Health Basics, Part 1

WELLNESS

GREAT-GRANDMA’S CHICKENS WERE KEPT AS LIVESTOCK

and their days were numbered. Their primary purpose was to feed the family both eggs and meat. They were not named or doted upon. After their prime egg-laying days had passed, they filled the freezer for the coming year’s meals. If they were sick or injured, they became the guests of honor at Sunday dinner. But times have changed.

Many chicken keepers would gladly compensate a veterinarian for the same quality of medical care their other pets enjoy. Unfortunately, the historical lack of demand for small-flock health care means that trained, experienced poultry veterinarians are rare ducks. Petey is a female Black Araucana chick.

When our birds are sick and we don’t know where to turn, it’s tempting to trust advice from anyone with five minutes more experience than us. Don’t be fooled by specious claims that you can prevent diseases and cure what ails your chickens with garlic, herbs, diatomaceous earth, or vinegar. There are no shortcuts to chicken health.

Today’s backyard chickens are kept primarily as pets and for eggs; they are given names and invitations to live out their natural lives as beloved family members without regard to their declining productivity. When they are sick or injured, their chicken keepers tend to them and try diligently to find them qualified medical care providers. Many chicken keepers would gladly compensate a veterinarian for the same quality of medical care their other pets enjoy, but unfortunately, the historical lack of demand for small-flock health care means that trained, experienced poultry veterinarians are rare ducks.

Very few practicing veterinarians, including avian vets, complete coursework in poultry anatomy, physiology, or disease. There are currently fewer than three hundred diplomates certified by the American College of Poultry Veterinarians (ACPV), nearly all of whom work in government, academia, or the commercial poultry industry. The work of keeping commercial flocks healthy and productive has resulted in an abundance of scientific insight about flock management best practices for commercial poultry farms, but very few resources have been committed to studying issues specific to small laying flocks.

When our birds are sick and we don’t know where to turn, it’s tempting to trust advice from anyone with five minutes’ more experience than us. Don’t be fooled by specious claims that you can prevent diseases and cure what ails your chickens with garlic, herbs, diatomaceous earth, or vinegar. There are no shortcuts to chicken health. White Silkie Freida tends to her adopted chick.

But there is reason for hope! Sources in the ACPV tell me they are optimistic that it will become common for vets to begin seeing backyard chickens in the next 5 to 10 years. Until then, we will remain our chickens’ primary health care providers and advocates.

The steady increase of U.S. households keeping chickens over the past 15 years, coupled with the scarcity of specialized avian veterinary care, has resulted in a proliferation of folklore generated by laypeople to fill the poultry health care void. There is no shortage of bush leaguers offering dubious or unintentionally dangerous advice. When our birds are sick and we don’t know where to turn, it’s tempting to trust advice delivered in clever sound bites from anyone with 5 minutes’ more experience than us. Don’t be fooled by specious claims that you can prevent diseases and cure what ails your chickens with garlic, herbs, DE, or vinegar. There are no shortcuts to chicken health.

Until the supply of poultry veterinarians catches up with the demand for their services, backyard chicken keepers need to work a little harder at finding health care resources. Contact all the veterinarians in your area to ask whether they treat chickens. In addition, a variety of state and federal resources are available to assist backyard chicken keepers in different capacities. These include state veterinarians, veterinary diagnostic laboratories, USDA state poultry extension specialists, and poultry veterinarians through the USDA’s Veterinary Services office.

Simple Steps for Healthy Hens

Whether or not we have access to a poultry veterinarian, we are able to significantly influence the health of our chickens by focusing on basic principles of good flock management. There are no gimmicks or shortcuts to keeping chickens healthy and preventing disease. This means providing a complete commercial ration, limiting treats and stress, offering clean water in clean containers, maintaining plenty of clean, dry living space, and observing good biosecurity practices. Please refer to the appropriate chapters for more in-depth discussions and recommendations on each of these topics.

The term biosecurity refers to the steps we take to protect our flocks from infectious diseases. Everyone approaches biosecurity differently, guided by personal risk tolerance, but implementing even the most basic biosecurity measures can significantly limit potential health threats to a flock.

For sanitizing as a biosecurity measure, I use unactivated Oxine to disinfect shoes and equipment, at the rate of 1/4 teaspoon per gallon of water. Alternatively, use 1/4 to 1/2 cup Clorox-brand bleach per gallon of water. This is Marilyn, a White Orpington.

A chicken’s complex immune system defends it from pathogens that have the potential to cause infectious disease. How well its immune system responds to an attack depends on the bird’s age, health, and the strength and concentration of pathogens encountered. Different types of stress weaken the ability of a chicken’s immune system to fight infection. Stress can be in the form of overcrowding, dietary deficiencies, temperature extremes, misuse of medications or dietary supplements, rough handling, and predator attacks.

But even healthy chickens don’t stand a chance of remaining healthy if we schlep pathogens into their yard. Potential disease carriers include you and other poultry keepers, clothing, shoes, equipment (shovels, tractors, wheelbarrows, car tires), and all wildlife, including predators and pests. Limit potential disease carriers from entering the chicken yard from high-risk locations, including all other chicken yards, poultry swaps, poultry shows, livestock auctions, farms, fairs, and feed stores.

BIOSECURITY BEST PRACTICES

• Require visitors from high-risk locations to wash their hands, change their clothing, and sanitize footwear or use dedicated rubber-soled footwear before entering your yard. Take the same precautions when returning home from high-risk locations and after caring for chickens in isolation.

• Disinfect feeders and waterers regularly.

• Empty, clean, and disinfect coops at least annually.

• Don’t attract wild birds to the area with bird feeders or birdbaths.

• Control the rodent, fly, and wild bird populations in and around the chicken yard.

• Obtain necropsies (postmortem exams) when birds die of unknown causes.

• Never add birds exhibiting symptoms of disease to your flock.

• Chickens from other yards can be recovered carriers of disease—it’s safest not to bring them into your flock at all, but if you must, quarantine properly.

It’s safest not to bring new birds into a flock at all. If you choose to accept the risk, it’s very important to implement proper quarantine procedures. A chicken that appears perfectly healthy can be a disease carrier. In addition, during times of stress, such as moving from one home to another, latent diseases can become active, causing birds to exhibit symptoms of illness and shed pathogens, actively infecting other chickens.

A quarantine period provides the opportunity to watch for parasites and symptoms of illnesses as they emerge before exposing the rest of the flock. Failure to quarantine properly can result in the death of all the birds. To quarantine properly, follow these recommendations:

• Keep new birds at least 12 yards away from the existing flock. Some diseases, such as Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG), can travel in the air.

• Keep new birds confined and isolated in a dedicated coop, pen, or other suitable housing area.

• Don’t share equipment, clothes, shoes, feeders, or waterers between the new birds and the existing flock. For example, do not feed the new birds and then walk through the existing flock in the same, unsanitized shoes.

• The longer a bird is in quarantine, the greater the opportunity for diseases to manifest themselves and be detected. Three weeks is the bare minimum recommendation; 30 to 60 days is better.

• During quarantine, testing can be performed (e.g., fecal float testing for worms, blood work for other communicable diseases) and a lice or mite infestation can be identified and treated.

• Observe new birds for signs of illness, including coughing; sneezing; gurgling; red, swollen, or watery eyes; eye or nasal discharge; paralysis of legs and/or wings; discolored combs/wattles; drowsiness or depression; uncoordinated movements; lack of appetite or failure to drink; and unusual droppings (bloody, worms, diarrhea).

• Never add birds exhibiting signs of illness to an existing flock.

• If the quarantine period expires and all the new birds appear healthy, they can be integrated gradually into the existing flock (see chapter 9).

Even when all these precautions are taken, they are still not foolproof because chickens raised in different places can develop different sets of immunities. A perfectly healthy chicken raised in one flock and then moved to a different flock can transmit a disease (to which it has developed immunity) to the new flock (lacking the same immunity due to lack of prior exposure), and vice versa.

Let’s focus on what will be useful to your flock: your ability to recognize signs of a problem, knowing how to safeguard sick and healthy birds, and finding professional help when necessary. This Black Copper Marans hen is exhibiting the typical appearance of a sick chicken.

Recognizing Illness and Injury

Without a vet to examine your sick chicken, it’s useless to worry about all the possibilities. For example, nearly a dozen respiratory diseases share similar symptoms that even a poultry vet cannot distinguish among without lab tests.

So rather than take you on a tour of Diseaseville, let’s focus on what will be useful to your flock: your ability to recognize signs of a problem, knowing how to safeguard sick and healthy birds, and finding professional help when necessary. Chapter 8 will focus on specific problems and their treatments.

HOW TO HOLD A CHICKEN

Holding a chicken correctly allows you to examine it easily and keep it calm. It also keeps the pooping end of the bird as far away from you as possible!

With the chicken’s beak facing you and your palm facing up with fingers spread apart, slide your index finger between the legs. Allow the keel bone to rest on your palm and forearm. Wrap your pinky, ring finger, and middle finger around one thigh while the thumb holds the other thigh.

It is easiest to examine a chicken after dark when roosting. I use a headlamp and enlist help from a partner whenever possible. A bath is another good opportunity to get a closer look—after the initial surprise of being placed in water, most chickens love baths (though they should be bathed only when necessary). If neither such opportunity is convenient, keep a bird calm by loosely wrapping it in a towel, covering its head and eyes while ensuring ample breathing room.

Use a small scale to weigh birds periodically, making note of weights for future comparison. An adult chicken like this Serama hen should maintain a consistent weight.

This Columbian Wyandotte hen has a red comb and wattles; clear, moist, round eyes; and clean nares that are free from discharge.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Chickens are masterful at concealing illness and injury until they are in dire straits, but by spending time observing and handling your birds, you will be able to pick up on subtle signs as early as possible. A healthy bird is alert and active, eating and drinking, scratching and pecking throughout the day with periods of dust bathing and resting in between. It will not sit in the same spot for hours at a time or fail to react when approached. A healthy chicken should not limp, have labored breathing, avoid food, drink excessively, lose weight, or hide. Investigate any change from normal behavior and appearance.

Suppose one of your chickens isn’t behaving quite right. Now what? Begin troubleshooting with this head-to-toe chicken checkup:

1. Weight: Use a small scale to weigh birds periodically, making note of weights for future comparison. An adult chicken should maintain a consistent weight. Weight loss may indicate illness, worms, coccidiosis, malnutrition, or bullying by birds blocking access to feed. Weight gain indicates overfeeding, usually by way of treats, snacks, and kitchen scraps.

2. Combs and Wattles: The comb and wattles should be red and correct for the breed. If a chicken’s normal comb is usually upright, it shouldn’t be flopped over; if it’s usually full or plump, it shouldn’t be shriveled. The comb and wattles should not be pale, purple, or ashy, or have lesions or scabs, which can indicate fowl pox, frostbite, pecking injuries, or a fungal infection known as favus. A pale comb can be normal for a broody hen, a molting chicken, chickens in very cold weather, or a pullet that has not yet begun laying eggs.

3. Eyes: Eyes should be clear, bright, round, and moist. The pupils should be round and equal in size, and react to light. The eyes should not be sunken, swollen, cloudy, watery, crusty, bubbly, or contain any type of discharge.

4. Nares: A chicken’s nostrils should be clean and free of discharge or crust.

5. Beak: A normal beak is smooth, free from cracks, and closed most of the time. An open beak can indicate stress or overheating. The upper mandible is slightly longer than the lower and should be aligned directly above it. Any sudden change in alignment is abnormal. Chips, breaks, or overgrown beaks should be honed by filing. Scissor beak (a.k.a. crossed beak) is a common deformity that does not occur suddenly (see chapter 5).

6. Mouth: There should be no foaming, discharge, squeaking, honking, or labored breathing. The inside of the mouth should be free from lumps, lesions, and discoloration. Wet fowl pox and mold toxicity are common causes of cheesy-looking lesions inside the mouth. The breath should not smell foul, a common indicator of sour crop. The roof of the mouth is split, and the divide in the hard palate (the choanal slit) should be clear and unobstructed.

7. Feathers: Plumage should be shiny and follow the contour of the body except in birds with a genetic trait for frizzled feathers that grow out and curl away from the body. Broken, bloody, or frayed feathers can indicate behavioral problems in the flock, stress, parasites, nutritional deficits, or rodent problems. A high-production layer can have ragged-looking feathers toward the end of her production cycle until molting. Know what molting looks like (see chapter 9) and the age and season to expect it, as well as what pinfeathers look like.

8. Skin: Part feathers all over the body to inspect the skin, which should be free from mites, lice, maggots, scabs, lacerations, lumps, and bruises.

9. Breast and Keel: The breast should be firm and free of blisters. The keel is the bone in between the breast muscles, and it should be straight. It should not be bony or protrude (which can indicate weight loss), be difficult to feel, or be padded with fat.

10. Wings: A chicken’s wings should be free from cuts, swelling, and injuries. The armpit area underneath the wing should be free of insects.

11. Abdomen: The abdomen should be firm, not hard, swollen, or squishy like a water balloon. An abnormal abdomen may signal egg yolk peritonitis, an oviduct infection, heart failure, or a number of other serious issues requiring veterinary care.

12. Preen Gland: Located where the tail meets the back, this little nub should not appear blocked or swollen. The skin surrounding it should be free of parasites.

13. Vent: On a laying hen, this orifice should be clean and moist but not wet. There should be no scabbing, insects, blood, discharge, or accumulations.

14. Legs, Feet, and Toes: Scales on a chicken’s legs and feet should be smooth and lie flat. Raised, flaky, or crusty-looking scales can indicate a mite problem. Feet and legs should be free from swelling, lesions, and scabs. Nails should be a reasonable length and trimmed or filed if they interfere with walking.

15. Poop: Often one of the first signs of a health problem is a change in the appearance of droppings. Normal chicken poop spans a wide range of colors and textures, which can make it tricky to identify abnormal poop.

Buff Orpington hen. Plumage should be shiny and follow the contour of the body, except in birds with a genetic trait for frizzled feathers that grow out and curl away from the body.

Located where the tail meets the back, the preen gland should not appear blocked or swollen. The skin surrounding it should be parasite-free.

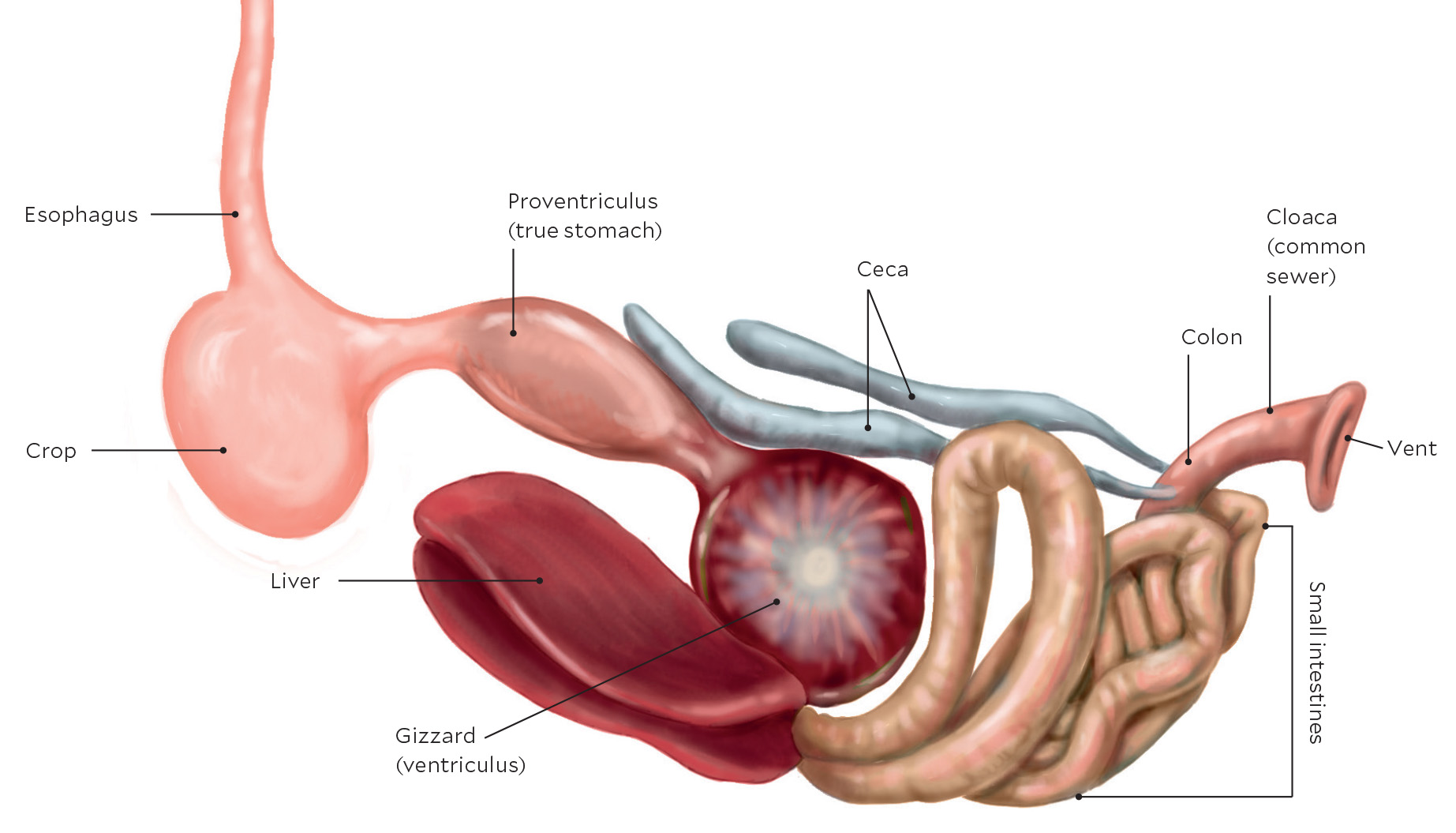

CHICKEN DIGESTIVE TRACT

NORMAL CHICKEN POOP

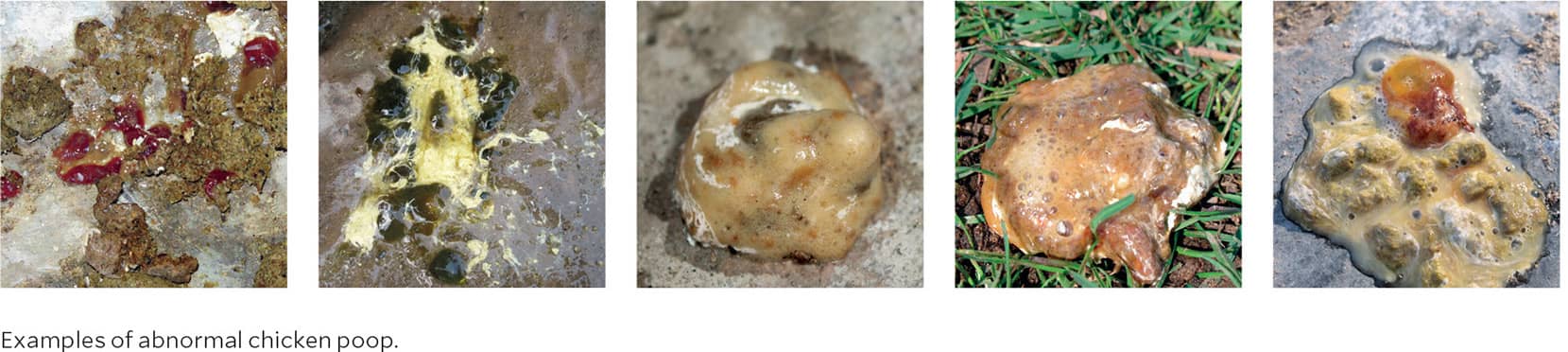

ABNORMAL CHICKEN POOP

THE SCOOP ON POOP

Understanding the journey food takes through a chicken’s body helps us better appreciate the end result. Food and water travel from the mouth, down the esophagus, and into the crop, where it’s stored before passing into the stomach (proventriculus). There, acid and digestive enzymes are added before the food moves into the gizzard (ventriculus), where it is ground up before moving into the intestines.

Ceca branching off the small intestine absorb water contained in the food. The ceca ferment matter not previously broken down in the digestive tract and empty their stinktastic contents several times a day. Cecal poop resembles really disgusting pudding and can range in color from yellow to black.

The last stop in the digestive tract is the cloaca. Here, the contents that have passed from the intestines combine with urates. Chickens don’t have a bladder, so they eliminate waste products from the urinary system inside the body in the form of uric acid, which appears as a white cap on the top of the feces. These waste products exit the body through the cloaca (as do eggs).

Unusual droppings may signal illness or parasites, or can be caused by something the chicken ate. Too much protein in the diet can cause diarrhea. The consumption of large amounts of water causes watery droppings, which is normal in hot weather, but not otherwise. Black oil sunflower seeds can cause black poop and purple cabbage causes blue poop.

A broody hen with aspirations of hatching chicks leaves her nest to relieve herself once or twice a day instead of taking a dozen or more bathroom breaks throughout the day. As a result, broody poop is gargantuan.

The occasional appearance of bits of pink tissue in droppings from an adult hen is ordinarily from normal shedding of intestinal lining, but blood in the poop is never normal. Yellow, foamy, greasy-looking, watery, or dark green droppings are all abnormal and should be tested for parasites (see chapter 8).

TRIMMING NAILS AND SPURS

Chickens’ nails and roosters’ spurs are similar to human and dog nails in that they continue to grow and require maintenance. Backyard chickens can usually maintain the length of their toenails through normal activities, but some chickens can’t because of awkward anatomical positioning or from being housed on wire floors or soft litter. In such cases, trimming, clipping, or filing is needed to prevent lameness or injury.

The basic tools needed to trim nails are styptic powder, paper towels, a nail file, and dog nail clippers, either guillotine- or plier-style clippers with a safety guard.

Chickens’ nails contain veins that will bleed if the nail is cut too far back. Always trim conservatively to avoid nicking the vein and keep styptic powder handy while trimming.

I like to trim nails when chickens are roosting at night while wearing an inexpensive headlamp and a partner to hold the bird. Grasping the foot firmly in one hand, trim off one-fourth to one-third of the length of the nail. If the nail bleeds, immediately dip it in styptic powder and hold gentle pressure on it with a paper towel until the bleeding stops. File any sharp or jagged edges.

Spurs are hornlike, bony projections that grow out of the back of a rooster’s lower leg and are used for personal defense and flock protection. Think of the spur like a thumb that’s completely covered by a thick, sharp fingernail. A rooster’s spurs continue to grow just as his nails do and, if left unchecked, can interfere with his ability to walk, causing injury to him and others. Blunted spurs after trimming are safer for everyone. Even some hens can grow spurs, so don’t be surprised to find one of your older hens in need of a spur trim too!

Certain breeds, such as Dorkings and Silkies like Freida (above), have extra toes growing in odd directions, which makes it impossible for the birds to maintain their length. In such cases, nails will require periodic trimming.

Spurs are bony, horn-like projections used for personal defense and flock protection.

To maintain a reasonable length, the spur cap can be trimmed or removed, a process known as uncapping. I do not uncap my roosters’ spurs because when the hard outer layer of the spur is removed, the exposed bony tissue may bleed, is painful when touched, and is vulnerable to infection. It’s not unlike ripping a nail off your own finger. I just can’t get on board with the procedure.

The same method for trimming nails applies to spurs: steer clear of the live tissue underneath the spur cap, conservatively cut only the first one-fourth to one-third of the projection with very sharp, large dog clippers, and file any sharp edges. The spur caps will regrow.

Preparing for Illness and Injury

Most of us spend a great deal of time preparing for the arrival of our first chickens, but few of us give much thought to how we will handle serious illnesses or injuries. Nothing leaves a chicken keeper feeling more powerless than not knowing how to help a flock member in need, but being prepared can make an already-difficult time less stressful. Plan an infirmary space before it is needed and keep first aid supplies on hand.

INFIRMARY SPACE

A chicken infirmary space should be conveniently located in a warm, quiet, predator-proof area away from the flock that allows frequent observation of the patient. A small rabbit hutch or collapsible dog kennel works well, allows excellent visibility, and can accommodate areas for food and water. It should be lined with litter such as pine shavings or soft towels, be large enough for the chicken to stand up and turn around in, and have an area where the chicken can relieve itself away from its food and water.

Plan for a chicken infirmary—a space located in a warm, quiet, predator-proof area away from the flock. Petey is an Araucana pullet.

FIRST AID KIT

In addition to an infirmary space, you should keep a chicken first aid kit handy. A plastic container with a lid works perfectly well to hold the supplies. Do not keep first aid supplies inside the chicken coop—temperature extremes will degrade and reduce the effectiveness of many products. Here are the items you should have:

• Vitamins and electrolytes (for shock and dehydration)

• Eye dropper or syringe (for hand-feeding water, medications, and liquid nutrition)

• Powdered baby bird formula (for hand-feeding)

• Epsom salts (for soaking some injuries)

• Nonstick gauze pads

• VetRap self-sticking bandages (for spraddle leg and wrapping wounds)

• Disposable gloves

• Tweezers

• Dog nail clippers (for trimming beaks, spurs, and toenails)

• Styptic powder (for bleeding nails and beaks)

• Antibiotic ointment

• Superglue (for broken beak repair)

• LED headlamp or flashlight

• Vetericyn Poultry Care Spray (for wounds)

• Aspirin (not baby aspirin)

• Chicken saddle (for hens with feather loss from overmating)

• ProZyme powder (digestive and nutritional support for ill chickens; sprinkle 1/4 teaspoon onto 1 cup of feed)

• Old towels (for calming a chicken during a procedure and bedding for very sick birds)

• Phone numbers of veterinarian and state’s animal pathology lab

Do not keep first aid supplies inside the chicken coop—temperature extremes will degrade and reduce the effectiveness of many products.