When Major General MacAndrew left Damascus with the 5th Cavalry Division with Aleppo as his objective it was known that he had a pretty tough proposition in hand. Aleppo was a Turkish Military depot where several divisions were stationed with large supply and ammunition reserves. It was also a railway depot and junction of the two railway systems to Bagdad and Damascus and was in direct communication with Constantinople.

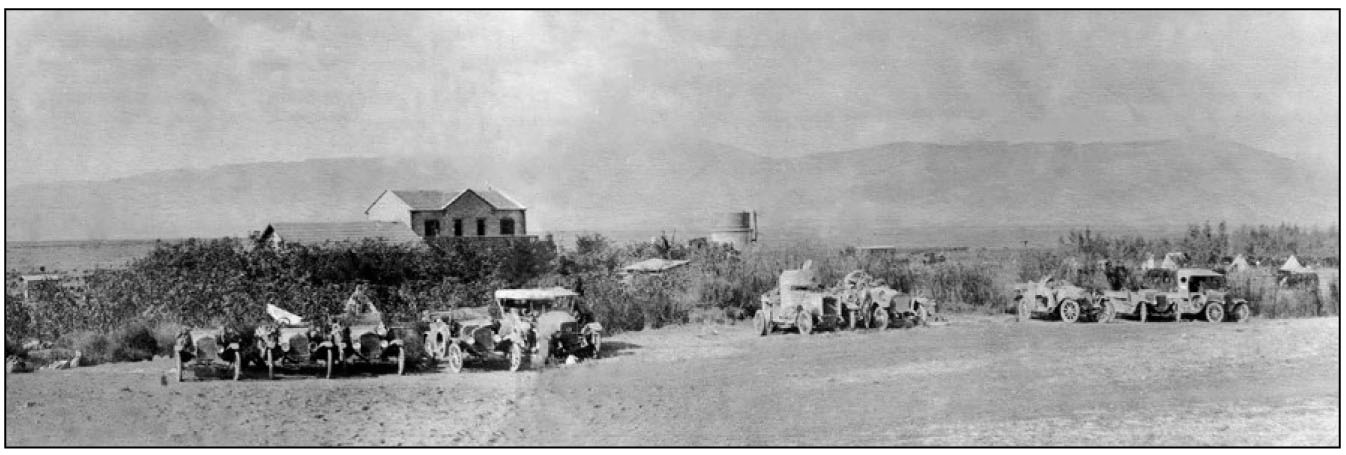

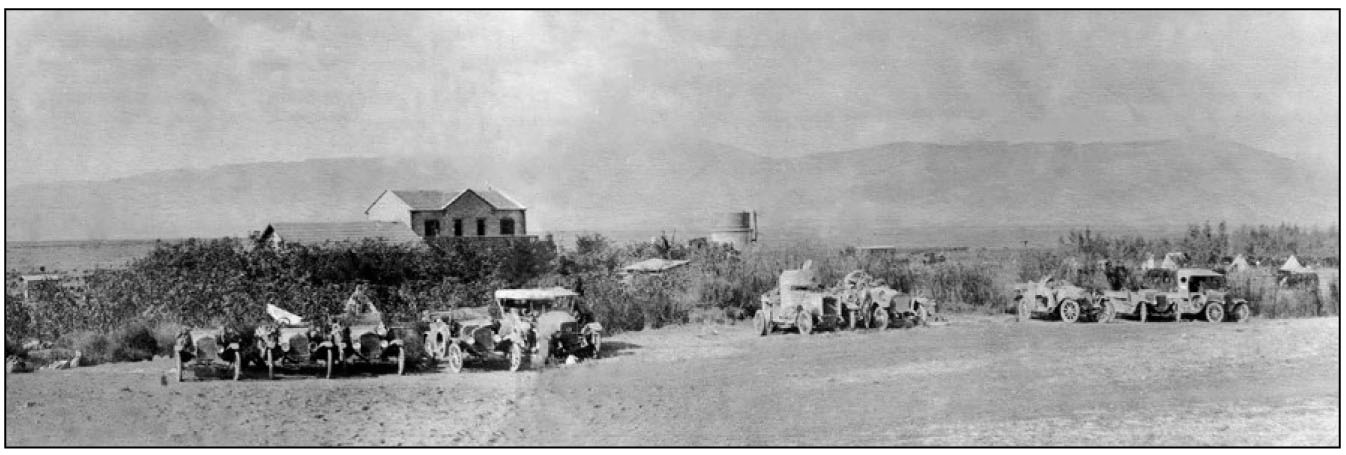

50. The vehicle park of the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol and the British Armoured Car Batteries in Syria, 1918 (ATM LCP 006).

On the other hand the 5th Division was only about half strength on account of the losses through disease and battle etc. The horses were more or less done on account of the strenuous operations preceding the taking of Damascus and there was over 200 miles to go before reaching the objective with perhaps the prospect of strong enemy resistance anywhere on the route. Nevertheless, the division made excellent progress considering the conditions for over a third of the distance when it was realised that progress was getting considerably slower and the horses were becoming more or less done.

General MacAndrew or “Fighting Mac” as he was known, realised that something else would have to be done if the operations were to be successful as speed was one of the main factors necessary for success. The General then decided when the division reached Homs to collect all the available motors together and make a rush for the enemy’s base leaving the division to follow on as soon as possible. Three Armoured Car Batteries (Nos. 2, 11 and 12 Light Armoured Motor Batteries) and three Light Car Patrols (Nos. 1, 2 and 7 Light Car Patrol) hastily collected together their necessary transport vehicles. Each armoured car battery consisted of four 50 hp Rolls Royce armoured cars, each mounted with a Vickers machine-gun and each Light Car Patrol consisted of four light cars each mounted with a Lewis gun. Both units of course had necessary tenders accompanying them with extra petrol, oil, water, rations and ammunition. Thus the fleet mounted between them twenty-four machine-guns with their crews and transport. The armoured cars were the battleships of the fleet, but owing to their weight they were more or less compelled to stick to the hard ground. The cars of the Light Car Patrols, while they did not have the protection of the larger vehicles, could venture on to places where the others could not go and were like the light cruisers of the fleet.

This little mobile army with General MacAndrew in command himself left Hama at daybreak on the morning of the 22nd of October 1918 and said goodbye to the rest of the division.

After driving due north for an hour or two a fleet of enemy motor vehicles hove into view; these vehicles consisted of a German armoured car and a number of German motor lorries fitted with steel tyres and each mounting a machine-gun and then began one of the prettiest little fights that has probably ever been witnessed. This was probably the first occasion on record of a battle between two fleets of motor vehicles. The German vehicles saw that they were outnumbered and were making all haste to get away north firing frantically with their machine-guns from the rear of the lorries as they bounced and jolted over the rough ground. The big German armoured car endeavoured to cover the retreat of the other vehicles. Our armoured cars rushed up alongside the enemy vehicles and a running fight ensued at a speed of about thirty miles per hour with the Light Car Patrols hovering round to get a shot in now and then, while some of them rushed ahead in order to cut off the enemy vehicles. The shooting from the German lorries was very erratic, as owing to the roughness of the ground, the speed at which they were travelling, the gunners one minute would be firing into the ground and the next into the clouds. After a few minutes of this running fight the German armoured car suddenly stopped, a door opened at the side and the crew rushed out towards some barley crops growing alongside the track only to be shot down as they ran. The other lorries were then gradually surrounded and captured and some caught fire and were burnt. On examining the enemy armoured car we found that the engine was still running and we soon discovered why the crew left it so hurriedly. The fact being that it was a very unhealthy place to be as the bullets from our vehicles were penetrating the supposed armour plating and going clean through both sides at close range. The bullets from the German cars only fell harmlessly from the plating of our armoured cars, so the fight was more or less a one sided one. After this little delay the column pushed on once more and by evening we had reached the village of Seraikin where it was decided to stay for the night. Outposts and machine-guns were placed around the camp and everyone took their turns at watching through the night. The village of Seraikin contained an aeroplane depot and we surprised the occupants in time to prevent any planes from rising.

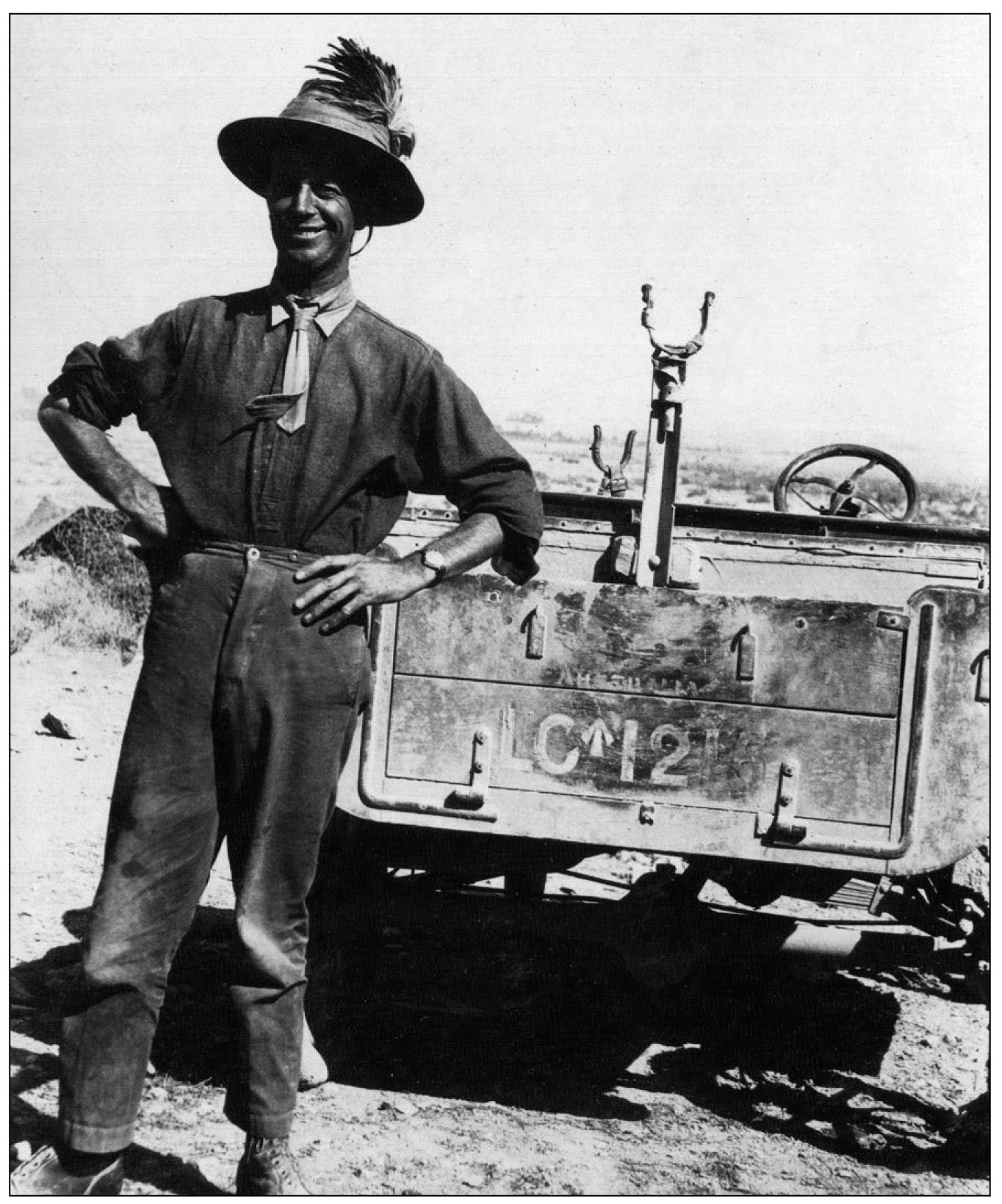

51. A smiling Captain James in typical officer’s working dress, complete with necktie and a Light Horse emu plume in his slouch hat. The car, LC-1216, was one of the new cars taken on strength in December 1917. Note the two u-shaped mounts for the Lewis light machine-gun, and the pedestal-type mount in the rear of the vehicle to provide elevation for firing at aircraft. The insignia ‘Australia’ has been stencilled above the registration number (Cornwell collection ATM LCP.PC.013).

When we arrived at Seraikin we were fortunate in being quick enough to prevent the aeroplanes there from taking off and flying to Aleppo with the information of our proximity. We were especially anxious that the enemy should not know what a comparatively insignificant force was advancing against them. The General wished to use the element of surprise to gain as much advantage as possible. Near the village we discovered a small gun with a calibre of about 1.5 inches. It was mounted on a small folding carriage something like the German Maxim gun tripod. There was also a case of shells. These were something after the style of the Pom Poms and would be under one pound in weight. We put the lot into the back of one of the cars and they came in very useful later on. Next morning we made an early start as usual and proceeded north until we came to Khan Tuman. Here the cars suddenly and unexpectedly ran into a small detachment of Turkish Cavalry. There was a sudden burst of fire from the Lewis Guns and a couple of the Cavalrymen fell wounded. Some of the Light Cars then made a rush to head off the horsemen from the direction of Aleppo, which they succeeded in doing. The officer in charge and a party of his men were surrounded and they surrendered. A few of the remainder galloped off to the west where they got into some rough timbered country where the motors could not penetrate without a lot of trouble. As they were cut off from Aleppo it did not matter very much what happened to them. After this little episode the force pushed on again and was almost in sight of Aleppo before any serious opposition was encountered.

The flying motor force had been particularly fortunate. First of all the enemy motor vehicles had been encountered and exterminated. Next the aeroplanes had been caught before they had time to rise and then the cavalry patrol had been cut off. So the enemy headquarters had practically received no news whatever of what was happening and the surprise was complete. They were evidently very anxious thinking that something was wrong and were nervous. However, on reaching a position within view of town it could be seen that the place was alive with troops. Trenches had been dug all round the city and the troops could be seen in these through the field glasses. A couple of armoured cars drove down the road towards the city and encountered a storm of rifle and machine-gun fire. Some batteries of artillery also opened up with shrapnel High Explosive. The General then called a halt and collected his small force under shelter of a friendly hill for a council of war. He then decided to make as much display of force as possible. The armoured cars manoeuvred on the skyline making as much display and dust as possible. Some of the Lewis guns were taken off the light cars, which were also driven about in view. The guns were carried along under cover of some stonewalls and rocks so as to get within range of the trenches and make as much noise as possible. In the meantime, our “brave” allies the Arabs apparently began to think something was doing and could smell loot for they began to collect in thousands on the horizon in every direction. In the distance it looked like an army collecting on the doomed city.

Several hundred of these Arabs mounted on horseback collected in the rear of our cars and one of them who was apparently a man of importance after talking with our interpreter began to harangue his followers with the result that they all sprang into the saddle and rode forward up to the motor car column. Apparently this was not enough for their leader for he began to talk and yell at them seriously for about ten minutes or a quarter of an hour which presumably had the effect desired as they all rode forward onto the skyline. Immediately about ten machine-guns and a couple of batteries of artillery opened fire. That was enough. The horsemen all turned tail and galloped until they were out of sight to the yells and jeers of the British and Australian onlookers. It was now our turn to make some show and several parties of machine-gunners crept forward with their Lewis guns. We also carried along our captured Pom Pom and sent across all the little shells from various positions at extreme range. Although they did no damage they made plenty of smoke and noise, which is what we wanted, for it looked to the Turks that we were bringing artillery up. After this the General decided on a bold stroke and resolved to send a demand to the Turkish Commander in Chief to surrender. Accordingly in the afternoon Lieutenant McIntyre of No.7 Light Car Patrol drove into the enemy’s lines in a car under a white flag with documents for the Turkish Commander. No shots were fired at the car, but when the Turkish trenches were reached the car was stopped. McIntyre was blindfolded and taken through on foot to an officer who took him to the Turkish Commander who was very courteous. General MacAndrew’s ultimatum requested the immediate surrender of all troops, arms and materiel in the town. In return the General promised safe custody and the best treatment given to prisoners of war.

There was no sign of the car with the white flag returning and it was decided that McIntyre must have been taken prisoner but after about four hours’ absence, he returned with a reply.

This was to the effect that the Turkish Commandant of the town could not reply to the demand, as he would have to communicate with Constantinople for instructions. However, the reply showed weakness. We found out afterwards that the Turks’ chief fear was of the hordes of Arabs hovering around, as these gentry were always ready to fall on the defeated side and cut the throats of as many as possible. The Turks were very nervous about these fellows and although we found them useless as fighters they were indirectly of use on account of their reputation. That evening as we stood on the hills watching the city fires began to break out everywhere, explosions occurred in the city and railway stations and yards. Then we knew that the bluff had worked and the Turks were preparing to evacuate. We could see railway trains leaving the other side of the town. The sky was lit up over the town all night. Next morning we drove into the city without opposition and as the last train drove out of the town with Turkish troops on one side the Armoured Cars and Light Car Patrol drove in along the road on the other side to the accompaniment of cheers and the usual banging of rifles of the inhabitants. As we drove into the town an enterprising moving picture operator took views of the column entering and a few days afterwards we saw views of the entry of the town in the local cinema theatre.

A peculiar feature about the operations of the day before during the manoeuvring of the cars outside the town was the fact that although the enemy batteries shelled us heavily and although nearly everyone in the Light Car Patrols received a pellet of some description, nobody was hurt. Some of the bullets seemed to have no penetrating power and did not even penetrate the uniforms. Lieutenant Cornwell picked a pellet out of his Sam Brown belt that would have gone through the region of the heart if it had only had enough power. Numbers of splinters and pellets next day were dug out of the woodwork on the cars while one driver got one on the knuckles of his hand when driving, making him momentarily release the steering wheel with a yell but beyond a slight cut his hand was uninjured. We came to the conclusion afterwards that the shrapnel must have been stuff that been kept for many years and had lost its power, fortunately for us.

However, Aleppo was the Grand Finale of the best stunt we had had. By this time the advance men of the Mounted Division were well on our heels and we soon had a strong force in the town, although nothing like the number of troops that had just left it. For the first couple of days we had to quieten the Arab and Bedouin looters who started to rob all the inhabitants of the town as soon as the Turks withdrew but we soon had these fellows under control.

The capture of Aleppo took place on the 26th October. The Turks withdrew to the north-west and established a line of trenches about 15 miles out. The division followed and took up positions outside the town across the road to Alexandretta, the Armoured Car Batteries and Light Car Patrols taking up their share of this work.

The armoured cars attempted a reconnaissance a few days afterwards to test the Turkish defences. They found that the enemy had blown up all the culverts and bridges along the road and had dug trenches and pits at narrow crossings to make it difficult for vehicles to traverse. They got well shelled all along the road and found that the enemy was in strength and after about an hour of this they returned to camp intending to try other routes later on but on the 31st October at noon an Armistice was declared with Turkey and all fighting was off.