CHAPTER NINE

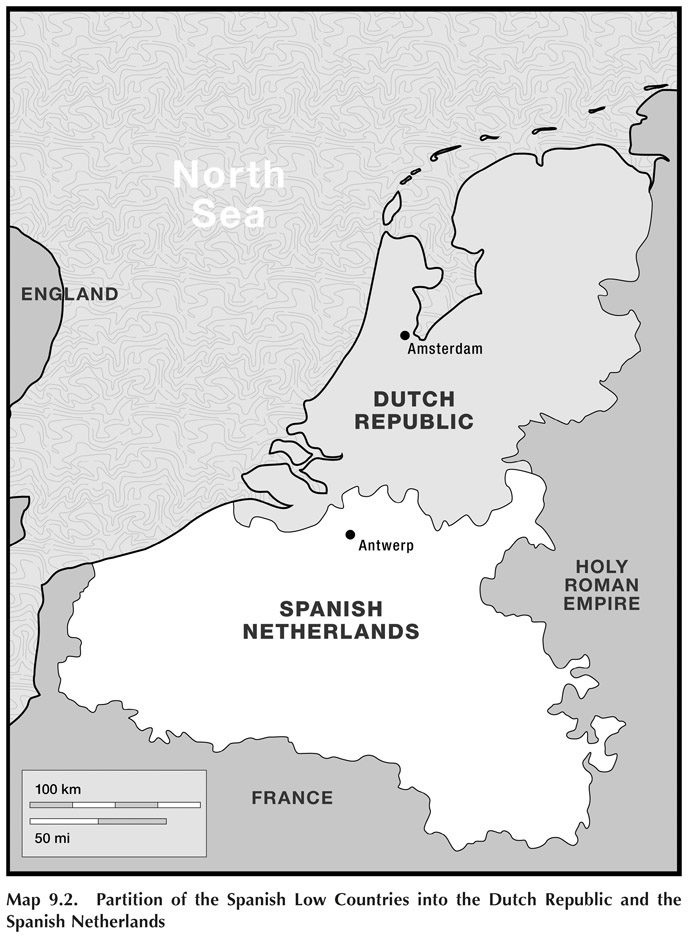

By 1600 the changes of the late sixteenth century had added two new countries to the list of European maritime powers. England was developing a new textile industry and could put a respectable naval force to sea. The Dutch Republic had separated from Spain, taking with it many of the merchants and entrepreneurs who had made Antwerp an economic center. The Dutch economy was growing, and the newly independent Dutch Republic was soon to be the most important commercial country in Europe. Spain and Portugal were still the two most prominent players in European power politics and in world trade, but the Dutch had forced Spain to recognize their existence by agreeing to a truce in the War of Independence. England, meanwhile, had raided Spain’s main naval base at Cadiz and had thwarted two Spanish invasions, in 1588 and 1596.

For most of the sixteenth century, the Spanish and Portuguese had kept the English from using the route around Africa to the East, but by 1600 the Dutch Republic and England were challenging that power. The 1630s saw the Dutch and the English challenging Spanish and Portuguese control over the Africa route and were literally pushing the Portuguese aside. In 1648 the Dutch Republic forced Spain to recognize Dutch independence, reinforcing the Dutch Republic’s dominance in European maritime trade. By 1689 England had taken the lead from the Dutch after defeating them in a series of naval wars, after which England then brought the Dutch William of Orange to England as King William III and co-regent with Queen Mary II. In the process, England surpassed the Dutch as a maritime power.

The search for access to Asian goods began in England in the 1550s, during the reign of Mary I (1553–1558). The first English initiative seems implausible to the modern eye, since it involved getting Asian spices by way of the Arctic Ocean, Moscow, and the Safavid Empire. The proposal shows the lengths to which English merchants were willing to go to get a supply of spices. In 1555 a group of investors formed the Muscovy Company, ostensibly to promote trade between England and Moscow. It planned to reach Asia by sailing north around Scandinavia to the White Sea and the Russian port of Archangel. Merchants and goods would then travel overland almost seven hundred miles to Moscow.

Since the Multani merchants of India were present in Moscow, it might have been possible to buy spices there, but the English project also included sending factors (agents) two thousand miles from Moscow down the Volga River to the Caspian Sea and then to the Safavid Empire—a distance of two thousand miles. For various reasons, including Russian vested interests and clumsy English diplomacy, the czar never gave the English permission to go beyond Moscow. In any case, English merchants appeared in Moscow in the 1560s and developed a substantial trade in hemp, tallow, and rope. The Charter of the Muscovy Company also had a clause giving the company a monopoly on whaling south of Spitsbergen Island, another small source of profit, but the company was never able to develop trade in Asian spices by way of Moscow.

While the Muscovy Company was an implausible way to get access to Asian goods, by the 1570s the English were developing a better connection. In the wake of the Battle of Lepanto (1571), the Ottoman Turks needed to rebuild their artillery. The best large cannons of that era were made of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, and England had important tin mines. The Turks also needed small arms and lead balls for their infantry. The two countries negotiated a formal treaty in 1580, allowing the Turks to buy the war materiel they wanted, while the English took home currants, indigo, olive oil, wine, alum, and raw cotton. The treaty of 1580 also allowed the English to establish permanent trading posts or factories in Constantinople (1583) and Smyrna (1620). The Levant Company then set up its eastern headquarters in Aleppo (1586),1 a major emporium for the caravan trade on the route from the Persian Gulf and the Safavid Empire to the Mediterranean port of Iskenderun. To take advantage of the treaty with the Ottomans, English trading companies active in the Eastern Mediterranean worked together to create a larger version of the Levant Company in 1592.

The Levant Company did not engage in trade itself, but provided offices, port facilities, and brokerage services in the Eastern Mediterranean for its merchant members, with agencies as far inland as Isfahan. The Levant Company ships exported both local Turkish products, like dried fruit and alum, and Asian goods that had crossed the Ottoman Empire to its Mediterranean ports. The Levant Company also assisted its members by transferring silver from Europe to Aleppo for merchants engaged in trade farther east, an illustration of the movement of silver eastward to compensate for Europe’s lack of salable products. While the English bought silk produced in the area around Aleppo, they also bought the Persian and Chinese silk that had reached the Aleppo market by caravan. In 1617 the shah created a state monopoly governing the Safavid silk trade and appointed Armenians to administer it. As they negotiated with the Armenians for Persian silk, the English developed Armenian contacts that allowed them to do business with Armenians in Surat or Manila.

The Armenians preferred to export Persian silk through Ottoman Aleppo because it gave them access to customers who paid with American silver that had come by way of Europe. That silver stimulated the Safavid economy and let its merchants buy imports from India. As the English economy developed its wool textile industry under Elizabeth I, the Levant Company exported increasing quantities of English wool textiles to Ottoman markets. The Ottomans, like the other “Gunpowder Empires,” were always ready to buy European weapons, and the English sold them artillery, muskets, and military supplies as well as silver to satisfy England’s growing appetite for Middle Eastern and Asian products. The bottom line, however, is that, like the Portuguese and the Dutch, the English could not sell enough European commodities to pay for their imports from the Middle East and regularly brought large quantities of silver from Europe to pay for the goods they bought.

As the first Dutch and English ships arrived in the Indian Ocean in the 1590s, they headed first for Java and the Maluku Islands in search of spices for markets in London and Amsterdam. Unfortunately, several shiploads of spices returning at the same time sent European prices down dramatically. That, and experience in the East Indies, persuaded the businessmen of both England and the Dutch Republic to set up large joint stock companies that could control European marketing and guarantee an adequate supply of the most important spices. The Dutch maintained their interest in Java and the East Indies, while the English soon shifted their emphasis to India and the Mughal Empire. Given their more limited resources (see below), the English established themselves within a powerful and well-organized empire, while the Dutch preferred to set up an independent stronghold away from any of the stronger Asian states. This had advantages for the English since, at much less expense than incurred by the Dutch, the Mughal Empire provided the English with a degree of protection. The Mughals regulated the behavior of England’s European competition and, with their base at Surat, gave the English access to a market second only to that of China.

Supplying a national market at home, the unprecedented length of supply lines, the number of ships needed, and the complexities of extracting the right commodities from the Asian commercial economy required private enterprise on an unprecedented scale. The financial innovation that made this possible was the joint stock company. Forerunner of the modern corporation, the English and Dutch East India Companies merit a certain amount of attention.

As we suggested earlier, most businesses in early modern Europe were partnerships. Typically, most of the partners were members of the same extended family, allowing the family to maintain control of the business. A partner, however, owned his piece of a company personally. He could sell it back to the business, but he could not sell it to anyone else without permission from the other partners. Historically, the partnership form of business allowed merchants to accumulate capital to pay for new ships and cargoes, and to spread any losses among all the partners, but it was limited to the resources available within a family-based commercial network.

A joint stock company raised capital without having to depend on family networks, relying instead on the more impersonal sale of standardized shares. The men organizing the company issued hundreds, even thousands, of shares, each with the same modest face value. As a document, the share simply said that whoever possessed the share was entitled to a portion of company profit. Since each share had a small face value, thousands of people with moderate incomes could afford to buy them. The additional attraction for the small investor was its flexibility as an investment. If a shareholder ran short of funds, he could sell some of his shares on the stock exchange. If the company was doing well, potential buyers might even pay more than the face value of the share. By selling shares to thousands of shareholders spread throughout middle- and upper-class society, the promoters tapped huge amounts of capital, even though the participation by individual shareholders could be quite small.

The joint stock company was not a new idea in 1600. It had been used in England for smaller enterprises such as the Muscovy Company and the Virginia Company, but never on the scale projected for either the English or the Dutch East India Company. The English East India Company was put together by a group of wealthy promoters who obtained the charter and arranged to sell the shares, promising implausible rates of return. Technically, the shareholders elected the managers. In practice, since few shareholders attended shareholder meetings, an inner cadre of major investors, who often selected themselves to run the company, decided how to invest the capital. Most shareholders were effectively separate from management.

The Dutch East India Company was also a joint stock company but had a distinctive, politically driven organization. The central office was run by a seventeen-man board of directors. Each of the Dutch Republic’s six major seaports had its own chamber, with its own elected board. The six chambers each chose members of the Board of Seventeen according to the amount of capital they raised. This gave Amsterdam eight of the seventeen seats and virtual control of the board that ran the company. The company issued a limited amount of “preferred” stock to a few dozen major participants and thousands of shares of ordinary stock that could be sold on the stock market.

While the actual amounts of capital raised by these two countries are just numbers to a modern observer, the scope of these projects was enormous for their time and place. The initial sale of shares by the English East India Company yielded 63,000 pounds sterling. This was the equivalent of 20 percent of Queen Elizabeth I’s annual revenue from the entire country of England. That makes it an impressive project by English standards, but it seems small next to the Dutch company. The Dutch East India Company raised 550,000 English pounds, which is eight and half times the English figure and close to two years of Elizabeth’s annual revenue. Chartered as joint stock companies, each East India Company enjoyed a monopoly on the sale of spices from Asia in its home country. Unlike most chartered companies, however, the Dutch and English East India Companies were also granted the right to act as governments in their respective empires.

Compared with its Dutch counterpart, the English company had relatively limited capital reserves. The English East India Company put most of its capital into outfitting ships and providing their captains with the silver and European products that would interest Asian customers. Rather than invest in infrastructure, the English EIC seems to have assumed that its ships and captains could participate in Asian trade without much protection beyond a few ships’ guns.

During the EIC’s first years, its ships and agents were simply new participants in Asian trade. When an English ship arrived in port looking for cargo, the captain and his secretary would go ashore in search of wholesale markets and landowners with unsold export commodities. Over time, the English captains routinely sought one another out and exchanged information on navigation, local politics, and economic conditions.2 The company’s first voyages went directly to Bantam, on the western end of the island of Java, for pepper; but by 1608 their emphasis had shifted to the seaport and emporium at Surat, which became England’s main base and first port of call.

The company soon decided that having each captain act as a purchasing agent was inefficient and began to establish factors, or purchasing agents, who resided all year in eastern ports. Their job was to buy goods when prices were low and store them until a company ship arrived. In places where ships called frequently, the factor was given a staff of four or five assistants. The English EIC seems to have had no consistent policy regarding the fortification of these trading posts. Some factors asked for fortification and were ignored. Others were given orders to build a fort and ignored them. In at least one case, the local factor got tired of maintaining his fort and simply closed it down, paid off the mercenaries in the garrison, and sent them away.3

Once the English had been in the Indian Ocean long enough to be familiar with military and commercial conditions in the area, they began to exploit Portugal’s weakening position in the western half of the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese network between India and East Africa was in financial trouble. Profits and revenues were falling as Portuguese officials traded outside the royal monopoly, sometimes profiting from the shipment of spices to the Middle East, even though in their official capacity they were supposed to be preventing that kind of trade. Asian merchants revived the old routes through the Middle East, a trend reinforced by trade-friendly mainland governments. The English soon discovered that the Mughal government in India was willing to allow them to trade in Indian ports and, in fact, regarded the English as a useful counterweight to the Portuguese and their periodic attacks on Muslim pilgrimage ships.

The English East India Company also gave its agents wide latitude for participating in Asia’s local trade. At first this was on a semi-licit ad hoc basis, but it was formally legalized after 1660. The result was a rich source of information, both official and private, that allowed the company to function more efficiently.4 In this way the English gained hands-on knowledge of the local individuals and family networks that moved goods around. This in turn allowed the company to shift away from its initial emphasis on spices to a range of more basic goods that could be sold to the growing middle-income markets of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe.

Over the course of the seventeenth century, the English EIC tried to penetrate the lucrative Safavid-Persian silk trade. The main obstacle to an English EIC role in the Safavid silk trade was neither the Dutch nor the Portuguese but English merchants who belonged to the English Levant Company. The Levant Company had been established in Mediterranean ports and markets of the Ottoman Empire for several years before the English East India Company reached the Indian Ocean shores of the Safavid Empire. Through its Asian headquarters in Aleppo, Levant Company merchants were buying silk from the Safavid Empire with the help of Armenians from New Julfa. They sent the goods by caravan the short distance to Iskenderun on the Mediterranean coast. There the goods were loaded on the ships of Levant Company merchants and taken to England.

The English East India Company tried to negotiate with these same Armenians for an agreement that would divert silk to their ships at Bandar Abbas, at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. From there company ships would carry the silk around Africa to Europe. The Armenians pointed out that they had a variety of outlets for their silk and saw no point in committing to a monopoly with the English East India Company. Furthermore, they did not believe the English EIC had the capital needed to finance the silk trade on the scale the Armenians required.

Until the EIC was revised and recapitalized in the 1660s, it depended on short-term loans and commercial credit from Gujarati Indian merchants. Later, even when the English EIC had more capital to work with, they still depended on local merchants for commercial credit. They also maintained a close relationship with the Armenian community in India. The EIC borrowed funds from the Armenians as short-term loans and arranged to use the Armenian merchants’ long-distance courier service. This allowed the English to send correspondence overland through the Middle East to the Mediterranean and then to England. This way, the home office knew what was coming on the ships en route long before they arrived and could adjust the markets to maximize profits.

The Armenians proved to be valuable allies. They had been a trusted part of the Indian commercial networks for at least two centuries. They not only provided the English with credit but also helped the English establish a business relationship with the Gujarati merchants and helped them get silver from Manila. Provided annually by the shipload from Mexico, silver in Manila was cheaper than silver bought in Europe and then shipped to the Far East.

Like the Portuguese and the Dutch, the English EIC could not find enough in the way of European products to pay for the Eastern and Middle Eastern goods they wanted to take back to England. As a result, the English East India Company sent large quantities of silver to its agents in India and elsewhere.5 Despite complaints from economists of the seventeenth century, who equated national wealth with the amount of bullion within the country, the English EIC pointed out that to buy goods in Asia, the company had to buy silver that came from America and reexport it to Asia.6 Through the 1630s, English EIC ships bound for India often carried nothing but the silver they needed for operating in Asian markets.7

The English EIC was always buying silver for its trade with India and China, and in the first half of the seventeenth century the company bought it on the European market. The English EIC also knew that silver was relatively cheap in Manila, but neither the Dutch nor the English were allowed to trade there. The English got around this prohibition by turning to their Armenian colleagues in India.8

The Armenians had been able to establish themselves in Manila because they were useful to the Spaniards in many kinds of transactions. The Armenians operated their own ships and flew a distinctive Armenian flag, and the Spaniards treated them as subjects of an independent country. Secretly working on behalf of the English, the Armenians took English-owned Indian cloth and other products to Manila and traded them for American silver. The Armenians then delivered the silver to the English East India Company offices at Chennai, Mumbai, or Kolkata. In the process, the Armenians made a good profit and the English got silver more cheaply than if they bought it in Europe.

The English East India Company, unlike its Dutch counterpart, maintained only modest military assets. Beyond a few small forts with garrisons of mercenaries, the company did not maintain a significant land-based military until the 1660s, while the Dutch maintained a colonial army of ten thousand troops. At sea, the EIC maintained a minimal navy; in 1623 the English EIC had exactly two warships based in Mumbai, while the Dutch had sixty-six ships active in Asia.9 The first fortified English trading post was built in Surat in 1619, after careful negotiations with the Mughal government. The next, in Chennai (Madras), was not built until twenty years later.

Meanwhile, the company got caught up in English politics. The 1640s in England saw civil war, the execution of the king, and the beginnings of a military dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell. In that chaotic environment a group of speculators tried to start a second English East India Company that would exploit areas the first East India Company was ignoring (see chapter 6). It accomplished little except for two abortive attempts to colonize Madagascar in the 1640s.

As late as 1650 the English EIC had only twenty-three factories, most of them in India, and only two had serious fortifications. The entire English East India Company had only ninety paid employees in India, hardly an army of conquest. The EIC’s Asian headquarters in Surat were only there by agreement with the government of the Mughal Empire. The English got the nearby island of Mumbai and its decrepit fortress in 1661 but were slow to develop it. When the English kept insisting on more privileges, the Mughal emperor refused and promptly sent the Mughal navy to force the Mumbai fortress to surrender.

By the 1680s, however, the English East India Company was wealthier and more profitable than its Dutch competitor. Until about 1740 the English EIC was focused primarily on the commercial and financial opportunities inherent in the Indian economy and its “lively market in commercial, fiscal and military opportunities.”10 Its factors not only were active in private trade but also mobilized exports from India to Europe through partnerships with Indian merchants who were prominent in the intra-Asian “country trade,” transporting Asian commodities from one part of the region to another.

The prosperity that came to the Portuguese with the Japanese silver trade lasted until the 1630s but then proved to be very fragile.11 The Portuguese merchants had borrowed large amounts of money from Japanese merchants and bankers. The shogun saw this as making the Japanese business community vulnerable to Portuguese preferences. The shogun also suspected that, despite a Japanese prohibition on Christian missionaries in Japan, the Portuguese were protecting Christian missionaries. Not surprisingly, the Dutch did what they could to reinforce that suspicion. This prompted the Japanese authorities to expel all Portuguese from the country in 1639. In one stroke they destroyed the apparent prosperity of Portuguese Asia and left the Dutch as Japan’s sole European contact.

The loss of the Japanese silver trade, along with other setbacks, reduced the Portuguese trade diaspora to a few small ports. The problem worsened with Portugal’s declaration of independence from Spain. This war for independence (1640–1668) reduced the flow of men and materials to Asia and made it difficult to trade with Spanish-controlled Manila. During the second half of the 1600s, the Portuguese lost most of their trading posts in East Africa. The Sultanate of Oman, using the same tactics the Portuguese used to build its own trading empire, peeled off one Portuguese port after another, starting in 1650 with Muscat on the Persian Gulf.12 The low point for Portugal came when Oman captured the Portuguese port and massive fortifications at Mombasa in 1698.

Meanwhile, the Dutch War of Independence dragged on for many years (1568–1609, 1621–1648). Spain had been forced to accept a truce in 1609, but it stubbornly renewed the war when the truce ran out in 1621. For practical purposes, the Dutch were not only independent by 1585 but also remarkably rich. The Spanish Low Countries had been one of the wealthiest and most advanced parts of Europe. When the seventeen provinces of the Spanish Low Countries were divided into the Dutch north and the Spanish-ruled south, the political situation in Europe presented the new Dutch Republic with a unique opportunity. Most of the trade that had made Antwerp wealthy moved north to the new Dutch Republic.

This was possible because of the complicated politics of the Habsburg Empire in Europe. At the end of the fifteenth century, the seventeen provinces of the Spanish Low Countries had been ruled by the Habsburg family in Vienna. They became part of the Spanish Habsburg Empire at the beginning of the sixteenth century and were one of the richest parts of Charles V’s Empire. Europe’s sixteenth-century economic expansion was concentrated in the Low Countries, and the coordinating center for that economic expansion was Antwerp, the largest city in the seventeen provinces.

Long before Dutch independence, Antwerp and Amsterdam, both cities in the Low Countries, had developed an economic partnership. The physical volume of trade passing through Antwerp had outgrown the city’s modest harbor, and merchants who handled bulky commodities had taken to sending cargoes of wheat, barley, lumber, and building stone to Amsterdam, which had better dock and storage facilities. Antwerp-based shipping companies and merchants that used Amsterdam as a kind of out-port found it convenient to have branch offices in Amsterdam.

When the Portuguese started bringing spices around Africa to Europe, they discovered they had to rely on the Flemish, Dutch, and German merchants of Antwerp to distribute the spices throughout Europe. The Portuguese had trouble finding enough experienced merchants and financiers in Portugal to staff the Estado da India, and before the Dutch Revolution they routinely recruited Dutch and Flemish merchants to positions in their Asian trade diaspora. When the Dutch Revolution got seriously under way, two things happened to help the rebels.

They were able to block access to Antwerp’s harbor, which crippled that city’s foreign trade. Many of the Dutch and Flemish family businesses that had their headquarters in Antwerp and branches in Amsterdam simply moved their headquarters to their offices in Amsterdam, leaving a small office in Antwerp.13 In this way they quietly moved most of the commerce that had made Antwerp prosperous to Amsterdam and the new Dutch Republic.

The second important development involved the Dutch and Flemish employees of the Portuguese Estado da India who had come from the seven provinces of the now independent Dutch Republic. They had to decide between their loyalty to their home province and loyalty to their Portuguese employers. This became even more difficult in 1580, when Philip II took over the entire Portuguese Empire. Dutch and Flemish employees of Portugal suddenly found themselves working for the Spanish king who was trying to defeat the new Dutch Republic, which contained their hometowns and home provinces. Many of them quietly resigned their jobs in the Portuguese empire and joined their family firms in Amsterdam. Their knowledge of the inner workings of the Portuguese empire proved invaluable when the Dutch reached the Indian Ocean. The most famous example is Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563–1611), who spent several years as secretary to the Portuguese viceroy in Goa. Once in Amsterdam, van Linschoten published top-secret Portuguese maps of Asian ports and commercial guides, making them available to the Dutch commercial world.14

In 1596 a sizable Dutch fleet arrived at a small port on the northwest shore of Java, a port destined to become the port city of Batavia. Variously called Sunda Kelapa or Jayakarta, the Dutch hoped to influence local authorities and negotiate a treaty that would allow them to trade there on a regular basis. Located near the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, the little port was well positioned to support trade connections that ranged from Japan to Sri Lanka.

As we have seen, Dutch and English experience in the spice trade during the 1590s showed that it was easy to glut the European market for spices; too many independent participants would drive down the price of spices in Europe. The English solution came in 1600, when they founded the English East India Company. The Dutch followed in 1602, consolidating their various East India merchants into the Dutch East India Company, with several times more capital than its English counterpart.15 Both companies had a monopoly on sales within their respective countries. Both were joint stock companies, and although neither was a modern corporation, they were able to raise more capital than a traditional family-based partnership.

By 1611 the Dutch had established a route from Europe that ended in Batavia, a route they would use for over a century. As they passed the Cape of Good Hope, instead of sailing north along the African coast, the Dutch sailed east across the open Indian Ocean, following the prevailing winds at latitude forty degrees south. When the captain and the navigator agreed that they were south of the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, the captain turned north, aiming for the strait and nearby Batavia.

As they crossed the southern Indian Ocean, Dutch ships sometimes sailed far enough east to encounter Australia, and by 1627 various Dutch encounters with Australia allowed them to map its west coast. This southern route had the advantage that ships outbound from Holland avoided the Portuguese, who sailed north along the east coast of Africa, and the English, who sailed up the east coast of Madagascar. Since the Dutch were at war with either the Portuguese or the English through much of the seventeenth century, this southern route offered serious advantages.

The disadvantage was that it involved an open ocean voyage of almost eight thousand miles, with few places to get fresh water and food. A modern map implies that ships could have stopped on the west coast of Australia, but those that did had consistently violent encounters with the Australian Aborigines. It has been suggested that hostility to Europeans reflected awareness among Aborigines that Europeans brought deadly diseases. Whatever the reason for Aborigines’ hostility toward the Dutch in the seventeenth century, it did not, at that time, stem from earlier contact with foreign visitors and the diseases they might carry.16

Once the Dutch were committed to using the southern route across the Indian Ocean, the port of Jayakarta was an obvious target for a Dutch take-over. The town was an autonomous dependency of the Sultanate of Bantam, and the sultan had earlier prevented the Portuguese from seizing it. Both the Dutch and the English wanted Jayakarta, but the sultan resisted both. In 1619 the Dutch captured the port, but only after a complicated battle against both the local government and the English, during which the town was burned to the ground. The Dutch renamed it Batavia and began building a fort, headquarters, and shipyard. Over the next twenty years they built an elaborate trade system that reached north to Japan and west to India and Sri Lanka.

Taking advantage of its capital resources, the Dutch East India Company set about building a huge enterprise, at the heart of which was a well-fortified Batavia, with its shipyards, warehouses, and company bureaucracy. Batavia was, in turn, the coordinating center for a network of well-staffed and fortified purchasing factories or agencies.

In its first years the Dutch EIC allowed its individual ship captains to negotiate for cargo, a strategy that forced it to invest in ships, manpower, and multiple negotiations, but did not require maintaining armed warships and forts. Similar to the Portuguese approach, this policy kept overhead down, but it meant dealing directly and repeatedly with indigenous markets and was vulnerable to changes in supply, price, and profits.

Once the Dutch East India Company was in place, with ample capital to work with, the Dutch proceeded to build a large company, one with the resources to sustain long-term decisions despite short-term costs. They invested heavily in a company-supported army and navy and coerced producers into selling only to the Dutch East India Company. By investing in fortified ports and maintaining a substantial company army and navy, the Dutch incurred higher fixed costs than the Portuguese or English but assured themselves of high and steady profits in Amsterdam.

This allowed the company to calculate potential risks and profits more accurately than if they depended on the commercial skills of individual shipmasters as they visited different ports. The system made the products it exported to Europe slightly more expensive because of higher overhead costs, but it produced more stable profits from year to year.17

The Dutch also tried to regulate the cost of acquiring spices. In contrast to the Portuguese network, where much of its trading was done by individual Portuguese traders, the Dutch East India Company operated through a bureaucracy of salaried accountants, bookkeepers, and purchasing agents. Ship captains and factors, as well as office staff, were paid salaries and not allowed to trade independently. By 1700 this bureaucracy employed about fifteen thousand people and was slow to respond to changing market conditions.

In 1650 Batavia was the biggest and richest “European” city in seventeenth-century Asia. In 1700 it was the hub from which spoke-like trade routes radiated outward to Sri Lanka, India’s Coromandel Coast, the Tuangoo Kingdom (formerly Burma, now Myanmar), Melaka, Makassar, the Maluku Islands, Siam, Formosa, the Ryukyus, and Japan.

While it was a success in terms of Dutch objectives, Batavia also demonstrates the degree to which even the well-capitalized Dutch depended on the collaboration of the Asian world around them. The Chinese community, already resident in Batavia when the Dutch took over, provided the contractors, laborers, and capital to build the Dutch fort at Batavia. The Dutch also depended on resident Southsea Chinese, their ships, and their relatives in China for much of their Chinese trade.

The Dutch EIC was primarily interested in having a stable supply of spices and other Asian goods reach their European markets at profitable prices. Initially, this was a problem of controlling the trade routes, but increasingly Dutch policy shifted to control of actual production. This policy focused first on the production of spices, especially cloves and cardamom, commodities the Dutch forced the growers to sell exclusively to the Dutch EIR. In some cases, the Dutch systematically destroyed the trees of owners who tried to escape the Dutch monopoly.

![Figure 9.1. Asian and European Ships Anchored at Batavia. (Hendrick Dubbels [painted ca 1650]; courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)](../Images/chpt_fig_036.jpg)

By the eighteenth century, the Dutch were developing sugar plantations on Java and cinnamon plantations on Sri Lanka. On Java, many of the sugar plantations were actually in nearby Bantam and operated by Chinese owners and investors. Plantation agriculture brought a new demand for slaves analogous to that of the Atlantic world.

The Indian Ocean slave trade was different from its Atlantic counterpart because, although some of the slaves came from Africa, most of them came from other countries bordering the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. As we saw in chapter 8, the Indian Ocean slave trade was centuries old and was part of the trade portfolios of merchants from a number of Indian Ocean merchant communities. In 1700 the demand for plantation labor was relatively new, and slavery in southern and southeastern Asia general was an urban phenomenon found in households rather than in the fields.

As the Dutch East India Company expanded its plantations, it also took part in the slave trade, but the Dutch (and other European) participation was a small part of the Asian slave trade. In the two centuries from 1600 to 1799 the Dutch brought between 65,000 and 90,000 slaves to Batavia and Cape Town, suggesting a modest 325 to 450 a year.18 Although the Indian Ocean slave trade included many Africans, most slaves came from a variety of Asian societies. As a result, it fostered fewer racist stereotypes than the Atlantic slave trade.

One of the continuing frustrations for the Dutch was their inability to trade directly with the Chinese. They spent years negotiating unsuccessfully with the Chinese government and with Chinese smugglers and pirates on the Fujian coast. In 1622, in hopes of gaining at least indirect access to China, the Dutch agreed to help China suppress piracy in the South China Sea in return for permission to build a fort on Taiwan. Fort Zeelandia served as a colonial base on Taiwan for forty years, functioning as a base for surreptitious trade with mainland China.19 Carried on by Chinese shippers, it was relatively easy to maintain a black market in the waning days of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) but was more dangerous under the new Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Finally, in 1662, a well-armed Chinese fleet and army forced the Dutch to surrender and leave Taiwan.

Between 1602 and 1640, as the Dutch built up their base in Batavia and created a network of factories, profits lagged behind expectations. Behind the scenes, the Dutch, like the Portuguese and the English, had difficulty paying for the goods they wanted to send to Europe. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch tried to compensate for this problem with profits from the intra-Asian trade, but those returns never paid for more than a part of the cargoes they sent home to Amsterdam. The remainder had to be paid for with silver.

Merchants could always buy Chinese exports with silver. Silver reached the Asian market from Europe, Mexico, and Japan. Silver brought from Europe was the most expensive, since it had passed through the hands of several middlemen as it traveled from Mexico to Europe, then to the Mediterranean, then through the Middle Eastern economies, before reaching the South China Sea. Alternatively, modest amounts traveled around Africa in Portuguese ship to Goa before reaching the Chinese market. American silver, brought directly from Mexico by the Manila galleons, was much cheaper, but Spain would not allow the Dutch or the English to trade at Manila. That is why the English relationship with the Armenians was so important to the English East India Company—the Armenians were allowed into Manila and could buy silver there. Japanese silver was even less expensive, since Japan was much closer to the Chinese market and the Japanese mines were less expensive to operate than the American ones. From the late sixteenth century until 1639, Portugal was the only European country allowed to export Japanese silver for sale in China. The Japanese expelled the Portuguese in 1639 because they were convinced the Portuguese had encouraged a peasant revolt in 1637. They were also suspected of protecting missionaries the government had tried to expel. Because the Dutch had helped the Japanese government suppress the revolt, they were allowed into the silver trade.20

The Dutch eagerly picked up a large part of that very profitable trade, since Japanese silver was much cheaper than silver brought from Europe. While the Chinese also imported the spices of southeastern Asia and Indian cottons, silver was the one commodity Europeans could always trade for Chinese exports.

Access to Japanese silver, control of Melaka, control of the cinnamon of Sri Lanka, and the capture of Makassar near the spice-producing islands greatly improved the situation of the Dutch East India Company. Subsequently, the Dutch seized Colombo (1656) from the Portuguese and then the rest of Sri Lanka (1658), giving them control of the main source of cinnamon in the Indian Ocean. In 1662 the Dutch and English moved in on the Portuguese ports along the coast of India and came close to capturing Goa. In 1667 the Dutch also captured the city of Makassar on the island of Sulawesi. Until then it had been a major commercial center for the surrounding Spice Islands and had collaborated closely with the Portuguese. Once the Dutch were in control, they were in a much better place to control the supply of spices sent to the Indian Ocean markets. It is important to note that Dutch success came largely at the expense of the Portuguese, not through control of additional Asian territory.

In the major emporia ports that serviced the trans–Indian Ocean trade, the Dutch (and the English) used established local brokers for the purchase of exports. In lesser centers the Dutch did as other merchant communities had done and set up resident factors. The scale of these Dutch factories is suggested by the Dutch purchasing agency in Ava, the capital of the Taungoo Kingdom (in what is now Burma/Myanmar).21 Its staff consisted of fourteen employees: three senior merchants, two junior merchants, and nine assistants and sailors.22 All were established residents, and some of them had long-term local partners who bore them Dutch-Burmese children. Although these women were wives in the eyes of custom and local law, the government in Ava was reluctant to let them leave the country, and at least one chief factor chose to stay in Ava for more than thirty years rather than leave his family.23 The assertion that the Dutch East India Company was hampered by a bloated bureaucracy gets some support from the fact that while the Dutch agency in Ava had a staff of fifteen, a comparable English East India Company factory of 1650 got by with four or five people.

Throughout the Dutch network in southeastern Asia, the Dutch East India Company owed a great deal to the Chinese workers and entrepreneurs found in every significant seaport.24 The development of the plantations on Java, often attributed to Dutch initiative, illustrates another way in which Southsea Chinese capital and management reinforced the Dutch economic empire. The symbiosis between the Southsea Chinese and the Dutch makes the image of European control somewhat shadowy.

Sugar, for example, was one of Batavia’s most important exports in 1700, but it was soon replaced by coffee. In 1721 Java produced two thousand pounds of coffee. Only fifteen years later, in 1736, Java exported nine million pounds of coffee.25 As with many other businesses, a large share of the plantation crops exported from Batavia were produced by Chinese capital on Chinese-owned plantations.

In the end, the Dutch (and other Europeans) made up only a small part of the Asian commercial world. They could influence the matrix of local markets, small-scale traders, indigenous wholesale merchants, and local ship owners, but at the same time they had to conform to local practice. The best examples of European dependence on indigenous Asian commerce can be seen in the fact that neither the Dutch, the English, nor the Spanish were able to trade directly with China. Both relied on the Fujianese and Southsea Chinese to bring them the silks, porcelains, and gold that dominated China’s export trade. While Fort Zeelandia on Taiwan allowed the Dutch to get closer to China’s mainland markets, that channel was lost in 1662.

By 1700 the Dutch East India Company was beginning to lose its momentum. Having internalized the cost of defense and administration, the company’s overhead remained high even though profits were declining. They continued to concentrate on marketing essentially the same commodities even though by the eighteenth century, other suppliers were increasing the supply and driving down the market price. Thus, even though the volume of sales remained the same, both profit per unit and the rate of return to invested capital declined.

The rate of return was declining, but administrative costs were not. Profits had leveled off at the end of the 1600s, when the Dutch East India Company had thirteen thousand employees. The profit was not much different in 1750, when the company was supporting twenty thousand people, including a sizable navy and an army of ten thousand soldiers, plus dockyard workers and a bookkeeping staff of hundreds.26 The Dutch trading empire continued to operate until its bankruptcy in the late eighteenth century; it failed because of growing overhead and declining revenues from products that no longer commanded high prices. Their English competitor survived into the nineteenth century because it invested much less in commercial infrastructure and could respond to the flow of fresh market data, thanks to the activities of their factors, operating as private merchants.