Prostitution as a form of exchange (Simmel, 1971) or a location where cultural values and market logics intersect (Zelizer, 1994) has long interested social scientists, but male sex work remains underresearched (Bimbi, 2007; Pruitt, 2005; Weitzer, 2009). In general, male sex workers (MSWs) are difficult to conceptualize in current economic, social, and gender theories of prostitution because all participants are the same gender (Bernstein, 2005, 2007; Edlund & Korn, 2002; Giusta, Di Tommaso, & Strom, 2009; Marlowe, 1997).1 Qualitative research on male sex workers informs theories of sexuality, sexual behaviors, and sex work (Parsons, Bimbi, & Halkitis, 2001; Bimbi & Parsons, 2005; Uy et al., 2004); however, many quantitative questions whose answers could complement the qualitative approach remain unanswered. For example, we know little about the population size or geographic distribution of MSWs. Quantitatively analyzing the market could increase our understanding of ways that commerce, sexuality, and masculinity intersect.2

While there is a relative wealth of research about male sex workers who work on the streets, little is known about male escorts who appear to occupy the highest position in the hierarchy of male prostitution (Cameron, Collins, & Thew, 1999; Koken et al., 2005; Luckenbill, 1986; Parsons, Koken, & Bimbi 2007; Pruitt, 2005; Uy et al., 2004). Due to technological progress, such as the Internet, and the increasing social acceptance of homosexuality (Loftus, 2001; Scott, 2003), most existing work is now out of date.3 Recent qualitative scholarship finds that the demographic and social characteristics of male escorts and their reasons for entering commercial sex work described in earlier postwar research does not apply today (Calhoun & Weaver, 1996; Joffe & Dockrell, 1995; Parsons et al., 2001; Pruitt, 2005; Uy et al., 2004). Researchers also note male-on-male sex workers’unique social and epidemiological position because they serve numerous social groups: gay-identified men, heterosexually identified men, and their own noncommercial sexual partners (Cohan et al., 2004). Male sex workers thus interact with groups of men who are unlikely to interact with each other, potentially acting as a social and sexual conduit between various groups (Parker, 2006).

One unique aspect of the study of gay male-on-male sex work is that all of the participants are male. In contrast to male-female prostitution, one cannot easily assign sexual positions or behaviors to participants based on gender; this necessitates a discussion of the social value of sexual behaviors practiced and advertised by escorts in the market.4 This chapter analyzes how and if men who have sex with men reify and critique hegemonic masculinity in the values of sexual behaviors;5 this is especially interesting because gay men are often considered counter-hegemonic (Connell, 1987, 1995).6 Moreover, scholars note that ethnic sexual stereotypes give rise to unique values of practices among men of particular ethnicities and cultures. I therefore explore how ethnic and cultural subjectivities further shape the constructions of masculinity in these communities (Collins, 1999, 2000; Han, 2006; Reid-Pharr, 2001).

This study breaks new ground in the study of male sex work by taking an explicitly quantitative approach to the subject. The relationship between escort prices, personal characteristics, and advertised sexual behaviors provides an interesting window through which to view this relatively underinvestigated social activity in the U.S. (Bimbi, 2007; Weitzer, 2009). The conceptual framework begins by considering how this type of empirical analysis can shed light on social theories of sexuality and masculinity (Dowsett, 1993). Principles of economic theory motivate the empirical approach, but results are interpreted in light of social theories of male sexuality. As the male escort market in the United States does not use intermediaries who could control the prices and earnings of male escorts, how male escorts price their services is understood to be conditional on their personal characteristics and advertised sexual behaviors. Values attached to these characteristics and behaviors lie at the confluence of social value and market forces.

This study renders visible some interesting aspects of male-on-male escort sex work in the U.S., such as where male escorts are predominantly located; advertising in cities with high and low gay density; and the market value of personal physical characteristics, such as ethnicity, height, and weight, and of advertised sexual activities. It explores whether male sex workers’ clients value hegemonically masculine behaviors and appearance in a way that can be reconciled with hegemonic masculinity (Connell, 1987, 1995; Connell &Messerschmidt, 2005), and what, if any, are the effects of intersections between personal physical characteristics and advertised sexual behaviors in these markets. It tests the hypothesis of intersectionality theory, which posits that men of particular cultural and ethnic subjectivities are rewarded for downplaying or emphasizing certain sexual behaviors (Collins, 1999, 2000).

Online Markets for Commercial Male-on-Male Escort Sex Work in the U.S.

Popular media suggest that MSWs are a sizable portion of the broader U.S. sex worker population (Pompeo, 2009; Steele & Kennedy, 2006).7 Unlike their female counterparts, male sex workers usually work independently, as there is virtually no pimping or male brothels in the U.S. male sex trade (Logan & Shah, 2009; Pruitt, 2005; Weitzer, 2005, 2009).8 The independent, owner-operator feature of these markets allows for greater mobility within the hierarchy of the male sex worker market. In these hierarchies, male escorts are arguably the most esteemed, as they do not work the streets, they take clients by appointment, and they usually are better paid than their counterparts on the street (Luckenbill, 1986). While street sex workers are paid at a piece rate, male escorts are contract employees with greater control over the terms of their work and the services they provide.9

Male escorts used to congregate in “escort bars” and place advertisements in gay-related newspapers to solicit clients, but reports show that the male escort market now takes place online (Friedman, 2003; Pompeo, 2009; Steele & Kennedy, 2006).10 The online market provides a straightforward operating procedure—escorts pay a monthly fee to post their advertisements, which include pictures, physical descriptions, their rate for services (quoted by the hour), as well as contact information such as telephone numbers and email addresses. Escorts have complete control over the type and amount of information conveyed in their advertisements. Through websites, clients contact escorts directly and arrange for appointments at the escort’s home (known as an “incall”) or at the client’s residence or a hotel (an “outcall”).

Social Science Theories of Male Sex Work

Research on commercial sex work traditionally concentrates on women and neglects the heterogeneous social structures that give rise to diverse forms of male sex work (Bernstein, 2007; West, 1993). Surveys of male prostitution (Aggleton, 1999; Itiel, 1998; Kaye, 2001; Pompeo, 2009; Steele & Kennedy, 2006; West, 1993) render visible geographic and cultural distinctions in practices and forms of male sex work, making it difficult to generalize the phenomena over space or time. These difficulties have hindered research in this field. Theories of sexuality pay particular attention to sexual minorities and marginalized sexualities because they are central to understanding majority and minority sexualities and sexual subjectivities (Epstein, 2006; Sedgwick, 1990; Stein, 1989; Weinberg & Williams, 1974). Including male sex workers confounds the usual theoretical tools of power and gender, allowing explorations of dynamics within genders in a novel way (Marlowe, 1997).

Research on political economies among sexual minorities deals largely with the commoditization of gay desire (Cantu, 2002; D’Emilio, 1997). As commoditization is a market force with supply, demand, quantities, and prices, I investigate how men in male sex work markets construct subjectivities that are influenced by social factors. This in turn can tell us about values men place on themselves and other men for commercial and perhaps noncommercial sexual liaisons. Researchers have looked at these types of values qualitatively and quantitatively between genders (Almeling, 2007; Arunachalam & Shah, 2008; Koken, Bimbi, & Parsons, 2009), but little quantitative work looks at differences within genders.

Today, as in the past, significant numbers of male escorts and clients do not identify as homosexual (Bimbi, 2007; Chauncey, 1994; Dorais, 2005). Allen (1980) describes studies of MSWs that find less than 10 percent identify as homosexual. Since Humphries’s (1970) controversial work, social scientists have noted that men partaking in same-sex sexual behavior are unlikely to be found in surveys unless they choose to publicly reveal their sexual behaviors and desires (Black et al., 2000; Black, Sanders, & Taylor, 2007; Cameron et al., 2009). The world of male sex work is one of the few places where men who adopt homosexual identities and those who refuse them are in intimate contact with one another; this offers the opportunity to address interesting questions about male sexual identity and homosexual desire. For example, what roles and behaviors must escorts conform to in order to realize the largest economic gains from sex work? The value of these roles can inform an analysis of the construction of masculinity at the crossroads of heterosexual and homosexual subjectivities because men participating in these markets, both clients and escorts, adopt disparate sexual subjectivities.

Economic and Demographic Approaches

While it can be difficult to identify all sexual minorities in any data source (Berg & Lien, 2006; Black et al., 2000, 2002; Cameron et al., 2009), researchers can now identify same-sex couples. Using population trends, scholars note that the geographic distribution of male same-sex couples is different from that of the general U.S. population (Black et al., 2000, 2002; Black et al., 2007). City amenities and the ability to congregate and socialize within a dense urban population appear related to gay locality patterns (Black et al., 2002).11 Whatever the reason for these locality differences, this research poses interesting questions about the demography and geography of male sex work, as we know very little about the population size, demographic characteristics, and geographic distribution of male sex workers in the U.S.

Early studies of male sex work focused on cities with large gay populations (McNamara, 1994), but more recent qualitative research reveals that a significant portion of male escorts’ clientele identifies heterosexually.12 Indeed, the “breastplate of righteousness” that Humphries (1970) saw in heterosexually identified men who took part in homosexual behavior has recently resurfaced in the public lexicon (Frankel, 2007; MacDonald, 2007). In the market for male sex work, such behavior is common. Male escorts note that a significant percentage of their clientele is heterosexually identified and many are married. Because these men are obscured from the most common analysis of sexual minorities, how their presence in the market influences market function and composition remains unexamined.

Simple economic models of locality, such as Hotelling’s (1929), suggest that escorts should locate close to their client base. Given that heterosexually identified men may have much to lose if their same-sex sexual behavior is exposed, it is expected that male escorts might be more likely to locate in places where there are fewer opportunities for these men to meet other men, such as neighborhoods and communities identified as predominantly heterosexual. Self-identified heterosexual men are unlikely to frequent gay bars, coffeehouses, or community groups where they might encounter gay men for socialization or sex. Male escort locations should thus differ from those of general gay-identified populations. Conversely, researchers note that gay communities do not attach the same level of stigma to sex work as heterosexuals do (Koken et al., 2009; Sadownick, 1996). Thus, if gay communities are seen as safe havens for sex workers, or if few customers are heterosexually identified, it would be expected that male sex workers’ geographic distribution would closely mirror that of the general gay population’s.

Sociological Approaches

Hegemonic Masculinity

Hegemonic masculinity is defined as “the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of legitimacy of patriarchy” (Connell, 1995, p. 77). Hegemonic masculinity is about relations between and within genders.13 Hegemonically masculine practices ensure the dominant position of men over women, and of particular men over other men. These practices can take a number of forms; research usually stresses social traits such as drive, ambition, self-reliance, and aggressiveness, which legitimate the power of men over women. Within genders, there is the privileging or dominance of certain masculinities and the marginalization or subordination of others (Bird, 1996; Reeser, 2010; Schrock & Schwalbe, 2009). For example, gay masculinities are subordinated and marginalized so that patriarchy can be reproduced through heterosexuality. Connell (1995) describes how hegemonic masculinity is never influenced by non-hegemonic elements: elements of non-heterosexuality are seen as contradictions or weakness (Demetriou, 2001), thus diminishing the perceived power of these subjectivities.

Scholars note the limits of this conceptual binary between hegemonic and non-hegemonic masculinity (Anderson, 2002; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Demetriou, 2001; Donaldson, 1993; Dowsett, 1993; Reeser, 2010). Demetriou (2001) and Reeser (2010), among others, suggest that rather than viewing it as binary, hegemonic masculinity should be viewed as a hybrid made up of practices and elements of heterosexual and homosexual masculinities, giving hegemonic masculinity the ability to change over time to meet historical circumstances with a different set of practices. In this conception, the practices of gay men, who are non-hegemonic, not only reinforce the patriarchal goal of hegemonic masculinity, but they help define the hegemonic ideal itself.14 Demetriou (2001), for example, notes the recent construction of the “metrosexual” as one example of gay masculinity influencing the construction of the hegemonic ideal.

While a binary approach views gay men in relation to the hegemonic ideal, a hybrid approach opens the possibility of analyzing how gay men define, subordinate, and marginalize masculinities among themselves. This within-subgroup construction might influence how hegemonic masculinity itself is defined. Donaldson (1993) and Connell (1992) note that gay men reify hegemonic norms; indeed, modern gay practices celebrate and exemplify hegemonic ideals such as bodybuilding and physical strength. This reification of masculine norms can create a situation where some gay masculinities are themselves subordinate to others. That is, among gay men themselves, there may be further refinement of the gay masculine norm along hegemonic lines. Donaldson (1993) raises the intriguing point that “it is not ‘gayness’ that is attractive to homosexual men, but ‘maleness.’ A man is lusted after not because he is homosexual but because he’s a man. How counter-hegemonic can this be?” (p. 649).

Scholars of masculinity have asserted that gay men critique hegemonic ideals through their counter-hegemony (Connell, 1992; Reeser, 2010), but it also could be the case that gay men overtly reify hegemonic ideals sexually. To the extent that this occurs, gay masculinities may be aligned with the hegemonic masculinity that marginalizes them. The question is the degree to which homosexual men are complicit in hegemonic masculine norms. In Demetriou’s (2001 language, to what degree do gay masculinities contain significant elements of hegemonic masculinities that legitimate patriarchy and may, in turn, influence hegemonic masculinity itself? In an explicitly sexual arena, hege-monic masculinity would extend to physical appearance (e.g., muscularity, body size, body hair, and height) and sexual behaviors (e.g., sexual dominance, sexual aggressiveness, and penetrative sexual position). To the extent that homosexual men conform to and reify hegemonic masculine norms, it is expected that the value of masculine traits and practices should have a direct effect on a given escort’s desirability and value. While such “manhood acts” usually elicit deference from other men and reinforce hegemonic masculinity (Bird, 1996; Schrock & Schwalbe, 2009), in an explicitly homosexual arena they may also elicit sexual desire and objectification.

The function of male sex work in gay communities may heighten such effects. In a market for sex work, clients are explicitly seeking sexual contact. Clients may choose escorts unlike the men they interact with socially but whom they do desire sexually. This may increase the value of certain masculine characteristics insofar as the hegemonic masculine archetype may be a driving force in purely sexual desire (Cameron et al., 1999; Green, 2008a; Pruitt, 2005; Weinberg & Williams 1974).15 In this market, is men’s lust consistent with hegemonic norms? Sexual desire for the hegemonic ideal could influence how hegemonic masculinity itself is constructed and reinforced among gay men. If this is the case, there may be limits to the binary view of hegemonic masculinity.

This type of hybrid hegemonic masculinity could have additional implications for gay male body image and gay men’s use of the body in constructing masculinity. Sadownick (1996) sees the gay liberation movement as a time when gay men began, en masse, to idealize hypermasculinity, muscles, and a hirsute body, turning on its head the “flight from masculinity” that Hacker (1957) observed in earlier generations of gay men. The physical ideal is typified by a muscular physique and other markers of hegemonic masculinity, such as height, body hair, whiteness, youth, and middle-class socioeconomic status (Atkins, 1998; Green, 2008b). This turn of events has molded the gay body into a political representation of masculinity. This partly subverts norms that question the compatibility of masculinity and homosexuality, but it also reinforces a quasi-hegemonic masculine ideal (Atkins, 1998; Connell, 1992). Compared with lesbians and heterosexuals, gay men show stronger tendencies to prefer particular body types, and this can lead to poor psychological and health outcomes for gay men who do not conform to gay standards of beauty (Atkins, 1998; Beren et al., 1996; Carpenter, 2003; Green 2008b; Herzog et al., 1991). In fact, attempts by some gay subcultures to subvert these beauty standards have been critiqued as being agents themselves of hegemonically masculine agendas (Hennen, 2005).

In many ways, rejection of large men and thin men can be seen as the rejection (subjugation) of feminizing features. For example, excess weight in a man visually minimizes the relative size of male genitals and produces larger (and, importantly, nonmuscular) male breasts; thin men may appear slight, waifish, and physically weak. These appearances emphasize feminizing traits that are actively discouraged in mainstream gay culture (Atkins, 1998; Hennen, 2005). In the market for male sex work, we expect clients to prize physical characteristics that mark hegemonic masculinity, such as muscular physiques, body hair, and height. We also expect feminizing features, such as excess weight and thinness, to be penalized.

The theory of hegemonic masculinity and the closely related literature on the body in gay communities suggest that clients of male sex workers are likely to prize masculine personas and body type. There are several reasons for this. First, numerous scholars assert that gay men’s relationships with effeminate behavior are complex—while celebrated in many aspects of gay culture (e.g., camp, drag shows, and diva worship), effeminate behavior is particularly stigmatized in sexual relationships and as an object of lust (Clarkson, 2006; Nardi, 2000; Ward, 2000). Second, some scholars note how the gay community has commoditized the “authentic” masculinity of self-identified heterosexual men who engage in sex with men (Ward, 2008). This has given rise to the distinction between masculine and effeminate gay men in gay communities (Clarkson, 2006; Connell, 1992; Pascoe, 2007). Construction of dual masculinities among gay men, and distinctions between the two, are used to legitimate the power of masculine gay men over effeminate gay men, a reproduction of patriarchy (Clarkson, 2006). We thus expect that men who are interacting primarily for sexual purposes likely place a premium on masculine practices (e.g., penetrative sexual position [topping], aggressive sexual behavior, and muscular physique) and penalize feminine practices (e.g., receptive sexual position [bottoming], submissiveness, large body size, and thinness) to the degree that they conform to hegemonic masculinity and to the construction of masculine gay identity among gay men.16

Just as the theory of hegemonic masculinity has been critiqued for not considering how gay men can conform to and inform hegemonic masculinity, there is also a burgeoning literature that looks at ethnic variation in social values among gay men (Green, 2008a; Han, 2006; Nagel, 2000; Robinson, 2007). As intersectionality theory suggests, the intersection of these social categories is neither cumulative nor additive but independent (Collins, 1999, 2000; Reeser, 2010). The intersection of hegemonic masculinity with ethnic sexual stereotypes can create multiple forms of sexual objectification for particular groups of gay men. For example, the value of a top (the penetrative partner) is not uniform across all tops, and the value of a white top is not simply the addition of the value of whiteness and “topness” but an independent effect for men in that particular category, who in this instance embody the highest position in the racial and sexual behavior hierarchies among gay men. Markets for sex may reify these sexual stereotypes (what Cameron and colleagues [1999] call “ethnico-sexual stereotypes”) in explicitly monetary terms.

Baldwin (1985) notes that the American ideal of sexuality is rooted in the American ideal of masculinity, which he argues necessitates an inherently ethnic dimension. Historically, white men were to protect white women from black sexuality, and this supposed threat legitimated white men’s social control of white women (and whites social control over blacks). For homosexual white men, black men’s sexuality may become an object of desire because they are perceived to be sexually dominant and unrestrained—although still under the social control of whites due to their ethnicity—turning the hegemonic ideal on its head (Baldwin, 1985; Reeser, 2010). Robinson (2008), McBride (2005), Reid-Pharr (2001), Green (2008a), and others note how racial stereotypes interact with notions of masculinity to produce a desire for hypermasculine black men, particularly among white gay men.

The stereotype of the sexually dominant black man, rather than being an agent of fear, can lead to a celebration of his hypersexual behavior, appearance, and conduct. In this theory, the general level of social interaction between black and white gay men is relatively low and occurs chiefly over sex. Black men who demonstrate hypermasculine and sexually aggressive behavior are offered entry into white gay spaces, but this entry is limited to sexual liaisons. McBride (2005), for example, notes the limited range in which black men interact with whites in gay pornography, where the vast majority of black performers are tops and adopt an antisocial persona. Men who defy ethnic sexual stereotypes could face markedly lower values and become, in this particular instance, counter-hegemonic. Robinson (2008) finds that white gay men largely ignore and devalue black men who do not conform to the stereotype of the hypermasculine black male, suggesting that the penalties for nonconformity may be particularly harsh.

The reverse is true for Asians, whose passivity and docility are celebrated. Robinson (2007, 2008), Phua and Kaufman (2003), and Han (2006) describe the persistent stereotype that Asian men should be passive, docile bottoms. As with black men, this ethnic sexual stereotype allows the larger gay community to limit Asian men’s socially acceptable sexual expressions. In this case, the counter-hegemonic activity is for Asian men to appear sexually dominant or aggressive. These authors also note that Hispanics are celebrated as passionate, virile lovers who are usually sexually dominant, although not exclusively so, making it difficult to derive quantitative predictions for this group.

Given these racial sexual stereotypes, it is necessary to consider how the values of particular sexual behaviors differ by ethnicity. Phua and Kaufman find that dating “preferences for minorities often are tinted with stereotypical images: Asians as exotic, docile, loyal partners; Hispanics as passionate, fiery lovers; and Blacks as ‘well-endowed,’ forbidden partners” (2003, p. 992). If the market for male sex work mirrors the gay community at large, we expect the analysis will show that black men who advertise themselves as tops and Asian men who advertise as bottoms command higher prices, thus reflecting the value of conforming to ethnic sexual stereotypes.

Exploring the Gay Male Sex Market

In order to overcome a number of problems of sample selection, this study uses data collected from the universe of men advertising online on the largest, most comprehensive, and most geographically diverse website for male escort work in the U.S. (identified herein as site X).17 This online source has several advantages. First, it allows me to collect information on escort attributes, prices, and information unhampered by the selection problems that would be encountered in a field survey of escorts.18 Second, I can identify escorts’ home locations, which allows for accurate geographic counts. Third, the escort characteristics I use are entered by the escorts themselves from drop-down menus. This is of particular advantage for exploring the features escorts use to control their pricing models (e.g., body type or hair color). Fourth, website X is free for viewing by anyone connected to the Internet. This ensures that the information provided is for a large general client base and not manipulated to please paying members of a website for a more specific market.

In order to demonstrate that the data source provides sufficient coverage of the online escort market, table 5.1 compares escorts on site X with the two most prominent competitors from a random sample of smaller cities. The appeal of site X is that escort locality is identifiable, whereas this information is not consistently available on any of the other two comparison sites. Data would be compromised if the comparison sites were included in the study, as the same escorts could be counted individually across the sites inflating the figures. Table 5.1 shows that site X has a considerably larger escort base identifiable by locality than its competitors. The last column of table 5.1 shows the number of escorts on site X that could also be identified on Rentboy. The comparison data reveal the many of the escorts who advertise on the comparison websites also advertise on site X, whereas not all escorts advertising on site X were found on the comparison sites.

Escorts list their age, height, weight, race, hair color, eye color, body type, and body-hair type. Advertisements give clients contact information, the preferred mode of contact (i.e., phone or email), escorts’ availability to travel nationally and internationally, and prices for incall and outcall services. Escorts can write about their services and quality in an advertisement’s text.19 One additional advantage of these data is that the escorts’ claims about their physical characteristics can be confirmed by viewing the pictures posted in the advertisements.20 The analysis is based on outcall prices, but results do not change when using incall prices.

TABLE 5.1

Comparison of Male Escort Websites

| |

|

Number of Escorts |

|

| CITY |

SITE X |

RENTBOY |

MALE ESCORT REVIEW |

SITE X / RENTBOY |

| Albany, NY |

5 |

0 |

3 |

N/A |

| Austin, TX |

26 |

3 |

15 |

2 / 3 |

| Buffalo, NY |

5 |

0 |

0 |

N/A |

| Charlotte, NC |

19 |

3 |

4 |

2 / 3 |

| Columbus, OH |

30 |

3 |

13 |

3 / 3 |

| Denver, CO |

41 |

5 |

19 |

5 / 5 |

| Detroit, MI |

73 |

10 |

14 |

9 / 10 |

| Indianapolis, IN |

19 |

0 |

5 |

N/A |

| Kansas City, MO |

9 |

1 |

7 |

0 / 1 |

| Minneapolis, MN |

33 |

2 |

15 |

2 / 2 |

| Nashville, TN |

14 |

1 |

8 |

1 / 1 |

| Oklahoma City, OK |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 / 1 |

| Portland, OR |

15 |

1 |

12 |

1 / 1 |

| Sacramento, CA |

17 |

7 |

5 |

5 / 7 |

| St. Louis, MO |

18 |

3 |

6 |

2 / 3 |

| Seattle, WA |

33 |

14 |

23 |

11 / 14 |

| Rochester, NY |

4 |

0 |

0 |

N/A |

| Tampa, FL |

47 |

15 |

22 |

11 / 15 |

| TOTAL |

411 |

69 |

171 |

55 / 69 |

Table 5.2 shows summary statistics for the escorts in the data. On average, escorts charge more than US$200 an hour for an outcall, consistent with media estimates of escort services (Pompeo, 2009; Steele & Kennedy, 2006). As one would expect, escorts are relatively young and fit; on average, they are 28 years old, 5 feet 10 inches tall, and 165 pounds (approximately 155cm and 75kg). According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the average man aged 20 to 74 years in the U.S. is 5 feet 9.5 inches and 190 pounds (approximately 154cm and 86kg). Escorts are ethnically diverse; 54 percent are white, 22 percent are black, 14 percent are Hispanic, 8 percent are multiracial, and 1 percent are Asian.

Looking at physical traits, escorts are likely to have black (37 percent) or brown (46 percent) hair; less than 15 percent are blond). More than half of all escorts have brown eyes (55 percent), although significant fractions have blue (18 percent) and hazel (14 percent) eyes. Nearly half of all escorts are smooth (49 percent), 17 percent shave their body hair, but more than a third are hairy or moderately hairy (34 percent). Very few escorts are overweight (1 percent), and relatively few are thin (8 percent); the majority of escorts claim to have athletic (48 percent) or muscular (30 percent) builds. Looking at sexual behaviors, 16 percent of escorts are tops, 6 percent are bottoms, and 21 percent list themselves as versatile.21 In addition, 19 percent of escorts advertise that they exclusively practice safer sex. Overall, summary statistics for men in the data are similar to descriptive statistics noted by Cameron and colleagues (1999) for male escorts in British newspapers in the 1990s and Pruitt’s (2005) more recent sample of male escorts who advertise on the Internet.

TABLE 5.2

Summary Statistics for the Escort Sample

| VARIABLES |

OBS |

MEAN |

SD |

| Price |

1,476 |

216.88 |

64.46 |

| Log of Price |

1,476 |

5.34 |

.29 |

| Weight |

1,932 |

167.11 |

24.54 |

| Height |

1,932 |

70.43 |

2.69 |

| BMI |

1,932 |

23.64 |

2.89 |

| Age |

1,932 |

28.20 |

6.93 |

| Asian |

1,932 |

.01 |

.12 |

| Black |

1,932 |

.22 |

.41 |

| Hispanic |

1,932 |

.14 |

.35 |

| Multiracial |

1,932 |

.08 |

.28 |

| Other |

1,932 |

.01 |

.10 |

| White |

1,932 |

.54 |

.50 |

| PHYSICAL TRAITS |

|

|

|

| Hair Color |

|

|

|

Black Black |

1,932 |

.37 |

.48 |

Blond Blond |

1,932 |

.13 |

.34 |

Brown Brown |

1,932 |

.46 |

.50 |

Gray Gray |

1,932 |

.02 |

.13 |

Auburn/Red Auburn/Red |

1,932 |

.01 |

.11 |

Other Other |

1,932 |

.01 |

.10 |

| Eye Color |

|

|

|

Black Black |

1,932 |

.02 |

.14 |

Blue Blue |

1,932 |

.18 |

.39 |

Brown Brown |

1,932 |

.55 |

.50 |

Green Green |

1,932 |

.11 |

.31 |

Hazel Hazel |

1,932 |

.14 |

.35 |

| Body Hair |

|

|

|

Hairy Hairy |

1,932 |

.04 |

.20 |

Moderately Hairy Moderately Hairy |

1,932 |

.30 |

.46 |

Shaved Shaved |

1,932 |

.17 |

.38 |

Smooth Smooth |

1,932 |

.49 |

.50 |

| Body Build |

|

|

|

Athletic/Swimmer’s Build Athletic/Swimmer’s Build |

1,932 |

.48 |

.50 |

Average Average |

1,932 |

.13 |

.34 |

A Few Extra Pounds A Few Extra Pounds |

1,932 |

.01 |

.08 |

Muscular Muscular |

1,932 |

.30 |

.46 |

Thin/Lean Thin/Lean |

1,932 |

.08 |

.27 |

| BEHAVIORS |

|

|

|

Top Top |

1,932 |

.16 |

.37 |

Bottom Bottom |

1,932 |

.06 |

.24 |

Versatile Versatile |

1,932 |

.21 |

.40 |

Safe Safe |

1,932 |

.19 |

.39 |

Note: Price is the outcall price posted by an escort in his advertisement.

Empirical Strategy

Previous quantitative work analyzing male escorts has not examined prices of male escort services (Cameron et al., 1999; Pruitt, 2005). The data in this study have been analyzed on male escort services’ prices in a hedonic regression; a technique developed by Court (1939), Griliches (1961), and Rosen (1974). The basic technique regresses the price of a particular good or service on its characteristics (such as ethnicity, hair color, body build, etc). This type of regression is widely used in economics, and it is particularly useful for goods that are inherently unique or bundled. This regression analysis is able to tell us how much prices increase or decrease, on average, for services based on the personal characteristics and advertised behaviors of the escorts. Estimated coefficients from hedonic regressions are commonly interpreted as implicit prices because they reflect the change in price one could expect, on average, for a change in that particular characteristic. It is common to refer to positive coefficients as a premium and negative coefficients as a penalty.23

Empirical Results

Geographic distribution of male sex workers

Table 5.3 shows the geographic distribution of male escorts advertising on site X. Figures are based on the actual number of escorts by the home locality provided in their advertisements. To my knowledge, this is the first large-scale quantitative evidence on the geographic location of male escorts in the U.S. Size of the escort population varies considerably; there are more than 300 escorts in only one city, New York, which has long been depicted in the media as the largest male escort market (Pompeo, 2009). Atlanta, Los Angeles, Miami, and San Francisco each have more than 100 escorts, but most cities have considerably fewer.

There is a striking trend in terms of location patterns: the number of gay escorts closely follows the size of a metropolitan statistical area (MSA), not gay locality patterns. For example, Detroit is the 11th largest MSA in the U.S. and its gay concentration is 42nd, but there are 51 percent more escorts in Detroit than in Seattle, a city with the fifth highest gay concentration index (GCI). Chicago and St. Louis display a similar pattern. Indeed, correlation of the number of escorts with MSA population is quite strong (r = .92), but it is much weaker with the GCI (r = .39). Furthermore, the correlation of per capita escorts with the GCI (r = .69) is weaker than the correlation of escorts with MSA.

TABLE 5.3

Geographical Distribution of Escorts in Random Selection of Cities

|

METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREA |

GAY CONCENTRATION |

|

| CITY |

RANK |

POPULATION |

RANK |

INDEX |

NUMBER OF ESCORTS |

| New York, NY |

1 |

18,815,988 |

13 |

1.49 |

309 |

| Los Angeles, CA |

2 |

12,875,587 |

6 |

2.11 |

126 |

| Chicago, IL |

3 |

9,524,673 |

18 |

1.31 |

93 |

| Miami, FL |

7 |

5,413,212 |

14 |

1.46 |

119 |

| Washington, DC |

8 |

5,306,565 |

2 |

2.68 |

99 |

| Atlanta, GA |

9 |

5,278,904 |

7 |

1.96 |

108 |

| Boston, MA |

10 |

4,482,857 |

9 |

1.67 |

53 |

| Detroit, MI |

11 |

4,467,592 |

42 |

.6 |

50 |

| San Francisco, CA |

12 |

4,203,898 |

1 |

4.95 |

124 |

| Seattle, WA |

15 |

3,309,347 |

5 |

2.21 |

33 |

| Minneapolis, MN |

16 |

3,208,212 |

10 |

1.61 |

33 |

| St. Louis, MO |

18 |

2,808,611 |

37 |

.69 |

18 |

| Tampa, FL |

19 |

2,723,949 |

24 |

1.05 |

47 |

| Denver, CO |

21 |

2,464,866 |

12 |

1.53 |

41 |

| Portland, OR |

23 |

2,175,113 |

15 |

1.45 |

15 |

| Sacramento, CA |

26 |

2,091,120 |

8 |

1.71 |

17 |

| Kansas City, MO |

29 |

1,985,429 |

25 |

1.04 |

9 |

| Columbus, OH |

32 |

1,754,337 |

27 |

.99 |

30 |

| Indianapolis, IN |

33 |

1,695,037 |

19 |

1.12 |

19 |

| Charlotte, NC |

35 |

1,651,568 |

45 |

0.49 |

19 |

| Austin, TX |

37 |

1,598,161 |

3 |

2.44 |

26 |

| Nashville, TN |

39 |

1,521,437 |

32 |

.85 |

14 |

| Oklahoma City, OK |

44 |

1,192,989 |

34 |

.83 |

3 |

| Buffalo, NY |

46 |

1,128,183 |

49 |

.35 |

5 |

| Rochester, NY |

50 |

1,030,495 |

29 |

.89 |

4 |

| Albany, NY |

57 |

853,358 |

31 |

.85 |

5 |

| Correlation of Number of Escorts with GCI |

|

|

.39 |

| Correlation of Per Capita Escorts with GCI |

|

|

.69 |

| Correlation of Number of Escorts with MSA Population |

|

|

.92 |

Note: The OMB defines these population groups as clusters of adjacent counties. Gay concentration is the fraction of the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) identified as same-sex male partners in the 1990 census divided by the national average (for further details, see Black et al., 2007). MSA population counts from the Census Bureau as of July 1, 2007. Cities with MSA rank greater than 12 were randomly selected from the 50 cities listed in Black and colleagues (2007).24

This result is consistent with the claim that the market for male sex work is national in scope and not driven exclusively by gay-identified participants. If escort services were primarily demanded by self-identified gay men, we would expect the geographic distribution of male escorts to mirror the geographic distribution of self-identified gay men. That is, male escorts would locate in places with a higher concentration of potential customers (Hotelling, 1929). Results in table 5.3 suggest that male escorts tend to concentrate in cities with substantial populations, not just cities with substantial gay populations. This result holds even when considering midsized and smaller cities—it is not driven by cities that have large populations and large gay populations, such as Los Angeles. Overall, the evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that male escorts serve a market that includes a substantial number of heterosexually identified men.

Physical characteristics and male escort prices

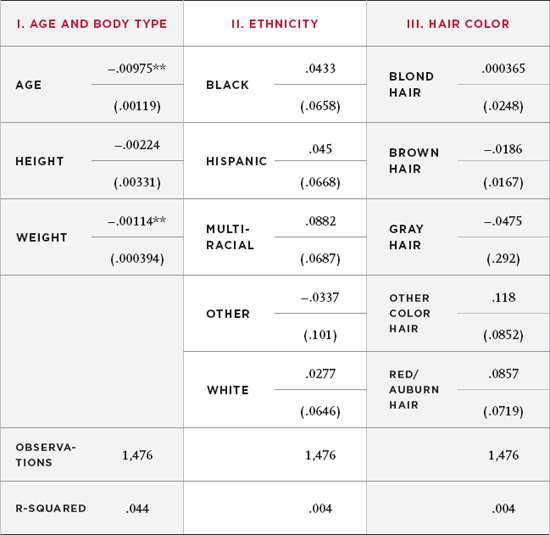

Table 5.4 shows estimates of the value of physical characteristics on the pricing of male escort services from hedonic regressions of escort prices on physical characteristics. Given that clients in commercial sex markets generally tend to be older men (Friedman, 2003), we would expect clients to prize youth and beauty, consistent with female sex work (Bernstein, 2007). The theory of hegemonic masculinity and related literature on the gay body, however, predict that hegemonically masculine physical traits would be prized in the market. In describing the results, I emphasize the percentage differences, but to increase the exposition, I also give the dollar value of the differentials based on an average price of US$200 per session. It is important to emphasize that these differentials are cumulative. For example, a 10 percent ($20) price differential per session could lead to earnings differences in excess of $5,000 per year.25

TABLE 5.4

The Implicit Prices of Physical Characteristics in the Male Escort Market on Site X

Note: Robust standard errors are listed under coefficients in parentheses. Each category is a separate regression in which the log of escort prices is the dependent variable. Each regression includes controls for city location and an intercept. For model II, the omitted ethnicity category is Asian. For model III, the omitted hair color is black. For model IV, the omitted eye color is black. For model V, the omitted body build is athletic/swimmer’s build. For model VI, the omitted body hair is hairy.

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed tests).

These data indicate that there is a penalty for age, with each additional year of age costing an escort 1 percent ($2) of his market price. There also is a penalty for weight, with each additional 10 pounds resulting in over a 1.5 percent ($3) market price decrease.26 Body build, which is closely related to weight, also appears to be an important market variable. Men with average body types experience a price penalty that exceeds 15 percent ($30), while men who have excess weight experience a price penalty of more than 30 percent ($60).27 There is also a price penalty for thinness, although it is not as large as the penalty for those who are average or overweight, being on the order of 5 percent ($10, p < .1). This is consistent with work that finds a large social penalty for additional weight among gay men (Carpenter, 2003), theoretical work that describes codes of body image in gay communities (Atkins, 1998), and literature on the body that suggests significant penalties for weight among gay men, as both excess weight and thinness have feminizing features. Men with a muscular build, however, enjoy a price premium of around 4 percent ($8, p < .1). Indeed, only men who have muscular builds enjoy a price premium relative to the reference category “athletic/swimmer’s build.” Because muscularity is a physical signal of maleness and dominance and can be considered a proxy for strength and virility, the premium attached to muscularity in this market is consistent with hegemonic masculinity.

Surprisingly, ethnicity does not seem to play a role in escort prices. No stated ethnicity commands higher prices in the market than any other. While some escorts of color claim they are paid less than their white counterparts (Pompeo, 2009), these data do not support that claim. The same holds for hair color, eye color, body hair, and height. Interestingly, body hair and height, both of which indicate masculine traits, do not come with premiums in this market. In general, these results challenge theories that stipulate there is a hegemonic ideal: no ethnicity/hair color/eye color/body hair combination appears to be more valuable than any other. Other than weight and body build, it appears that most personal characteristics are not very important variables in the male escort market.

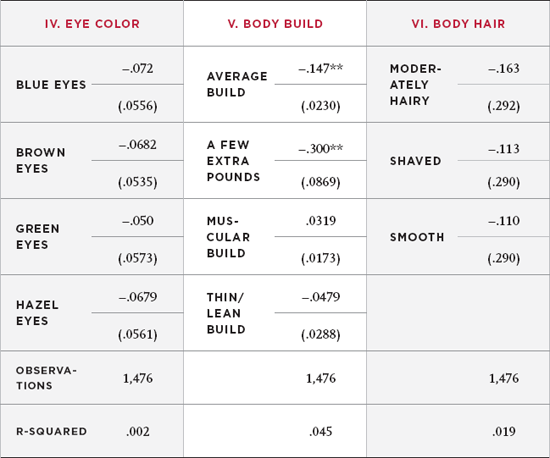

Sexual behaviors and male escort prices

Table 5.5 shows estimates of the value of advertised sexual behaviors on male escort prices. An important implication of hegemonic masculinity is the idea that dominant sexual behaviors would be rewarded in the male escort market. Consistent with hegemonic masculinity, the premium to being a top is large, over 9 percent ($18), and the penalty for being a bottom is substantial—in some specifications (column V), it is nearly as large as the premium for being a top, on the order of –9 percent ($18). The price differential for men who are tops versus men who are bottoms—the top/bottom differential—is substantial, ranging from 14.1 percent ($28, column I) to 17.6 percent ($35, column V).28

The substantial premium to tops and penalty to bottoms is interesting for a number of reasons. Premiums for these sexual behaviors are inconsistent with the economic concept of compensating differentials, where riskier occupations (in this market, sexual behaviors) are compensated with higher wages. According to research in public health, the relative risk of contracting HIV for receptive versus penetrative anal sex is 7.69 (Varghese et al., 2002). This implies that the correlations we observe are in spite of the fact that receptive sexual activity carries greater disease risk than does the penetrative sex act. Compensating differentials would predict that bottom escorts should be compensated for taking on this increase in disease risk, but I find exactly the opposite. In studies of female sex work, the compensating differential is substantial (Gertler, Shah, & Bertozzi, 2005). The empirical estimates also find a positive correlation between advertised safety and escort prices, greater than 5 percent ($10). As further evidence against an idea of compensating differentials for male sex work, I find no premiums for particular types of safe sex—men who advertise as “safe tops” or “safe bottoms” do not enjoy a distinct premium, although transmission probabilities would suggest that they should.29

These results can be interpreted sociologically, however, as the premium attached to masculine behavior in gay communities. The premium for tops is consistent with literature that notes that gay men prize traditionally masculine behaviors and sexual roles, and the penetrative partner in sexual acts is canonically considered more masculine. The fact that men who act in the dominant sexual position charge higher prices for services is consistent with the social acceptance of quasi-heteronormativity within groups of men who have sex with men. As described earlier, gay communities prize behavior that can be described as hegemonically masculine, and this extends to sexual acts themselves (Clarkson, 2006).

TABLE 5.5

The Implicit Prices of Sexual Behaviors in the Male Escort Market on Site X

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Dependent variable is the log of an escort’s price in all regressions. Each regression includes controls for age, city location, and an intercept.

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed tests).

Alternative explanations for the top premium bear mentioning. One possibility is that the premium may derive from the biology of being a top. If “topping” requires ejaculation and “bottoming” does not, this could limit the number of clients that tops could see in a given period of time and drive the premium upward; essentially there could be a “scarcity premium” for top services. A search of escort advertisements, however, reveals that top escorts who mention bottoming also mention that they charge a significant premium for bottoming services. Similarly, a detailed analysis of client reviews and online forums does not show that clients demand ejaculation more from top escorts than from bottoms. I take this as evidence of the social penalty of bottoming and the premium of topping. While biology could certainly play a role, the social position of tops appears to be the dominant force behind the top premium.30

The intersection of ethnicity and sexual behaviors

As described earlier, the intersection of ethnicity and sexual behaviors could shed light on the connection between hegemonic masculinity and ethnic sexual stereotypes. In particular, black men are expected to be dominant sexually and Asians are expected to be passive. I investigate these intersections by looking at interactions across ethnicities and sexual behaviors. Table 5.6 shows estimates of the value of advertised sexual behaviors for men by ethnicity, where each entry shows the implicit price of the interaction of that ethnicity and sexual behavior (e.g., the premium or penalty to being an Asian top or a versatile white).

The results are striking. Black, Hispanic, and white men each receive a substantial premium for being tops, but the largest premium is for black men (nearly 12 percent, $24). The premium for Hispanics is greater than 9 percent ($18, p < .1), while the premium for whites is less than 7 percent ($14). There is no statistically significant top premium for Asian escorts. The penalty for being a bottom also varies by ethnicity: white bottoms face a penalty of nearly 7 percent ($14, p < .1), while black bottoms face a penalty of nearly 30 percent ($60), the largest penalty seen in any of the results in table 5.6. There is no bottom penalty for Asians or Hispanics. The top/bottom price differential also varies by ethnicity. While the differential for whites and Hispanics is close to the overall top/bottom differential—13.2 percent ($26) and 12.3 percent ($25), respectively; the estimates of table 5.6 put the differential between 14.1 percent and 17.6 percent—the differential for blacks is more than twice the differential for any other racial group, 36.5 percent ($73).31 These results are consistent with the intersectionality theory, in which black men who conform to stereotypes of hypermasculinity and sexual dominance are highly sought after, and those who do not conform are severely penalized. These types of stereotypes appear within the male escort market, and they influence premiums and penalties for sexual behaviors. Predictions for Asians, however, are not borne out in the data—I found neither a top premium nor a bottom penalty for Asian escorts.

TABLE 5.6

The Implicit Prices of Ethnicity and Sexual Behavior Interactions in the Male Escort Market on Site X

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Each column is a separate regression where the log of the price is the dependent variable. Each entry is the coefficient of the interaction of the row and column. For example, the “Black Top” coefficient is the coefficient of the black*top interaction term in the regression. All regressions include controls for ethnicity, city, sexual behaviors, other personal characteristics, and an intercept.

* p < .05; ** p < .01 (two-tailed tests).

Limitations and Future Research

While this study makes use of novel data to test theories of male sex work, several limitations to the present analysis should be noted. First, I analyzed only the largest website for escort advertisements in the U.S., and the results might not hold for competitors’ sites. For example, if certain types of escorts are more likely to congregate at different websites, they would not be captured in my data, limiting my ability to describe the market in general. Second, information in the advertisements is posted by the escorts and therefore constitutes a self-report. While I exploited independent data to confirm the precision of the price measure, I cannot say with certainty that there are no omitted confounders in the data. Third, the dataset may be missing variables that could influence the price of escort services, such as endowment, an escort’s education level, or expertise in specific sexual conduct.

These limitations should inform future research. For example, future studies should analyze competing websites with a similar methodology to confirm or challenge results presented here. Similarly, detailed analysis of client-operated websites, which review escort services, could act as an independent check on the veracity of the information posted in escort advertisements. Future research should develop panel data on male escorts that would allow one to track escorts over time to see how and if their behaviors, identities, advertisements, and personas change, which would add an important dimension to this literature.

Discussion and Conclusions

This chapter has addressed important questions pertaining to male sex work. These questions relate to basic facts about male escorts, their geographic distribution, and the relationship between escort characteristics, sexual behaviors, and prices. Using a unique quantitative data source of male sex workers, the study uncovered a number of facts that should stimulate further research into male sex work and related areas of gender, sexuality, masculinity, ethnicity, and crime. In general, the results suggest that male sex work is markedly different from its female counterpart. It also shows how concepts from ethnographic, qualitative, and theoretical work in social science can be subjected to quantitative empirical approaches, including statistical tests of hypotheses.

The data show that escorts are present in cities with low and high gay concentrations; this result supports work that suggests a significant portion of the male escort clientele is not gay-identified. Personal characteristics, except for those pertaining to body build, are largely not related to male escorts’ prices. Muscular men enjoy a premium in the market, while overweight and thin men face a penalty, which is consistent with hegemonic masculinity and the literature on the body and sexuality. Conformity to hegemonic masculine physical norms is well rewarded in the market.

The premium to being a top is substantial, as is the penalty for being a bottom, again consistent with the theory of hegemonic masculinity. When intersecting these behaviors with ethnicity, it was found that black men are at the extremes—they have the largest premiums for top behavior and the largest penalties for bottom behavior. This is consistent with intersectionality theory in that gay communities prize black men who conform to racialized stereotypes of sexual behavior and penalize those who do not. While the sexually dominant black male is feared in heterosexual communities, he is rewarded handsomely in gay communities.

Given the quantitative results, the ways in which desire intersects with ethnic stereotypes should receive significant attention in future masculinity studies. Theoretically, these results should renew attention on the complex construction of masculinities among gay men, in which counter-hegemonic groups adopt and reiterate hegemonic masculine norms among themselves, explicitly reinforcing hegemonic norms. In particular, further work at the nexus of the construction of masculinity among gay men, hegemonic masculinity, and ethnic inequality would be a fruitful area of research.

Further research on ethnicity, sexuality, and commerce is needed to address issues unexplored here. For instance, due to data limitations, class dimensions inherent in male sex work have remained unexplored. An important question for intersectionality theory in light of the results presented here is how ethnicity and sexual behavior intersect with class masculinities to yield premiums and penalties in this market. Furthermore, causal estimates of male escort behavior on prices, which would be key for policy discussions such as the feasibility of sexual behavior change among male sex workers to minimize disease risk (Connell, 2002) also have not been explored. Implications for men involved in this market—socially, sexually, and health-wise—should certainly be investigated further at greater depth.

Research on male sex work needs to move at an accelerated pace. As the discussion in this chapter shows, there is much to be gained from an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to the subject. Future developments along this line would enhance and extend our understanding of sexuality and gender in general and male sex work in particular, shedding light on important issues in social research and public policy.

References

Aggleton, P. (Ed.). (1999). Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV/AIDS. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Allen, D. M. (1980). Young male prostitutes: A psychosocial study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9, 399-426.

Almeling, R. (2007). Selling genes, selling gender: Egg agencies, sperm banks, and the medical market in genetic material. American Sociological Review, 72, 319-340.

Anderson, E. (2002). Openly gay athletes: Contesting hegemonic masculinity in a homophobic environment. Gender and Society, 16, 860-877.

Arunachalam, R., & Shah, M. (2008). Prostitutes and brides? American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 98, 516-522.

Atkins, D. (Ed.). (1998). Looking queer: Body image and identity in lesbian, gay, and transgender communities. New York: Routledge.

Bajari, P., & Benkard, C. L. (2005). Demand estimation with heterogeneous consumers and unobserved product characteristics: A hedonic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 1239-1276.

Baldwin, J. (1985). The price of the ticket: Collected nonfiction 1948-1985. New York: St. Martin’s.

Bartik, T. J. (1987). The estimation of demand parameters in hedonic price models. Journal of Political Economy, 95, 81-88.

Bates, T. R. (1975). Gramsci and the theory of hegemony. Journal of the History of Ideas, 36, 351-366.

Beren, S. E., Hayden, H. A., Wilfley, D. E., & Grilo, C. M. (1996). The influence of sexual orientation on body dissatisfaction in adult men and women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 135-141.

Berg, N., & Lien, D. (2006). Same-sex sexual behavior: U.S. frequency estimates from survey data with simultaneous misreporting and non-response. Applied Economics, 38, 759-769.

Bernstein, E. (2005). Desire, demand, and the commerce of sex. In E. Bernstein & L. Schaffner (Eds.), Regulating sex: The politics of intimacy and identity (pp. 101-128). New York: Routledge.

Bernstein, E. (2007). Temporarily yours: Sexual commerce in post-industrial culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bimbi, D. S. (2007). Male prostitution: Pathology, paradigms and progress in research. Journal of Homosexuality, 53, 7-35.

Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2005). Barebacking among internet based male sex workers. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 9, 89-110.

Bird, S. R. (1996). Welcome to the men’s club: Homosociality and the maintenance of hegemonic masculinity. Gender and Society, 10, 120-132.

Black, D., Gates, G., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2000). Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic sources. Demography, 37, 139-154.

Black, D., Gates, G., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2002). Why do gay men live in San Francisco? Journal of Urban Economics, 51, 54-76.

Black, D., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2007). The economics of lesbian and gay families. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 53-70.

Boyer, D. (1989). Male prostitution and homosexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 17, 151-184.

Brown, J. N., & Rosen, H. S. (1982). On the estimation of structural hedonic price models. Econometrica, 50, 765-768.

Calhoun, T. C., & Weaver, G. (1996). Rational decision-making among male street prostitutes. Deviant Behavior, 17, 209-227.

Cameron, S., Collins, A., Drinkwater, S., Hickson,, F., Reid, D., Roberts, J. et al. (2009). Surveys and data sources on gay men’s lifestyles and socio-sexual behavior: Some key concerns and issues. Sexuality & Culture, 13, 135-151.

Cameron, S., Collins, A., & Thew, N. (1999) Prostitution services: An exploratory empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 31, 1523-1529.

Cantu, L. (2002). A place called home: A queer political economy. In C. Williams & A. Stein (Eds.), Sexuality and gender (pp. 382-394). New York: Blackwell.

Carpenter, C. (2003). Sexual orientation and body weight: Evidence from multiple surveys. Gender Issues, 21, 60-74.

Carpenter, C. (2004). New evidence on gay and lesbian household incomes. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22, 78-94.

Carpenter, C., & Gates, G. (2008). Gay and lesbian partnership: Evidence from California. Demography, 45, 573-590.

Chauncey, G. (1994). Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books.

Clarkson, J. (2006). “Everyday Joe” versus “pissy, bitchy, queens”: Gay masculinity on StraightActing.com. Journal of Men’s Studies, 14, 191-208.

Cohan, D. L., Breyer, J., Cobaugh, C., Cloniger, C., Herlyn, A., Lutnick, A. et al. (2004, July). Social context and the health of sex workers in San Francisco. Paper presented at the International Conference on AIDS, Bangkok, Thailand.

Collins, A. (2004). Sexual dissidence, enterprise and assimilation: Bedfellows in urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 41, 1789-1806.

Collins, P. H. (1999). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Harper Collins.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Gender, black feminism and black political economy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 568, 41-53.

Connell, J. A. (2002, July). Male sex work: Occupational health and safety. Paper presented at the International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, Spain.

Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person, and sexual politics. Sydney, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Connell, R. W. (1992). A very straight gay: Masculinity, homosexual experience, and the dynamics of gender. American Sociological Review, 57, 737-751.

Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Sydney, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society, 19, 829-859.

Court, A. T. (1939). Hedonic price indexes with automotive examples. In General Motors Corporation, the dynamics of automobile demand (pp. 99-117). New York: General Motors Corporation.

Demetriou, D. Z. (2001). Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique. Theory and Society, 30, 337-361.

D’Emilio, J. D. (1997). Capitalism and gay identity. In R. Lancaster & M. di Leonardo (Eds.), The gender/sexuality reader (pp. 169-178). New York: Routledge.

Donaldson, M. (1993). What is hegemonic masculinity? Theory and Society, 22, 643-657.

Dorais, M. (2005). Rent boys: The world of male sex workers. London: McGill-Queens University Press.

Dowsett, G. W. (1993). I’ll show you mine, if you’ll show me yours: Gay men, masculinity research, men’s studies, and sex. Theory and Society, 22, 697-709.

Edlund, L., & Korn, E. (2002). A theory of prostitution. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 181-214.

Epple, D. (1987). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Estimating demand and supply functions for differentiated products. Journal of Political Economy, 95, 59-80.

Epstein, S. G. (2006). The new attack on sexuality research: Morality and the politics of knowledge production. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 3, 1-12.

Frankel, T. C. (2007, August 31). In Forest Park, the roots of Sen. Craig’s Misadventure. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Friedman, M. (2003). Strapped for cash: A history of American hustler culture. Los Angeles: Alyson.

Gertler, P., Shah, M., & Bertozzi, S. M. (2005). Risky business: The market for unprotected commercial sex. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 518-550.

Ginsburg, K. N. (1967). The “meat rack”: A study of the male homosexual prostitute. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 21, 170-185.

Giusta, M. D., Di Tommaso, M. L., & Strom, S. (2009). Who’s watching? The market for prostitution services. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 501-516.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: International.

Green, A. I. (2008a). The social organization of desire: The sexual fields approach. Sociological Theory, 26, 25-50.

Green, A. I. (2008b). Health and sexual status in an urban gay enclave: An application of the stress process model. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 436-451.

Griliches, Z. (1961). Hedonic price indexes for automobiles: An econometric analysis of quality change. In The price statistics of the federal government (pp. 173-196). New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hacker, H. M. (1957). The new burdens of masculinity. Marriage and Family Living, 19, 227-233.

Halvorsen, R., & Palmquist, R. (1980). The interpretation of dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. American Economic Review, 70, 474-475.

Han, C.-S. (2006). Geisha of a different kind: Gay Asian men and the gendering of sexual identity. Sexuality & Culture, 10, 3-28.

Hennen, P. (2005). Bear bodies, bear masculinity: Recuperation, resistance, or retreat? Gender and Society, 19, 25-43.

Herzog, D. B., Newman, K. L., Yeh, C. J., & Warshaw, M. (1991). Body image satisfaction in homosexual and heterosexual males. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11, 356-396.

Hoffman, M. (1972). The male prostitute. Sexual Behavior, 2, 16-21.

Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal, 39, 41-57.

Humphries, L. (1970). Tearoom trade: Impersonal sex in public places. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Itiel, J. (1998). A consumer’s guide to male hustlers. New York: Harrington Park Press.

Joffe, H., & Dockrell, J. E. (1995). Safer sex: Lessons from the male sex industry. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 5, 333-346.

Kaye, K. (2001). Male prostitution in the twentieth century: Pseudohomosexuals, hoodlums homosexuals, and exploited teens. Journal of Homosexuality, 46, 1-77.

Koken, J. A., Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2009). Male and female escorts: A comparative analysis. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: Prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry (2nd ed., pp. 205-232). New York: Routledge.

Koken, J. A., Parsons, J. T., Severino, J., & Bimbi, D. S. (2005). Exploring commercial sex encounters in an urban community sample of gay and bisexual men: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 17, 197-213.

Loftus, J. (2001). America’s liberalization in attitudes toward homosexuality. American Sociological Review, 66, 762-782.

Logan, T. D. (2010). Personal characteristics, sexual behaviors, and male sex work: A quantitative approach. American Sociological Review, 75, 679-704.

Logan, T. D., & Shah, M. (2009). Face value: Information and signaling in an illegal market (NBER working paper no. 14841). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Luckenbill, D. F. (1986). Deviant career mobility: The case of male prostitutes. Social Problems 33, 283-296.

MacDonald, L. A. (2007, September 2). America’s toe-tapping menace. New York Times.

Marlowe, J. (1997). It’s different for boys. In J. Nagle (Ed.), Whores and other feminists (pp. 141-144). New York: Routledge.

McBride, D. (2005). Why I hate Abercrombie and Fitch: Essays on race and sexuality. New York: New York University Press.

McNamara, R. P. (1994). The Times Square hustler: Male prostitution in New York City. Westwood, CT: Praeger.

Nagel, J. (2000). Ethnicity and sexuality. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 107-133.

Nardi, P. (Ed.). (2000). Gay masculinities. London: Sage.

Parker, M. (2006). Core groups and the transmission of HIV: Learning from male sex workers. Journal of Biosocial Science, 38, 117-131.

Parsons, J. T., Bimbi, D. S., & Halkitis, P. N. (2001). Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet. Journal of Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 8, 113-123.

Parsons, J. T., Koken, J. A., & Bimbi, D. S. (2004). The use of the internet by gay and bisexual male escorts: Sex workers as sex educators. AIDS Care, 16, 1021-1035.

Parsons, J. T., Koken, J. A., & Bimbi, D. S. (2007). Looking beyond HIV: Eliciting individual and community needs of male internet escorts. Journal of Homosexuality, 53, 219-240.

Pascoe, C. J. (2007). Dude, you’re a fag: Masculinity and sexuality in high school. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pettiway, L. E. (1996). Honey, honey, Miss Thang: Being black, gay and on the streets. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Phua, V. C., & Kaufman, G. (2003). The crossroads of race and sexuality: Date selection among men in internet “personal” ads. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 981-994.

Pompeo, J. (2009, January 27). The hipster rent boys of New York. New York Observer.

Pruitt, M. (2005). Online boys: Male for male internet escorts. Sociological Focus, 38, 189-203.

Reeser, T. W. (2010). Masculinities in theory. Oxford, England: Wiley Blackwell.

Reid-Pharr, R. F. (2001). Black gay man: Essays. New York: New York University Press.

Robinson, R. K. (2007). Uncovering covering. Northwestern University Law Review, 101, 1809-1850.

Robinson, R. K. (2008). Black “tops” and Asian “bottoms”: The impact of race and gender on coupling in queer communities (working paper). Los Angeles: UCLA.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 34-55.

Sadownick, D. (1996). Sex between men: An intimate history of the sex lives of gay men postwar to present. New York: Harper Collins.

Salamon, E. D. (1989). The homosexual escort agency: Deviance disavowal. The British Journal of Sociology, 40, 1-21.

Schrock, D., & Schwalbe, M. (2009). Men, masculinity, and manhood acts. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 277-295.

Scott, J. (2003). A prostitute’s progress: Male prostitution in scientific discourse. Social Semiotics, 13, 179-199.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). The epistemology of the closet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Simmel, G. (1971). Prostitution. In D. N. Levine (Ed.), On individuality and social forms (pp. 121-126). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Steele, B. C., & Kennedy, S. (2006, April 11). Hustle and grow. The Advocate.

Stein, A. (1989). Three models of sexuality: Drives, identities, and practices. Sociological Theory, 7, 1-13.

Uy, J. M., Parsons, J. T., Bimbi, D. S., Koken, J. A., & Halkitis P. N. (2004). Gay and bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet: Understanding reasons for and effects of involvement in commercial sex. International Journal of Men’s Health, 3, 11-26.

Varghese, B., Maher, J. E., Peterman, T. A., Branson, B. M., & Steketee, R. W. (2002). Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: Quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 29, 38-43.

Ward, J. (2000). Queer sexism: Rethinking gay men and masculinity. In P. Nardi (Ed.), Gay masculinities (pp. 152-175). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ward, J. (2008). Dude-sex: White masculinities and “authentic” heterosexuality among dudes who have sex with dudes. Sexualities, 11, 414-434.

Weinberg, M. S., & Williams, C. J. (1974). Male homosexuals: Their problems and adaptations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weitzer, R. (2005). New directions in research in prostitution. Crime, Law & Social Change, 43, 211-235.

Weitzer, R. (2009). Sociology of sex work. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 213-234.

West, D. J. (1993). Male prostitution. New York: Haworth Press.

Zelizer, V. A. (1994). The social meaning of money. New York: Basic Books.

Black

Black Blond

Blond Brown

Brown Gray

Gray Auburn/Red

Auburn/Red Other

Other Black

Black Blue

Blue Brown

Brown Green

Green Hazel

Hazel Hairy

Hairy Moderately Hairy

Moderately Hairy Shaved

Shaved Smooth

Smooth Athletic/Swimmer’s Build

Athletic/Swimmer’s Build Average

Average A Few Extra Pounds

A Few Extra Pounds Muscular

Muscular Thin/Lean

Thin/Lean Top

Top Bottom

Bottom Versatile

Versatile Safe

Safe