We have seen kinship myth used for the benefit of the state as well as for the glory of the individual. As king of Macedon (336–323 BCE) Alexander the Great was the state, but his successes proclaimed his personal glory as well. Indeed, the glory that Alexander achieved burns so brightly that the real man is often hard to find in the surviving sources. The problem is that those sources are centuries removed from the real Alexander. They rely on accounts often written in his own lifetime, but even those accounts provided varying interpretations of the king, his personality, and his achievements. This was partly because of the complex picture Alexander himself conveyed, a complexity that arose from his own erratic personality, the different images he put forth toward different parties (Greeks, Macedonians, Persians, among others), and the changes he underwent in the course of his conquest of Asia.

Avenging the Persian atrocities in Greece 150 years before provides the initial context for his invasion of the Persian Empire in 334. So does Homer, for as the great avenger of hellenic civilization, Alexander would become a latter-day Achilles and take his stand as the most successful and honorable warrior ever, imbued with the competitive spirit of the Homeric world. With the text of Homer under his pillow at night, so the story goes, given to him perhaps by his teacher Aristotle, and wearing armor from the days of the Trojan War, which he took from Troy itself, Alexander sought to outdo the achievements of all before him, including, and especially, his father Philip II. It was, in fact, Philip who was largely responsible for instilling such a mindset. The archaic Macedonian society over which Philip presided required his heir to be a worthy successor. Fredricksmeyer sums it up well,

The ideological context of this relationship was a value complex that had been preserved in Macedonia, along with some of its institutions and customs, from Homeric times, and may be described, in a word, as the cult of the heroic personality. It placed the highest premium on success, power and glory, and regarded as the highest virtue, to be sought with the utmost exertion, the prowess and superior achievement (arete) of the individual hero, both for its own sake, and for the sake of honor (time) and glory (kydos) among his fellow men. As in Homer, the noblest competitor was the warrior king, and the most appropriate arena of competition was the field of battle, war and conquest.1

Where Alexander differed from Philip is the lengths to which the former went to achieve immortality and perhaps literal godhood as well. For as the campaign progressed, as the Persian Empire succumbed piece by piece, and then as the edge of the world beyond Persian realms beckoned, Alexander seemed transformed, aiming for goals of conquest and divinity that he did not begin with in 334. And yet in the midst of this transformation there is a fundamental pragmatism that prevailed in the way Alexander administered his empire. Most pressing was the need to have the Greek, Macedonian, Persian, and other elements work together in the new empire. Rather than dreaming of a “unity of mankind,” Alexander’s methods of mixing races in new city foundations, incorporating different elements in his armies, and other measures suggest a practical approach to imperial rule. For example, it has been noted that while he retained many of the Persian satraps for their knowledge of local administrative operations, the finances and the military remained firmly in Macedonian hands.2

In his use of kinship myth, we see these two contrasting sides of Alexander come together. The evidence shows that Alexander embraced the reality of the Greek heroes and their feats; at the same time, it suggests a certain logic in his use of kinship myth. The pragmatism Worthington and others have identified in Alexander’s administration applies also here. Kinship myth was a political and diplomatic tool, often a useful alternative to military methods. Even as he likened his own victories to the successes of Heracles, even as his decisions to visit Troy and Siwah and to besiege Tyre and Aornus were influenced by his desire (his pothos, as Arrian called it)3 to emulate and surpass his heroic ancestors, he also used these ancestors to secure the allegiance of a city by claiming to be related to its people (or at least its leaders). Sometimes the city’s leaders, to save themselves as Alexander’s army approached, took the initiative and made the claim, which Alexander readily acknowledged. Such a link was intended to justify Alexander’s overlordship and strengthen the bond between conqueror and conquered.

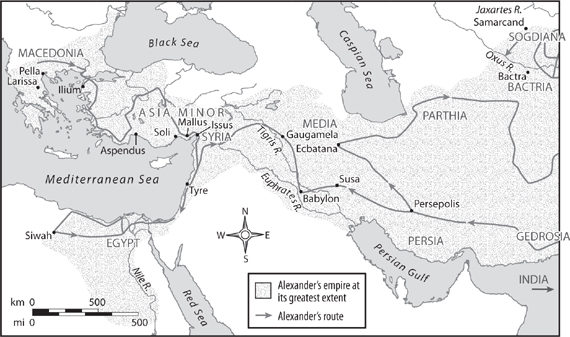

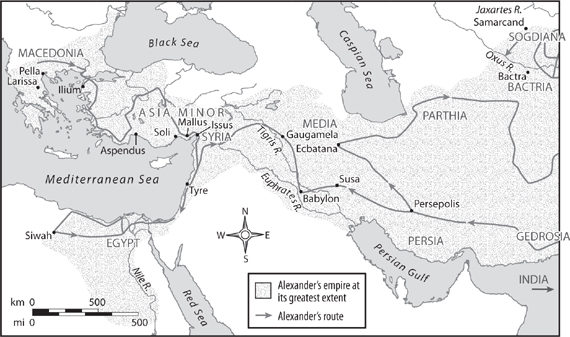

MAP 5.1

Empire of Alexander the Great

Alexander usually turned to Heracles and Achilles for a link of kinship, although at Ilium, which he believed to be Homer’s Troy, he asserted a link through Andromache. Further on in the campaign he may also have invoked the god Dionysus, but, as we shall see, the questions of whether the tradition of Dionysus’ ancestry predated Alexander and whether Alexander actually used Dionysus in kinship diplomacy are very problematic. But we can certainly say that the traditions involving Heracles and Achilles developed long before Alexander was born. The invention and development of these traditions arose in response to the Macedonians’ need to assert their hellenic identity, which was largely questioned and often rejected by the Greeks further south. Alexander himself was descended from Achilles on his mother’s side, for Olympias was of the ruling Molossian house of Epirus, named for Molossus, son of Neoptolemus and grandson (or great-grandson) of Achilles. Alexander’s paternal line was the royal family of Macedonia, called the Argeadae, who traced their descent back to Heracles through the Temenids of Argos. The similarity of Argeadae and Argos of course bolstered the claim.4

Like his predecessors, Alexander the Great was a Macedonian king first and aspiring Greek second. But, as we have noted, his world was clearly imbued with myth, and while he sought to profit from myth in the conventional ways, he outdid the previous kings by associating himself with the heroes as none before, surpassing even Philip. In his use of kinship myth specifically, a pattern emerges that suggests the pragmatism we have noted in other aspects of his conquests and administration. Most of the examples of Alexander’s use of kinship myth occur early on in his campaign. Alexander took advantage of his link with the Aleuadae of Larissa, with Ilium, and with Mallus and Aspendus in Cilicia. There is also evidence that suggests he may have recognized a link to the Nysaeans, the Sibi, and the Oxydracae in India. At Larissa, Ilium, and Mallus, Alexander made the initial claim, while the locals from Aspendus approached him to save their city, as did the Indian tribes, if those accounts can be trusted.

There seems to have been in each of these cases some tradition to support the claim, though the evidence of it in India is more tenuous. That all the other cases come from Asia Minor and Greece is highly significant, for this shows that in those regions, Alexander tended to employ a well-established tradition, whereas in regions to the East, he and his men were accused of considerable mythological fabrication.5 Where displaying his aret , or heroic virtue, was concerned, Alexander did not mind a little flattery. For the practical business of securing his conquests, however, he tended to employ myth as a political tool only if efficacious. As we shall see, the exercise of kinship myth in India is another matter altogether. If genuine, it is the only place in the nonhellenic realms beyond Asia Minor where Alexander employed kinship myth, and by the time he reached those areas, the matter had become complicated by his likely aspirations of divinity. As for the Greeks, although they generally hated him and secretly hoped his campaign in Asia would fail, I will argue below that at least some of the success he had with kinship diplomacy was the result of a sincere belief among the Greeks of his hellenic descent, even as they regarded him as alien by virtue of the culture in which he was raised and especially by virtue of his policies.

, or heroic virtue, was concerned, Alexander did not mind a little flattery. For the practical business of securing his conquests, however, he tended to employ myth as a political tool only if efficacious. As we shall see, the exercise of kinship myth in India is another matter altogether. If genuine, it is the only place in the nonhellenic realms beyond Asia Minor where Alexander employed kinship myth, and by the time he reached those areas, the matter had become complicated by his likely aspirations of divinity. As for the Greeks, although they generally hated him and secretly hoped his campaign in Asia would fail, I will argue below that at least some of the success he had with kinship diplomacy was the result of a sincere belief among the Greeks of his hellenic descent, even as they regarded him as alien by virtue of the culture in which he was raised and especially by virtue of his policies.

Alexander’s link with the Aleuadae of Thessaly is the best documented and supported in the ancient texts. The incident in which he affirmed the link occurred very soon after Alexander’s accession in 336, following the assassination of Philip. Resistance by the Thessalians was part of a greater problem of general upheaval in the Greek world after Alexander took the throne. After Philip had established a Macedonian hegemony, the Greeks were hopeful that the transition to the new king would give them the chance to throw off the Macedonian yoke once and for all. But Alexander was too quick for them, meeting all opposition with his characteristic fervor. Bringing Thessaly back into the fold was especially important, for Alexander had need of its cavalry in the upcoming invasion of Asia.6 After outmaneuvering the Thessalians on the field,7 Alexander proceeded to Larissa and convinced the ruling Aleuadae to support him. He claimed in part to have inherited the title archon from his father, by which he claimed leadership of the Thessalian League. Moreover, like Philip, Alexander had a claim of kinship; indeed Alexander had an extra link not available to his father. As Diodorus explains, Alexander solidified his hold by “reminding the Thessalians of their ancient kinship through Heracles and encouraging them with kind words and great promises.”8 Justin gives this account: “During his passage he encouraged the Thessalians and reminded them of the kindnesses of his father Philip and of his relationship with them through his mother, who was of the race of the Aeacids.”9

FIGURE 5.1

The Heraclean Link of the Argeads and Aleuads

We have seen how well documented the Argead kings’ descent from Heracles was.10 But how did Heracles connect Alexander with the Aleuadae? Alexander and the Thessalians were likely thinking of a son of Heracles named Thessalus (Figure 5.1). Beyond Thessalus, two further avenues present themselves, his sons Pheidippus and Antiphus or a son named Aleuas the Red, eponym of the Aleuadae. The personages of Thessalus, Pheidippus, and Antiphus go all the way back to Homer, whom Strabo cites in his assessments of early Dorian migrations. The brothers are listed in the Catalogue of Ships as leading a contingent from Cos and other islands of the Dodecanese.11 Strabo elsewhere records several different traditions about the origins of the Thessalians and mentions two separate figures named Thessalus from whom the name Thessaly derived. One of them was son of Haemon, the other son of Heracles. Strabo adds that in the latter case, Thessaly was named by the descendants of Pheidippus and Antiphus, who came from Ephyre in Thesprotia, a region of Epirus.12

After the Trojan War, in which Antiphus had participated, he himself occupied “the land of the Pelasgians” and called it Thessaly,13 a variation on the idea that it was his descendants who did the deed.14 The divergence widens, for here we have no sense that Antiphus came by way of Epirus, only that he started out in Cos and ended up in Thessaly. These variations likely reflect the post-Homeric traditions that developed at the hands of the early mythographers, in particular Hecataeus of Miletus, who was Strabo’s main source for matters concerning Epirus and Macedon,15 and Pherecydes of Athens, who provides details that are recapitulated in Apollodorus.16 As we shall see, a similar situation arises in Alexander’s maternal line, in which Homer has Neoptolemus return to Thessaly directly from Troy. The most likely explanation is that the post-Homeric versions developed in response to the need of early archaic families and communities to situate themselves in the mosaic of heroic “history” and occasionally diverted returning heroes accordingly. Aleuas likewise may have performed a similar function, his name serving to connect the Aleuadae to heroic times and to a heroic figure. Aleuas, grandson of Heracles, was purportedly the first tagos, or chief of Thessaly, and according to Aristotle, he divided Thessaly into tetrarchies and organized the army according to kleroi, or lots.17 With Aristotle as our source and the use of an eponym predating Alexander (even though most of the attestations are much later), Aleuas strikes me as the most likely avenue Alexander would have used to connect Macedon’s royal house with the Aleuadae.

Meanwhile, on the maternal side, Justin mentions the Aeacids (11.3.1).18 He is, of course, referring to the descendants of Aeacus, the grandfather of Achilles. Alexander’s mother Olympias was from Epirus, in northwestern Greece, whose ruling family was the Molossi. This dynasty traced its origins to Achilles’ son Neoptolemus, who left Troy with Andromache and came to Epirus, bypassing his father’s home of Phthia in Thessaly (Figure 5.2). Neoptolemus then subdued the natives in Epirus and established a dynasty. The natives are called Molossians already in the sources, but the implication is that the son of Neoptolemus and Andromache, Molossus, gave his name to the people.19 Afterwards, Neoptolemus seems to have returned to Thessaly to become the forefather of the kings in Phthia, from whom the Aleuadae claimed descent.20 In Strabo’s version, it is to Pyrrhus, son of Neoptolemus, and to Pyrrhus’ descendants, “who were Thessalians,” that the Molossians became subject.21

FIGURE 5.2

The Epirote-Thessalian Connection

The names Pyrrhus and Neoptolemus are often interchangeable, but Strabo’s remark may explain the divergence from the Homeric version, which has Neoptolemus return to Thessaly directly from Troy. That version would be consistent with Strabo’s if we assume that Neoptolemus’ son, not Achilles’, went to Epirus. The Pyrrhus variant perhaps comes from Hecataeus, but the origin of the Neoptolemus version is likely the Nostoi by Agias of Troezen, from the seventh century, as we know from Proclus’ summary. The lost epics and the mythographers of the seventh and sixth centuries did much to develop the old myths with an eye toward filling out, for example, the Trojan War cycle, and to sort out chronological and other inconsistencies, as I noted before. The archaic innovations that find more copious citation in later sources, however, probably served political aetiological purposes as well. Certainly in the fourth century we should expect Neoptolemus or his son to be the link between Alexander’s maternal line and the Aleuadae.

There is no way to know, of course, if we should choose between Diodorus or Justin, or if Alexander had invoked both connections. It would not be surprising to see him take full advantage of the mythological opportunities afforded to him. In any case, Alexander had an ancient tradition to back him up on both counts, and the sources suggest that the Thessalians were convinced of his claims. While it is true that the threat of overwhelming force would be enough for them to agree to any declarations of kinship, it is noteworthy that Alexander should bother to put forth a mythological justification to bolster his unassailable logistical position. The Thessalians, like most Greeks, may have had little love for their northern neighbor, but Alexander saw kinship myth as a way of making his leadership more palatable, and we have no reason to reject Thessalian credulity on this point. Already in Thessaly we see in the mythopoeic mind of Alexander that heroic ancestors served Macedonian imperialism as much as they enhanced Alexander’s ego.

Ego was no doubt in play when Alexander laid a wreath on the tomb of Achilles at Ilium, while his closest companion Hephaestion laid one on the tomb of Patroclus,22 suggesting to Aelian that Alexander’s relationship with Hephaestion was similar to that of Achilles with Patroclus. However, of greater symbolic value to the consolidation of his empire was Alexander’s acknowledgement of kinship with the Trojans through Andromache. Strabo says that he “provided for them on the basis of a renewal of kinship and because of his zeal for Homer…. On account of this zeal and of his kinship through the Aeacids, who had been kings of the Molossi, of whom Andromache, Hector’s wife, as the story goes, was also queen, Alexander treated the Ilians kindly.”23 The benefactions that Strabo describes may have included remission of tribute, as Alexander would grant to the people of Mallus. More importantly, as Bosworth has pointed out, Alexander abandoned Herodotus’ view of the Trojans as eastern barbarians. Rather, they were “Hellenes on Asian soil…. The descendants of Achilles and Priam would now fight together against the common enemy. It was a most evocative variation on the theme of Panhellenism, and Alexander proceeded to battle with the ghosts of the past enlisted in his service.”24

Alexander swept through Asia Minor in 334 and 333, eventually reaching Aspendus in Pamphylia. Knowing which way the wind was blowing, the Aspendians saved Alexander the trouble of an attack and surrendered to him outright, requesting that they be spared a garrison. Strabo indicates that Aspendus had been founded by the Argives. He is supported by an inscription found at the Sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea, which reveals that the Argives, probably in the last third of the fourth century BCE, acknowledged a tie of kinship with the Aspendians and that the former were granting them citizen rights.25 And so Alexander agreed to the Aspendians’ request, although he still extracted fifty talents and the contribution of their horses. The Aspendians were wealthy and could afford such a contribution.26

The Aspendian episode ultimately demonstrated that, even when the opportunity presented itself, Alexander would not embrace his brothers when they tried to undermine his authority. They subsequently had a change of heart and refused to pay the fifty talents. Alexander exacted a second surrender from them after they saw his vast army, and his new demands were far harsher: one hundred talents, the horses, hostages, the implementation of a satrap, yearly tribute, and a reassessment of their territory.27 Though a kindred people, their defiance was intolerable, for it undermined the goal that kinship myth helped achieve and, perhaps more ominously, was seen as a challenge to the will of Alexander.

Thebes had already learned this harsh lesson. During the aforementioned upheavals following Alexander’s ascension, the young king, who had gone out of his way to employ kinship diplomacy with the Thessalians, whose cavalry he needed, decided to make Thebes be an object lesson. Alexander spent the early years of his reign reestablishing the ties his father had made, claiming the command of the Thessalians and other positions. Alexander also reconstituted the League of Corinth, an alliance of Greek states intended to maintain the so-called Common Peace. The Macedonian king was hegemon, or military leader, because, after all, Macedon was the strongest state and in the best position to insure the peace. But technically, the authority for action was vested in the League.

While Alexander was securing his northwestern frontier in 335, a rumor spread that he had been killed, and so Thebes decided to try to throw off the Macedonian yoke. In a lightning march southward, Alexander caught Thebes off guard and sacked the city. Its final fate rested with the League of Corinth because Thebes was a member and had violated the Common Peace. The decision was to raze the city to the ground.28

In the course of these discussions, according to a tradition that possibly begins with Cleitarchus, a Theban prisoner named Cleadas was allowed to speak. His case for leniency from Alexander included the use of kinship myth, for Thebes was the traditional birthplace of Heracles. Alexander was unmoved by Cleadas’ pleas and allowed the destruction of Thebes, except for the house of Pindar.29 There is a variant of sorts in the Greek Alexander Romance, a work whose origin is extremely difficult to trace but may lie as early as the third century BCE. Not a historical work per se but more of an ancient novel of Alexander’s adventures, filled with fantastical and absurd situations, the Romance preserves material that had begun to circulate soon after Alexander’s death.30 Here, we find a Theban musician named Ismenias throwing himself at Alexander’s feet amidst the carnage as Thebes is sacked. He reminds Alexander that Thebes was the birthplace of Heracles and Dionysus and asks for mercy on the basis of kinship. But, again, Alexander is unmoved, chastises Ismenias, and razes the city.31 There is no bona fide historical evidence that the Thebans attempted to assuage Alexander’s anger by way of kinship myth when he destroyed their city in 335, but even if the posthumous accounts are groundless on this point, they preserve an important idea about Alexander, which the Aspendus episode also demonstrates, that ties of sungeneia accounted for nothing if the sungenes posed any threat to Alexander and his plans.

The examples of Soli and Mallus, further to the east in Cilicia, also bring home the pragmatism in Alexander’s use of myth. Both cities were of Argive origin.32 The same inscription that refers to Aspendus also indicates that the people of Soli were granted access to the Argive assembly.33 Meanwhile, according to legend, Mallus had been founded by the Argive Amphilochus son of Alcmaeon, one of the Epigoni against Thebes.34 On the one hand, Alexander punished Soli for its pro-Persian leanings with a fine of two hundred talents of silver and by imposing a Macedonian garrison.35 On the other hand, Alexander “spared the Mallians the tribute they used to pay king Darius because the Mallians were descendants of the Argives, and he himself claimed to be descended from the Argives through the Heracleidae.”36 Such remission of tribute was exceptional.

The difference in treatment is instructive. Both cities were of Argive origin but not specifically Heraclid. Alexander cited his connection to Mallus, but the ancient sources say nothing of such a claim regarding Soli. Bosworth suggests that Mallus, which lay at the eastern end of the Cilician plain (while Soli lay at the western), had the potential to aid the Persians in Alexander’s rear as he advanced toward Issus.37 Thus, its loyalty was far more paramount than Soli’s, which was more isolated. It would seem then that Alexander ignored his Argive link to Soli because there was no practical advantage in citing it. At Soli, he showed once again that kinship myth need not hinder him from asserting his will or extracting needed funds for the campaign, while the Mallus episode reinforces the argument that kinship myth was a tool at Alexander’s disposal when he made decisions of strategic importance.

We do not hear of another instance of kinship diplomacy of this sort until Alexander reaches India. There, he supposedly acknowledged sungeneia (this time, not consanguinity but a close affinity nonetheless) with the Nysaeans, the Sibi, and possibly the Oxydracae. These cases present considerable problems, the most fundamental of which is that well-established traditions are not in play but rather questionable scenarios with tenuous foundations. There was (and continues to be) much discussion of the role of Macedonian fabrications that glorified Alexander’s accomplishments in India.

In light of this discussion, it would be instructive to consider first how Alexander behaved in other parts of Asia, where there was the potential for kinship diplomacy, especially with the people of Tyre, the Egyptians, and the Persians. The evidence suggests that Alexander did not attempt kinship diplomacy with any of them. The case of Persia is particularly surprising, given the well developed and long entrenched tradition of Persian-Argive kinship. We must then ask not only why Alexander did not seize the opportunity in these places but what accounts for the claims that he did when he encountered the Indian tribes.

Alexander’s campaign received an enormous boost when he defeated Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333, not far from the southeastern fringe of Asia Minor. From there Alexander went down the Phoenician coast. His next objective was Tyre, an island city about half a mile off the coast, whose capture was essential lest it continue to serve as a naval base for the Persians, threatening Alexander’s planned excursion to Egypt, not to mention the Greek world he had left behind. The Phoenicians were not Greeks, but they interacted heavily with them. They worshiped a god named Melcart, which most Greeks equated with the deified Heracles.38 So naturally Tyre drew Alexander’s attention for both strategic and sentimental reasons. Although Alexander claimed he wanted to worship Heracles in their city,39 the Tyrians had no interest in allowing the Macedonian king within their walls, especially as it was the period of the great annual festival for Melcart, and they did not wish to give Alexander any opportunity for posing as their ruler, for whom the rights of making a sacrifice to Melcart at this time were preserved.40 Alexander’s reaction was violent, and he set about besieging the city from January to August of 332.

His response to Tyrian defiance is not surprising, given what we have already seen about Alexander’s attitudes on these matters. Clearly his pride had been hurt, and he required retribution.41 It is interesting to note that while Alexander’s descent from Heracles obviously informs his desire to sacrifice in Tyre, there is nothing in the sources about claims of kinship with the Tyrians. The closest we come is a notation in Curtius, who says simply that the Macedonian kings regarded themselves as descendants of Heracles.42 This belief was explicitly used as a justification for conquest elsewhere, but such a justification is muted here. Nor did Alexander try to reconcile the Tyrians after his victory, when, having captured the city, he went ahead with his sacrifice.43 Though they were a non-Greek people, he must have expected the Tyrians to believe Melcart was the same as Heracles, or else he would not have insisted on his own Argead connections to the hero/god. That expectation was not unjustified because the Phoenicians and their colonists (notably Carthaginians) had spent centuries interacting with Greeks across the Mediterranean, in both trade and war. But their defiance removed any possibility for kinship diplomacy and may account for the silence on sungeneia in our sources.

Before turning eastward to deal with Darius himself, Alexander went to Egypt to replace Persian control there with Macedonian. His detour to the western oasis of Siwah, where the oracle of Ammon lay, speaks to a more personal motive in Alexander’s Egyptian diversion. This Ammon was believed to be the equivalent of Zeus. As conqueror of Egypt, Alexander was to become the new pharaoh and thus, by default, son of Ammon. As for his hellenic identity, Alexander’s status of royal descendant of Greek heroes was about to get an upgrade, as the oracle would confirm that Alexander was a son of Zeus. This episode forms the centerpiece of most discussions of Alexander’s Egyptian excursion and is extremely murky, given the uncertainties of what actually happened when he consulted the oracle alone.44

Although the Greeks applied their syncretic tendencies to Egypt,45 there is no evidence that Alexander employed kinship myth here. There are indications of heroic emulation in his visit: as Arrian says, “Alexander had a desire to rival Perseus and Heracles,”46 but nowhere is it apparent that Alexander applied his perceived descent from Ammon to his relations with the Egyptians. The Egyptian point of view in our sources is mainly limited to an acknowledgment of Alexander as their new leader,47 but again we have nothing about any other connection to Alexander. That suggests that, Greek belief notwithstanding, there was no tradition in Egypt with which Alexander could work to support his legitimacy. While he need not have anyway because the Egyptians readily acknowledged him to be the pharaoh, we have seen Alexander elsewhere take that extra step.

We should certainly expect Alexander to have taken advantage of the tradition ingrained in the Greek world that connected the Persians with Argos. However, Alexander apparently did not seek to unite his empire by stressing the kinship of Macedonians and Persians through Perseus, who was an ancestor of Heracles, despite the authority of Aeschylus, Herodotus, and Hellanicus, and no doubt others, on which the attempt could have rested.48 The reason quite simply is that the Persians themselves had no such beliefs. We saw in Chapter Three that the stories in Herodotus and others are typical Greek attempts to bring order to a hellenocentric world, organizing the various “barbarian” peoples in relation to personages from Greek mythology. Alexander understood this. If it had been available to him, Alexander would undoubtedly have found kinship myth very useful.

He clearly was concerned to legitimize his rule of the Persians and sought connections where he could. For instance, Alexander married Darius’ daughter Stateira and Artaxerxes III’s daughter Parysatis.49 His stance as leader has been discussed at length, with general agreement that Alexander positioned himself not as the Great King of Persia but rather as “King of Asia,” incorporating Macedonia into an empire grander than the one ruled by the Achaemenids. This partly answers the question of how he could claim to be avenging the Greeks for Persian outrages and then assume the leadership of the hated Persian Empire.50 Debate over his attitude toward the Persians has been vigorous, but Alexander clearly meant to promote a connection with them. This intention helps to explain his adoption of Persian royal attire (though in combination with Macedonian) and certain customs, including the disagreeable proskyn sis, the ritual abasement that was normal for subjects of the Persian King but anathema to Greeks. He also pursued a policy of mixing Persians, Greeks, and others in cities across the empire; a mass wedding of Greek men and Asian women in Susa; and the incorporation of Persians into the army. There were pragmatic reasons for all this, having to do with maximizing his legitimacy and political control in the empire and promoting greater efficiency. His retention of Persians in his administration reveals that while Persian satraps often provided a smoother continuity from the old regime, the main bases for power, finances and military, remained firmly in Macedonian hands.51

sis, the ritual abasement that was normal for subjects of the Persian King but anathema to Greeks. He also pursued a policy of mixing Persians, Greeks, and others in cities across the empire; a mass wedding of Greek men and Asian women in Susa; and the incorporation of Persians into the army. There were pragmatic reasons for all this, having to do with maximizing his legitimacy and political control in the empire and promoting greater efficiency. His retention of Persians in his administration reveals that while Persian satraps often provided a smoother continuity from the old regime, the main bases for power, finances and military, remained firmly in Macedonian hands.51

Yet, Alexander still fell short of connecting with his Persian subjects as much as he might have. He did not worship Persian gods or truly understand Persian customs. His coronation was not held at Pasargadae, which would have meant invoking Ahura Mazda, the main Persian god with whom the Achaemenid kings were ritually and politically associated.52 The burning of the palace complex at Persepolis is key to understanding Alexander’s relations with the Persians and yet remains one of the more vexed issues. Some of our ancient sources suggest that the fire was the result of drunken debauchery and essentially accidental. According to Arrian, however, Alexander saw it as an act of retribution, a significant symbol for the Greeks.53 Most scholars tend to see the destruction as deliberate and argue about Alexander’s motivation. At the very least, we can say that its deliberate destruction would have undermined Alexander’s legitimacy in the eyes of the Persians. Little did he know that in the months that would follow Darius would be dead, a usurper named Bessus would present a new threat, and Alexander’s need to assert his legitimacy would be greater than ever.54

Overall, Alexander’s understanding of Persian culture, including the relationship among religion, king, and nobility, was quite limited. Given this deficiency, invoking Greek myth should have bolstered his claims of legitimacy; he clearly was shrewd enough to recognize that however ingrained the traditions of Persia’s Argive origins in Greek tradition, which likely informed his own belief in such sungeneia, there was no promise of these traditions being of any use to him. The Persians themselves simply did not share them. He tried other methods, including political marriage, to assert a link with Darius’ family, but Alexander recognized, even after the sack of Persepolis when his need for legitimacy was greatest, that kinship diplomacy was not an option open to him.

So far the pattern suggests that Alexander used kinship myth only when he felt it was grounded in some mutually recognized reality (as well as in situations in which the conquered did not defy him). He had that recognition in cities inhabited by Greeks, but the deeper he moved into the non-Greek world following his victory at Issus, the fewer the possibilities. This brings us at last to Alexander’s invasion of India and the most enigmatic example of kinship diplomacy. As has been mentioned, Alexander supposedly acknowledged sungeneia with the Nysaeans and the Sibi and possibly with the Oxydracae. As usual matters are not helped by the fact that our main sources are removed from these events by uncomfortable degrees.

First, the Nysaeans: in 326, Alexander was moving through modern Nuristan in northeast Afghanistan, conducting essentially a campaign of terror in the Indus Valley. Before he reached Nysa, or possibly as he was preparing to attack it,55 a delegation of Nysaeans led by Acuphis approached Alexander’s camp. They were led into his tent and were startled to find him in full armor (as if preparing to attack). Acuphis then petitioned Alexander to leave their city independent, “out of reverence for Dionysus” ( ), who they said had founded the city, naming it after his nurse Nyse. The Nysaeans themselves were descended from followers of Dionysus, soldiers and Bacchi, with whom the god had peopled his new city.56 Of Alexander’s reaction Arrian says, “Alexander was delighted to hear all these things, and he willed it that the accounts of the wandering of Dionysus be credible. He wanted Nysa to be a colony of Dionysus so as to have reached the point himself whither Dionysus had reached, beyond which he would pass afterwards.”57 And so Alexander granted the Nysaeans’ wish and levied three hundred horsemen from their ranks. Afterwards, he went to Mount Merus and saw the ivy that proved Dionysus’ transit through the region, as the Nysaeans had claimed. Some of the officers then made wreaths of ivy and, adorned with them, danced and frolicked, as if possessed by the Bacchic spirit (so the story went).58

), who they said had founded the city, naming it after his nurse Nyse. The Nysaeans themselves were descended from followers of Dionysus, soldiers and Bacchi, with whom the god had peopled his new city.56 Of Alexander’s reaction Arrian says, “Alexander was delighted to hear all these things, and he willed it that the accounts of the wandering of Dionysus be credible. He wanted Nysa to be a colony of Dionysus so as to have reached the point himself whither Dionysus had reached, beyond which he would pass afterwards.”57 And so Alexander granted the Nysaeans’ wish and levied three hundred horsemen from their ranks. Afterwards, he went to Mount Merus and saw the ivy that proved Dionysus’ transit through the region, as the Nysaeans had claimed. Some of the officers then made wreaths of ivy and, adorned with them, danced and frolicked, as if possessed by the Bacchic spirit (so the story went).58

There are essentially two layers to this account: the indisputably historical and the highly suspect. That Alexander visited and peacefully subdued Nysa, that he believed Dionysus to have preceded him in this region, and that the Macedonians found evidence of Dionysus here, namely, the ivy on Mount Merus, are not in doubt. All our main Alexander sources mention his visit, though Plutarch does not discuss Dionysus, and what Diodorus had in his account is unknown, as the Nysa episode lies in a lacuna between Chapters 83 and 84 of Book 17, though the Table of Contents indicates that he dealt with the episode. Arrian’s mode of discourse seems to indicate the level of his skepticism:59 5.1.3: Alexander’s arrival at Nysa (statement of fact), given in direct speech; 5.1.4–6: Alexander’s conversation with Acuphis about Dionysus in Nysa (in doubt), given in indirect speech (with direct therein); 5.2.1–2: Alexander’s wish that Dionysus had been in Nysa (statement of fact), direct speech.

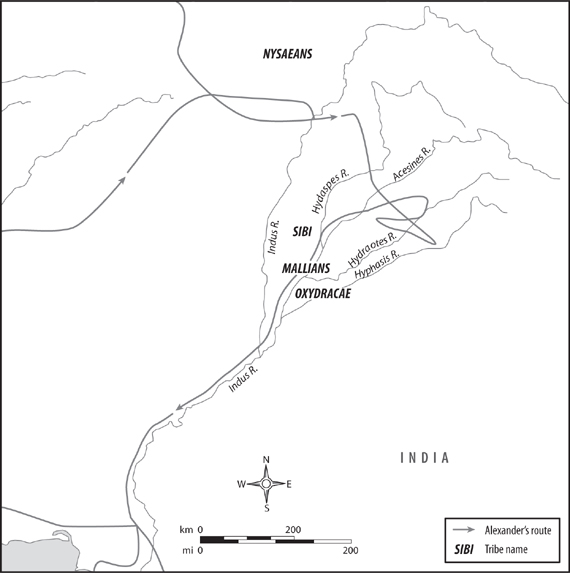

MAP 5.2

Alexander’s Campaign in India

Ultimately Arrian takes a neutral stand on these events. He mentions Eratosthenes’ incredulity about the “evidence” for the transit of Heracles and Dionysus through Asian lands, but he neither accepts such accounts at face value nor is willing to reject them outright. Instead, he says, “Let my own judgment of the accounts of these matters lie in the middle” (i.e., I draw no conclusion about them).60 On the other hand, Eratosthenes claims that such accounts are the products of Macedonian fabrication intended to flatter Alexander. Likewise, in the Indica, Arrian relates coolly the “evidence” of Dionysus and also Heracles in India that is presented by Megasthenes, who traveled to the court of Chandragupta as an envoy of Seleucus I. Arrian’s judgment about his reliability is mixed, but his conclusion about the evidence is that it amounts to Macedonian flattery, and he implies that Megasthenes’ accounts should be taken with a grain of salt.61 One reason for Arrian’s apparent indecisiveness is that the introduction of the divine into a discussion of historical realities changes the rules. The uncertainties that are more easily dismissed when matters are situated thoroughly in the mortal sphere are easier to account for “whenever the divine is added to the story.”62

Let us now be clear on what Eratosthenes rejects and Arrian has reservations about: (1) that Dionysus ever traveled in India (at least based on the “evidence” the Macedonians provide) and (2) as a consequence, that the Nysaeans ever invoked Dionysus as a link to Alexander. From our perspective, we must admit that because these facts are in doubt, Alexander’s use of kinship myth at Nysa is also in doubt, or at least in the way recorded by the sources. On the surface, it does seem rather unlikely that Indian peoples like the Nysaeans, the Oxydracae, and the Sibi would invoke Greek figures as their ancestors or founders. That would require some sort of Greek influence before Alexander’s arrival. The Greeks did serve the Persians in a variety of ways, as mercenaries in the armies, as architects and advisors, and so on. In anticipation of his conquest of India, Darius sent a Greek, Scylax of Caryanda, to survey the Indus valley and sail back through the Indian Ocean (Hdt. 4.44). The Persian Empire had opened up trade routes between East and West, allowing for increased contact between cultures. In the early fourth century, Ctesias, a doctor serving in the court of Artaxerxes I, gathered much information about India that came from merchants and wrote rather fanciful accounts of Indian ethnography and geography.63 We hear of movements of populations, as when Xerxes removed the Branchidae, the priests of Apollo at Didyma who surrendered to the Persians in 479, and whom Alexander later encountered in Sogdiana just after crossing the Oxus River. In the days of Cambyses, Greeks living in Barca in Libya were removed and settled in Bactria.64 Other Greek settlements may have been established in the eastern parts of the Persian Empire, putting them in proximity of the cultures in western India, though ultimately this is conjectural.65

So the possibility of interaction of Indians and Greeks in the Kabul Valley prior to Alexander’s arrival exists, but it is beyond the reach of proof. No wonder modern scholarship has tended to favor the view that the kinship diplomacy was a reflection of Macedonian initiative rather than Indian.66 If we follow the argumentation I have used above regarding Egypt and Persia, we should then wonder if Alexander would invoke a god who was not worshiped by the natives of western India, or perhaps the situation is reminiscent of Tyre in that it was Indra or Shiva whom the Nysaeans were invoking and that Alexander equated him with Dionysus. But, in fact, these precedents are of limited usefulness by this point in the campaign. In terms of the way Alexander made political use of myth in Greece and western Asia, the rules in force then likely had changed as he approached the valley of the Indus River.

The importance of Dionysus to Alexander at this point in the campaign cannot be denied. The god had long been revered in Macedonia and was especially the object of cultic devotion by Olympias.67 Not surprisingly, Dionysus, a god of wine, was popular among Macedonians, who were known for their devotion to heavy drinking. Moreover, Alexander had an increasing tendency to turn to alcohol as the campaign wore on.68 Meanwhile, his relationship with Dionysus took an interesting turn. Originally he worried about offending the god, as when he expressed remorse over the destruction of Thebes, Dionysus’ city. His murder of Cleitus in Sogdiana in 328 was attributed to the wrath of Dionysus, which Arrian noted appealed to Alexander as a way of shifting responsibility away from himself and to a divine agent.69

Dionysus, however, also became a rival of Alexander, especially as the king began to embrace more earnestly the idea of his own divinity. To surpass a god would be even more glorious than to surpass Philip or even Heracles. The unexpected presence of ivy in the frontier beyond Sogdiana and the Jaxartes River, as well as near Nysa, later seemed to confirm for the Macedonians that Dionysus had been there and that they were now passing the limits he had reached, especially as ivy had been noticeably absent in most of Asia.70 At least that was the propaganda. In any case, it may be that Alexander paid more attention to Dionysus in his later years than when the invasion first began, and his increased use of alcohol may partly account for it. But it was also a consequence of his turn toward deification, and that would seem to explain the unlikely kinship diplomacy at Nysa. Having given in to his delusions of godhood, the pragmatist who could reject the use of kinship myth in Persia became increasingly remote in India.71

While the preponderance of the evidence for Dionysus in India can be dated only after Alexander’s expedition, there was one sliver of a tradition that might have influenced him beforehand. The Macedonian court was home to the Athenian playwright Euripides during the reign of Archelaus (413–399). Alexander, who knew his Homer, was also likely to be familiar with two particularly pertinent plays of Euripides: the Bacchae and the Cyclops. First, Euripides has Dionysus say in the prologue of the Bacchae that he has traveled through Lydia, Phrygia, Persia, Media, Arabia, and other parts of Asia, all the way to Bactria before arriving at Thebes (14–23). It would not be surprising if it had been Euripides who fired Alexander’s imagination when he saw ivy not only in the direction of Bactria but well beyond, namely, in the Saka lands beyond the Jaxartes River, leading Alexander to conclude that he had surpassed the god in this part of the world.72 The ivy he found growing around Nysa would have had the same effect on him. Whatever the original Indian name of the town that surrendered,73 Alexander, under the spell of compelling evidence, brought with him the magical name of “Nysa,” long fabled to exist in distant parts of the world,74 and applied it to this Indian town. Or rather he did after he saw the ivy. But, as we shall see, the actual diplomacy itself may not have initially involved Dionysus. The relevance of the god may have become apparent only as an afterthought.

What the Cyclops allowed was a possibility for Alexander to be connected directly to Dionysus by descent. Early on in the play we find Silenus saying to the chorus of satyrs: “Can it be that you have the same rhythm to your lively dance as when you went revelling at Bacchus’ side to the house of Althaea, swaggering in to the music of the lyre?”75 As later sources attest, Dionysus rather than Oeneus was said to be the actual father of Deianira by Althaea.76 The implications are profound. Not only is Alexander in rivalry with Dionysus in the distant lands of Asia, but Alexander’s own greatness in reaching them (not to mention in subduing fierce Indian tribes) can be traced back to Dionysus as well as Heracles, given that Deianira is the mother of Hyllus, ancestor of the Temenids.77

It remains for us to uncover the actual circumstances of the kinship diplomacy as we consider how Alexander’s transformed consciousness might have effected it. Our sources say that the Nysaeans were the ones to suggest the Dionysian link. Could the people of “Nysa,” or whatever they actually called their city, have embraced the Greek god Dionysus and used their resulting link with Alexander to procure lenient treatment? Bosworth points out that Alexander received several envoys from the various Indian tribes, both while still in Sogdiana and on the eve of his invasion of India, including Taxiles and later his son Mophis or Omphis, who saw in their subservience to Alexander a hope of getting the better of their rivals, including in this case the powerful Porus.78

Through the interpreters, the Indians would have become acquainted with the peculiarities of Alexander’s personality and mindset, learning of his fixation on Dionysus and Heracles (from the coterie of court flatterers), as well as the controversies raging (perhaps quietly) in the Macedonian court about proskyn sis and so on. The interpreters would be “explaining Indian institutions to Alexander and expounding the peculiar customs of the invaders to visiting Indian delegations.” Somehow, the suggestion would have been made to the envoys (by the interpreters or by Alexander’s staff) that their tribes embrace Dionysus and Heracles as a basis for a petition of leniency from Alexander. The tribes would then be in a position to claim to have been visited once by Dionysus and Heracles, only now to be visited by Zeus’ “third son,”79 Alexander, at least according to the vulgate tradition, if not to sources closer to the events of 326.

sis and so on. The interpreters would be “explaining Indian institutions to Alexander and expounding the peculiar customs of the invaders to visiting Indian delegations.” Somehow, the suggestion would have been made to the envoys (by the interpreters or by Alexander’s staff) that their tribes embrace Dionysus and Heracles as a basis for a petition of leniency from Alexander. The tribes would then be in a position to claim to have been visited once by Dionysus and Heracles, only now to be visited by Zeus’ “third son,”79 Alexander, at least according to the vulgate tradition, if not to sources closer to the events of 326.

This explanation is plausible, but it is not the most solid foundation on which to rest the theoretical edifice that gives credit to the Nysaeans. Moreover, because it is the only foundation for this construct, we are left with considerable difficulties. First, the sources for the myth of Dionysus in India are not the likes of Ptolemy, Aristobulus, and Nearchus—though they may well have discussed Alexander’s belief in it. Instead, the legomenon at Arrian 5.1.4–6, from which the historian chose to distance himself, is based on a less reliable source, Cleitarchus,80 whose accounts of Alexander were tainted with inaccuracies arising from flattery and who lies behind most of the material provided in the so-called vulgate tradition, represented in the case of the Nysa episode by Curtius and Justin.81 Also possibly lying behind Arrian’s account in the Anabasis is Chares of Mytilene, whose reputation also does not fare well.82 As for Indica 5.9, here the source is Megasthenes, from whom Arrian distances himself at 6.1. Eratosthenes completely rejected the account, and Strabo adds his voice to the dissenters.83 Bosworth himself recognizes that Megasthenes “was developing the propaganda of Alexander’s court.”84 The opposing sides are clear enough, and we have seen this dichotomy before: popular belief and the viewpoint of more analytical writers.

The second difficulty in giving credit to the Nysaeans becomes apparent when one considers the evidence with the critical eye of someone such as Eratosthenes. The tradition has become muddled. On the one hand, Arrian says that Alexander wanted to believe that Nysa had been founded by Dionysus in part because “the Macedonians would not refuse further toil if they were emulating the toils of Dionysus.”85 This comment implies that the responsibility for the myth lies with Alexander. As noted before, it is presented in direct speech and suggests Arrian’s willingness to believe it. But it seems to contradict both the idea that the Nysaeans concocted the link and the alternative scenario that they were prompted either by interpreters or by officials in Alex-ander’s court to claim sungeneia with him. Responsibility for the invention of Dionysus in India suddenly becomes hard to determine. Would the Nysaeans have been observant enough in Alexander’s court to see the potential benefits of kinship diplomacy and concoct their Dionysian origins? Would the interpreters have been astute enough to make the suggestion, possibly recognizing similarities between Dionysus and their own god, either Indra or Shiva?86 Would Alexander’s staff have been able to do it without Alexander realizing the truth, that is, would they essentially have duped him?

The key, I believe, is the ivy that grew on Mount Merus. The ivy plays a prominent role in the narrative, but Alexander would not yet have seen it at the time of the negotiations with Acuphis. The path of least resistance then may be the following: rather than posit a connection between India and Dionysus that might have been made by Greeks or the Indians in the initial negotiations or suggest that the local name for the town sounded like “Nysa” to Greek ears from the start, we would do better to go with the evidence that is irrefutable, that the Macedonians saw some form of ivy growing near Nysa. As happened north of the Jaxartes, Alexander’s imagination was fired, and it was only at this point that he considered the possibility of Dionysus as the bond of commonality between the Nysaeans and the Macedonians, even as his ambition to surpass Dionysus flared anew. The rest of the evidence (the attributes of Indra or Shiva, the name “Nysa”) followed as a matter of course, all to give further credence to Dionysus’ travels. It benefited the Nysaeans as well, who were more than happy to believe whatever Alexander wanted to tell them as long as it meant they avoided the grim fate that so many other Indian cities had faced and would suffer yet. This is the beginning of the stories not only of Alexander’s kinship diplomacy at Nysa but of Dionysus’ Indian ventures, stories that then “snowballed,” as Bosworth has aptly described it, in the years, generations, and centuries that followed Alexander’s death.87

Alexander’s need for heroic and divine emulation may also provide the context for the other two known cases of kinship diplomacy in India. They come during Alexander’s savage campaigns down the Hydaspes Valley in the winter of 326/5, en route to the putative southern shore of Ocean, which the Greeks believed encircled the earth. Although it is possible that some sort of cultural interaction before Alexander’s assault might have led the Sibi to adopt Greek ancestors to save themselves, the probabilities here remain the same as in the case of the Nysaeans, that the Greek context was suggested by the Macedonians. Alexander encountered the Sibi around the confluence of the Hydaspes and the Acesines. The vulgate authors say that this people forestalled the usual massacre that other Indian tribes suffered by sending envoys to Alexander’s camp and offering their submission. Alexander gladly accepted it and declared independence for their city.88

Supposedly, the basis for their surrender and Alexander’s leniency was that the Sibi were descended from followers of Heracles. Diodorus says that their ancestors were established in their city by Heracles after he had failed to take Aornus. In Curtius’ version, they had been left behind because of disease and established themselves in their present site. Further, says Curtius, they showed signs of their Heraclid origins by dressing in skins and wielding clubs. This account, both of the claims of kinship and even of the visit itself, is not to be found in Plutarch or Arrian’s Anabasis. In fact, in the Indica Arrian attributes it, once again, to Macedonian fabrication, or at least to a confusion of different Heracleses, perhaps the Tyrian or Egyptian, rather than the Theban (5.12–6.1), an interesting stance given the more common belief that Heracles was widely traveled and that evidence of his visits could be found in distant parts of the world. Strabo echoes the rationalist’s sentiment, adding that the Sibae (as he calls them) branded cattle with a sign of the club.89 We may have a case in which characteristics of a local culture reminded Alexander of Heracles’ former presence, and he was happy to promote his presence, once again for his own glory.

Alexander encountered the Oxydracae during his campaign against their neighbors the Mallians around the confluence of the Hydaspes and the Hydraotes. While he recovered from the serious wounds he incurred after his fateful leap inside the walls of the Mallians’ city, he received the embassies of surviving Mallians and other tribes with the usual offers of submission. Though not claiming to be descendants of Dionysus or his followers, the Oxydracae did assert that they were entitled to their independence from Alexander, which they had preserved “from the time of Dionysus’ arrival in India to that of Alexander’s.” Consequently, because Alexander was like Dionysus, having also been born from a god, they would agree to the presence of a satrap.90 As Bosworth has shown, the latter comment suggests that they regarded their independence as having been bestowed initially by Dionysus, perhaps even in the capacity of a ktist s, or founder.91

s, or founder.91

Arrian’s account of their association with Dionysus carries as much weight as what Strabo had read in his sources, namely, that the Oxydracae, whom he calls the Sydracae, were descendants of Dionysus, as the presence of vines and the Bacchic characteristics of their royal processions indicate.92 Arrian’s account once again forces us to ask if an Indian tribe would have invoked a Greek god without prior Greek prompting. If we assume that the name “Dionysus” meant nothing to the Oxydracae, to salvage Arrian’s account we must assume that they employed Shiva or Indra, expecting that Alexander would respect their own god when they mentioned him in connection with their antiquity and nobility. An alternative is that we have to move away from Indian initiative and come back to a Greek recognition of Dionysus in a local god. Someone on Alexander’s side then communicates to the Oxydracae that they either mention Dionysus in connection with their antiquity (Arrian) or even cite him as an ancestor (Strabo). Yet, this seems to have been the first dialogue Alexander had with the Oxydracae, who had secured their wives and children in their strongholds and resolved themselves to resistance against the foreign invader and then later apologized to Alexander for having attempted no earlier parley.93

Thus, we face even greater difficulties than we did at Nysa. Under these circumstances, if the vines Strabo mentioned were genuine, Alexander may have thought of Dionysus as he passed through in 326/5, but any reference to sungeneia should again make us suspect later fabrication. Likewise, the reference to Alexander’s divine sonship in Arrian is a clear sign of flattery, likely the product of subsequent Macedonian traditions.

In sum, the story of Dionysus in India does not seem to have predated Alexander’s campaigns there. At most, we can say that they begin with Alexander himself and then take on new life after his death, as is the wont of the legends of great men. Alexander’s case demonstrates well the nature of popular belief in the ancient Greek world, which develops because the force of its momentum is often greater than the efforts of analytical writers like Eratosthenes to inhibit it. Both the stories of Alexander himself and the myths he likely embraced must be judged under difficult scholarly circumstances indeed. The transformation of kinship myth’s most famous practitioner from man to hero to god also transformed the way he used his myths. Alexander may well have become delusional in his last years, corrupted by power, succumbing to paranoia, or losing himself to alcoholism. The Alexander who killed Philotas, Cleitus, and Callisthenes, who introduced proskyn sis and alienated his army in other ways, who pushed his soldiers beyond endurance, and who possibly demanded deification is not the Alexander we know who secured Thessaly’s allegiance partly on the basis of mythical kinship.

sis and alienated his army in other ways, who pushed his soldiers beyond endurance, and who possibly demanded deification is not the Alexander we know who secured Thessaly’s allegiance partly on the basis of mythical kinship.

Therein lies the problem: the Alexander we know. He has become romanticized over and over, a construct remade a thousandfold. We can at least say that Greek myth always imbued his world, from beginning to end, even if we seek some “turning point” to account for his change in behavior and goals.94 Alexander abandoned kinship myth after the Battle of Issus in 333 when it could no longer serve his ends, a recognition of the practical limitations of kinship diplomacy, which required acceptance of the proposed sungeneia to mollify a newly conquered city. If he took it up again in 326, his divine pretensions were what motivated it, and the purpose became his glorification. Like the myths themselves, the stories of their use by Alexander in India rose to new heights of myth-making.

As we draw together the evidence from the literary sources, Arrian reminds us that even the intellectual writers could slip into the mode of popular belief that generally contrasted with the critical approaches taken by his ilk. Like Strabo, Arrian seemed to understand the power of tradition to perpetuate questionable claims, so much so that he acknowledged its hold even on him as he decided to maintain the custom of calling the Hindu Kush the Caucasus, despite a full acknowledgement that such practice might go back to Macedonian attempts to glorify the scope of Alexander’s journey.95 Alexander’s legend itself is like Greek myth in that new versions of “the story” eventually took on a new life of its own. We have seen this in cases in which old myths were given a new spin for political gain, with the resulting variation surviving into our later literary sources.

Through it all has been the progression of credulity from the analytical writers to their audiences. The application of kinship myth with non-Greeks demonstrates the point well. Herodotus’ audience would have had no reason to reject his description of Xerxes’ citation of an Argive heritage. Thucydides’ consternation about Tereus may have arisen from a general Athenian perception of the Thracians embracing him as an ancestor. And while Alexander seemed at first to understand the limitations of myth as a political tool, he too, it seems, embraced the unlikely identity of a descendant of Dionysus to reach his goals in India. Myth, including kinship myth, allowed the Greeks to make sense of the periphery of their world. As such, it was naturally hellenocentric.

As anyone would do, the Greeks expressed matters in their own terms, as when Greek heroes served to demonstrate the relationship of peripheral peoples with the hellenic center. That is fundamental to understanding kinship diplomacy with non-Greeks and is much of the basis for rejecting Areus’ diplomacy with the Jews, which would have him invest Abraham with the same authority as a hellenic hero. For both Areus and the Pergamenes, Abraham was not suitable as a link of kinship with the Jews. However, Abraham does allow a strong case to be made for Jonathan’s overtures and, further, shows that the Jewish High Priest understood Greek kinship diplomacy. If his purpose was to express a certain identity by asserting Jewish distinctiveness, for the benefit of either the Greeks or the hellenized Jews (or both), he would naturally have chosen someone like Abraham as the paradigm of the virtues of his people.

We have seen a variety of political activity (a handy rubric for both military and diplomatic acts) in which myth, kinship or otherwise, has come into play. Most prominent is treaty formation, which itself occurred in a variety of circumstances. Some treaties led to alliances with a goal of preemptive mutual defense, as in Athens and Thrace and Herodotus’ putative proposal of Xerxes to the Argives. Other treaties (often informal) arose in the aftermath of conquest, as happened repeatedly, on the basis of kinship myth and otherwise, during Alexander’s campaign. The overlap of alliance formation and territorial conquest in this case bridges the line I drew to divide Chapter Four from the previous one, a categorical convenience rather than a reflection of reality. We have also seen myths invoked by speakers looking to influence a political decision, as Solon (according to Plutarch) did before a group of Spartan judges and Archidamus (according to Isocrates) did before an assembly of anti-Theban allies. This type of setting lies behind some of the proclamations recorded in inscriptions mentioning sungeneia, though an important difference is that in the latter cases, the objective was not the justification of territorial possession, as we shall see in the next two chapters.

Conquests perhaps provide the biggest challenge for us, in terms of understanding how myth came into play. Did the conquerors really promote their Heraclid descent among the inhabitants of the regions they subdued, or tried to subdue? In the case of Dorieus and Pentathlus, the sources hint at it by making note of their special heritage. But it is the historian’s notation. He does not actually say that these would-be founders themselves employed myth in their martial and diplomatic endeavors. In the case of Alexander, on the other hand, references to his use of myth are clear. But even here we must have a care: as was likely the case with the accounts of Alexander in India, reference to heroic descent could have reflected traditions or even propaganda that was transformed into tradition only after the actual diplomacy. In these cases, however, I have argued that the references, even if merely incidental remarks, deserve serious historical consideration: that is, we can presume that our ancient sources would not have made these remarks unless they had before them evidence that kinship and related myths were actually invoked and employed by the players in their narratives, such as Dorieus.

Discussion of conquests has also brought another important distinction to light, one that is to be made, though with care. The basis of the arguments made by Archidamus, Solon, and (perhaps) Dorieus was not kinship as such with the current inhabitants of Messenia, Salamis, and Eryx, respectively. We do not hear of descendants, in the present, of Heracles in Eryx and Messenia or of the sons of Ajax in Salamis.96 That is not to say that there was no such notion, but we have no extant stemmas of lineage from the legendary founder or putative ancestor to the leaders in these regions at the times under discussion. Kinship, therefore, seems less applicable than the simple argument that the aggressors have a right to control the land and its population. The right stems from a legal grant of sorts, given by the heroes to their descendants in the aggressor states, rather than from kinship with the conquered inhabitants in the present. This argument lay behind Alexander’s justification of his overlordship in Thessaly as well, but here the other methodology was also brought to bear. Through both his father and mother, Alexander could produce stemmas that not only linked him with Heracles and Achilles but also linked the Thessalians with both of those heroes. Anthony Smith’s “genealogical” model applies here, except that the pedigrees linking the Aleuadae to Aleuas, Thessalus, Achilles, or all three may not have been fully developed, the connection perceived more abstractly.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, kinship and related myths were expressions of identity. This was the central concern in Athens and Megara in their contest over Salamis. Such a mindset accounts for the great deal of mythopoeic activity connected to Spartan colonies. But here, too, we must be cautious. Did Messenia have the same status in Spartan thinking as Salamis in Athenian, and especially in Archidamus’ argument? Or was invoking Messenia’s Heraclid identity merely a ploy of Archidamus to facilitate an immediate objective? We might argue that the similar basis of Spartan legitimacy in both Laconia and Messenia supports the former view, for the Spartans’ claim to their own territory derives from the most ancient tradition of the Return. Archidamus’ case is built on a tradition that had been embraced by an entire community in the archaic period. To be sure, part of the purpose was to justify the Dorian presence in the Peloponnesus.

Yet Tyrtaeus’ invocations to his fellow Spartans would ring hollow if that were the only purpose of the story of the Return of the Heracleidae. As an individual, Archidamus will certainly have his own motives for using this tradition. Isocrates, Aeschines, Demosthenes, and every other orator knew well how personal objectives could be procured by means of emotional appeal to deeply held beliefs. The distinction is important. Dorieus is another individual. Does Sparta’s Heraclid identity come into play in his bid for Eryx? It does so only as a means to an end. Though his venture was perhaps officially sanctioned by Sparta, he was out to make his name in a way he could not when the throne went to Cleomenes. His claims as a Heraclid had particularly expedient motivations. To a large extent, the same holds true for Alexander. On the other hand, myths involving genealogy and kinship were certainly expressions of identity when developed, embraced, and employed by communities. This will be especially apparent in our study of the inscriptions that communities produced on or soon after occasions of kinship diplomacy.