Aquatic Exercises

SWIMMING

Swimming, considered with regard to the movements that it requires, is useful in promoting great muscular strength; but the good effects are not solely the result of the exercise that the muscles receive, but partly of the medium in which the body is moved. But the considerable increase of general force, and the tranquillizing of the nervous system produced by swimming, arise chiefly from this, that the movements, in consequence of the cold and dense medium in which they take place, occasion no loss.fn1

It is easy to conceive of what utility swimming must be, where the very high state of the atmospheric temperature requires inactivity in consequence of the excessive loss caused by the slightest movement. It then becomes an exceedingly valuable resource, the only one, indeed, by which muscular weakness can be remedied, and the energy of the vital functions maintained. We must therefore regard swimming as one of the most beneficial exercises that can be taken in summer.

The ancients, particularly the Athenians, regarded swimming as indispensable; and when they wished to designate a man who was fit for nothing, they used to say, ‘he cannot even swim’, or ‘he can neither read nor swim’. At many seaports, the art of swimming is almost indispensable; and the sailors’ children are as familiar with the water as with the air. Copenhagen is perhaps the only place where sailors are trained by rules of art; and there, this exercise is more general and in greater perfection than elsewhere. It may here be observed, that it is not fear alone that prevents a man swimming. Swimming is an art that must be learnt; and fear is only an obstacle to the learning.

PREPARATORY INSTRUCTIONS AS TO ATTITUDE AND ACTION IN SWIMMING

As it is on the movements of the limbs, and a certain attitude of the body, that the power of swimming depends, its first principles may evidently be acquired out of the water.

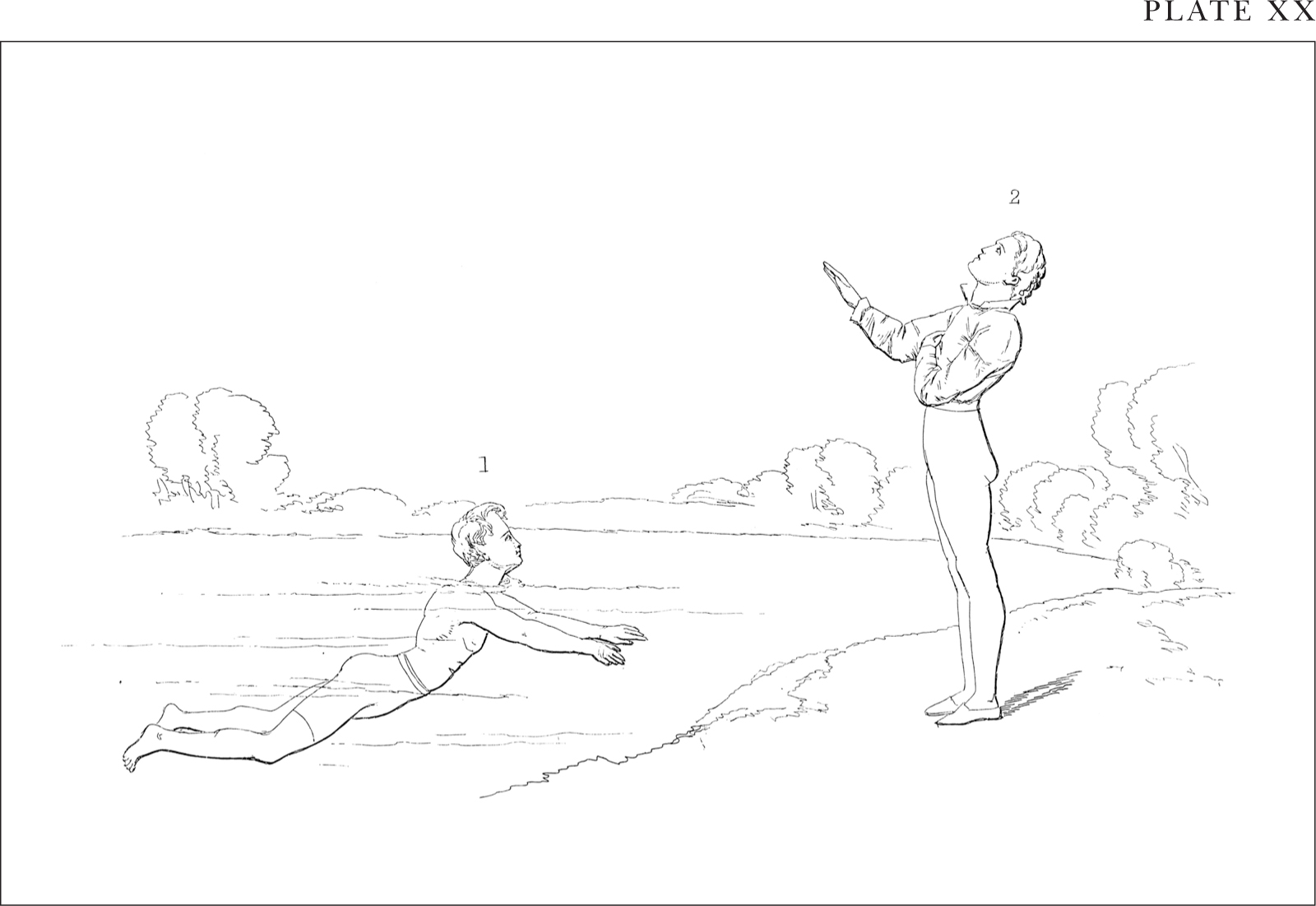

Attitude

The head must be drawn back, and the chin elevated, the breast projected, and the back hollowed and kept steady (Plate XX. figs. 1 and 2). The head can scarcely be thrown too much back, or the back too much hollowed. Those who do otherwise, swim with their feet near the surface of the water, instead of having them two or three feet deep.

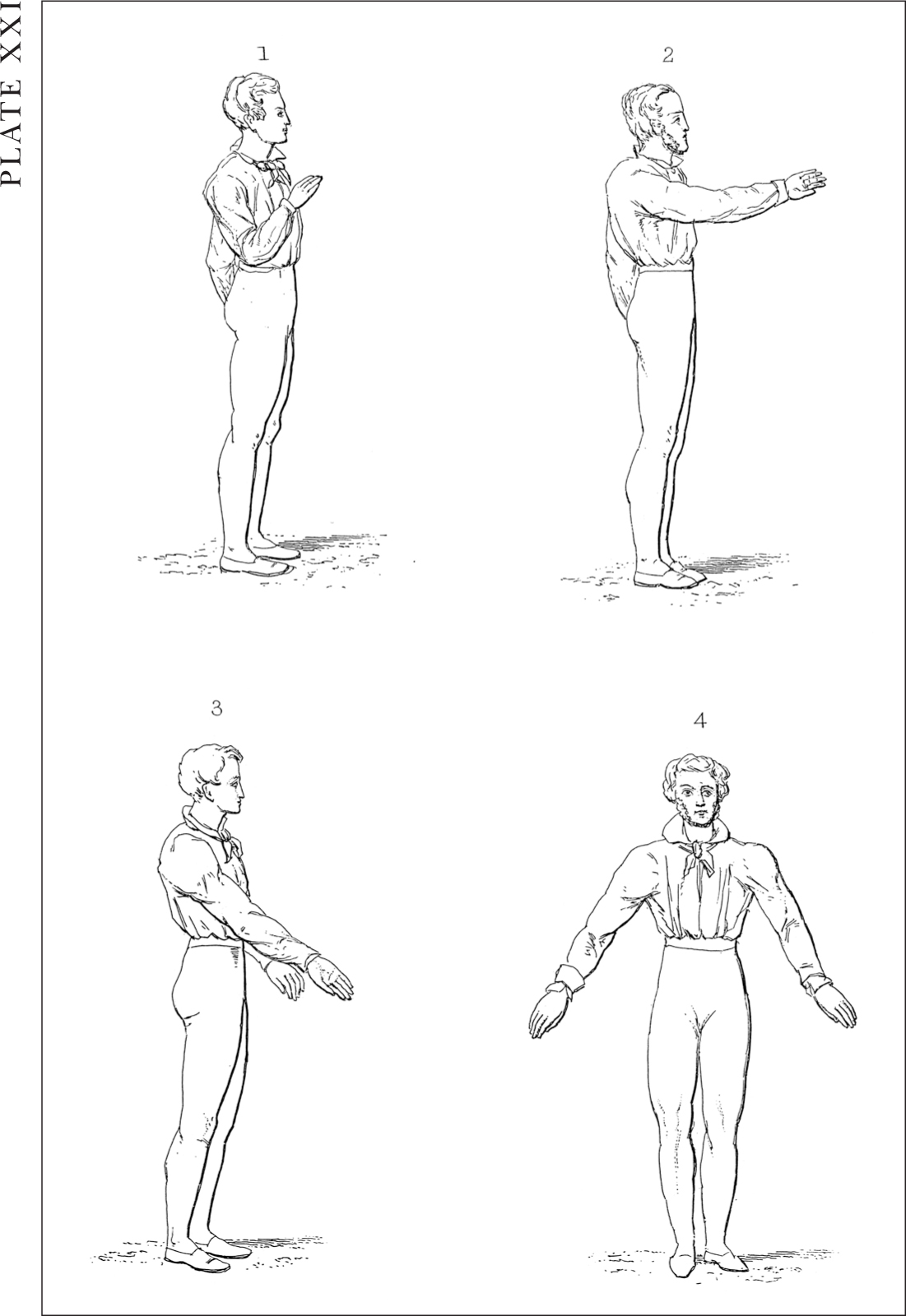

Action of the Hands

In the proper position of the hands, the fingers must be kept close, with the thumbs by the edge of the fore-fingers; and the hands made concave on the inside, though not so much as to diminish their size and power in swimming. The hands, thus formed, should be placed just before the breast, the wrist touching it, and the fingers pointing forward (Plate XXI. fig. 1).

The first elevation is formed by raising the ends of the fingers three or four inches higher than the rest of the hands. The second, by raising the outer edge of the hand two or three inches higher than the inner edge.

The formation of the hands, their first position, and their two modes of elevation, being clearly understood, the forward stroke is next made, by projecting them in that direction to their utmost extent, employing therein their first elevation, in order to produce buoyancy, but taking care the fingers do not break the surface of the water (Plate XXI. fig. 2). In the outward stroke of the hands, the second elevation must be employed; and, in it, they must sweep downward and outward as low as – but at a distance from – the hips, both laterally and anteriorly (Plate XXI. figs. 3 and 4).

The retraction of the hands is effected by bringing the arms closer to the sides, bending the elbow joints upward and the wrists downward, so that the hands hang down, while the arms are raising them to the first position, the action of the hands being gentle and easy. In the three movements just described, one arm may be exercised at a time, until each is accustomed to the action.

Action of the Feet

In drawing up the legs, the knees must be inclined inward, and the soles of the feet outward (Plate XXII. fig. 1). The throwing out of the feet should be to the extent of the legs, as widely from each other as possible (Plate XXII. fig. 2). The bringing down of the legs must be done briskly, until they come close together. In drawing up the legs, there is a loss of power; in throwing out the legs, there is a gain equal to that loss; and in bringing down the legs, there is an evident gain.

The arms and legs should act alternately; the arms descending while the legs are rising (Plate XXII. fig. 3); and, oppositely, the arms rising while the legs are descending (Plate XXII. fig. 4). Thus the action of both is unceasingly interchanged; and, until great facility in this interchange is effected, no one can swim smoothly, or keep the body in one continued progressive motion. In practising the action of the legs, one hand may rest on the top of a chair, while the opposite leg is exercised. When both the arms and the legs are separately accustomed to the action, the arm and leg of the same side may be exercised together.

PLACE AND TIME fOr SWIMMING

Place

Of all places for swimming, the sea is the best; running waters next; and ponds the worst. In these a particular spot should be chosen, where there is not much stream, and which is known to be safe.

The swimmer should make sure that the bottom is not out of his depth; and, on this subject, he cannot be too cautious when he has no one with him who knows the place. If capable of diving, he should ascertain if the water be sufficiently deep for that purpose, otherwise, he may injure himself against the bottom. The bottom should be of gravel, or smooth stones, and free from holes, so that he may be in no danger of sinking in the mud or wounding the feet. Of weeds he must beware; for if his feet get entangled among them, no aid, even if near, may be able to extricate him.

Time

The best season of the year for swimming is during the months of May, June, July, and August. Morning before breakfast – that is to say, from seven till eight o’clock – is the time. In the evening, the hair is not perfectly dried, and coryza is sometimes the consequence. Bathing during rain is bad, for it chills the water, and, by wetting the clothes, endangers catching cold. In practising swimming during those hours of the day when the heat of the sun is felt most sensibly, if the hair be thick, it should be kept constantly wet; if the head be bald, it must be covered with a handkerchief, and frequently wetted.

It is advisable not to enter the water before digestion is finished. The danger in this case arises less from the violent movements which generally disorder digestion, than from the impression produced by the medium in which these movements are executed. It is not less so when very hot, or quite cold. It is wrong to enter the water in a perspiration, however trifling it may be. After violent exercises, it is better to wash and employ friction than to bathe. Persons of plethoric temperament, who are subject to periodical evacuations, such as haemorrhoids, or even to cutaneous eruptions, will do well to abstain from swimming during the appearance of these afflictions.

Dress

Every swimmer should use short drawers, and might, in particular places, use canvas slippers. It is even of great importance to be able to swim in jacket and trousers.

Aids

The aid of the hand is much preferable to corks or bladders, because it can be withdrawn gradually and insensibly. With this view, a grown-up person may take the learner in his arms, carry him into the water breast high, place him nearly flat upon it, support him by one hand under the breast, and direct him as to attitude and action. If the support of the hand be very gradually withdrawn, the swimmer will, in the course of the first ten days, find it quite unnecessary. When the aid of the hand cannot be obtained, inflated membranes or corks may be employed. The only argument for their use is, that attitude and action may be perfected while the body is thus supported; and that, with some contrivance, they also may gradually be laid aside, though by no means so easily as the hand.

The best mode of employing corks is to choose a piece about a foot long, and six or seven inches broad; to fasten a band across the middle of it; to place it on the back, so that the upper end may come between the shoulder-blades, where the edge may be rounded; and to tie the band over the breast. Over this, several other pieces of cork, each smaller than the preceding, may be fixed, so that, as the swimmer improves, he may leave them off one by one. Even with all these aids, the young swimmer should never venture out of his depth, if he cannot swim without them.

Cramp

As to cramp, those chiefly are liable to it who plunge into the water when they are heated, who remain in it till they are benumbed with cold, or who exhaust themselves by violent exercise. Persons subject to this affliction must be careful with regard to the selection of the place where they bathe, if they are not sufficiently skilful in swimming to vary their attitudes, and dispense instantly with the use of the limb attacked by cramp. Even when this does occur, the skilful swimmer knows how to reach the shore by the aid of the limbs which are unaffected, while the uninstructed one is liable to be drowned.

If attacked in this way in the leg, the swimmer must strike out the limb with all his strength, thrusting the heel downward and drawing the toes upward, notwithstanding the momentary pain it may occasion; or he may immediately turn flat on his back, and jerk out the affected limb in the air, taking care not to elevate it so high as greatly to disturb the balance of the body. If this does not succeed, he must paddle ashore with his hands, or keep himself afloat by their aid, until assistance can reach him. Should he even be unable to float on his back, he must put himself in the upright position, and keep his head above the surface by merely striking the water downward with his hands at the hips, without any assistance from the legs.

PROCEDURE WHEN IN THE WATER, AND USUAL MODE OF FRONT SWIMMING

Entering the Water

Instructors should never force young swimmers to leap into the water reluctantly. It would be advisable for delicate persons, especially when they intend to plunge in, to put a little cotton steeped in oil, and afterwards pressed, in their ears, before entering the water. This precaution will prevent irritation of the organ of hearing. In entering, the head should be wetted first, either by plunging in head foremost, or by pouring water on it, in order to prevent the pressure of the water driving up the blood into the head too quickly, and increasing congestion. The swimmer should next advance, by a clear shelving shore or bank, where he has ascertained the depth by plumbing or otherwise, till the water reaches his breast; should turn towards the place of entrance; and, having inflated his breast, lay it upon the water, suffering that to rise to his chin, the lips being closed.

Buoyancy in the Water

The head alone is specifically heavier than salt water. Even the legs and arms are specifically lighter; and the trunk is still more so. Thus the body cannot sink in salt water, even if the lungs were filled, except owing to the excessive specific gravity of the head.

Not only the head, but the legs and arms, are specifically heavier than fresh water; but still the hollowness of the trunk renders the body altogether too light to sink wholly under water, so that some part remains above until the lungs become filled. In general, when the human body is immersed, one-eleventh of its weight remains above the surface in fresh water, and one-tenth in salt water.

In salt water, therefore, a person throwing himself on his back, and extending his arms, may easily lie so as to keep his mouth and nostrils free for breathing; and, by a small motion of the hand, may prevent turning, if he perceive any tendency to it. In fresh water, a man cannot long continue in that situation, except by the action of his hands; and if no such action be employed, the legs and lower part of the body will gradually sink into an upright position, the hollow of the breast keeping the head uppermost. If, however, in this position, the head be kept upright above the shoulders, as in standing on the ground, the immersion, owing to the weight of the part of the head out of the water, will reach above the mouth and nostrils, perhaps a little above the eyes. On the contrary, in the same position, if the head be leaned back, so that the face is turned upward, the back part of the head has its weight supported by the water, and the face will rise an inch higher at every inspiration, and will sink as much at every expiration, but never so low that the water can come over the mouth.

For all these reasons, though the impetus given by the fall of the body into water occasions its sinking to a depth proportioned to the force of the descent, its natural buoyancy soon impels it again to the surface, where, after a few oscillations up and down, it settles with the head free.

Unfortunately, ignorant people stretch the arms out to grasp at anything or nothing, and thereby keep the head under; for the arms and head, together exceeding in weight one-tenth of the body, cannot remain above the surface at the same time. The buoyancy of the trunk, then and then only, occasions the head and shoulders to sink, the ridge of the bent back becoming the portion exposed; and, in this attitude, water is swallowed, by which the specifie gravity is increased, and the body settles to the bottom. It is, therefore, most important to the safety of the inexperienced to be firmly convinced that the body naturally floats.

To satisfy the beginner of the truth of this, Dr Franklin advises him to choose a place where clear water deepens gradually, to walk into it till it is up to his breast, to turn his face to the shore, and to throw an egg into the water between him and it – so deep that he cannot fetch it up but by diving. To encourage him to take it up, he must reflect that his progress will be from deep to shallow water, and that at any time he may, by bringing his legs under him, and standing on the bottom, raise his head far above the water. He must then plunge under it, having his eyes open, before as well as after going under; throw himself towards the egg, and endeavour, by the action of his hands and feet against the water, to get forward till within reach of it. In this attempt, he will find that the water brings him up against his inclination, that it is not so easy to sink as he imagined, and that he cannot, but by force, get down to the egg. Thus he feels the power of water to support him, and learns to confide in that power; while his endeavours to overcome it, and reach the egg, teach him the manner of acting on the water with his feet and hands, as he afterwards must in swimming, in order to support his head higher above the water, or to go forward through it.

If, then, any person, however unacquainted with swimming, will hold himself perfectly still and upright, as if standing with his head somewhat thrown back so as to rest on the surface, his face will remain above the water, and he will enjoy full freedom of breathing. To do this most effectually, the head must be so far thrown back that the chin is higher than the forehead, the breast inflated, the back quite hollow, and the hands and arms kept under water. If these directions be carefully observed, the face will float above the water, and the body will settle in a diagonal direction (Plate XXIII. fig. 1).

In this case, the only difficulty is to preserve the balance of the body. This is secured, as described by Bernardi, by extending the arms laterally under the surface of the water, with the legs separated, the one to the front and the other behind: thus presenting resistance to any tendency of the body to incline to either side, forward or backward. This posture may be preserved any length of time (Plate XXIII. fig. 2).

The Abbé Paul Moccia, who lived in Naples in 1760, perceived, at the age of fifty, that he could never entirely cover himself in the water. He weighed three hundred pounds (Italian weight), but being very fat, he lost at least thirty pounds in the water. Robertson had just made his experiments on the specific weight of man; and everybody was then occupied with the Abbé, who could walk in the water with nearly half his body out of it.

Attitude and Action in the Water

The swimmer having, by all the preceding means, acquired confidence, may now practise the instructions already given on attitude and action in swimming: or he may first proceed with the system of Bernardi, which immediately follows. As the former have already been given in ample detail, there is nothing new here to be added respecting them, except that, while the attitude is correct, the limbs must be exercised calmly, and free from all hurry and trepidation, the breath being held, and the breast kept inflated, while a few strokes are made. In swimming in the usual way, there is, first, extension, flexion, abduction and adduction of the members; secondly, almost constant dilation of the chest, to diminish the mobility of the point of attachment of the muscles which are inserted in the elastic sides of this cavity, and to render the body specifically lighter; thirdly, constant action of the muscles of the back part of the neck, to raise the head, which is relatively very heavy, and to allow the air free entrance to the lungs.

Respiration in Swimming

If the breath is drawn at the moment when the swimmer strikes out with the legs, instead of when the body is elevated by the hands descending towards the hips, the head partially sinks, the face is driven against the water, and the mouth becomes filled. If, on the contrary, the breath is drawn when the body is elevated by the hands descending towards the hips (when the progress of the body forward consequently ceases, and when the face is no longer driven against the water, but is elevated above the surface) then, not only cannot the water enter, but if the mouth were at other times even with, or partly under the surface, no water could enter it, as the air, at such times, driven outward between the lips, would effectually prevent it. The breath should accordingly be expired while the body, at the next stroke, is sent forward by the action of the legs.

Coming out of the Water

Too much fatigue in the water weakens the strength and presence of mind necessary to avoid accidents. A person who is fatigued, and remains there without motion, soon becomes weak and chilly. As soon as he feels fatigued, chill, or numb, he should quit the water, and dry and dress himself as quickly as possible. Friction, previous to dressing, drives the blood over every part of the body, creates an agreeable glow, and strengthens the joints and muscles.

UPRIGHT SWIMMING

Bernardi’s System

The principal reasons given by Bernardi for recommending the upright position in swimming are: its conformity to the accustomed movement of the limbs; the freedom it gives to the hands and arms, by which any impediment may be removed, or any offered aid readily laid hold of; vision all round; a much greater facility of breathing; and lastly, that much less of the body is exposed to the risk of being laid hold of by persons struggling in the water.

The less we alter our method of advancing in the water from what is habitual to us on shore, the more easy do we find a continued exercise of it. The most important consequence of this is that, though a person swimming in an upright posture advances more slowly, he is able to continue his course much longer; and certainly nothing can be more beneficial to a swimmer than whatever tends to husband his strength, and to enable him to remain long in the water with safety.

Bernardi’s primary object is to enable the pupil to float in an upright posture, and to feel confidence in the buoyancy of his body. He accordingly supports the pupil under the shoulders until he floats tranquilly with the head and part of the neck above the surface, the arms being stretched out horizontally under water. From time to time, the supporting arm is removed, but again restored, so as never to suffer the head to sink, which would disturb the growing confidence, and give rise to efforts destructive of the success of the lesson. In this early stage, the unsteadiness of the body is the chief difficulty to be overcome.

The head is the great regulator of our movements in water. Its smallest inclination to either side instantly operates on the whole body; and, if not corrected, throws it into a horizontal posture. The pupil must, therefore, restore any disturbance of equilibrium by a cautious movement of the head alone in an opposite direction. This first lesson being familiarized by practice, he is taught the use of the legs and arms for balancing the body in the water. One leg being stretched forward, the other backward, and the arms laterally, he soon finds himself steadily sustained, and independent of further aid in floating.

When these first steps have been gained, the sweeping semicircular motion of the arms is shown. This is practised slowly, without motion forward, until attained with precision. After this, a slight inclination of the body from the upright position occasions its advancing. The motion of striking with the legs is added in the same measured manner; so that the pupil is not perplexed by the acquisition of more than one thing at a time. In this method, the motions of both arms and legs differ from those we have so carefully described, only in so far as they are modified by a more upright position. It is optional, therefore, with the reader, to practise either method. The general principles of both are now before him.

The upright position a little inclined backward (which, like every other change of posture, must be done deliberately, by the corresponding movement of the head), reversing in this case the motion of the arms, and striking the flat part of the foot down and a little forward, gives the motion backward, which is performed with greater ease than when the body is laid horizontally on the back. According to this system, Bernardi says, a swimmer ought, at every stroke, to urge himself forward a distance equal to the length of his body. A good swimmer ought to make about three miles an hour. A good day’s journey may thus be achieved, if the strength be used with due discretion, and the swimmer be familiar with the various means by which it may be recruited.

Of Bernardi’s successful practice, he says:

Having been appointed to instruct the youths of the Royal Naval Academy of Naples in the art of swimming, a trial of the proficiency of the pupils took place, under the inspection of a number of people assembled on the shore for that purpose, on the tenth day of their instruction. A twelve-oared boat attended the progress of the pupils, from motives of precaution. They swam so far out in the bay, that at length the heads of the young men could with difficulty be discerned with the naked eye; and the Major-General of Marine, Forteguerri, for whose inspection the exhibition was intended, expressed serious apprehensions for their safety. Upon their return to the shore, the young men, however, assured him that they felt so little exhausted as to be willing immediately to repeat the exertion.

An official report on the subject has also been drawn up by commission (appointed by the Neapolitan government), after devoting a month to the investigation of Bernardi’s plan; and it states as follows:

Firstly, It has been established by the experience of more than a hundred persons of different bodily constitutions, that the human body is lighter than water, and consequently will float by nature; but that the art of swimming must be acquired, to render that privilege useful.

Secondly, That Bernardi’s system is new, in so far as it is founded on the principle of husbanding the strength, and rendering the power of recruiting it easy. The speed, according to the new method, is no doubt diminished; but security is much more important than speed; and the new plan is not exclusive of the old, when occasions require great effort.

Thirdly, That the new method is sooner learnt than the old, to the extent of advancing a pupil in one day as far as a month’s instruction on the old plan.

Treading Water

This differs little from the system just described. In it, the position is upright; but progression is obtained by the action of the legs alone. There is little power in this method of swimming: but it may be very useful in rescuing drowning persons.

The arms should be folded across, below the breast, or compressed against the hips, and the legs employed as in front swimming, except as to time and extent. They should perform their action in half the usual time, or two strokes should be taken in the time of one; because, acting perpendicularly, each stroke would otherwise raise the swimmer too much, and he would sink too low between the strokes, were they not quickly to follow each other. They should also work in about two-thirds of the usual space, preserving the upper or stronger, and omitting the lower or weaker, part of the stroke.

There is, however, another mode of treading water, in which the thighs are separated, and the legs slightly bent, or curved together, as in a half-sitting posture. Here the legs are used alternately, so that, while one remains more contracted, the other, less so, describes a circle. By this method, the swimmer does not seem to hop in the water, but remains nearly at the same height. Plate XXIII. fig. 3 represents both these methods, and shows their peculiar adaptation to relieve drowning persons.

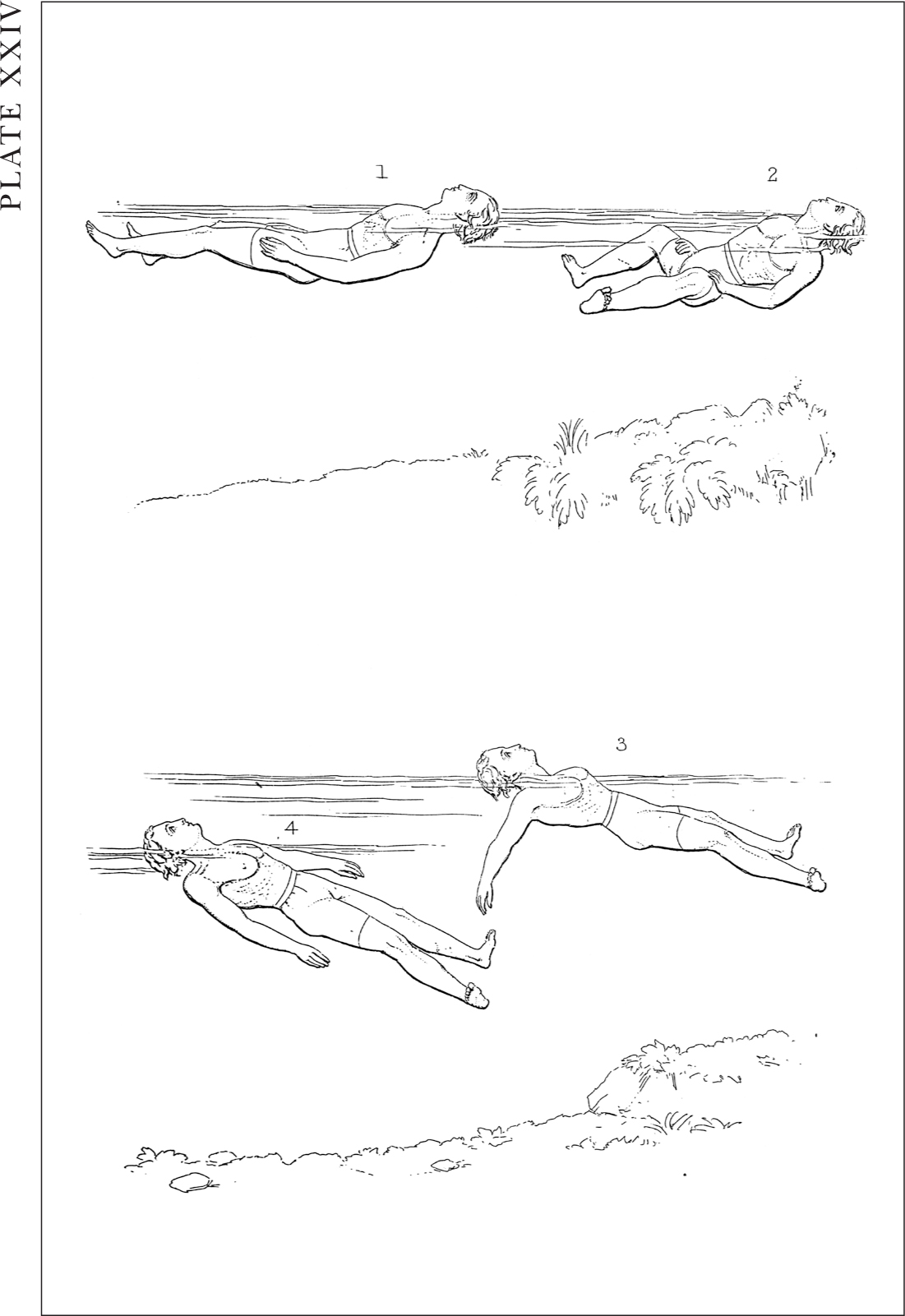

BACK SWIMMING

In swimming on the back, the action of the thoracic members is weaker, because the swimmer can support himself on the water without their assistance. The muscular contractions take place principally in the muscles of the abdominal members, and in those of the anterior part of the neck. Though little calculated for progression, it is the easiest of all methods, because, much of the head being immersed, little effort is required for support. For this purpose, the swimmer must lie down gently upon the water; the body extended; the head kept in a line with it, so that the back and much of the upper part of the head may be immersed; the head and breast must remain perfectly unagitated by the action of the legs; the hand laid on the thighs (Plate XXIV. fig. 1) and the legs employed as in front swimming, care being taken that the knees do not rise out of the water (Plate XXIV. fig. 2). The arms may, however, be used in various ways in swimming on the back.

In the method called winging, the arms are extended till in a line with each other; they must then be struck down to the thighs, with the palms turned in that direction, and the thumbs inclining downward to increase the buoyancy (Plate XXIV. fig. 3); the palms must then be moved edgewise, and the arms elevated as before (Plate XXIV. fig. 4), and so on, repeating the same actions. The legs should throughout make one stroke as the arms are struck down, and another as they are elevated. The other mode, called finning, differs from this only in the stroke of the arms being shorter, and made in the same time as that of the legs.

In back swimming, the body should be extended after each stroke, and long pauses made between these. The act of passing from front to back, or back to front swimming, must always be performed immediately after throwing out the feet. To turn from the breast to the back, the legs must be raised forward, and the head thrown backward, until the body is in a right position. To turn from the back to the breast, the legs must be dropped, and the body thrown forward on the breast.

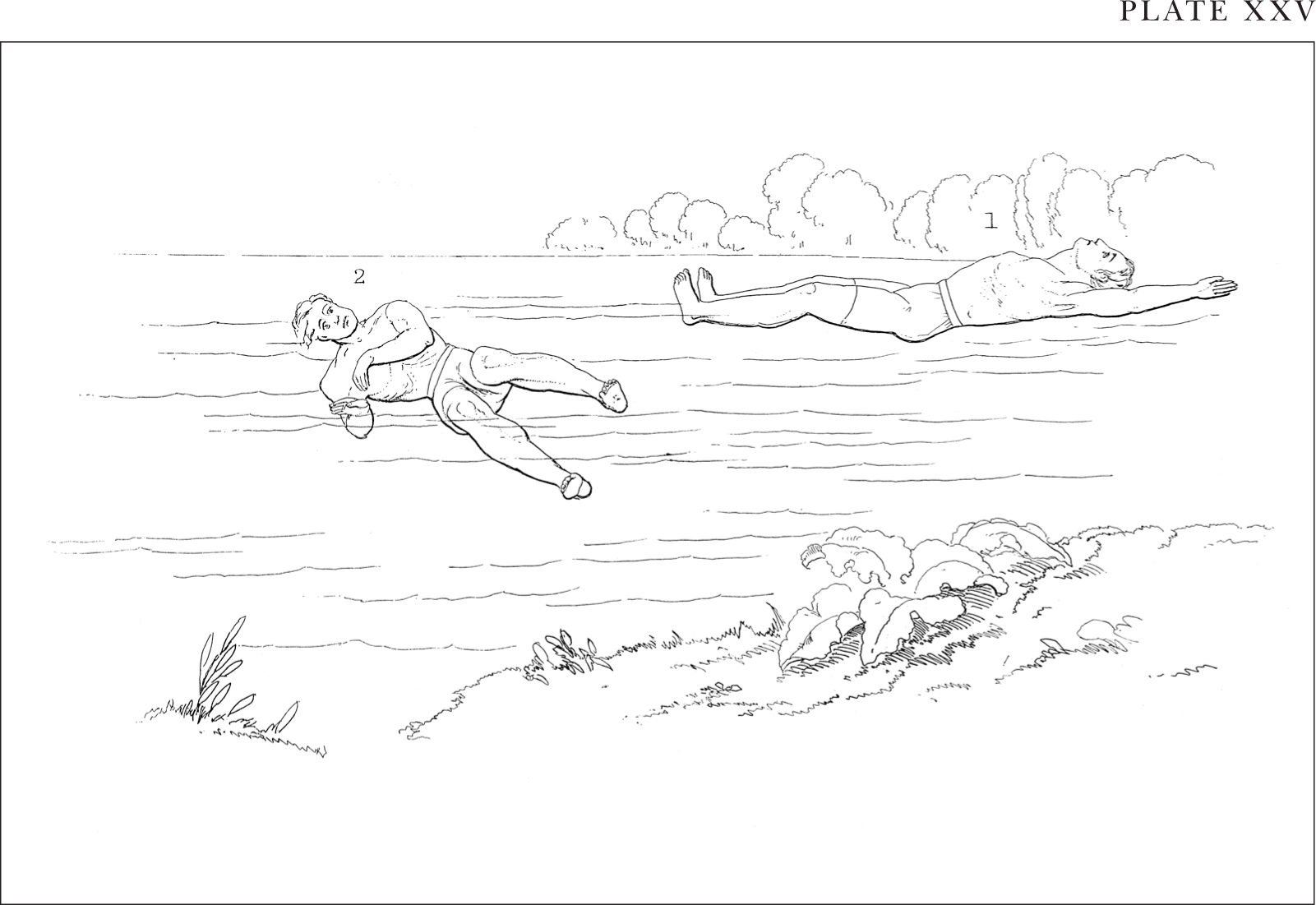

FLOATING

Floating is properly a transition from swimming on the back. To effect it, it is necessary, while the legs are gently exercising, to extend the arms as far as possible beyond the head, equidistant from, and parallel with, its sides, but never rising above the surface; to immerse the head rather deeply, and elevate the chin more than the forehead; to inflate the chest while taking this position, and so to keep it as much as possible; and to cease the action of the legs, and put the feet together (Plate XXV. fig. 1). The swimmer will thus be able to float, rising a little with every inspiration, and falling with every expiration. Should the feet descend, the loins may be hollowed.

SIDE SWIMMING

For this purpose, the body may be turned either upon the right or left side: the feet must perform their usual motions: the arms also require peculiar guidance. In lowering the left, and elevating the right side, the swimmer must strike forward with the left hand, and sideways with the right; the back of the latter being front instead of upward, and the thumb side of the hand downward to serve as an oar. In turning on the right side, the swimmer must strike out with the right hand, and use the left as an oar. In both cases, the lower arm stretches itself out quickly, at the same time that the feet are striking; and the upper arm strikes at the same time that the feet are impelling, the hand of the latter arm beginning its stroke on a level with the head. While this hand is again brought forward, and the feet are contracted, the lower hand is drawn back towards the breast, rather to sustain than to impel (Plate XXV. fig. 2). As side swimming presents to the water a smaller surface than front swimming, it is preferable when rapidity is necessary. But, though generally adopted when it is required to pass over a short distance with rapidity, it is much more fatiguing than the preceding methods.

PLUNGING

In the leap to plunge, the legs must be kept together, the arms close, and the plunge made either with the feet or the head foremost. With the feet foremost, they must be kept together, and the body inclined backward. With the head foremost, the methods vary.

In the deep plunge, which is used where it is known that there is depth of water, the swimmer has his arms outstretched, his knees bent, and his body leant forward (Plate XXVI. fig. 1), till the head descends nearly to the feet, when the spine and knees are extended. This plunge may be made without the slightest noise. When the swimmer rises to the surface, he must not open his mouth before previously repelling the water.

In the flat plunge, which is used in shallow water, or where the depth is unknown, and which can be made only from a small height, the swimmer must fling himself forward, in order to extend the line of the plunge as much as possible under the surface of the water; and, as soon as he touches it, he must keep his head up, his back hollow, and his hands stretched forward, flat and inclined upward. He will thus dart forward a considerable way close under the surface, so that his head will reach it before the impulse ceases to operate (Plate XXVI. fig. 2).

DIVING

The swimmer may prepare for diving by taking a slow and full inspiration, letting himself sink gently into the water, and expelling the breath by degrees, when the heart begins to beat strongly. In order to descend in diving, the head must be bent forward upon the breast; the back made round; and the legs thrown out with greater vigour than usual; but the arms and hands, instead of being struck forward as in swimming, must move rather backward, or come out lower, and pass more behind (Plate XXVII. fig. 1). The eyes should, meanwhile, be kept open, as, if the water be clear, it enables the diver to ascertain its depth, and see whatever lies at the bottom; and, when he has obtained a perpendicular position, he should extend his hands like feelers.

To move forward, the head must be raised, and the back straightened a little. Still, in swimming between top and bottom, the head must be kept a little downward, and the feet be thrown out a little higher than when swimming on the surface (Plate XXVII. fig. 2); and if the swimmer thinks that he approaches too near the surface, he must press the palms upward. To ascend, the chin must be held up, the back made concave, the hands struck out high, and brought briskly down (Plate XXVII. fig. 3).

THRUSTING

This is a transition from front swimming, in which the attitude and motions of the feet are still the same, but those of the hands very different. One arm, the right for instance, is lifted entirely out of the water, thrust forward as much as possible, and, when at the utmost stretch, let fall, with the hand hollowed, into the water, which it grasps or pulls towards the swimmer in its return transversely towards the opposite arm-pit. While the right arm is thus stretched forth, the left, with the hand expanded, describes a small circle to sustain the body (Plate XXVIII. fig. 1), and, while the right arm pulls towards the swimmer, the left, in a widely-described circle, is carried rapidly under the breast, towards the hip (Plate XXVIII. fig. 2).

When the left arm has completed these movements, it, in its turn, is lifted from the water, stretched forward, and pulled back, the right arm describing first the smaller, then the larger circle. The feet make their movements during the describing of the larger circle. The thrust requires much practice; but, when well acquired, it not only relieves the swimmer, but enables him to make great advance in the water, and is applicable to cases where rapidity is required for a short distance.

SPRINGING

Some swimmers, at every stroke, raise not only their neck and shoulders, but breast and body, out of the water. This, when habitual, exhausts without any useful purpose. As an occasional effort, however, it may be useful in seizing objects above; and it may then best be performed by the swimmer drawing his feet as close as possible under his body, stretching his hands forward, and, with both feet and hands, striking the water strongly, so as to throw himself out of it as high as the hips.

ONE-ARM SWIMMING

Here the swimmer must be more erect than usual, hold his head more backward, and use the legs and arm more quickly and powerfully. The arm, at its full extent, must be struck out rather across the body, and brought down before, and the breast kept inflated. This mode of swimming is best adapted for assisting persons who are drowning, and should be frequently practised – the learner carrying first under, then over the water, a weight of a few pounds.

In assisting drowning persons, however, great care should be taken to avoid being caught hold of by them. They should be approached from behind, and driven before, or drawn after the swimmer to the shore, by the intervention, if possible, of anything that may be at hand, and if nothing be at hand, by means of their hair; and they should, if possible, be got on their backs. Should they attempt to seize the swimmer, he must cast them loose immediately; and, if seized, drop them to the bottom, from whence they will endeavour to rise to the surface.

Two swimmers treading water may assist a drowning person by seizing him, one under each arm, and carrying him along with his head above water, and his body and limbs stretched out and motionless.

FEATS IN SWIMMING

Men have been known to swim in their clothes a distance of 4,000 feet.

Others have performed 2,200 feet in twenty-nine minutes.

Some learn to dive and bring out of the water burdens as heavy as a man.fn2