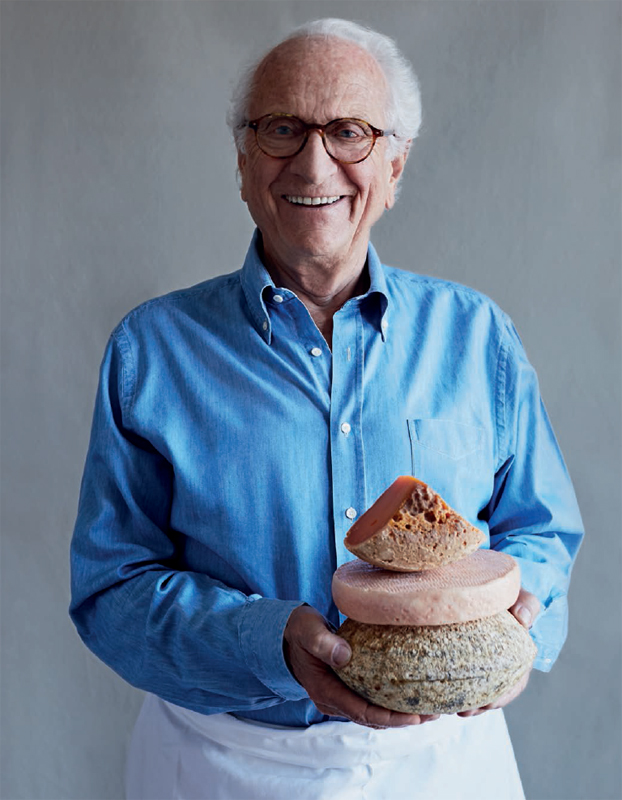

The numerous journeys I made through France while I was writing my last book, The Essence of French Cooking, rekindled many childhood memories for me, including, among others, my discovery and love of cheese… so much so, in fact, that I decided to devote my next book to the subject.

From the age of seven, my mother entrusted me with the task of buying a few items from the local market of St Mandé every Thursday. I would set off around midday to arrive when the stallholders were reducing their prices, preferring to sell their wares for less rather than having to pack everything up again. After buying fruit and vegetables, and some meat or fish, I was drawn like a magnet towards the cheese stall. The pleasure for me, as a kid, was an awakening of all my senses: smell, sight, touch and taste.

Every market day was invariably a voyage of discovery for me, because new cheeses appeared on the stall in different shapes, sizes and colours with the changing season, only to disappear again after a few months… I used to think that they wanted to play hide-and-seek with me. The woman on the stall would always spoil me. I think she loved seeing my face light up in front of the display of cheeses, my eyes devouring them all. She would give me little morsels to try, especially the fresh cheeses or any that were relatively mild on the palate while still being flavourful. Through her gentle handling, she succeeded in developing my palate.

Our finances didn’t allow us to spend a fortune on cheese, and my mother’s instructions were strict: I must use the few precious coins deep in my pocket to get maximum value for money. I would often pick Cantal, a cheese known at the time as ‘poor man’s cheese’, since it was the least expensive, yet nourishing, or a piece of Gruyère that, according to my mother, was vital for bone growth. Sometimes I’d choose a Camembert or half a Coulommiers, first checking it was perfectly ripe to the centre by pressing it with my thumb. A piece of Roquefort, the king of cheeses, was a real treat. It was expensive, so I would buy just a tiny piece – around 50g – to spread over a whole baguette to pass around the table and share on a Sunday.

So there you have it, that is how I discovered my love of cheese. Since then, of course, I have come across hundreds of types of cheese on my extensive travels around the world. And at our restaurant the Waterside Inn, we offer our clients a choice of between 30 and 40 cheeses every day.

It is thought that the first cheeses were made accidentally, thousands of years ago, as a consequence of herdsman carrying milk in leather bottles. Rennet, an enzyme found in a calf’s stomach, curdled the milk in the bottle, creating the earliest cheese. Over the centuries the process has, of course, been much refined, but it is still based on a simple technique, involving four basic ingredients: milk, a starter culture, rennet (or other curdling agent) and salt.

Cow’s milk is most commonly used, but cheese-makers also produce cheeses from goat’s, sheep’s and buffalo milk. Of the dozen or so dairy cattle breeds, the Holstein-Friesian is the most widespread. Dairy cows produce around 25 litres of milk a day each, and Germany is the biggest producer of cow’s milk in Europe.

France is the largest producer and consumer of goat’s cheese in Europe. Of the goat milking breeds, the Saanen is the best known. One goat produces between 2 and 5 litres a day, depending on the actual breed and its environs.

Sheep’s or ewe’s milk is naturally homogenised and richer in fat and protein than cow’s milk, making it ideal for cheese-making. One ewe produces around 1 litre of milk per day. The Lacaune breed is the most popular in France, which produces a wide variety of ewe’s cheeses, including the famous Roquefort. Greece, Italy and Spain also produce excellent cheeses from sheep’s milk.

Buffalo milk, from water buffalo, is primarily used to produce mozzarella. Italy is the main producer, of course, but good mozzarella is also produced in other countries around the world.

Whichever type of milk is used, the cheese-making process is similar. Firstly, a bacterial culture is added to the milk to acidify it. The bacteria turn the lactose in the milk to lactic acid, effectively souring it. Rennet or a non-animal curdling agent is then added to coagulate the milk, turning it into curds (the solid part) and whey (the liquid). The curds, which will become the cheese, are left to set and separate from the whey. This first stage forms the basis of the cheese.

The exact procedures during the subsequent stages determine the type or ‘category’ of cheese. With the exception of most of the fresh cheeses (see right), the second stage involves concentrating the curd. Firstly, to release the whey, the curds are cut – lightly for soft cheeses or finely for hard cheeses. After this, the curds are either ‘cooked’ or piled on top of each other and pressed to exclude more whey. The curd is then milled and salt is added.

The third and final stage is the ripening process, during which the flavour and texture of the cheese develops. This is achieved by storing the cheese for a certain length of time in an area where the temperature and humidity are controlled. The type of cheese determines the precise conditions and length of storage, which account for its individual characteristics.

Broadly, all cheeses belong to one of the following categories, according to the way they are produced:

Fresh cheeses These moist, young cheeses are ready to eat plain, just as they are, a few hours after being made. The curds are not cut, pressed or ripened (except for feta), so they represent the first stage of a cheese. Gently flavoured and low in fat, these milky cheeses are very mild and creamy, with just a hint of acidity. Ricotta, mozzarella and feta fall into this category, and there are many fresh goat’s cheeses.

Soft cheeses with a natural rind Often made in small log or pyramid shapes, these cheeses have a relatively fine rind covered in a light whitish to grey mould. They are mainly made from goat’s or sheep’s milk and tend to have a creamy texture and mild flavour. In fact, they are fresh cheeses that are left to age and dry out, often in temperature- and humidity-controlled caves, reaching maturity after 10 to 30 days. Fine examples include Sainte-Maure de Touraine, Crottin de Chavignol and Valençay.

Soft cheeses with a bloomy rind Made with cow’s, goat’s or sheep’s milk, these are surface-ripened and have a white rind casing. The flavour of these cheeses ranges from very mild (sometimes with light mushroomy and almond aromas), to fairly strong, and their texture from slightly granular to runny. My favourites are Normandy Camembert, Brillat-Savarin and Sharpham Brie.

Soft cheeses with a washed rind These cheeses are immersed in brine in various ways, which produces a relatively thin firm rind, ranging from yellow to orange. The brine curing gives their flavour more character too, resulting in fairly pronounced notes. Washed-rind cheeses also often undergo a slow ripening stage, which gives them a more distinctive and supple texture. Cheeses in this category include Vacherin Mont d’Or, Saint-Nectaire, Langres and Stinking Bishop.

Semi-hard cheeses As the name implies, these have a texture somewhere between soft and hard cheeses. These cheeses are pressed in moulds after the curd has been cut and ‘piled’. They are usually flavourful and fresh-tasting – even fruity – when young, becoming more pungent and firmer (but not hard) as they age. Fine examples are Gruyère, Pecorino and Gouda.

Hard cheeses These cheeses have been pressed to remove as much whey from the curds as possible, which ensures a long shelf life. They are matured for several months, at least. Firm, hard varieties, such as Parmesan and vintage Cheddar may be matured for as long as 24 months. They are often made in huge wheels, which can weigh up to 90kg. Examples include Parmesan, Comté, Beaufort and Cheddar (though this may be classified as a semi-hard cheese if it is relatively young).

Blue cheeses Ranging from mild to strong, these are veined cheeses, marbled with mould. The best-known blue cheeses made from cow’s milk are Gorgonzola and Stilton. Roquefort, known as the French king of cheeses, is made from sheep’s milk. The blue mould that develops inside the cheese is derived from the penicillin family. Moist blue cheeses are generally wrapped in foil so that the rind stays damp and sticky.

Flavoured cheeses These are hard or semi-hard cheeses that have fruit, spices and herbs added during the production process. The rind is often coloured, as in the Dutch Edam, Gouda and Nagelkaas. Popular flavoured cheeses in the UK are Cornish Yarg, Wensleydale with Cranberry and Double Gloucester with Chives. Smoked cheeses are assigned to this category.

Cheese quality classifications

In France there are over 1,000 different cheeses; in the UK there are now in excess of 700. Across the globe small artisan cheese-makers create an array of excellent cheeses, but, of course, most of the cheese on sale in supermarkets is mass-produced in factories. The way in which a cheese is produced determines its quality and price.

To help the consumer differentiate between cheeses, in terms of their production and quality, cheeses are designated to one of four classifications (appellations) in France:

• Farmhouse cheeses These are made from the milk on the farm premises within 24 hours of it being taken from the cow. The characteristics of the environment, or terroir, will produce a farmhouse cheese with a distinctive flavour. These are my favourite cheeses.

• Artisanal cheeses Producers of these cheeses use milk that comes from their own farm, possibly supplemented by milk from other nearby farms. These are often small enterprises. The cheeses are generally archetypal in flavour and are likely to be very good quality, without quite matching the pre-eminence of a farmhouse cheese.

• Cooperative cheeses These are produced in a dairy using milk that comes from several local farms. In some of these dairies the quantity of cheese produced is quite large.

• Industrial cheeses This is the largest and most common category. These cheeses are mostly mass-produced using pasteurised milk and are often destined for large-scale distribution. They have a standardised flavour and keep for longer than farmhouse or artisanal cheeses, but they do not hold any appeal for me.

Putting together a cheeseboard

First of all you need to take into account the season, particularly when it comes to your selection of fresh cheeses. The flavour and texture of a cheese is largely determined by the milk, the quality of which is affected by the food the animal is eating at the time. During the summer, cows, sheep and goats feed on pastures, which are generally lush at the start of the season, whereas their feed is largely hay during the winter months. Not surprisingly, fresh cheeses made in late spring and early summer tend to be more lively and interesting than those produced during the winter. This applies in particular to goat’s and sheep’s cheeses.

If possible, buy your cheese from a specialist cheese producer (in France a maître fromager) or cheese shop, or failing that from a supermarket or delicatessen that offers an extensive range of high-quality cheeses. A specialist cheese producer will have the advantage of an ageing cellar or cave (cave d’affinage) that can provide optimal conditions for the cheeses as they ripen. They will also be able to offer you the chance to sample a few cheeses that have caught your eye, and may even supply you with little labels to identify each different variety on your cheeseboard.

In a high-end restaurant, such as The Waterside, you will be offered a fine selection of cheeses and a knowledgeable waiter will be there to advise you. If you are entertaining at home, your choice will be determined largely by the number of guests. For four people, my advice would be to serve just one generous wedge of perfectly ripe cheese such as Brie de Meaux or Stilton, or a lovely piece of Comté. I always like to serve an odd, rather than even, number of cheeses. For six to eight guests, I’d probably offer five cheeses. For ten to twelve guests I would suggest serving seven cheeses at most, to avoid the choice becoming confusing.

Select a variety of cheeses from each the following categories:

• A fresh or white cheese, from the Loire valley, perhaps, where you can find a host of fresh goat’s cheeses between three and seven days old. There is also a wonderful little English goat’s cheese called Innes Button. This cheese will prepare your palate, much as in a wine tasting where you would start with a local wine before moving onto a premier cru, then a grand cru.

• A soft fresh cheese, with a natural rind such as a Saint-Pierre, Brocciu or Banon de Provence.

• A soft cheese with a bloomy rind, such as Sharpham Brie or Camembert.

• A soft cheese with a washed rind, such as Stinking Bishop, Vacherin Mont d’Or or Taleggio.

• A semi-firm hard cheese, such as Berkswell or Saint-Nectaire, or a hard cheese, such as Parmigiano Reggiano or Comté.

• A blue cheese, such as Gorgonzola, Stilton, Roquefort, Bleu des Causses or Fourme d’Ambert.

• A flavoured cheese, such as Cornish Yarg or Edam.

To appreciate their flavour to the full, cheeses should be served at room temperature. So, if they are stored in the fridge, you will need to take them out an hour or so before serving.

A cheese board should look appealing and have a sumptuous selection of cheeses, presented attractively. The actual board could be a large piece of slate, a beautiful piece of wood or a marble slab. If you have a few vine leaves or chestnut leaves to hand, you could use these to line the surface decoratively. Arrange some dried fruit (figs, apricots, dates, etc.), walnuts and hazelnuts around the cheeses.

On a separate dish, you could also offer a few little bunches of black or green grapes, some pears or apples, celery leaves, and a small dish of chutney. You can equally serve quince paste alongside, although it won’t necessarily go with every cheese, or a little honey, which would be a perfect accompaniment to Parmesan.

Don’t forget to provide several knives, to avoid using the same knife for all the cheeses. I also advise you to make a start on each cheese, as this will encourage your guests to dig in…

Offer an assortment of different breads: walnut, raisin or fig bread or even a lovely pain de campagne would go beautifully with your cheese. Provide a selection of biscuits too: water biscuits, very lightly sweetened oat biscuits and rye crackers, perhaps.

As for selecting a suitable wine or other drink to accompany cheese, there are no hard and fast rules. Red or white wine, vin jaune, whisky, sherry, port, Sauternes, cider and beer are all possibilities. It depends on the cheeses you have chosen to serve, and on your personal taste.

Savouring a cheeseboard with an appropriate drink is a wonderful, relaxing way to end a meal, but if you are serving a dessert you may prefer to offer the cheese first, as a palate-cleanser before the sweet finale. This is the tradition in France but the choice is yours.

If you want to amaze your friends, you could make cheese the focus of your meal. Try offering a tasting menu comprised entirely of cheeses, with a selection of seven to nine, from the mildest type to the strongest, each one accompanied by a different, appropriately selected drink. You might like to serve a few extra things alongside, such as cherry tomatoes, canapés, salami, etc… as well as a green salad dressed with a not-too-sharp lemon vinaigrette.

Cheese keeps best in its original paper or box, or wrapped in baking parchment or waxed paper. Avoid wrapping cheese in cling film, which forms a tight seal and prevents it from ‘breathing’, which has an adverse effect on the flavour. Vacuum-packed cheeses are convenient if you are travelling, but you should take them out of the vacuum pack as soon as you arrive at your destination, to let them breathe.

Some cheeses need cooler storage than others. Fresh cheeses need to be kept in the fridge. Soft and blue cheeses require cooler storage than hard cheeses, which are best kept in a cool larder (between 8 and 15°C). Ideally soft and blue cheeses should be stored between 5 and 8°C, or in the least cold part of the fridge (usually the salad drawer).

Don’t forget to take cheese out of the fridge at least an hour before serving, and to trim the cut edges if they have already been started.

Savouring cheese in its natural state – on its own, or with good bread or biscuits and perhaps a little fruit – is always a pleasure for me, but it is creating recipes with cheese that excites me the most. This is an ingredient that has so much to offer, in terms of flavour, texture and versatility. It is an essential component of many great classic dishes: fondue, gnudi, tartiflette and a host of omelettes, soufflés and pasta recipes. And it gives an incomparable savouriness to so many canapés, salads and snacks.

As I have developed and tested the recipes for this book, it has never failed to amaze me how the appropriate cheese can take a dish to new heights. It deepens and intensifies the taste of so many vegetable and meat dishes, adding to their nutritional value at the same time. After all, cheese is an excellent source of protein, B vitamins and minerals, especially calcium.

Some of the pairings are surprising too. Fish, for example, isn’t an ingredient you would naturally put with cheese, but the combination can be sublime: try my grilled halibut steak with Parmesan and ginger hollandaise and you will believe me!

Even a little well-flavoured cheese can enhance a dish. At the most minimal level, I use it as a seasoning – like salt and pepper – to fine-tune many dishes. I hope my recipes will encourage you to explore the world of cheeses through cooking… there is so much to savour and enjoy. Bon appetit!