CHAPTER SEVEN

For historians of Europe, the opening of the route around Africa has a heroic quality. When Vasco d Gama reached India, it was a spectacular feat of navigation, but its importance has been overstated. Before we can grasp just how Europe related to Asia, we need to know more about the geography and technology of world trade in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The two factors that really shaped the global economy over the next two and a half centuries were the Chinese market and American silver. Vasco da Gama’s cargo of European merchandise found few buyers in India, and even with recurrent use of force, he headed home with only a few hundred pounds of pepper in otherwise empty cargo holds.

Da Gama’s route was the first really new addition in centuries to the available routes between Europe and Asia, and for a time the Portuguese enjoyed a near monopoly on the supply of Asian spices in Western Europe. Western Europe, however, accounted for only a small part of Asia’s trade in spices, and the older routes continued to serve the Middle East, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Eastern Europe. Once the Asian commercial world adjusted to Portugal’s intrusion and the Asian political situation had stabilized, the Portuguese dream of a monopoly over the Asian spice trade melted away.

From an Asian perspective, the Portuguese simply added one more intercontinental route to the many that were already available for trade between Asia and Europe. The European urge to reach Asia was not a matter of ending European isolation; Europe had been part of a long-distance trade network since Roman times. Da Gama’s voyage was an attempt to improve trade with Asia at a time when political unrest was interfering with the traditional trade routes. The addition of a new route in 1498 had an important impact on the European spice trade, but as we have seen, great empires were taking shape along with a vast network of autonomous seaports and market centers. It is a bit Eurocentric to credit da Gama’s addition to that network as reshaping history. At the height of Dutch, English, French, and Portuguese trade with Asia, the Cape route carried less than 20 percent of Indian Ocean trade. While this trade became important to Europe, especially in the seventeenth century, European participation had little effect on most aspects of Asian trade until the late eighteenth century.

It is likely that the rapid increase in the world’s silver supply, coming from Mexico, Peru, and Japan, was more important to world (or European) trade than the route around Africa. America began exporting huge quantities of silver around 1560, and because silver gave Europe a commodity with ready markets in Asia, Europe was able to buy increasing amounts of Asian products from Middle Eastern middlemen. This provided the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires with more silver for their own trade. Before we look at Europe’s role in world trade, we need some sense of the scope of the African-Eurasian network the Portuguese sought to join in 1498.

The Indian Ocean and the South China Sea constituted the core of the world’s long-distance trade, and the two most important participants were China and India. The markets for their exports—spices, silks, cotton cloth, gemstones, and porcelains—were located all around the Indian Ocean and as far away as Japan, the Middle East, and Europe. Over the centuries the merchants of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea had developed sophisticated, interlocking trade networks designed to move high-value merchandise through those networks as efficiently as possible.

Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century ships, whether Asian or European, could not tack very well against the wind. Asian sailors had long since figured out that the physical geography of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, together with seasonal winds, created three distinct maritime zones. The prevailing winds in the Indian Ocean blow out of the northeast between October and April, favoring trade from India to the Red Sea and East Africa. In the spring the winds reverse and blow from the southwest to the northeast, favoring trade from Africa to India. The pattern is similar in the South China Sea, but the seasonal changes in the wind come a month or two later.

These seasonal patterns encouraged the development of three trade zones. To the east was the South China Sea, bounded by China, the Philippine Islands, Borneo, the Malay Peninsula, and Vietnam. The Bay of Bengal defined the middle zone, with India to its west and the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra to the east. The western zone, defined by the Arabian Sea, was bounded by Africa to the west, India to the east, and Persia and Arabia to the north. Since most merchants and shippers operated within only one of the three zones, the high-value goods of intercontinental trade moved in stages, from one zone and its merchants to the next.

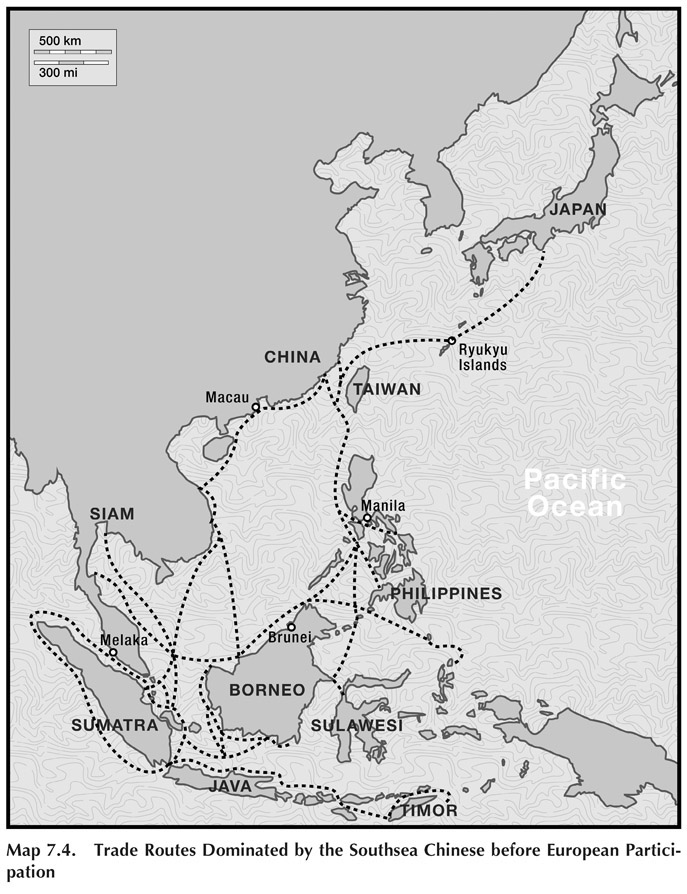

In the early fifteenth century, the Chinese economy generated an important part of the world’s long-distance trade and dominated trade in the eastern trade zone. Chinese merchants and shipowners controlled most of the trade between the ports that surrounded the South China Sea, and most of this merchandise was shipped in Chinese junks sailing between Java, Melaka, the Philippines, and China. Most of the merchants were known as Nanyang, or Southsea Chinese, and constituted an informal but widespread trade and data network. The eastern trade zone also included Malay traders and Japanese, whose ships appeared regularly in the South China Sea, stopping first at the island Kingdom of Ryukyu (Okinawa) and then at the Kingdom of Champa on the way to the emporium at Melaka.1 Chinese merchants had settled in ports all around the South China Sea during the Yuan and early Ming dynasties and could be found in Aceh, Java, Cambodia, Champa, Brunei, and Ayutthaya (Thailand). This network was then augmented by refugees from the Manchu invasion and takeover of the Chinese Empire in 1644. The result was an ethnically defined Chinese trade diaspora that connected every part of the South China Sea, from Formosa to the Philippines to the Straits of Malacca, prompting the phrase “the Chinese Mediterranean.”2 After 1435, official policy in China discouraged the construction of large ships and limited foreign access to China. This “withdrawal” was evaded or ignored by imperial officials in Canton and Guangzhou on China’s southeastern coast, where merchants and capital continued to engage in a remarkable amount of overseas trade.

The middle zone, the Bay of Bengal, lay between India and Sumatra. This zone sustained a complex trade in Indian cottons, Southeast Asian spices, gemstones, gold, and silk cloth. The gold and silk were brought overland from China into the Taungoo Kingdom (now Myanmar) over a busy caravan route between the two countries. Since crossing the Bay of Bengal was a relatively long trip on the open sea, merchants there used larger ships, usually Arab dhows or Chinese junks. The most important group of merchants in this zone were the Hindu Chettiars from the east coast of India, but they shared the trade with Malays from the spice-producing Maluku Islands of Southeast Asia and the Gujaratis of northwestern India.

The third and westernmost Indian Ocean trade zone, known as the Arabian Sea, connected western India with Persia, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the east coast of Africa. This region was the site of a loose commercial triangle. The eastern side linked India to the trade routes that carried Asian goods via the Red Sea or Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean and Europe. The western side connected the maritime city-states of East Africa with the same trade routes to the Mediterranean. The southern side of the triangle linked East Africa’s supply of gold, ivory, and slaves directly to Southwest India and the emporia that stocked the spices and silks from farther east. Much of that trade was carried in small ships that worked their way along the coast between India, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea.

This huge, three-zone Indian Ocean–South China Sea commercial network extended beyond its regional limits both into the Pacific and through the Middle East in several directions. From the South China Sea, ships sailed north to the Ryukyu Islands, Korea, and Japan. A second route extended south and east from Melaka to the spice markets at Makassar and Ternate. A third ran from the spice islands north to Manila and on to either Japan or China. At the western end of the Indian Ocean network, a trade route ran through the interior of the Safavid Empire to the Caspian Sea and Muscovy. Other routes ran up the Persian Gulf to Aleppo and the Eastern Mediterranean or up the Red Sea to Cairo and Alexandria on the south shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Even farther afield, trade routes reached Constantinople, Venice, Northwest Europe, and North Africa.

Within the Indian Ocean, the process of relaying commodities across trade zones was coordinated by five distinctive seaports, usually referred to as emporia. These emporia have been mentioned in various places in this essay; now we have enough information to see how they coordinated an intercontinental commercial network. Emporia were more than seaports providing import/export services for their hinterlands. They also linked points in the trade zones in the Indian Ocean with those in the South China Sea and maintained commercial ties that reached beyond the Indian Ocean to Japan, Central Asia, Europe, and North Africa. As of 1497, five emporia organized the flow of trade across the Indian Ocean.

In the 1400s, Melaka, located on the Strait of Malacca, was probably the most important of these emporia. Located near modern Singapore on the Malay Peninsula, Melaka was the place where trade from the Indian Ocean to the west, the South China Sea to the east, and the Malukus intersected. Melaka housed literally hundreds of merchants and their families, the largest groups being the Chettiars of India, the Southsea Chinese, the Malays from Makassar and the Malukus, and the Gujaratis of northwestern India. The sultan of Melaka recognized four self-governing ethnic merchant communities, negotiating with them through their internally selected leaders. The Chettiars were Dravidian-speaking Hindus from Tamil Nadu on the Coromandel Coast of eastern India. They had been established as merchants in Melaka before its conversion to Islam in 1414, but in the fifteenth century they found their trade position in Melaka challenged by Muslim Gujarati merchants. The Hindu Chettiars thought the newly arrived Muslim Gujaratis were being favored by the Melaka’s Muslim sultan. This left the Chettiars disaffected and willing to help the Portuguese capture the city once they had arrived. As a gauge of the importance of the trade at Melaka, that port alone handled most of the spices traveling to India, the Middle East, and Europe, as well as half of the spices destined for the China market.3

Calicut, an emporium near the southern tip of India, was the meeting place for traffic arriving from Melaka to the east and for ships crossing the Arabian Sea from East Africa. A cosmopolitan commercial center, Calicut housed merchants from Egypt, Syria, West Africa, Persia, Gujarat, North Africa, and from Deccan, Bengal, Ceylon, and Melaka.4 Calicut also had a large community of Indian Christians, members of a branch of the Syrian Orthodox Church that had been established on the west coast of India for almost a thousand years. Known as the Saint Thomas Christians because, according to tradition, Christianity had been brought to the area by the Apostle Thomas, this community controlled the region’s export of Indian pepper.5

Surat, an emporium on the northwest coast of India, also serviced the east–west trade between India and the Middle East. In addition, Surat was the port of entry for goods headed overland to the emporia cities of Lahore and Multan. In these two inland caravan cities, merchandise was loaded onto the camel caravans that crossed Afghanistan to Samarkand, Lhasa, Kabul, Kandahar, Tabriz, Aleppo, Izmir, and Constantinople.

Hormuz, an emporium city at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, sent goods by ship, riverboat, and then caravan through Baghdad to the inland emporium city of Aleppo.6 Aden, an emporium city at the entrance to the Red Sea, provided a base where goods headed for the Mediterranean were repackaged for transfer to smaller ships that were better suited to the tricky navigation of the Red Sea. Most of this merchandise was then carried to Cairo and ultimately to Alexandria for distribution around the Mediterranean.

Larger than most seaports, emporia were the nerve centers of long-distance trade. They provided a range of financial and maritime services, including merchant-bankers who provided commercial credit and shipping insurance. Emporia also provided brokers and factors that stored, processed, and repackaged commodities for further transit. An arriving ship captain could expect to find a wide variety of merchandise to carry as cargo, repair facilities for his ship, and supplies of food for the next voyage.7 Emporia were populated by people from all over Eurasia, including merchants from Egypt, Syria, Africa, Gujarat, the Mediterranean, Persia, Bengal, Melaka, China, Japan, and Armenia. Each of these emporia had commercial relations with dozens of commercial city-states within its adjacent maritime zones. Collectively, these emporia and their satellites made up a remarkable network of interdependent commercial centers, few of which were fortified.

These maritime connections were only part of the picture. Maritime transport was also part of an integrated network that included overland connections, usually by camel caravan. The caravan routes connecting the Mediterranean and the Near East with China and Southeast Asia began where the Ganges River emptied into the Bay of Bengal. When politics allowed, trade traveled on riverboats up and down the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers, where one of most important stops was Delhi, capital of the Sultanate of Delhi. The caravans then went either to Lahore or Multan in the Indus River Valley. There they met caravans traveling north from the seaport of Surat. From Multan and Lahore, caravan routes extended to Kandahar or Kabul, and then west to the Caspian Sea. Along the way, that route was joined by caravan trails from Samarkand, Bukhara, and other Central Asian cities and by a caravan route that came north from the port of Hormuz through Isfahan on the way to the Caspian Sea. From the Caspian Sea and northwest Iran, caravan routes stretched north as far as Moscow and west to Aleppo, Izmir, Constantinople, and Trebizond on the Black Sea. Another caravan route connected Basra on the Persian Gulf with Baghdad, the market at Aleppo, and the Mediterranean port of Iskenderun, while routes from the Red Sea went to Cairo and Alexandria. Farther west, a set of caravan routes linked the north coast of Africa with sub-Saharan West Africa, connecting Mali and the cities of Djenné, Gao, and Timbuktu with Algiers, Tunis, and other North African ports. Seen in conjunction with the maritime routes across the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, and South China Sea, the caravan routes were part of a huge, integrated network that offered long-distance merchants several combinations of maritime and overland routes.

The scope of this transcontinental network is striking, but it is even more impressive when we consider the physical or technological capacity of pre-industrial trade and travel. Because few long-distance roads were more than walking trails, most long-distance overland trade was done with pack mules, camels, or horses. A pack mule usually carried 250 to 300 pounds of cargo, and a train of fifty mules, with its ten to fifteen muleteers, could move seven tons of merchandise about twenty miles a day. Camels were better suited for long desert routes. On long trips a dromedary camel of the Middle East could carry 350 to 400 pounds and travel about twenty miles a day, provided it was allowed to rest every three or four days.8

In the few areas where rough roads allowed the use of two-wheeled ox-carts, a train of thirty carts could carry fifteen tons of cargo ten miles in a day. This sounds more efficient than pack animals, but oxcarts moved slowly and took twice as long to reach a destination as a camel caravan or mule train. A large mule- or horse-drawn four-wheeled freight wagon could carry up to four thousand pounds and travel about twenty miles a day, but it needed two to four mules or horses and a well-constructed road. Carts and wagons may look more efficient than pack mules or camels, but they only work when some authority has invested in building and maintaining an adequate road.

The one thing that reduced the cost of moving goods was water. The same pair of mules that could carry eight hundred pounds of freight overland could pull a canal or riverboat loaded with twenty tons of cargo. From early times, rivers like the Danube, Rhine, Nile, Euphrates, and Ganges were used by small boats or lined with towpaths for mules pulling barges. In China the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers were linked together by the Grand Canal, allowing the inexpensive transfer of bulky commodities like wheat and rice over long distances. As a result, China became the largest inland market area in the world, one that sustained specialized industries, intensive agriculture, and large cities with concentrations of elite buying power.

For areas near the sea, sailing ships offered the cheapest and fastest transport available—as long as their holds were full. A ship with a capacity of three hundred tons and a crew of forty could carry bulky goods for hundreds of miles without dramatically raising the final price of its cargo. While the cost of carrying a ton of goods one mile by ship was a fraction of the cost of overland travel, this bargain had limits. Ships did travel faster than overland caravans—easily a hundred miles in a day compared with twenty—but ships rarely traveled in a straight line. The distance traveled between ports was determined by prevailing winds and was usually far longer than it would appear on a map. Sailing ships represented large capital investments and had a limited lifespan, especially in warm, tropical waters. On really long trade routes, they rarely lasted for more than two round trips. Moreover, ocean travel was inherently risky, and big ships required large investments in adequate docking facilities. They also needed wholesale markets big enough to handle large cargos, or big cities with large, wealthy elites and good distribution networks that reached wealthy consumers in outlying towns.

To exploit the cost savings in the use of larger ships, the commercial world needed concentrated markets and convenient waterborne transport services. The merchant’s biggest problem was finding enough affluent customers in a given area to absorb a large cargo without flooding the market. The size of that market was limited if one had to use too much ground transport to complete the retailing of the goods.

The nature of this problem is suggested by some basic demography. The world of 1500 had only about 425 million people and only a handful of cities with more than 250,000 inhabitants. Agricultural productivity was low, and 80 to 90 percent of the population worked the soil or tended livestock in order to support the 10 percent that was not engaged in agriculture. Most people lived in scattered villages of two hundred to four hundred people, and a city of twenty-five thousand was a metropolis. The few people who had much discretionary income were dispersed among dozens of towns. These demographic realities help us understand the importance of large new capital cities. By drawing wealthy elites to live at court, new capital cities helped provide merchants with concentrated markets.

While most of the profits in long-distance trade depended on the sale of high-value goods to wealthy elites, the emphasis on high-value goods is deceptive. A ship or camel caravan that carried compact and valuable commodities in one direction needed a return cargo. That cargo depended on what a local freight agent or broker could arrange. Rather than return empty, the ship’s agent or the caravan master would accept a cargo of everyday goods if they could be sold at the destination for enough revenue to pay for the initial purchase and even part of the overhead for the return trip. As a result, the lists of long-distance cargoes included a surprising number of everyday commodities alongside the high-value goods that made up the really profitable cargoes.

If the geographic extent of the Eurasian trade routes is striking, European observers were also struck by the ethnic diversity of Asian seaports. They invariably had resident communities from all parts of the Indian Ocean, communities that spoke a variety of languages and practiced various forms of religion: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Animism.

One of the hardest things for many Europeans to adjust to was the importance of Islam in the world of Eurasian commerce. From East Africa to Japan, the commercial world of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea was shaped by certain realities. Muslim society in general did not suffer from the stigma that Europe’s landed nobility attached to commercial wealth. European cities were governed by city councils controlled by a combination of landed magnates and commercial notables. This usually established a close connection between economic policy and the preferences of the commercial oligarchy. While the Muslim port cities lacked such “republican” institutions, and the position of sheik was hereditary, the fact that the ruler was often part of the commercial elite normally precluded arbitrary or confiscatory rule.9 The fact that Islam attached no stigma to commercial wealth, while in Europe the landed nobility considered itself superior to the merchant community, made it easier for Muslim landed elites to invest agrarian profits in trade.

At the same time, Islam had a tradition of toleration toward the “Peoples of the Book.” Initially this applied to Jews and Christians, who were recognized as subjects of Muslim rulers provided they paid a small head tax. Faced with large non-Muslim populations, Muslim rulers in India, the Safavid Empire, and the Ottoman Empire developed rationales for similar forms of tolerance to religious communities from outside the Old Testament tradition. As a result, any Muslim-ruled commercial center tolerated numerous ethnically distinct merchant communities, including Muslims, Armenian Christians, Jews, Animists, Sikhs, Chinese, and Hindus, often granting formal autonomy to non-Muslim ethnic communities.

Despite this cultural and linguistic diversity, merchants from Europe to Japan carried out business transactions in very similar ways. Regardless of religion or ethnicity, business was transacted by individuals or by partnership companies in which the partners were family members, close relatives, or relatives by marriage. It was a world based on the same family-oriented values that were the foundation of a European’s personal identity. As we observed earlier, Europeans were conditioned to seek personal achievement in ways that enhanced the reputation of their extended families, with the result that they could relate to similar family structures in other parts of the world.

The foundation of the whole commercial system was credit. Credit, in turn, depended on trust and business integrity. In a world in which transactions were completed across great distances, over long periods of time, and between people speaking different languages, one had to be able to trust both intermediaries and final recipients who were total strangers. This put a premium on doing business with members of one’s extended family. It explains why the family ethos was so important and why families were often widely dispersed within the commercial network. Agreements were usually defined in written contracts, and commercial city-states usually had judges or employed arbitrators who enforced the terms of contracts. At the same time, verbal agreements based on the equivalent of a handshake were considered equally binding. The objective was to make a profit, but any transaction had a nonmonetary component as well. A properly implemented contract not only assumed a profit but also enhanced the extended family’s reputation for reliability and integrity. It enhanced a merchant’s political connections and, in India, his standing within his caste. These unwritten rules were enforced by peer pressure, reputation, and the threat of ostracism. While profit could be counted in monetary terms, a “good outcome” in business included much more than just monetary profit.

Commercial honesty was reinforced in market towns, whether in Europe, Africa, or Asia, by agents and institutions appointed to facilitate trade. This included resident brokers who kept track of current inventories, merchant bankers willing to extend credit, translator/go-betweens, and courts designed to settle commercial disputes. In some places the brokers were assisted by officials who weighed, measured, and certified the quality of goods. In Indian Ocean ports, where merchants spoke several languages, commercial facilitators generally included translators or, in the Portuguese colonies, lenguas.10 In the South China Sea, the Portuguese also used local language experts, orjurebasas.

This ethos of commercial integrity was as important in Europe as in the Indian Ocean, but its application was complicated by ideological differences. This was especially true among the Portuguese. Part of Portugal’s landed aristocracy remained committed to the medieval ideal of a Christian crusade against Islam. These differences in perspective between factions at the Portuguese court explain some of the inconsistencies in Portuguese behavior once they found their way around Africa into the Indian Ocean. When the Portuguese arrived in the Indian Ocean, they found that most Indian Ocean seaports were controlled by Muslim elites. While the Portuguese learned to deal with Muslim governments, they were often hostile to Muslim merchants. Muslim merchants were not welcome in most Portuguese-governed ports, and the Portuguese occasionally disrupted the pilgrim trade to Mecca.

The Indian Ocean was ringed with small and mutually dependent port cities that had no need for serious military defenses. In Southeast Asia, port towns sometimes used a defensive tactic that was hard to defeat. The typical port town in this region was spread across an open river valley site, with few defensive walls. Most buildings were built of bamboo, with woven matting walls, wood floors, and thatched palm roofs. They were lightly built and easily replaced; even the aristocratic residential core had little more than a bamboo palisade thrown up when war threatened. This inexpensive infrastructure gave these towns considerable mobility. When some of the Malay city-states in the Straits of Malacca faced aggression from the Sumatran city of Aceh, they simply disassembled their city and moved inland far enough to discourage seaborne raids. On more than one occasion, raiders arrived at a town they had targeted only to find a few abandoned buildings.11

Given the obstacles of distance, time, and risk, it took an enormous amount of ingenuity, trust, and integrity to sustain a complex network of long-distance trade. However powerful the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, or English looked from Europe, European trade could not have functioned without collaboration from preexisting local, regional, and international merchants and governments.

As we have seen, the keys to trade and credit were trust and integrity, usually based on the extended family firm. Individual success came from reinforcing the status of family and clan. A successful business depended on working partnerships reinforced by marriage, internships, adoption, and fictive relationships. While this was true of trade in general, trust and integrity were reinforced in long-distance commerce by distinctive communities referred to as trade diaspora societies.

Each of these diaspora colonies maintained its distinctive language and usually practiced marital endogamy. Scattered along trade routes, these colonies provided their compatriots with ready-made local business contacts. A significant part of the world’s long-distance trade was managed by merchants who were members of trade diasporas and did not identify with any one city, country, or ruler. These merchants systematically placed colonies in trading centers strung along important trade routes. The inhabitants of these colonies retained their distinctive language and religion and married women from other colonies in the diaspora or from their original homeland. Merchants, family members, or formal friends could visit any town in the diaspora’s network and find relatives, friends, or family members who specialized in finding connections with local commercial enterprises. A diaspora could extend over only a few hundred miles of trade routes, like those in Africa cited by Philip Curtin, or be a global network, like those of the Armenians and the Jews.12

Four examples stand out among the many diasporas that helped integrate long-distance trade. Among other things, they illustrate that Europe had no monopoly on entrepreneurial skills. Together, the Multani of India, the Overseas Chinese, the Jews, and the Armenians illustrate the ways in which trade diaspora communities maintained their cohesion.

The internal cohesion of diaspora societies reinforced the integrity of business transactions across long distances, over long spans of time, and between very different cultures. Among their many important assets was their ability, as neutral middlemen, to trade across boundaries between warring states and provide communication between governments. They were particularly effective in dealing with the long-term tensions between the Safavid and Ottoman Empires. In that case, the Armenians had several colonies in both empires, and even though the two empires were often at war with each other, the Armenians regularly sold Safavid silk exports at markets in the city of Aleppo, deep inside the Ottoman Empire.

The creation of the Mughal Empire in 1525 brought recovery of the caravan trade across Southwest Asia and growing prosperity to northern India. One indication of India’s economic dynamism was the emergence of a diaspora of thousands of Indian merchants that spread across western Asia from the caravan city of Multan in India.13 Unlike the Armenian or Jewish diaspora, the Multani Indian diaspora was not the result of persecution or forced migration. As the opportunities for trade increased, colonies of Indian merchants settled first in the caravan crossroads of Kabul and Kandahar and then followed the caravan routes to the Persian cities of Isfahan, Tehran, and Shiraz. By the end of the sixteenth century, Indian merchants, mostly from Multan, had followed the caravan routes to the Central Asian cities of Bukhara, Merv, Samarkand, and Tashkent. They also followed the trade route that ran north along the Caspian Sea to the city of Astrakhan, located at the mouth of the Volga River. From there they expanded up the Volga and its tributaries to Kazan, Novgorod, and Moscow.

The Multani do not seem to have maintained a self-conscious organization within their diaspora, but there is ample evidence that the Multani organized their businesses based on the extended family and family firm. While the diaspora started from the city of Multan, it came to include Indian merchants from other Indian cities as well. Unlike most diasporas, the Multani did not depend on a common religion, and its members included Muslims, Hindus, and Jains. The members of this diaspora maintained a degree of marital endogamy, recruiting wives from their home communities in and around Multan. In cities where large numbers of Multani congregated, they developed a collective organization that built and maintained large lodging houses and warehouses for Indian merchants. By 1650 literally thousands of Indian merchants, generally referred to as Multani, lived in Isfahan, Astrakhan, the cities of Central Asia, and Moscow.

Among these Indian entrepreneurs were merchant-bankers as wealthy as any in Italy. They used forms of contract, concessions of credit, and shipping loans just as modern as those being used by Italian or Armenian merchants. They formed companies of ten to forty individuals, pooling capital and spreading risk. At their height, individual merchants had business connections from Moscow to Surat, roughly four thousand miles by road. As an example of their potential as merchants, one Multani merchant based in Moscow left an estate worth three hundred thousand rubles (roughly $7,500,000 in today’s money) in 1759.

The Multani diaspora lost its cohesion in the first half of the eighteenth century. It had depended on safe long distance overland transport, which was hampered by the disintegration of central authority in the Safavid Empire in the late seventeenth century. The situation of the diaspora worsened after 1720 with the decline of effective Mughal government and the loss of safe overland routes within the Mughal Empire. Fragments of this diaspora lasted into the nineteenth century, when it was still possible to find Indian money-lenders in a number of Russian cities.

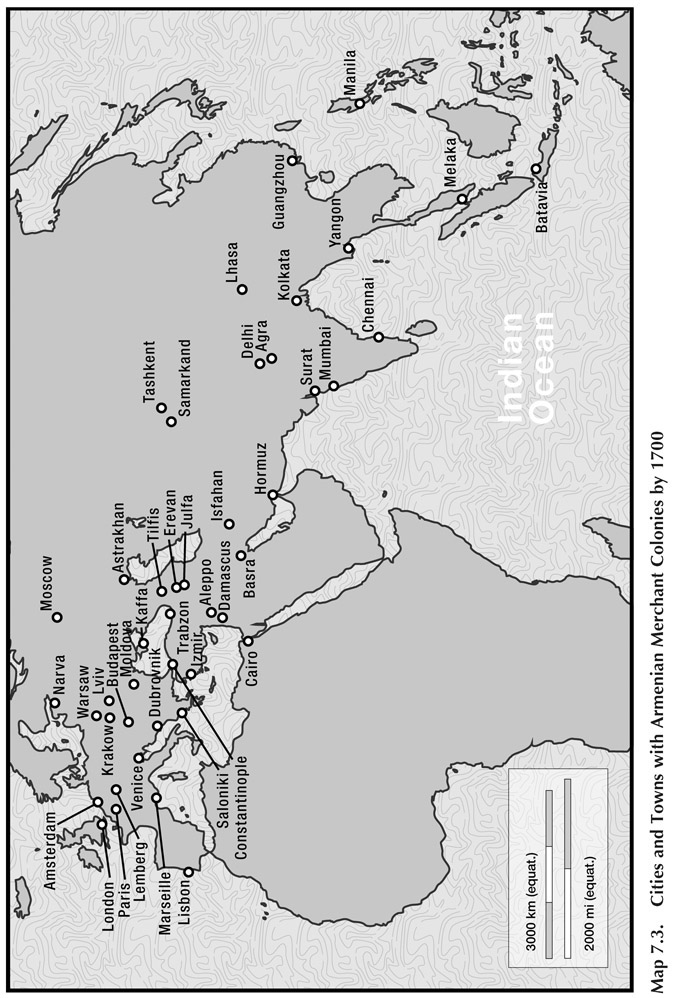

The Armenian trade diaspora originated in the city of Julfa, in what was then Armenia.14 Julfa is now located in a corner of Azerbaijan between modern Armenia and Iran. The Armenian diaspora evolved into a far-flung constellation of colonies. By 1700, the geography of its network stretched from London to Manila. The most important unifying elements in the Armenian diaspora were a long history of dispersal from their original homeland, a distinctive form of Christianity, a distinctive language, and systematic marital endogamy.

At the time of the Roman Empire, the Armenians occupied an area in eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus that included modern Armenia and a third of modern Turkey. They experienced forced migrations under the Byzantine, Seljuk, and Ottoman Empires until their homeland was reduced to the small territory that approximates the modern, post–Soviet Union country of Armenia. They were strongly loyal to what became the Armenian Orthodox Church, a variant of Eastern Orthodox Christianity that separated from mainstream Christianity in the fifth century and developed its own liturgy and an episcopal hierarchy headed by the catholicos, a rank they considered higher than that of patriarch. The Armenians retained their own unique language, which they used for both religious and business purposes. They also maintained a very strong tradition of family ties that operated over long distances, often marrying members of the Armenian community from colonies hundreds of miles away.

By the eleventh century, Armenian merchant colonies could be found along most routes crossing Southwest Asia; and as Europe’s Mediterranean seaports revived in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, they too attracted Armenian colonies. In the 1350s wealthy Armenians were well enough known in Italy to figure prominently in one of Boccaccio’s stories. In 1500 Armenian merchant colonies were present in most Mediterranean seaports and in Surat and Calicut on the west coast of India. As the Portuguese inserted themselves into the world of Asian trade after 1500, they encountered Armenian merchants who helped the new arrivals connect with the local commercial community.15

Because the center of the Armenian diaspora was in the city of Julfa, on the border between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires, between 1603 and 1618 the Armenians were caught up in a war between the two empires. By 1607 the Armenians were virtually refugees. At this point the Safavid shah, Abbas I, persuaded (or coerced) the Armenians to move to a suburb of his new capital, Isfahan. This Armenian suburb has come to be known as New Julfa.

Shah Abbas then adopted the Armenians as a kind of service nobility. The advantages for Abbas were considerable, since he could place imperial finances in the hands of a financially astute cadre that was not linked to the tribal politics at his court. Abbas also put the Armenians in charge of the Persian silk industry. Using their international market connections, they were able to reorganize and expand the export of Persian silk, Abbas’s main source of foreign exchange, and provide Abbas with revenue that he used to improve caravan routes. As the scale of their financial activities grew, the Armenians deferred to a cadre of family elders in New Julfa who managed their relations with the Safavid government.

The Armenians also took advantage of Europe’s growing supply of American silver and the parallel increase in European demand for Asian products. As trade between Europe and Asia expanded, the Armenians were ideally placed to extend their commercial and financial network. In some areas their monasteries even provided basic banking functions, taking in assets for safekeeping and providing credit for international trade.16

In addition to facilitating trade for their compatriots, the Armenians provided brokerage services and credit for other merchants. When the first Portuguese ships appeared in Surat and other Gujarati ports with little in the way of salable cargoes, capital, or credit, the Armenians not only provided them with credit but also connected them with Gujarati merchants who wanted to export Indian goods. A century later, they did the same thing for the English who arrived in India.17

By the mid-seventeenth century, Armenians had established a colony in Manila, where they controlled the flow of American silver to customers in the Indian Ocean, including the English East India Company. Armenians based in India routinely owned or leased ships for trade with Malacca and Manila. They sailed flying an Armenian flag, which virtually all governments recognized and allowed to enter port and trade. This was important for the English and French East India Companies, because the Armenians often carried English and French goods to Manila and brought back the American silver that the French and English needed in their trade with China.18

The Armenians sometimes acted as factors for the English East India Company, arranging cargoes for company ships and occasionally sending their own merchandise to Europe in company ships.19 Because of the security of their overland connections, both the Dutch and English East India Companies used the Armenian courier service. It took less time for letters to travel across Persia and the Mediterranean to London and Amsterdam than for the cargoes from Indonesia or India to travel around Africa. With advance knowledge of what the incoming fleet carried, the home office could manage their markets to maximize profits. By 1700 Armenian merchant colonies could be found from London to Moscow, Isfahan, Surat, Melaka, and Manila.

The early eighteenth-century Armenian merchant banker Khojah Petrus Uscan, mentioned earlier, did most of his business with relatives scattered across Eurasia, illustrating the scope of the Armenians’ trade diaspora. Very occasionally an Armenian would marry someone from outside the community, but such a marriage was always part of a carefully calculated business arrangement, as when the daughter of a prominent family in New Julfa married the English factor in Isfahan. The scope of Armenian commerce, their ability to give credit, and their insurance contracts were among the most sophisticated in Europe or Asia. The Armenians seem have been everywhere, filling gaps in the Eurasian trade network.

If the Armenians helped integrate Eurasian trade, the Jewish trade diaspora did something similar for trans-Atlantic trade, creating links between Europe and the Americas, often across imperial boundaries. The Jewish trade diaspora is probably better known than the others we have discussed, simply because the Jews were deeply embedded in European society. The term “diaspora” has a double meaning here. Its most general and historical meaning refers to the dispersion of the Jews out of what is considered their ancestral homeland (the Land of Israel), creating the communities built by them across the world. Closer to the topic of this book, that definition includes the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal in the 1490s and their dispersion to Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands, England, Brazil, and the Caribbean. As conversos, or former Jews forced to convert to Catholicism, members of Spain’s Jewish diaspora were officially subjects of the Spanish Crown. This left them free to visit the farthest reaches of the Spanish American Empire—places as distant as New Mexico and Manila.

The term “trade diaspora” uses the word to refer to people with a distinct cultural heritage living in colonies located in commercial centers along important trade routes. This is something Jews often did because other economic activities were closed to them. The Jewish trade diaspora emerged because they were already dispersed and were skilled at staying in contact with one another, a skill that could also be used to good effect in trade. Although the Jewish diaspora has dimensions that go beyond the fact that it functioned as a commercial and financial network, it is the commercial aspect that is at the forefront here. The Jewish trade diaspora was so complex by the seventeenth century that it can be seen as two or three distinct, overlapping networks.

The Middle Eastern Jewish network is documented as far back as the tenth century, thanks to the Genizah manuscripts, a huge collection of documents found in Cairo. These papers document every aspect of life in the Jewish community of Cairo and describe its activity as a trade diaspora with a commercial network ranging from Aden, at the entrance to the Red Sea, to Lebanon and North Africa. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a later part of that trade network was active in North African seaports, where its members brokered connections between the trans-Sahara caravan trade and both Christian and Muslim merchants in the Mediterranean.

The fifteenth century saw communities of Jews throughout Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Many members of this medieval Jewish diaspora had lived in Spain and Portugal for centuries. In 1492, when they were formally expelled from Castile and Aragon, they settled in the Ottoman Empire, parts of Italy, North Africa, and Portugal and became known as Sephardic Jews. Only four years later, in 1496, the Jews in Portugal were forced to leave or convert. Several Jewish merchant families converted and stayed in Portugal, becoming “New Christians,” or “Marranos,” a pejorative term often applied to New Christians when they were suspected of being false converts.

Laying the basis for expansion of the Sephardic network beginning in the fifteenth century, wealthy New Christian families in Spain and Portugal, along with the Genoese, provided part of the venture capital for Atlantic exploration, including funds for Columbus’s voyages. Once the Asian trade around Africa was established, the New Christians became an important part of the spice trade between Lisbon and Antwerp, giving them strong connections in the Low Countries.

In the 1560s, just as the Dutch began their war for independence, the Portuguese Inquisition began persecuting these New Christians for supposed backsliding into Judaism. A few well-placed or thoroughly integrated families stayed, but many of these New Christian families followed their business connections and moved to Holland and England, where they often returned to Judaism. For the most part, the Protestant Dutch were happy to accept these New Christian/Jewish businessmen.

The result was a network diaspora of Jews, some in Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Ottoman Empire, and North Africa. They became an interlocking web of extended families and coreligionists that maintained commercial and cultural bridges between the Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, and Muslim parts of both Europe and the Mediterranean. The Sephardic Jewish diaspora expanded again in the seventeenth century. In 1630 the Dutch conquered a large part of the sugar-producing area of Portuguese Brazil, as well as some Caribbean islands off the coast of Spanish Venezuela. The Dutch then encouraged the Sephardic Jews to settle in Brazil and the Caribbean, where they modernized the sugar industry and opened contraband trade with Spain’s American Empire. While nominally Dutch, this Jewish trade diaspora crossed political boundaries and traded with merchants in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonies and with ports in West Africa.

The result was a trans-Atlantic Jewish trade diaspora that transcended imperial and national boundaries and helped integrate the Atlantic economy. As the colonial economy evolved, these New Christian/Sephardic Jews played key roles in emerging trans-Atlantic trades, crossing the boundaries between the colonial empires. By 1700 this Jewish diaspora network connected Brazil, the Caribbean, English North America, and Europe, specializing in the most lucrative Atlantic trades of the seventeenth century: sugar, slaves, gold, emeralds, and diamonds.20

The Jewish and Armenian trade diasporas were similar in many ways; each was committed to a distinct religion, and each relied on complex extended families. They differed in that they had distinctive ways of connecting with the larger commercial world. The Sephardic Jews were relatively sedentary and made extensive use of local, non-Jewish commission agents. The Armenians depended more on long-distance agents in the form of traveling family members who were apprentice merchants.21

East of Melaka, oceanic trade and many local enterprises were dominated by a different diaspora, sometimes referred to as the Chinese of the South Sea, or the Southsea Chinese.22 Thanks to the lack of regulation of Chinese emigration during the Yuan (Mongol) and early Ming dynasties of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and despite the erratic nature of Chinese trade policy, by 1500 every seaport on the South China Sea had a permanent colony of Chinese immigrants.23 This Chinese diaspora included communities lodged in the Philippines, Indonesia, Melaka, and Indochina.24 As a diaspora, it lacked the self-conscious, centralized coordination of the Armenian diaspora. Instead it was a diaspora of small, localized communities that often engaged in business activities other than trade and maintained a variety of relationships with their host societies.

Like the European entry into the Indian Ocean and Indonesia, the Chinese diaspora was almost entirely male. These men settled in port towns, married local women, engaged in small-scale trade, and provided a variety of everyday services ranging from bookbinding to tavern keeping and masonry.25 Small Chinese colonies were already present in Manila before the Spanish took control in 1570 and in Batavia before the Dutch arrived early in the seventeenth century. The Chinese quickly realized that they could profit from working with the European invaders. In Batavia the Dutch depended on Chinese merchants, creditors, and contractors for the construction of Batavia’s fortifications and warehouses. Before long, many of the taxes imposed within Dutch-controlled enclaves like Batavia and Makassar were farmed out on contracts to Chinese businessmen. Under this arrangement, Chinese contractors collected the taxes and kept the revenue, paying the Dutch government a prearranged lump sum and keeping the rest as profit.

One of the important aspects of the Chinese merchant diaspora was its role in the development of the Spanish colony in the Philippines. While administratively Manila was a colony of Spanish Mexico, it was a de facto economic colony of China. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Manila had at most two thousand people defined as Spaniards and as many as twenty thousand Chinese, along with a similar number of Eurasian immigrants. The Chinese community not only controlled the trade between Manila and China but also provided virtually all the service industries in Manila, from bread baking to shipbuilding. Arguably it was a Chinese commercial colony that China chose not to control politically, although on one occasion a Chinese war fleet of five large junks attacked the colony and was barely beaten off. Manila was an uneasy city where ethnic and economic tensions triggered recurrent mass murders of resident Chinese. In each case the colony could not function without Chinese-provided services, and the Chinese population soon recovered.

The Chinese merchants at Manila also traded intermittently with the Japanese. The Japanese record of civil wars and piracy along the coast of the Fujian area of China prompted the Chinese to prohibit direct trade with Japan. By exporting their silver to Portuguese Macao on Portuguese ships, the Japanese “laundered” their silver.26 It officially became Portuguese once it was landed at Macao and could then be sold in China. As Portuguese relations with Japan came unraveled in the early 1600s, the Spanish and the Dutch competed for the Japanese silver trade. In the end, the Dutch were the only Europeans allowed to trade with Japan, and they shared the Japanese silver trade with Chinese merchants.

The Dutch in Batavia were equally dependent on the Southsea Chinese. They tried several times to open direct trade with China but never succeeded. In chapter 8 we will see just how far the Dutch went in trying to set up regular contact with China. Even when China eased its trade regulations, it still insisted that the trade take place on Chinese junks. As a result, most ships bringing Chinese goods to Batavia were Chinese junks owned by members of the Chinese diaspora. Apparently, the harbor at Batavia often contained more Chinese junks than European-style Dutch ships.

Without including the role of the overseas Chinese diaspora, any version of the history of Dutch or Spanish expansion into Southeast Asia seriously under-states the importance of Asian capital and entrepreneurial abilities. As a trade diaspora, the Chinese lacked the centralized coordination of the Armenians, but it did combine a common ethnic and linguistic tradition with effective use of long-distance family and business connections. The Chinese also had an advantage: When the Europeans arrived in the spice islands, the Chinese already controlled the spice trade in the South China Sea. Since they had the ships and a commercial network in place, and European resources were limited, collaboration was the logical solution. This was reinforced by the fact that, except for the Portuguese port at Macau (1557–1999), the Europeans were not allowed to trade in China itself, while the Southsea Chinese had valuable family and business connections in the Guangzhou-Fujian area of China that foreign merchants lacked. As a result, the Dutch and the Spanish had to depend on the Southsea Chinese for exports from China while the Southsea Chinese depended on the Dutch and Spanish for the spices and silver demanded in China. The Spaniards eventually accepted the relationship, but, as we will see in the next chapter, the inability to trade directly with China was a constant source of frustration for the Dutch.

The Dutch East India Company gradually expanded its activities in Southeast Asia, diversifying its exports to Europe and adding new crops such as tobacco and sugar. While this looks like the work of the entrepreneurial Dutch, it also reflects the symbiosis between the Dutch and the Southsea Chinese. As Dutch control gradually spread out from Batavia into rural Java, Chinese investors bought land in neighboring Bantam, brought in slaves, and produced the sugar and tobacco that the Dutch in Batavia wanted to send to Europe.

If we step back and look at the overall pattern of world trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, certain things stand out. China was by far the largest, richest, and most advanced country in the world. Chinese consumers, while they bought large quantities of Indonesian spices and quality Indian cotton cloth, were not attracted to most European exports. As we have seen, by the sixteenth century, China had shifted to a silver-based monetary system. With an economy growing faster than its supply of silver, silver was becoming relatively scarce in China. This caused it to become more valuable in terms of other goods. Thus, imported silver had strong buying power, making the China trade potentially very profitable.

Similar conditions shaped the Indian market, especially once the Mughal Empire was consolidated after 1560. With an estimated 140 million people in 1601, internal peace, improved caravan routes, and the construction of a major new capital city by the emperor Akbar, Mughal India was second only to China as a generator of world trade. As the Mughal government increased its use of silver-based coinage and the Indian economy grew, India, like China, became an attractive market for silver. While Indian consumers had limited interest in European products, they were ready to export quality cotton cloth, high-quality pepper, gemstones, and spices.

In that context, the story of Europe’s relationship with the world is not one of European conquest. It is a story of European entrance into a dynamic Eurasian commercial world. It was a commercial world network that could be dislocated briefly, but it was far bigger and more complex than anything the Portuguese or Dutch could hope to control.