In Chapter 4, I made it clear that low-FODMAP eating is not meant to be forever. This chapter will walk you through the two phases of the program: phase one, the two- to six-week elimination round, and phase two, when you will begin to reintroduce some of the foods you’ve removed to find out what you can tolerate.

Commit to the plan by eating nothing but Go foods for two to six weeks. Lists of the foods you can eat and the amounts that are OK during this phase begin under Go Foods. You can also include Slow foods, as long as you proceed with extreme caution and take extra care to keep the portion sizes small. Sound hard? Well, there’s no doubt that it’s a challenge. But you can also consider it an adventure. It’s kind of like going away to summer camp. So you have to take a break from Snapchat for a few weeks. But, you know it will be there waiting for you when you get back—and in its absence, you may discover some cool things along the way (like real live friends! Or, in the case of the Go Low plan, lactose-free yogurt!).

Your favorite foods, too, will still be there when you finish up phase one of the Go Low plan—but I’ll give you so many delicious ideas that, guaranteed, you’ll want to continue eating them after you’re long done with this stage. Not to mention, eating these low-FODMAP foods just may get you feeling better, which will motivate and inspire you to stick with it.

Easy peasy, right? You probably read through the delicious-sounding meal and snack options in Chapter 4 and didn’t even notice that garlic, hummus, ice cream, and bagels are off-limits. Er, you did? OK, well, here’s my advice: Focus on what you can eat, and the foods you can’t have will fade into the distance. And for those moments when you can’t simply forget what you’re missing out on, remind yourself that this is temporary and that the goal is not for you to be miserable but for you to feel great.

If it feels like a lot, fear not—as soon as this initial phase is over, we won’t waste any time getting you to experiment with No foods to see what you can tolerate. In the meantime, try something different, like my Chocolate-Covered Strawberry Shake or Happy Belly Breakfast Tacos, or ask your parent to pick up a new-to-you low-FODMAP food like star fruit at the exotic fruit market. Making it fun helps you stick with it so you can finally get the relief you deserve.

Once you’ve lived Go Low phase one, the elimination for two to six weeks, and have found relief from your symptoms (I hope!), it’s time to test the higher-FODMAP foods so you can expand your eating options. Remember, it’s not that you can never eat FODMAP-containing foods again—you just need to make sure you’re not eating too much of the ones that put you over the edge. All it takes is a little experimentation and patience to figure out how to enjoy some of the foods you’re missing without retriggering those nasty symptoms.

Take phase two, the No Challenge, one step at a time. Once you’ve found relief from your symptoms during phase one of Going Low, you can rest there for a few weeks and enjoy feeling good. But by week six, it’s time to begin experimenting. As soon as you feel you’re ready, here’s how it works.

Choose one class of FODMAPs to experiment with (this isn’t a pop quiz—you can refresh your memory by taking a look here). Try one typical serving of a food that’s high in that class of FODMAP and that class of FODMAP only—your best bet is to stick with the challenge foods that I’ve suggested under What Food Should I Start With?.

Step two is a three-day test. Here’s what you’ll do:

Day 1: Add a food containing the FODMAP you’ve decided to experiment with to only one meal, in the amount recommended. Feeling good? Great. Now, sleep on it and see how you feel the next morning. Still good? Great.

Day 2: Have the same food again—this time, double the amount you ate yesterday. Still feeling good? Awesome!

Day 3: If you’re still in good shape, eat the food once again in the same amount you had on day 2. Doesn’t seem to bother you? Then you’re in the clear with this food and can include it in your diet in moderate amounts.

If at any point during this trial period you begin to experience symptoms again, simply drop the new food and skip immediately to step three, eating just a baseline Go Low diet for three or more days, until you feel better.

For step three, go back to your baseline diet—in other words, eat only what’s OK during Go Low phase one and don’t eat any of the newly introduced foods—for three days. Even though you ruled out the food that you just tried as something that’s giving you major problems, there’s still some fine-tuning to do here—for instance, you may tolerate small amounts of dairy and beans on their own, but not at the same meal. So to get the best picture of how your body handles each FODMAP individually, you’ll want to go back to your basic diet before you test a new food.

Now, pick a new food to try, and start with step one all over again!

Remember: During the No Challenge, you want to introduce as many foods as possible to give your diet the most variety and stick-with-it-ability (that’s a technical term). However, the object is getting you well. If you start to experience symptoms after introducing any new food, don’t push it. Put it on the back burner—you can always revisit it in different amounts later on in the process.

So let’s say you want to start with fructose. A good food to challenge with would be honey. Add a serving of honey—1 teaspoon—to a cup of approved herbal tea or plain lactose-free yogurt on day one. No symptoms? Great. On day two, do the same thing, but this time with 2 teaspoons. If all is well, on day three have the same, 2 teaspoons. If you continue to feel good, you now know that fructose (in moderation) is not your problem. Unpleasant symptoms? We have a culprit. You can stop here and go back to your baseline diet. Three or more days later, when you’re feeling well again, test out a different FODMAP.

Because many high-FODMAP foods contain a combination of FODMAPs, use the foods in this table as your challenge foods—this way you’ll more easily pinpoint which FODMAP is giving you the trouble.

The one you miss the most—although don’t get too excited; you’re going to have to wait until you’ve completed testing each class of foods before you can begin eating it regularly again (if all goes well).

Yes. There’s no right time of day to reintroduce a food, but do try to do it earlier rather than later—with breakfast or lunch, or at latest an afternoon snack—so that you won’t snooze through any symptoms.

If you eat a late dinner with your first clove of garlic in six weeks and then head straight to bed, you might be deep in slumber when gas and bloating hit. And granted, if you’re sleeping through symptoms, they may not be that bad; however, for the purpose of exploration, it probably makes sense to be conscious when you’re most likely to feel something, right?

Yes—it won’t hurt your experiment to do so, and it just might help you get to the bottom of things. If you have a cup of tea with honey in it on day one, a smoothie on day two, and a bowl of oatmeal on day three, it will be harder to tell what’s causing your symptoms in the event that you start feeling unwell. Try to have the same food three days in a row in the same way, preferably along with a food you’ve eatenregularly with no problem while on the Go Low plan—honey in a 3-ounce (85 g) serving of lactose-free yogurt, for instance. Minimizing the number of variables will help you easily identify the causes of your tummy troubles.

|

FODMAP |

DAY ONE |

DAY TWO + DAY THREE |

|

Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), vegetables |

½ clove garlic |

1 clove garlic |

|

Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), grains |

1 slice of wheat bread |

2 slices of wheat bread |

|

Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) |

¼ cup (50 g) canned kidney beans |

½ cup (100 g) canned kidney beans |

|

Polyols (mannitol) |

¼ cup (18 g) button mushrooms |

½ cup (35 g) button mushrooms |

|

Polyols (sorbitol) |

1 medium apricot or 3 blackberries |

2 medium apricots or 6 blackberries |

|

Lactose |

½ cup (120 ml) milk |

1 cup (240 ml) milk |

|

Fructose |

1 teaspoon honey |

2 teaspoons honey |

Sad to say, but, no. Because portion size matters, it’s crucial that you test out foods in moderate amounts to see what you can tolerate. To do that, you need full control in the kitchen. A bowl of pasta at a restaurant is way too big and too likely to cause symptoms to get a handle on what you might be able to eat. Onion rings, delicious though they are, are also battered with flour and drenched in oil—adding several new variables that you might react to. Stay home (for now), and keep it simple.

Try the same food; however, this time you’ll want to start with half the amount you started with last time. Experienced gas and bloating from that 1 teaspoon honey? Try ½ teaspoon next time. Remember, much of your tolerance for FODMAPs depends on portion size—so there’s a decent chance you’ll find that you’re OK with a super small amount. It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s helpful for you to get a handle on what you can get away with before your gut begins to revolt. FODMAP researchers say it’s unlikely that you’ll have to completely eliminate a food.

You really shouldn’t. First of all, eating according to the Go Low elimination plan can get boring—sure, I’ve done everything I can to make it as interesting as possible, but there’s no doubt that it’s a limited way of eating that can be a burden on your social life and family relationships. But more important, while going on a low-FODMAP diet may diminish your gut symptoms, it may also have a negative impact on your gut microbiome, which isn’t good for your overall health, according to research from Australia. FODMAP scientists have said that their results have shown how important it is to ease up on restrictions and vary the diet as much as possible, as soon as possible.

If you’re like most teenagers, the responsibility of shopping for groceries and cooking probably falls on one or both of your parents. Sound familiar? Well, the two to six weeks that you’re in phase one of the Go Low plan is a great time to get familiar with how your meal gets from wherever the food came from to landing on your plate. The reason: Just by reading this book, you’re becoming your family’s resident expert on the low-FODMAP diet. Of course you are! You’re the one on the plan, and you need to know the ins and outs of it, wherever you are—no matter how much your parents like to “helicopter” you. Even if they tend to take over when it comes to food, you are the one who will feel better after successfully staying on this plan. Taking ownership over some of the food shopping and prep can ensure that you actually stay on your Go Low plan long enough to reap the benefits.

The simple act of getting food from the farm, warehouse, or store to you is the first crucial step to eating according to the Go Low plan. If your kitchen pantry and refrigerator are packed with products you can eat and ingredients you can easily make, sticking with the plan will be that much easier. Even if you don’t typically buy groceries in your house, it’s a great idea for you to begin playing a bigger role in acquiring food for yourself and your family as you start phase one of the Go Low plan. Here are a few tips:

Get the app: Going low? Well, there’s an app for that, of course. As I mentioned earlier, the team at Monash University offers a smartphone app (iPhone and Android) that features a frequently updated database of the FODMAP content in foods, straight from their laboratory in Melbourne, Australia. A red-, yellow-, or green-light system makes it easy to decipher which foods you can eat. Almonds? Stop right there—that’s a red-light food; swap them for pecans and you’ll be just fine, however. Zucchini? Green light, go! The app is a bit pricier than most but is well worth the money.

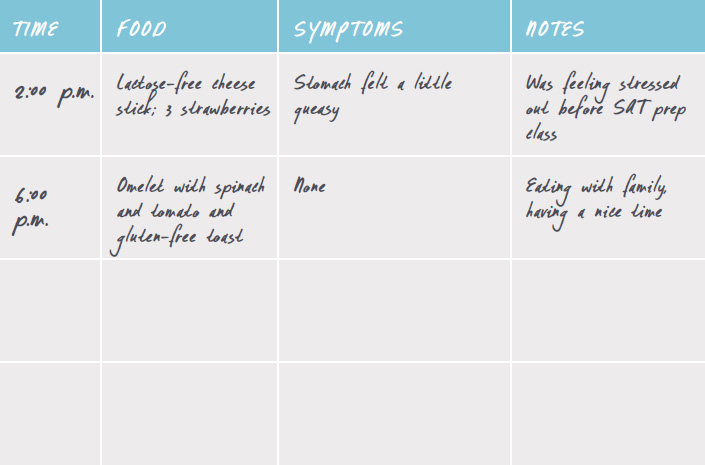

Use your journal to keep track of how you feel as you reintroduce No foods and any other relevant information you may uncover.

Brush up on your (label) reading: The most important—really the only important—thing you can look at to determine if a food is OK for you to eat is its ingredients label. While most packaged foods in the United States haven’t been analyzed for FODMAP content, you can still determine whether a food is likely to be safe by scouring the ingredients list. Not sure about something? Look it up on the Monash University app. To save you some trouble, take a look at the packaged-food ingredients list for some red flags.

Select a nutrition-minded store: Low-FODMAP ingredients and products are everywhere. But stores that have a good selection of gluten-free, Paleo, and other health-focused foods may give you a wider array of options. You still have to read labels (see Gluten-Free Does Not Equal Low FODMAP), but a store that makes an effort to stock items that fit into specialized diets can be a good place to start. You can also seek out conventional grocery chains that have an RDN on staff, like H-E-B, Safeway, ShopRite, Kroger, Giant Eagle, Bashas’, and Hy-Vee. The reason? These health-and-nutrition-focused professionals are trained in special diets; RDNs who work in grocery stores are pros at helping people track down the right foods for them. You can knock on their window and ask for some help—think of them like your own in-store personal shoppers!

Go Low online: I love online grocery shopping for two reasons: One, timing becomes a nonissue. In other words, if your dad does the weekly grocery run while you’re at volleyball practice, you can still participate. Two, you can take your time looking at ingredients lists and figuring out the foods that will work best for you. And three, you can do it all from the same device you just binge watched Empire on—all while sending your BFF snaps of you as a dog. Online grocery options vary by region; however, services like Thrive Market (thrivemarket.com) and AmazonFresh (fresh.amazon.com) are available around the country and give you access to a lot of great foods.

Maybe you’re not much of a chef—yet. But now is as good a time as any to acquire some culinary skills or at least help your parents out enough to start getting a feel for things. Bonus: Being confident and skilled in the kitchen will enable you to be healthier for life (also it’s a great way to save money and make friends—who doesn’t love a delicious home-cooked meal?!).

Whet your appetite: Being a cooking enthusiast is a great first step to getting comfortable in the kitchen. Watch the Food Network, Top Chef, or YouTube channels like Tasty. Read food magazines and blogs. You’ll be surprised by how much you learn and inspired by just watching.

Sign up for a cooking class: If your school offers classes that take place in a kitchen, take one. If not—or your schedule is already too packed—look into taking a class or two in your free time. Local schools in your area may offer cooking classes just for teens; culinary-supply chain stores like Sur La Table and Williams-Sonoma also offer specialized courses in some locations. You may also want to Google “low-FODMAP cooking class” and your hometown or closest city—more and more RDNs and chefs are offering low-FODMAP cooking classes; if you’re lucky enough to find one, I recommend participating with a parent so you can both learn and explore low-FODMAP foods at the same time and make it a fun expedition to go on together.

Make a meal plan: If you’re not quite ready to whip up dinner for your whole family, that’s OK. Start by scribbling down some notes. What Go Low–approved breakfasts do you think you might want each day? And which Go Low dinners would your whole family eat? Put together a list and share it with the person in your family who does the cooking; helping make decisions about what the people in your house will eat is a great first step to owning the kitchen.

Play the role of sous chef: In a professional kitchen, the sous chef is the second-in-command. Ask the head chef in your home, whether it’s Mom, Dad, or someone else, if you can play the role of assistant for the day; this will help you get your feet wet and gain proficiency in the kitchen before taking the reins yourself.

Do it yourself: Cooking is kind of like learning a foreign language. You can learn a lot from studying and watching other people hone their skills. But you won’t master it until you start putting the knowledge you’ve gained into practice. Ask the person in charge of your family’s kitchen if you can plan and prepare one meal. Choose something simple so your first effort goes as smoothly as possible. If that goes well, see if you can make it a regular occurrence. You’re not a kid, of course, but you might be down with a campaign called Kids Cook Monday, which inspires families to get young people in the kitchen one day a week. Check out thekidscookmonday.org for ideas on easy ways to get started.

Thinking ahead is also crucial to your Go Low success. If you’re always scrambling at the last minute to figure out what to eat, you’re more likely to grab the wrong thing in a hurry. Instead, make like a Boy Scout and “be prepared.” Here are a few ways you can do just that, supported by the great groceries you picked up.

Set yourself up with grab-and-go breakfasts: Ah, breakfast. It’s the most important meal of the day (so says your mom—and loads of nutrition experts, it turns out) and, somehow, the hardest to make time for. Think ahead about what you might eat for your morning meal—Go Low–approved smoothies, cereals, yogurts, and egg-based dishes can all be great choices (see breakfast recipes). However, they’re not always conducive to those mornings when you just need to get going. So be prepared (and practical) with foods you can eat on the run. See Breakfasts on the Run for some ideas.

Stock up on snacks: How many times a day do you eat a snack? If you grab a nosh more times a day than you pause for a meal, you’re not alone—American teenagers now eat an average of almost four snacks per day, according to research firm NPD Group. And because many of the foods we may reach for when it’s snack time, such as pretzels, energy bars, apples, and cookies, are not typically Go Low approved, snack time can be an extra challenge. Make sure to keep Go Low snacks like gluten-free pretzels or popcorn on hand. (For more ideas see Go Low Snacks.)

Have backup meals ready to go: It’s great if you can cook for your family. And it’s equally wonderful if your parents are on board and willing to make the Go Low–approved meals for everyone. But being prepared means that you have to be ready for whatever comes your way. And that includes those nights when everyone’s running late and Mom wants to order a pizza, or it’s your sister’s birthday and all she wants is her most favorite meal of honey-cashew chicken with cauliflower in garlic sauce (in other words, no, no, no, and no—sigh).

Cafeteria food can be underwhelming enough to begin with. Throw in some dietary restrictions, and it’s not surprising if you’d rather swap in advanced calculus for your lunch period. But it doesn’t have to be this way! And it won’t, once we’re finished here.

I need you to promise you will remember these three words: You require fuel. With the average start time for public high schools in the United States clocking in at roughly 8:00 am (meaning many are even earlier), by the time lunchtime rolls around it’s likely been a good four, five, maybe even six hours since you last put food in your body. As you’ll read in the next chapter, you never want to go more than four or five hours without eating, because doing so can lead to an energy slump that you don’t need when you’re trying to memorize the quadratic formula. Food = fuel. And by lunch period, you’ll need some.

The second reason lunch is so important is that your brain needs a break. We live in a fast-paced world where many of us have fallen out of the habit of stopping during the day to relax for a few minutes (I’ll take the blame for this on behalf of adults, because we were the ones who started this ridiculous trend). If you’ve ever spent your lunch period shoving a sandwich in your mouth while you finish some homework, you know that failing to take a break can make your day feel long and tiresome—and while it might prevent you from getting a zero for not turning your homework in, it can make the rest of the day kind of a bust. And as we discussed earlier, being stressed can worsen digestive symptoms. It’s true: Having a little time to hang out with friends to laugh and relax may actually be therapy for your stomach. So shying away from lunch period—for nutritional and scheduling reasons—is a big no-no.

Sadly, it can be hard to know what you’re getting when you buy food at the caf. Prepared foods can have ingredients that you wouldn’t expect. Plain-seeming rice, for instance, might be cooked in chicken broth that contains onions. Sautéed vegetables very well might have garlic in them. What’s more, most school cafeterias these days don’t make their food from scratch—in other words, food comes to them preprepared from a factory or commissary kitchen (a main facility where all of the cooking is done before it’s sent out to your school). The servers at your school might not even know what’s in the foods they’re plopping onto plates!

So what’s the lesson here? Well, simple. If you want to eat in a cafeteria and stick with a low-FODMAP plan, it’s crucial that you ask questions and get answers. You might not always get the answers you need—but you won’t know until you try. In the end, your ability to Go Low in your school cafeteria will really depend on the cafeteria itself, including how food is prepared and how much information the people who work there can give you.

To get to the bottom of what’s in the foods at your cafeteria, your best bet is to track down the person who holds this crucial information. Here’s a simple three-step strategy you can use to get the information you need:

1. Arrive in the cafeteria and scope out what you think some good options might be, thinking about what you want to ask about.

2. Speak with a friendly server or other caf staffer. Explain to her that you have some food sensitivities and you need to find out what’s in some of the foods to know what’s safe for you to eat. Chances are, she’ll direct you to the chef or the food-service director, who can better address your concerns.

3. Say hello to your friendly (I hope!) food-service director, chef, or other knowledgeable person! Not sure what to say? Of course not—it can be tough to speak up for yourself, especially when it comes to something complicated like going low FODMAP. Here’s a sample script of what you can say: “Hi, I’m on a special diet recommended by my registered dietitian and/or doctor called low-FODMAP because I have a sensitivity to certain types of carbohydrates found in different foods. The list of ingredients I can’t eat is long, and it’s not always easy to tell if prepared foods contain them—so I need your help to figure out what I can eat because you’re the one who knows what’s in the food here. For example, I can’t eat anything with wheat, onions, or garlic in it—even garlic or onion powder. The more simply something is prepared, the better. I noticed chicken, rice, and sautéed zucchini are being served today. That would be perfect for me, as long as they weren’t made with any ingredients on my ‘do not eat’ list. Can you possibly tell me all of the ingredients that were used?”

Your surest bet when eating at the school caf is bringing lunch from home. The main reason, of course, is that you get to control what goes into it and can make it both Go Low–approved and delicious. But there are some other major advantages. High school students who bring lunch from home are more likely to eat nutritious foods over the course of the day, according to a study published in the American Journal of Health Promotion (same for eating breakfast and having dinner as a family, for the record). Depending on what you typically bring from home, you might be able to pack the same lunch with a little tweaking to make it low FODMAP (like swapping your normal bread for a Go Low–approved one). Among the recipes in the back of the book, you will find a number of lunch options that work well on the go; find more toss-in-your-bag school-ready options above.

If you’re in college, the challenges of Going Low are similar to those of someone eating in a high school cafeteria times three, because you might be eating all of your meals in the dining hall—a social experiment designed by adults to turn kids into people who really, really want to cook for themselves (anything is better than Sunday Surprise!). Plus, you likely don’t have a full kitchen in which to make homemade meals to supplement the dining hall food. If this sounds like you, you might want to consider holding off trying Go Low phase one until you’re home from school on winter break or for the summer, so you can have slightly more control over what you’re eating.

If you’re really ready to go and can’t wait any longer, it can be done, no doubt—but it will take a little effort and resilience on your part (of course, that’s true any time you undertake a low-FODMAP plan). Go you, perseverant person, for accepting the challenge!

Hopping on the Low-FODMAP Express while you’re living at school means communication is even more important. Get on a first-name basis with the person who runs the show in your cafeteria—the food-service director, chef, or someone else—to find out what meals are truly safe for you. And don’t hesitate to give your input or ask for things you don’t see. Maybe they can start to keep some unsweetened almond milk on hand if they don’t already—undoubtedly the many lactose-intolerant and vegan students would be thrilled to see it, too.

First, do a little research on what foods your school’s dining hall does have. Google the name of your school and the phrase “food service” or “dining services.” You’ll most likely pull up a page that tells you what’s on the menu each day at each dining hall and restaurant your school has. If you’re lucky, the people who put food in your cafeteria will tell you the ingredients in the foods they serve. Which is pretty dang cool, because otherwise you might never know that the roasted red potatoes at Oregon State’s Southside Station at Arnold are made with onion and garlic powder, just like the grilled chicken found in Harvard’s salad bars. But you’ll also be able to uncover the foods that suit your Go Low plan just fine, even if meals may wind up feeling a bit random and cobbled together. If your school doesn’t list ingredients, you may be able to find contact information for a registered dietitian nutritionist who works with the school or the food-service company that provides food to your school. A friendly email to this person (refer to the script I gave you on here for how to talk to a caf worker in person) can help you get to the bottom of things and assist you in finding a few go-to meals you can rely on.