————— SIX —————

Epigraphical Evidence of Kinship Diplomacy

Paradigmatic Inscriptions

Our consideration of inscriptions referring to kinship or other close relationships, often by the terms sungen s/sungeneia or oikeios/oikeiot

s/sungeneia or oikeios/oikeiot s, brings us also to the hellenistic period that followed the death of Alexander in 323. The swell in epigraphical evidence at this time could be the result of the chance survival of our evidence, but we have reason to believe that a shift occurred in the purposes that kinship myth served, though not in the basic motivation to use myth for political gain, and that the use of kinship myth correspondingly increased.

s, brings us also to the hellenistic period that followed the death of Alexander in 323. The swell in epigraphical evidence at this time could be the result of the chance survival of our evidence, but we have reason to believe that a shift occurred in the purposes that kinship myth served, though not in the basic motivation to use myth for political gain, and that the use of kinship myth correspondingly increased.

The hellenistic period was an age of empires. The polis was still there, but its heyday had passed. The political fortunes of the Greek world, which now extended into the former dominions of the Persian Empire, were largely controlled by kings, beginning with those former generals of Alexander who took power and territory for themselves. The uncertainty that arose, in terms of both political identity and the vicissitudes of fortune, gave rise to anxieties that kinship diplomacy helped to address. We have less concern with territorial possession and more attention to alliances, safety for travelers, exchange of citizenship rights, and so on. Most importantly, I hope to show that the inscriptions of this period give evidence of the highly volatile nature of hellenic mythopoesis—that is, the capacity of many Greeks to accept variations and even versions newly invented, possibly by educated politicians, as part of the diplomatic proceedings. In other words, communities often provided a mythological justification of their kinship by reconciling their local myths, even given contradictory details in their respective communal traditions (as at Pergamum and Tegea; see Chapter Seven) or by using different charter myths for different occasions, as suggested by the practices of Samos.

The voice of the people, so to speak, may well be the one we hear in some of these epigraphical records. The issuers of these decrees were cities across the Aegean basin and beyond. The evidence suggests that the governments were largely democratic, if not the sort of radical democracy known to fifth- and fourth-century Athens. In his analysis of city decrees, P. J. Rhodes, building on the work of D. M. Lewis, noted the importance of a popular assembly, or ecclesia, in the political decisions of most hellenistic states.1 In many cases, it was the demos who were largely responsible for most political and administrative appointments, maintaining financial and other public records, receiving foreign embassies, and approving foreign treaties. There was undoubtedly much variation in this state of affairs, and we must keep in mind the vital role that continued to be played by financially and politically prominent individuals. This is especially true in diplomatic proceedings, in which such individuals were likely to be better informed about international matters than the rest of the citizenry. That leaves us facing considerable limitations in assessing who proposed the mythical links.

The specific circumstances in which the polis’ charter myths were invoked in the diplomacy are generally beyond our reach; therefore, we are not well informed on whether such myths were invoked by the citizenry (perhaps in the deliberations of the ecclesia) or injected into the diplomatic proceedings by men of prominence—whether in the ecclesia or in a more private exchange with representatives of the other state—whose education allowed them to see possible links to the charter myths of the other community. If the connections proposed below are the correct ones, however, we see Hellen and his sons, panhellenic figures of enormous significance to the Greeks, playing a significant role in hellenistic kinship diplomacy. Knowledge beyond the inherited oral traditions of the community was not needed for ordinary citizens to see possible patterns linking their state to another, once they were made aware of that state’s charter myths through the agencies of more informed citizens or perhaps in the course of the diplomatic exchanges in the assembly.2 Transactions invoking kinship were usually ratified by popular vote,3 whatever the origin of the myth employed. In addition, members of the elite would be the ones to take the credit for the successful completion of a diplomatic venture that brought some advantage to the city. In the relationship between the elite and the community, let us recall that in more democratic societies, it was the latter on which the honor of the elite depended.4 We are reminded, then, of the use of myth not only for civic identity but for the enhancement of prestige, along the lines of the mythopoesis behind the familial traditions of archaic and classical elite families and behind the political machinations of such ambitious individuals as Dorieus, Peisistratus, and Cimon.

A RHAPSODE IN IC I.XXIV.1

Unfortunately, the process of introducing myth into the diplomatic proceedings is beyond our reach. It is tantalizing to consider the following example as paradigmatic of kinship diplomacy in general, but we lack the evidence to know how much the case of Menecles was typical. This rare glimpse of diplomatic proceedings involving kinship comes in an inscription dated to the early second century BCE, part of a series found at Teos in which the cities of Crete recognized Teos as asylos, or “inviolable.” The point of these decrees was to insure protection of Tean travelers from Cretan piracy. Most of the inscriptions use kinship terminology (sungen s, sungeneia, and other terms) to describe the relationship between the Teans and the Cretans.5

s, sungeneia, and other terms) to describe the relationship between the Teans and the Cretans.5

In this context, IC I.xxiv.1 honors a Tean ambassador named Menecles, a rhapsode who, kithara in hand, performed for the assembly of Priansus local Cretan epic cycles, as well as works by the well-known poets Timotheus of Miletus and Polyidus of Selymbria (lines 7–13).6 These performances served several purposes. Most immediately, they were to explain the basis of kinship between the Cretans and the Teans. Furthermore, by performing Cretan poets alongside Timotheus and Polyidus, Menecles was endorsing Crete’s traditions as part of the shared hellenic culture.7 The other inscriptions found at Teos are themselves the evidence of the success of the Tean mission to Crete, suggesting that Menecles’ performances were influential in the decisions of the Cretan assemblies. These assemblies comprised Greeks with a less precise conception of myth. Depending on the extent of the democratization of Crete, it was perhaps by the votes of these citizens that the Teans’ request for asylia was approved.8 IC I.xxiv.1, therefore, could potentially give us a valuable look at how myth was actually used in diplomatic proceedings if only we had other similar evidence for comparison.

This inscription is certainly more typical, however, in that neither it nor any of the others in the series reveals what the basis of the kinship is. Indeed, this is the great challenge we face when using inscriptions as evidence for kinship diplomacy, for, with very few exceptions, no inscription out of the hundred or so employing kinship terminology gives us this information. We may know that the parties in question are sungeneis and that the basis of the sungeneia is mythical in nature, but the inscription does not fill in an important blank for us: does the sungeneia originate in this account or in that one, with this personage or with that one? In short, the mythological explanation is missing from the inscribed text. Such an ellipsis, of course, was as natural for the commissioners of the document as the indirect references to Perses in Aeschylus’ account of Xerxes’ origins. For them there was no gap.

But the debate over the series from which IC I.xxiv.1 comes reveals the problem for modern researchers. Jones and Curty presumed that the thalassocracy of Minos explains the link, while Elwyn looked to Athamas son of Oenopion of Crete, a reconstruction criticized by Lücke.9 Lücke’s complaint was that Elwyn started with the assumption that Athamas must be the link between the Cretans and the Teans because he is the only one the ancient sources have produced who could fit the bill, and from there she devised her reconstruction of Cretan-Tean sungeneia. Lücke made the further point that other sources, no longer extant, might also have revealed the link enshrined in local Cretan myth and reproduced by Menecles. Indeed, we should wonder why Minos would not feature highly in the performance of Menecles, given his importance as a local hero. Lücke’s criticism must be taken seriously, and so we are left wondering how useful literary sources can be in reconstructing the kinship mentioned in inscriptions.

Elwyn’s analysis was indeed flawed insofar as we cannot be sure that the Cretans themselves had embraced a figure named Athamas son of Oenopion as an ancestor. She cited Pausanias 7.4.8, which is problematic because Pausanias read of Oenopion and his sons in a history of Chios, written by a fifth-century poet named Ion, who was from that island rather than from Crete. We have no way of knowing if Ion provided the foundation myth we need to fill in the gap in IC I.xxiv.1. More importantly, he was not a local source for Cretan myth. It would not be an unreasonable conjecture because Athamas’ father Oenopion was a son of Dionysus and Minos’ daughter Ariadne. But the source for this tidbit is Diodorus 5.84.3, and so again we are not dealing with a local Cretan writer and cannot be sure about Diodorus’ source. Moreover, we have nothing at Pausanias 7.4.8 to connect with Teos.

Earlier, Pausanias had mentioned a different Athamas who founded Teos with Minyans from Orchomenus. No patronymic is given, but Pausanias says that he was descended from Athamas son of Aeolus. He may have read this in Anacreon of Teos, whom Strabo cites as his source for the same founder.10 At least here we have a local expression of identity, but to connect Teos and Crete, we are forced to conflate what are most likely two separate figures. That, too, is not unprecedented in Greek political mythmaking, and in fact we shall consider a comparable case. But the evidence for that lies in an inscription from Xanthus that provides all the mythological clues we need. Conflating the two Athamas figures requires stitching together sources, including nonlocal ones, which raises the uncertainty over this reconstruction to an uncomfortable level.

Caution is clearly called for as we tackle the problem of reconstructing the basis of kinship claimed by states that have no historical link that we can discern, links for which only myth can provide the answer.11 Nevertheless, it is in local myth that we may find the control that we need. Ion of Chios is of limited usefulness as a source of Cretan myth, but we would be more confident if we were to call upon Ion to provide evidence of local Chian myth, as we shall later. A study of epichoric or local myth, in particular myths of foundation, can shed much light on the mythological context of the epigraphical evidence. This sort of account was extremely important to a city, whether its foundation was ancient, as with Miletus, or fairly recent, as in the case of Antioch-on-the-Maeander, a Seleucid colony. Foundation myths recounted the origins of a city and thus served as a vessel of identity. It stands to reason that this is the identity a community would most likely express in interstate diplomacy. Thus, the probability that we have correctly identified the mythological basis of kinship increases dramatically if we posit an epichoric myth for the state initiating the diplomacy.

To that end, Pausanias becomes a valuable source for study. In the second century CE this writer traveled throughout the Greek world and recorded what he had learned of the antiquities of many communities in a sort of travel log known as a peri g

g sis—not antiquities merely in the sense of physical remains, such as temples and statues but also in the sense of local stories about the foundation and early history of these cities. Although these stories were centuries old, Greek cities preserved them, including variations of more well known accounts, far into the Roman period. Pausanias had direct access to these local myths through informants and home-grown literature. I will discuss his reliability as a source of local myth in more detail in the next chapter, but for now suffice it to say that my method will be as follows: if his source is demonstrably local, Pausanias will be deemed a reliable recorder of local myth, which I will argue lies behind the claim of kinship between the communities mentioned in the inscription under study. But before we explore those cases, there is much to learn from the two inscriptions that do reveal the mythological basis of kinship. These decrees, I.v. Magnesia 35 and SEG XXXVIII.1476, can serve as models for the others and give confidence that the local myths to be cited later are in fact the correct ones.

sis—not antiquities merely in the sense of physical remains, such as temples and statues but also in the sense of local stories about the foundation and early history of these cities. Although these stories were centuries old, Greek cities preserved them, including variations of more well known accounts, far into the Roman period. Pausanias had direct access to these local myths through informants and home-grown literature. I will discuss his reliability as a source of local myth in more detail in the next chapter, but for now suffice it to say that my method will be as follows: if his source is demonstrably local, Pausanias will be deemed a reliable recorder of local myth, which I will argue lies behind the claim of kinship between the communities mentioned in the inscription under study. But before we explore those cases, there is much to learn from the two inscriptions that do reveal the mythological basis of kinship. These decrees, I.v. Magnesia 35 and SEG XXXVIII.1476, can serve as models for the others and give confidence that the local myths to be cited later are in fact the correct ones.

I.V. MAGNESIA 35: MAGNESIA-ON-THE-MAEANDER AND CEPHALLENIAN SAME

I.v. Magnesia 35 is one of about sixty inscriptions found by the Germans in the agora of Magnesia-on-the-Maeander and that now reside in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.12 These consisted of responses to an initial Magnesian request by various states and hellenistic kings. As we learn especially from I.v. Magnesia 16, in 221/0 the Magnesians attempted to enhance the prestige of its festival for its arch getis, a sort of patron goddess and founder, Artemis Leucophryene. The context is a recommendation of asylia for Magnesia by the Delphic oracle. Earlier, the Magnesians had consulted the oracle to inquire about the meaning of a manifestation of Artemis in their city. Apollo required the Magnesians to honor him and Artemis and suggested that the Greeks should treat Magnesian territory as “sacred and inviolable” (

getis, a sort of patron goddess and founder, Artemis Leucophryene. The context is a recommendation of asylia for Magnesia by the Delphic oracle. Earlier, the Magnesians had consulted the oracle to inquire about the meaning of a manifestation of Artemis in their city. Apollo required the Magnesians to honor him and Artemis and suggested that the Greeks should treat Magnesian territory as “sacred and inviolable” ( ) (lines 4–10). The Magnesians decided that they should hold games with stephanitic prizes in her honor to fulfill this obligation (lines 16–24).13 Though the Magnesians sent out announcements of the games and calls for the city’s inviolability, the local festival attracted little attention (line 24), probably because they did an inadequate job advertising the oracle and may have limited the scope of their invitations to Greek cities closer to them in Asia Minor.14

) (lines 4–10). The Magnesians decided that they should hold games with stephanitic prizes in her honor to fulfill this obligation (lines 16–24).13 Though the Magnesians sent out announcements of the games and calls for the city’s inviolability, the local festival attracted little attention (line 24), probably because they did an inadequate job advertising the oracle and may have limited the scope of their invitations to Greek cities closer to them in Asia Minor.14

Later, in 208/7, they tried again to promote their festival and stephanitic games, perhaps more widely, certainly with greater expenditure, and with more emphasis on the oracle (lines 28–29). An important distinction from their first attempt was that now the Magnesians were seeking “isopythic” status for their games, which would make them equal in prestige to the Pythian Games at Delphi itself, enhancing their standing among the city-states of the hellenistic world, with special attention to nearby rivals Miletus, Ephesus, and Didyma.15 The inscription concludes that this second set of embassies was much more successful, with widespread acknowledgement of the sanctity of the games and the inviolability of Magnesia (lines 30–35). Having the isopythic status of their games acknowledged was a particular coup for the Magnesians. This was achieved in part through the help of kings, but we can also presume the excellence of the envoys’ arguments to justify other states’ acceptance of Magnesia’s requests. In the case of I.v. Magnesia 35, that justification was mythological in nature.

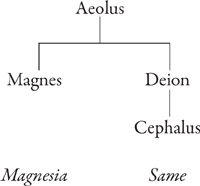

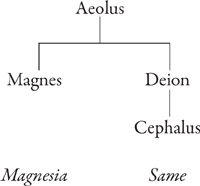

I.v. Magnesia 35 contains the decree of Same on Cephallenia, with the island’s other three cities (Pale, Cranii, and Pronni) listed as subscripts. It reveals that, in making their case, the Magnesians cited accomplishments of their ancestors, praise among poets, the aforementioned Delphic oracles,16 and finally the kinship (or relationship) (oikeiotatos) between the Magnesians and the Cephallenians that stemmed from the kinship (sungeneian) of their eponymous ancestors.17 Figure 6.1 is a diagram of the link: the Magnesians looked to Magnes, son of Aeolus, as their founder, while Cephalus is the eponym of the island of Cephallenia and appears on their coins.18 Cephalus’ father is Deion, another son of Aeolus and thus brother of Magnes, so this account has it.

FIGURE 6.1.

Magnesia-on-the-Maeander and Cephallenian Same

For both parties we have genuine expressions of local identity, although these figures are known from a number of sources. The variations that occur are intriguing. Magnes is an ancient figure known to the oral poets, but I.v. Magnesia 35 is the earliest attestation of Magnes as son of Aeolus, a version that later gained ascendancy and became known to Apollodorus (Lib. 1.7.3). This patronymic is significant because it makes available to the Magnesians a genealogical link to the people of Same. The possibility exists, however, that Magnes’ Aeolid descent was also known to Homer. Comparison with the alternative Hesiodic version bears interesting results. In the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women, Magnes and his brother Macedon are sons of Zeus and Thyia, Deucalion’s daughter. In that work the brothers are associated with the region around Pieria and Olympus (F. 7 MW), which is not surprising, as Pieria and Olympus lie in southern Macedonia. On the other hand, in the Catalogue of Ships, Homer associates the descendants of Magnes with the vicinity of Peneus and Pelion (Il. 2.756–758), in the region of southeastern Thessaly known as Magnesia. In the Catalogue of Women these regions are occupied by descendants of Aeolus, as West has noted,19 and they continue to be in later accounts, as in Strabo.20

Two possible answers to this question present themselves. As with other parts of Homer’s Catalogue (we have noted the Athenian case), a later interpolation may lie behind the mystery at lines 756–758 in Iliad 2. Another possibility is that these lines preserve some awareness of a tradition predating Homer and finding expression in only two other places: Apollodorus and I.v. Magnesia 35. In the same sentence in which he identifies Magnes as one of Aeolus’ sons, Apollodorus speaks of Aeolus ruling Thessaly (Bibl. 1.7.3). In Thessaly might lie the origin of this figure Magnes, as distinguished from others such as the wind god. As J. M. Hall interprets the Hesiodic treatment of him and Macedon, their connection to the family of Hellen on the mother’s side (through Thyia) allows those who invented these figures to reject their ethnic identity as Hellenes. Hall attributes the invention to the Thessalians, who wanted to deny the hellenicity of their Magnesian and other rivals in Thessaly.21 The Magnesians who eventually migrated to Asia Minor to found Magnesia-on-the-Maeander sometime in the Dark Ages22 may well have brought Magnes with them in their foundation stories.

We can imagine that, afterwards, a tradition developed in areas of Asia Minor or the eastern Aegean that made Magnes the son of Aeolus. This was the version that centuries later made its way to Apollodorus’ handbook and was perhaps known to Homer, who traced the origin of the Magnetes, commanded by Prothous in the Trojan War, to the homeland of Aeolus and his people.23 The local myth to which I.v. Magnesia 35 refers, therefore, may well have been quite old.24 Even so, we have no solid evidence to support this reconstruction. We are just as likely dealing with a hellenistic invention, perhaps even for the occasion of Magnesia’s diplomacy with Same. In fact, as we shall see, other examples from the hellenistic period show that the invention of genealogical stemmas on the occasion of a diplomatic venture not only was practiced but readily embraced. With I.v. Magnesia 35 itself as our earliest evidence, it would be perfectly reasonable to date Magnes’ Aeolid descent to the third century.

By contrast, the connection of Cephallenia’s eponymous founder to Aeolus is easier to trace in early sources. Cephalus’ father Deion would seem to have been designated a son of Aeolus as far back as the eighth century, and probably earlier, if the reconstruction of line 28 of Fragment 10a in the Hesiodic corpus, in the Catalogue of Women, is correct.25

Cephalus’ patronymic is well attested. The story of Cephalus and Procris goes back at least to oral tradition. There is an allusion to it in the Epigonoi and later in the writings of Hellanicus, a mythographer of the mid fifth century. A slightly earlier mythographer, Pherecydes, is the earliest extant source recounting some measure of the tragic tale of Procris’ death at her husband’s hand. In all these sources, and also the oral Nostoi,26 Cephalus is acknowledged as son of Deion.27 The account of how Cephalus gave his name to Cephallenia is told by Apollodorus, which probably derives from the Catalogue of Women and possibly from Pherecydes.28 Cephalus participated in Amphitryon’s campaign against the Teleboans of the Echinades islands (off the coast of Aetolia). This was the campaign to avenge the brothers of Alcmena, which Electryon was prevented from waging when Amphitryon accidently killed him. For that act he was exiled to Thebes, where he sought the aid of Creon for the forthcoming expedition. The Theban king replied that he would render the aid if Amphitryon would rid Thebes of the Teumessian fox. As often the case, this animal was special in its ferocity and in the fact that its fate was always to elude its pursuer. Amphitryon knew of another animal touched by fate, a hunting dog acquired by Procris from Minos and now in Cephalus’ possession. This dog was destined to catch whatever it pursued. Cephalus agreed to help Amphitryon if later he could reap spoils from the latter’s war on the Teleboans. When the dog that always caught its prey chased the fox that always eluded its pursuer, resolution only came when Zeus turned both animals into stone.29 Finally, Amphitryon attacked the Echinades islands, defeated the Teleboans, and gave possession of one of the islands to Cephalus (Lib. 2.4.6–7). Whether this last detail, the naming of the island, is also from the Catalogue remains uncertain, though there is no reason to reject it.

In any case, this Cephalus was certainly well established in panhellenic tradition by the end of the third century. The Magnesians need not have looked far to find their link with the peoples of Same and the other cities of Cephallenia, whether by “Magnesians” we mean the voting public or members of the elite class who were well equipped to manipulate the myths. Again, we are left in the dark about the actual procedures. But the results are clear enough. The Cephallenians accepted Magnes as uncle of Cephalus. They (the people, the leaders, or both) may have been aware of some tradition for which we cannot find solid evidence, or they accepted him on the word of the Magnesians. Especially at the hands of the more credulous, such mythmaking allowed the Cephallenian citizenry to accept Magnes as son of Aeolus even if they had never heard that patronymic applied to him before. The Cephallenians may not have been aware of the epichoric traditions of Magnesia-on-the-Maeander (at least before the diplomacy) and could not judge their authenticity. In fact, as further evidence will adduce, “authenticity” did not always require antiquity.

Even the invention of Magnes’ Aeolid lineage specifically for the occasion of Magnesia’s quest for asylia need not have been a barrier to the Cephallenians’ recognition of that asylia. From an elite point of view, the invention was perhaps a tried-and-true diplomatic formulation, but its embrace by the populace was required for the diplomacy to succeed. What Aeolus, son of the Greeks’ collective ancestor, did was open a door for the Magnesians and the Cephallenians, who each found a way to connect their own local myths to the great panhellenic stemma that began with Hellen, somewhat in the same vein as the seventh-century Spartan innovations that connected their royal houses to the Heraclid collectivity. Whether through citation of old legends or manipulation on the spot, it was a tactic that recurred in hellenistic diplomacy.

SEG XXXVIII.1476: CYTENIUM AND XANTHUS

As with I.v. Magnesia 35, SEG XXXVIII.1476 presents some puzzles, even though it provides the mythological basis for the kinship. The inscription is from a stele found in a sanctuary of Leto in Xanthus in Lycia, a place of prominence for such an object because Leto was the founder and protector (arch getis) of the city. It acknowledges the aid the Xanthians rendered to the people of Cytenium in Doris in 206/5 BCE. Following an earthquake that destroyed Cytenium’s walls twenty years earlier, the Aetolian League, of which Cytenium was a member, encouraged its Dorian allies to seek financial help to rebuild the walls. The legation from Cytenium also sought aid from Ptolemy IV and Antiochus III. As they had with Xanthus, the Cytenians cited links of sungeneia with the kings.30

getis) of the city. It acknowledges the aid the Xanthians rendered to the people of Cytenium in Doris in 206/5 BCE. Following an earthquake that destroyed Cytenium’s walls twenty years earlier, the Aetolian League, of which Cytenium was a member, encouraged its Dorian allies to seek financial help to rebuild the walls. The legation from Cytenium also sought aid from Ptolemy IV and Antiochus III. As they had with Xanthus, the Cytenians cited links of sungeneia with the kings.30

SEG XXXVIII.1476 stands out as the longest and best preserved inscription recording kinship diplomacy. What follows is only a small portion. Here, the Xanthians recall the circumstances of the diplomacy and the two mythological arguments the Cytenians had made to justify it:

They request us, recalling the kinship that exists between them and us from gods and heroes, not to allow the walls of their city to remain demolished. Leto [they say], the goddess who presides over our city [arch getis], gave birth to Artemis and Apollo amongst us; from Apollo and Coronis the daughter of Phlegyas, who was descended from Dorus, Asclepius was born in Doris [that is, the land of the Dorians]. In addition to the kinship that exists between them and us (deriving) from these gods, they also recounted the bond of kinship [symplok

getis], gave birth to Artemis and Apollo amongst us; from Apollo and Coronis the daughter of Phlegyas, who was descended from Dorus, Asclepius was born in Doris [that is, the land of the Dorians]. In addition to the kinship that exists between them and us (deriving) from these gods, they also recounted the bond of kinship [symplok tou genous] which exists between us (deriving) from the heroes, presenting the genealogy between Aiolus and Dorus. As well, they indicated that the colonists sent out from our land by Chrysaor, the son of Glaucus, the son of Hippolochus, received protection from Aletes, one of the descendants of Heracles: for [Aletes], starting from Doris, came to their aid when they were being warred upon. Putting an end to the danger by which they were beset, he married the daughter of Aor, the son of Chrysaor. Indicating by many other proofs the goodwill that they had customarily felt for us from ancient times because of the tie of kinship, they asked us not to allow the greatest of the cities of the Metropolis to be obliterated. (lines 14–33)31

tou genous] which exists between us (deriving) from the heroes, presenting the genealogy between Aiolus and Dorus. As well, they indicated that the colonists sent out from our land by Chrysaor, the son of Glaucus, the son of Hippolochus, received protection from Aletes, one of the descendants of Heracles: for [Aletes], starting from Doris, came to their aid when they were being warred upon. Putting an end to the danger by which they were beset, he married the daughter of Aor, the son of Chrysaor. Indicating by many other proofs the goodwill that they had customarily felt for us from ancient times because of the tie of kinship, they asked us not to allow the greatest of the cities of the Metropolis to be obliterated. (lines 14–33)31

The Xanthians go on to say that they agreed to the request (lines 38–42), acknowledging the sungeneia (line 46). However, they could only manage to give the Cytenians five hundred drachmas of silver (lines 62–65). Appended to the initial document of 73 lines are documents from the Aetolian League and a second letter from Cytenium. References to Ptolemy and Antiochus in these items reveal the extended scope of the mission. While most of the other inscriptions to be examined involve eponymous representatives of ethnic groups (e.g., Hellen, Aeolus, and Dorus) more directly, here, in both the divine and the heroic links, the Cytenians’ Dorian heritage looms more subtly in the background of the complex argument. In both cases, the Cytenians have made innovations in older stories.

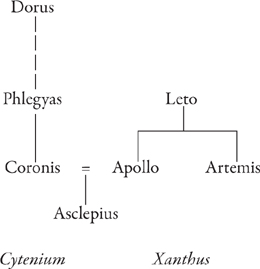

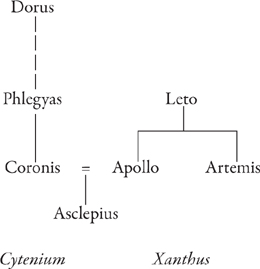

FIGURE 6.2.

Cytenium and Xanthus (Divine Connection)

First, although Dorus is specifically mentioned in the sungeneia deriving from the gods, in this case the key figure is Asclepius (Figure 6.2). One might expect it to be sufficient to mention only the healer god because his relationship with Apollo, the son of Xanthus’ patron goddess, and his descent from Dorus through Coronis, daughter of Phlegyas, provided the necessary connection. However, the Cytenians take the extra step to have Asclepius born in their homeland, Doris, a location not found in any previous account.32 This invention would probably not have given the Xanthians pause because there were already a number of places that claimed to be Asclepius’ birthplace, including Tricca in Thessaly and Epidaurus. The point is obviously to strengthen the association of Asclepius specifically with Cytenium itself.

In the end, however, the Cytenians seem to have judged the divine link to be in need of supplement. As the terminology at lines 15 and 20–21 indicates (sungeneias), kinship of gods that were closely associated with two cities also meant kinship between the citizens of those cities. Normally that would be enough, but we also have a heroic link that provides not only a more direct genealogical link between the peoples but also a precedent for the requested act of philanthropy. In presenting this link, the Cytenians performed a remarkable feat of mythopoesis. It looks as though the Cytenians both made adjustments to Dorian epichoric myths in Doris and the Peloponnesus and added new elements to Xanthian local myth.

Of course, the figure Glaucus son of Hippolochus goes all the way back to Homer. Glaucus—there is evidence of a civic cult to him and Sarpedon in Xanthus (TAM II.265)—allows Xanthus to be connected with the Trojan War, always a venerable source for charter myths, as we shall see in the case of Phygela later. The connection enhanced the prestige of the elite classes in Xanthus and other Lycian cities and also reflects the increasing hellenization of Lycia in the hellenistic period.33 Given the peculiar nature of the detailed revisions discussed below, we are likely dealing with mythological manipulation at more learned hands.

An innovation comes with Chrysaor, an enigmatic figure who appears in myth in multiple forms: the most famous is the offspring of Medusa and the progenitor of various monsters, including Geryon,34 making Chrysaor hardly a heroic figure. The Lycian Chrysaor, meanwhile, may predate the Xanthian inscription, though there is no way to tell. This curious figure, or a closely related one, was prominent in southwest Asia Minor, however. The name was associated with Zeus, whose shrine was the focus of the Chrysaorian League in Caria.35 This federation included the city of Alabanda, which became known as Chrysaorian Antioch sometime between 275/4 and 250.36 But the name Chrysaor is also associated with a mortal, the eponymous founder of the league. One would not expect him to be associated with the son of Medusa, and yet on Antioch’s coins, along with Apollo Isotimus, is found Pegasus, Medusa’s other child by Poseidon.37

Whatever the full story of this Chrysaor, according to Bousquet, the Cytenians mention him because their embassy also traveled to Caria to seek aid from Antiochus III, who was there at the time.38 Invoking him in this way suggests that the Carian and the Lycian Chrysaors are the same, and Stephanus of Byzantium provides further evidence of this (on which more soon). In light of this state of affairs, the argument for a Xanthian invention of Chrysaor son of Glaucus is, to me, more plausible than a Cytenian. The heroic Chrysaor, already a home-grown figure in neighboring Caria (see below), was probably adopted in Lycia from that direction or possibly had come from Lycia to Caria. In any case, his descent from Glaucus is most likely part of the local myths of Xanthus. However, it is impossible to tell if this Xanthian innovation was already ancient by 206/5 or contemporaneous with the Cytenian embassy of that year.

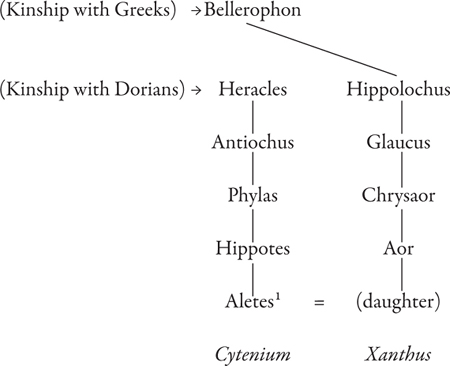

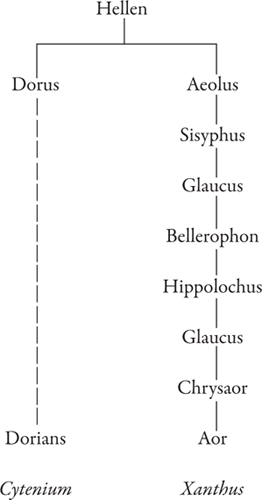

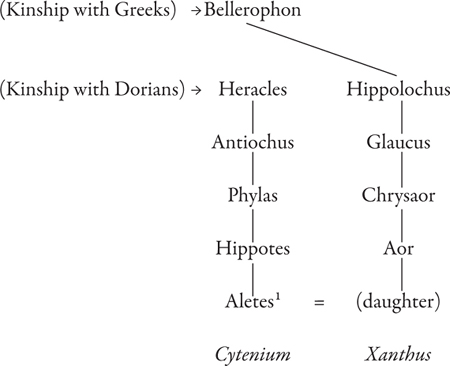

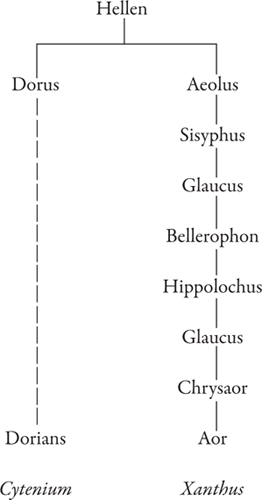

Meanwhile, as a link of kinship, Chrysaor’s usefulness to the Cytenians was limited. The stemma, shown in Figure 6.3, is as follows: Chrysaor son of Glaucus son of Hippolochus son of Bellerophon. On this basis alone, there is no substantive connection to the Dorians, to say nothing of the Cytenians themselves. The emphasis seems to be merely on the Xanthians’ connection to the Greeks of the original homeland, of which Bellerophon was one of the great heroes. The inscription does, however, offer the following clue: “composing the genealogy of Aeolus and Dorus.”39 To connect the two parties through the sons of Hellen, one must go past Bellerophon to his ancestors (Figure 6.4): Bellerophon son of Glaucus son of Sisyphus son of Aeolus. This link is a little more direct (by focusing on an actual link of consanguinity rather than a representative of the Greek race, namely, Bellerophon), even if it must reach farther back in time.

1. Aletes’ lineage is found at Apollod., Bibl. 2.8.3. See also Paus. 2.4.3. Salmon 1984: 39 suggests that Aletes’ descent from Antiochus rather than from Hyllus, the ancestor of Temenus and his brothers, is evidence that the account of Aletes’ conquest was originally independent of that of the Return of the Heracleidae. The former may have been dealt with by Eumelus in the eighth century.

FIGURE 6.3.

Cytenium and Xanthus (Heroic Connection)

To complicate matters further, the elder Glaucus would have probably been the more appropriate one to cite as Chrysaor’s father. On the one hand, Chrysaor was known to an Apollonius of Aphrodisias (date unknown) as an important colonizing figure in Caria.40 Basing his account on Apollonius, Stephanus of Byzantium provides information about a Carian city called Chrysaoris, which was “the first of the cities founded by the Lycians.”41 A Lycian Chrysaor is implied here and by extension his descent from the Homeric Glaucus (son of Hippolochus), who along with Sarpedon leads the Lycians in the Iliad (2.876–877). On the other hand, in reference to another Carian city, Mylasa, Stephanus mentions the eponymous founder, Mylasus, and gives the following lineage for him: son of Chrysaor son of Glaucus son of Sisyphus son of Aeolus.42 This pattern recurs in early Greek myth: a king, himself a ktist s, or founder (e.g., Chrysaor), has sons who go on to found more cities (e.g., Mylasus). As with accounts of the Ionian migrations, this aetiology of Mylasa is probably quite old, apparently from a source other than Apollonius, unless the latter had confused his Glauci.

s, or founder (e.g., Chrysaor), has sons who go on to found more cities (e.g., Mylasus). As with accounts of the Ionian migrations, this aetiology of Mylasa is probably quite old, apparently from a source other than Apollonius, unless the latter had confused his Glauci.

FIGURE 6.4.

Cytenium and Xanthus (Dorian-Aeolian Link)

Both versions are apparently Carian in origin. If Mylasus was a local hero in Mylasa, then his father might well have been also. Conceivably, the formulation of Chrysaor as son of Homer’s Glaucus that took place in Cytenium or more likely in Xanthus in the hellenistic period (if not before) was a revision of this earlier version (a Chrysaor only two generations removed from Aeolus) that still survived in one of Stephanus’ sources. In other words, someone in the hellenistic period moved Chrysaor further down the genealogical tree so that he could be more closely associated with the Lycians, a Chrysaor who was originally Mylasan.

Whether the Cytenians were aware of or concerned about these contradictions is ultimately academic, for they came up with a link that was more efficacious than the others: an even more shadowy figure named Aor. As noted above, his tale further served the purpose of providing a precedent for the aid the Cytenians sought. The inscription suggests that Chrysaor sent out his son Aor to colonize other places.43 Aor came to Greece, apparently not to Doris itself because the king who saved him had already “started out” from there. This king, Aletes, was a descendant of Heracles and led a faction of the Dorians to capture Corinth (Paus. 2.4.3), perhaps around the same time that the other Heraclids under Temenus took the rest of the Peloponnesus.44 In any case, Aletes came to the rescue of Aor and his people during a war and afterwards married Aor’s daughter. Aside from the genealogical link this marriage afforded—the people of Aor were now part of the tribe of Dorus—the Cytenians saw in this scenario the perfect precedent. Their ancestors had come to the aid of the Xanthians, and now it was time to return the favor.

Bousquet was unable to find a history behind Aor and concluded that he was a Cytenian fabrication on the occasion of the kinship diplomacy.45 However, an inscription from Delos holds a possible clue: although the city that issued the inscription cannot be identified due to the present condition of the stone, Robert suggested that it was issued by Corinth’s neighbor Phlius because of a reference to a civic tribe called the Aoreis, perhaps derived from the local hero Aoris, son of Phlius’ founder Aras.46 Nicholas Jones, however, argues for Corinth, pointing out that her colony Corcyra may have had a tribe called Aworoi. Christopher Jones favors the latter interpretation, which he feels is confirmed by the Xanthian inscription.47

Either way, we can have some confidence in a tradition of a Dorian Aor, whether from Corinth or Phlius, of whom the Cytenians were aware. A reasonable conclusion is that the Cytenians brought together for the first time the Xanthian figure Chrysaor and the Corinthian figure Aor, shamelessly putting a spin on Xanthus’ local myth. Perhaps the Cytenian ambassadors, in making their case to the Xanthians, argued that the Sisyphid Chrysaor was also known in the old Dorian lands. The argument would not have been difficult for the Xanthians to accept because Chrysaor alone was obviously known in a variety of forms across the Greek world. It is a testament to the persuasiveness of the Cytenians’ case that the Xanthians agreed to pay something in spite of considerable financial hardship.48 They could not offer the vast sums that Ptolemy and Antiochus could, but they clearly deemed their sungeneia with Cytenium important enough to spare five hundred drachmas.

s/sungeneia or oikeios/oikeiot

s/sungeneia or oikeios/oikeiot s, brings us also to the hellenistic period that followed the death of Alexander in 323. The swell in epigraphical evidence at this time could be the result of the chance survival of our evidence, but we have reason to believe that a shift occurred in the purposes that kinship myth served, though not in the basic motivation to use myth for political gain, and that the use of kinship myth correspondingly increased.

s, brings us also to the hellenistic period that followed the death of Alexander in 323. The swell in epigraphical evidence at this time could be the result of the chance survival of our evidence, but we have reason to believe that a shift occurred in the purposes that kinship myth served, though not in the basic motivation to use myth for political gain, and that the use of kinship myth correspondingly increased. ) (lines 4–10). The Magnesians decided that they should hold games with stephanitic prizes in her honor to fulfill this obligation (lines 16–24).

) (lines 4–10). The Magnesians decided that they should hold games with stephanitic prizes in her honor to fulfill this obligation (lines 16–24).