8

The Paradoxes of Time Travel

Time travel stories have become one of the staple narratives of science fiction. In the twentieth century, the idea that we could travel in time became a real possibility with the advent of the special and general theories of relativity. As soon as scientists began to treat time travel as a live possibility, a number of critics voiced their concerns over the coherence of travel into the past. Travel into the past, it was suggested, would inevitably lead to paradoxes that threaten to ‘tear apart the spacetime continuum’ or force us into some otherwise horrible mess. This view of time travel was voiced by the famous science-fiction author Isaac Asimov, who once wrote:

The dead giveaway that true time-travel is flatly impossible arises from the well-known ‘paradoxes’ it entails. The classic example is ‘What if you go back into the past and kill your grandfather when he was still a little boy?’ … So complex and hopeless are the paradoxes … that the easiest way out of the irrational chaos that results is to suppose that true time-travel is, and forever will be, impossible. (Isaac Asimov, Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection, Harper Voyager, 2003, pp. 276‒7)

In this chapter we will consider the case for Asimov’s position. Is time travel really impossible? Does travel into the past inevitably result in a world torn apart? The answer is straightforward: no. But of course, as we shall see, the devil is in the details.

8.1. What is Time Travel?

Before we can look at the paradoxes of time travel in earnest, we need to first consider what time travel is. We want an account that specifies under what conditions someone or something travels in time: we want the necessary and sufficient conditions for some instance of travel to be time travel. That is to say, borrowing some terminology from Chapter 1, we want a constitutive theory of time travel. That’s because we are not asking what actual time travel is like (if there is any) ‒ whether it occurs through a wormhole, or via a machine like the TARDIS, or in some other manner. We are only asking what it would take for something to count as being time travel. With a better sense of the nature of time travel in hand, we can then turn to the potential for catastrophe that it supposedly entails.

8.1.1. External Time and Personal Time

We know what it is to travel through space. We do it every day when we head to the café to get coffee. We leave one location in space and travel to some other location. Our travel takes time. We can calculate the speed by which we move by seeing how much time elapses, per amount of spatial distance we cover. But what does it mean to talk about travelling in time? In the broadest sense, travel through time involves leaving one temporal location and arriving at some other temporal location. According to this broad definition, we are all travelling through time. Each of us leaves one temporal location and arrives at some other temporal location. Each of us left yesterday, and arrived at today, and consequently we time travelled from yesterday to today. That, however, is not the kind of time travel in which philosophers are interested. Indeed, that sense of time travel is better known as persistence, a phenomenon we considered in the previous chapter. In what follows, when we talk of time travel we will mean time travel other than ordinary persistence. Call this interesting time travel.

Lewis’s seminal 1976 paper ‘The Paradoxes of Time Travel’ offers a useful way both to conceptualise interesting time travel and to mark the difference between interesting time travel and mere persistence. Lewis introduces a distinction between external time and personal time. External time is just time. The external temporal distance between two events is the temporal distance between those events. So the temporal distance between December 2015 and December 1985 is thirty years of external time.

Personal time, by contrast, is not really time at all. Personal time is really a measure of change. While the traveller is travelling, he gains new memories, gets hungry, eats, digests food, his fingernails grow, his cells die, and so on. These changes typically take a certain amount of external time. For instance, it typically takes about one month of external time for fingernails to grow 3mm. So suppose Fred, the time traveller, gets into a time machine in January 2017, and while in the time machine his nails grow 3mm. If all of the rest of the changes Fred undergoes are roughly those you and I would undergo through a period of a month (if he accrues a month’s worth of memories, eats a month’s worth of dinners, and so on) then we will say that one month of personal time has elapsed for Fred. If, at the end of his journey, Fred gets out of the time machine and is in January 2000, then it has taken him one month (of personal time) to travel seventeen years (of external time).

According to Lewis, a journey counts as interesting time travel only if there is a disparity between personal time and external time. Notice that in the case of persistence there is no disparity between personal time and external time: it takes each of us one day of personal time to travel one day of external time.

Personal Time: n minutes of personal time elapses, iff the amount of change that occurs is the same as the amount of change that would typically occur in n minutes of external time.

Lewis held that the disparity between personal time and external time is a necessary condition for a journey to count as (interesting) time travel. We can put this as follows:

Time Travel Necessary Condition 1: Necessarily, a journey counts as time travel only if there is a disparity between the elapsed personal time of the traveller during that journey, and the external time travelled during that journey.

There are two ways for personal time and external time to come apart. First, the amount of personal time that elapses might be different from the amount of external time that elapses. Second, the temporal relations between events in personal time might come apart from the temporal relations between events in external time, without the amount of time actually differing. This second way for personal time and external time to differ might be difficult to understand. So here’s an example to help. Suppose that Fred gets into a time machine at 2pm on 2nd January 2015, and steps out of the time machine on 1st January 2015. In terms of external time, he has travelled one day into the past. Suppose, however, that his journey in personal time itself takes a day. In this case there is no disparity between Fred’s personal time and external time with respect to the amount of time that has passed. There is, however, a disparity with respect to the temporal relations between the start of Fred’s journey and the end of his journey in the two times. In external time, the start of Fred’s journey occurs after the end of his journey. In personal time, the start of Fred’s journey occurs before the end of his journey. This helps to bring out one of the important features of personal time: personal time always ticks forwards even when external time ticks backwards.

In cases of persistence there is no disparity of either kind. If a time traveller sits in her office and waits for an hour, then the start of her journey and the end of her journey are an hour apart in external time. But so too for her personal time: she has to wait for an hour. Moreover, the start of her journey is before the end of her journey in external time. Again, so too for her personal time: the start of her waiting period in personal time happens before the end of that period.

The distinction between personal time and external time therefore provides us with a way to differentiate persistence from interesting time travel. In cases of persistence, external time and personal time are in accord in the two ways discussed. In cases of time travel, external time and personal time are out of sync in one of the two senses described.

What else does Lewis think is necessary for a journey to count as time travel? Well, in order for anyone to count as travelling from place A to place B, it needs to be that the person who leaves A is the same person who arrives in place B. After all, Sara can’t travel to Singapore from Sydney by staying in Sydney and having a friend of hers in Thailand travel to Singapore. Nor would she count as having travelled to Singapore if she was killed in Sydney, and, by pure fluke, someone just like her was created in Singapore. So a second necessary condition for a journey to count as time travel is that the person at the beginning of the journey is the same person as the person at the end of the journey. Indeed, since objects that are not persons can travel in time (we could send an urn back in time) any object, O, counts as travelling in time only if the object that departs on the journey, O, and the object that arrives at the end of the journey, O*, are one and the same object.

Time Travel Necessary Condition 2: Necessarily, a journey counts as time travel only if the traveller who departs and the traveller who arrives are one and the same traveller.

Lewis thinks that these two necessary conditions are, jointly, sufficient conditions for a journey to count as time travel. That is, he thinks if both of the necessary conditions are met, then the journey is an instance of time travel.

Time Travel Sufficient Condition: Necessarily, a journey counts as time travel if (a) there is a disparity between the elapsed personal time of the traveller during that journey and the external time travelled during that journey, and (b) the traveller who departs and the traveller who arrives are one and the same traveller.

As we saw in the previous chapter, what it takes for an object at one time to be the same object as some object at another time is controversial. But, with the tools of Chapter 7 in hand, we can say that something counts as going on a journey only if the thing that leaves and the thing that arrives are the same persisting thing (leaving it open exactly what it takes for an object to persist).

8.1.2. Forwards Travel versus Backwards Travel

Backwards time travel is time travel towards the past. Forwards time travel is travel towards the future. Much of the discussion within philosophy has focused on backwards time travel. But forwards time travel is just as interesting. Indeed, according to Einstein’s theories of general and special relativity forwards time travel is relatively straightforward.

In order to understand time travel in the context of special and general relativity, we need to complicate the distinction between personal time and external time somewhat. According to the special and general theories of relativity, the temporal distance between events depends upon one’s relative state of motion. This has a range of important implications, some of which were discussed in earlier chapters. The crucial point is that this variance in temporal distance gives rise to an important relativistic phenomenon: the phenomenon of time-dilation. As we increase our speed, external time slows down. So, for instance, suppose that we place a clock on Earth and we place a clock on a spaceship that is travelling away from the Earth at half the speed of light (150,000 km/s). Suppose that the clock on the spaceship records that 15 minutes has passed. In the time it takes the clock on the spaceship to record the passage of 15 minutes, the clock on Earth will have recorded the passage of approximately 23 minutes. As we speed up, the discrepancy grows exponentially. This means that if one were to travel at very close to the speed of light in a spaceship travelling on a roundtrip away from the Earth, minutes or hours may have passed for the occupant of the spaceship, while thousands of years might have passed on Earth.

Because the temporal distance between events depends on one’s relative motion, special and general relativity recommend multiplying external time. There is no longer just one external time. Rather, because the temporal ordering and temporal distance between events depends on relative motion, there are many external times, each of which is assigned to an inertial frame of reference: a perspective on the universe that is in constant motion. Accordingly, we can now differentiate between external time 1, external time 2, external time 3 and so on. Each observer still has only a single personal time. It is just that a single observer’s personal time may correspond to different external times as they change their relative state of motion. It doesn’t follow from this, however, that personal time and external time are out of sync through such shifts in relative motion. So long as the personal time of an observer within a frame of reference always corresponds to the external time within that frame of reference, then personal time and external time remain in sync. Which is to say that if one speeds up and external time slows down, then so long as one’s personal time also slows down to match the external time, the two are kept in sync. And, indeed, that is precisely what happens.

This is just to say that persistence has its analogue in a relativistic setting. So too does the interesting type of time travel. The notion of interesting time travel identified above, however, needs to be modified somewhat. Recall the necessary condition that Lewis placed on time travel:

Time Travel Necessary Condition 1: Necessarily, a journey counts as time travel only if there is a disparity between the elapsed personal time of the traveller during that journey, and the external time travelled during that journey.

This definition is fine for pre-relativistic time, but needs to be updated for relativistic time. We continue defining time travel in terms of discrepancies between personal time and external time; however, in a relativistic context we must understand these discrepancies with respect to a particular external time. If one’s personal time is out of sync with external time 1, then one has time travelled with respect to external time 1. It is compatible with one’s personal time being out of sync with external time 1, however, that it remains in sync with some other external time, such as external time 2.

To grasp the idea, suppose that Bert and Ernie are identical twins living on Earth. Suppose we put Bert into a rocket that travels at high speed away from the Earth, reaches a distant destination, then turns and heads back towards Earth. When Bert arrives back on Earth and gets out of the rocket, he has aged six years, while Ernie has aged ten years. So the twins are no longer the same age! How can this be? Well, when Bert speeds away from the Earth his external time slows down relative to Ernie’s personal time. Bert’s personal time syncs with his new external time, and so this slows down too. That means Bert ages more slowly compared to Ernie. When Bert returns to Earth, his external time shifts back to Ernie’s external time. His personal time syncs back up with Ernie’s external time, and the two start ageing at the same rate once again: a year older for Ernie will be a year older for Bert, despite the new age difference between the two twins. With respect to Ernie’s external time, Bert is a time traveller. Although Bert’s personal time re-syncs with Ernie’s once he arrives back on Earth and he starts ageing at the same rate, Bert’s personal time remains somewhat out of sync with Ernie’s external time in a global sense. According to Bert’s personal time, only six years have passed when he arrives back on Earth. According to Ernie’s external time ten years have passed. So there is a discrepancy between Bert’s personal time and Ernie’s external time.

It is worth noting that there is also a discrepancy between Ernie’s personal time and Bert’s external time. For Ernie, ten years have passed in his personal time. In Bert’s external time, however, only six years have passed. Does this make Ernie a time traveller with respect to Bert’s external time? According to Lewis’s account of what it is for someone to be a time traveller, the answer is ‘yes’. But you might think not. If you have the view that Ernie is not a time traveller with respect to Bert’s external time, then you might try to modify Lewis’s definition to handle this sort of case. We leave it to the reader to consider strategies for how this might be achieved.

Forwards time travel of the kind just described is relatively easy. In fact, it’s been done: astronauts on the international space-station are travelling fast enough that they are shifted into a distinct external time relative to us here on Earth. Those astronauts are travelling micro-seconds into our future. Backwards time travel, by contrast, even in the context of the special and general theories of relativity, is much harder to achieve. This has a lot to do with the causal structure of the universe according to relativity. Travel into the past requires retro causation: the causation of events in the past by events in the future.

Retro causation, although compatible with general relativity, is quite difficult to achieve. Still, it can happen. If our world is correctly described by relativity then it is possible for there to be closed time-like curves. A closed time-like curve is the path of an object through spacetime where that object’s path returns to its original position. One way in which an object can have a path that returns to its starting point is if spacetime itself is curved. To see this, pick up a piece of paper and turn it into a cylinder by connecting its two ends. Now trace a path around that cylinder. The path can begin at one location on the cylinder, and, despite always going in the ‘same’ local direction, will end up back where it started. We can imagine that a sub-region of spacetime is folded up in just this way and thus that time curves back on itself. Then an object that travels along this curved spacetime for some period will, for some portion of its lifetime, travel along a closed time-like curve. During that period the object will always seem to be moving forwards on a straight path, but by doing so it will travel back to an earlier external time. Since the existence of closed time-like curves is entailed by some solutions to Einstein’s field equations, we know that such curves can exist. So far, however, no one has ever found a region of spacetime that is folded in this way (though such folding may occur near a black hole).

8.1.3. Possibility: Logical, Metaphysical and Nomological

As we noted, philosophers tend to focus on backwards time travel. This is because backwards time travel is thought to give rise to various unnerving paradoxes. In a relativistic setting, however, the alleged paradoxes of backwards time travel can be formulated just as easily for forwards time travel of the kind described. Philosophers tend to focus on backwards time travel, however, as it is easier to elucidate and discuss the kinds of paradoxes that are thought to arise. Moreover, in the backwards time travel case, these paradoxes will arise even for non-relativistic universes, which may not be true for the forwards-looking versions of the paradoxes. At any rate, let us follow tradition here and focus on the backwards case.

One of the questions philosophers ask about time travel is whether it is possible. As we have seen, possibility is a modal notion, which is often understood in terms of possible worlds. The idea is that something is possible if there is some world at which that thing occurs. Something is impossible if there is no world at which it occurs. So, for instance, it is impossible that there are square circles, because there is no world in which there are square circles. To capture this idea philosophers often say that square circles are logically impossible. That is because there is something contradictory about the very idea of a square circle, since a square circle would need to be both circular and not circular, and being both P and not P is a contradiction. So X is logically impossible if X’s obtaining would result in a contradiction obtaining. Since contradictions are impossible ‒ there are no worlds in which both P and not P ‒ anything that entails a contradiction is thereby logically impossible.

Often when philosophers ask whether time travel is possible they are asking whether it is logically possible. They are asking whether there are any worlds in which there is time travel (backwards time travel, that is). That is the question we will consider in the next section.

At other times, philosophers ask whether time travel is metaphysically possible. Sometimes metaphysical possibility is taken to be the broadest kind of possibility there is. Understood as such, the sphere of the metaphysically possible worlds is the same as the sphere of the logically possible worlds ‒ namely, all of the worlds. Sometimes metaphysical possibility is defined by the set of worlds that share the same metaphysical truths as our world (i.e. truths about the nature of reality; truths that are captured by or enshrined within our best metaphysical theories of the world). This is what we will mean by metaphysical possibility. If one thinks that all worlds share the same metaphysical truths, then one thinks that the sphere of the metaphysically possible worlds is the same as that of the logically possible worlds. But if one thinks that some worlds have different metaphysical truths from our world, then one thinks that some worlds are logically possible, but not metaphysically possible. Hence philosophers who ask about the metaphysical possibility of time travel are asking whether the metaphysical truths are consistent with time travel.

Finally, philosophers sometimes ask whether time travel is nomologically possible. Then they want to know whether time travel is consistent with the laws of nature; that is, whether, out of all of the possible worlds that share the same laws of nature as our world, any of those worlds contain time travel.

As we have already seen, as far as we know, time travel is permitted by the special and general theories of relativity. Of course, it doesn’t follow that time travel is nomologically possible since, for all we have said so far, it might be that time travel is logically impossible, or metaphysically impossible. If so, then it must also be nomologically impossible. So in order to know whether time travel is nomologically possible we need to know whether it is logically possible, and, if it is, whether it is metaphysically possible.

8.2. Is Time Travel Logically Possible?

Let’s start by considering whether time travel is logically possible. On the face of it you might think it’s obvious that time travel is logically possible: after all, there doesn’t seem to be anything contradictory in the idea of travelling backwards in time. Yet until Lewis’ 1976 paper, it was often assumed that backwards time travel is logically impossible. The reason for this is that backwards time travel was thought to be something that could bring about contradictions, and since contradictions are impossible, so too, it was thought, time travel must be impossible. The grandfather paradox argument (see below) is one instance of an argument of this kind, designed to show that time travel is logically impossible.

The Grandfather Paradox Argument

[P1] Time travel is logically possible (assumption to be rejected).

[P2] If time travel is possible, then there is a possible time traveller who travels back in time and kills his grandfather before his father is conceived.

[P3] If the time traveller’s grandfather is killed before his father is conceived then the time traveller’s father is never born, and so neither is the time traveller.

[P4] So if the time traveller kills his grandfather before his father is conceived, then the time traveller does not exist.

[P5] If the time traveller kills his grandfather before his father is conceived, then the time traveller exists.

Therefore,

[P6] If time travel is possible, there is a possible time traveller who both exists and does not exist.

[P7] There is no possible time traveller who both exists and does not exist.

Therefore,

[P8] Time travel is not possible.

The argument appears compelling. It is surely true that if the time traveller travels back in time and succeeds in shooting his grandfather ‒ call him young grandfather ‒ before his father is conceived then the time traveller both exists and fails to exist. The time traveller exists because he shoots young grandfather and non-existent things cannot shoot anything. On the other hand, if the time traveller shoots young grandfather, then he himself will never be born, and hence he does not exist. So premises [3] through [7] look plausible. But [P2] also looks plausible. On the assumption that even a few time travellers travel back in time and try to kill their young grandfathers, it seems pretty likely that at least one of them will succeed. Hence we have a demonstration of the claim that time travel is impossible.

In response, Lewis argues that the grandfather paradox argument does not show that time travel is impossible. Rather, it shows that no one kills young grandfather. Lewis thus denies [P2] of the argument. It does not follow, he says, from the fact that time travel is possible, that it is possible for anyone to kill their young grandfather. For there is another option: the time traveller simply fails to kill their young grandfather whenever they try. What happens if a time traveller attempts to kill their young grandfather? Who knows? What we do know is that the attempts fail. Either the time traveller loses their nerve, or the gun jams, or the traveller suffers a stroke, or is prevented by a passing police officer, or the traveller accidentally kills the wrong person, or any of a host of other things happen; but what does not happen is a successful killing of young grandfather. But there is nothing contradictory about this: people try, and fail, to kill other people all the time. So the grandfather paradox argument merely shows that no time traveller ever brings about a contradiction; but of course that is true.

One might remain worried. After all, what motivates [P2] in the first place is the fact that it seems as though each of us can kill our own young grandfathers if we try. Indeed, it seems that each of us is as able to kill our own young grandfather just as easily as we might kill some random stranger at the mall. And if each of us can do something, we expect that many of us will succeed in doing that thing. If we collectively went out to malls and attempted to kill young people we would expect some of us to succeed. So too we expect that if we travel back in time to kill our young grandfathers, we would kill some of them. But according to Lewis anyone who attempts to kill their young grandfather has to fail. There are just some things that time travellers can’t do, and killing their grandfathers before their fathers were conceived is one of those things. If that is right, however, then it would seem we both can and cannot kill our grandfathers. We can kill our young grandfathers in just the same way that we can kill anyone; we cannot kill our young grandfathers because of the peculiarities of time travel. But that’s another paradox! So something has gone wrong.

Lewis’ response to this worry is to distinguish two senses of ‘can’. There is, he says, a sense in which each of us can kill young grandfather. Consider how we usually assess what it is that each of us can do. We consider our capacities, at a time, and this tells us whether we can do something or not. So, Sara can eat toast rather than cornflakes tomorrow for breakfast (assuming both are available) because she is fully capable of turning bread into toast and eating it. In this sense of ‘can’, each of us can kill young grandfather. Notice that when we are assessing what we can do, we do not include in the assessment future facts about what actually happens. Suppose we are assessing whether Sara can eat toast tomorrow morning for breakfast. Suppose also that, in fact, tomorrow she eats cornflakes. If we ask whether she can eat toast tomorrow given that she eats cornflakes, the answer would seem to be no. Given that she eats cornflakes, she can’t eat toast. Her eating toast is not consistent with her eating cornflakes.

Likewise, Sara’s killing young grandfather is not consistent with young grandfather living to a ripe old age and fathering her father, who fathers her. So, conditional on her grandfather not dying as a youth, she cannot kill him, just as conditional on her eating cornflakes tomorrow, she can’t eat toast. Nevertheless, in the ordinary sense of ‘can’ she can kill young grandfather, just as she can eat toast tomorrow. It is just that in fact, in both cases, she doesn’t: she does not eat toast, and she does not kill young grandfather. So relative to one set of facts, she can kill baby grandfather, and relative to another, she cannot. So there is no further paradox concerning the concept of ‘can’. More importantly, the relevant set of facts is really the set according to which she can kill young grandfather, because that’s the set of facts that we typically use to assess claims about what she can do. She can kill young grandfather, but she won’t.

We have, then, an explanation for why it is that [P2] seems to be true. [P2] trades on the idea that because each of us can kill young grandfather, in the ordinary sense of ‘can’, then some of us would, in fact, kill baby grandfather. But therein lies the mistake, argues Lewis. Each of us can, but none of us will. Still, one might still be left with a queasy feeling. For one might think that what Lewis tells us about the usual sense of ‘can’ is just misleading. One might think that the usual sense of ‘can’ is one in which, if one can do something, then if one were to try sufficiently often, one would, or might, succeed in doing that thing. So, for instance, Sara can eat toast for breakfast. Notice that were she to try to eat toast, then she either will, or might, succeed. Equally, if she kept trying to eat toast, and kept failing, she would surely eventually conclude that she cannot eat toast. She would conclude that she is not free to eat toast. So a remaining worry has it that even if what Lewis has shown is that time travel is possible, there is still a puzzle about time travel and free will. For killing young grandfather is not like eating toast at all. No matter how many times any of us tries to kill young grandfather, we will fail. This raises the problem of freedom, to which we return in section 8.5.

8.2.1. The Second Time Around Fallacy

It is tempting to conclude that although no time traveller will succeed in killing young grandfather, a time traveller might succeed in killing someone to whom he is not related, even if that person did not die at that time, in that manner, the ‘first time around’. Here is the thought. Suppose that the first time around, Frank grew up in the 1940s, lived to a ripe old age of eighty-nine, and died a peaceful death in 2016. Suppose, too, that Melanie, a time traveller, married Frank’s son, Dave, and that Melanie very much regrets this decision. Divorce seems like a lot of hassle, so instead she decides to travel back in time and kill Frank before Dave is conceived. Imagine that Melanie succeeds in killing Frank and therefore succeeds in making it the case that Dave is never conceived. Then the first time around, before the time travel, Frank lived to a ripe old age, and the second time around, after Melanie travelled to the past, Frank dies young and childless. Since Melanie is not related to Frank, her killing of Frank does not seem to generate any paradox.

Nevertheless, many philosophers think that what we just described is impossible. Such philosophers think that changing the past in this fashion is impossible, and that the story we just told commits the second time around fallacy. It is a fallacy, on this view, because there is no second time around. There is no way things were, the first time, prior to the time traveller arriving in the past, and a different way things are, the second time, after the time traveller arrives in the past. Why so?

In order for something to change, it needs to be one way and then some other way. In ordinary cases of change things change when they are one way at one time, and some other way at some other time (this is the at-at conception of change discussed in Chapter 1). For example, suppose that on Monday at 2pm Annie’s mass is 21.2kg (Annie is a dog). Suppose she wants to change her mass. She won’t do this by trying to make her mass different at Monday at 2pm. Instead, she will try to make her mass less, or more, than 21.2kg at times later than Monday at 2pm. But notice that in order to change the past we need to change some past time from being one in which Frank is alive to being one in which Frank is dead. How do we do that? The obvious suggestion is that a time needs to go from being one way at one time to being another way at another time. But no time can itself undergo change. Change is what happens to things in time, by things being different at different times. Times themselves cannot change their properties, for there is no dimension along which they can change.

To be sure, things that look like changing the past are possible. It’s possible to travel to a parallel universe that is like ours up until a time that is a past time in our universe, and to act at that time so that the future in that universe is different than the future in our universe. So it’s possible to travel to a universe much like ours, kill a baby called ‘Adolf’ and, in so doing, make it the case that in that universe there is no Second World War. That, however, is not changing the past, it is just moving from a universe in which Hitler grew up and started the Second World War, to a universe in which he is killed as a child: our universe remains one in which Hitler was not killed as a baby. With this in mind, we can now construct a new argument against the possibility of time travel.

The Argument from Changing the Past

[P1] It is impossible for some past time, t, to change from being a time at which P to being a time at which not P.

[P2] Therefore there is no possible time traveller who changes some past time, t, from being a time at which P to being a time at which not P.

[P3] If travelling to the past is possible, then there is a possible time traveller ‒ Fred ‒ who travels to a past time, t, and causally interacts with some objects that exist at t.

[P4] If Fred travels to t, and causally interacts with some objects that exist at t, then Fred changes t from being a time at which P to a time at which not P.

Therefore,

[P5] If travelling to the past is possible, then there is a possible time traveller who travels to a past time and changes that time from being one at which P to a time at which not P.

Therefore,

[P6] Travelling to the past is not possible.

Here is a way of thinking about what is going on here. If Fred is a physical object travelling back in time in anything like a world like ours, then he will causally interact with objects at that past time. Even if he tries to be a mere bystander at that past time, he will breathe oxygen, create gravitational changes, refract light, and so on. But if Fred causally interacts with objects at the time to which he travels, then he will change the way things are at the time to which he travels. But it is impossible to change a time. So travelling to the past is not possible.

Does this argument show that time travel to the past is impossible? No. That’s because [P4] is false. Though it appears plausible, it mixes up causally influencing the past with changing the past. Let’s see how.

8.2.2. Influencing versus Changing the Past

[P4] says that if Fred travels to some past time and causally interacts with objects at that time, then Fred changes that time from being one way to being some other way. That looks plausible. When Fred gets out of the time machine and treads on an ant, it seems as though he changes the time from being one in which the ant lived a long and productive life to one in which the ant died and was subsequently eaten by a passing bird.

Fortunately, we can accommodate the thought that Fred is causally efficacious in the past ‒ that Fred can causally affect the time to which he travels by, for instance, treading on ants ‒ without conceding that by doing so, Fred changes the past. Why doesn’t Fred change the past when he treads on the ant? Because there is no first way that the time is, with an untrodden-on ant. There is only one way the time is: which is a time at which the ant is trodden on. It will help to make this clearer if we focus on a block universe model of temporal ontology.

Remember that according to the block universe theorist the entire four-dimensional block of events that did, does, and will occur exists, and that block does not change. Things in the block change, by being one way at one location in the block, and another way at a different location, but the block as a whole is static.

Imagine you are looking down at the whole four-dimensional block (you will need to imagine that you exist outside of time and space, see Figure 18). What do you see occurring at the time to which Fred travels? You see that Fred exits a time machine and treads on an ant. Fred’s being there at that time makes a causal difference to that time. Had Fred not travelled back in time, the ant in question would not have been trodden on. So Fred being located at the time to which he travels is part of what makes that time the way that it is, namely, a way in which an ant is trodden on (and so forth). But Fred doesn’t change that time from being a time with a live ant, to being a time with a dead ant. There is only ever one way that time is: a way with a dead ant.

We’ve used the block universe theory as a way to spell out how to understand influencing the past assuming there is no second time around. But we can do the same for other models of time. Consider presentism. If Fred is about to get into the time machine in the present, and if he does successfully travel back to the relevant time, then it is now true (before he gets into the machine) that Fred was located at that earlier time, and that at that earlier time he did step on the ant. To be sure, the events at that earlier time no longer exist. But they did exist, and when Fred was there, he did step on the ant. Nothing he does now, by getting into the machine, changes what did happen at that earlier time. We leave it as an exercise for the reader to explain how other models of time (such as the growing block and moving spotlight) might understand influencing the past without committing to there being a second time around.

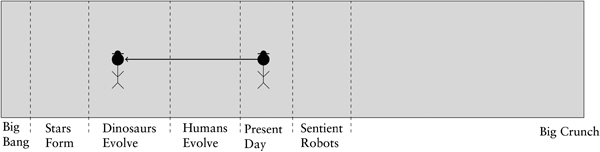

Figure 18 Time Travel in a Block Universe: This figure depicts a block universe with a time traveller, mapping their trajectory, across time.

It’s important to notice that just because there is no second time around, it doesn’t follow that the time traveller does not influence the time to which she travels. Had things gone differently ‒ had the time traveller decided not to travel, for instance ‒ then what happened at the earlier time would have been different: the time traveller would not have been present. So even if it is impossible to change the past, we can make sense of the causal interaction of time travellers with the past.

8.2.3. Hypertime and Changing the Past

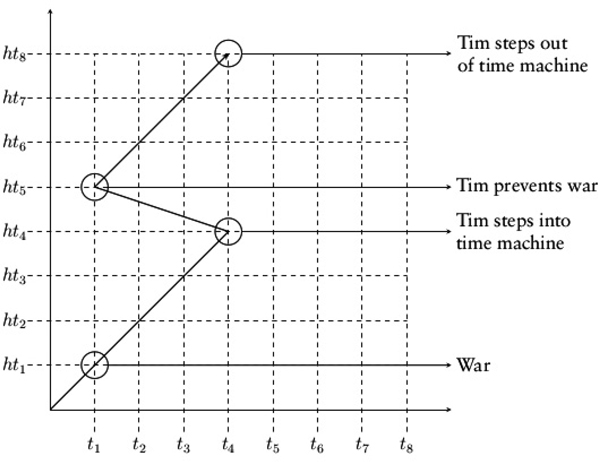

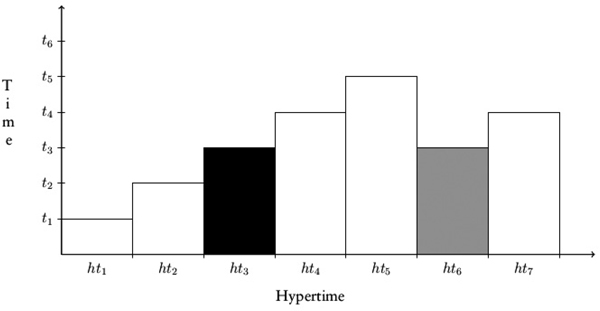

In the previous section we noted that most philosophers think it is impossible to change the past. Unless one posits a second temporal dimension, there is no dimension along which a time can change from being one way to being some other way. If, however, one does posit a second temporal dimension ‒ such as we met in Chapter 2, i.e. hypertime ‒ then perhaps one can make sense of the idea that a time is one way at one hypertime, and another way at some other hypertime. Let us say a little more about how that works, and whether, if it does, it really counts as changing the past. Let’s start by considering a two-dimensional model of changing the past, and let’s assume an eternalist B-theoretic model of temporal ontology. Now, let us say that a time, t, can have one set of properties at one hypertime, and some other set of properties at a different hypertime. To understand how this works we need to introduce not only times (designated by t) but also hypertimes (designed by ht). In a world without time travel, time and hypertime are in sync. A given time t7 will match up to the corresponding hypertime ht7. Once there is time travel, however, times and hypertimes are no longer in sync. Relative to hypertime, a time traveller moves forwards, even if she moves backwards in ordinary time. So, for instance, if Tim steps into a time machine and travels backwards in ordinary time from t4 to t1, he nevertheless travels forwards in hypertime. So, suppose that Tim aims to change the past (t1) to which he travels and then return to the present time (t4) (see Figure 19).

At t1, ht1, we have the ‘original’ version of t1, at which there was, say, a war. At t4, ht4, Tim steps into the time machine and travels back to t1. But the t1 to which he travels is t1, ht5 ‒ t1 as it is, at a different hyper-temporal location. Tim influences t1 (at ht5) preventing the war, and then travels back to t4 at ht8. The t4 to which he returns is different than the t4 from which he travelled (since it is the result of there having been no war). We can make sense both of the change in t1, and the change in t4, by noticing that the changed t1 and t4 occur at different hypertimes.

Figure 19 A Two-Dimensional Time Travel Story: The horizontal axis represents time, the vertical axis represents hypertime. Each point in the 2D space is a time, hypertime pair.

Once we introduce time travel into a model with two-dimensional time we need a complicated two-dimensional diagram, such as Figure 19, to keep track of the various ways times are, at hypertimes. Importantly, not only does the diagram show how to make sense of influencing t1, but it seems to show why this really is a model of changing the past. After all, when Tim returns to t4 (at ht8) everything is different: there was no war, in the past, according to t4, ht8. No one at t4, ht8 remembers a war; there are no records of there having been a war, and so on.

It is controversial whether this really does amount to changing the past, or, as some philosophers have argued, only to avoiding the past. Here is why. What would it take to change the past? One might think that to change the past means to erase the ways things were, in the past, and replace them with some other way things were. Suppose, for instance, one remembers the terrible war that occurred at t1. The aim of changing the past, one might assume, is to erase that event and replace it with some other. That, however, is clearly not what happens in models such as the ones we are discussing. For at t1, ht1 the war occurs. That never changes.

In models such as these, times have hyper-temporal parts: times themselves are ‘extended’ along the hyper-temporal dimension. That means that if a hyper-temporal part of a time is one at which a war occurs, then it is always the case that that hyper-temporal part is one at which a war occurs. To put it another way, the two-dimensional diagram does not change: it is static, just like a block universe is static. If an event occurs at a time/hypertime pair, then it occurs at that pair, and nothing can be done to change that. All that can be done is to create a new ‘version’ of the time, at a different hypertime (t1 at ht5) that is different from that time at some other hyper-temporal location (t1 at ht1). But that is not changing t1 in any sense we care about, since the original t1 at ht1 is still there, as it always was.

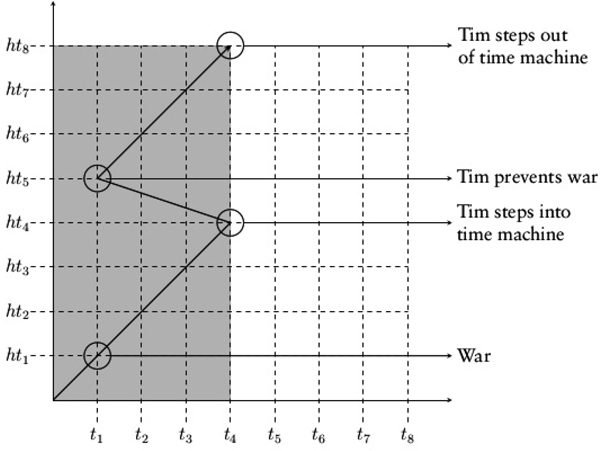

We can make worries such as these a bit more concrete by thinking about what we might mean by ‘the past’ in the context of such models. Consider the two most obvious options. The first option says that what is past, relative to some time t, is the set of time/ hypertime pairs that have as their first member any time that is earlier than, or simultaneous with, t. So relative to t4, in our diagram, the past will be the shaded region in Figure 20. We can easily see why, if this is what we mean by ‘the past’, it will be impossible to change the past. For if an event occurs at some past time/hypertime pair, then that event occurs at that pair: nothing any time traveller does will alter that.

Figure 20 The Past as a Sheet: The entire shaded region corresponds to the two-dimensional past.

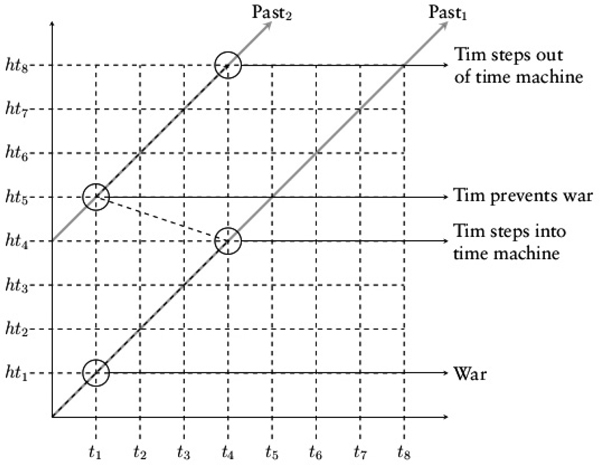

The second option would be to suppose that what is past relative to a time is, in part, determined by which hyper-temporal part of that time we are attending to. Consider t4 at ht4. We could say that the past with respect to that time/hypertime pair is the set of time/hypertime pairs that include only: t0, ht0; t1, h1; t2, ht2; t3, ht3. By contrast, we could say that the past relative to t4 ht8 includes t0, ht4; t1, ht5; t2, ht6; t3, ht8. Then the two different pasts of t4, relative to each hyper-temporal moment, can be depicted as in Figure 21.

Figure 21 The Past as a Trajectory: Each line represents a different two-dimensional past.

On this way of defining the past, then, the past relative to some time/hypertime pair, t, ht, is the set of time/hypertime pairs that includes all pairs in which the time is earlier than t and the hypertime is earlier than ht. But if this is how we think of the past then Tim fails to change the past. Relative to t4, ht4, it was and always will be true that the past is one in which the war occurred. Tim does not change that. And relative to t4, ht8, the past is one in which the war does not occur. But that is, and always will be, true. Tim does not change anything. Nothing goes from having been one way to being some other way. Instead, we simply have two sets of pasts, with Tim travelling between them. He avoids Past 1 by travelling to Past 2, but he changes nothing.

Whether two-dimensional accounts really model changing the past depends, then, on what one thinks it would be to change the past. Defenders of these models point out that in a block universe we are happy to think that objects change by being one way at one time and some other way at some other time: we do not require that the way they were, at the earlier time, has vanished from existence or somehow been ‘overwritten’ by the way things are later. Thus one might argue that when times bifurcate by having hyper-temporal parts, as they do when there is time travel, the objects that exist at those times are the very same objects. If Frank is walking down the street at t1, ht1, then it is the very same Frank walking down the street at t1, ht4. If Tim kills Frank at t1, ht4 then Tim changes the past since he brings it about that Frank ‒ the very same Frank ‒ dies at t1, ht4. It cannot be required that Frank as he is at t1, ht1, is also killed, for that would be contradictory. We won’t adjudicate on this issue any further here.

It’s also worth noting that even if the past really does change on such models, they require that we posit hypertimes. But that is an ontological cost; moreover, there is no evidence for the (actual) existence of hypertimes. So one might complain that positing hypertimes (for any purpose) is really just ad hoc. We have no reason to posit such things other than that we want to accommodate changing the past: but that’s not a reason to posit a whole additional temporal dimension! This is worth bearing in mind since, as we will see, more recently somewhat different models of changing the past within a dynamic temporal ontology have been offered. What both sets of models share, however, is an appeal to hypertimes. If one thinks that positing hypertimes is unmotivated, then regardless of whether one thinks that these models do model changing the past, one will think that, at best, changing the past is logically possible (but not actual), and, at worst, one will think that there are no worlds with hypertimes, and hence no world where in fact the past is changed. We will return to this issue shortly. For now, we will end our discussion of the logical possibility of time travel here. In what follows we move on to consider whether time travel is metaphysically possible.

8.3. Is Time Travel Metaphysically Possible?

So far we have asked whether there is anything about the nature of time travel itself that is contradictory, and in virtue of which time travel is logically impossible. We failed to find any such contradiction. That, however, does not show that time travel is metaphysically possible. For it could still be that time travel is inconsistent with our best metaphysical theories of the world. Perhaps, for instance, presentism is true, and true of metaphysical necessity. Then if time travel is inconsistent with presentism, time travel is metaphysically impossible. It is this, and possibilities like it, that we shall now consider.

8.3.1. Presentism and Time Travel

Recall that on an eternalist temporal model, past, present and future objects exist, as do past, present and future times. According to eternalism, just as spatial locations other than the one that you or I are located at exist, so too temporal locations other than those at which you or I are located exist. On the face of it, then, it seems plausible to suppose that, in principle, just as you and I can travel to other spatial locations, so too you and I can travel to other temporal locations.

Suppose, however, that presentism is true. Presentism is the view that only present concrete entities exist. So it is easy to see why one might be sceptical that presentism is compatible with time travel. After all, it seems that there are no past concrete locations to which to travel. This objection is known as the no destination argument.

The No Destination Argument

[P1] A time traveller can only travel to a location, L, if L exists.

[P2] If presentism is true, past locations do not exist.

Therefore,

[C] If presentism is true, no time traveller can travel to any past location.

If the no destination argument is sound, and if presentism is true and metaphysically necessary, then time travel is metaphysically impossible.

The argument, however, faces a problem. Suppose we replace ‘past’ with ‘future’ throughout the argument. Then the argument shows that we cannot travel into the future either, since according to presentism future locations do not exist. But presentists think we are travelling into the future as we speak. So either this argument is really an argument against presentism itself ‒ since it shows that time cannot flow the way the presentist says it does ‒ or the argument is unsound. In either case, it doesn’t show that time travel is incompatible with presentism. What should the presentist say about travel into the future? How do we manage to travel from this moment to the next moment, a moment that is, at present, a future and hence non-existent moment? The presentist will say that we can do this because by the time we get to that future moment, it is no longer future but present, and hence exists. Consider a spatial analogy. Suppose some spatial location ‒ call it non-existent land ‒ does not presently exist, but someone is selling tickets to travel to it. Suppose, though, that the tickets specify that the journey will take ten years. At the end of ten years, we are assured, non-existent land will exist because the spacetime that will constitute non-existent land is being created as we speak. The presentist should insist that travelling to a future time is like travelling to non-existent land. The future time does not exist now, but it will exist, at the point where we reach it. But if the presentist can say that about a future time, then she can also say it about a past time. To be sure, no past time now exists. But all that matters is that said time used to exist; that the past time was there, when the time traveller arrived.

So it seems that the presentist has a good response to these kinds of objections. There is no reason to think that presentism is incompatible with time travel, and thus no reason to think that even if presentism is metaphysically necessary, time travel is metaphysically impossible.

8.3.2. Moving the Present to Change the Past

We have already considered time travel in a presentist world. It is worth noting that while it is generally agreed that we can tell a coherent time travel story that is consistent with presentism, not everyone is so sure that this ought really to count as time travel. After all, what really happens? The traveller is located in the now – the only moment at which objects can exist. By getting into a time machine now, the time traveller makes it the case that some past-tensed statement is true. She makes it true, for instance, that she existed at some past time. The objects that existed at that time, however, including the time traveller herself, no longer exist. So if the time traveller gets into the time machine and flips the switch, she brings it about that she ceases to exist. To be sure, she also brings it about that she did exist, at some earlier time, but in so doing she also brings it about that she does not exist. That is because the time to which the traveller travels is objectively past, and hence the objects that existed at that time no longer exist. Time marches ever onwards regardless of the actions of the time traveller. If t20 is the objectively present moment, then the next objectively present moment will be t21, regardless of the fact that the time traveller travels to t5.

Recent models of time travel have sought to avoid this outcome by holding that the time traveller effectively takes the present moment with her when she travels. So, suppose we are considering Frederika, who travels from t5 to t3. In order to understand how this works we need to invoke hypertimes. As before, hypertime always unfolds chronologically. And, again, in the absence of time travel, hypertime and time are always in sync. Time travel, however, consists in moving the objectively present moment; in effect, this is to re-wind time. We can suppose that Frederika was not, originally, i.e. the first time around, at t3. But by travelling there she re-winds time so that t3 is the objectively present moment, and she exists at t3. In hypertime then, the order of times is as follows: t1, t2, t3, t4, t5, t3, t4, t5. Hypertime always unfolds chronologically, ht1, ht2, ht3, ht4, ht5, ht6, ht7, so the order of times in hypertime is as follows: ht1, t1; ht2, t2; ht3, t3; ht4, t4; ht5, t5; ht6, t3; ht7, t4; ht8, t5.

Since there are multiple ways of modelling temporal dynamism there are multiple versions of this model of changing the past. We shall focus on just two: the presentist version and the growing block version. On the presentist version of the model only the present moment exists. By travelling to past times, the time traveller takes the present moment with her: no other times exist, other than the time to which she travels. So, at ht7, only t3 exists. On the growing block version of the model, by contrast, when the time traveller travels back in time she effectively erases all of the block from the location to which she travels, up until the time at which she departed. So if the traveller leaves in 2016, and arrives in 1970, she deletes the block between 1970 and 2016. Then a new block regrows from the new 1970. But the regrown block will be different from the original block, since the time traveller will causally affect the way things progress. Hence, she will have changed the past.

What both models share is the idea that because the traveller moves the objective present around, she can have a ‘do-over’ of time: there really is a second time around that is different from the first time around. There is no contradiction involved since the way things were, the first time around, has been erased from existence by the movement of the objective present. What this means is that different facts about the past will be true at different hypertimes. If Frederika travels back in time and goes to a wedding that she avoided the first time around, then there will be a hypertime ht3, at which, in the past, Frederika did not attend the wedding, and a hypertime ht6, at which, in the present, she does attend the wedding, and a hypertime ht7, at which, in the past, she did attend the wedding.

Does this model accommodate changing the past? It’s worth noticing that there are two ways we can think about hypertime in this model. First, we could think that hypertime is eternalist: all hyper-temporal events that did, do, or will exist, do exist. If we think of hypertime this way, then it is not clear that this model is really any better than the standard two-dimensional model we previously considered. Suppose that the growing block model is right, and we consider Frederika and her wedding-attending behaviour. Suppose that at t3, the first time around, Frederika fails to attend the wedding, and that is why, at t5, she travels back to t3 in order to attend the wedding. So the first time around at t3 Frederika is absent from the wedding, and the second time around at t3 Frederika is present at the wedding. That means that at some hypertime (namely ht3) Frederika is absent at the wedding at t3, and at some other hypertime, namely ht6, Frederika is present at the wedding at t3. If the hyper-temporal dimension is eternalist ‒ all hypertimes are equally real ‒ then we can represent this as in Figure 22. For our purposes what matters is that the absence of Frederika at the wedding at t3 still exists at hypertime ht3. To be sure, it no longer exists in time, at ht6: that slice of reality has been deleted. But it is still true, at ht6, that at an earlier moment in hypertime, t3 (a time without the wedding attendance) exists. The slice has been erased from time, but not hypertime. The same is true if presentism is true of ordinary time, but eternalism is true of hypertime. Then although at ht3 the only time that exists, t1, is one in which there is wedding attendance, there is some earlier hypertime, ht1, in which the only time that exists, t1, is a time at which there is no wedding attendance. In general, if we pair any dynamic theory of ordinary time with a non-dynamic, eternalist model of hypertime, we get a model that shares many of the features of the two-dimensional models we have already considered. If the two-dimensional model we previously considered cannot accommodate genuinely changing the past, then it is hard to see how these models do any better.

The only way to avoid this consequence would be to hold that hypertime is presentist. Then the only hypertime that exists, let us suppose, is ht6, and hence there is no record at all of Frederika’s failure to attend the wedding at ht3, t3. For the sum totality of reality is represented by just the sub-portion of the diagram in Figure 22, which is the block that exists as of ht6, since no other hypertimes exist. Of course, it will always be true that, at some earlier hypertime, it was true that, in the past, the wedding was not attended. That can never be changed: the past-time hyper-temporal facts are there to stay. But there is no record of these in ontology. They are, effectively, erased. If anything is to count as changing the past this will be it. We leave it to the reader to consider whether the resulting picture of time and of reality is any good.

Figure 22 Dynamic Time, Hypertime and Time Travel: Hypertime is eternalist, and ordinary time is modelled by the growing block. At ht3, t3 Frederika fails to attend the wedding. At ht6, t3 Frederika attends the wedding. The block that exists at ht3 and ht6 are different. At ht7, t4 it is true that Frederika did attend the wedding at t3.

8.4. Is Time Travel Improbable?

We turn now to consider whether time travel is improbable, despite being logically, metaphysically and nomologically possible. Why might we think time travel is improbable? Well, if time travel is probable, then lots of people are likely to travel in time. But if lots of people are travelling in time, we should expect quite a few of them to be trying to change the past in various ways, including, for instance, trying to kill their young grandfathers. All these attempts to change the past, and to kill young grandfather, will fail. So if time travellers are repeatedly engaging in these kinds of behaviours, we should see a whole range of failed attempts to do things like kill grandfathers. Indeed, for any past event, E, that a time traveller repeatedly attempts to change, there will be a series of failed repeated attempts to change E. So if enough time travellers are engaged in enough attempts to change the past, we expect to see long strings of coincidences in which individuals repeatedly fail to achieve their intended goals. We will, for instance, see a great many gun jammings, or sudden changes of heart, or cases of mistaken identity as each time traveller’s murderous attempts are foiled. We do not, however, see these long strings of coincidences. Since there would be such strings of coincidences if time travel were probable, and since we don’t see these coincidences, it follows that time travel is improbable.

The Argument from Improbability

[P1] If time travel is probable, then for some past events, E1 … En, there will be multiple attempts to change each of E1 … En.

[P2] Each attempt to change each of E1 … En will fail because changing the past is impossible.

[P3] As each attempt to change each of E1 … En fails, there will be a long string of coincidences.

Therefore,

[P4] If time travel is probable, we will see a long series of such coincidences.

[P5] We do not see a long series of such coincidences.

Therefore,

[C] Time travel is not probable.

In response to the argument outlined above, one might begin by disputing the claim that if time travel is probable, lots of time travellers will try to change the past. After all, perhaps once time travel technology is developed, potential time travellers will be much more metaphysically sophisticated than we are, and they will all just agree that they will not succeed in changing the past, so they won’t even try. If we think it is not likely that time travellers will try to change the past, then the above argument clearly fails to show that time travel is improbable. But suppose we think that it is likely that time travellers will attempt to change the past. Then should we conclude that time travel is improbable?

Probably not. Certainly, we have not, as yet, seen the long strings of coincidences that the argument appeals to: cases of mysterious failures to murder youthful grandpas. So if we think it likely that time travellers will try to change the past, there is something we can conclude: namely that time travellers have not travelled to anywhere near here (temporally speaking). Time travellers have not travelled to our local past, or to this time. For if we think it likely that time travellers will try to change the past, then, given that we do not see long strings of coincidences, we know that time travellers are not trying to change the past around here. But that does not establish that time travel is improbable. After all, there are very many locations to which time travellers can travel besides this one. So maybe they just haven’t bothered to visit us yet. Or maybe they can’t, because of some other constraint that they are under (perhaps it requires too much energy to get here).

The argument from improbability asks us to infer that because there are no strings of coincidences in our local past, there are no strings of coincidences anywhere, and therefore that it is improbable that there are time travellers anywhere. That inference may well be false. Consider the following analogy. Imagine Parramatta Road (a main road in Sydney) in the 1920s. Were someone to roll a whole bunch of tomatoes down Parramatta Road in 1920, it would be unlikely, and coincidental, if every tomato was hit, and squashed, by a car. That is because there was very little traffic in 1920, so most tomatoes should escape unharmed. Following the same line of reasoning used in the argument from improbability, though, we should infer from this that if we roll a bunch of tomatoes down Parramatta Road today, it will be coincidental if every one of them is squashed. That, however, is clearly a mistake, since there is a lot of traffic on Parramatta Road today. Indeed, it would be coincidental if any tomatoes, rolled down the road, failed to be squashed.

The point, then, is this. Tomato squashings in 1920 were improbable. But what is improbable depends on local conditions: in this case the absence of cars on the road. What is true for tomato squashings is true for so-called strings of coincidences. We cannot infer that there will not, in the future, be strings of coincidences, just because there were no such strings of coincidences in the past. After all, if future time travellers bent on changing the past begin to travel back in time to, say, ten years in our future, then in ten years we will begin to see strings of coincidences: except, of course, they will not seem coincidental any more. If lots of time travellers try to kill their young grandfathers, then in ten years’ time we will expect to see a lot of failed attempts on the lives of grandfathers. Failed attempts such as these will become probable. So just as we cannot infer from the fact that tomato squashings were rare in 1920 to the fact that they are rare now, and then to the fact that there will be little traffic on the roads now, so too we cannot infer from the fact that there are few failed grandfather-killing attempts in the local past, to the fact that there will be few failed grandfather killings in the future, to the fact that there will be no time travellers located in the future trying to kill their young grandfathers.

So we have found no reason to think that time travel is improbable. At best we have reason to think that there are no time travellers in our local past, hell bent on changing the past in various ways.

8.5. Time Travel, Free Will and Deliberation

So far we’ve considered whether time travel is logically, metaphysically or nomologically impossible, and whether it is improbable. But time travel might be possible, and indeed probable, and still raise difficult metaphysical issues. In particular, one might think that if it is indeed impossible to change the past, then various interesting issues are raised regarding how time travellers ought to deliberate about what to do in the past.

8.5.1. Are Time Travellers Free?

According to the analysis of ‘can’ discussed in section 8.2, a person can do something if doing that thing is compatible with their capacities. But perhaps that is not the right account of ‘can’. A better account might be this: a person can do something, and hence is free to do that thing, only if, were they to try, they would, or might, succeed. Sara has, in fact, never tried to fly. What makes it true that she cannot fly, and that she is not free to fly, is that were she to try, it is not the case that she would, or might, succeed. How do we evaluate whether or not a person would, or might, succeed in doing something that they have not, in fact, ever attempted to do? We have already met the answer to this question in chapter 6, when we appealed to counterfactual conditionals. Recall that the claim that were Sara to do X, Y would happen (even though Sara doesn’t, in fact, do X), is a counterfactual conditional. We noted, in chapter 6, that a common way to evaluate counterfactuals involves imagining what happens at worlds where the antecedent of the counterfactual is true. So, for instance, consider the counterfactual: if Yufei were to drive at 200 miles per hour, she would crash. This is true if, amongst the worlds in which Yufei does drive at 200 miles per hour, there is no world in which she fails to crash, which is closer to the actual world than any world in which Yufei drives at that speed and does crash.

So let’s return to our worry about freedom. Suppose that a person is able to do something if, were they to attempt to do it, they would, or might, succeed. Then we could say that a person might succeed in doing something only if there is some nomologically possible world in which they succeed in doing that thing. So, consider whether Sara can eat toast for breakfast. She can, on this view, since even if in fact she has never attempted to do so, there are lots of nomologically possible worlds in which she attempts to eat toast and succeeds. By contrast, consider the question of whether Sara can fly. Clearly, Sara can’t, because there is no nomologically possible world in which she tries to fly and succeeds. It might be thought that the same broad story applies to killing young grandfather. For there is no nomologically possible world in which any of us attempts to kill young grandfather and succeeds. (We will succeed in very distant worlds in which babies can be resurrected, but that is irrelevant for the purposes of determining whether or not any of us can kill young grandfather.)

If the broad approach to ‘can’ discussed above is right, then it shows that although time travel is possible, the freedom of time travellers to act in the past is constrained in ways that it is not constrained in the present. After all, there are nomologically possible worlds in which, for each of us, if we attempt to kill our ageing grandfathers then we succeed. So it is now true, for each of us, that we can kill our ageing grandfathers. Thus we are now free to do things that we are not free to do in the past.

But is it correct to say that we can kill ageing grandfather, but cannot kill young grandfather? Let us think a bit more closely about how we go about assessing counterfactuals. Think about the case of breakfast. We want to know whether there is a nomologically possible world in which, when Sara attempts to eat toast, she succeeds. Suppose, though, that we asked the following question: is there any nomologically possible world in which, given that Sara in fact eats cornflakes, she eats toast? No. In any world (and thus in the nomologically possible ones), if Sara eats cornflakes at a particular time, she doesn’t eat toast at that time.

To make this point clearer, consider what we might call the class of permanent bachelors. This is a class of people who, by definition, remain bachelors their entire lives. Suppose Jeff is a member of that class. We can ask whether Jeff could have married. The answer is surely yes: there are nomologically possible worlds in which Jeff decides to marry, and succeeds. So he can marry. Indeed, for each person in the class of permanent bachelors, surely each of them can marry: there is no powerful anti-marriage demon preventing each of them from marrying. But of course, if Jeff marries, then he is no longer in the class of permanent bachelors. What it is to be a member of that class is to fail to marry. But suppose we ask whether, given that Jeff is a permanent bachelor, he can marry. Well there is no nomologically possible world in which Jeff is a permanent bachelor and he succeeds in marrying. Indeed there is no possible world in which Jeff is a permanent bachelor and he marries. Yet we would hardly conclude, from this, that Jeff is not free to marry. We would conclude that when we assess whether Jeff can marry, we ought to determine whether or not there is a nomologically possible world in which he marries, not whether there is a nomologically possible world in which he is both a permanent bachelor and marries.

The mistake we make when assessing whether Jeff can marry, if we hold fixed that he is a permanent bachelor, is the same mistake we make when we assess counterfactuals about killing young grandfather. Or so goes the thought. Here is why. What it is to be a permanent bachelor is to fail to marry. So when we ask about Jeff’s capacity to marry, we shouldn’t hold fixed that he is a permanent bachelor, for then we hold fixed that Jeff fails. Likewise, when we ask whether time traveller Fred can kill young grandfather, we are illicitly holding fixed the relations between Fred and the young man he attempts to kill, and therefore holding fixed that he fails. Suppose we simply ask: can Fred kill that young man? Then the answer is yes. For there is a nomologically possible world in which Fred kills that young man: that will be a world in which a man just like that one exists, but is not Fred’s grandfather. So although there is no nomologically possible world in which Fred kills young grandfather, we should not conclude from this that Fred lacks freedom because he can’t kill young grandfather. For we get the same result if instead we ask whether Jeff, the permanent bachelor, can marry. In each case, though, when we assess the correct counterfactual, we find that Jeff can marry, and that Fred can kill young grandfather.

8.5.2. Deliberating About the Past

We have already seen that philosophers distinguish changing the past from causally affecting the past, and that most hold that the former is impossible, and the latter possible. Suppose this is right. If time travellers can causally affect, but not change, the past, it seems reasonable to ask: what sorts of things ought time travellers try to do? Given that Tim’s grandfather is alive in 2017, not only do we know that Tim will not kill his grandfather in 1980, but Tim is also in a position to know that he will not kill his grandfather in 1980. Here’s where things get interesting. Plausibly, someone can only deliberate about whether to do X, if that individual does not know whether or not X. For instance, one cannot deliberate about whether to turn blue when one knows one won’t turn blue. So suppose one knows exactly what happened on some day in the past, including knowing that one’s future self time travels to that day, puts on a duck suit, and marches in the ‘free the ducks’ parade. Then one cannot deliberate about whether one will travel back in time to that day and put on the duck suit, any more than one can deliberate about whether to turn blue. That’s because one knows what one will do, and knowing what one will do precludes one from deliberating about what to do.

It is, however, rare that we know everything about some past time. So that leaves plenty of room for potential time travellers to deliberate about what to do in the past. Some things, no doubt, will be ruled out as deliberation worthy. In so far as Sara is certain that Hitler grew to adulthood, she cannot deliberate about whether to travel back in time to kill him in his youth, since she knows that she does not succeed in doing any such thing.

Of course, we have greater and lesser amounts of evidence about the past. Sometimes evidence is weak. In cases where evidence is weak, or where the stakes are high, a traveller might rationally deliberate about acting in the past so as to bring about some desirable consequence. For instance, suppose a traveller has weak evidence that 10,000 people died of famine at some past time. Then she might decide to travel back to give them crop advice, reasoning that the weak evidence she has that they died of famine may be misleading, and that by travelling back in time and offering advice she might save 10,000 lives. After all, perhaps it is now true that 10,000 people did not die of famine, though they almost did, and perhaps that is true because the traveller narrowly managed to prevent the famine.

Indeed, some have wondered whether it is reasonable for time travellers to manufacture evidence about the past in precisely these sorts of cases. Suppose that rather than there being weak evidence that there was a famine, there is really a fair amount of historical evidence. Then either the famine occurred, in which case there is no point in the traveller travelling back in time to try and prevent it, or the famine did not occur, perhaps because the traveller prevented it, and the evidence in the historical records is misleading. In so far as the traveller is motivated to try to make it the case that the 10,000 people did not die from famine, it seems that she has reason to try and fabricate historical evidence of a famine.

To see why, suppose the traveller is considering whether to travel back in time to try and prevent the famine. She has some reason not to do this, given her evidence that the famine occurred. But suppose she travels back to times after when the famine would have occurred, if it did, and instead tells a range of famous historians a story about a terrible famine that killed 10,000 people. If the traveller does this, then she has an excellent explanation for why there is evidence of a famine: namely her time travelling self is responsible for the evidence. But then the traveller has reason to think that the evidence of the famine having occurred is misleading. Since she will then not be sure that the famine did happen, it will be rational for her to decide to travel back in time to attempt to prevent the famine from happening.

So it seems that the traveller ought to first travel back in time and plant evidence that there was a famine, then travel further back and make sure the famine does not occur. But, you might think, it cannot be reasonable to manipulate evidence in this way: after all, either the famine happened or it didn’t; either the traveller prevented it, or she failed to, and no amount of manipulating historical records will change that.