CHAPTER ELEVEN

Beginning about 1450, the first group of several million people left Europe for distant and alien parts of the world (see chapter 1). These ventures were organized and promoted by Portuguese and Castilian elites and, later, by Dutch and English merchants. The men who organized and funded the early explorations risked their capital in hopes of a good return to their investments, but few of them personally risked the yearlong trip from Lisbon to Goa or Amsterdam to Batavia. Once venture capital had been accumulated and initial expeditions had established safe destinations, the promoters set out to recruit people who were able to trade or ready to fight.

Depending on the destination, would-be colonists were offered a range of opportunities that included free farmland, indentured service with the promise of land and freedom after service, careers as sailors or mercenary soldiers, freedom from religious persecution, and/or positions as brokers or factors in the East Indies. Some recruits were simply escaping debt or legal prosecution. Typically, recruiters exaggerated the opportunities at the end of the voyage and understated the risks implicit in sailing ten thousand miles in search of a better life. By 1750, commercial and governmental promoters had recruited almost four million people, mostly men, for these overseas projects.

When this migration started in the fifteenth century, everyone was hoping to reach the Spice Islands. Columbus’s accidental discovery of the Americas changed that goal forever—and diverted half of Europe’s early modern migration to the Americas. The other half of the migrants leaving Europe sailed around Africa to Asia, where they met societies as sophisticated about trade and military power as their own.

In the Americas the Europeans encountered the Aztec and Inca Empires, as well as vast areas peopled by Native Americans living in small, autonomous societies. Some of those communities, like the Iroquois, maintained alliances with neighboring tribes, but for Native Americans living outside of the major empires, political organization did not extend beyond the local community. Europeans, wherever they went, brought European culture, technology, traditions, and attitudes as they searched for ways to get rich, as wealth was defined in European culture. Unknowingly, they also brought a range of European diseases to which the Native Americans had no immunities.

Shaped by the devastating effect of European diseases and by differences in technology, European settlement in the Americas produced three distinct narratives. In all three, Europeans soon learned to subordinate or push aside the Native American populations in order to develop exports that brought profits to Europeans.

In 1519 Fernando “Hernán” Cortés invaded Mexico with only a few hundred men. After a long siege, Cortés broke into Tenochtitlán and captured the surviving Aztec leaders. Once inside the city, it was clear that Cortés’s victory had been made possible by a smallpox epidemic. Ten years later the Pizarro brothers had similar grim luck in the Inca Empire, where they were preceded by an epidemic that killed the emperor and triggered a civil war. The Spaniards, with the aid of Indian allies, captured the Inca capital, Cusco (see chapter 4), and briefly used the survivors of the royal family as a facade for Spanish rule.

In both Mexico and Peru, the victorious Spaniards had to create at least a veneer of political authority over millions of Aztec and Inca subjects. They managed this with occasional use of force combined with a long list of collaborative compromises that recognized Native American leaders and allowed indigenous towns to keep control over their own internal affairs.1 The resultant Spanish American Empire was geographically huge, but it was locked into a massive demographic decline through most of the sixteenth century. The scale of that decline is suggested by the fact that the lowest estimate for the pre-Hispanic population of Mexico is 10 million inhabitants, while by 1620 the population was only 1.2 million.2 Meanwhile, when the Mexican and Peruvian silver mines came into full production in 1560, the thousands of tons of silver produced by these mines made Mexico City the financial center of the world. Mexican and Peruvian silver also provided Europe with a commodity that was in great demand in China and India (see chapters 8 and 9).

Elsewhere in the Americas, the European invaders dispersed to locations that ranged from southern Brazil to the Caribbean, Virginia, New York, Massachusetts, and the Saint Lawrence River Valley (chapter 6). Arriving in small numbers and poorly supplied, these immigrants encountered equally modest communities of Native Americans. The latter typically were suspicious, wary, curious, and often generous. If European settlements survived their first years in America, it was thanks to Native American willingness to trade and to their traditions of hospitality.

Settlements in the tropical coasts and islands of Atlantic America produced a second American narrative of expansion. There, European settlement created a unique new society, one that emphasized export-oriented agriculture, primarily sugar, but also tobacco, coffee, and cacao. In those tropical settings the Native Americans fled from European contact, were enslaved, or died of European diseases. As disease killed off the indigenous population, Europeans created distinctive plantation societies.

What was new, and would create a long-lived legacy of racism and inequality, was the scale of Atlantic America’s plantation society and therefore of African slavery. The plantation enterprise was built upon the lives and work of more than twelve million Africans, who were sold into slavery by African merchants and rulers and brought to America by European slave traders in miserably crowded European slave ships. Of the twelve million Africans taken from Africa as slaves, ten million lived to work on plantations. The other two million died while crossing the Atlantic.

While the Caribbean plantations depended on millions of African slaves, they also benefitted from virtually free Native American land, European markets, and European capital. Plantations became so specialized that they did not grow their own food, importing it instead from Pennsylvania, New York, and New England, creating a West Atlantic sub-economy that linked the English American colonies with the plantation colonies of the Caribbean. By 1750 this formula for plantation agriculture had spread across the Caribbean and into the North American south, where it was used as far north as the Chesapeake Bay.

The third narrative describes another kind of colonial American society, one that was taking shape in the northern parts of the English-controlled Atlantic coast. Even before sustained European settlement began in 1607, many Native American communities had been hit by epidemics triggered by visiting fishermen and explorers. The English in Jamestown, for example, found a confederation composed of the remnants of several neighboring Native American communities. The Pilgrims at Plymouth benefited from a major epidemic as they took over an abandoned Native American townsite, complete with fields cleared for planting. As European settlements grew, they inevitably forced Native Americans off more and more of their land, while disease continued to disorganize native resistance. One estimate suggests that by the late eighteenth century, the Native American population of North America had fallen by 90 percent.

By 1770 five hundred thousand European settlers had migrated to English North America, more than half to farming colonies scattered from Pennsylvania to New England. As more immigrants arrived, more and more Native Americans were pushed aside and replaced with farmers living in communities similar to English villages. These agricultural communities soon moved beyond self-sufficiency and began to produce substantial surpluses. The colonies’ exports consisted of the same agricultural commodities produced by English agriculture. They needed to import a variety of tools, hardware, cloth, and other goods from England but could not sell their farm surpluses there. This forced the colonies to look elsewhere for markets.

Merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia responded by visiting plantations in Virginia and the Caribbean. They soon developed a profitable trade selling wheat, flour, and other goods to the tropical plantations. This allowed the Caribbean plantation owners to devote more of their land to commercial crops. The colonial American merchants took payment in silver, sugar, and molasses, which they took back home. Distilled into rum, molasses from the Caribbean gave the colonists a commodity they could profitably export to England.

The collapse of Native American populations not only set the stage for conquest of the Native American empires in Mexico and Peru but also allowed the development of plantation societies from Brazil to Virginia and the construction of an agrarian society from Pennsylvania to New England similar to that of England. The plantation colonies, dependent on labor from Africa, food from North America, and markets and capital in Europe, were at the center of what Ralph Davis once called “the great engine of trade,” a development that was integral to the economic growth of Western Europe in the eighteenth century.

Unlike the Americas, where disease favored the European invaders, in the Old World of Africa and Asia, disease hampered European initiatives. The Portuguese (1498), the Spanish (1564), and then the Dutch and the English (1590s) gradually created a complex, thinly spread European presence around the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. For the Europeans, Africa and Asia became a world not of conquest but of trade, diplomacy, and cultural adaptation. Until after 1750, the European presence in Asia was fragile. Assumptions of European hegemony in Asia before that date are projections of nineteenth-century imperialism upon an older and different experience. As the Southeast Asian historian D. R. SarDesai comments: “There was no major political or cultural European impact on the region [southeastern Asia] until well into the nineteenth century.”3

Three things worked together to define this fragile European position in Asia, limiting Europeans to a role as tolerated participants in Asian trade. The first was logistical. Sail-powered wooden ships traveling a ten-thousand-mile-long supply line rendered transport slow, expensive, and risky. The second was the vulnerability of European men to tropical climate and tropical disease. The third determinant was the fact that in Africa and Asia, Europeans were confronted by well-organized societies; the newly arrived Europeans had little choice but to learn how to participate in Asian and African trade.

Initially intent on controlling the European spice trade but hampered by an ingrained suspicion of Islam, the Portuguese superimposed their own trade network upon the existing pattern of Asian maritime trade. They created a combination of forts and trade agencies scattered from Mozambique to Timor and Macau, with their headquarters at Goa. The Portuguese used force to intervene in local disputes, but only where their modest military resources could affect the outcome. In return, Portuguese-backed local governments granted the Portuguese privileged trading rights and land for fortified trading posts.

While the Portuguese, and later the Dutch and English, networks were remarkable achievements, they only worked because their merchants and agents developed interconnections with the intricate world of indigenous merchants. Without these small-scale Arabic, Asian, and Malay traders as an interface between European agents and local farmers and craftsmen, these European companies would have had far more trouble obtaining and consolidating the output of small producers into wholesale quantities of goods.

Until 1564 the Portuguese were the only Europeans participating in Asian maritime trade. The Spaniards arrived in the Philippines from Mexico in February 1565, and by 1571 they had captured the seaport town of Manila. Before long the annual Manila galleons began arriving with large quantities of Mexican silver. Over the next half century, the Spaniards tried to build a network of trading posts in the Malukus, but they lacked the necessary resources. The merchants in Manila soon settled for a symbiotic relationship with China. Using the Southsea Chinese as intermediaries, silver arriving from Mexico was exchanged for Chinese silks and porcelains destined for the Spanish American market, while spices from the Malukus reached Manila, brought by Malay and Chinese merchants and ships. This was a tremendously profitable business for the merchants in Mexico City, and in 1594 the Crown chartered the Consulado de Mercaderes in Mexico City. The Consulado regulated the distribution of European merchandise in Mexico and adjudicated disputes between merchants. It also supervised trade with Manila, sending some of the Chinese textiles across Mexico to Vera Cruz for shipment to Seville.4

The Spanish were followed in the 1590s by the Dutch and the English. The Dutch built a trade network based on Batavia on the island of Java, while the English concentrated on the Indian subcontinent. A large part of the Dutch network was built not by capturing Asian port towns but by conquering many of Portugal’s most important Asian enclaves. The English, with an initially small budget, placed themselves under the authority of the Mughal Empire in India, successfully negotiating for a base in the Mughal seaport of Surat, the most active port in the Indian Ocean. There they began building up a profitable trade in Indian textiles. With the de facto protection of the Mughal government, they were encouraged to harass the Portuguese.

The distance to Asia made it costly to maintain large fleets so far from home. Once the great South Asian empires were consolidated in the late 1600s, the European establishments were more likely to use their limited military resources against one another. They gained control of very little additional Asian territory after the Spaniards took control of Manila in 1571.

The European presence in the Asian interior was even less imposing. Neither the Portuguese Estado da India nor the Dutch and English East India Companies ever controlled the overland routes through the Middle East. Thus the Asian commercial world easily outflanked European efforts to control Indian Ocean trade, either by using smaller ships and taking routes the Europeans overlooked or by using combinations of overland and seaborne routes protected by the seventeenth-century Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires.5

The ability of Asian states to reject European penetration was illustrated well when the Portuguese overstepped their boundaries in seventeenth-century Japan. When in 1639 the Japanese government decided the Portuguese were chronic troublemakers, the Portuguese had no choice but to pack up and leave. Similarly, when the Safavid Empire found the Portuguese base at Hormuz inconvenient, the Safavid army easily captured it. Near the end of the seventeenth century, the sultan of Oman captured the Portuguese base at Oman in the Persian Gulf. The Omanis went on to force the Portuguese out of one East African seaport after another. By 1700 the Portuguese had lost all their East African bases between Mozambique and the Persian Gulf. Even the Dutch, with the strongest European military and naval establishment in Asia, were vulnerable. China had tolerated a sizable Dutch fort on Taiwan for almost forty years (1624–1662), but when the Qing government changed its policy regarding foreign traders, the Dutch were unable to resist a determined attack by the Chinese army and navy.

Meanwhile, even as disease helped the European invaders in America, it limited European operations in the East and in Africa. In seventeenth-century Goa, for example, the soldiers’ hospital registered the death of more Portuguese soldiers than were sent from Portugal as replacements. Both the Portuguese and the Dutch lost more than a third of their men before they were “seasoned,” or acclimated enough for a serious campaign. The situation was even worse for an army in the field, where disease was augmented by poor sanitation and desertion. At least two Portuguese armies of more than five hundred men disintegrated during attempted African campaigns as the men either died or deserted. Logistical limitations, vulnerability to tropical diseases, and effective resistance placed very real limitations on European power in Asia.

All these European incursions had two things in common: (1) The people arriving from Europe were almost all single men who expected to stay abroad for several years; and (2) the silver mines of Mexico, Peru, and Japan reshaped international trade, supported the first truly global trade, and changed the European power structure.6

Marriage and the Disappearing Europeans

Whether the destination was Southeast Asia, India, West Africa, or North America, most of the migrants were men. Most of those men were unattached and expected prolonged stays abroad, and most of them married women from the societies to which they migrated. Ethnic intermarriage could be found in every colony from West Africa to India, Southeast Asia, Brazil, and the Spanish Empire. It was even common among the roving fur hunters of French Canada. In this context, the term “marriage” includes formal marriage according to the requirements of church and society as well as marriages recognized by the local society but not recognized by European legalities. The term “marriage” also includes long-term, informal liaisons between men and women that created de facto households and raised children.7 Regardless of legal or religious rules, custom, or opinion in the migrants’ home countries, newly arrived Europeans of all classes soon arranged some type of “marriage.”

In European-governed territories, the European ruling elites and their middle-class employees married according to the rules of the local church. In Portuguese or Spanish territories, it was the Catholic Church. In Dutch-controlled areas, it was the Dutch Reformed Church; and in the territories administered by the English East India Company, it was the Anglican Church. The brides, almost always Asian or Eurasian, were formally converted to Christianity and baptized before their weddings. The advantage of the formal wedding was that the legal ethnic identity of the children followed that of the European father, regardless of the mother’s ethnicity.

The soldiers, sailors, and working-class men formed liaisons with indigenous women soon after arriving, but those liaisons rarely were formalized in church. For these men the requirements, permissions, and interviews involved were insulting and pointless. The children of these informal marriages were considered illegitimate by company and church authorities, but the Dutch EIC did make one concession. If the father had his boys baptized and taught them rudimentary arithmetic and reading, they would be eligible for menial jobs in the EIC organization.

The maritime communities of southeastern Asia also had a tradition of temporary wives who helped newly arrived merchants find the contacts they needed, and Asian society had no trouble extending this tradition to Europeans. Children of these marriages usually stayed with the mother if the marriage was dissolved. As a logical counterpart to the tradition of temporary wives, divorce was a direct and simple procedure.

The contrast between the routine miscegenation of the early modern colonial world and the attitudes of the later nineteenth century is striking. The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a sharpening of racist undertones and attitudes toward intermarriage and interracial children. While the English East India Company briefly encouraged its political agents in Indian states to marry women from local ruling families to strengthen English authority,8 by the mid-nineteenth century, racial or class boundaries were well established in India. The mixed-race children of Anglo-Indian liaisons were being ostracized from white English society and excluded from English schools and the better jobs in British-controlled India.9 The process of ethnic polarization was more complex in the Dutch East Indies, where issues of class and income were more prominent, but the tension between “pure white” and Indo-Dutch grew steadily in the 1800s and became explicit after World War I.10 From general acceptance and encouragement, miscegenation became something that was not only shameful but officially illegal.11

The Puritan colonies of New England and the Quakers of Pennsylvania constituted the main exception to the general acceptance of interethnic marriage. Settled by migrants who came as families and as part of organized religious communities, these newcomers sometimes tolerated close association with Indians, as in Dutch New Netherland, but opposed marriage between European men and Native American women. Society in Spain’s American Empire lived with an intermediate compromise. The first arrivals from Spain were almost all men, and they often developed long-term relationships with Native American women, who bore their children. Once established, however, many Spaniards brought their Spanish wives and families from Spain, maintaining their Native American families in separate households.

Intermarriage was one of the reasons the European presence in Asia was more fragile than it looks. Part of that fragility derived from an underlying tension. Intermarriage facilitated commercial and political connections with the surrounding society, but the same unions made it easy for European colonists to identify with the Asian or African societies that surrounded them. Whatever her background, the wife managed the internal affairs of the household. A nominally Dutch family ate Asian food, wore Asian clothes, and left the children to be raised by Asian servants. As widows, many Asian matriarchs arranged marriages for their Eurasian children.12 By the second or third generation, the officially Dutch or Portuguese heads of households looked like Asians. By birth they were more than half Asian, and growing up they had assimilated many aspects of life in Asian society. It was not a difficult transition for these Eurasian “Europeans” to move away from European colonial capitals and join an Asian commercial society.

Thus one of the sources of fragility in the European outposts in Asia was the direct result of long-term colonization with only men. Intermarriage and assimilation were helped by a European worldview derived from medieval Catholicism (see chapter 2). This made European men adaptable, and one form of adaptation was the normalization of ethnic intermarriage. These men were much more concerned about class, family, and status; in all but a few colonial settings, race, ethnicity, and European political identity were secondary concerns. The ease with which early modern men married Asian or African women, modified their European personal identities, and assimilated to new cultures clearly separates the European expansion of 1500 to 1750 from the industrialized and often militarized imperialism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The nineteenth century saw two major developments that reshaped how Europeans defined their identity and how they regarded others. The Enlightenment laid out the proposition that all men were created equal, but, in a major contradiction, it also encouraged an approach to nature that emphasized classification and encouraged people to see differences between species and subspecies. The imposition of a racial hierarchy that separated Native Americans from Europeans is apparent in both French Canada and English America by the mid-eighteenth century. By the American Revolution, stereotypes of Native Americans had lost the aura of the “noble savage.”

The Enlightenment passion for classifying and comparing tended to emphasize the apparent differences between Europeans, Africans, and Native Americans, with white Europeans as the reference point. From there it was a short distance to racial hierarchies, especially when combined with the social Darwinism of the late nineteenth century. These ideas undermined the older habit of trying to understand other cultures by looking for similarities and instead emphasized superficial differences. In this process, ethnic or racial intermarriage implied that the nonwhite partner was not fully human and that any mestizo offspring were also inferior.13

These attitudes were further reinforced when the rise of nationalism changed the European idea of identity. Europeans were increasingly taught to identify with national communities that shared a single historical heritage and language and, if possible, identify with a state that included everyone who spoke a “national” language. By 1900 European identities of this kind became much stronger and merged with national identities that bordered on racism. In that context, interracial marriage meant consorting with someone who was racially inferior.14

Silver and Early Modern Trade

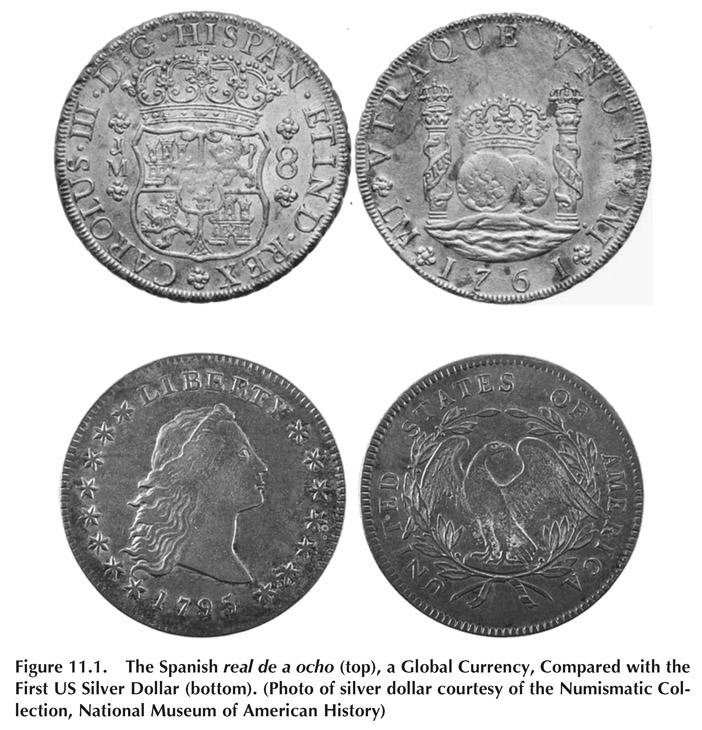

From this distance, it is hard to grasp the importance of the silver mines the Spaniards found in Mexico and Peru. By one estimate, Spain’s American Empire sent enough silver to Europe to increase its silver supply by 600 percent. This American silver gave Europe a commodity that China and other Eastern countries would accept in return for their Asian commodities and manufactures. It was not Europe that made Asian trade dynamic; the dynamism came from the interaction between immense new supplies of American silver and the size and wealth of the Chinese and Mughal Empires.

The intensity of the international demand for silver grew out of the fact that China and India had both developed silver-based monetary systems during the 1500s. Neither empire had large domestic sources of silver, and both economies were growing faster than their domestic silver supplies. As silver became scarcer, it became more valuable, and a single ounce of silver bought increasing amounts of other commodities. Since either of these two economies was larger than the economy of Europe, the international markets attracted silver to Asia from silver-producing regions all over the world, especially Mexico, Peru, and Japan.

Both the Mexican and Peruvian silver mines were in Spain’s American Empire, but they were developed by European investors and ruled by Spain. They reached full-scale production around 1560 and roughly three-quarters of their output was shipped to Spain. A quarter of the American silver output belonged to the king of Castile as royalties and tax revenue; the rest belonged to the investors and merchants who had developed the mines and sold merchandise to the growing American market. Within Europe the new supply of silver made it easier to borrow money for new investments in manufactures, plantations, and trade. European trade with Asia, which had been hampered by the lack of salable European exports, began to expand. The Portuguese trade around Africa was supplemented by the Italian, French, and English merchants who rebuilt the overland trade through the Middle East.

Eventually, 30 to 40 percent of the American silver sent to Europe flowed through the Middle East to Asia, where it was used to buy Asian goods. Dutch merchants and members of the Hanseatic League took silver to Poland, Lithuania, and Moscow to buy grain, iron, and shipbuilding materials. From there it traveled to the Caspian Sea and Persia. Similar trade brought silver to Austria, the Balkans, and the Ottoman Empire. The Spanish government used the silver to pay its debts to Italian bankers, and eventually that silver turned up in the hands of French and Italian merchants in the Ottoman Empire, where they bought Syrian and Iranian silks and Asian spices from farther east. In the Middle East, the silver from Europe was used to buy silk in the Safavid Empire; from there it was used to pay for cotton textiles and luxury items from the Mughal Empire. Once in India, some of the silver became part of the money supply, but some bought spices from the East Indies and silks from China. Thus American silver expanded Europe’s ability to buy Asian goods before it moved through the economies of southern Asia.15

The merchants in Mexico City were well aware that, despite many middlemen, the silver they sent to Europe was worth 50 percent more than its European value once it reached China. They estimated that if the same silver could be shipped directly from America to China, avoiding many middlemen and transactions costs, it could be sold in China for 100 percent profit. When direct trade from Mexico to Manila began in 1571, it proved that it was indeed very profitable to send American silver direct to Asia.

American silver affected world trade in several ways. It increased Europe’s ability to buy Asian goods. It facilitated the expansion of trade and manufacturing across East Asia and China. Silver also changed Spain’s American Empire, moving it from the European periphery to a central place in world trade. As the economy of Spain’s American Empire matured, it retained more and more of the silver it produced, using it for investments in the Spanish American economy, for the Manila galleon trade, and for its growing contraband trade with northern Europe. This had a devastating effect on the Habsburg Empire in Europe, which depended on remittances from America to finance its wars. During the second quarter of the seventeenth century, the decline in the Spanish Crown’s silver receipts undermined the finances of the Habsburg Empire in Europe, and by 1660 France had replaced Spain as the dominant power in Europe.

European trade in the East, however important it was to Europe, had only a marginal impact on the social and political history of Asia. At times Portuguese, Dutch, or English sea power was a factor that Asian states had to reckon with, but European military resources were used more often against other Europeans than against Asians.

The masculine nature of the migration we call European expansion, the widespread acceptance of racial intermarriage, and the normalization of miscegenation in Europe’s main Asian outposts represent a European behavior very different from the imperialism of the nineteenth century. Nineteenth-century imperialism brought women as well as men to its colonies. Colonial society imposed increasingly rigid class and racial boundaries upon colonial society and rejected intermarriage. Households minimized contact between white Europeans and Asian servants. The children of interracial marriages, once an asset in a diverse commercial world, were rejected by their European relatives and assimilated into the families of their Asian relatives. The part-European Creole elites of the old colonial capitals were subordinated to a new, all white governing elite.

In a longer historical perspective, the limits of nineteenth-century Western domination are apparent. As early as 1896 a modernizing Ethiopia destroyed a modern Italian army at Adowa. It took more than two hundred thousand troops and twenty thousand British fatalities to defeat thirty thousand militia and guerillas during the Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902). In the 1890s Japan began its climb as a major power by purchasing state-of-the-art industrial machinery and battleships from Europe. By 1910 Japan had developed its own radio communications technology and was building the fastest and most powerful warships in the world. By the 1920s the English had endowed India with an industrial infrastructure that included textile mills, railroads, and steel mills. They were managed by Englishmen but operated by Indians. The educated Indians who staffed the emerging civil service and second-tier positions in industry energized the Indian independence movement of the 1930s. Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign of passive resistance was close to victory when postponed by World War II. The Suez Canal Crisis of 1956, when Israeli, French, and British troops invaded Egypt, did not stop Egyptian nationalization of the canal, nor did five hundred thousand American troops and fifty-eight thousand American fatalities stop North Vietnam from taking control of all Vietnam. Both great world powers—the Soviet Union and then the United States—encountered a formidable foe in the guerillas of Afghanistan. The disintegration of political stability in the Middle East since the second Iraq war and the presence of nuclear weapons in places like North Korea and Pakistan all suggest the limits of Western authority.

With Western hegemony on the wane after only two centuries, the current reality resembles that of the seventeenth century, when the world was dominated by several centers of power. Currently about 40 percent of our imports come from East Asia, including products of heavy and high-tech industries that once defined Western primacy. China’s gross domestic product (GDP), calculated as Purchasing Power Parity, is larger than that of the United States. The United States is now second, followed by India (3) and Japan (4). Moreover, every country from Korea to India is growing two or three times faster than the United States and Europe (see note).16 Asian companies sell more cars in the United States than Ford and GM together. Brazil, a rising industrial power, builds commercial airliners; Volvo is a subsidiary of a Chinese automaker; and Jaguar is a subsidiary of India’s Tata Industries. The Chinese car market is bigger than that of the United States, and its economically comfortable middle class is larger than the entire population of the United States.

The world increasingly looks like a high-technology version of the seventeenth century. The counterparts to silver as a high-value commodity are now oil and foodstuffs. As the climate continues its shift, more and more areas will be vulnerable to rising oceans, while drought-induced shortages will make freshwater as valuable as oil. A careful look at the realities of European influence in Asia during the seventeenth century might suggest ways to manage the problems and advantages of the multipolar world we see taking shape around us.