There is no mystery to breaking down a screenplay. Production managers, assistant directors and producers do it all the time. It is simply a method of reading a screenplay and reducing it to the elements affecting the choreography of production. The breakdown directly affects the pre-production and production phases and indirectly involves the post-production phase of the process. Assistant directors and production managers both break down the project and prepare production boards with an eye to their own responsibilities. Each department head on the project will also do their own breakdown and correlate that to the production manager’s board. As the producer, your requirements are different than the assistant director’s or production manager’s because you need to have your board show you creative issues as they will relate to schedule and budget. Also, the departmental breakdowns only consider the production stage since their involvement ends when production ends. Their breakdowns and boards do not ordinarily consider the post-production stage of the process or the way it impacts the production and the post-production budget. The producer must consider the entire process. This chapter will provide you with the appropriate information for the producer’s breakdown and ultimately the production board, so you can make intelligent and creative decisions.

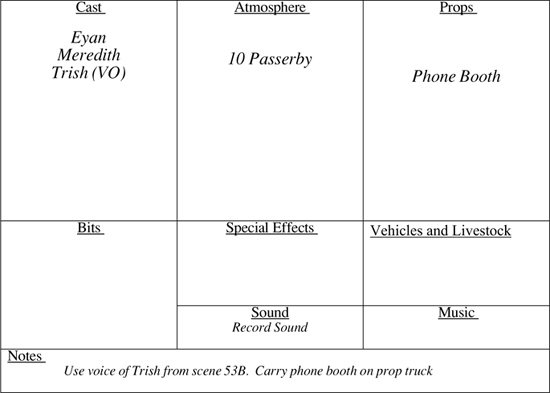

The first step in breaking down a script is to prepare a continuity breakdown page for each scene in the project. These are pages that indicate the logistical elements of a scene as they relate to time and people. As the scene changes (since it may be rewritten), the elements on the continuity breakdown page may also change. These pages become the overall “bible” for the written elements in each scene, since they can pertain to setup and shooting duration during production. They are kept together in a notebook and referred to by either the producer (or sometimes the director), the production manager or the production coordinator. Specific elements from the continuity breakdown pages are translated to production strips, which are then placed on a production board. The production board is used as a mobile tool to assist in the time and labor management of production on a day-to-day basis.

A script must have numbered scenes in order to be broken down. The numbering of scenes is an organizational technique that references story moments for everyone involved in production. It also is a structural guide for post-production editing, and makes for a smooth transition to the post-production stage. Only scenes or slug lines are numbered. To repeat: Only scenes or slug lines are numbered! A slug line shows whether the scene is an interior (INT) or exterior (EXT) scene, its setting, and whether the scene takes place during the day or night. For example:

Sometimes a screenwriter will number the script and in so doing number the shots they may have written into the script. With the exception of the occasional POV shot which sometimes must be written in, screenwriters should avoid writing specific shots into a script. The director interprets a story the way he or she creatively wishes after conferring with both the producer and the writer. Shots may be discussed at that time, but a writer must allow the director the creative freedom to interpret the screenplay and tell the story.

Sometimes writers do not write scenes out completely. They may simply indicate the action. The producer must go through the screenplay and make the appropriate changes to clearly define the breakdown of the story. For example:

By examining this scene carefully, we are able to see there are four different locations: 1) the main room off the front door, 2) the hallway, 3) the bedroom where the burglar waits, 4) the bathroom in which there is a shower. In the middle of this scene, the picture cuts to the bedroom to see the burglar waiting, or the burglar may be just inside the bedroom door and lean his head out into the hallway as Eyan passes. How this moment is to be shot depends on the final choice of location, the ability to have both actors available on the same day, the director’s concept and the time it may take to do the sequence. Because there are multiple variables, upon first breakdown of the scene, the producer should rewrite it to read:

Once the location has been secured and if the configuration of the apartment is one that does not have a hallway leading to a bathroom, the above breakdown is the only way one can see the details of each moment and adjust for them. If the location is going to be a set that is constructed accordingly, then the scene may remain as previously written. This will depend on the producing philosophy of the project and the ability of the producer to have the shoe fit the foot. However, please notice that the scene numbers are different. This is because there may be separate camera positions in each of the locations as the dramatic intent of the story shifts from each location. If it is to be a continuous action sequence then a single strip on the board will reflect scenes 21, 22 and 24 to be shot at one time, with scene 23 being a separate scene in the bedroom.

Sometimes the writer may write a scene and indicate it as a montage.

Here again, since “various stores” indicates more than one but as yet we do not know how many, the scene may have one breakdown page indicating the montage. But a notation should be included that once the stores have been secured, a breakdown page for each store will have to be created. Production will demand new camera position setups in each location and will therefore require separate breakdown pages. However, the scene number for each page is still 35 and it may include a letter after the number, such as 35A, 35B, 35C, etc. Although the sequence is shot in several locations, they are all part of Scene 35 because the dramatic intent of the story calls for Eyan to shop with Trish making the emotional attitude constant. The dramatic intent of the story for that montage has not shifted.

At times, the writer may write a telephone conversation and indicate that it is intercut.

Upon examining this scene we see that the writer wrote it as a two-location, three-character scene. Because there are two locations for the scene—the downtown phone booth and Trish’s house—each location will have the same number: 53. But one will be 53A and the other 53B. They will be shot at different times in the production schedule and in all probability the actor playing Eyan will not be present when the actor playing Trish is doing her dialogue and vice versa. The writer gives an indication to the editor and producer to intercut the scene as they wish which is why the word INTERCUT is written in the margin.

In another example, the writer may have written a scene that calls for the characters to watch something on television. If the sequence on television has to be shot as part of the story, then the sequence on television will have a scene number that will indicate that it works as part of the scene. If the director wants to see the actors watching the sequence then the production will have to schedule the television sequence before the scene in which the characters are watching the television.

Another example may be a screenplay that indicates a POV. Although writers should be discouraged from writing specific shots or angles in their screenplays, they often include a POV as a characters point of view. For example:

The POV shot is really another scene and the sequence should be rewritten as:

From time to time a writer may write a sequence that takes place in a vehicle.

Although the scene is set in a car, the scene location is not the car but instead is the street or highway. The production elements will dictate how the director interprets the sequence. The director can show the car traveling along the highway while the audience hears the dialogue over the exterior shot, or the director can shoot the actors in the car, which will have to be towed by another vehicle.

These examples indicate your need to read the script carefully and attempt to visualize the choreography of production, all while minimizing the dialogue as it has little relevance to the choreography of production.

Once the project is appropriately numbered you are ready to break down the screenplay to its choreographic elements and complete a continuity breakdown page for each scene. The breakdown elements will have a direct correlation to the amount of time and the number of dollars it may take to visualize the scene.

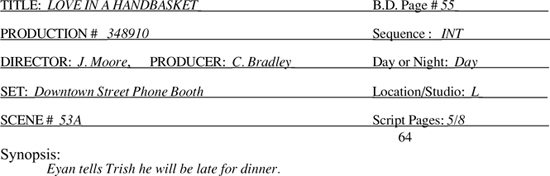

TITLE: The name of the project.

PROD NO.: (Production Number): Sometimes, for accounting purposes, production companies may want to assign a production number to a project. This is especially applicable in television when there are multiple episodes in various stages of the production process.

DIRECTOR: The name of the director (and/or producer).

SET: Description of the setting as indicated within the slug line of a scene. In the first example above EYAN’S APARTMENT is the setting in the slug line of scene 21.

SCENE #: Denotes the scene number, which is opposite the slug line of the script.

B.D. (Breakdown) PAGE #: The consecutive numbering of the breakdown pages. Scene numbers and the breakdown page numbers may not always be the same. Scene numbering may vary depending on the script but the breakdown pages will be consecutive.

SEQUENCE: The INTERIOR (INT) or EXTERIOR (EXT) indication of the scene found in the slug line. Because interior and exterior production choreography have different lighting and set up requirements this can translate to increased production time.

DAY OR NIGHT: The DAY or NIGHT indication of the scene is found in the slug line. This does not indicate the time of day the scene is to be shot, but refers to whether the dramatic action in the story takes place during the day or night. Production choreography shifts dramatically between scenes that are INTERIOR DAY, EXTERIOR DAY, INTERIOR NIGHT or EXTERIOR NIGHT.

LOCATION OR STUDIO: An indication as to if the scene is shot on a location (either distant or local), or at a studio or studio backlot. There are significant differences in organizational techniques between location and studio production.

SCRIPT PAGES: Script pages are broken down into 8ths. Eight/8ths equal one page. This is the yardstick that is used when discussing the length of specific scenes. It permits the director to discuss specific logistics of a scene in relationship to the time it takes to complete a scene. And the scene is talked about in terms of number of pages it takes to present the scene. When indicating the page count do not reduce the 8ths to a common denominator (such as 4/8ths becoming 1/2); keep the count in 8ths. However, if a scene is more than one page do not count the page as 8/8ths, count it as one page. Only count portions of pages in 8ths. So a page and a half scene has a page count of 1 4/8ths, not 12/8ths. One bit of warning however. Because a scene may be 1/8th of a page it does not mean that it will take a brief period of production time to shoot. That 1/8th page might read: “The Indians attack the village” and may require two or three days of production depending on the creative and dramatic vision of the producer and director. NOTE: Write the page number of the script where a scene begins underneath the Script Pages space. This becomes a quick reference if you need to refer to the script.

SYNOPSIS: Write a short one or two phrase description of what happens in the scene:

i.e. “Eyan comes into the apartment,” or “Eyan takes a shower singing Happy Birthday,” or “Eyan and Trish buy clothes on Rodeo Drive.”

CAST: This refers to any member of the cast of characters who says a line or words in the scene. It is listed separately from those members of the cast without speaking parts because actors who deliver lines are usually paid more money than those who don’t. These characters will be the characters who move the action and the story forward. It is important to read the screenplay carefully because a cast member may speak in one scene but not speak in another. Provided they speak somewhere in the script, they are considered a speaking member of the cast. In some instances a major character endemic to the story may not speak at all. In those cases, the character is listed under Cast.

BITS: This is shorthand for “silent bit” and refers to any onscreen talent that does not speak in a scene but does interact with principle actors. Often they are indicated in the description of a scene by a generic name such as waiter, doorman, waitress, bellboy etc. “The waiter brings Eyan and Trish’s meal to the table.” All silent bits in a scene are listed on a breakdown page since they usually receive a higher wage than talent who appear as atmosphere, but a lower wage than actors with speaking parts. The term “bit” is also used to denote a cast member who has one or two lines and works as a day player. They are often referred to as “bit players” since their role is very small in the project. Because they speak they are included in the breakdown page under “cast.”

ATMOSPHERE: Cast members who “people the scene” creating the background are defined as atmosphere. They are sometimes called the “wallpaper” of a scene since the right atmosphere will create an aesthetic texture that translates to the scene. This may be written in the screenplay in the following manner: “Eyan and Trish walk through the crowd of people on their way to the airport gate.” As the producer you will determine the numbers and genders of people who make up the crowd when you break the scene down as you will be thinking about the budget as you do your breakdown. If a specific atmosphere character is required, than the character is listed separately under this category. For example, if the description above read “Eyan and Trish walk through a crowd of people on their way to the airport gate. They pass a tour group of Asian senior citizens.” The Asian senior citizens would be listed as atmosphere but separately from the other atmosphere in the scene and you should determine the number of seniors in the group.

SPECIAL EFFECTS: Indicates any mechanical or makeup effects that might be required for the scene. Mechanical and makeup effects require specialists who will need time to set up for whatever effect is required. If the work is done by an effects company, you will have to know which specific scenes they will be required for. Further, you will need to determine the coordination needed so the effect can be carefully executed on a precise cue as needed creatively by the director. Since the breakdown process is a process that permits the producer to manage time in relationship to creativity, it is important to have special effects for each scene listed.

A mechanical effect is any visual effect that is created mechanically during the production process. Today’s technology permits the producer to digitally create effects. Digital effects are handled in post-production, although images needed for the effect may need to be created during production either by first unit photography or second unit photography. In such cases the project will employ a visual effects supervisor whose job it is to coordinate the elements. Mechanical effects can be anything from mist rising over a river, to blowing up a bridge, to Gone With the Wind’s burning of Atlanta.

A makeup effect is required by the story and performed on an actor to create a specific effect. Jim Carrey went through many hours of makeup effects to become the Grinch before starting work each day for Universal’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas. If a character dies onscreen and the script calls for a visible gaping wound, the scene will require a makeup effects supervisor. These effects will take time and you will need to know for which specific scenes they will be needed, so they are included on the breakdown page.

When determining what production effects are needed, the producer must read the script carefully and logically think the elements through. Examples of a special effect may be as vague as: “Eyan and Trish make love in a steamy shower.” The actors would not really be acting in a shower that was so hot that it created steam. But since the writer and director call for the steam as an effect to translate the creative internal characterizations of the moment, the steam would have to be created by an effects person.

SOUND: This box is used to indicate whether a scene is to be shot with sound or silently. Most scenes have dialogue and therefore production sound needs to be recorded. But directors and producers like to record sound for all scenes whenever possible whether there is dialogue or not. The ability to record sound during a scene requires placement of a microphone, which can affect the time it takes to do a shot. However, in many scenes it is not necessary to record sound as the sound can be added in post-production. For those scenes this space on the breakdown page is marked with the letters M.O.S. According to film lore, the acronym M.O.S. has its origin in the early days of sound when well-known German directors were asked to come to Hollywood. As I heard it, the great German director Ernest Lubitsch was directing a scene that had no dialogue and just before the camera rolled Lubitsch was asked by the soundman if he wanted the sound recorded since there was no dialogue. Mr. Lubitsch responded very dramatically “No, ve vill do this scene mit out sound.” And to this day, the expression “mit out sound” is translated to M.O.S. If a scene is written in the script as “The van pulls up to the curb and stops,” it is not necessary to record the sound since the sound effects would be added to the scene later and you can make the decision to do the scene M.O.S.

MUSIC: This space indicates if music is needed to shoot a specific scene. If it is, it will require the ability to have pre-recorded music played back or the recording of live music in the scene. This will require more production elements than are customarily used in production and will add time to the production of the specific scene.

PROPS: Although the property master will do a breakdown, the producer must indicate any items that are handled by actors or help to create the mood that are written into the description of the scene.

“The camera moves past a lantern, an ax stuck in a tree stump, and a rusty wheel barrow before it settles on Eyan and Trish who are sitting having lunch.” The lantern, ax, and wheelbarrow would be written on the breakdown page under props, as would be the lunch. Writers include props and descriptive elements to point up the creative intent of the story. By indicating what props are called for in the script the producer is able to see if there will be any major prop issues that may be problematic or need to be solved by tradeoff relationships.

VEHICLES AND LIVESTOCK: This space lists any vehicles or livestock that might be required for the scene. This does not refer to vehicles or livestock that may be needed to transport production elements but refers only to those that appear onscreen. Including them in the breakdown again provides the producer with the opportunity to see if there are any major vehicle or livestock problems that may be problematic or solved by tradeoff relationships. It may also be necessary to schedule a vehicle or animal on a production board as one would an actor. This is the case when the vehicle or animal is specific to a character and you need to know on which day it appears in the schedule. They will require personnel to monitor or transport it for the sequences.

NOTES: At the bottom of the breakdown page is a space for the producer to indicate any ideas or additional production elements for the scene. “Trish and Eyan are walking on the beach at sunset.” A special note for this scene might refer to shooting it at magic hour or using a steadicam.

Magic Hour–The time of day on exterior locations just before the sun rises or sets. This usually lasts about 20 minutes.

Computer programs like Movie Magic and Turbo Budget A/D are used commonly throughout the industry. These programs permit the input of the data that appears on every breakdown page. They also allow for other information eventually used by the production manager or first assistant director, such as the whereabouts of each set or location. As these programs manipulate data, they easily permit the production manager to quickly generate the schedules and lists used during production. They are also able to create a breakdown format from a computer-generated screenplay and the breakdown information will be as accurate as the accuracy of the data in the screenplay. Therefore the producer should check the breakdown for accuracy.1 These programs will also generate strips which are inserted into colored sleeves for a production board. While these are wonderful time-saving tools, when you prepare the strips by hand you begin to see the choreographic elements of production and there is something quite visceral with this process that brings you closer to the vision of the project. Once the screenplay is accurately broken down the next step is preparing the production board.

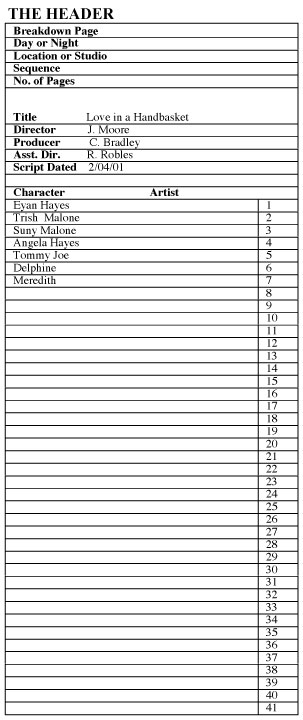

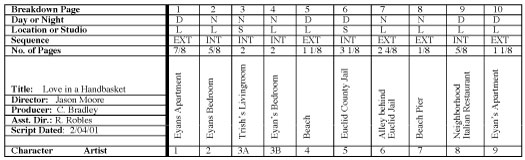

A production board has two, four, six or eight panels. A six or eight panel board is the standard board for a feature length project. Each production board consists of at least one header and various color strips. The header is placed at the front of the production board and captions out the specifics of what may be indicated on each strip. Strips are narrow color cardboard bands on which specific information is transferred from the breakdown sheets that correspond to the captions on the header. At least four different colored strips are needed for the board representing interior day, exterior day, interior night and exterior night. By seeing these colors at a glance you immediately know that each have their own production requirements. If the project calls for scenes that would have unusual production characteristics (such as scenes that take place in moving vehicles), it is not unusual for these to be indicated with another color strip as well.

The first task on the header is filling in the title of the project, and the name of the director (if known) and the producer and the date of the most current script used in breaking down the board. All work is done in pencil, so it can be erased. In the blank area between the number of pages and the title, you should provide a brief legend as to a color explanation of the strips.

Figure 2

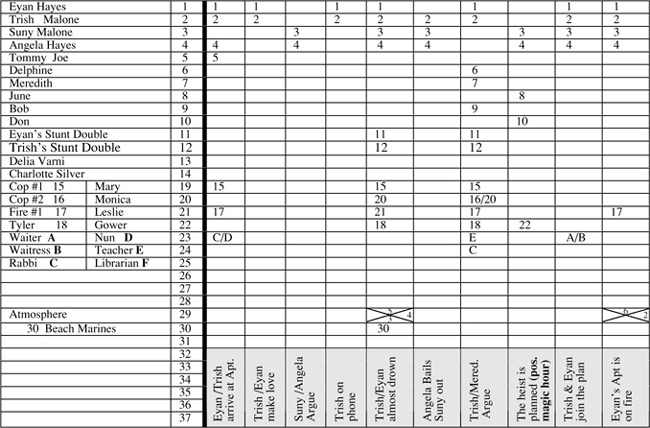

Primary characters of the story should be listed first. They are written on individual lines under character. (See Figure #4)

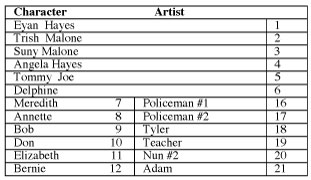

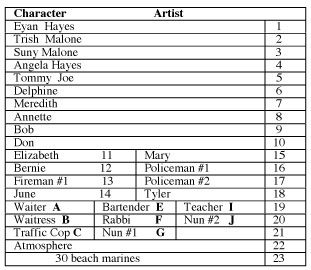

You will note that a number is automatically assigned to each characters’ name. This is the number that will be used to identify the character whenever the character is in a scene. Usually we list the main characters first, and work our way down the list to characters that have smaller speaking roles. All speaking roles are listed by character on the header.

Figure 3

Some screenplays have many more speaking roles than there are lines on the header. In those cases the header is altered accordingly. As the speaking roles get smaller, there is less of a likelihood of those smaller roles working together. Therefore we are able to re-number a portion of the header to adjust for this phenomena. (See Figure #5)

Figure 4

Figure 5

Once the cast of characters (speaking roles) has been penciled on the header, the next step is to create a legend for the bit roles. Each day the same silent bit character works, the actor portraying that character gets paid. If a bit character is assigned dialogue because of on set inspiration by the director on any day, and the project is a signatory to the Screen Actors Guild, the actor receives a “bump” in salary to that of a speaking role wage. And for every subsequent day worked by that bit character, whether or not he or she has dialogue, the actor continues to receive the higher wage.

A simple technique of creating a separate legend over four or five lines on the board works well for indicating bit characters. Each bit character is assigned a letter and the boxes corresponding to the numbers would reflect the letters of the bit characters needed for the scene. Also, select one numbered line for atmosphere required in a scene. (See Figure #6). The box on the strip corresponding to this number will indicate the number of atmosphere needed in the scene. Special atmosphere should be listed underneath.

Figure 6

Once the header has been prepared in this manner, the producer is ready to transfer the information from each breakdown page to individual strips. For purposes of this explanation we will look at the top part of the strips first.

You will notice that there is no specific space on the strip to indicate the scene number. This is because sometimes scene numbers will change, but the breakdown page numbers do not. However, it is much more efficient to indicate the scene number on each strip even if the scene number eventually changes. Therefore:

7. In the box on the strip opposite the line that has the words “character” and “artist,” write in the scene number as indicated from the breakdown page. (See Figure #7)

Figure 7

For the remainder of the strip, only information that is applicable to the ongoing creative producing decision-making process is taken from the breakdown page. Most important are those elements that appear in front of the camera, such as actors, atmosphere, animals and bit performers. Information regarding vehicles and props are not boarded unless they are important to, or indicative of, character in the story. As an example, in Hunter’s Blood I chose to board the Ford Bronco because this was a tradeoff product and it was needed on specific days. This required coordination with Ford as the Bronco was on loan for the picture. Also, it made sense creatively to board the Bronco since in the story it represented a safe place that the hunters were trying to get to while they were being hunted. It therefore served as a character in its own right.

It is not necessary for the producer to indicate on the board as to if a scene is to be shot M.O.S. This can be determined later during production meetings and will be of concern for the assistant director. During their own preparation the Property, Set Dressing and Wardrobe Departments will build on top of what is written in the script and flesh out their contribution to the visuals of the vision.

Figure #8 demonstrates the way the appropriate information is translated to each strip. Each bit of information has a direct correlation to each other bit of information and it permits the producer to see quickly the many choreographic permutations of production. Each of these permutations have a fiscal relationship to the creative process.

Figure 8

The following is taken from each breakdown page:

Figure #9 is a portion of a producer’s production board not yet broken down into shooting days, and it breaks the project down to the visual basics. The production board speaks to the producer. It indicates which scenes may be problematic and which scenes may work better if consolidated with other scenes. It tells the producer where money can be best used on the screen in telling the story. By reading the bottom summary in a continuous manner, the producer is able to see the action of the film unfold. A glance at the numbers denoting when specific cast members work can tell the producer how the Screen Actors Guild (also known as SAG) budget may lay out. Because the strips are of varying colors, a glance at the number of Exterior Day or Exterior Nights can highlight possible production problems which may occur on exterior locations.

Note that the header in Figure #9 also indicates the color of the strips and what they designate. This legend must be posted so others can understand the board without supervision.

Since breakdown pages are directly correlated to the structure of the screenplay, many times there will be more strips than there are spaces on a six or eight paneled production board. The screenplay may change continuously especially if the project adheres to the shoe fit the foot theory. Because each strip represents specific production logistics the project takes shape as shooting locations are secured and as the screenplay goes through various revisions. The strips may therefore change, and it is very likely there will be scenes that can be consolidated on a single strip.

Figure 9

The Production Board Eventually Becomes an Extension of the Creative Producer.

One example of scene consolidation (and one that is most common), are continuous dramatic action scenes in one setting that are intercut with other scenes. In this case it is acceptable to consolidate the scenes on one strip since the action and emotional content are continuous. In all probability the director will shoot all of each location’s scenes as if they were one scene because there are no dramatic changes in time which might call for a redress of setting, costume changes or emotional shifts of the characters. The top section of the strip might look like Figure #10, as it would reflect information from three separate breakdown pages.

Note that once the dramatic time in a location changes, a new strip must be prepared.

Many times a screenplay will call for the use of stock footage. Stock footage is already existing film (shot by other people) that is purchased for use in the project and licensed through a film footage library. Usually it involves imagery such as an airplane taking off or landing, or historical footage such as that used in the motion picture Forrest Gump. A production board must contain every scene whether the director shoots it or not. Therefore, a strip must represent stock footage as well. However, since it will not be part of the production’s obligation, a strip is prepared detailing in the summary what the scene is, and the words STOCK FOOTAGE written over the length of the strip. It is then placed in the production board upside down. (See Figure #9) The same is true if the project incorporates a second unit production team. Separate colored strips of those scenes to be shot via second unit should be prepared and included in the producer’s production board.

The preparation of the board raises the chicken and egg question that students always ask me. The practice of studio production and budget departments is to create the production board from the screenplay, and then create a budget from information that the board provides. This philosophy is based on the assumption that the project is writer driven rather than producer driven. In this case a screenplay written by a writer without any regard or knowledge of the logistics of production is given to a group of people none of whom have the responsibility for the creative result of the picture. They read the screenplay, prepare a board and create a budget, all without first getting input from either the producer or the director. At best this will lead to pre-production, production and post-production problems. At worst, this process will undermine the ability to creatively tell a story successfully. Elements that increase the cost of a project are primarily visual elements. In projects employing visuals to tell the story, the budget will reflect what is needed to create those visuals. If it is an historical project, or crosses various geographic regions, it will require a budget to support those requirements. If a project requires specific casting then the budget may reflect an increase to accommodate those casting elements. Therefore the producer must start out with a sensible budget plan and look at the screenplay from that perspective. Writers do not consider budget limitations or production elements when they work from their imaginations which is why the producer should employ the shoe fit the foot theory from the genesis of the project. (Besides, what makes a good narrative relies on the depth of the characters and what they say and feel, not just visual effects).

It is critical for the producer to know the choreographic elements of production through the production board process. Preparing the board gives the producer the opportunity to see any potential production problems or problems in the writing and make appropriate changes either in production or in the writing before these problems have an affect on the production process. The production board should be the producer’s tool and when interpreted by the producer will provide needed information for quick and easy creative decisions. Therefore the producer should be the first author of a production board (and budget). Every production is different and when the board is arranged and rearranged for the needs of production, the project takes on its own personality. The producer must be in synch with that personality.

I was given a licensing fee of $1.4 million dollars from the network for the television movie The Girl, the Gold Watch and Everything. As already mentioned, studios require the producer to be fiscally responsible by signing off on a budget. The studio production and budget departments prepared a board and budget from the screenplay. When the budget department came in with their budget of $2.6 million it was partially due to the special effects called for in the story. We wanted to “stop time” on exterior locations. The studio production department said the budget was too high due in part to what the script called for and I was instructed to have the screenplay rewritten to allow the effects to happen on interior soundstages in a simpler and less expensive fashion. But I had prepared my own board and budget and knew we could create the exterior effects through an experimental videotape transfer to film process that was the forerunner of high definition television. I knew that by using this experimental process the special effects would cost 1/10th of what they might cost if they were attempted entirely on film. It could also be done in half the time. I told the studio that the effects would cost no more than $30,000, and showed them the item in the budget that I had prepared for the project. My executive producers backed me all the way on this issue and we went ahead and made the film. The special effects did cost $30,000 and the picture was finally produced for $1,360,000—below the licensing fee—and the studio suits were astounded when they saw the results onscreen.

The production board is the producer’s bible. It is the map that allows the producer to make instant creative decisions in relation to the budget and the visual needs of the project. It allows the producer to examine the choreography of production and see the creation of the visuals from a fiscal point of view. There is no mystery in the preparation of a production board. The mystery lies in the laying out of the board. (This will be addressed in Chapter 11.)

“The film business is simply that—a business. Like any Fortune 100 business, it is driven by creativity and product with the common denominator being cost and profit. Throughout my career to date, I have been fortunate enough to have enjoyed a creative and collaborative experience with some of today’s hardest driving, most creative and knowledgeable producers and directors (James Cameron, Danny DeVito, Michael Douglas, Peter Guber, Gale Anne Hurd, Mark Johnson, Barry Levinson and Joel Silver to name a few)…Producers often find themselves pitted against, on one side, the studio or bankers who put up the funds to make the film, and on the other—their director. Producers must walk a fine line between guarding the creative vision, guarding the budget and maintaining the relationships and confidence of the studio, distributor, bankers, financiers and completion bond companies. At the end of the day we must remember that the film business creates entertainment, enjoyment, visual dimension and expressionism—but is a business that needs profit to maintain its existence. Art, on the other hand, is the guy down the street who owns the pawn shop.”

—Steven R. Benson, Visual Effects Supervisor, Producer, Studio Executive, Austin Powers, International Man of Mystery; Aliens, The Crow I, The Crow II, The Jewel of the Nile, Sniper, Commando, Prefontaine, Spy Hard

1 The computer programs do not make decisions. They merely look for like notations. The producer makes creative decisions while working on a breakdown: i.e. number and gender of atmosphere, characters in scenes who may not speak in the scene but appear elsewhere in the script, etc.