Chapter 4

Incongruity

“Taste is the smiling surface of a lake whose depths are great, impenetrable and cold,” wrote the architectural historian Sir John Summerson. “At unpredictable moments the waters divide, the smooth surface vanishes and the depths are revealed. But only for a moment and the storm leaves nothing but ripples on the fresh, icy surface.”1 Summerson offered this metaphor as his conclusion to an essay on William Butterfield, the nineteenth-century architect whose work had seemed (and continues to seem) more impervious to sympathetic understanding than the work of his Victorian contemporaries. “People of taste screw up their faces at the architecture of William Butterfield,” Summerson conceded, but he believed the key to understanding was to inquire more deeply into the deliberate ugliness of Butterfield’s architecture.2 With characteristically awkward proportions, irregular composition, discordant colors, and a generalized coarseness, all of Butterfield’s works (churches for the most part) were “to a greater or lesser degree ugly.”3 This ugliness, though, was in Summerson’s view purposeful, part of a “singular attraction on the part of some painters, architects, and writers towards ugliness” in the middle decades of the nineteenth century; an attraction prompted by nothing less than a desire to overthrow the restrictions of taste that surrounded them. “The truth is that these people wanted, needed, craved ugliness.”4

The sympathetic understanding of Butterfield’s ugly architecture required not an affinity of taste, then, but a recognition of the temporal situation of his architecture, the recognition of an opposition between one historical setting and another that preceded and threatened to overshadow it.

Just imagine yourself living in late Georgian London—yes, living in it, not just reading about it or enjoying the melancholy of its time-washed fragments. Imagine a city in which every street is a Gower Street, in which the “great” buildings are by smooth Mr. Wilkins, dull Mr. Smirke or facetious Mr. Nash. Imagine the unbearable oppressiveness of a landscape in which such architecture represents the emotional ceiling. . . . Across the hideous streets, the flaccid stucco, the flimsy railings and the six or seven million chimney-pots [the young architect] sees the vision of an architecture which is hard, muscular, fearless, contemptuous alike of the drawing-room and the drawing-board—which is full of everything the architecture around him negates.5

This ugliness is full of motive, an assertion of the future of possibility against the enclosures of an encompassing past; not, though, in the modernist sense of novelty—for Butterfield was one of those scrupulous gothic revivalists—but in the sense of opening a seam in a civic fabric that had covered society for too long. Such a challenge could be pursued in diverse materials of culture, in any of the arts and in political economy as well, but Summerson identified a role for architecture in giving visceral “hammerblows against ‘taste.’ ”6 It might be argued, and not incorrectly, that much of this exchange of blows Summerson described was transacted in the register of style, the advocates of gothic revival challenging those of neoclassicism, and then the revivalists quarreling among themselves over the minute particularities of historicist form and decoration. Yet it is important to see also that style has been linked, in his examination of Butterfield, to temporality—as Summerson challenges his reader to think of actually living in the earlier period—and that what appear as contestations of style are also a perceived incommensurability of temporal change, of one historical period succeeding another.

Of course, Summerson had his own historical context, writing about Butterfield in London in 1945, having spent the late years of the war surveying monuments and bomb damage and assembling lists for the preservation and restoration of architectural heritage that would be an important step in the century-long development of contemporary ideas and practices of preservation. (Figure 29) Summerson had already contributed to the deeper historical understanding of the architecture of the Georgian period and with his thoughts on Butterfield was beginning to do the same, with equal sympathy, for the architecture of the Victorian period.7 The question he posed about Butterfield had much less to do with the advocacy of style than with the question of temporal distance, and the question of architecture’s role in expanding or compressing that distance. As he surveyed the reality of London, his surroundings the contingent ugliness of ruined buildings, bombed churches, and vacant lots of rubble, the deliberate ugliness of Butterfield, in the challenge of deciphering its ugliness, possessed a potential to bring to light the particularities of change—stylistic change but also changing judgment.

Figure 29. Rubble and bomb-damaged buildings in the City of London, seen through the doorway of St. Stephen Walbrook.

In looking at Summerson examining a nineteenth-century architect’s likely view of Georgian predecessors, a reader enters into a similar position of historical distancing. But does ugliness still possess the same capacity—the capacity to repel a dull Mr. Smirke or to attract an intense Mr. Butterfield or to enlighten a thoughtful Mr. Summerson—within the resulting architectural temporality? Without taking recourse to philosophical assertions of a will-to-art, or a spirit of the age, one might still acknowledge that any historical period appears as a constellation of characteristics, materials, and valuations that correspond with one another. This correspondence, when examined as a historical object viewed in the register of aesthetic judgment, appears as a consistency; a consistency that certainly may belie fracture and difference in the social or economic configurations that accompany it, but a consistency nevertheless. The question posed by such consistencies is twofold: first, whether they arise only as a matter of perspective, from employing the register of aesthetic judgment as the initial framework of analysis; and second, how such consistencies shape the intersection or coincidence of historical moments that lie at a remove from one another. When a single architectural circumstance bridges different historical contexts, when its possible starting points offer little outward resemblance, then, accustomed as we are to seeing the stylistic traits that make their respective appearances consistent in themselves and therefore utterly unalike, style becomes an uncertain analytical instrument, especially when the judgment of ugliness is involved.

The Case of St. Stephen Walbrook

The city of London, spread as it is across centuries of historical change still evident as fragments within its contemporary material presence, contains innumerable such circumstances. In order to trace one such episode of stylistic commensuration, in the church of St. Stephen Walbrook, one can begin in the twentieth century, in the 1960s, as London emerged from postwar reconstruction, or three hundred years earlier, in the seventeenth-century London that rose after the Great Fire. The London of Carnaby Street and the Beatles, or the London of St. Paul’s Cathedral and King Charles II. Both were moments of rebuilding and reinvention: the earlier following not just the physical ruin of the Great Fire, but the catalyst and catharsis of the Civil War, regicide, and the Restoration of the monarchy; the later moment preceded by the total destruction of the Second World War, with the relief of victory accompanied by physical ruin soon followed by the erosion of social certainties. The events that compose the present story of St. Stephen Walbrook insist upon the coincidence of these two historical beginnings, their coexistence as historical sensibilities and their coexistence in physical forms. St. Stephen Walbrook, a small parish church in London, was one of the ancient City churches quickly rebuilt after the Great Fire, and, both then and now, enclosed by dense surroundings. Then, these surroundings were small houses, masonry to abide by the regulations of the Assize, residences and places of commerce; now these surroundings include the Rothschild Bank building by OMA, Bloomberg Place by Norman (now Lord) Foster, and other commercial structures constructed after the war. The church remains in place, a remnant and a persistence.

Sir Christopher Wren designed St. Stephen Walbrook; its central furnishing, the altar, was sculpted by Henry Moore. (Figure 30) The foundation stone of the building was laid in 1672; the stone altar was carved three hundred years later, 1972. It was the difference between the church and altar that was at issue in an intricate debate about the altar and the church that commenced in the 1960s and culminated in the 1980s. Familiar and simplistic terms of contrast were put forward—neoclassical and modern, personified by Wren and Moore, or architecture and art, or refined and primitive, or even beauty and ugliness—and polarities such as these and the problematic demarcations they suggest became instrumental terms, with their instrumentality dependent upon the attachment of aesthetic judgment to other registers. The architectural events at the church were subsumed within a broader, encompassing postmodernity, with its presumed distancing or decoupling of aesthetic production and aesthetic materials from their prior cultural groundings, so that the processes of attachment become critical events in themselves, actions of displacement of aesthetic modes of judgment into parallel registers—in this instance, into legal and theological judgments. How do such displacements of the aesthetic negotiate the consistencies of the coincident historical moments in which they occur, and how are such displacements signaled, even enabled, by judgments of ugliness?

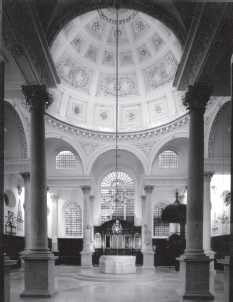

Figure 30. The interior of Christopher Wren’s St. Stephen Walbrook, viewed from the nave, with the altar sculpted by Henry Moore at the center of the crossing below the dome.

Christopher Wren’s design for St. Stephen Walbrook accorded with the prevailing liturgical practices of the Anglican church of the 1670s and accorded also with the social conventions of the parishioners who attended it. It was an auditory church, meaning a single contiguous space in which the liturgy and the sermonizing of the reverend would be audible to all the congregation. The size and arrangement of the auditory, in Wren’s view, must allow “all to hear the Service, and both to hear distinctly, and see the Preacher.”8 The proportion might vary, he allowed, “but to build more room, than that every person may conveniently hear and see, is to create Noise and Confusion.”9 With acoustic dissonance and visual disruption architecturally minimized, the focus of religious attention could be directed toward the pulpit from which the sermon would be delivered, and which was raised well above the parishioners seated in the rows of box pews. (Figure 31) Box pews, a typical furnishing of Anglican churches in that period, were individual compartments with seats enclosed by tall paneling that made parishioners all but invisible to one another while still permitting a view of the pulpit. Less visible from the pews, and also less present in liturgical terms, was the altar, set within a shallow reveal at the far end that signified the chancel. A rival focus of parishioner’s attention would have been the dome, the first such dome to be constructed in London and a precursor for Wren’s later accomplishment at St. Paul’s. This dome expanded the space that was kept compact in plan in order to satisfy the auditory requirement, and though relatively light in weight, it still required a significant structural support that would not obstruct views or hearing. Wren’s solution was to set triads of columns beneath pendentives to bring the circumference of the dome into concordance with a cruciform arrangement in the lower part of the church to produce a unified arrangement of parts. (Figure 32) These aesthetic solutions were inseparable from their social intention and consequence, with the unified arrangement the aesthetic corollary of the social effect of communal congregation.

Figure 31. An early nineteenth-century view of the interior of St. Stephen Walbrook shows the congregation seated in box pews, and the reverend sermonizing from the pulpit. Illustration by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin for The Microcosm of London (London: Rudolph Ackermann, 1808–10).

Figure 32. The interior of St. Stephen Walbrook in 1957 with chairs arranged to face the altar in the chancel. At the center of the image can be seen Wren’s skillful solution for the transition from dome to the cruciform arrangement of columns.

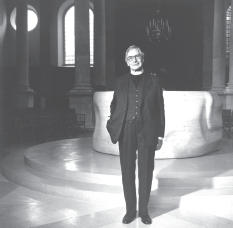

Figure 33. Lucinda Douglas-Menzies, Edward Chad Varah (1988). Bromide print.

By 1967, three centuries further along and the year in which the idea of the new stone altar was conceived, the liturgical practices of the Anglican church had changed in significant ways. Communion was held much more frequently— weekly rather than three or four times a year as in Wren’s day—which reinforced the communal, congregational basis of the Anglican church. The proximity of parishioners and reverend was thus emphasized, and no longer just visual or auditory, but now an intimate spatial and emotional proximity as well. In many Anglican churches, the altar was moved out of the chancel, closer to the center of the congregational body. Box pews, which had often been owned or rented by individual families, had been replaced in the nineteenth century with seats or benches. Such changes paralleled social transformations; the slow erosion of class privilege, for example, contributed to the removal of box pews. And of course London in the late twentieth century was a very different social environment, one with which the rector of St. Stephen Walbrook, the Reverend Chad Varah, was quite extensively engaged. Varah was, famously, the founder of Samaritans, the first suicide prevention helpline; he was an outspoken and unembarrassed advocate of sex education, and moonlighted as an author of science-fiction comics. (Figure 33)

Varah’s efforts toward social engagement were not unrelated to the initiative he undertook at St. Stephen Walbrook, where, with a campaign already under way to repair structural damage, consideration was being given to new arrangements for the interior. In 1967, Varah and one of his churchwardens (a lay member responsible for church administration) approached Henry Moore with the commission for a new altar. The sculptor had been suggested by the churchwarden, Peter (now Lord) Palumbo, a property developer who was himself a patron of contemporary art and architecture. (He would purchase Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in 1968, and later bought Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kentuck Knob in Pennsylvania.) The rector provided the idea of the commission itself, for an altar to be placed at the center of the crossing, under the dome; an altar “in the round, with the priest moving around the perimeter.”10

Figure 34. Henry Moore sculpted the altar into a cylindrical form, with its top surface a flat tabular plane but its sides irregularly contoured by hollows and ridges of different shapes and depths.

Varah introduced the commission to Moore not by way of liturgical details, but rather, it seems, though evocations of its spiritual dimension: “I begged him [Moore] to forget any altars he had seen, if he had in fact seen any, and to think of something going back to the dawn of history, something primitive and inseparable for [sic] man’s search for a meeting place with his God.”11 The altar could, he said, be the “quintessential, archetypal, rough hewn altar of the Old Testament.”12 For his part, Moore had of course seen altars, but this was only his second commission for a religious work. (He had sculpted a Madonna and Child for a parish church in a provincial town during the war, but none since; his Mother and Child for St. Paul’s Cathedral would follow in 1983.) Moore approached the Walbrook commission by visiting the church to sit contemplatively in its interior, sometimes for hours, to study the procession of light across Wren’s space. Apparently given leave to determine the dimensions, Moore decided that the round altar should not overlap the fifteen-foot spacing of the transept columns, but also that an initially proposed five-foot diameter was insufficient; something bigger was needed “to produce a massive effect.”13 The height of the altar serves its purpose, allowing the priest to use the top for communion, but it also draws the surface up toward the plane implied by the column bases. These bases themselves seem oddly tall to a visitor now, but their height was originally set to align with the top of the box pews. Drawings of the new altar were finished and a full-scale model placed in the crossing early in 1972, and the final piece arrived at Moore’s studio from the stoneworks early in 1973. (Figure 34) The completed altar was a cylinder of travertine, eight feet in diameter, three-and-a-half feet high, ten tons of weight to rest upon a broad footpace; smooth in its surfaces, level on its top but with subtle undulations carved into its sides that create a constantly changing articulation of depth within the circumference of the drum.

It was not until the early 1980s that the restoration work on the foundations and floor progressed to a point where the altar could be installed in the church. But this installation still required what is called a faculty, a permission granted by diocesan authorities for any significant alteration to the fabric or furnishings of an Anglican church, and with this requirement, Moore’s altar and Wren’s church, with their respective aesthetic predispositions, were drawn into a social institution of law. A faculty consists of a judicial process in which the advocates of the alteration—typically the incumbent priest and the churchwardens—petition the Consistory Court, an ecclesiastical court that supervises church administration for the bishop of that diocese. A single judge, called a chancellor, presides over the Consistory Court and hears the case in the familiar forms of common law jurisprudence: one brief in support of the faculty presented to the court by a barrister and a countering brief in opposition.14 The chancellor hears testimony from witnesses who may be examined and cross-examined, and detailed evidence may be submitted. The chancellor considers the arguments in light of other cases that may have established relevant legal precedents, and then either grants or refuses the faculty.

The Consistory Court of the Diocese of London heard the case of St. Stephen Walbrook beginning in January 1986. The case was an important one. The church had been closed for years by the reconstruction and the altar would be key to resuming its pastoral role. Yet because the building had been listed Grade I for preservation in 1950, such a significant change compelled careful deliberation. In the Consistory Court hearing, the chancellor pursued two distinct lines of interrogation, one aesthetic and the other theological. The first, the aesthetic, questioned the manner in which Moore’s altar would affect Wren’s architecture. Would the massive stone altar enhance or degrade the perceived perfection of the architecture? Were the two works of “totally different idiom” compatible, or were they insuperably at odds?15 Certainly the testimony was at odds, as the chancellor noted and as exemplified in a comparison of two statements, one for the petition and one against. Mr. Peter Palumbo, the churchwarden: “As a general proposition, any two works of art, each of the highest excellence, can live together and each will set off and advantage the other.” Mr. Ashley Barker, surveyor of historic buildings: “To take a work of great geometrical precision and introduce into it something large in comparison with the original building and of a different artistic nature is venturing on the impossible.”16

Possibility and impossibility here mark out the boundaries of a judgment, potentially a judgment of ugliness, arising from the contrast of two objects that are to be placed in juxtaposition. The difficulty is clear enough: in Moore’s sculpture one encounters a tactility, an emphatic materiality, a density of mass, but an indeterminacy of form and a “subtlety of line.”17 Wren’s architecture by contrast proffers an elision of mass, and a precision of line and form; the historian Kerry Downes saw in Wren’s drawings of the church in sectional view: “Wren at the most severely geometrical, even theoretical, stage of his thought in which no more is committed to paper than the plane projection of the edges between surfaces and spaces.”18 Moore’s sculpture also is severe, but not as abstraction, rather as what the Reverend Varah called “something primitive.” This is not to say that either is simple. (Figure 35) The conjunction of dome and crossing comprises the ring and the twelve columns, and between them the eight equal arches that cleverly mask the differentiated barrel and groin vaults of transept and chancel, and the varied windows eroding the solidity of the exterior wall. And perhaps the volumetric complexities of this transitional space are echoed by the concavities and convexities of the altar, as its circular mass certainly echoes the circular void of the dome.

Figure 35. The volumetric complexity of Wren’s arrangement of the structural transition at the base of the dome seen in relation to the sculptural volume of Moore’s altar below.

In the setting of the Consistory Court, through the testimonies of witnesses, a viewing of the altar, a study of the church, substantive disciplinary conventions and concepts such as style and intention could be introduced into the space of law, but once there they did not simplify the task of judgment. The chancellor and the barrister in opposition agreed that an altar could be neither a convenient boulder nor a recumbent nude with settings upon it, but this did not resolve the nature of the object in question, which was not a boulder and not a statue. Endeavoring to understand the significance of the massive stone, the chancellor asked Varah how an altar of this shape might differ from one found at Stonehenge, to which the reverend replied that Stonehenge pointed toward a gruesome past and the new altar toward a redemptive future.19 As the chancellor noted, “A great deal of evidence was given by distinguished experts as to the beauties of the church and as to the beauty of the piece of sculpture. I accept without reservation that both are beautiful and I need not further discuss that part of the evidence. But are the two things congruent?”20 The chancellor’s question was nowhere near as simple as it might have sounded, for congruity is the aesthetic horizon of several different manifestations. Congruity appears as concordance, the stylistic concordance of forms; but also as consistency, the perceived consistency within subjective experience; and it is recognized also as integrity, the perpetuated integrity of an artistic intention.

To ask if these two things were congruent, or if their adjacency would render their respective beauty as a condition of ugliness, was to pose a question of aesthetic judgment, but a complex one that could not be indifferent to corollary social implications. Wren’s design contrived a conflation of longitudinal and centralized arrangements: the longitudinal emphasis produced by the line of columns flanking the nave and framing the chancel; the centralized effect produced by the frame of columns surrounding the crossing. The columns are at once axial and a quartet of corners. (Figure 36) Witnesses opposed to the faculty argued that introducing the massive Moore altar directly under the dome would unacceptably change the church interior, doing “drastic violence” by disrupting or even destroying the architectural geometry.21 It would, they insisted, enforce the centralized reading of the plan and repress its longitudinal expression. Ashley Barker, opposed to the faculty: “ ‘The presence of the great solid form of the proposed altar under the domed centre would be to create an expectation of symmetry all about it by blocking the longitudinal and cross axes and establishing a false centre—reflecting each incident axis in turn—which, in my contention cannot have been the architect’s intention.’ ”22 Reverend Peter Delaney, in favor of the faculty: “ ‘The placing of the circular altar directly under the dome will strengthen the feeling of space and engage those who visit and worship around it in Wren’s original intention of a community under the dome.’ ”23

These confident yet contradictory assertions about the architect’s intention reveal a conflation of planes of judgment presented to the court, with architectural arrangement joined to theological consequence. The aesthetic consequence of the new altar could not be contained within aesthetic judgment. In 1971, Palumbo, as churchwarden, had written to Moore to ask whether, “since the Church and its new altar will be complementary … you have any preferences for the colour scheme inside the church, i.e. stone colour, white, off-white, etc.”24 Even if (as Ashley Barker reminded the court) “for Wren, the natural beauty of architecture was from geometry,” the perception of this natural cause of beauty brought the workings of aesthetic judgment into relation with judgments of purpose, the wholeness of the church as architecture in relation to the wholeness of the church as congregation.25 The chancellor certainly was not convinced that Henry Moore’s sculpture would complement Wren’s church, and he was prepared to refuse the petition for the faculty for the stone altar on that grounds. As the barrister in opposition reminded the court, it was within his discretion to do so if the proposed altar were offensive or unsuitable. The testimony and the cross-examinations had made clear that the chancellor agreed with opponents that the juxtaposition of altar and church was incongruous, indeed that it was, even if decorum prevented the use of the word, a condition of ugliness. But the chancellor concluded that the decision of the case could not be settled upon the discriminations of aesthetic judgment only, explaining that a crucial doctrinal question preceded the aesthetic concern and that it was a judgment on doctrine that prompted him to refuse the faculty. What was this decisive doctrinal consideration? It was that Moore’s sculpture was indeed an altar, and was therefore certainly not a table.

Figure 36. The overlapping configurations of the centralized and longitudinal arrangements can be discerned in this 1793 plan. The entrance to the church is at the right in the drawing. The shallow nave is defined by just two pairs of columns, and the space under the dome is framed by twelve columns arranged in a square. To the left is the shallow chancel where the original altar was located. Alexander Poole Moore, Plan of St Stephen Walbrook (1793).

This claim transfers the architectural assessment into an interpretation about theological significance. In the Anglican church, the Eucharist, the rite of communion during Mass in which wine and the wafer of bread are consumed as an enactment of a congregant’s communion with Christ, is celebrated in front of an object that is understood as a table and not an altar. Church doctrine may now use the two words interchangeably, but theological understanding distinguishes between them. The chancellor explained it this way:

The distinction between “altar” and “table,” when the words are correctly used, is in itself essential and deeply founded, since “altar” signifies a place where a sacrifice is to be made, a repetition at every Mass of the sacrifice of our Lord at Calvary. This was the view of the Mass as held in the unreformed Church in England immediately before the Reformation, whatever may have been the case in the earliest ages of the Church. The reformers took the other view, viz that the Holy Communion was not a renewed sacrifice of our Lord, but a feast to be celebrated at the Lord’s table. The latter view prevailed, at least from the Prayer Book of 1552, with the result that “altars” were removed from churches and “tables” substituted.26

The chancellor ruled that “the marble sculpture [is] not, within any ordinary definition, a table” and that the petition must therefore be refused on the point of canon law.27 For this ruling, he depended upon a prior sequence of cases heard within the ecclesiastical courts extending back into the early nineteenth century, transferring what had been an aesthetic incongruity, and a judgment about ugliness, into a matter of legal classification and definition.

Temporality and Materiality

The debate over the altar in St. Stephen Walbrook was a debate over aesthetic propriety in the context of perceptions of historical continuities and change expressed through style. Was it proper to introduce this massive stone, primitive, emotionally resonant, into the precise, rational articulations of columns, dome, and surfaces? Would the sum be an increased perfection or a despoiled one? Would the result be a condition of beauty or ugliness? These questions were being posed in London in 1986, at that moment when the kindling of postmodern architecture, political conservatism, patronage, and economic neoliberalism had ignited into front-page controversies. Not far from St. Stephen Walbrook, the new Lloyd’s of London building, designed by the Richard Rogers Partnership, had just opened. East of the City, construction was about to begin on the massive Canary Wharf development, while elsewhere in London the Tate’s Clore Gallery, designed by James Stirling, and the TV-am building by Terry Farrell and Partners, testified to the unsettled, uncertain state of architectural style. In this context, the debate over the stone altar at St. Stephen Walbrook was a proxy for a larger debate over the confrontation of high modernism and a rising historicism, and the terms of that larger debate had their cognate terms in the ecclesiastical proceedings. For one, the fundamental consideration of whether newness or change represented advance or degradation paralleled the theological question, so crucial in nineteenth-century Britain, of development and perfection, with the former the possibility of mankind’s progress toward better states of existence and the latter the conviction that the better state of mankind was prior rather than future.28 In addition, in a parallel of ecclesiastical adoption of aesthetic concerns, the role of language, the legibility of symbolic form, and the political function of architecture were each among postmodernism’s critical points of inflection.29

By examining not only their conventional manifestations, but also their appearance in the longer duration and different conjunction of postmodernity that was the case of St. Stephen Walbrook, it may be possible to shift focus from the overt characteristic of style to a question underlying postmodernism: how are appearances of architectural congruity to be understood in the contexts of postmodernity, in which the aesthetic register has been loosened and detached from the supports of its former social and political structures? This circumstance prompts the assessment of not only the congruity within or between architectural objects, but the congruity between historical periods of differentiated stylistic appearance; crucially, it prompts also the assessment of congruity—and incongruity—between separate registers or spheres of judgment, for it is in this distance that ugliness assumes its possible instrumentality, not within the aesthetic but outside of it.

The dispute over the altar in St. Stephen Walbrook proceeded not forward but backward, to the early nineteenth century and another ecclesiastical court case that the chancellor’s judgment used as a binding precedent. In 1839, an energetic group of Cambridge University undergraduates founded the Cambridge Camden Society, later known as the Ecclesiological Society, an organization dedicated to what might be colloquially described as the study of churches and liturgical arrangements.30 (William Butterfield would become one of the group’s most accomplished and determined architects.)31 They were deeply influenced by the Oxford Movement, a group of Anglican leaders who were pressing for the return to what were called “high church” practices, or ritualism. Ritualism carried fraught political connotations because it was understood to veer closely toward the beliefs and liturgical principles maintained by the Roman Catholic Church. For centuries after Henry VIII split from the Roman Catholic Church in the sixteenth century, adopting the tenets of protestant reform to establish the Anglican church, Roman Catholicism met with suspicion and hostility in Britain. Only in 1829 did legislation provide for the “emancipation” of Roman Catholic practice, and even then much antipathy persisted to what was freely denigrated as “Popery.” So those who endorsed seemingly Catholic tendencies, such as the return of medieval liturgical practices or the restoration of an atmosphere of mysterious ritual and rich architectural decoration, could encounter vehement denunciations.

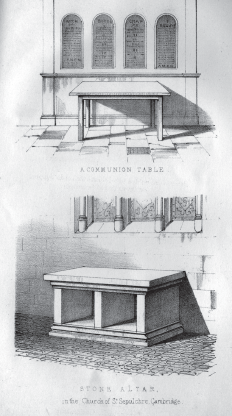

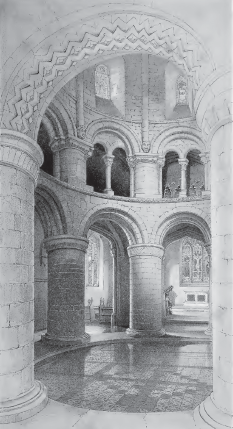

For the Cambridge Camden Society such concerns came to a crisis in 1845, with the society’s involvement in the restoration of the Round Church (St. Sepulchre) in Cambridge. In only a few years since its founding, the society had established itself as the leading authority on church buildings and so offered its expertise (and financial support) for the restoration of this dilapidated twelfth-century church. Members of the society served as the committee to oversee all aspects of the restoration, an arrangement that proceeded happily until the incumbent of the parish, Reverend Faulkner, discovered that the existing wooden communion table had been replaced with a new stone table that could too readily be described as an altar. Accompanied by fierce polemics—for example a sermon titled “The Restoration of Churches Is the Restoration of Popery”—the issue of the stone altar quickly entered the ecclesiastical courts.32 After the Consistory Court granted a faculty for the altar to remain, Reverend Faulkner appealed that decision to the Arches Court, the next higher ecclesiastical court, which represents the archbishop and is presided over by a judge called the Dean of Arches. The dean elaborated three points of inquiry: whether the object in question was to be considered a table or an altar; whether the use of stone for this object was permissible; and whether this object was moveable or set permanently in place. In other words, three registers of analysis, the symbolic, the material, and the functional, with the latter two categories—the materiality and the mobility of the table—inseparably linked to the first, its symbolic form.

To arrive at his decision, the dean proceeded through a comprehensive historical accounting of Church of England canon law regarding communion tables. Before the sixteenth-century Reformation, he reported, Roman Catholic liturgical practice employed an altar, fixed in place on the eastern chancel wall and carved in stone in resemblance of a tomb. During the ritual of communion, the priest would stand facing the altar with his back to the pews. According to reformers, this position could only reinforce a superstitious veneration of the Eucharist as a sacrificial rite in which the bread and wine of communion are transformed in substance into the blood and body of Christ. The reformed Church of England repudiated the doctrine of transubstantiation and its sacrificial emphasis, regarding communion instead as a congregational feast, a celebratory rite in the image of the Last Supper. In order to forestall a congregation’s adherence to superstitious belief the reformers called for the altar to be replaced with a table, a table moreover that could be moved out from the chancel into the body of the church, so that the laity would be able to see and understand all the actions of the priest. (Figure 37) Within the mysteries of communion, the aestheticizations of style were to be superseded by a realism of facticity. The change, the dean reasoned, revealed that “something more than the mere alteration of name was intended. It would not have satisfied the purpose for which the alteration was made merely to change the name of altar into table. The old superstitions would have adhered to the minds of the simple people, and would have continued so long as they saw the altar, on which they had been used to consider a real sacrifice was offered. For these reasons I consider a substantial alteration of the structure was made.”33

Figure 37. Comparison of a holy table made of wood, above, with the stone altar installed in the Round Church, below. In the words of Archdeacon Thomas Thorp, the chairman of the Restoration Committee, “a specimen of the kind of Altar commonly found in new churches” compared to “the unpretending Altar, now ejected from the Round Church by the Judgment of the Court of Arches.”

Continuing through his scrupulous historical analysis, the dean determined that the holy table might be either wood or stone (though wood being more common and more suitable), but that irrespective of material the table must not be fixed in place. One of the “superstitious notions that belonged to the Popish mass … was that it was essential that the altar be immoveable.”34 And so the holy table, in necessary contrast, must be moveable.35 Its materiality and mobility settled, the symbolic dimension remained: if the change from altar to table held more significance than mere change of nomenclature, then the essential nature of the “table” should be defined in some manner, such that its symbolic resonance might be correctly construed (just as an “altar” correctly construed held the symbolic charge of sacrifice). To resolve this point, the dean reasoned from symbolism to form, from the symbolism intended to the form capable of fulfilling it. Noting that early canon laws on the sacrament of communion had instructed that “ ‘the bread be such as is usual to be eaten at the table with other meats,’ ” he asked, “Can the word ‘table’ mean anything but that table at which meals are usually eaten?” The holy table, therefore, should be “nothing more than an ordinary and decent table.”36 The legible correspondence of language and form completed the framework for his judgment upon the stone altar proposed for the Round Church: “What is the notion that would present itself to any one’s mind of the word ‘table,’ taken abstractedly. Surely it would not be that of the object now under consideration—a stone structure of amazing weight and dimensions immovably fixed. It is undoubtedly possible, by an ingenious argument, to contend that the present erection is a ‘table’; it may be so according to one definition given by Dr. Johnson—‘a flat surface raised above the ground’; but that notion would not readily present itself to the mind; such is not the ordinary meaning of this word.”37

Figure 38. Drawing of the interior of the Round Church immediately after its restoration by the Cambridge Camden Society, with the stone altar visible through the arch at right.

The dean’s ruling could not have been in doubt at this point, but one final contention remained to be addressed. The petitioners argued that they had undertaken the renovation with the aim of restoring the “original architectural character” of the Round Church, that is, restoring its Romanesque interior, physically and atmospherically. (Figure 38) With this goal, the petitioners testified, “it became essential, in accordance with such restoration and to preserve the uniformity of the internal arrangements of the said church, that a new communion table, corresponding with such arrangement, should be provided.”38 Reverend Faulkner submitted his rebuttal to this claim: “if the said stone altar … [is] intended to be in accordance with the ancient design of the fabric of the said church and in uniformity with the original internal arrangements thereof, … they are of necessity … such as were and are erected and used in Popish churches, inasmuch as the said church was originally designed and built in Popish times and used for Popish purposes.”39 The dean concurred with the objection (though he was careful to indicate that he did not attribute heretical motives to the petitioners). He stated unequivocally that the restoration of the physical church to a uniform state could not be taken as a compelling justification for the unorthodox altar: “The Court can never hold that the uniformity of a building, the architectural style of a building, is to be consulted and to be preferred to that which it is the intention of the Act of Parliament to preserve—uniformity in divine service. It cannot sacrifice that great principle to the minor one of the uniformity of the architecture of the church.”40

Here then was a crucial claim to be carried forward from the nineteenth-century legal arguments into the twentieth-century debate on St. Stephen Walbrook. The uniformity—that is to say, the consistency or the unity—of a church’s architectural style could not be given preference over the uniformity of liturgical practice—the consistency of rituals performed within different Anglican churches. Liturgical consistency had been defined by the parliamentary Acts of Uniformity, legal measures designed to constrain interpretation, idiosyncrasy, and, above all, unorthodoxy. Of course, no similarly binding legal measure pertained to architectural form and decoration, but in returning to the case of St. Stephen Walbrook, the phrase if not the instrument—acts of uniformity—might be appropriated in order to propose the idea that congruity should be understood not as an inherent quality, but as a condition that is produced, that is forged by the encompassing framework of an act of uniformity. In other words, the incongruity perceived by opponents to be the certain result of the introduction of the Moore altar into Wren’s architecture arose from the framework of judgment within which these objects were set, and this framework of judgment might set the terms of uniformity to be applied to both aesthetic and theological objects. The judgment of ugliness in this case would not be a judgment of appearances—incongruity as a discomfort, an unsuitedness, a contradiction—but a judgment of consequences—incongruity as impropriety or ineffectiveness.

Language, Ambiguity, and Ugliness

In early 1986, the chancellor of the Consistory Court had refused to grant a faculty to admit the altar designed by Henry Moore into the church designed by Christopher Wren, having judged that the incongruence between the two was so certain that the installation of the altar would spoil the spatial perfection of the church, and that the altar could not in any event be permitted because it did not meet the canonical requirements for a holy table. The rector Chad Varah and his churchwarden chose to appeal this decision. Normally the appeal would be heard by the next higher ecclesiastical court, the Arches Court, but in this instance, because the chancellor determined that the case turned on a point of doctrinal interpretation, the appeal was heard directly at the highest juridical level, in the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved (CECR). Created in 1963, the CECR assumed what was the former prerogative of the Privy Council to settle doctrinal disputes.41 Though in existence for nearly twenty-five years, the court had convened only once before, so rare were the issues it addressed.

In reviewing the St. Stephen Walbrook appeal, the five judges of the CECR made clear the unencumbered juridical position of their court. According to its founding legislation—which might itself be understood as a marker of postmodernity—the CECR was not bound by the precedent of any prior decisions of the Privy Council: “This court is therefore free to consider the issues afresh, taking account of more recent legislation and historical and theoretical knowledge which was not available to the courts in the mid-nineteenth century.”42 Nor was the court bound by declarations of the Arches Court, an important distinction because that lower court had set a number of judgments regarding alterations to listed churches, protected, like St. Stephen Walbrook, by civil preservation statutes. The Anglican church had long held statutory exemptions that recognized the priority of theological function over preservation, but over time the Arches Court had built a standard of judgment that emphasized the proof of theological necessity to justify changes to listed churches.43 Not bound by precedents in the Arches Court, the CECR did not adopt its standard.

Reviewing the chancellor’s decision, the judges concluded that because the expert witnesses for both sides had presented judgments of an aesthetic rather than technical nature, the “opinion of either [side] on the issue of congruity could [not] be shown to be right or wrong in any relevant sense.”44 Nevertheless, they were surprised the Chancellor had given such slight regard to some testimony, that of Kerry Downes in particular, given his scholarly authority on Wren. They themselves highlighted and quoted Downes’s careful definition of “ambiguity” as an aspect of architectural experience: “By ‘ambiguity’ [the witness] meant—‘the possibility or even the inevitability of a particular group of components being readable in more than one way with differing sense.’ ”45 Though this appreciation of ambiguity is unremarkable as a point of architectural historical emphasis—especially in 1986—an ecclesiastical court might be expected to have found ambiguity to be less than desirable, at least to the extent that it muddled an underlying theological uniformity. What this moment of judicial elucidation then reveals, perhaps, is that to recognize the appearance of ambiguity was also to discern the tenuousness of architectural or theological congruity, and that the court’s inquiry into ambiguity signals its effort to formulate an understanding of congruity adequate to and effective within the dislocations, the ungroundedness, of postmodernism. To wrestle with the possible judgments of ugliness was precisely to occupy this uncertainty in the effort to discern what purchase an aesthetic quality or an aesthetic judgment might have upon the social dimensions of theological thought and practice in the late twentieth century.

The crucial question remained, whether or not the stone altar could be accepted as a holy table within the canons of the Church of England. The chancellor had decided that it could not, using the case of the Round Church as a forceful precedent. He acknowledged that twentieth-century canon law revisions had clarified that a holy table could be made of stone, and could also be immoveable, but he still regarded the “reasoning” of the 1845 ruling to be “binding,” and therefore that the essential factor was the “table-ness” of the object: “the holy table in the church must still be a table.”46 “What is the connotation of the word ‘table’?” the chancellor had asked, answering that “it must be construed in its ordinary sense,” endorsing the definition provided by the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary and setting as his test the likelihood that any observer would look at the altar and recognize it as a table. Regarding Moore’s sculpture, he found that “it seems difficult to suppose that an ordinary educated speaker of the English language would say, ‘That is a fine table’ or even ‘That is a table.’ On this ground I am of the opinion that this petition must fail, not as a matter of discretion, but of law.”47

The CECR judges had little patience for his seeming certainty. As one judge put it, “I did not find it easy to follow the philosophical argument concerning the concept of ‘tableness.’ I find myself in sympathy with Dr Johnson’s definition of a table as ‘A horizontal surface raised above the ground, used for meals and other purposes,’ and I prefer this to the definition in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on which the chancellor relied. . . . I have no doubt that the Henry Moore altar falls within the wide bounds of what can be reasonably called a holy table.”48 Apparently suspicious of the claim of the transparency of language, this judge was endorsing instead a compensatory breadth of definition. On these grounds, the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved reversed the chancellor’s decision and granted the faculty for the stone table to be installed in St. Stephen Walbrook.

A visitor to Wren’s church today will climb the stairs, pass through the vestibule, and find Moore’s altar standing immovably below the dome. (Figure 39) With its strongly contoured sides a semblance of erosion, and with the surrounding architectural elements forming a rigid geometric frame, the altar conveys an echo of Wood’s measured drawings of the standing stones at Stonehenge. (see Figures 3–5) It is easy to imagine a drawing for St. Stephen Walbrook similar to those from Wood’s survey, with an irregular form set within the precise lines of a ruled boundary. Neither drawing represents an ugly object, not in any absolute sense, but each captures a possibility for a judgment of ugliness. The participants in the altar debate at St. Stephen Walbrook did not make explicit reference to ugliness, nor did their ecclesiastical predecessors, but as Summerson’s interpretation of Butterfield suggested (in agreement with the propositions David Hume put forward two centuries before) ugliness may be the situation that encompasses an object more than a quality of the object itself.49 Occurring when it did, in 1986, the debate over St. Stephen Walbrook participated, unobtrusively perhaps, but participated nevertheless, in discursive challenges being staked in the confrontation of late modernism and a newly championed historicist postmodernism. To argue about ambiguity, to argue about symbolic form and legibility of meaning, to argue about precedents and about language and its transparency—surely this was to argue in the very terms being deployed in surrounding debates about postmodernist architecture in London and elsewhere in Britain.

Figure 39. The stone altar installed at St. Stephen Walbrook at the center of the circular arrangement of pews. The artist Patrick Heron designed the kneeling cushion for the footpace in 1993, after the faculty for the altar had been granted.

Yet in the case of St. Stephen Walbrook, these arguments took place not on the pages of architectural journalism but in the space of the law, a distinctive space of judgment in which the terms of architectural thought assumed different valences, different associations, different temporalities. The space of law, and in this instance the more particular space of ecclesiastical law, stands aside (though not in isolation) from the currents of adjacent social or political endeavors. The fact of jurisdiction marks this apartness and affirms the application of privileged frameworks of interpretation and procedure; the adversarial process emphasizes conflicting evaluations of meaning and consequence, while the delegated sovereignty of the judge locates and constructs the authority of decision; and the requisite regard for precedents, as in common law generally, persistently collapses prior and present historical moments. Rather than isolating the independently motivated development of architectural practices and theological practices, ecclesiastical law sets the interactions, the frictions, between architecture and theology as the actual object of inquiry.

In the case of St. Stephen Walbrook, this friction appeared as the concern for ambiguity, a concern that did not suggest a blurring of boundaries so much as the coexistence of multiple well-delineated boundaries of congruity. If Wren’s architecture is the object circumscribed by a boundary, then ambiguity manifests in the congruities within his complex design; if Moore’s sculpture is the bounded object, ambiguity manifests in the congruence of the stone and sacramental ritual. But when Wren’s architecture and Moore’s sculpture are considered together within a boundary of judgment, then ambiguity has a different significance, and congruity also, because not only their present appearance but their past and future significance must be accounted for within the boundary. The case of St. Stephen Walbrook evidences that the production of such a boundary, or horizon of congruity, is the essential task undertaken by acts of uniformity, whether they are institutional and legislative, or contingent and aesthetic, or as we have seen here some amalgam of the two. It is such acts of uniformity and their attempted juridical reconciliations that give deeper substance to the visible incongruities of postmodernism, and it was a judgment of ugliness that prompted the need for such reconciliations to be attempted.

At what point does the huge stone at the center of the church become ugly, or become a prompt for a judgment of ugliness? In its raw state, when it has not yet been presented as an object of aesthetic regard; or when sculpted into cylindrical shape with irregular hollows along its sides, when it may be judged for form, color, effect, and presence; or when it is given the designation of altar and placed into an architectural setting? The question can be addressed to the previous examples as well, to the stone cut from the quarry and set into the fabric of a building to be decayed by the atmosphere that encompasses it, and to the concrete given coarse textures and board markings, arranged into irregular forms and left in its unadulterated grayness. In none of these is ugliness an inherent quality, essential to the object. In each, ugliness is a category of assessment, manifest in different terms such as nuisance, irritation, or incongruity, for which stone is the prompt rather than the conclusion. The judgments arise initially as aesthetic judgments, but are in each case also social, collective rather than individual, and catalyze the constitution of some aspect of communal civic life. From the controversies precipitated by architecture—and therefore from aesthetic beginnings, or with aesthetic influence—and from the judgments that follow emerge social instruments that participate in the maintenance of the city, the definition and redefinition of norms, and the regulation of change over time.