CHAPTER FIVE

The first Portuguese voyage to India in 1497–1498, and its sequel in the Indian Ocean, is such a compelling piece of history that it has overshadowed the history of Portugal, Africa, and Brazil. The less dramatic story of the South Atlantic starts in the same place as the opening of the Indian Ocean: Lisbon, Genoa, and the ports near the Strait of Gibraltar. The focus shifts when we look at the coastal islands of Africa and the gradual buildup of trade based on sugar and slaves. It begins with the settlement of the Cape Verde Islands and the island of São Tomé. São Tomé developed a prosperous sugar industry based on free land (the island was initially uninhabited), European capital, and African slave labor. As the sixteenth century progressed, these islands were well located to become entrepôts in the trade between West Africa and Brazil, especially as intermediaries in the trans-Atlantic African slave trade. Initially the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé traded between the west coast of Africa and Brazil, and then between Africa, Brazil, the Caribbean, and Europe.

Sub-Saharan Africa and its Atlantic coasts are probably the victims of more stereotypes than any other part of the world. The image of jungle tribesmen with stone-age weapons propagated by the Tarzan movies is seriously misleading. The area south of Algeria, Libya, and the Sahara was a broad, grassy plain that became tropical forest as you traveled farther south. From Roman times this region was the home of a sequence of empires with large armies, effective cavalry, and important centers of Muslim learning. The western part of this sub-Saharan region contained three major gold-mining areas. Since there was a strong demand for gold in the Mediterranean world, the mines were the basis for a substantial trans-Saharan caravan trade, and several routes crossed the desert between Jenne (Djenné), Timbuktu, Gao, and North African ports. The merchants who arrived along the Saharan trade routes were usually Muslim, and as in many places, the Muslim merchants soon converted local elites to Islam.1

The revenue from this trade helped support large royal courts and armies. Between the early thirteenth century and the fifteenth century, the Mali Empire was the dominant power in West Africa, but it seems to have reached its peak about 1330. At that time, it controlled the coast between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers and stretched inland for more than a thousand miles. The Portuguese wanted to reach the Mali Empire because it was the legendary source of African gold. In the fifteenth century, when the Portuguese finally made direct contact with the Mali Empire, it had been greatly reduced by invading Songhai warriors. The Songhai Empire (1375–1591), created by this aggressive warrior elite, took control of most of Mali’s territory and eventually became one of Africa’s more important exporters of slaves.

As the Portuguese discovered, African society had both the organization and the technology it needed to resist European incursions. West Africans were familiar with horses and used them effectively for cavalry. They knew how to work copper, brass, bronze, and iron. Their weapons (knives, swords, spears) were of iron, and they quickly learned how to use guns. A well-trained African army, complete with cavalry, was a formidable opponent; larger kingdoms could field armies of several thousand infantry and large troops of cavalry. Africans also knew how to cast metal into everyday utensils and decorative objects. They were skilled blacksmiths, and in colonial Brazil, a slave who had been a blacksmith in his West African home was a valuable asset on any plantation.

By 1500 the ruling elites of sub-Saharan Africa were nominally Muslim, but many of them also acknowledged the animist cults practiced by most of their subjects. Sub-Saharan Africa had centuries of experience with trade and cultural exchange, and cities like Jenne and Timbuktu were major seats of Muslim learning.2 On the fringe of this economic region, the West African coast was controlled by a variety of polities, large and small, many of which maintained their political independence from Europe until the nineteenth century.

Although many of the states of coastal Africa were small, the Portuguese learned not to try to occupy them or overawe them with military force. While Native Americans were vulnerable to European diseases, the situation was reversed in Africa and the tropics. Disease was Africa’s first line of defense and included sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis), bilharzia (schistosomiasis), malaria, and yellow fever—diseases to which Europeans had little resistance. Early modern European armies exposed to mosquitoes, tsetse flies, or water contaminated with schistosomiasis parasites, compounded by their minimal sanitation practices, were quickly decimated by disease.3 The Portuguese learned to avoid land campaigns in coastal Africa and instead negotiated with local rulers. They seem to have forgotten this experience in the late sixteenth century when they sent hundreds of Portuguese troops into inland campaigns in Angola, where most of them soon died or deserted.

The Portuguese traded with the Songhai, who traded slaves for horses, guns, gunpowder, and other iron weapons, which they used to threaten neighboring countries and mount additional slave collecting expeditions. Benin was another important West African state, and one with which the Portuguese had many interactions. Benin took shape in the mid-fifteenth century, occupying the area between Dahomey and the Niger delta and between the coast and the Yoruba Kingdom. It was ruled by a series of effective kings. With a strong, well-trained army and coastal navy, Benin dealt with the Portuguese as equals and remained independent well into the nineteenth century.

The political scene in West Africa between 1450 and 1750 saw two more strong states emerge in the area of modern Nigeria: the Yoruba Kingdom of Oyo and Dahomey. The Yoruba Kingdom of Oyo took shape in the second half of the sixteenth century; with a strong army and an effective cavalry, it lasted some two hundred years. During that time, it was effectively the middleman for trade between the inland societies to the north and the coastal kingdoms to the south. It has been suggested that part of the reason for Oyo’s success was the availability of European horses and weapons, which gave it a military advantage over countries farther inland. Dahomey took shape beginning around 1600 and gained control of two of the major slave trading ports, Whydah and Allada in modern Benin. By the 1700s, Dahomey was one of the most important slave trading countries, supplying thousands of slaves not only to the Portuguese but also to Dutch, English, and French slavers. Like Oyo, Dahomey maintained its importance in part because the European merchants were happy to trade guns for slaves.

Along much of Africa’s west coast, in addition to the Kingdom of Benin, the maps of sixteenth-century West Africa include numerous small and mid-size kingdoms. Some regions housed very small polities that controlled only the land identified with one or two extended clans, within which certain families were by tradition the heads of state.4 It is important to note that most of these states, even quite small ones, retained their autonomy in their interactions with Europeans. They were reluctant to allow permanent settlers, or lanzados, to settle permanently in their territories, and lanzados were more likely to be found in the small “stateless” societies.

Farther south, in the very different environment of the forest zone, was the Kingdom of Kongo, perhaps the African state that has gotten the most attention from historians. Located in the northwest corner of the modern country of Angola, Kongo was first consolidated about 1385. By the time the Portuguese arrived in 1483, it had also taken over the Kingdom of Loango on its northern border, in what is now the Republic of the Congo, and claimed the Kingdom of Ndongo to the south as a dependency. With a well-defined tax structure, an effective army, and recognizably monarchical royal protocol, the Kingdom of Kongo was a state worthy of respect.

The Portuguese who first visited the African coast in the 1400s were as inclined to raid the isolated villages as to try to trade with them. This was their first step in a century of learning how to relate to African societies and their ruling elites. Meanwhile, the Genoese, Catalans, and Portuguese in the Mediterranean were trading with medieval North Africa—a perennial source of gold that had been brought to the coast by trans-Sahara trade caravans since the fourteenth century. The Genoese visited North African ports and knew quite a bit about this trade with sub-Saharan Africa.5 As early as the 1350s, European expeditions, some with Genoese backing, had ventured down the African coast as far as the Gambia delta and the Canary Islands.

Various small expeditions tried to trade with the Guanches who inhabited the Canaries; a few missionaries even tried to convert them to Christianity. Their reports were so optimistic that the pope even established a bishopric for the Canary Islands. Castile’s first official attempt to conquer the Canaries took place in 1402–1406, but the last of the islands was not conquered until 1495.6 While Castile concentrated on the Canary Islands, the Portuguese focused on the African coast. They captured the Moroccan ports of Ceuta (1415) and Alcazer (1458). In 1443 the Portuguese found and fortified the island of Arguim (Arguin), off the coast of Mauritania. Arguim then became a base for trade with the nearby African coast allowing the Portuguese to establish a connection with the inland caravan town of Wada and divert some of the caravan trade to the coast.7

As the Portuguese moved south along the coast of Morocco and Mauritania, they used a combination of raiding and trading that was only marginally profitable. Their main revenues seem to have come from the sale of a small number of African captives. Moving farther into the delta areas of the Gambia and Senegal Rivers, the Portuguese discovered countries well able to resist their armed attacks, and got a rude surprise when they raided part of the Wolof Kingdom. The Wolof soldiers and war canoes made short work of the Portuguese soldiers and captured any ships the Portuguese brought into the inshore waterways. The Portuguese also discovered that West Africans were familiar with long-distance trade and had learned Mediterranean business techniques from Arab, Armenian, and other merchants that had been trading across sub-Saharan Africa.8

By the 1460s, the Portuguese had developed a thriving trade with the kingdoms in the Senegal-Gambia area and finally reached the Mali Empire and its gold mines by traveling up the Senegal River far enough to make contact with Mali. Mali and other states exported gold, bronze castings, cloth, malagueta pepper, and slaves in return for European cloth, iron ingots, and horses. Some trans-Sahara caravans were attracted to Portuguese outposts on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, where their cargoes were loaded onto Portuguese ships bound for Lisbon. Within a generation of first contact, the trade in Senegal-Gambia was brokered by mixed-race Luso-African merchants and brokers, men and women who were the descendants of the first white settlers and their African wives. The Mali gold had been one of the explorers’ early objectives, and by 1500 a modest but varied trade had been established with the northern coast of West Africa, trade in which the Portuguese diverted a substantial amount of the trans-Sahara gold trade to Lisbon.9 As African coastal towns became active seaports, inland trade diasporas were drawn to the new markets along the coast.

Possibly the most powerful and effective state along the African coast was the Kingdom of Benin. The oba of Benin was willing to keep up diplomatic ties with the Portuguese, but he refused to convert to Christianity and did not allow the Portuguese to introduce missionaries. He requested European firearms, but when the Portuguese refused, he restricted the Portuguese to a narrow range of foreign trade goods that included pepper, ivory, and cotton cloth. Benin also resisted the introduction of large-scale slave trading, limiting it to a level that met its domestic needs. As a result, Benin retained its own identity and autonomy until the nineteenth century.

The most distinctive of the assorted relationships that defined Portugal’s role in Atlantic Africa was its association with the royal family of Kongo. The Portuguese first visited Kongo in 1485 and recognized it as a well-run and well-defended country. They opened diplomatic relations with the royal family in 1490, establishing a close relationship that lasted until the 1560s. By 1491 they had succeeded in converting the king to Christianity. The Portuguese supported the royal family against domestic opposition and worked with the royal family to promote Christianity. In return, the king granted the Portuguese carefully limited slave trading privileges, including a prohibition on enslaving Kongolese subjects.

While the king and the Portuguese negotiators agreed on limiting aspects of the slave trade, Kongolese nobles with access to seaports made deals with slave traders from São Tomé and the Cape Verde Islands. They enslaved any Africans they encountered whether they were Kongolese subjects or not. The effect was to erode the authority of the king while making Kongo one of the biggest exporters of slaves in Africa.10 This progressively undermined the Kongolese monarchy.

The Portuguese had avoided territorial conquest, which involved sending troops into Africa, because of the high mortality among troops in the field in the tropics. They changed their policy at the end of the 1500s and mounted overland campaigns in Kongo and Angola, in part because of diplomatic commitments to the Kongolese monarchy, which on various occasions sent Kongolese troops to support Portuguese interests. This arrangement was interrupted in the late 1560s when a people called the Jaga overran Kongo and forced the king into exile. The Portuguese, possibly hoping to emulate the Spanish takeover of the Aztec Empire, then mounted a military expedition to restore the deposed king.

Six hundred Portuguese soldiers, supported by large contingents of Kongolese soldiers, successfully restored the king, but the outcome was anticlimactic. Rather than staging a coup at the top, as in Mexico and Peru, the successful Portuguese army simply melted away. Virtually all the European recruits either died or became lanzados, married African wives, became traders or ranchers, and merged into Kongolese society.

Recognizing that the Portuguese had used their own soldiers to support his government, the Kongolese king in turn provided soldiers for a Portuguese campaign in the Kingdom of Ndongo to the south, the logical first step toward a conquest of Angola.11 The official reason for the invasion was an attempt to establish a colony of Portuguese settlers in Angola and gain control of “unused” land suitable for planting Portuguese colonies. The real reason was the slave trade. The Kingdom of Kongo had maintained a regulated segment of the slave trade, but after the Jaga invasion, the slave trade had become something of a free-for-all. Meanwhile, conflict between Kongo and Ndongo led to a Portuguese attack on Ndongo with Kongolese help. For the first time, the Portuguese used their own troops to round up and enslave Africans in Angola. This was an exceptional act, since everywhere else in Africa the slave trade depended on African forces to round up the prospective slaves and on African brokers to bring slaves to the seaports for delivery to European buyers.12

After the restoration in the early 1560s, the political base of the Kongolese monarchy was weak and fragile. The informal slave traders from Portuguese-controlled São Tomé began trading with Kongolese regional nobles, who ignored royal authority and raided parts of Kongo itself for slaves. Confronted by internal dissent, slave raiding by independent lanzado merchants, and Portuguese slave raiding in Angola, the political base of the Kongolese monarchy disintegrated.

The years 1427–1433 saw the discovery and colonization of the Azores. The Cape Verde Islands were discovered in 1456; São Tomé, near the mouth of the Congo River, was discovered in 1473. Without the story of the Atlantic islands, any account of the opening of trade with Africa or Brazil is incomplete. These islands were strategically and economically important.

The role of the Azores was different from that of the coastal islands. Despite their apparent isolation, nine hundred miles out in the Atlantic, the Azores were ideally located for the return to Lisbon from West Africa. Prevailing winds and currents favored the trip south along the African coast, but the return was very difficult until navigators learned to sail northwest from Africa, cutting across the prevailing winds until they reached forty degrees north latitude, where they found the prevailing west-to-east winds that took them directly to Lisbon. By happy coincidence, the Azores were located at that latitude and provided a well-placed resupply port.

Beginning in 1492 with Columbus’s first voyage, the Canary Islands were strategically valuable because they extended far into the Atlantic and were useful as a place to pick up the equatorial trade winds that blew toward America. In 1479 the Portuguese recognized Castile’s title to the Canaries—just in time for them to become a crucial link in Spanish communications with America.

Farther south, the Cape Verde Islands played a key role in the history of Portugal’s relationship with both Africa and Brazil. With erratic rainfall and an unpromising climate, the Cape Verde Islands attracted only a few white Portuguese men as settlers. To spur development, in 1462 the king of Portugal granted captaincies in the Cape Verde Islands to several petitioners who wanted to develop plantations in the new colony. A captaincy was both an administrative post representing the king and a hereditary fief. The captains, in turn, imported African slaves to help develop the islands. As in other colonies, the European settlers married African women, and the islands soon had a Luso-African elite that no longer identified with Portugal, along with a much larger population of both free and enslaved Africans. The islands’ location proved convenient as a base for further African coastal exploration and, after 1497, as a resupply port for ships bound for Brazil and India. The islands were too inhospitable to attract many European settlers, and only two of the islands had permanent settlements by 1500.13

Because they lived a short distance from the African mainland, Cape Verde residents were inclined to ignore trade regulations made in Lisbon and developed their own commercial relationships with the mainland. Since the climate was too erratic for large-scale sugar production, Cape Verde Islanders gradually created a mixed agricultural economy that produced cotton and later cotton cloth for the African market.14 By expanding trade in those commodities and developing commercial contacts, Cape Verde Islanders became major intermediaries in the trade between Africa, Brazil, and later the Caribbean, often in violation of Portuguese policies. By the early sixteenth century, the Cape Verde Islands were also becoming a center for the collection and sale of American-bound slaves from the mainland.

By 1490 the Portuguese had also colonized the offshore islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. Located near the mouth of the Congo River, São Tomé’s merchants came to play a major role in Portugal’s trans-Atlantic network and were important in undermining Portugal’s relationship with the Kingdom of Kongo.

Both the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé were first settled under the auspices of the Portuguese Crown, but as in the Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé attracted only a few European men, who soon married African wives. Both colonies evolved into virtually independent societies, with commercial activities that ignored policy from Lisbon. In both cases, while the initial settlers included men recruited from Portugal, before long most of the nominally Portuguese residents were mixed-race lanzados. Found all over the Portuguese sphere of influence, these often mixed-race lanzados were men who left European jurisdiction and moved to the fringes of the Portuguese world. Wherever they settled, they adopted local religion, clothing, and eating habits. Some of them abandoned all traces of European culture and blended into the society around them. On the Portuguese-controlled Atlantic islands, after two or three generations of racial intermarriage, it was impossible to distinguish between a self-defined European and an African, suggesting that the European, in this case Portuguese, identity was very weak. Clearly, skin color and race were less important in these colonial societies than were class, status, and business connections, especially in places where European immigrants were few, and almost entirely men.

Unlike the Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé was also an ideal place to grow sugar. Since it was uninhabited when the Portuguese discovered it, the island’s few European settlers began planting sugar and importing African slaves to work in the cane fields. By 1500 the island was a major exporter of sugar; later in the sixteenth century, when Brazil also became a producer of sugar, São Tomé became an important intermediary in the slave trade, sending African slaves to the sugar plantations of Brazil. The people of both the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé were also adept freelance traders. They built their own small boats, traded at many different places along the African coast, and avoided or ignored Portuguese attempts to regulate or tax their trade.15

In the early sixteenth century, Portugal’s place in Atlantic Africa was framed by three disparate economic elements. The crown controlled the long-standing gold trade from Mali and Songhai. It also profited from its royal slave-trading activity in the Kingdom of Kongo. As this implies, gold and slaves were the king of Portugal’s two most important sources of African revenue; gold alone covered as much as 25 percent of the royal budget. Portuguese Africa also depended on a less tangible asset: the growing network of independent traders and merchants who avoided royal authority. They could be found in almost any seaport on the African coast, in addition to the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé. During the sixteenth century these independent merchants played an increasingly important role in the third economic development, the slave trade. Portugal’s loose-jointed sphere of influence over Atlantic Africa was held together by those three elements and a maze of treaties, subsidized rulers, trade outposts, and diplomatic understandings that varied from one African kingdom to another.

Portuguese involvement in the coastal kingdoms varied. In the kingdoms where Portuguese lanzados were allowed to settle, their social development was similar to that of the lanzados on the islands, and a growing number of Portuguese men became permanent African residents or even citizens. Mainland lanzados learned the local language, married African women from important commercial or political families, and converted to the local animist religion. Their Luso-African children grew up with backgrounds in both cultures and often became powerful as brokers and intermediaries between local African society and the Europeans.16

During the sixteenth century, Portuguese commercial activities shifted south from the Senegal-Gambia to El Mina, Benin, São Tomé, and Kongo. One stream of trade was sponsored by the Crown and went to certain regulated ports. There, as in Kongo, representatives of the Portuguese crown were backed by the local government. Elsewhere, a second stream of commerce was carried on by independent merchants living on the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé. They carried a growing share of African trade and traded when and where they pleased, ignoring government controls. These merchants were ideally positioned to exploit the expanding maritime connections with Brazil.17

While Portugal was building its sphere of influence in Atlantic Africa, its leaders were also pursuing the possibility of sailing around Africa in order to get to Asia. Bartolomeu Dias had found the Cape of Good Hope and verified that he really was in the Indian Ocean in 1488. This set the stage for the first trip to India, a trip that was also a daring experiment.

Knowing that the winds and currents on the coast of southern Africa were against him, and knowing that his ships could not tack effectively into the wind, Vasco da Gama was determined to find a better route to southern Africa and Asia. The gamble began when he sailed southwest from the Cape Verde Islands, almost directly away from Africa. By following the tropical trade winds that blew southwest across the southern Atlantic, da Gama was gambling that he would find prevailing winds from west to east near latitude forty degrees south. No one had actually seen those winds, but da Gama assumed that since similar winds crossed the North Atlantic, he would find them in the South Atlantic. His gamble paid off, and he was able to make a giant loop that took him back to the southern tip of Africa. In doing so, he not only set the route to Asia for the next four hundred years but also marked the beginning of Portugal’s Asian “Empire.” He did not, however, sail west far enough to find Brazil.

The story of Brazil began in 1500, when Pedro Álvares Cabral led Portugal’s second India fleet southwest from the Cape Verde Islands. Cabral held that course longer than da Gama had, with the result that he encountered the coast of Brazil. In Brazil, as elsewhere, first encounters were almost always warily cordial. Indians generally met strangers with gestures of peace and hospitality. Having discovered Brazil on his way to India, Cabral went through the ritual of claiming what he thought was an island for the king of Portugal. He stayed nine days before continuing on his way to India.

Brazil had no recognizable rulers or governments with which the Portuguese could negotiate, and appeared to have little to offer that was worth the trouble of carrying it back to Europe. Preoccupied with the spice trade, the Portuguese Crown ignored Brazil except as a supply stop for ships on the way to India. Thus no one paid much attention to this new discovery other than a few solitary lanzados, who settled among the Native Americans.

The first commercially viable Brazilian export was brazilwood. Brazilwood was used to make a high-quality, deep red-brown dye for expensive woolen cloth. By the 1520s a few lanzados, using Native American labor, were exporting significant amounts of raw brazilwood. Brazilwood trees, about two feet in diameter, were scattered throughout the forest, one or two trees per acre. The trees were felled, their bark was stripped off, and the trunk was cut into portable pieces of about seventy-five pounds. The wood was taken to the shore and stacked at coastal landing sites until a supply ship picked it up.

In the first decades a few men became lanzados, staying permanently and living among the Brazilian Indians. Only in the 1530s did the Portuguese Crown begin to promote settlement by granting hereditary captaincies to Portuguese noblemen and businessmen. Each grant included a stretch of coastline and reached well into the interior. The recipients were supposed to explore their property, search for valuable exports, and bring families from Portugal to create a permanent European presence. Only a few of these captaincies were actually settled, but the Brazilian coast acquired a number of small settlements.

Like many of the early European settlements in the Americas, the small colonial towns in Brazil were often unable to feed themselves. They survived with the help of local Indians who, responding to both coercion and negotiation, traded food for simple European goods. This marks a sharp contrast with Africa, where trade developed quickly as African countries imported European cloth, bar iron, and horses in return for gold, African-style cloth, and African pepper.

As they built permanent buildings, the newcomers persuaded the local Tupi and Guaraní Indians to work for them in the new settlements. As the first formal settlements took shape in the 1530s, the natives remained willing to trade but grew wary of being enslaved.18 The initial coastal settlements were soon populated by a motley assortment of people. The few Portuguese settlers were almost all male, ranging from voluntary settlers to refugees and exiled criminals. The rest of the population consisted of local Indians, a few African slaves, and some free Africans. Initial European interaction with the inhabitants of Brazil defies easy generalization.19 The Portuguese married Native American women, but when African women arrived with the Portuguese, the Portuguese also intermarried with them. The Portuguese seem to have preferred African or mulatto wives, possibly because they already spoke pidgin Portuguese or, having come from Kongo, were Christians.

The new towns, scattered along hundreds of miles of Brazilian coast, included São Salvador da Bahía, Rio de Janeiro, Recife, and Olinda. As late as 1550 the largest town, the new capital, São Salvador da Bahía, had only three thousand people. The little port towns of early sixteenth-century Brazil, with the forests behind them, faced the ocean and lived from their maritime connections. Since the interior offered no profitable exports, commerce in the Brazilian port towns amounted to little more than providing fresh supplies for the carracks outbound from Lisbon on the way to India.

Clearly, the results of early settlement were not overwhelming, but the volume of dyewood exports rose steadily. In 1548, as brazilwood exports rose, the Crown organized the scattered small settlements into a colony, with its capital and governor in São Salvador da Bahía. In the 1560s the Jesuits were allowed to establish several missions in a part of the interior that later became Paraguay. By the 1630s these missions had a large Indian population and owned thousands of head of livestock.

As in other parts of the world, the newly arrived Europeans examined the people they met for parallels between local and European society. In Brazil they found few signs of what Europeans defined as civilization. Civilized or not, one observer expressed great respect for the native way of life. Jean de Léry, a Protestant clergyman who came to Brazil in the 1550s with an unsuccessful French colony, spent several months living with the Tupinamba of Brazil. His memoir expresses admiration for the way native Brazilians treated their children and for their personal integrity.20 Initial contacts between European immigrants and native communities had a cautiously optimistic tone, but the unanticipated effects of European diseases soon colored every early encounter between Europeans and Native Americans.21

Many things shaped the long-term development of Brazil, but the most important early factors were the disastrous effect of European diseases on indigenous peoples and the need for cheap labor to produce any kind of profitable crop. Disease obviously came with the Europeans and would often appear within a few months of sustained European-American contact. Because of the small and scattered nature of Indian settlements, epidemics spread slowly; and their spread seemed inexplicable because neither Europeans nor Brazilians understood the process of transmission. Disease loaded the demographic dice in favor of the invading Europeans; by the end of the sixteenth century, Indian slavery and European diseases had left the coastal areas almost completely cleared of its original native population.

Seen from a larger frame of reference, Brazil’s early society exemplifies aspects of European expansion that were true almost everywhere. Whether the destination was Africa, Brazil, or India, almost all the Europeans who went abroad were men, and most of them were not likely to return. Brazil saw widespread ethnic intermarriage, both formal and informal. The Brazilian Indians had what Europeans considered relaxed ideas about sexual contact, and it was decades before the Brazilian settlements included a significant number of European women. Brazil’s commercial ties with Africa brought not only slaves but free African men and women. Consequently, intermarriage between European settlers and African or Indian women hardly merited comment. In fact, to a European exile living in a miserable, neglected Portuguese settlement, life in a Brazilian Indian community was sufficiently congenial to explain why colonists sometimes “went native,” echoing Jean de Léry’s respect for the native way of life.

Interracial marriages and liaisons were routine and, as the towns grew, gave children the cultural tools that allowed them to mediate between interior tribes and coastal settlements. Reflecting the matrilineal nature of Brazilian Indian society, native and mestiza women became the most effective cultural intermediaries in colonial Brazil. They emerged as recognized brokers and mediators known as mamelukas. This status allowed women to become overseers on slave plantations, where it was even customary for the mameluka to marry the owner of the plantation.

As in Southeast Asia or Africa, European fathers recognized their mixed-race children, had them baptized, and registered them as “Portuguese.” Mixed-race sons sometimes became mamelukos, a title that for a male implied not only the mediating skills of a mameluka but also a wider range of activities, including long-distance travel inland on behalf of the family business.22 Soon there were so many mestizo children approaching adulthood in Brazil that the Portuguese settlers, instead of asking for European women, petitioned the Crown to send more Portuguese men so that they could become husbands for their mestizo daughters. Whether formal or informal, extensive intermarriage reflected the lack of alternatives, but it also illustrates the flexibility of premodern, pre-Enlightenment attitudes toward color and race when compared with Europeans of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

From their beginnings, the small Brazilian port towns were part of a South Atlantic commercial zone. In 1548, when the Portuguese Crown gave the colony an official identity and a governor in Bahía, the first sugar plantations had already been established. By 1548 the sugar plantations in São Tomé and Príncipe were running out of good soil and planters were developing plantations on the coast of Brazil. The sugar industry expanded rapidly, and by 1600 Brazil was the world’s largest producer of sugar. Northern Brazil had a seemingly endless supply of good land, and for much of the 1500s, the plantation owners tried to solve their labor problems by capturing and enslaving Indians from the hinterland. This did not work well, since Indian slaves, exposed directly to European diseases, soon died or else escaped into the nearby forests. By the end of the sixteenth century, Brazil had imported a large number of Africans, both slaves and freedmen, and was bringing in more.

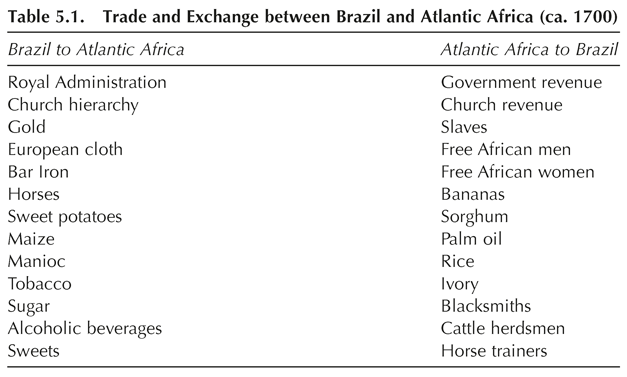

The coastal towns were also developing commercial exchanges with Africa. Brazil exported sweet potatoes, maize, and manioc, which became staple crops in Africa, and imported bananas and sorghum. When, despite Spanish regulations, Peruvian silver was being smuggled from Peru into the Rio de la Plata area, it became the most common way of paying for imports from Africa. Increasingly the most important import from Africa was slaves, but the trade also included other commodities. As the cross-Atlantic trade grew, Brazil played an ever-larger role in Atlantic affairs. No longer a neglected backwater, by 1600 Portugal’s trade with Brazil was more valuable than its spice trade with Asia.

Brazil was also becoming the economic and administrative center of a South Atlantic commercial and administrative network. Brazil exported tobacco, sugar, manioc, beans, flour, spirits, cloth, and sweets to various ports on the African coast. Africa in turn sent Brazil slaves, palm oil, rice, and ivory, along with Asian luxuries left in African ports by ships on the way to Lisbon from India.23 São Salvador da Bahía became the focal point for more South Atlantic contacts when the Portuguese Crown transferred management of its African holdings from Lisbon to the governor in Bahía. The ecclesiastical administration was also reformed, and African bishops were put under the supervision of the archbishop of São Salvador de Bahía.24 The economic links across the southern Atlantic grew stronger, along with the number of sugar plantations. The cross-Atlantic urban network grew even stronger with the 1690s discovery of gold in the Brazilian region now known as Minas Gerais. Before long, the exchange of gold for slaves became a major part of South Atlantic commerce. By the 1750s, Bahía was a city of some thirty thousand people and the capital of a unique maritime province that included both Brazil and the Portuguese holdings in Atlantic Africa.

Lauren Benton suggests that the cross-Atlantic linkages were deeper and more informal than the commercial, administrative, and ecclesiastical connections.25 The integration of African slaves, some of them skilled artisans, into Brazilian society brought with it a blend of Portuguese and African legal traditions. African slaves provided important skills, especially horse breeding and training, the care of livestock, blacksmithing, and rice cultivation. As slaves became freedmen and formed part of the artisan class, they reinforced the amalgamation of the two legal traditions. Brazil was the point of departure for more far-reaching links in what was becoming the “Atlantic World.”

By the 1620s the Atlantic world was changing rapidly. In Brazil the supply of Native American slaves dried up by 1600, and plantation owners were replacing them with African slaves. In Europe the Dutch had won their independence from the Habsburg Empire, and in 1621 they went to war with the combined Spanish and Portuguese Empires, then ruled by the young Philip IV.

Since Portuguese Brazil was one of the richest colonies in the Atlantic region, the Dutch set out to conquer it. They created the Dutch West Indies Company on the model of the Dutch East Indies Company, with the power to both regulate trade and go to war on behalf of the Dutch Republic. The first attack on Recife, on the easternmost tip of Brazil, in 1624–1625 was driven off after several months of Dutch occupation. In 1628, however, the Dutch staged a successful invasion that became a twenty-six-year occupation of the northern, sugar-producing, part of Brazil.

While the political and economic situation of Brazil changed with the arrival of the Dutch, colonial society retained it earlier traits. With virtually no European women, Dutch soldiers and traders replicated the practices of their Portuguese predecessors and acquired Native American partners. In some cases, the wife was baptized and became part of a formalized Tupi-Dutch marriage. The requirement for a formal marriage was religious, while race was unimportant. This marks a contrast with the more tightly controlled society in the towns of New Netherland.26

The Dutch then encouraged the Sephardic Jews of the Netherlands to modernize the Brazilian sugar industry and direct its trade away from Lisbon and toward Amsterdam. To guarantee the continued supply of labor for the expanding plantation economy, the Dutch also captured the Portuguese slave trading post at Elmina in 1637; by 1642 they controlled all the European trading posts along the adjacent Gold Coast, now the coast of Ghana. This facilitated the rapid expansion of plantation society into the Caribbean, reflected in Europe’s consumption of sugar.

Portugal forced the Dutch to return most of Brazil in 1654, after which the Sephardic Jews left Brazil or converted to Christianity to avoid the Portuguese Inquisition. These Sephardic Jews became part of a Jewish trade diaspora that spanned the Atlantic, Europe, and the Mediterranean. With trade contacts all around the Caribbean and the Atlantic, some of these Jewish families returned to the Dutch Republic; others settled on the Caribbean islands of Curaçao and Jamaica or in New Amsterdam (after 1664, New York). This put the Sephardic Jews in an ideal position to trade across imperial boundaries. As a result, while the Dutch West Indies Company tried to control Atlantic trade, the Sephardic Jews ignored its regulations and traded across the boundaries between Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English jurisdictions. They quietly traded directly with African agents to obtain slaves, and when the Brazilian gold mines opened up, they gained control of a large part of the Brazilian gold trade, often evading Portuguese regulations. Similarly, when diamonds were discovered in Brazil in 1720, the Sephardic Jews, who already had a role in the diamond trade of Amsterdam and London, were well placed to control much of the Atlantic diamond trade.27

Dutch activity in the Caribbean also facilitated the dispersion of the Sephardic Jews after 1654. This coincided with the breakdown of Spanish control over most of its islands in the Caribbean. At this time, seventeenth-century Spain was preoccupied with exploiting its American mining empire and with the safety of the treasure fleets bound for Europe. As a result, except for guarding the route of the silver fleets from America to Europe, the Spaniards were paying little attention to the Caribbean they once had conquered.

By 1655 the Dutch, English, and French all had control of important Caribbean Islands. The Dutch base in Curaçao became a major clearinghouse for goods and slaves smuggled into the Spanish Empire. The English meanwhile had conquered Barbados (1625), several smaller islands, and a much bigger prize, the island of Jamaica (1655).

Meanwhile, promoters in England were reacting to the potential profits they saw in the tobacco trade. For the first twenty years of colonization in the Caribbean, the English concentrated on recruiting indentured servants from Europe to create both tobacco plantations and small farms on which freed indentured servants could establish their own farmsteads. As the 1640s saw the rapid spread of sugar production in the Caribbean, including its English colonies, large landowners shifted over to sugar on their own lands and aggressively bought out small holdings. This forced the white farmers in the islands to move, first to Jamaica and later to North Carolina and New Jersey.28

The French captured Guadeloupe and Martinique (1635, 1636), and the western half of the island of Santo Domingo, which became the colony of Haiti (1663). As the plantation system spread across the Caribbean, the Dutch provided slaves, transported sugar, and thereby facilitated the opening of new plantations. Many plantations became so specialized that they could not feed their own slave populations. As we will see, this gave the Atlantic colonies of New England, New York, and Pennsylvania markets for their wheat, flour, and other foodstuffs, providing them with the profits they needed to buy imports from England.29 As sugar spread beyond the Portuguese controlled area, it became the engine that helped knit together a trans-Atlantic commercial network with similarities to that of the Indian Ocean.

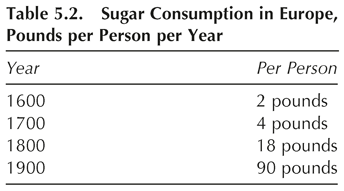

This poses the question: “How was it that sugar could transform the Atlantic economy and trigger the forced migration of twelve million to thirteen million Africans?” The answer is implied by the figures in table 5.2. In the context of a preindustrial world largely populated by people with little or no disposable income, sugar became a unique commodity.

Unlike almost any other commodity in the preindustrial economy, sugar had a very elastic demand. In the case of most goods, an increase in the supply will cause the price to fall. The seller will sell a few more items, but not enough to prevent a drop in the total profit. In other words, it did not pay to expand production too fast.

Sugar was unique in that it was a commodity that had to be produced far from its final market. In a world with limited flavors and no refrigeration, the sweetening effect of sugar made it close to addictive. Once people had used sugar, they eagerly rearranged their personal economies in order to buy more. If the seller increased the supply of sugar on the market, the price would fall, and he would make less profit on each bag of sugar. This could work to the seller’s advantage if, in the case of sugar, a lower price attracted a great many new buyers. Unlike most goods in an early modern market, cheaper sugar attracted and kept enough new buyers so that, despite the reduced profit per unit, enough more units were sold that the smaller profit per unit produced a larger total profit. This is the underlying reason for the steady expansion of sugar production.

To make the sugar cheap enough to sell profitably, the plantation owner needed an ideal set of inputs. One was good land, preferably free, as it often was in the New World. Along with free, or nearly free, tropical land, the plantation needed European capital and management. Finally, the plantation needed an ongoing supply of cheap labor.

As sugar plantations appeared in Brazil, the first recourse was to enslave Native Americans, since it was cheaper to capture local Indians than to buy imported African slaves. By the early 1600s, 90 to 95 percent of the Indians along the coast of Brazil had either died of European disease or had fled far into the interior. Brazilian plantation owners routinely sent slave-hunting expeditions into the forests to sweep up any available Indians. Few Indians could be found within 185 miles of any Portuguese town. With fewer and fewer Native American slaves available, plantation owners had to shift to African slaves. The English on Barbados went through a similar transition in the 1620s and 1630s. Initially committed to raising tobacco and using English indentured servants, when the landowners shifted to sugar production, they forced the tobacco farmers, often former indentured servants, off the land and consolidated it into large plantations. The indentured servants were replaced with African slaves.30

The combination of good, cheap land, African slave labor, European capital, and an indefinitely elastic demand curve created a new kind of economic institution. The Atlantic sugar plantation operated like a modern factory, with slaves bought and depreciated like machines.31 Sugar was a part of the economy that widened Brazil’s connections to the Atlantic world, driving the expansion of Brazil for most of the seventeenth century.

The slave trade has come up repeatedly in talking about Portugal, Africa, and Brazil. Historically, slavery was a long-established institution in both Mediterranean Europe and Africa. It was an integral part of both societies and since Roman times had included African slaves brought to the Mediterranean across the Sahara. Thus, it is hardly surprising that, even on their very first raids on the African coast, the Portuguese brought home small numbers of African captives to sell as slaves. The conditions of this slavery varied widely, and in some Mediterranean countries it could include a recognized civic identity. Up to a point, the slave trade along the African coast was a logical extension of the centuries-old intra–West African slave trade. Slaves were used in large numbers in the gold mines of Mali and in a wide range of domestic and commercial services throughout Africa. Slaves in Africa worked as mine laborers, household servants, artisans, and soldiers in the armies of Mali, Songhai, and Benin. This defines indigenous African slavery as a large institution in its own right.

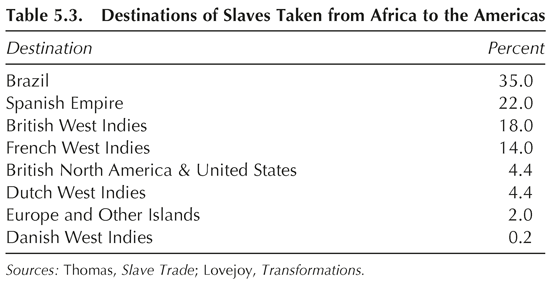

The slavery we know about on large-scale Atlantic plantations was significantly different from its earlier, more traditional African forms. Its beginnings go back to the fifteenth-century sugar plantations on Madeira and São Tomé. As African slavery spread to Brazil, the Caribbean, and the southern colonies of English North America, it became vastly larger than any earlier Mediterranean or intra-African slave trade. By 1700 about four million Africans had been exported to the Americas, with Brazil the largest buyer.32

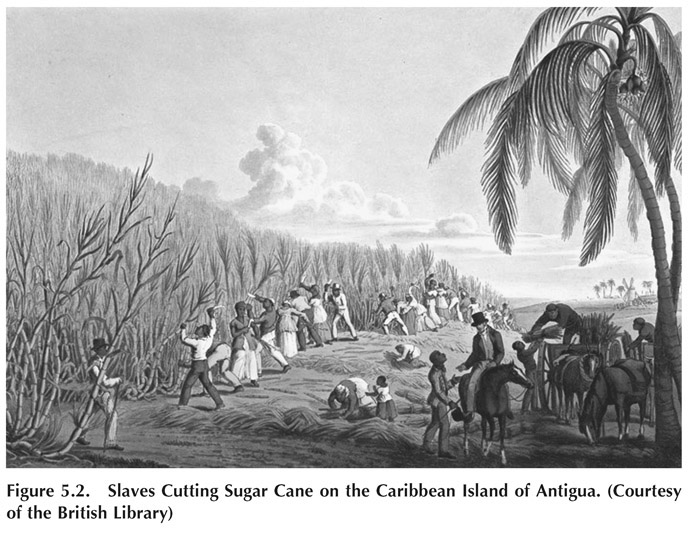

Sugar production involved a grim reality: Sugar cane only grew in the tropics, and it needed a large amount of hard labor. It required an endless cycle of burning debris, digging it in, planting the cane, cutting it, hauling it to the mill, pressing the cane, and drying the sugar. The work was hard, slaves often died young, and an active plantation required a constant stream of replacement slaves. In the seventeenth century English West Indies planters imported 265,000 slaves between 1600 and 1700; only 100,000 were alive at the end of the century.33

The growth of the plantation economy and the slave trade is reflected in the growth of the slave trade itself. From 1551 to 1575 the slave trade brought about twenty-five hundred Africans to America every year; that number reached four thousand a year from 1576 to 1600. A century later the average for 1651–1675 was fifteen thousand; for 1676–1700 it reached twenty-four thousand per year.34

When the Dutch occupied the northern half of Brazil and modernized its sugar industry, they also made sure of a continuing supply of slaves by capturing the slave trading posts along the Gold Coast. The economic links across the southern Atlantic grew even stronger with the development of more sugar plantations, and they were further strengthened by the discovery of gold in Brazil in the 1690s. On the African side of the South Atlantic, African slave dealers were ready to sell slaves to brokers on São Tomé and the Cape Verde Islands for gold because it allowed them to import more European products for the African market.35

While Brazil was the largest single customer for the slave trade, and the Portuguese were prominent participants in the trans-Atlantic part of the trade, increasingly it was also carried on by traders from Spain, France, England, Holland, Denmark, and Sweden. The slaves ended up in Brazil, the West Indies, Spanish Central America, in Mexico (both on plantations and in the silver mines), in Peru, and in all of what became the thirteen North American colonies. As we will see, 40 percent of the population of Virginia in 1700 consisted of slaves. Without their labor, sugar, and later tobacco, coffee, and cacao, could not have been produced as cheaply as it was, and the Atlantic economy would have developed very differently.

Sugar—and later tobacco, coffee, and cacao—was a new phenomenon in the world of trade and commerce. Most early modern long-distance trade involved goods that were relatively valuable for their size and weight. They were commodities destined for the small, upper-income part of society, and that market was easily glutted. The rationale behind the chartered companies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was to regulate the supply of foreign goods so as not to glut the market and drive down prices.

Sugar and similar products had equally exotic origins, but they became mass consumption commodities. They appealed to people who could afford to buy only in small quantities, but there were enough of such people to produce profits even at what seemed like low prices. Not surprisingly, the slave trade grew in tandem with the production of goods like sugar. By one estimate, the Americas exported about twenty thousand tons of sugar in 1600; by 1775 the figure was two hundred thousand tons.36

The boom in trans-Atlantic trade reflects an integrated and expanding Atlantic economy. How important this was in triggering the Industrial Revolution remains an open question and has been hotly debated.37 The similarity between a sugar plantation and a capitalized industrial factory is clear.38 The growing demand for exotic goods clearly reflects changing economic choices among European consumers. We can never forget, however, that this growth came at the expense of dispossessed Native American societies and at the expense of the twelve million to thirteen million Africans who were taken from Africa as slaves, two to three million of whom died crossing the Atlantic.