me around and I saw areas that—with some rewriting and clever set dressing—could work very successfully for the film project. I also found a practical (that is, working) freight train and about five miles of track. When I showed this to the writer we changed the ending of the picture and added two exciting (but inexpensive) stunts to the project. Once again, the shoe was made to fit the foot!

You have raised the funds for the project. You have restructured the screenplay so that the shoe fits the foot. Now you are faced with producing the project. But before you begin, there are two words that you must distinctly grasp. These words may be the most important concepts that you can gain from this book. The words are: Relationships and Ego.

Lot–The area comprising a production studio; it may include office buildings, sound stages, dressing rooms, etc., and is usually protected by guards at the front gate who regulate entry of non-employees.

The relationships you build along the path of the profession are the relationships that will stay with you for your entire career. It makes no difference if the relationships are with financial institutions or with grips and electricians. All relationships are equally important. Never burn a bridge. Just reconstruct them! You will learn that the entertainment industry is a very small one and your path will cross the paths of many others again and again. It is your integrity that will keep your relationships in place.

The nature of human relationships relies on the fact that a certain amount of what motivates someone is their relationship to someone else. You may hire a handyman who has worked for one of your relatives for many years to work for you on your house. The handyman wants to make sure he does an excellent job because of his ongoing relationship to your relative as it is important to him to maintain the integrity he has in that relationship. But when he comes to do work on your house, you continually tell him how to do his job. Or maybe it’s a warm day and you don’t show him the courtesy of offering him a cold drink when you see that he is perspiring. In other words, you treat him with disrespect for his labor and the good rapport he has with your relative. This demonstrates a lack of integrity on your part and will be your downfall in establishing a relationship with the handyman. That disrespect may work against you in the future; he will not be as receptive to your needs the second time you call, and your relative may not be willing to refer people to you.

You will find that as your producing career builds, you will go back to the same people for assistance. They will learn from you and you from them. Producing is an art form and we must remember that, as with any art form, it is never just a job; you will need relationships you have cultivated and nurtured in order to be successful. Always maintain your relationships with people. Above everything else, it is the one skill that will allow you to bring about your passionate lifelong project and have people rally around you when you are ready to produce it. I have never been to a cast and crew screening of any project where each and every person there did not feel like it was their own project. As the film unfolded, they each saw, in the far recesses of their minds, their creative contribution and they knew they were a part of the whole. This is what creative producing does. It helps people realize their potential and appreciates their contribution to the birth of the project.

The connotation regarding this word is often interpreted as negative, as in “his ego is so out of line that we just can’t deal with him!” But there is a positive side to this word and the creative producer understands how to exercise it when producing a project. Something as simple as a producer spending five minutes in genuine discussion with a crewmember can positively enforce the ego of that crewmember. That crewmember unconsciously thinks “this busy producer spent a bit of time to find out how I am doing, and not on a production level but on a personal level.” Gil Cates, a favorite producer of the Academy Awards® ceremony, has produced that show longer than any other producer since the inception of the awards. The Oscar® telecast requires a producer with extraordinary skill, taste and diplomacy to carry it off. I have known Gil from the days when he was president of The Directors Guild of America (also known as the DGA), an organization to which I belong. He was one of my “bosses” when he became the founding Dean of the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. For eight years, I went to his weekly “Dean’s Meetings” during which I would watch him skillfully motivate a variety of egocentric academics into ferrying the school to new heights of professionalism. He handled those meetings like a creative producer and maneuvered his creative academic team to all see the same vision. I may not have agreed with all of the decisions he made, but his ability to finesse the various egos and allow each person to know they were valued while contributing to the ongoing success of the school showed me what creative producing is about.

Although I was only one person on the academic administrative hierarchy, Gil knew that my strength in supporting his vision for the school was as a producer as well as a teacher. Many times he would stroll into my office, seat himself in a chair and spend a bit of time with me. During those conversations we did not speak about the work at hand, but instead discussed our families and our lives. Although I knew his interest was genuine, I also knew that, as a gifted producer, he totally understood the positive side of the word ego and was reinforcing mine. When he would leave my office, I felt that he cared to take the time to visit and find out about “me,” and so I wanted to provide more support for his creative vision for the school.

The industry operates on a horizontal basis. If someone works as a grip, then they are thought of as a grip. If someone earns their living as a property person then it is almost impossible for them to be considered for anything other than a property master. What would they know about art direction or production design? While the last sentence is written sarcastically, it is often true. The industry does operate on a horizontal basis. In general, producers do not want to take the chance of using someone in a new capacity for the first time. But a producer who clearly understands the positive dynamics of ego, will, when needed, attempt to work against that policy.

In searching out a production designer for the film project Hunter’s Blood, I found a man who had previously been a property master on big budget major feature films. He came highly recommended by production designers and art directors I had previously worked with but who I could not afford for this particular project. They knew he was a talented property master and probably had the ability to be an excellent production designer if given the chance. After meeting with him, my instinct and their recommendations convinced me to give him a try. I knew that by giving him this opportunity his ego would make him go that extra mile to interpret the vision of the project. Because he was a property master on major films, he knew the volatile demands of production, had the relationships with personnel and prop houses important to the project, and could work within a structured budget. Moving him up to a production designer meant giving him more responsibility, providing him with screen credit in the front titles of the film and allowing him to be creative in a different way than he had been in the past. It also gave him an opportunity to move vertically up the industry ladder and possibly change his position on future projects. Because he wanted this opportunity, he agreed to a lower salary than he would have commanded as a property master, or that I would have had to pay to an established production designer. The result was positive for both of us and all because of understanding the positive meaning of the word ego.

Of course this does not always work, and the risk is based upon the judgement of the producer. Many years earlier I did the same thing on the motion picture The Clonus Horror. But in this case, I made an error in judgement and did not check out the candidate with other people before hiring him. On this project, the concept of hiring a property master as an art director appeared to be working quite well, until the art director was to design and build a set situated in a warehouse that we were using as a soundstage. The film had an eighteen-day shooting schedule. During that time a “clone room” needed to be constructed. While we were shooting on location on a Tuesday, the art director was to have been supervising the building of an approved set design that was to shoot the next day. After Tuesday’s production day, the director (Robert Fiveson) and I stopped off at the warehouse to see the set and discuss the next day’s shooting. When we got there what we found was the art director sitting in the middle of an empty warehouse scratching his head. There was no set. The man had panicked. He had no imagination and was unable to carry out the designs we had discussed. He was a fine property master and set decorator when he was given a set of parameters by an art director or direction from the screenplay, but when he was required to create something that didn’t exist, he panicked and failed. It was a judgement error on my part as producer. But as the person ultimately responsible for the creative aspect of the project, I sent the director and “art director” home, and with a couple of carpenters, an ounce of creativity, my wonderful assistant Carolyn Haber and all the gold mylar paper we could find in the city, we built a clone room and the director was able to shoot the next day. So remember ego is an important word to understand, but make sure that you truly understand it.

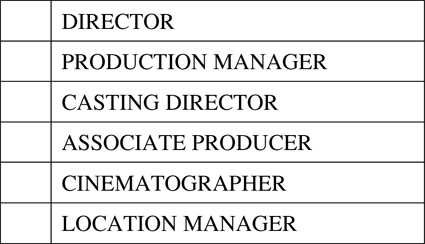

You have your screenplay, you have your budget completed and approved, you have your funding in place and now you are ready to move from the development phase of the project to the production phase. Of the list below who are the first three people you should employ?

CONTINUITY BREAKDOWN PAGE

If you checked any of those production positions, you are absolutely wrong!

The first three positions that you should employ are the producer’s assistant, a production accountant and a production assistant.

The producer’s assistant is your assistant. In other decades they were called secretaries. Today they are referred to as Assistant to the Producer. This is the person who you ask to contact the Screen Actors Guild to get the signatory documents, or to contact a casting director to begin discussions with you. It is this person who is your right hand in getting things together and providing the follow through. It should be someone with whom you can confide and trust. It should be someone you know will get things done in a timely fashion and who will know how you think in terms of creative producing.

The production accountant is the person who must immediately set up the accounting systems on the project. This is not the corporate accountant who assisted in the setting up of the project, but someone who knows how to read a production budget, understands in detail all the guild and union agreements, knows all the basic principles of accounting, and knows how to produce a daily cost-to-complete statement. It must be someone who is proficient in the use of computerized accounting programs and someone who is able to give you answers to budgetary questions at the drop of a hat. It must be someone who understands and recognizes the volatility of production, knows how to help you protect your financial downside of the project, and has the respect of the bonding company or financial community. It must also be someone with the temperament to deal with long hours, short tempers, large egos, quick turn around, angry crew personnel and (of course) stress. This person is your right hand in relationship to the fiscal structure of the project and is critically important to your success as a creative producer.

While every project requires a number of production assistants, each doing different functions working in different production departments, this specific production assistant is considered the producer’s production assistant and will work on getting “tradeoffs” for the film project. A tradeoff is also referred to as a product placement. It takes a great deal of time to put tradeoff agreements in place on a project, which is why the process needs to be started early in the production phase. The production assistant must be a person who has the gift of gab and knows how to sell themselves first and the project second; like any good salesman. The production assistant must be very good on the telephone as well as in person as he or she is representing the quality and integrity of you and the project.

The tradeoff1 agreement is a major assist in helping an independent producer remain within a prescribed budget and providing creative quality onscreen. It allows the producer to save monies in various areas of production, such as locations, properties, wardrobe, set decoration and transportation, etc., by finding mechanisms and methods for displaying product logos or use of a specific product onscreen. The production budget should be prepared as if no tradeoff agreements are in place, so monies that are saved from any agreements eventually made can be put elsewhere to be seen on the screen. Tradeoff agreements for limited budget productions can enhance the details of picture quality and give a small picture a more expensive look. But tradeoff agreements take time to acquire. Many producers do not wish to use product placement as they believe it affects the integrity of the artist and the film can appear to be one long commercial. However, if a producer is careful, creative and selective as to how the product is used and identified onscreen, this perception can be avoided.

The Clonus Horror, produced for $250,000, had tradeoff agreements with Bell Helmets, Adidas, Schwinn, Dr. Pepper and Old Milwaukee Beer, all of which were seen onscreen. In one instance the characters, as a story point, talked about one of the placed products. In another, Robert (the director) wanted all the clones in the picture to look the same and ride the same bicycles. So in the opening of the movie ten clones ride matching Schwinn bicycles, wearing matching Adidas wardrobe and matching Bell Helmets. If the production had to purchase the bicycles, wardrobe and helmets, we would have spent close to $3000 to achieve the look. Through tradeoff agreements we were able to provide the look and acquire more wardrobe for other clones for later scenes.

There are companies whose function it is to place product onscreen in theatrical motion pictures. Product placement companies, sometimes called “promo houses” are listed in the telephone book and in various industry production information manuals. Located primarily in Los Angeles and New York, they get hundreds of calls a day and must be selective as to which projects they recommend for their clients. Companies not represented in this fashion can be contacted directly and eventually your production assistant will find the right person to speak to and make the pitch.

That pitch must contain the right information to successfully involve product placement. Product representatives must know the name of the film project and the names of the people producing and directing. They must also be told how the product will be used and which character will be using the product. They will want to read the script to make sure it enhances the image of their client. The product representative will ask other specific questions before agreeing to place their product and your production assistant should be ready with answers. “Who is in the picture?” They need to ascertain the quality of the project in relationship to the creative community. “What company is releasing the picture?” They need to gauge the distribution merit of the project. “When will it be released?” They need to know when they get the exposure. “What type of exposure are you offering?” They need to know how much exposure they are getting. The script will be a key factor in their decision. Language can be an issue. Nudity can be an issue. Violence can be an issue. Budget can be an issue. Now you can see why tradeoff agreements take time.

They are not easy to arrange, but once you have acquired one tradeoff, others may fall into place more easily. One product company, knowing that another product company is endorsing the film by allowing use of its products may agree to become involved (ego). Also, once you have acquired one tradeoff agreement you have established a relationship with someone who already said yes to you once. If it is a company that represents various clients, massage this new relationship and ask what other clients might be willing to appear in the film. Your new friend has already okayed all the tough stuff by approving your project so maybe he or she has other clients whose products may work for your film even though you may not have identified them yet.

Hunter’s Blood acquired a tradeoff for a Ford Bronco that was used extensively in the film. A product placement company that was headed up by a friend I had known for many years represented Ford Motor Company at the time. After concluding the deal, he then asked me if any characters in the film smoked. The picture is a story of a group of hunters who go camping in the back woods and therefore it could provide an opportunity for someone to smoke onscreen. Before answering him I asked him why he was asking that question. He informed me that he represented a tobacco company and it was getting very difficult in today’s environment to place tobacco products in movies. I asked him what he was offering. He told me that he could not provide money for the product to be seen, but that the company would pay for seven dozen three color embroidered cast and crew jackets for the picture. I agreed. And what you see in the movie is one of the characters smoking (which he was going to do anyway), and a 3-second medium shot of a campfire and an empty crumpled pack of cigarettes. In return I received approximately $10,000 worth of cast and crew morale building jackets during a difficult shoot.

The production assistant working on tradeoffs will eventually move to other production tasks on the project once you hire the heads of certain creative departments. Each department head should have their own relationships in place to do further tradeoffs since they each have creative egos which will motivate them. However, in those cases—as in the ones that your production assistant has developed—you must be willing to agree to those tradeoffs. Remember that tradeoffs are important. The producer should always maintain the creative integrity of the project, but should also be open to inspiration, as you never know what will turn up. The skill to negotiate is a key aspect in acquiring tradeoffs.

The producer must possess skills in negotiating. Every aspect of producing involves negotiations in one form or another. It can be as simple as negotiating for a casting director, or as complex as working through distribution deals or talent contracts. The words “relationship” and “ego” also play into the understanding and skills needed to negotiate, and as the producer continues to produce this will become more and more apparent. There are, however, twelve major points to remember when negotiating.

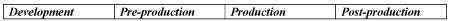

The process of production has a path that is broken into four stages. The development stage is the phase in which the producer is developing the major elements of the project in an effort to raise the money to make the project. Usually the development phase is totally at the expense of the producer and any costs that might be incurred during that time are difficult to recoup from the final project. Development can include preparing the production board, the budget and putting the elements together to release the funds to move the project into the next stage.

Figure 1—The Stages of Production

The second stage along the path is pre-production. Pre-production is the period that commences as soon as the financing has been secured. The producer hires the staff and formally begins the task of planning out the details of the project. The pre-production phase of the project is a fixed phase and does not involve the panic or volatility that exists in the production stage.

The third phase on the path is production, the most volatile stage in the process. It is the phase in which most problems can occur. Murphy, of Murphy’s Law, was an optimist when it comes to the production stage of the film process. Because of this volatility there is no substitution for solid groundwork in pre-production. What the producer fails to do in development will affect pre-production, what the project fails to do in pre-production affects production and what the project fails to do in production affects post-production—all of which will affect the end result.

Post-production is the last stage on the path of the process of production and is the most fixed phase. More than 80 percent of what happens in post-production can be fiscally determined in pre-production. But in order to do so, the producer must have a clear understanding of the entire process or road the project will take to achieve its end result: the finished project or composite answer print. The composite answer print refers to the best possible photographic image (and sound) of the project produced on film as it comes from the original picture negative.

What the producer fails to do in development will affect pre-production, what the project fails to do in pre-production affects production, and what the project fails to do in production affects post-production—all of which will affect the end result.

This simple statement is a key element in creative producing. The producer ought to clearly know the path the project will take to achieve the end result, the better to see and plan for any of the problems that might occur along the way. To do that the producer should scrutinize that path backwards from the projects completion (answer print) and plan out each phase of the process. If the producer analyzes the path forward, from development through post-production, without seeing the end result first (the answer print), the unknown factor of what lies along the path affects the probability of the project running out of funds before it is completed. In other words, think of planning the project from Z to A, rather than from A to Z. When you do this, you will foresee some of the difficulties in producing and plan for them during the appropriate stages of the process. By looking down the road backwards from its completion to pre-production and by planning carefully for each phase, you will be minimizing any potential troubles and assuring that you will have enough resources for the projects’ completion. This way, each phase from pre-production to production to post-production will be much more efficient and productive. In order to try to catch problems before they arise, the producer must start at the very beginning: with the script.

1 Tradeoff agreements are not permitted in commercial television, but are permitted in the cable television and feature film markets.