NEW MAPS FOR THE NEW WORLD

Maps are expressions of political power, both perceived and claimed. When the Romans set out to organize their expanding empire, they mapped the great lengths of roads and aqueducts that structured their social world. British cartographers provided merchants with maps of the best trading routes and equipped military officers with maps that identified the best places for fortifications. In recent years, we’ve started producing new kinds of digital maps that reveal new kinds of power. What new maps do we need to understand the new world order?

The usual map of the world reveals a patchwork of countries. Yet there is a surprising number of people and places that aren’t really connected to the countries they are supposed to be part of. We are used to political maps that mislead us about how governments are really able to govern. Many breakaway republics, rebel zones, and anarchic territories are connected with one another in surprising ways, through dirty networks that link drug lords with rogue generals and holy thugs. Dictators are major nodes in the dirty networks of crime, money laundering, and human trafficking that are often found in the world’s authoritarian regimes. Fortunately, there is a kind of demographic and digital transition taking place. The toughest dictators are getting older, while the average age of people they rule is dropping.

Social media, big data, and the internet of things are helping people bring some stability to even these anarchic places. Our crowd-sourced maps of social problems, produced by many people using many kinds of devices, help people find solutions. Increasingly the internet of things is structuring our political lives, and we can already see how people use device networks to create new maps that link civic groups with one another and with people in need. This internet can make people aware of their behaviors and relationships. It allows people to trade stories of political success and failure, and to build and maintain their own networks of family and friends. Sometimes, these networks evolve into powerful political movements. People use social media to make new maps and new movements, and to construct new institutions for themselves. Moreover, the internet of things is growing into a world where networks of dictators are calcifying, young people are using digital media to develop political identities on their own, and communities are involving information infrastructure in digital networks.

Crisis is an important catalyst for the creative and civic uses of digital networks. On January 12, 2010, an earthquake devastated Haiti. The epicenter was just outside Port-au-Prince, the capital. Homes collapsed and the National Assembly building fell into a heap of rubble. Years of deforestation had left exposed soil on many hillsides, so mudslides engulfed whole neighborhoods. The power was knocked out and telephone lines went down. The earthquake had a Richter magnitude of 7.0, and over the next few days there were some fifty-two aftershocks with devastating consequences. The headquarters of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti also collapsed, killing many, including the mission’s chief.1

Haiti is one of the most beautiful yet impoverished countries in the world. Natural disasters take a serious toll because recovery operations are so difficult. When I was working there in the mid-1990s, the urban slums of Port-au-Prince were home to at least 100,000 people. High walls often surrounded slums like Cité Soleil and Jalouse, which held people living in extreme poverty. It was difficult to assist people in these districts, because aid groups had trouble figuring out who needed what help. Haitian Creole is a relative of French, but even if you learn the language, it can be difficult to earn the trust of the people you want to help. A few months after I left, Hurricane George devastated several large districts. The slums near the ocean flooded, causing hundreds of deaths and displacing almost 200,000 people. Recovery operations were painfully slow.

When the earthquake struck in 2010, the devastation was not only overwhelming but overwhelmingly difficult to recover from. U.N. agencies scrambled for information about what was going on. Relief workers reported from particular settlements, but didn’t know what was going on in other parts of the country. Satellite images revealed the parts of the coastline that had flooded, but could not assess the health and safety needs of people on the ground. Which collapsed buildings had entrapped people? Where were people congregating for help?

Within hours of the earthquake Patrick Meier, a student in Boston, formulated a plan to help.2 Desperate pleas for assistance were coming over the television news and his own social networks. Eager offers of help were also coming over Twitter, so why not crowd-source the problem and map out the situation? He turned his small Boston living room into a “situation room,” where volunteers took queries from emergency response personnel working sixteen hundred miles away in Haiti. Fueled by coffee and working on laptops, the team wrote software for a basic crisis map that would show anyone with an internet connection both the need for and the supply of aid.

The map quickly became the centerpiece of collective action. Within a few weeks, the international community was depending on the amateur crisis map to coordinate its efforts. The application helped to rationalize efforts. It served more than an organizational function—it served an institutional function. In Haiti, the government lacked authority and organizational capacity. But for a brief period during a desperate crisis, the crowd-sourced map provided something of both.

An “organization” can be usefully defined as a social unit made up of people and material resources, like desks and telephones, while an “institution” consists of norms, rules, and patterns of behavior.3 The map became both an organization and an institution. The digital crisis map provided an immediate logistical tool for coordinating relief workers. It helped to establish the norm that social problems could be tackled by wide-ranging, territorially dispersed volunteers interested in behaving altruistically. Social media made it possible. People put in their energy. Device networks of mobile phones and mapping software provided structure.

When I was in Haiti in 1997, it took an extensive search to find recent maps of Port-au-Prince. The United States had made some maps twenty years earlier, but there was nothing more recent in the Haitian National Library. The Ministry of Development didn’t have them, and there were none at the main university. After several weeks of searching, I found the best maps in the U.N. compound. They were under lock and key because administrators didn’t want the maps to get into the hands of corrupt officials, drug smugglers, and human traffickers.

Despite the best efforts of the United Nations, even these maps inaccurately charted the capital’s slums. And I was allowed to make photocopies only because the security guards liked my Canadian bona fides. Mapping social problems is certainly not a new idea. The possibilities have grown with satellite images, hobbyist drones, cloud storage, expanding device networks, and the altruism of the crowd. Since 2010, dozens of poor communities have started building new organizations and institutions through mapping and device networks. Like the slums of Haiti, the slums of Nigeria are also difficult for the government to see and serve.

Digital networks can expose connections that political boundaries do not. Two-thirds of the world’s population lives in countries without fully functional governments. Or more accurately, they live in communities not served by states with real governments. They live in refugee camps, breakaway republics, corporate-run free economic zones, gated communities, failed states, autonomous regions, rebel enclaves, or walled slums. Modern pirates dominate their fishing waters, and complex humanitarian disasters disrupt local institutions regularly. Organizing people to solve problems in such places is especially tough.

In many of these places, rogue generals, drug lords, or religious thugs who report to no one (not on this earth, anyway) lead governments. Not having a recognizable government makes it tough to collaborate with neighbors on solving shared problems. These liminal states tend to support alternative dirty networks of criminal leaders, human traffickers, and local despots.

These places have been growing in number, population, and territory. Criminal gangs, religious fundamentalists, and paramilitary groups that disrupt global peace thrive in these places. Yet these places are not always chaotic. In recent years, these locations—and there are many of them—have actually started showing that government is not the only source of governance. Information technologies have started to fill in for bad governments and become a substitute venue for public deliberation.

While population growth is making these unstable parts of the world younger, many of the world’s dictators are only getting older. These days, the vast majority of the worst dictators are older than seventy or have serious health problems and no clear succession plans. Some of them control only tiny countries with few resources, but all are nodes in a network that support the growing global reach of the criminal gangs, religious fundamentalists, and paramilitary groups in their countries.

Most of them came to power before the turn of the twenty-first century. As dictators, they faced and still face a digital dilemma—a difficult choice over whether to allow their citizens access to the internet. If they do not allow internet access, the population misses out on the economic opportunities; if they allow internet access, the population gets access to news and information from countries where people live more freely. As aging dictators, they already encounter more and more open challenges to their rule from rivals and democracy advocates; internet access can only exacerbate this challenge.

What’s the connection between aging dictators, malformed governments, and the internet? As the internet and mobile phones arrived in many corners of the world, people began to realize that they could make connections that their government couldn’t or wouldn’t make. They started communicating with their neighbors. Young people who had never known a political alternative to authoritarianism started exploring their options. People began using social media to turn political problems into opportunities. The internet and mobile phones provided a new structure for political life.

In the late 1990s, the global information economy was booming. Egypt was also doing well, at least compared with some of her neighbors, but was coming under pressure to modernize. Since so much economic growth seemed to be tied to the internet, Egypt’s strongman, Hosni Mubarak, faced a dilemma.

Giving the country’s major businesses access to fast telecommunications services seemed like a good economic strategy. Cairo is an important financial center in the region, and many of the country’s state-owned businesses would benefit from a strong communications infrastructure. Fast internet links to Europe and North America could inspire innovation and entrepreneurship at home. It would also make Mubarak look like a forward-thinking, modern leader. If the internet was good for the economy and a booming economy could help keep Mubarak in power, it made sense to invest in the internet.

At the same time, the internet also seemed like a chaotic place. There was news and information from other countries. There were reports flowing in from Egyptians abroad, not all of whom supported Mubarak’s rule. Censoring the internet might cancel out the economic benefits, discouraging entrepreneurial creativity. Were the political risks worth the economic opportunities?

Mubarak and his advisers decided to go all in. They privatized the national phone company and in 1998 gave it a new name—Egypt Telecom. The company that had brought the first telegraph line to Alexandria in 1854 was now going to bring the internet to all Egyptians. It expanded its data services and invested in a mobile-phone operator.

The government tasked the Ministry of Communications and Culture with encouraging internet use around the country. It initiated a public-private partnership with Microsoft that involved lowering the cost of buying legal software to Cairo residents who could demonstrate that they were responsibly paying their utility bills. Schools and libraries got internet terminals. New fiber-optic cables were laid. The price of making cell phone calls dropped quickly. For practical reasons, Cairo was the main beneficiary of all this. Egypt has modest income inequalities, but the fastest technologies went to wealthy urban elites of Cairo and Alexandria. Most of the infrastructure investment went to those cities, and not every Egyptian could afford to get online anyway. People around the country found mobile-phone services a great new way of connecting to family and friends.

In 1998, the Lonely Planet Guide for Cairo listed the cheapest internet cafés and gave prices at around two U.S. dollars for an hour of access. This meant that internet use was really only for tourists and the wealthy, because the average income for people working in Cairo was around nine dollars a day. Ten years later, access was pennies an hour. And cybercafés were thriving mostly in the poorer districts of Cairo, because many in Egypt’s growing middle class had access through home and work. A dilemma is a problem with two possible, equally undesirable, outcomes. Mubarak’s choice to provide connectivity for citizens had political consequences.

Eman Abdelrahman carries herself with a humble and quiet demeanor. She founded, then led, a community of young women who were at the center of Egypt’s popular uprising. As a young Egyptian, she grew up only knowing Hosni Mubarak as president. She was not known as a rabble-rouser, and did not consider herself a feminist.

But in the summer of 2006, she was tired of being a second-class citizen. She and her friends were feeling less and less connected to political life in the country. Or more accurately, they were using the internet to learn about life in countries where freedom and faith coexist, and they were having political conversations through blogs and Facebook.

One day in August of that year, she was chatting with one of her friends online, and they found themselves complaining about the way men treated women in their society. As young women, they faced limited career options and sexual harassment on the streets. Without much planning, they decided to blog about their frustrations and share ideas about what could be done about their grievances. It took only a few hours to find three other female bloggers who were eager to write together. They had a group chat that night. What should they call themselves? Would they campaign for something specific, or were their goals more broadly about community building?

They all had a favorite book, Latifa el-Zayat’s The Open Door.4 In this book, the protagonist, Laila, is a young Egyptian girl who faces daily situations in which the men in her life always seem to get the upper hand. Egyptian society prevents young Laila from achieving her goals, even as she tries to have a political role in the country’s nationalist movement. But she continues to believe in the importance of her role as a woman, and she continues to have faith that change will come. Abdelrahman and her friends settled on the blog name: Kolena Laila, We are all Laila.

Some pundits, including Malcolm Gladwell, argue that digital activism is inherently less productive than face-to-face mobilizing. When I met Abdelrahman a year after the Arab Spring, I asked her about the lasting impact of her virtual writers’ group. She said that they had put into practice a key aspect of Egyptian political life that had been missing for a long time. They introduced—or reintroduced—the idea of writing together, publicly. Mubarak’s decision to support wider internet access was especially significant for Abdelrahman and her friends. That summer of 2006 they found fifty other female bloggers willing to write short essays about their experiences as young women in Egypt. Some wrote about the daily burden of sexual harassment in the streets. Others posted opinions about female genital mutilation. Their strategy was to all write posts on the same day, referencing Laila. This way, the Arabic blogosphere would be awash with gender politics. In a coordinated effort, Abdelrahman and her friends were able to generate content, and spread that content around the Egyptian blogosphere.

Each year, the project had a bigger and bigger impact. More young women bloggers wanted to contribute, and each year they had more readers. They also had some difficulties along the way. Some male bloggers wrote in support of the group’s efforts, while others disparaged it. Not all of the core writers had a steady income, and as a group they had trouble funding their collective work. They were accused of being an anti-Islamic feminist movement. They probably weren’t that, but they probably were digital activists. They were an organized public effort with clear grievances who targeted authority figures and initiated campaigns using device networks.

The group managed to coordinate contributors for four years.5 Members still savor a particular victory, in which they successfully campaigned to pressure a father in Saudi Arabia to allow his daughter to return to Egypt because she wanted to pursue academic studies. Eventually, the day of coordinated blogging became a week of collective writing and conversation. The mainstream media covered the group’s activities. In its final year, Kolena Laila attracted two hundred female bloggers, from thirteen countries around the region. Despite victories like this, the group’s founders still admit that cultural change is slow.

But the group’s larger contribution to Egypt—and the region—was to popularize a new meme in Egyptian civic engagement: “We are all.” Kolena Laila was among the first in Egypt to use digital media as a way of raising shared grievances and getting people to realize that their troubles were not theirs exclusively. Sociologists call this “cognitive liberation.” People start to realize that they’re not alone in wanting to improve their lives, and that they share strategies for doing so with their neighbors.6 The internet can help cognitive liberation come more quickly.

That’s because what keeps dictators and ideologues in control is their ability to make people think that they are alone in their opposition. Pluralistic ignorance—when people publicly accept an injustice but privately reject it and aren’t aware that others reject it too—is a lot harder when digital networks provide constant ambient contact with others. Authoritarian governments work to make citizens believe they will be all alone if they show up for a protest.

Soon after Kolena Laila started, other internet-based organizations picked up on the phrase “We are all” for their digital campaigns. When a young man named Khaled Said was beaten up and murdered by corrupt police officers in the streets of Alexandria in the summer of 2010, a movement arose to document the attack. Photos of his brutalized body lying in the morgue circulated online. People joined the group in solidarity, realizing that their personal experiences with corrupt security services were actually a shared experience.

The number of people who supported the group grew immensely, and its organizers decided that it was time to take to the streets. They learned from the success of Eman Abdelrahman and her friends in raising public awareness. Kolena Laila had popularized the notion that you could use the internet to share your political grievances and aspirations. The group memorializing Said took to the internet. Members took their cue from the successful Laila movement, calling themselves “We are all Khaled Said.” In January 2011, they brought the Arab Spring to Egypt.

There have always been bad governments. For much of the twentieth century, most of the world has had one of two types—the kind that was not good at governing or the kind that was only pretending to govern. When the Soviet Union collapsed, many countries in eastern Europe and central Asia descended into chaos and corruption.

Fewer than two hundred “real” countries have governments and political chiefs who recognize one another in U.N. bodies, international financial organizations, and the like. Even the vast majority of those governments function only in some parts of the countries they represent, and some political leaders don’t travel far out of their capital cities for safety reasons. Somalia is but one example of such a country: its government controls a few blocks in Mogadishu, and only with significant help from neighboring nations.

We call these weak, failing, or failed states, and many people recognize that these weak states are a threat to global peace. Most of the governments in these states aren’t disruptive, and they rarely have the capacity to threaten their neighbors. They are corrupt and treat their people poorly. Usually, it is criminal organizations that grow up in place of governments—within national borders, or within corrupt bureaucracies—that disrupt global politics. Often criminal organizations operate in parallel with states. Sometimes zones of a state are controlled by local rebels fighting for self-determination.

For example, there are de facto autonomous zones in the Kurdish areas of Turkey and Syria. The Turkish military regularly conducts “raids” within its own borders. The Gorno-Badakhshan region of Tajikistan is another such place, where an ad hoc alliance of Russian military, government officials, and local Pamiri power brokers manage the shipping of a third of all the opium coming out of Afghanistan.

Then there’s the northern district of Mali, with Timbuktu, the regional capital, managed by Tuareg rebels and jihadist groups. The Ansar Eddine, a militant Islamist group, managed to cut a deal with a more secular independence movement to chase Mali’s army out of the northern part of the country. The rebel groups are factious and hardly law abiding, but they manage an area the size of France and have little to fear from the struggling Mali government. Boko Haram, a similar group, is trying to isolate a whole region of northern Nigeria from Western contact. When it kidnapped hundreds of girls, no local authority was able to recover the victims or dispense justice. The kidnapping inspired a global campaign, Bring Back Our Girls, that drew as much attention to the region as the Kony 2012 media campaign had.7 That campaign involved a viral video documentary that reached half of the young adult population in the United States in a matter of days.8 The activists involved sought to have Joseph Kony, the leader of an armed gang in Uganda, arrested for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Significant areas of Pakistan are difficult for the country’s security services even to enter. North Waziristan, the Punjab, Kashmir, and the federally administered tribal areas are barely governable. In the Philippines, the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao is made up of communities that have voted for a degree of self-rule.

In Peru, the Shining Path was defeated long ago, its leaders jailed or killed and its members pushed far back into the jungle. It still operates within the regions of Apurimac, Ene, and Mantaro, providing security for local drug lords. Some 40 percent of Guatemalan territory is outside the control of the state. Pirates seem to rule the waters off Somalia and throughout the island archipelagos of Indonesia. The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) openly uses device networks to coordinate its communications from hubs in multiple countries. Indeed, these kinds of places are not exactly ungoverned; they are managed by organizations other than governments. The groups that manage these areas sometimes have the power to destabilize their neighbors.

Such spots are the first to fall apart during a political or military crisis. When pushed, central government leaders have to admit they have no control. They focus state resources on the capital cities they inhabit and the areas with national resources that generate wealth. For example, when Syrian rebels started scoring some real victories, Assad gave up his Kurdish region almost immediately, opening a vacuum for the brutal terrorist group ISIS to fill.

The list of limited, failing, or failed states is long. Some governments aren’t functioning well, but that suits ruling elites just fine. Governments can be built to fail. Ruling elites extract the resources from the country and know full well that the government won’t act against them. The father-son dictators François “Papa Doc” and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier ruled Haiti for a long time as dictators, and did not leave behind a government able to collect and spend taxes, protect property or human rights, or provide for collective welfare.

Not all governments fail entirely, but even having part of a government fail causes problems. When the head of a particular state agency is siphoning off an entire ministry’s income to private accounts, the agency won’t be able to deliver governance goods. When governments become deeply entwined with criminal organizations, the failure becomes, in a sense, coordinated. It takes only a few corrupt officials to prevent military, police, and justice officials from doing their investigative work. Keeping the state failed becomes an essential service for the criminal enterprise.

Unfortunately, such partially failed governments do provide some public good—often just enough to prevent outright rebellion and keep the criminal enterprise going. That’s why drug lords sometimes build roads and keep petty crime in their region under control. They won’t allow an environment of competition, so power grabs in other ministries or moves by rival drug lords are always tracked. And there are examples of significant armed forces that provide “governance goods” in the sectors they control: the Tamil Tigers, the IRA in Northern Ireland, and the Kosovo Liberation Army often functioned like the states they were fighting by running local courts and hospitals, and dispensing different kinds of welfare.

The big tragedy is that all these different kinds of places are crowded with people. Almost by definition, slums are among the worst places to live, and about a billion people live in slums.9 In the years since I was in Haiti, Cité Soleil has grown to at least half a million impoverished souls. Slums are places where water and electricity supplies are meager and economic opportunities are few. Because slums rarely have any political clout, their uncertain status exacerbates residents’ challenges. Health services are paltry, and food supplies inadequate. It’s not always clear who governs, and even when it is clear, it is rare to find a selfless slumlord.

Mukuru kwa Reuben, for example, began as a labor camp outside of Nairobi, Kenya. It has been around for many decades: now home to well over a hundred thousand people. Politicians have little authority there, and there are no clear property rights for its residents. Rumors of eviction often motivate people, and the outcome can be violent. Not far away, ninety million live in Nigeria’s north, a region terrorized by Boko Haram. Almost every country in the Global South has such areas. Some would say that people there live under siege, others that they have the governments they want and deserve. In 2013, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that there were more than fifty-one million refugees living in camps around the world—the most ever.10 In these liminal states of countries with lousy governments, big data, social media, and the internet of things can have a big impact.

The Dictator’s Digital Dilemma

Ruling elites have faced the digital dilemma in many parts of the world, and most are still wrestling with the consequences of their choices. As governments are presented with the option—or need—to regulate the internet of things, they will have to evaluate economic benefits and political risks. I visited Baku, Azerbaijan, in 2004 and met with several activist bloggers. They would speak to me only on the condition of anonymity. Every few months, they would organize a smart mob. At an agreed time, young people would gather in the city’s Central Park and open up newspapers. They would sit on park benches around fountains and in circles on the pavement. Then with their newspapers open, they would kick off their shoes all at the same time. The police would come by and get angry with the students. One or two would have to spend a night in jail. The police never knew how to handle such events and never had a coordinated response. Were these events even protests?

When I spent time with these bloggers, they complained that few of their events ever seemed to have much impact on public policy in Azerbaijan. So I asked them why they did it. “These protests are not about toppling the regime,” one activist replied after some deliberation. “They are about teaching the regime that the internet now makes collective action possible.”

In Minsk, Belarus, protests happen in a similar way. It’s not always clear that the protests are, in fact, protests. Belarus’s security services are often unsure about how to react. Yakub Kolas Square normally contains skateboarders, promenading couples, and grandmothers herding grandchildren. But on particular days, chosen by some mysterious process of consensus, the square fills to capacity. The park benches are suddenly all occupied. People perch on curbs. Howard Rheingold famously called these gatherings “smart mobs.”11 And at 8 P.M., a chorus of mobile phones goes off: chirps, chimes, and pop music come together to make a cacophony of absurd ringtones.

The police are there, because they too can read the website where instructions for how to pull off this smart mob are posted. Who should be arrested? Can someone be arrested for having her mobile phone go off? More important, is it still a protest if you can’t tell who is protesting or why?

Regime response varies, because the digital dilemma is complex. Some people get a few days of jail time for participating in these kinds of protests. Some people get years. Sometimes the police have to make up laws, because it is difficult to prosecute someone simply for having a ringing phone.

Such protests have mobilized large numbers and pose real threats to ruling elites. They attract young people and draw them into protests. Protesters don’t always use the methods of past generations: picketing, marching, and chanting. In fact, research shows that digital activism, when it leads to street protests, is usually nonviolent.12

Strange protests like the one I attended don’t happen just in Azerbaijan. They aren’t all as abstract as the ones in Minsk.13 They happen in Havana. In the final days of Burma’s military junta, they happened there, too. What is common is a rising level of innovation in protest strategy. Russia’s Pussy Riot does aggressive culture jamming. In Ukraine, the Femen network of young women bare their breasts in public but then talk about pension reform. The Russian art collective Voina painted a two hundred–foot penis on a Saint Petersburg drawbridge to protest heightened security. Ukrainian activists launched a Kickstarter campaign to buy themselves a “people’s drone” that would let them watch Russian troop movements in their country.14

The internet of things is putting tough regimes into digital dilemmas on a regular basis, because leaders have to choose between two equally distasteful actions. Should they keep the internet on for the sake of the economy? Letting people have mobile phones runs the risk that they will coordinate themselves in some way to talk politics rather than business. Or should device networks be greatly restricted, to preserve political power? So the dilemma persists. Mubarak faced it at the end of the 1990s, but today’s aging dictators face it regularly.

For many authoritarian governments, their first digital dilemma was presented twenty years ago. They had to choose between building a communication infrastructure that might connect their national economies to the global information economy, or staying largely offline. As in Egypt’s case, being connected offered the potential for economic growth. What dictator would pass up the opportunity to appear modern and make more money for himself and his network of sycophants?

Countries like Malaysia, the Philippines, and Egypt chose this strategy and have faced the political consequences of encouraging widespread technology use. In other countries, such as Cuba and North Korea, ruling elites chose to eschew information technologies. A few countries maintain the social control sufficient to repurpose and reengineer their internet—or to populate their internet with supporters. Only one authoritarian government has the resources to make another choice: China has been building its own internet (more on that later).

The countries that chose to invest heavily in information infrastructure saw some economic benefits and did their best to mitigate the political risks. They hired Silicon Valley firms to develop censorship systems. They passed laws governing who could use the technologies and for what, and they clamped down hard on broadcast journalists. Most countries that chose not to build public-information infrastructure have changed their policies. Cuba has loosened restrictions on mobile-phone use, and the level of political conversation not policed by the state has increased. Myanmar has opened up. Making mobile phones more affordable has been a top priority for civic groups. Only North Korea has managed to keep device networks at bay, simply by not allowing them to be plugged in.

If you were a dictator, would you invest in good information infrastructure? If you don’t, you may watch your economy slow down and the world move on. Would you go after people doing creative political protests using digital media? If you don’t, you run the risk that symbolic gestures and obscure protest tactics will invigorate your opposition. Authoritarian regimes face the digital dilemma repeatedly: once when deciding whether or not to allow internet access, again when people (invariably) start involving their devices in politics, and yet again when citizens demand access to the latest televisions, phones, and other consumer electronics that constitute the internet of things.

The Map Kibera project in Nairobi, Kenya, is one example of how this process has helped a marginalized community figure out its strengths and understand its needs.15 This act of citizen mapping has made invisible communities visible. And it demonstrates how the internet of things is helping people bring stability to the most anarchic of places.

Primož Kovačič is a soft-spoken Slovenian who left his country in 2007 to work in Africa. He’s not sure why he chose to settle in Nairobi, much less in one of its toughest slums. Once there he found a community with immense amounts of economic, cultural, and social capital that had no strong institutions. Kibera is a place where hundreds of thousands of people live. For decades it has been politically invisible because no public map recognized the boundaries of the community, and leaders didn’t pay much attention to its needs. Some people call it Africa’s largest slum, while the people there call it home.

Estimates vary about how many people actually live there. Some estimate 170,000, others say upward of a million.16 Whatever the real number is, it is an enormous area and a blank spot on the map until 2009. In fact, many government maps still identify Kibera as a forest. Even Google Maps reveals few details for one of the most crowded and impoverished slums on the planet. By itself Nairobi has some two hundred slums, few of which are on government maps. Some poor districts of the world’s megacities, like Nairobi, become what Bob Neuwirth calls “marquee slums”: they attract all the big nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and charity projects.17 Most of them were not on maps, until Primož Kovačič arrived.

Kovačič decided to help launch a collective project to, at the very least, map the area.18 Gathering a group of volunteer “trackers” equipped with some basic consumer electronics, including cheap GPS devices and mobile phones, Kovačič and his colleagues “found” Kibera. They identified two hundred schools. They located thirty-five pharmacies. They charted hip bars with late-night dancing, and they found quiet corners where people go to die. They geotagged the sewers, most of which are open, and created layers of data. People from the community were involved in designing the online interface and doing the data collection. They interpreted the data themselves and came to four conclusions.

• They needed more toilets.

• Bad roads meant too many accidents.

• Children had no playgrounds.

• The sewer lines were broken.

Of course, the government saw Kabira as a forest. These new maps demonstrated that it is a community. The community was able to make its own maps for collective needs like clean water and sanitation. Power comes from designing information in a way that lets you act on it.

Focusing on priorities made it easier to act. Within only a few weeks, journalists were covering these problems, small groups of neighbors were working on specific issues, and politicians were alerted. Not only did Primož Kovačič help to find Kibera, but he also helped the community find itself. Social media lowered the cost of collaboration to a point where resource-constrained actors—like Kibera’s inhabitants—could agree to solve their problems.

Not everybody was happy about this, of course. Elders and district officers expected bribes. The police didn’t like having an organized way of tracking community life that was independent of their authority. Conflicts arose, especially at election time, when the cops claimed that crime was under control. Kovačič told me that the community could even generate their own maps now, showing that crimes were on the rise and demonstrating that police often committed these crimes.

One of the lessons of these mapping projects is that they never just produce maps. Social media make such maps organic, dependent on their contributors for life, and able to expose trends and problems that contributors don’t even anticipate. They now have great documentation of the scope of their problems. So Kovačič’s next project is to work on a system of finding people and resources to respond. They’ve clearly mapped the contours of the community and the needs of its people. The next challenge is linking the people in need to the people who can help.

Power comes from designing information in a way that lets others act on it. When I asked Kovačič about the impact of the project, he looked back at the digital map of Kibera. “The important outcome is not the dots on the map,” he said. “It’s about the social capital and ties that come because of the mapping and after the mapping.” In other words, the map was the project. But the volunteer network, civic awareness, and political literacy were the outcomes. Projects like this never really end; they evolve. Software gets repurposed. People build skills and take those skills to new projects. These projects go a long way toward helping people generate information about themselves, especially information that they need the most. In this way, digital media bypasses the state but also bypasses Western NGOs.

Slums that can organize themselves are a real threat to dictators. Fortunately, with a few notable exceptions, most of the world’s dictators are an aging bunch. This is understandable, because the absence of world wars has meant a prolonged stability that makes both democracies and dictatorships seem more durable. It may seem crass to speculate about state leaders’ life expectancies. Given the murderous history of some strongmen who might be on the list, it is not unreasonable to think through the means and implications of their departure, and make a dictators’ dead pool.19

For example, Saudi Arabia is a constitutional monarchy and an important ally for the West. In 2012, the Saudi Crown Prince Nayef al Saud died—not unexpected given his age and infirmities. He was the second crown prince to die in a year. The next crown prince, Salman al Saud, turns eighty in 2015, and the Saudi king, Abdullah, turned ninety in 2014. The family tree is complicated, but it is possible to imagine a line of succession. Plenty of authoritarian regimes have no leadership succession plan at all.

Making such a list may seem macabre. But to understand the challenges in international affairs in the next ten years requires thinking about the “predictable surprise” of the demise of these major nodes in the world’s dirty networks. Expect crises wherever there is an authoritarian regime with a sick or aging dictator, and ambiguous or nonexistent succession plans. And there are authoritarian regimes where the government has promised elections, and where young, tech-savvy voters will probably use social media to organize against the bald-faced lie of rigged votes. Table 1 identifies the ten toughest dictators who were more than seventy years old in 2015, according to political scientists of the Polity IV Project. Some of these characters have been around for decades, and there are others we could worry about. Among the countries that experts rate as being mildly authoritarian, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe is over ninety, Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bou teflika is approaching eighty, and Cuba’s functioning strongman, Raúl Castro, is over eighty.

Chaos invariably follows a strongman’s exit from office—even if he leaves through natural causes. Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez was in and out of Cuban hospitals during his third presidential term. In 2012 he successfully manipulated the media and electoral systems to guarantee a fourth win, but died barely three months into that term.20 An election was quickly held, but the country was plunged into a bitter rivalry between Chávez’s former vice president Nicolas Maduro and the opposition leader Henrique Radonski. Maduro won, but with just a tiny margin, and widespread protests flare regularly.

Table 1 Ten Most Authoritarian Leaders over 80 Years Old, 2015

This cohort of aging dictators is a major source of instability today. When and how they leave power has an enormous impact on the stability of the countries they rule and the regions in which they have influence. The death of an authoritarian ruler often brings chaos for his subjects and neighboring countries. Even while they are alive, these authoritarian rulers provide important nodes in the global network of criminals.

Even when dictators are young, they tend to generate another kind of problem for the world—they directly support aspiring criminals and other local despots. It’s in these failed and limited states that we tend to find pirates, drug lords, holy thugs, rogue generals, and many other kinds of miscreants. They are the key nodes in dirty networks. They represent the real threat to stability. Their networks are also surprisingly fragile when faced with a civic response.

These rulers can operate surprisingly close to home and within parts of the West. In parts of Mexico, drug cartels staff the police force and military with their own people. Indonesia’s province of West Papua is rich in oil and natural gas. Immense palm oil plantations have sprung up, pushing aside the rich jungles that have been felled for timber. Foreign journalists have trouble getting in, people have trouble getting their stories out, and the army helps to manage resource extraction for political elites that support the national government. The army basically manages the entire territory.

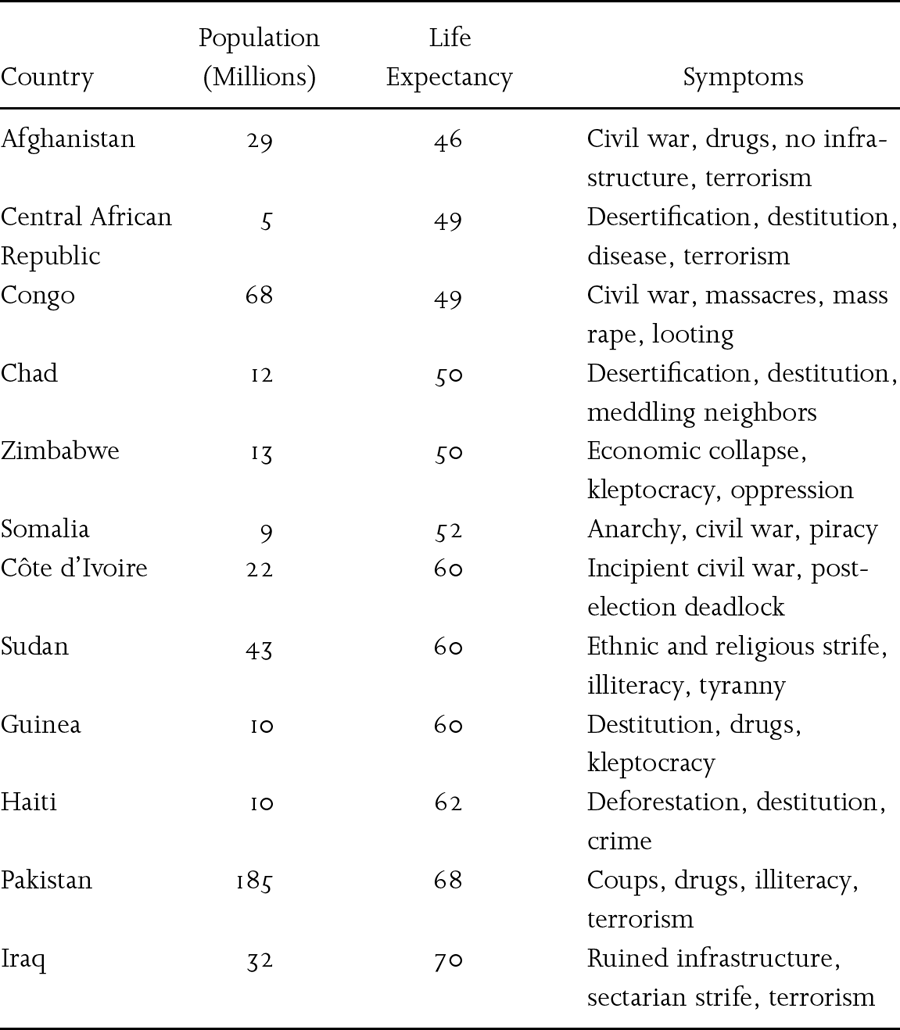

At any given time, the list of places where anarchy rules contains about a dozen countries. In Somalia, Chad, and Sudan, environmental degradation, ethnic and religious strife, illiteracy, and piracy prevent democratic and civic institutions from gaining much ground. In Zimbabwe, Congo, and Afghanistan, civil war, economic collapse, and kleptocratic governments prevent public organizations from doing much for the common good. Table 2 identifies some of the other places where governance is irregular and governments are incapable. The real challenge in international affairs has become the connection between these disparate places. Leaders in chaotic places sometimes provide hope to their populations. They are led by men who claim authority on the basis of spiritual leadership or military might. They manage small economic empires and they govern, in a fashion.

They govern, sometimes in similar ways to elected politicians in democracies. They collect taxes, dispense justice, and write the history textbooks.21 Sometimes they build bridges, maintain small armies, and work with civil-society groups. Sometimes the quality of life for average people living in controlled territories actually goes up—though the distribution of wealth tends to be through sycophants who support the ruling leader. The links between authoritarian regimes involve fuel, loans, and immigration (as well as drugs, smuggling, piracy, weapons sales, human trafficking, and money laundering).

Table 2 Anatomy of Chaos, by Life Expectancy, 2015

Source: “Where Life Is Cheap and Talk Is Loose,” Economist, March 17, 2011, accessed September 30, 2014, http://www.economist.com/node/18396240.

Afghanistan produces at least 80 percent of the world’s heroin, and the country’s intelligence services have an internal problem with heroin addiction.22 But in insurgent provinces, the Taliban is actually able to tax the drug lords because it commands key points in the networks of roads leading out of the region. For the drugs to pass, the smugglers need to tithe to the Taliban.23 Even where the truckers are carrying legal produce, corrupt police can exact some on-the-spot “fines.” In Indonesia’s province of Aceh, the traffic cops have complex pricing schemes for illegal payments: truckers pay different rates based on the type of cargo and the size of the trucking business.24

Sometimes it seems as if smugglers are behaving like governments, and at other times it seems as if governments and smugglers have simply merged operations. Criminal groups and government officials have long collaborated. Even democratic governments have had to collude with criminal gangs to smuggle guns to people fighting authoritarian regimes and to smuggle people out of those countries. Criminal gangs bribe and cajole government officials to turn a blind eye to their operations. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, it has been increasingly difficult for analysts even to tell the difference between criminal gangs and governments in some parts of the world.

These “mafia states” are well-blended organizations in which the highest government officials are also the leaders of criminal enterprises.25 Those officials dip into the public purse as needed for the defense of the enterprise. Indeed, they work to put official priorities and public policy in service of the enterprise. Bulgaria, Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro, Myanmar, Ukraine, and Venezuela are countries where crime watchers say organized crime and government are inextricably intertwined.26

Criminal groups have also started using the latest communication technologies, including software encryption, mobile phones, and the internet, to improve their operations and to find new sources of income. Cybercrime cost the global economy some $113 billion in 2012, according to a leading provider of internet security.27 This information infrastructure has allowed such a thorough binding between state and crime that the scale and scope of the problem are best thought of as a problem with national security implications and political solutions. Even strong states are increasingly thought to use their mafia connections as an arm of state power. The Russian mafia has been directed to supply arms to the Iranian military and Kurdish rebels in Turkey.28 The lesson is that, for some countries, foreign policy and criminal aspirations are indistinguishable.

Dirty networks connect extremely poor parts of the world, or connect the poorest communities of the rich world. The number of poor people in fragile states has remained fairly constant for almost twenty years—even considering the changing list of fragile states and the rapid population growth rates of poor communities.29 Yet their global distribution is changing. The number of poor people in fragile and conflict-affected states has just surpassed the number in stable states. Impoverished countries are not automatically the most fragile ones.

The very device networks that empower dirty networks also expose them to being mapped out. Individuals maintain mobile phones, often several phones in several countries, that allow for geolocation. They are global citizens, too. The Economist points out:

Examples include Somali warlords with deep ties to the diaspora and Western passports; Congolese militia leaders who market the products of tin and coal mines to end-users in China and Malaysia; Tamil rebels who used émigré links to practice credit-card fraud in Britain; or Hezbollah’s cigarette smuggling in the United States.30

Indeed, of the world’s dirty networks, ocean piracy may be the next to collapse. Somali piracy was costing the shipping industry and governments as much as $7 billion a year by 2011.31 With more than two hundred cases of successful hijackings per year in recent years, a network of naval task forces was established to deal with the problem. The European Union set up a flotilla; NATO provided another; and China, Japan, India, Iran, Russia, and Saudi Arabia coordinated a coalition of warships. These unlikely collaborators have been meeting four times a year to share tactics and intelligence. The Somali government helps, too—it wants to be rid of the pirates as much as any government. These days, Haradheere, the pirate haven, is reportedly devoid of Mercedes SUVs, prostitutes, and kingpins.

Failed states are great at incubating dirty networks. With dictators dying off and the data trail of bad behavior growing, the biggest dirty networks are on the brink of collapse. Under the noses of these aging dictators, and in places that aren’t states, you can find a surprising bloom of civil-society groups. These groups are using digital media in creative ways to do the things their governments can’t or won’t.

However, we should not be too afraid of the world’s dirty networks, and we can be optimistic about their collapse. One obvious reason I’ve already noted is that the world’s dictators—who are important nodes in dirty networks—are an aging bunch. But big data, social media, and the internet of things provide deeper structural reasons to be hopeful. In the next chapter I offer five reasons—phrased as propositions—that I believe are safe propositions for how the internet of things will transform our political lives.

The second is that the internet of things could help people take these dirty networks on, especially if it is configured in smart ways with the wisdom of what we’ve learned over the past twenty-five years. Fortunately, citizens and lawmakers around the world are already using device networks, in the form of social media and big data, to take down many dirty networks. Every year brings more and more examples of how illicit taxation, drug and people smuggling, and corruption get cleaned up. And the two key forces behind this success are social media and big data.

When people see that their governments are weak, absent, or lousy, they make their own arrangements. Unfortunately, there are many parts of the world where the networks of criminals and corrupt officials are much stronger than the institutions of governance. Increasingly it appears that the best way to battle these dirty networks is with civic networks. The civic networks that equip themselves in smart ways with social media are the ones that perform the best.

People have simply started doing more for themselves, especially through social media and over mobile phones. They have started making their own news. They have started talking about corruption and pollution. They have started coordinating their own health and welfare campaigns. Governments were the primary mechanism for coordinating the public good. People like Eman Abdelrahman, Patrick Meier, and Primož Kovačič demonstrated that device networks could help people build surprisingly agile, effective, and resilient governance mechanisms. Abdel-rahman and her friends built their own network of dissatisfied young citizens in Egypt. Meier built his own network of international volunteers for reconstruction in Haiti. Kovačič built his own network of people within Kibera, to serve Kibera.

Wherever and whenever governments are in crisis, in transition, or in absentia, people are using digital media to try to improve their conditions, to build new organizations, and to craft new institutional arrangements. Technology is enabling new kinds of governance. With social media, big data, and the internet of things, people are generating small acts of self-governance in a wide range of domains and in surprising places.

Almost every country in the world now has a digitally enabled election monitoring initiative of some kind. Such initiatives are rarely able to cover an entire country in a systematic way, and they often need the backing of funding and skills from neutral outsiders like the National Democratic Institute.32 But even the most humble projects to map voting irregularities, film the voting process, or crowd-source polling results help expose and document electoral fraud. Such projects allow citizens to surveil government behavior at a local level, though democracy at the national level isn’t necessarily an outcome. Still, the highlight reels of voter fraud can end up online, wearing down bad government.33

Ushahidi is a user-friendly, open-source platform for mapping and crowd-sourcing information. These days, there are well over thirty-five thousand Ushahidi maps in thirty languages.34 In complex humanitarian disasters, most governments and United Nations agencies now know they need to take public crisis mapping seriously. Ushahidi isn’t the only platform, though it is one of the most popular because of its crowd-sourced content and community of volunteers. Ushahidi has claimed many important victories in the battle to provide open records about the supply and demand of social services. In doing so, it has taught the United Nations about managing disaster relief with device networks, and has schooled the Russians about coordinating municipalities to deal with forest fires and lost children.35

Technology exists in places we don’t usually look. Is it providing governance? Device networks haven’t entirely replaced government agencies, but people do use information technology to quickly repair broken institutions. Almost by definition, government means infrastructural control. Maps have historically constituted the index to how infrastructure is organized, and are therefore a key artifact of political power. FrontlineSMS, another cell phone enabled self-governance mechanism, helps to improve dental health in Gambia, organize community cleanups in Indonesia, and disseminate recommendations about reproductive health in Nicaragua.

Just because a development project uses device networks in some way doesn’t guarantee good governance. When states fail to deliver governance goods, communities increasingly step up, digitally. What we’re talking about here is more than service delivery: it is the capacity of communities to set rules, stick to them, and sanction the people who break them. A sovereign state is one that can implement and enforce such policies. When states don’t have these capacities, a growing number of communities use digital media to provide services and do so in ways that amount to the implementation and enforcement of new policies. In other words, citizens with device networks are building new governance institutions.

The real innovations in technology-enabled governance goods are in the domains of finance and health. In much of sub-Saharan Africa, banking institutions have failed to provide financial security or the benefits of organized banking to the poor. This stems from a lack of interest in serving the poor as a customer base, but also from a regulatory failure on the part of governments. In some settings, device networks have bolstered social cohesion to such a degree that when regular government structures break down, strong social ties can substitute. If the state is strong but the society weak, information technologies can do a lot to facilitate new forms of governance.36

Today, wherever financial institutions have failed whole communities, mobile phones support complex networks of private lending and community-banking initiatives. M-Pesa is a money-transfer system that relies on mobile phones, not on traditional banks or the government.37 Airtime provides an alternative currency to government-backed paper. Since several countries in Africa lack a banking sector with regulatory oversight, people have taken to using their phones to collect and transfer value. In the first half of 2012, M-Pesa moved some $8.6 billion, far from chump change.38

Moreover, people make personal sacrifices to gain access to the technology needed to participate in this new institutional arrangement. iHUB research found that people would forgo meat if it would save enough funds to allow them to make a call or to send a text message that might eventually result in some economic return.39 A typical day laborer in Kenya might earn a dollar a day, but the value of personal sacrifice for cell phone access amounts to eighty-four cents a week.40 Two-thirds of Kenyans now send money over the phone. The service is popular precisely because financial institutions are corrupt or uninterested in serving the poor.

Of course, this type of tech-based governance isn’t always positive. In India, prostitutes who used mobile phones to organize and protect themselves also talked about the pricing of their services. Over several years, the prostitutes consistently said that their income gets a big boost when they have access to mobile phones.41 The application of digital media in their business has actually made prostitution a more lucrative career. In many parts of the Philippines, the government is unable to dispense justice in a consistent way, and can’t always follow through in punishing those convicted of serious crimes. So vigilante groups equipped with mobile phones and social-networking applications have organized themselves with their own internal governance structure to dispense justice. Over SMS they deliberate about targets, determine punishments and delegate tasks. Many countries have self-organizing vigilante groups like these that deliberate and unilaterally decide justice when they see the courts fail. Such groups are responsible for more than a thousand murders in the Philippines.42

These extrajudicial groups have exerted such an important global force that the United Nations appointed a special rapporteur to investigate the problem. The investigator reported on these networks across a dozen countries. In the Philippines alone, his reports covered the killing of leftist activists, killings by the New People’s Army, killings related to the conflicts in western Mindanao, killings related to agrarian reform disputes, killings of journalists, and revenge killings in Davao.43 One of the key findings of such studies is that mobile phones have made it much easier for vigilantes to meet, deliberate, and act.

Plenty of these technology-enabled governance systems are stillborn without some kind of state backing. Most of the Congo is unpoliced, and the government cannot track the movement of local militias. In the absence of institutions, the Voix de Kivus network documents sexual assaults, reports on the kidnapping of child soldiers, and monitors local conflicts.44 The United Nations Organization for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, local NGOs, philanthropists, and the U.S. Agency for International Development study the reports. In this case, the organizers admit that there is little evidence of a governance system taking root. Reports of conflict are now credibly sourced and appear in real time, but nobody acts on the knowledge. In order to have serious impact, most social-media projects need to work in concert with governments.

While some people use social media to provide governance goods, a few use social media to damage or destroy governance goods. Bots can be particularly useful to those who oppose social movements or want to prevent public alert systems from building trust. Bots can also be used to make some public figures appear to be very popular, or to discourage new institutions from growing. Indeed coming under attack is the unfortunate consequence of building successful trust networks that are civic, rather than managed by government or the private sector.45 Still, citizens and civic groups are beginning to use bots, drones, and embedded sensors for their own proactive projects. Such projects, for example, use device networks to bear witness, publicize events, produce policy-relevant research, and attract new members.46

These may seem like isolated examples, but the reason such initiatives are important is that they are contagious. In the past ten years, we’ve gone from imagining that the internet might one day change the nature of governance to finding a plethora of examples of how this is done. Cell phone companies across Africa, Latin America, and Asia now offer asset-transfer systems, many of which are structured like M-Pesa. International aid can help to prop up a failing state and fund rebuilding operations in a state that has failed.

Of course, people do the hard work of rebuilding. In the new world order, as people see their state falling apart, they pull out their mobile phones and make their own arrangements. Aging dictators may hold together dirty networks, but in many countries there are inspiring blooms of digital activism. Collaborative spirits and problem-solving technologies have been around for a while, but device networks have made creative forms of implementation possible and durable. People are bringing stability to the most chaotic of situations and to the most anarchic places on their own initiative, and with their own devices.