INTRODUCTION

Once upon a Time, a Toddler Was Elected President . . .

At age two, children view the world almost exclusively through their own needs and desires. Because they can’t yet understand how others might feel in the same situation, they assume that everyone thinks and feels exactly as they do. And on those occasions when they realize they’re out of line, they may not be able to control themselves.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Caring for Your Baby and Young Child

In this book I make two arguments, one simple and one not so simple. The simple argument is that Donald Trump behaves more like the Toddler in Chief than the Commander in Chief. Many of Trump’s critics have argued this, but that is not the primary source of my evidence supporting this claim. In more than a thousand instances since his inauguration, Trump’s own supporters and subordinates have made this comparison as well. The staffers who work for Trump in the White House, the cabinet and subcabinet officers who serve in his administration, the kitchen cabinet of friends and confidants who talk to him on the phone, Republican members of Congress attempting to enact his agenda, and longstanding treaty allies of the United States trying to ingratiate themselves to this President have all characterized Donald Trump as possessing the maturity of a petulant child rather than a man in his seventies.

The less simple argument is that having a President who behaves like a toddler is a more serious problem today than it would have been, say, fifty years ago. Formal and informal checks on the presidency have eroded badly in recent decades, and Trump assumed the office at the zenith of its power. For a half-century, Trump’s predecessors have expanded the powers of the presidency at the expense of countervailing institutions, including Congress and the Supreme Court. Presidents as ideologically diverse as Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama all took steps to enhance executive power. To be sure, Trump has attempted massive executive-branch power grabs as well. This is problematic, but the underlying trends—all of which predate Trump’s inauguration—make the existence of a Toddler in Chief far more worrisome now than even during the heightened tensions of the Cold War.

Consider navigating the ship of state as analogous to driving a car on a twisty mountain road. The risk of driving off the side of a mountain is real. Two things can prevent a catastrophe: the driver’s good sense and guardrails separating the road from the precipice. The guardrails were badly damaged before 2016, but a skilled driver could still navigate the road. In that year, however, the country elected the most immature candidate in American history to drive the car. The result has been a reckless President operating the executive branch like a bumper car, without any sense of peril. The car has not careened completely off the road yet, but that is due more to luck than skill. The possibility for a fatal crash remains ever-present. Even more disturbing, the driver is not getting any better at his job. He is just getting more confident that there is no risk to what he is doing.

![]()

Far too much of Donald Trump’s behavior is comparable to that of a bratty toddler. Let me be as precise as possible about what this means. I am not saying that Trump is a toddler. Multiple physicians—some of admittedly dubious provenance—have confirmed that Donald Trump is a borderline-obese white male over the age of 70. Furthermore, even casual observation reveals that this is not a Benjamin Button situation in which Trump is aging into a small child. Biologically, the 45th President of the United States is a fully grown man—just like the 43 men who preceded him.1 I am arguing that unlike his predecessors, Trump’s psychological makeup approximates that of a toddler. He is not a small child, but he sure as heck acts like one.

Furthermore, I am not indicting the behavior of toddlers by comparing Trump to them. The 45th President shares a lot of behavioral traits with small children. The difference, however, is that toddlers have a valid justification for their behavior. Many of the unsavory traits associated with toddlers reflect their effort to make sense of the world given their limited capabilities. At the toddler stage of cognitive and emotional development, children throw tantrums and act impulsively because they have no other means to cope with their environment. Over time, of course, toddlers grow out of these behaviors. Donald Trump shows no such signs of maturation. He offers the greatest example of pervasive developmental delay in American political history.

These are strong statements to make, and readers should approach such provocative claims with skepticism. This is particularly true for those Americans who voted for and continue to support the 45th President. Donald Trump is a polarizing figure in polarized times. The incentive to ridicule the President is strong among those who resist Trump’s agenda. Since Trump’s election, Democrats have frequently characterized the President as possessing the maturity of a boy who has yet to master his toilet training. Numerous party leaders have deployed this analogy. In December 2018, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer accused Trump of throwing a “temper tantrum” when a bipartisan appropriations bill contained no funding for a wall along the US-Mexico border. In January 2019, former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates tweeted that Trump was behaving “like a spoiled two year old holding his breath.” Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi blasted Trump for his obduracy during the 2018/19 government shutdown, telling reporters, “I’m the mother of five, grandmother of nine. I know a temper tantrum when I see one.”2 A few months later, Pelosi told the New York Times that Trump has a short attention span as well as a “lack of knowledge of the subjects at hand.”3 2020 Democratic candidates for President have also compared Trump to a preschooler.4

Nor is it difficult to find examples of commentators characterizing Trump as a toddler. Indeed, these analogies predated his inauguration day. In June 2016, Politico’s Jack Shafer wrote, “This is the first time we’ve seen a candidate assume the psychological and reactive profile of a small child. Trump seethed like an irritable 2-year-old instead of exhibiting the kind of restraint and comity we usually associate with a finalist in the presidential sweepstakes.”5 One textual analysis from the 2016 campaign concluded that Trump’s speeches had the emotional maturity of a toddler.6 A few weeks after his election victory, The Daily Show’s Trevor Noah made the comparison more explicit: “We’ve come to realize that there’s a good chance that President-elect Trump might have the mind of a toddler, and if you think about it, it makes sense. He loves the same things that toddlers do. They like building things. They love attention . . . always grabbing things they’re not supposed to.”7

Trump’s inauguration did not slow the use of the toddler analogy—if anything, its frequency increased. On television, commentators ranging from Don Lemon to P. J. O’Rourke have characterized the President as a two-year-old brat. Protestors and editorial cartoonists depict Trump as a giant man-baby. Within the first few months of his presidency, even conservative columnists such as David Brooks and Ross Douthat were explicitly comparing Trump to a child.8 In the fall of 2017, the Atlantic’s David Graham wrote, “How does the presidency work when the President’s aides treat him like a child? The immediate answer is, not very well.”9

By 2019 the analogy’s use had proliferated even further. The Washington Post’s Dana Milbank penned a column predicated on the idea of Trump’s immaturity as President: “Though we often hear the mantra ‘this is not normal,’ what the President is doing actually is normal. For a 2-year-old. If you want to understand this White House, turn off Wolf Blitzer and pick up Benjamin Spock.”10 The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer leaned on the analogy during the January 2019 government shutdown, going so far as to describe the new Democrat-controlled House of Representatives as a parent trying to introduce discipline into a young boy’s upbringing: “The inauguration of a new Congress means that for Trump, the days of easily getting his way are over. And like a child facing his first taste of discipline, he is chafing at the restrictions. But that’s what makes maintaining them so important. . . . As any parent knows, rewarding misbehavior only invites more of it.”11

Clearly, there is no shortage of claims by Democrats and pundits that the President of the United States acts like a toddler. For defenders of the President, these examples merely confirm their suspicion that the charge is politically motivated. Donald Trump has repeatedly labeled the mainstream media to be “fake news” and therefore “the enemy of the American people.” His defenders would argue, correctly, that previous Presidents have also been caricatured by their political opponents. Consider the opposition narratives of Trump’s most recent predecessors. Republicans depicted Barack Obama as an aloof, out-of-touch intellectual. Democrats characterized George W. Bush as an incurious simpleton, the puppet of craftier politicians. Both depictions possessed some small grains of truth but were exaggerated so badly that partisans dismissed them out of hand. It is easy for Trump’s defenders to do the same with the toddler analogy. Of course Democrats would paint him in unflattering terms; as the opposition party, they are invested in belittling a GOP President. Surely a mainstream media under constant attack by President Trump would respond with brickbats and petty insults. And #NeverTrump conservatives? To use the argot of #MAGA, butthurt media whores don’t count.

This Trumpist refutation of the Toddler-in-Chief analogy suffers from flaws, however. First, political polarization fails to explain why the caricature of Trump involves a comparison to tots. It would be a curious move for Democratic partisans to make if the charge is without foundation. Donald Trump is the oldest person ever to be elected President. Trump’s personal scandals include serial adultery, casual bigotry and misogyny, sexual assault, multiple bankruptcies, and tax fraud, all accompanied by copious amounts of profanity. Trump’s political scandals include campaign finance violations, acceptance of foreign emoluments, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power. One does not associate any of these activities with small children. Toddlers evoke innocence, and that is the last word anyone would use to describe the 45th President. Why, then, do Trump’s critics compare him to a toddler so frequently?

Second, the 45th President appears to be uniquely sensitive to accusations that he is immature. Trump has been the target of rhetorical slings and arrows for most of his adult life, but he usually revels in negative publicity. He contacted Tony Schwartz about ghostwriting The Art of the Deal after reading the critical profile of Trump that Schwartz wrote for New York magazine. As Schwartz explained in 2016, “He was obsessed with publicity, and he didn’t care what you wrote.”12 In The Art of the Deal itself, Schwartz and Trump wrote, “From a bottom-line perspective, bad publicity is sometimes better than no publicity at all. Controversy, in short, sells.”13 Despite being inured to bad press, however, Trump has been acutely sensitive to being infantilized in the press. During his time in politics Trump has taken pains to deny being a baby. In August 2016, Trump reacted badly to a New York Times story that detailed the degree of dysfunction within his presidential campaign and the tendency of his subordinates to go on television to capture Trump’s attention.14 The day after the story dropped, Trump exploded at his campaign chairman Paul Manafort, saying, “You treat me like a baby! Am I like a baby to you? I sit there like a little baby and watch TV and you talk to me?”15 Indeed, Trump views this as the worst of insults. He disparaged former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani’s cable TV defense of Trump after the Access Hollywood tape was released by saying, “Rudy, you’re a baby! They took your diaper off right there. You’re like a little baby that needs to be changed.”16 In his October 2018 60 Minutes interview with Leslie Stahl, Trump defended himself by saying—twice—“I’m not a baby.”17 Multiple press reports indicate the media narrative that incenses the 45th President the most is that “The is sometimes in need of adult daycare,” as CNN’s Jim Acosta has put it.18 If a toddler trait is to define themselves by loudly denying that they are a baby, then Donald Trump has at least one thing in common with toddlers.

Third, President Trump, his family, and his biographers have all made it clear that the 45th President is not the most mature of individuals. Trump himself told biographer Michael D’Antonio, “When I look at myself in the first grade and I look at myself now, I’m basically the same. The temperament is not that different.”19 He wrote in The Art of the Deal that “even early on I had a tendency to stand up and make my opinions known in a very forceful way.”20 Trump’s sister Maryanne told the Washington Post during the 2016 campaign that her brother was “still a simple boy from Queens.”21 Admittedly, a first-grader is older than a toddler, but the fact remains that Trump and his family agree that his psychological makeup has remained unchanged from when he was a very small boy. Most of the biographers and biographies of Trump make a similar point: Trump has experienced little emotional or psychological development since he was a toddler. Tim O’Brien, the author of TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald, warned Politico after Trump’s election that “we now have somebody who’s going to sit in the Oval Office who is lacking in a lot of adult restraints and in mature emotions.”22

The last and most powerful argument supporting the Toddler-in-Chief thesis, however, is laid out in the rest of this book. It is not only Trump’s political opponents who frequently liken him to an immature child. His closest political allies and subordinates draw the same comparison. This is the strongest rebuttal to the claim that those comparing Trump to a toddler are simply partisan hacks. Individuals with a vested interest in the success of Donald Trump’s presidency nonetheless describe him as small boy in desperate need of a time-out. They have done so repeatedly and persistently since his inauguration.

I should know. Somewhat by accident, I began collecting data on this phenomenon in early 2017, soon after Trump was inaugurated. At the time, it seemed like a lark; it did not occur to me that this trope would define Trump’s style of political leadership.

I was naive.

![]()

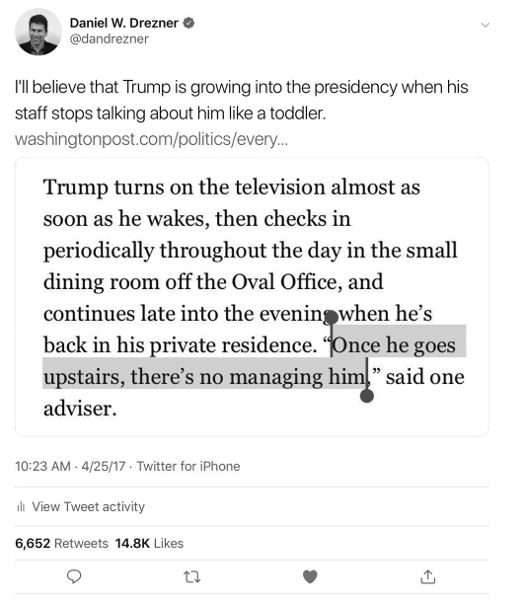

This project started innocently enough. Back in early 2017, some mainstream media commentators pushed the narrative that Donald Trump, a man with no governing experience whatsoever, was growing into the presidency. After Trump’s first address to a joint session of Congress, CNN’s Van Jones said on camera, “He became President of the United States in that moment, period.”23 A month later, after Trump addressed the nation to explain why he launched Tomahawk cruise missiles at Syria, CNN’s Fareed Zakaria told his viewers, “I think Donald Trump became President of the United States last night.”24

Perhaps these approbations arose from an understandable psychological yearning for normalcy. But they were unpersuasive. Too many stories of Trump acting like a small child and his staff acting like exasperated caregivers were floating in the ether. This became clear to me after reading a Washington Post story by Ashley Parker and Robert Costa describing Trump’s obsession with watching television. This part stood out:

Trump turns on the television almost as soon as he wakes, then checks in periodically throughout the day in the small dining room off the Oval Office, and continues late into the evening when he’s back in his private residence. “Once he goes upstairs, there’s no managing him,” said one adviser.25

There are two noteworthy aspects to this story. The first is the way that Trump is characterized as someone who needed to be managed like a toddler. The second is that the person describing Trump like an unruly child is someone with a stake in seeing Donald Trump succeed as President of the United States.

In response to that story, I tweeted out, “I’ll believe that Trump is growing into the presidency when his staff stops talking about him like a toddler.”26

A few days later, another story appeared in Politico in which the White House staff used a similar characterization.27 I tweeted that out as well, threading it below the initial tweet. Soon I noticed something: Trump’s staff and surrogates routinely and repeatedly characterized him as a toddler to the press. And so I decided to collect every example I could find of a Trump ally describing him as such.

That was three years and more than one thousand tweets ago.

As it turns out, a lot of people with a rooting interest in Donald Trump’s agenda have described him as a very immature boy. One person described NATO’s preparations for Trump’s first attendance at a meeting of the alliance as “preparing to deal with a child—someone with a short attention span and mood who has no knowledge of NATO, no interest in in-depth policy issues, nothing.”28 A Trump White House staffer characterized one dubious White House press release as an action designed solely to appease the President, “the equivalent of giving a sick, screaming baby whiskey instead of taking them to the doctor and actually solving the problem.”29 In 2017 Trump’s Deputy Chief of Staff Katie Walsh described trying to identify Trump’s goals as “trying to figure out what a child wants.”30 In 2018, a senior GOP member of Congress told Trump supporter Erick Erickson, “I don’t know what the f*** he wants and in talking to him I’m pretty sure he doesn’t know what the f*** he wants. He just wants, like a kid who’s so hungry nothing sounds good anymore and he’s just pissed off.”31 In 2019, a person close to Trump’s legal team explained the perils of advising him: “There’s just no getting through to him, and you can kiss your plans for the day goodbye because you’re basically stuck looking after a 4-year-old now.” A US official described cajoling Trump to keep troops in Syria as “like feeding a baby its medicine in yogurt or applesauce.”32

Both Secretary of Defense James Mattis and White House Chief of Staff John Kelly told officials that they viewed their job as being “babysitter” to the President.33 Indeed, during Trump’s first year in office Kelly and Mattis reportedly made a pact that at least one of them would stay in the country when Trump was in Washington, just in case he did something crazy.34 Press accounts are riddled with anonymous staff quotes like “He just seemed to go crazy today” or “He doesn’t really know any boundaries” or “Sometimes he wants to blow everything up.”35 There are so many examples of Trump’s staffers characterizing him as a toddler that even the most hardcore MAGA supporter must acknowledge that the President occasionally needs a time-out.36

Perhaps the most notorious example of a Trump official comparing him to a toddler is an anonymous September 5, 2018 New York Times op-ed penned by a senior official in the Trump administration. The author does not explicitly say that the President is a toddler, but the inference is clear. That op-ed describes Trump’s leadership style as “impetuous, adversarial, petty and ineffective” and notes that “it may be cold comfort in this chaotic era, but Americans should know that there are adults in the room. We fully recognize what is happening. And we are trying to do what’s right even when Donald Trump won’t.”37 Variations of this message from anonymous insiders have recurred throughout the Trump presidency. In the summer of 2019, a senior national security official told CNN’s Jake Tapper, “Everyone at this point ignores what the president says and just does their job. The American people should take some measure of confidence in that.”38

Some of the individuals named above have denied the quotes attributed to them. Most of the quotes that appear in this book are attributed to anonymous sources. Trump has berated the mainstream media numerous times for relying on such tactics: for example, “When you see ‘anonymous source,’ stop reading the story, it is fiction!” or “The fact is that many anonymous sources don’t even exist.”39

What makes Trump staffers, allies, and advisors stand out compared to previous administrations, however, is not their desire for anonymity. Every administration has its anonymous sources. Even Corey Lewandowski, Trump’s first campaign manager and one of his most loyal acolytes, acknowledged to the New York Times that “some of these people do exist.”40 What makes Trump surrogates stand out is the number of times they compare him to a toddler. And there are plenty of on-the-record statements from prominent Trump supporters and allies that make him sound like a rambunctious two-year-old:

- Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich: “There are parts of Trump that are almost impossible to manage.”41

- Trump White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon: “I’m sick of being a wet nurse for a 71 year old.”42

- US Senator Bob Corker: “It’s a shame the White House has become an adult day care center.”43

- GOP campaign consultant Karl Rove: “Increasingly it appears Mr. Trump lacks the focus or self-discipline to do the basic work required of a President. His chronic impulsiveness is apparently unstoppable and clearly self-defeating.”44

- Newsmax CEO and longtime Trump friend Christopher Ruddy: “This is Donald Trump’s personality. He just has to respond. He’s been so emotional. . . . It takes a toll on him, and the way he deals with it is to lash out.”45

- Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson: “I’ve come to believe that Trump’s role is not as a conventional President who promises to get certain things achieved to the Congress and then does. I don’t think he’s capable. I don’t think he’s capable of sustained focus. I don’t think he understands the system.”46

- Secretary of State Rex Tillerson: “What was challenging for me coming from the disciplined, highly process-oriented ExxonMobil corporation [was] to go to work for a man who is pretty undisciplined, doesn’t like to read, doesn’t read briefing reports, doesn’t like to get into the details of a lot of things, but rather just kind of says, ‘This is what I believe.’”47

- US Representative Ryan Costello: “The notion that a shutdown creates more pressure on Dems is toddler logic.”48

- US Senator Lindsey Graham: “The president’s been—he can be a handful—that’s just the way it is.”49

- US Representative Adam Kinzinger: “This is so beneath the office you hold. It’s childish, and yet it’s getting really old.”50

- Speaker of the House Paul Ryan: “I’m telling you he didn’t know anything about government. . . . I wanted to scold him all the time.”51

- Governor Chris Christie: “He acts and speaks on impulse. He doesn’t always grasp the inner workings of government.”52

Trump surrogates do not make these statements only to reporters; they make them under oath as well. The Mueller report confirms that when Trump aides have testified under penalty of perjury, they frequently characterize the President as possessing the emotional and intellectual maturity of a small boy. White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus told Mueller’s investigators that when Trump was angry at his National Security Advisor Michael Flynn he would pretend that Flynn was not in the room.53 Chris Christie, Steve Bannon, and White House Counsel Don McGahn all testified that Trump made requests that were “nonsensical,” “ridiculous,” or “silly.”54 Bannon, McGahn, National Security Administration head Mike Rogers, and White House Communications Director Hope Hicks all described the President having temper tantrums when informed of bad news.55 Multiple officials described similar toddler-like behavior during the House impeachment inquiry.56

Classified diplomatic cables from the British ambassador to the United States leaked to a British tabloid paint a similar picture. Sir Kim Darroch characterized Trump as “inept” and “incompetent” to the Foreign Ministry. He advised his superiors that in speaking to the 45th President, “you need to start praising him for something that he’s done recently” and that “you need to make your points simple, even blunt.” He further warned, “There is no filter.”57 All these assessments were based on Darroch’s frequent interactions with Trump’s coterie of advisors. Other diplomats based in Washington soon confirmed that Darroch’s assessments matched cables they had dispatched to their home countries.58 In response, Trump insulted Darroch repeatedly and then declared him persona non grata via Twitter, thereby confirming the ambassador’s assessment of him.59

These examples are merely a small portion of a long list. It would be one thing if these kinds of comments emerged once a quarter. Every President misbehaves on occasion. Ambitious subordinates have an intermittent incentive to leak unflattering stories about their Commander in Chief. If this trope appeared only a few times since Trump’s inauguration, that would warrant a media trend story and nothing more.

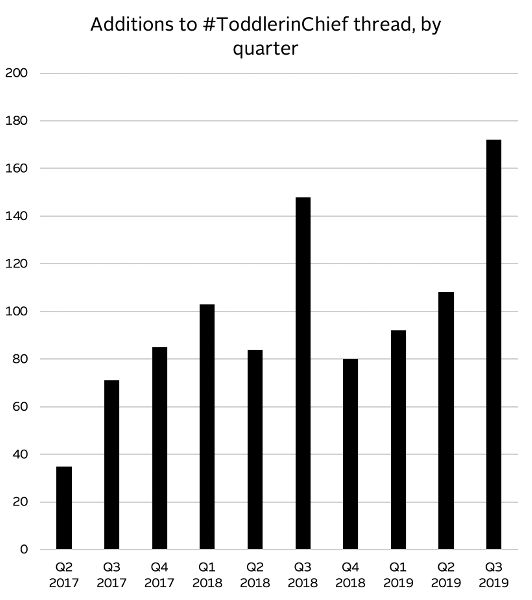

But between April 2017 and December 2019, I have recorded well over one thousand instances in which an ally or subordinate of Donald Trump has described the President as if he were a toddler.60 The rate is greater than one toddler depiction per day. That seems like a lot.

To be fair, there are elements of Trump’s toddler-like behavior that could be categorized in multiple ways. It is undeniably true that some of the behaviors described herein are not unique to small children. Teenagers can be moody and undisciplined. Adolescents, senior citizens, and overstressed parents can lose their temper. Lazy people can refuse to do productive tasks and demand to watch television instead. As will be discussed more fully in the concluding chapter, however, too many examples have surfaced during my curation of the #ToddlerinChief thread that simply do not fit any other category. Consider this anecdote from a May 2017 Time magazine profile of Trump’s after-hours life in the White House:

The waiters know well Trump’s personal preferences. As he settles down, they bring him a Diet Coke, while the rest of us are served water, with the Vice President sitting at one end of the table. With the salad course, Trump is served what appears to be Thousand Island dressing instead of the creamy vinaigrette for his guests. When the chicken arrives, he is the only one given an extra dish of sauce. At the dessert course, he gets two scoops of vanilla ice cream with his chocolate cream pie, instead of the single scoop for everyone else.61

Or this lead from an August 2019 Washington Post story:

President Trump on Tuesday abruptly called off a trip to Denmark, announcing in a tweet that he was postponing the visit because the country’s leader was not interested in selling him Greenland.

The move comes two days after Trump told reporters that owning Greenland, a self-governing country that is part of the kingdom of Denmark, “would be nice” for the United States from a strategic perspective.62

Demanding extra ice cream with one’s dessert might be the best “know it when you see it” definition of unsupervised toddlerhood imaginable. And canceling a trip because a piece of territory is not for sale sounds like a story that belongs in a children’s animated cartoon instead of the Washington Post.

None of this is to say that Trump is not capable of acting like a mature adult. There have been moments during his presidency—his first address to a joint session of Congress, his comportment at George H. W. Bush’s funeral, his 2019 D-Day commemoration speech—when he has acted “presidential.” But those moments have been few and far between. As the subsequent chapters in this book demonstrate, the toddler-like behavior has been unrelenting. Indeed, a count of additions to the #ToddlerinChief thread by quarter shows that Trump’s immature behavior is increasing, not decreasing. This matches the accounts of the Trump administration written by critical observers and staffers (such as Bob Woodward and Omarosa Maningault Newman) as well as more sympathetic portrayals by Fox News hosts and staffers (such as Howard Kurtz and Cliff Sims).63 There are simply too many of these characterizations collected by too many outlets to dismiss these reports as “fake news.”Additions to #ToddlerinChief thread, by quarter

The bulk of this book will be devoted to proving that President Trump’s behavior closely matches that of a small, bratty child. This raises an important question, however: even if Trump acts like a toddler, does it really matter? Hasn’t the system successfully contained him?

![]()

As the President of the United States, Donald J. Trump is the most powerful man in the free world. Like any modern President, however, he is also cosseted by an array of constraints. A welter of formal institutions, informal institutions, laws, and social norms have accumulated to function as a straitjacket on any individual President. These constraints started with the country’s founding. The American Revolution colored how the Founding Fathers approached the office of the presidency. The bulk of the Declaration of Independence was a list of grievances about the dangers of unchecked executive authority. The Articles of Confederation were purposefully designed with a weak executive. The Constitution established a stronger executive as one of three coequal branches of government, but the presidency is not even first among equals; Article I addresses the legislative branch, not the executive. The Constitution explicitly gives the President very few unilateral powers and endows the congressional and judicial branches with considerable abilities to check presidential overreach.64 The framers made sure that the power to tax, spend, declare war, and ratify treaties all reside with Congress. They were equally explicit in their intention for the Constitution to prevent an unconstrained presidency. James Madison noted in Federalist no. 51, “In republican government the legislative authority, necessarily, dominates.”65 Even Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for a strong presidency, stressed the importance of ensuring that the President’s powers were weaker than those of a Monarch.66

The constitutional checks on the presidency are the oldest and most revered. Beginning in the 19th century, however, an array of statutes was enacted to limit the powers of the President even as the executive branch grew. American political development scholars stress the erosion of patronage power and the rise of civil service protections as additional checks on presidential caprice.67 As voters demanded that the federal government provide more public goods, the bureaucracy expanded and professionalized itself to be able to consume and produce policy expertise. In domestic affairs, the Progressive Era, the New Deal, and the Great Society programs increased the size and scope of the federal bureaucracy. The Second World War, the Cold War, and the Global War on Terror concomitantly expanded the foreign policy bureaucracy. It could be argued that the creation of new regulatory agencies and cabinet departments empowers the President vis-à-vis the legislative branch. Even if housed in the executive branch, however, Congress authorized them with statutes that strictly demarcated the limits of direct presidential influence. The ability of presidents to order these agencies to execute their every whim is further constrained by laws like the Administrative Procedures Act. Statutes prevent President Trump from firing his Federal Reserve Chairman—even though he has repeatedly expressed his desire to do so.68 Furthermore, each new bureaucracy has developed its own norms, procedures, and cultures. These make it difficult for Presidents to order executive agencies to take actions that contravene these practices. Jimmy Carter, hardly an advocate of enhanced presidential powers, lamented to the New York Times in 1977 that “I underestimated the inertia or the momentum of the federal bureaucracy. . . . It is difficult to change.”69

Beyond abiding by black-letter constitutional law and statutory restrictions, Presidents have long been expected to behave in accordance with unspoken norms and customs. Some political scientists describe these practices as “informal institutions”: unwritten but socially shared rules that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of laws or official channels.70 Julia Azari and Jennifer Smith have explored how these informal institutions play vital roles in supplementing gaps in formal rules or ameliorating possible contradictions in rules. They note that even if these norms are not codified, “political actors in the United States do, in fact, alter their behavior in accordance with unwritten rules.”71 The growing role of professional expertise in governing also acted as an additional guardrail. The presence of acknowledged experts in the government can constrain the President. Defying an expert consensus on an issue in which expertise is valued would traditionally be viewed as politically costly.72 The combination of statutory restrictions, bureaucratic autonomy, and informal institutions explain why Barack Obama said immediately after the 2016 election, “One of the things you discover about being President is that there are all these rules and norms and laws and you’ve got to pay attention to them. And the people who work for you are also subject to those rules and norms.”73

The accumulation of all these constraints is why so many presidential scholars have argued that the presidency is a fundamentally weak institution. Richard Neustadt remains the most widely cited scholar on the presidency. In his magnum opus, Presidential Power, he argues that the President’s chief power is the ability to persuade other actors—members of Congress, members of the executive branch, and the American people—to act in accordance with presidential preferences. Without the ability to persuade, Neustadt suggests, the President’s powers are feeble: “In form all Presidents are leaders nowadays. In fact this guarantees no more than that they will be clerks.”74 Successive generations of scholars have echoed this point. Terry Moe and Will Howell, for example, argued as recently as 2016 that the Constitution has excessively hampered the ability of the President to solve problems. They advocate for a stronger presidency because, in their words, “The Constitution sees to it—purposely, by design—that [Presidents] are significantly limited in the formal powers they wield and heavily constrained by the checks and balances formally imposed by the other branches.”75

Donald Trump posed an excellent test of these theories of institutional constraint. In 2016 many people were saying that he was unfit to occupy the office of President of the United States. His behavior during the campaign ranged from petulant to racist. His behavior during the transition period ran the gamut from petty to unethical. Trump’s inauguration address—which was, in retrospect, one of his more coherent speeches—was so far outside the norms of the presidency that even George W. Bush described it as “some weird shit.”76 Nonetheless, many commentators believed that Congress, the courts, and the bureaucracy would tie him down like Gulliver.77

As it turns out, most of these arguments have not held up. Unfortunately, someone with the emotional maturity of a small child was elected to an office that, over time, had been designed for the last adult in Washington, DC.

![]()

Why has Donald Trump tested the guardrails of the American political system in ways that his predecessors did not? Even a cursory review of past Presidents reveals a few great men, some good men, and a mélange of liars, cheats, fools, drunks, depressives, and racists. Every President prior to Trump has been accused of some scandal or act of malfeasance.78 The modern American presidency has seen philanderers (Kennedy, Clinton), bullies (LBJ), bumblers (Ford, George W. Bush), eggheads (Carter, Obama), and paranoids (Nixon) occupy the office. Despite this rogues’ gallery, the Republic has survived and thrived. Is Trump really so different?

Most of this book will argue yes, Trump really is different. Equally important, however, is that the times are different. The checks and balances constraining the presidency have worn thin.

Growing dysfunction in other spheres of political life has shifted greater power to the executive branch. Each time efforts have been made to curb the power of the presidency—immediately after the Civil War, in response to the Progressive Era, after Watergate—the presidency has struck back. Historian Arthur Schlesinger wrote about this phenomenon in The Imperial Presidency: “Confronted by presidential initiatives in foreign affairs, Congress and the courts, along with the press and the citizenry, often lack confidence in their own information and judgement and are likely to be intimidated by executive authority.”79 This growing power of the presidency predates Trump by several decades; many observers are only now grasping the problem.

Consider the formal checks and balances. While some might argue that the Constitution imposes significant checks on the executive branch, history offers a different guide. The presidency has, for the past century plus, amassed an increasing array of formal and informal powers. As the head of the executive branch, the President now possesses several ways to act without consulting the other branches of government. These include executive orders, executive agreements, presidential proclamations, presidential memoranda, signing statements, declarations of states of emergency, and national security directives.80 As American history has unfolded, Presidents have availed themselves of these forms of direct action at an accelerating rate. Political scientist William Howell concludes, “The president’s powers of unilateral action exert just as much influence over public policy, and in some cases more, than the formal powers that presidency scholars have examined so carefully.”81 Presidential scholar Julia Azari concurs:

Congress has the power of the purse and to declare war, as well as a role in the foreign policy duties of the president (like the requirement for the Senate to ratify treaties). Yet the structure of the government puts the president in a position to both make decisions and articulate them in a way that Congress rarely can. . . .

The government structure created by the Constitution allows the president a great deal of power and flexibility. The text does very little to describe the nature of this power or its limits, leaving presidents free to do what they can get away with politically much of the time.82

Another reason constitutional checks and balances have eroded is that the other branches of government have voluntarily ceded some of their authority to the executive branch. This has been most evident in foreign relations, which was the wellspring of Schlesinger’s concerns about an imperial presidency.83 Congress has not formally declared war since 1942, but that has not stopped the President from using military force hundreds of times, including in Korea, Vietnam, Panama, and Afghanistan, and twice in Iraq.84 Presidents have relied on the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force passed in the wake of the September 11 attacks to justify the use of force in Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. Congress has demonstrated neither the will nor the capacity to claw back those powers.85 The vast system of alliances has further empowered the President to deploy military forces without consulting Congress.86 Similarly, after passing the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930, Congress decided it could not responsibly execute its constitutional responsibilities on trade.87 Over the ensuing decades, it delegated many of those powers to the President, marking the beginning of a sustained decline in congressional influence over foreign economic policy.

On questions of oversight, congressional power has eroded badly. The number of hearings on foreign policy issues has declined precipitously.88 Members of Congress simply lack the electoral incentive to devote time and energy into national security and foreign policy concerns.89 After Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America, Congress handicapped itself further by reducing its own staff and resources. This has weakened its ability to rely on expertise independent of the executive branch. Again and again, Congress has eschewed responsibility and delegated authority to the President. As William Howell concludes, “The notion that a watchful Congress will rise up and snub any President who dares challenge it could hardly be further from the truth.”90

Political polarization has further debilitated Congress, encouraging the expansion of presidential powers.91 Over the past 50 years, Democrats in Congress have shifted to the left, and Republicans have shifted way, way to the right.92 As partisanship has paralyzed Congress, the legislature has become less able to pass significant legislation beyond funding the government. Over time, Presidents have simply seized more power in response to a dysfunctional legislative branch. They have done so secure in the knowledge that the very polarization that stymies Congress also prevents it from responding effectively to presidential power grabs. Presidents, even unpopular ones, can count on party loyalists in Congress to block measures that would constrain or reverse presidential overreach. Unsurprisingly, political scientists have found that Presidents are both more likely and more able to act unilaterally when the legislative branch is paralyzed by polarization. Andrew Rudalevige concluded in The New Imperial Presidency that increased partisan polarization “enhanced the incentives for the President, whoever the incumbent, to claim unilateral authority and make it stick.”93

This phenomenon has been particularly salient during the 21st century, as polarization within Congress has skyrocketed to new highs. Both the Bush and Obama administrations stretched the boundaries of executive power before Donald Trump was sworn into office. The Bush administration expanded the federal government’s powers to monitor communication and financial transactions, as well as indefinitely detain enemy combatants. The Obama administration used executive orders to enable the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate greenhouse gas emissions and grant work permits to illegal immigrants. President Obama negotiated international agreements on climate change and the Iranian nuclear deal using executive authority alone. Ironically, before he was President, Trump criticized Obama repeatedly for executive overreach. This changed quickly after January 20, 2017. Trump soon bragged that he had issued more executive orders than Obama in his first hundred days.94 In 21st-century America, presidential ambition does not just check congressional ambition, it checkmates it.

As for the judicial branch, the courts demonstrated considerable deference to the executive branch long before Trump came on the political scene. Part of this reflects a sense of self-preservation. Judges have no enforcement power and are therefore understandably reluctant to referee disputes between the congressional and executive branches. They have developed legal rationales, such as the political questions doctrine, to avoid hearing challenges to the President. Analyses of judicial rulings on questions of executive branch overreach reveal that the courts have largely refrained from directly confronting the President. When they do rule on challenges to presidential power, they side with the President more than 80 percent of the time.95 Furthermore, even when federal courts have ruled against the President, they have done so in as narrow a manner as possible. The result has been that the President has amassed significant levers of power with fewer checks and balances than Americans commonly realize.

A similar story can be told with respect to the executive branch’s constraints on the presidency. A web of bureaucratic units ranging from the Office of Management and Budget to the US Trade Representative to the National Security Council staff are housed within the Executive Office of the President. Each of these organizations has grown much more quickly than the relevant cabinet agencies. The autonomy of cabinet officers has also shrunk over the last half-century. Beginning with the Reagan administration, Presidents have exerted greater control over subcabinet appointments across the federal government. The White House has taken care to oversee political cabinet appointments at the Deputy Secretary, Undersecretary, and Assistant Secretary level.96 The political loyalties of these appointees lie with the President rather than their cabinet Secretary.

The autonomy of the federal bureaucracy was under assault well before the Toddler in Chief was inaugurated. Beginning with the Nixon administration, successive Presidents learned how to shape the permanent bureaucracy in accordance with their policy preferences.97 The expansion of political appointments and executive orders have made it easier for the President to dictate to executive agencies. More recently, elected officials have starved the bureaucracy of manpower. Post-2008 hiring freezes within the federal government ensured that the median age of a federal bureaucrat was higher than that of the private-sector workforce.98 Still, the Trump administration has accelerated this phenomenon by taking actions to weaken the autonomous power of the civil service. During the interregnum between Obama and Trump, the latter’s transition teams walled themselves off from high-ranking career professionals in numerous cabinet agencies (when they bothered to show up at all).99 One month into the Trump administration, White House Advisor Steve Bannon proclaimed a daily war aimed at the “deconstruction of the administrative state.”100 President Trump has gone further than his predecessors to intrude into the areas of the executive branch—military justice, the intelligence community, the Justice Department—that are supposed to be insulated from White House interference.

The breakdown of these formal guardrails extends to the more informal ones, such as deference to the opinions of experts. For this to matter, expertise must be held in high esteem. Well before Trump, however, there had been a steady decline of trust in authority and expertise.101 Over the past half-century there has been an erosion of public trust in almost every major public institution. The public opinion data showing rising levels of pessimism toward major institutions and professions is incontrovertible. Whether one looks at polling data from Gallup, Pew, the General Social Survey, or other sources, faith in the federal government has plummeted. Gallup also polls Americans about their belief in other institutions: local police, unions, public schools, organized religion, business, and the health care system. The results for all are the same: a secular trend of rising distrust. Similarly, trust in major sources of information—including television news and newspapers—is also at an all-time low.102 Trust in professional journalists also declined over the past decade, falling well below that for chiropractors.103 The General Social Survey data show a similar loss of confidence in expert communities such as scientists and educators.104 In essence, suspicion of every institution in the United States has risen in this century, with the exception of the military. Unfortunately, the ability of experts to kill harebrained ideas ain’t what it used to be. Indeed, this very distrust contributed to the political rise of Donald Trump in the first place.

The informal norms designed to regulate political behavior have also faded. Even before Trump, rising levels of partisanship had permitted politicians on both sides to escalate the level of vitriol toward the opposing party. Conspiracy theories bled into mainstream political discourse. Without foundation, Hillary Clinton was suspected of orchestrating the murder of a White House staffer. George W. Bush was accused without any evidence of being responsible for the September 11 terrorist attacks. Politicians hit by scandals learned that if they could tough out the initial wave of shock and disgust, they could often retain their office. Trump’s very election eviscerated many of the norms of political behavior. He shot to prominence in far-right Republican circles by questioning whether Barack Obama was born in the United States. While running for office, Trump denigrated ethnic minorities and Gold Star families. The Access Hollywood tape revealed his demeaning attitude toward women. In one presidential debate he told Hillary Clinton that she would face prosecution if he was elected. Despite all these norm breaches, Trump won the 2016 presidential election. As President, he has been unconstrained by the traditional norms of the presidency.

Each of these guardrails checking presidential power had begun to fail before Trump was elected President. During his tenure, they have almost completely broken down. As I discuss further in the concluding chapter, the Toddler in Chief is like most other toddlers—bad at building structures but fantastic at making a complete mess of existing ones.

![]()

Institutionalists have been warning about the breakdown of democratic guardrails for quite some time. An optimist might have fretted about these trends but noted that everything would be okay so long as the President acted like, you know, a grown-up—someone who recognized that with great power comes great responsibility. Unfortunately, Donald Trump really does think and act like a toddler. He has done so for most of his life.

Beyond the checks and constraints studied by political scientists, pundits gravitated toward two additional “guardrail narratives” in the early months of the Trump administration. The first was that he would grow into the office of the presidency. Trump himself promised this during the 2016 campaign, stating repeatedly that he would be “so presidential you will be so bored.”105 At key junctures in Trump’s first months as President, if he demonstrated even a hint of maturity, commentators would describe it as the moment when Trump truly became the President.

Republicans relied on a variation of this line of argument during Trump’s first year in office. When news broke of Trump violating a norm or possibly a law, fellow Republicans often explained it away as “the actions of a political newcomer unfamiliar with what is appropriate presidential conduct.”106 The implication, of course, was that as Trump moved down the learning curve as President, he would engage in this kind of transgressive behavior less frequently and comport himself in a more presidential manner.

The other guardrail narrative was that even if Trump behaved erratically, he had surrounded himself with advisors and cabinet members who would function as an “Axis of Adults” to constrain the Commander in Chief.107 While many Americans questioned Trump’s maturity, no one viewed Gary Cohn, John Kelly, James Mattis, H. R. McMaster, or Rex Tillerson as immature. Political scientists put great stock in the power of advisors to shape and mold a President’s thinking on vital issues.108 Sure, Trump might rant and rave, the thinking went, but “the Generals” would rein him in. The core thesis of the anonymous New York Times op-ed by a senior Trump official was that there would be adults in the room to constrain Trump.

These narratives sounded savvy and knowing in 2017. They were designed to allay the fears of Americans anxious about President Trump. In retrospect, however, they were naive. Trump has not crashed the economy or started a nuclear war. However, as this book will take pains to demonstrate, there is simply no getting around the point that President Donald Trump has acted an awful lot like a badly behaved toddler, and there is little his staff has done to contain his outbursts.

The Toddler in Chief has failed to mature even in areas that ostensibly cater to his professed base. Trump has proclaimed that he is the biggest booster of the military and that the uniformed services support him. Yet he has done nothing to better understand his role as the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. The 45th President has restricted his encounters with the families of those killed in action because he finds the experience to be too intense.109 Despite repeatedly calling the top brass at the Pentagon “my generals,” the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff upbraided him for unproductive interventions in national security meetings.110 Colonel David Lapan, a retired Marine who served as the spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security during the first year of the Trump administration, told the New York Times, “There was the belief that over time, he would better understand, but I don’t know that that’s the case. I don’t think that he understands the proper use and role of the military and what we can, and can’t, do.”111 Trump’s former Secretary of the Navy acknowledged that “the President has very little understanding of what it means to be in the military, to fight ethically or to be governed by a uniform set of rules and practices.”112 Military officers have expressed increasing discomfort with Trump’s use of the uniformed services as a partisan prop.113

Furthermore, Trump’s Axis of Adults proved unable to rein in his toddler-like behavior. In the fall of 2017, Senator Bob Corker talked to reporters about “the tremendous amount of work that it takes by people around [Trump] to keep him in the middle of the road.” Referencing White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and Secretary of Defense James Mattis, Corker concluded that “as long as there are people like that around him who are able to talk him down when he gets spun up, you know, calm him down and continue to work with him before a decision gets made, I think we’ll be fine.”114 All of these people saw their authority denuded by the Toddler in Chief.115 Indeed, like burned-out nannies, most of them have resigned. Many others have been fired. By the start of Trump’s third year in office, all of them had left government service, along with Corker. As former Trump White House staffer Cliff Sims told Politico, “What we are seeing is the erosion of the presidency to where what is left is just the president.”116

One can hardly blame the staff for the high burn rate. Normal parents shepherd their children through the terrible twos for only a short spell. Trump’s advisors are required to deal with a Commander in Chief who will never really grow up. Furthermore, the standard means of exercising authority in a childcare setting are unavailable to the White House staff. He is the President of the United States; in the end his staff must obey Trump’s dictates, resign in protest, or wait to be fired.

It does not matter whether Trump has been at the job for two years, or four, or six; he will never grow into the presidency. He is who he is, which happens to be the essence of a petulant child. In the first year of Trump’s presidency, one diplomat in Washington told the Washington Post, “The idea that he would inform himself, and things would change, that is no longer operative.”117 Two years later, a G-7 diplomat described coping with Trump’s behavior: “You just try to get through the summit without any damage. . . . Every one of these, you just hope that it ends without any problem. It just gets harder and harder.”118 Even Trump’s closest advisors acknowledge that he has not matured into the office. Chapter 8 will demonstrate that they have instead seen a devolution in his behavior.119 As one April 2019 Politico story surmised, “Even some former administration officials who admire the president and his policies acknowledge that he does not pay attention to traditional rules of the government and often does not know the legal boundaries of his job since he’s only two years into his term. . . . They perceive that Trump’s impatience with the obstacles standing in his way has only increased in recent months as he’s grown more comfortable in the office.”120 If anything, Trump’s toddler traits have become more visible over time.

Trump’s enablers now justify his transgressive behavior by extoling him as an “untraditional” President. When it was revealed that 60 percent of Trump’s daily schedule was unstructured “Executive Time,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders responded, “President Trump has a different leadership style than his predecessors and the results speak for themselves.”121

![]()

This book is divided into eight chapters. The first seven examine different dimensions of Trump’s toddler-like traits. This includes behavior ranging from Trump’s temper tantrums to his poor impulse control to his short attention span to a potpourri of childlike habits. Chapter 8 takes a closer look at how Trump’s aides, subordinates, and supporters have coped with staffing the Toddler in Chief. Spoiler alert: the answer is, not well. The conclusion considers what it means for the country to have a Toddler in Chief and what can be done to prevent worst-case scenarios—including future Toddlers in Chief.