Introducing performance measurement

A performance measurement system is an organised means of defining measures of performance and gathering, recording and analysing information to monitor performance against objectives, identify areas for improvement and take action to improve performance as necessary.

A key performance indicator (KPI) is a measure against which the management of any activity can be assessed. Measurement against the indicator enables managers to assess how efficiently, effectively or cost-effectively the operation is performing.

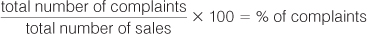

Performance measures provide a quantitative answer to whether you are reaching or exceeding targets. They require the collection of raw data and conversion through a formula into a numerical unit. For example, a target may have been set to reduce the proportion of customer complaints from 10% of total sales to 5% (the indicator). A formula to see whether this has been achieved would look like this:

Performance measures are used to assist in tracking organisational performance against objectives. Any system of performance measurement must be fully aligned with the organisational mission, strategy and values, and be integrated into the overall system of performance management that sets and monitors the achievement of organisational, departmental, team and individual objectives.

To evaluate the performance of an organisation or department, credible and reliable measures need to be in place. This checklist provides some principles to help managers introduce or improve performance measurement in their organisation and considers such questions as what to measure, how to measure it, what targets to set, how to gather, record and analyse performance information, and how to take action on the results.

Effective performance measurement can identify areas for improvement, help to keep performance on track, alert the organisation to potential threats, and enable managers to make decisions based on reliable results rather than instinct. Meaningful and actionable data can be a powerful tool for influencing behaviour and keeping one step ahead of the competition. To establish a successful performance measurement, processes, time, resources and planning are required.

Measuring performance has many advantages and enables an organisation to:

- understand the current position

- predict future financial performance

- maintain a record of historical performance

- identify strengths and weaknesses

- determine whether improvements have actually taken place

- establish a programme to benchmark against competitors, other organisations or previous results.

The financial measures traditionally used as a means of performance accounting are now more commonly balanced with non-financial measures, such as customer satisfaction and on-time delivery, to gain a more rounded picture of overall performance.

1 Designate those responsible for the performance measurement system

This should include members drawn from all levels and departments of the organisation who will be responsible for the design, implementation, management and review of performance measures. Appoint a coordinator (someone with project management experience who commands respect and can get things done) to oversee the system.

2 Ensure the support of employees

Senior management must fully support the system from the outset. Without their support it will be more difficult to instigate change and influence decision-making based upon the results of the measures.

It is equally important to win the support and cooperation of all other employees. Achieve this by explaining clearly why a performance measurement system is being introduced. Highlight the benefits that effective performance measurement will bring, emphasising it as a positive exercise. Be prepared for a negative reaction from employees who may view it as a form of personal monitoring. Allay anxiety by communicating the process clearly, openly and honestly, gaining buy-in from its inception. Provide an opportunity for employees to raise any concerns they may have.

3 Identify the activities to be measured

The selection of the right measures is crucial, as the relevance of the results will depend on what is measured.

Questions that should be considered when deciding what and how to measure performance include:

- What products or services do we provide?

- Who are our customers and stakeholders (internal and external)?

- What do we do?

- How do we do it?

Think about the activities that contribute to the achievement of organisational goals and are essential for success. Resist the temptation to focus solely on measures where you know that the organisation will score highly.

The number of activities to be measured will vary, but as a guide the key performance areas typically cover financial, market, environment, operations, people and adaptability. Avoid measuring too many activities for the sake of it – this will simply create an overwhelming set of results that will cause confusion and be difficult to analyse and act upon. It is helpful to place activities in order of priority to ensure that the main drivers of success are acted upon first.

4 Establish key performance indicators

Once the activities have been defined it is necessary to identify what information is required in relation to each one. What does success look like and what level of performance needs to be achieved? Which indicators will best reflect the key success factors? For each of the critical activities selected for measurement, it is necessary to establish a key performance indicator (KPI).

Good performance indicators are:

- realistic – they do not require unreasonable effort to meet

- understandable – they should be expressed in simple and clear terms

- adaptable – they can be changed if conditions change

- economic – the cost of setting and administering should be low in relation to the activity covered

- legitimate – they should be in line with or exceed legislative requirements

- measurable – they should be communicable with precision.

A period of observation may be appropriate if it is the first time an indicator is to be established for an activity. Similar organisations may be prepared to offer information on the targets they set; this can then be used to establish your own indicators. From the performance indicator you will be able to identify what data need to be collected.

5 Provide a balanced set of measures

Linking measures to key success factors is critical to effective performance measurement, and introducing a balance of financial and non-financial measures offers the flexibility to achieve this. A company’s success is often judged by how it performs financially, so traditional financial measures are valuable for senior managers and external stakeholders. However, many performance aspects, such as customer satisfaction, product quality and delivery times, simply cannot be captured by financial measures alone. For many employees, operational and non-financial measures are more easily aligned with personal objectives, and thus help in gaining valuable employee support for performance measurement. Use both forms of measurement to get a complete picture of overall performance.

6 Collect the data

Once the measures have been decided and agreed, the next step is to determine how the data will be collected and by whom. Ask yourself:

- What am I trying to measure?

- Where will I make the measurement?

- How accurate and precise must the measurements be?

- How often do I need to take the measurement?

For activities that are undertaken frequently it may be feasible for only a sample measure to be taken, say at every eighth event. In many cases the data required for the performance measurement will already exist, for example in databases or log books. There will be instances where an automated data collection system can or should be installed to provide accurate data without the need for human intervention.

As appropriate, inform individuals when they should start collecting data and in what format it should be presented: graphs, tables, datasheets or spreadsheets, and so on. All the data should be passed on to those responsible for analysis.

7 Implement the system with care

Introducing and launching new performance measures is a major operation. Adequate time and resources need to be available in advance to ensure a smooth launch and minimise disruption. Communicate the timescale for implementation widely and make sure that everyone is fully aware of its intended format and use. Carrying out a pilot or ‘soft’ launch will help you identify any potential problems.

8 Analyse the data

Before drawing conclusions from the data, verify that:

- the data appear to answer the questions that were originally asked

- there is no evidence of bias in the collection process

- there is enough data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Once the data have been verified the required performance measurement can be formulated. This may involve the use of a computer spreadsheet if there is a large amount of data. The results of the performance measures should be compared with the indicator set for each activity.

9 Consider whether the indicators need to be adjusted

Once the indicators have been analysed the following may be observed:

- the activity is underperforming – the indicator should be left as it is, but the reasons for failure should be identified and action taken to remedy the situation

- variance is not significant – a higher indicator should be set to achieve continuous improvement

- the indicator is easily achieved – if indicators are not challenging, continuous improvement is unlikely to be encouraged.

Consider how to adjust the indicators in order to gather meaningful data and put the necessary amendments in place.

10 Communicate the results

Summarise the data and prepare a report by following these steps:

- categorise the data and use graphs to show trends

- make the report comparative to goals or standards

- make sure all performance measurements start and end in the same month or year

- adopt a standard format by using the same size sheets and charts

- add basic conclusions.

Share the findings of the report widely both with internal employees and external stakeholders. Do not be tempted to gloss over negative results or, worse still, ignore them. Communication needs to be consistent, timely, accurate and unbiased. Only then will performance measurement become credible and useful.

Choose the most appropriate communication channel to suit the audience – email, intranet, newsletter, or formal presentation or meeting. Consider communicating positive results to suppliers or customers too as a means of promotion – for example, that 99% of customers rate the products as excellent. It may be beneficial to follow up the distribution of data with a workshop to make sure that everyone understands the implications of the results.

Identify areas for improvement and consider what steps may be needed to achieve improvements. Negative results may raise awareness of issues that may have been largely unknown, or confirm what was suspected. Positive results can also be used to make further improvements. Even good practice can be improved upon, so avoid complacency and utilise the results to continue to make innovative improvements. Discuss the need for changes with relevant individuals, assign responsibility for action and monitor recommended improvements. Equip employees with the tools and resources required, and consider whether training or development are needed.

12 Continue to measure performance and evaluate performance measures

The process of collecting data and analysing performance should be continuous. Goals and standards should be increased as performance improves, or adjusted as activities change. Measures will only be relevant for as long as the activity being measured remains the same. Aim to review each set of measures at least annually to ensure that they remain relevant. Consistency in the testing and measurement of different activities will help to track performance over time.

As a manager you should avoid:

- failing to align performance measures with organisation strategy and objectives

- setting performance measures in stone – modify them as processes and activities change

- failing to act on the results of performance measurement

- underestimating the resources (staff and time) that measuring performance will consume

- introducing too many measures.

Implementing the balanced scorecard

The balanced scorecard is defined as a strategic management and measurement system that links strategic objectives to comprehensive indicators. The key to the success of the system is that it must be a unified, integrated set of indicators that measure the activities and processes at the core of an organisation’s operating environment.

The balanced scorecard takes into account not only the traditional ‘hard’ financial measures but also three categories of ‘soft’ quantifiable operational measures:

- financial perspective – timely and accurate financial data are essential

- customer perspective – how an organisation is perceived by its customers

- internal perspective – areas in which an organisation must excel through business process improvements

- innovation, learning and growth perspective – supported by knowledge management activities and initiatives, areas in which an organisation must improve and add value to its products, services, or operations.

Measurements taken across these four categories are seen to provide a rounded balanced scorecard that reflects organisational performance more accurately than one based solely on financial indicators. This in turn assists managers to focus on their mission, rather than merely on short-term financial gain. It also helps to motivate staff to achieve strategic objectives.

Traditionally, managers have used a series of indicators to measure how well their organisations are performing. These measures relate essentially to financial aspects such as business ratios, productivity, unit costs, growth and profitability. While useful in themselves, they provide only a narrowly focused snapshot of how an organisation performed in the past and give little indication of likely future performance.

During the early 1980s, the rapidly changing business environment prompted managers to take a broader view of performance. Consequently, a range of other factors started to be taken into account, exemplified by the McKinsey 7-S model and popularised by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman’s book, In Search of Excellence. These provide a broader assessment of corporate health in both the immediate and the longer term. This checklist focuses on the balanced scorecard, which was developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton in the early 1990s with the aim of providing a balanced view of an organisation’s performance.

The balanced scorecard has become an increasingly popular performance management and measurement framework and regularly appears in the top ten in Bain & Company’s most used annual management tools surveys.

Kaplan and Norton identified a number of stages for implementing the scorecard. These include a mix of planning, interviews, workshops and reviews. The type, size and structure of an organisation will determine the detail of the implementation process and the number of stages adopted. This checklist outlines some of the main steps.

Action checklist

1 Be clear about organisational strategy and objectives

As the scorecard is inextricably linked to strategy, the first requirement is to clearly define the strategy and make sure that senior managers, in particular, are familiar with the key issues. Before any other action can be planned, it is essential to have an understanding of:

- the strategy

- the key objectives or goals required to realise the strategy

- the three or four critical success factors (CSFs) that are fundamental to the achievement of each major objective or goal.

Starting with strategy and objectives is crucial and will help organisations avoid doing the wrong things really well.

2 Develop a strategy map

Strategy mapping is a tool developed by Kaplan and Norton for translating strategy into operational terms. A strategy map provides a graphical representation of cause and effect between strategic objectives and shows how the organisation creates value for its customers and stakeholders. Generally, improving performance in the objectives under learning and growth enables the organisation to improve performance in its internal processes, which in turn enables it to create desirable results in the customer and financial perspectives.

3 Decide what to measure

Once the organisation’s major strategic objectives have been determined, a set of measures can be developed. The measures chosen must reflect the strategic objectives and help to align action with strategy. As a guide, there should be a limit of 15–20 key measures linked to those specific goals (significantly fewer may not achieve a balanced view, and significantly more may become unwieldy and deal with non-critical issues).

Based on the four main perspectives suggested by Kaplan and Norton, a list of goals and measures may include some of the following:

Financial (shareholder) perspective

- Goals – increased profitability, growth, increased return on their investment

- Measures – cash flows, cost reduction, economic value added, gross margins, profitability, return on capital, equity, investments and sales, revenue growth, working capital, turnover

Customer perspective

- Goals – new customer acquisition, retention, extension, satisfaction

- Measures – market share, customer service, customer satisfaction, number of new, retained or lost customers, customer profitability, number of complaints, delivery times, quality performance, response time

Internal perspective

- Goals – improved core competencies, improved critical technologies, reduction in paperwork, better employee morale

- Measures – efficiency improvements, development, lead or cycle times, reduced unit costs, reduced waste, amount of recycled waste, improved sourcing/supplier delivery, employee morale and satisfaction, internal audit standards, number of employee suggestions, sales per employee, staff turnover

Innovation and learning perspective

- Goals – new product development, continuous improvement, employee development

- Measures – number of new products and percentage of sales from these, number of employees receiving training, training hours per employee, number of strategic skills acquired, alignment of personal goals with the scorecard

4 Amend the scorecard if appropriate

Each organisation must determine its own strategic goals and the activities to be measured. Some organisations have found that Kaplan and Norton’s template fails to meet their particular needs and have either modified it or devised their own scorecard. Public-sector organisations, for example, may have different aims and objectives and may have to tailor the scorecard to reflect this.

One way to do this, to reflect the fact that people are a major cost item and also a major driver of value, is as follows:

- financial – as above

- customer – as above

- internal – concentrating on systems and processes

- people – focusing on leadership, learning and development, performance management, employee engagement etc.

5 Finalise the implementation plan

Further discussions, interviews and workshops may be required to fine-tune the detail and agree the strategy, goals and activities to be measured, ensuring that the measures selected focus on the critical success factors. At this stage, it is critical to be clear about what ‘good’ looks like.

It may be worth identifying the key business processes, and drawing up a matrix of key business processes and critical success factors. Key business processes that have an impact on many critical success factors should attract more attention and improvement efforts than those that influence few or no critical success factors.

Before implementation, targets, rates and other criteria must be set for each of the measures, and processes for how, when and why the measures are to be recorded should be put in place.

An implementation plan should be produced and the whole project communicated to employees. Everyone should be informed at the beginning of the project and kept up-to-date on progress. It is crucial to communicate clearly with employees. Explain the purpose and potential benefits of the system to them and make sure that everyone is aware that they have a role to play in achieving corporate goals. There should be a ‘golden thread’ linking personal objectives to organisational goals. Ideally, this will be achieved through an organisational performance management system.

The system for recording and monitoring the measures should be in place and tested well before the start date, and, as far as possible, training in its use should be given to all users. The system should automatically record all the data required, though some of the measurements may need to be input manually.

7 Publicise the results

The results of all measurements should be collated regularly: daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, or as appropriate. This will potentially comprise a substantial amount of complex data, and you need to decide who will have access to the full data: senior management only, divisional or departmental heads, or all employees. Alternatively, partial information may be provided on a need-to-know basis. Decide how the results will be publicised – through meetings, newsletters, the organisation’s intranet or any other appropriate communication channels.

8 Utilise the results

Any form of business appraisal is not an end in itself. It is a guide to organisational performance and may point to areas (management, operational, procedural) that require strengthening. Taking action based upon the obtained information is as important as the data itself. Indeed, management follow-up action should be seen as an essential part of the appraisal process.

9 Review and revise the system

After the first cycle has been completed, a review should be undertaken to assess the success, or otherwise, of both the information gathered and the action taken, in order to determine whether any part of the process requires modification.

Refrain from using the same scorecard measures year after year. Review the existing measures and, where appropriate, remove flawed measures and replace them with more reliable ones. Be prepared to introduce additional measures to reflect current circumstances, for example to measure an organisation’s ethical performance.

As a manager you should avoid:

- setting measures that do not relate to critical success factors

- over-measuring the organisation

- allowing the measurement process to interfere with employees’ ability to get on with the job

- adopting an off-the-shelf system not suited to the organisation.

Robert Kaplan and David Norton

The balanced scorecard

Introduction

Robert Kaplan (b. 1940) and David Norton (b. 1941) are jointly recognised as popularisers of the balanced scorecard and their approach to it was first introduced in a 1992 Harvard Business Review article, ‘The Balanced Scorecard: Measures that Drive Performance’. Kaplan and Norton turned the popular saying ‘What gets measured gets done’ on its head and began with ‘What you measure is what you get’.

Kaplan studied at MIT, where he gained a BS and an MS in electrical engineering, and then at Cornell University, where he gained a PhD in operations research. He then spent sixteen years on the faculty of Carnegie-Mellon University, serving as dean from 1977 to 1983. He moved on to Harvard Business School in 1984 and is now Baker Foundation Professor. Kaplan has received a number of awards and in 2006 he was elected to the Accounting Hall of Fame.

David Norton is a consultant, researcher and speaker in the field of strategic performance management. He is the founder and director of Palladium Group, a professional services firm focusing on performance measurement and management. Previously he worked at Renaissance Solutions, a consulting company that he co-founded with Kaplan in 1992, and at Nolan, Norton & Company, where he was president for sixteen years.

The balanced scorecard is an aid to developing and managing strategy by looking at how key measures interrelate to track progress. Kaplan and Norton argue that adherence to quarterly financial returns and the bottom line alone will not provide organisations with an overall strategic view. The balanced scorecard, though, goes beyond the exploitation of financial measures alone by incorporating three other key perspectives:

- a customer perspective – which addresses how customers see the organisation

- an internal business perspective – which requires the organisation to identify that at which it needs to excel

- a learning/innovation perspective – which addresses what the organisation needs to improve to create value in the future.

By commenting on the present and indicating the drivers of the future, the scorecard both measures and motivates business performance.

Setting up the balanced scorecard

Kaplan and Norton argue that strategies often fail because they are not converted successfully into actions that employees can understand and apply in their everyday work. It is difficult to formulate realistic measures that are meaningful to those doing the work, relate visibly to strategic direction and provide a balanced picture of what is happening throughout the organisation, not just one facet of it. It is this aspect that the balanced scorecard addresses.

The balanced scorecard concentrates on measures in four strategic areas – finance, customers, internal business processes and learning and innovation – and requires the implementing organisation to identify goals and measures for each of them. For a detailed breakdown of these four areas, see the ‘Implementing the balanced scorecard’ checklist, page 182.

The scorecard provides a description of the organisation’s strategy. It will indicate where problems lie because it shows the interrelationships between goals and linked activities. It creates an understanding of what is going on elsewhere in the organisation and shows all employees how they are contributing. Providing that accurate and timely information is fed into the system, it helps to focus attention on where change and learning are needed through the cause-and-effect relationships it can reveal. Examples of the types of insight achieved were detailed in Linking the Balanced Scorecard to Strategy:

If we increase employee training about products, then they will become more knowledgeable about the full range of products they can sell;

If employees are more knowledgeable about products, then their sales effectiveness will improve;

If their sales effectiveness improves, then the average margins of products they sell will increase.

Implementing the balanced scorecard

In Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work, Kaplan and Norton identify eight steps towards building a scorecard:

1 Preparation. Select/define the strategy/business unit to which to apply the scorecard. Think in terms of the appropriateness of the four main perspectives defined above.

2 First interviews. Distribute information about the scorecard to senior managers along with the organisation’s vision, mission and strategy. A facilitator will interview each manager on the organisation’s strategic objectives and ask for initial thoughts on scorecard measures.

3 First executive workshop. Match measures to strategy. The management team is brought together to develop the scorecard. From agreeing the vision statement, the team debates each of the four key strategic areas, addressing the following questions:

- If my vision succeeds, how will I differ?

- What are the critical success factors?

- What are the critical measurements?

These questions help to focus attention on the impact of turning the vision into reality and what to do to make it happen. It is important to represent the views of customers and shareholders and gain a number of measures for each critical success factor.

4 Second interviews. The facilitator reviews and consolidates the findings of the workshop and interviews each of the managers individually about the emerging scorecard.

5 Second workshop. Team debate on the proposed scorecard; the participants discuss the proposed measures, link ongoing change programmes to the measures, and set targets or rates of improvement for each of the measures. Start outlining the communication and implementation processes.

6 Third workshop. Final consensus on vision, goals, measures and targets. The team devises an implementation programme on communicating the scorecard to employees, integrating the scorecard into management philosophy, and developing an information system to support the scorecard.

7 Implementation. The implementation team links the measures to information support systems and databases and communicates the what, why, where and who of the scorecard throughout the organisation. The end-product should be a management information system which links strategy to the shop-floor activity.

8 Periodic review. Balanced scorecard measures can be prepared for review by senior management at appropriate intervals.

Since the publication of their first book on the balanced scorecard, Kaplan and Norton have continued to develop their ideas and clarify how they can be implemented to maximum effect. In The Strategy-Focused Organization, they looked at how companies were using the scorecard and identified five principles for translating strategy into operational terms and aligning management and measurement systems to organisational strategy. A third book, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Intangible Outcomes, introduced the concept of ‘strategy maps’, which provide a visual framework for describing how value is created within organisations from each of the four balanced scorecard perspectives. Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Strategies looks at how to align organisational business units to overall strategy and how to use a strategy map to clarify and communicate corporate priorities to all business units and their employees.

A later book, published in 2008, The Execution Premium: Linking Strategies to Operations for Competitive Advantage, explores this theme further, focusing on how to put strategy into action to achieve financial success.

In perspective

The balanced scorecard can be seen as the latest in a long line of attempts at management control, starting with F. W. Taylor and continuing through work measurement systems, quality assurance systems and performance indicators. Commentators suggest that the scorecard is flexible and can be adapted for use by individual organisations, and it is practical, straightforward and devoid of obscure theory. Most importantly, it responds to many organisations’ requirements to expand strategically on traditional financial measures and points to areas for change. It is also used successfully in the public sector, where the focus is on organisational mission rather than financial return for shareholders.

The balanced scorecard has become increasingly popular. Bain & Company’s 2007 survey of management tools suggests that 66% of companies are using it worldwide, with usage highest in Asia and in large companies.

However, the level of satisfaction with the tool has declined since the previous survey and is now below the average for the tools covered by the survey. In The Design and Implementation of the Balanced Business Scorecard: an Analysis of Three Companies in Practice, Stephen Letza suggests that it cannot be regarded as a panacea. He states that the balanced scorecard should highlight performance as a continuous, dynamic and integrated process, act as an integrating tool, function as the pivotal tool for an organisation’s current and future direction, and deliver information that is the backbone of the strategy. He also highlights some of the major drawbacks in using the balanced scorecard and points out the need to:

- avoid being swamped by the minutiae of too many detailed measures and make sure that measures relate to the strategic goals of the organisation

- make sure that all activities are included – this ensures that everyone is contributing to the organisation’s strategic goals

- watch out for conflict as information becomes accessible to those not formerly in a position to see it and try to harness conflict constructively.

Kaplan and Norton have attempted to ensure that the scorecard is used correctly through their provision of education and consultancy programmes and by establishing a Hall of Fame, which showcases companies that have successfully implemented the balanced scorecard.