Beer can be enjoyed without any understanding of its inner workings or methods of production. Sometimes it’s great to mindlessly kick back and just enjoy a beer without analyzing it to death. On the other hand, a well-brewed beer is a deliciously layered and complex product, displaying a vast range of styles, strengths, colors, intensities, textures, and other qualities. It helps to have a little insight into its history, components, manufacture, and sensory qualities to fully appreciate its depths.

Every beer tells a story about its agricultural roots, chemistry, brewing process, measured parameters, sensory qualities, historical context, and more. It’s helpful to have a grasp of how all these qualities relate to the liquid in the glass. Untangling beer’s complexity can be daunting, but if you break it down into manageable pieces, the whole picture will start to come together. Just remember to keep a glass of something foamy and delicious handy as you learn, to remind you of the rewards for all this hard work.

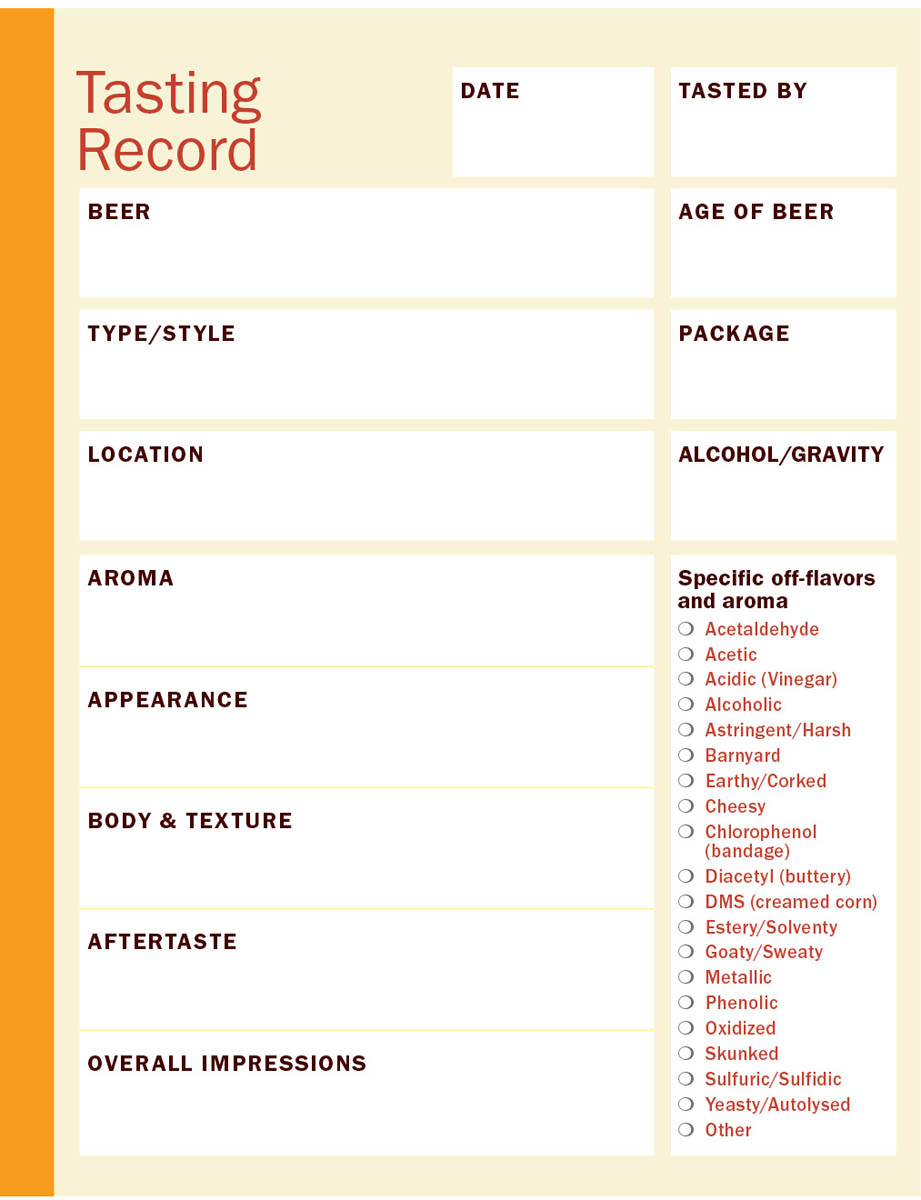

Flavor should be the starting point of any enthusiast’s beer knowledge. No matter what the context, it always comes down to just you and that beer coming to terms with each other. You can read a lot of history, study the style guidelines, absorb other people’s reviews and opinions, and more, but without a firm grasp of the flavors that beer presents to the senses, it won’t mean much. Your journey starts here.

Take a whiff of that ale. Fruity, you say? That’s a good start, but can you break it down a little more? In the tasting world, we strive to be as specific as possible. What kind of fruit? Berries? White fruit, like pears? Dried or fresh fruit? Maybe something tropical? That’s good, but can you go deeper? Pineapple, passion fruit, bananas? If it’s the last, you might go one more step and name the molecule, in this case an ester called isoamyl acetate, which is common in fermentation and is a defining characteristic of Bavarian wheat beers or hefeweizens.

Every one of the aromas and flavors we can detect in beer has its origins in the biochemical processes within the raw ingredients plus the processes that create and modify them during brewing and fermentation. With 1,300 flavor chemicals known to exist in beer, it is impossible to be on first-name terms with more than a small percentage. But with some practice, anyone can develop a familiarity with beer’s many tastes, textures, and aromas. Becoming a serious taster can take a lifetime of study, and while there is no final destination, you can make measurable progress on your journey. I can tell you that it takes a lot of work to get to where you really want to be but that the long and winding road is a joy to ride.

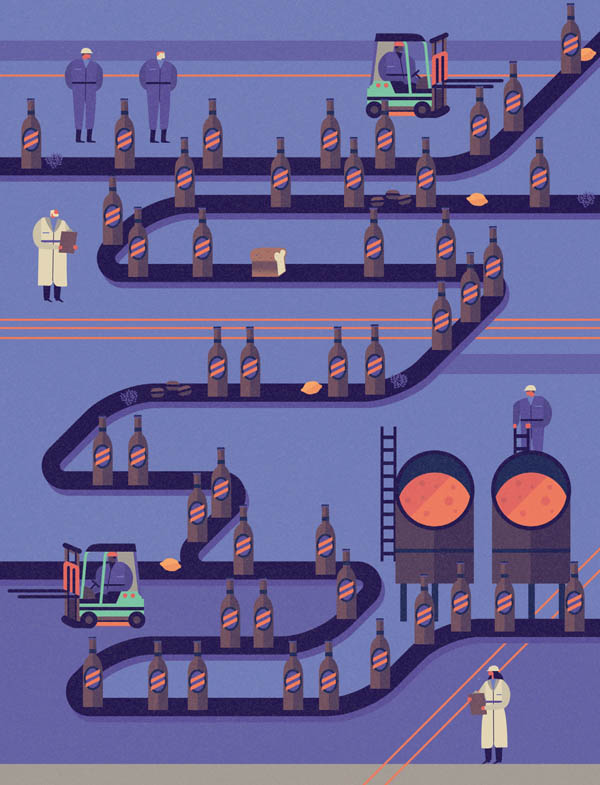

Malt is a product that is created by the controlled sprouting of barley or other grains. As the seed sprouts, it unleashes a host of changes in structure, composition, and flavor. As the nascent plant readies its energy reserves for the formidable task of building itself anew, it activates enzymes, breaks down storage structures, and prepares to transform from a dormant seed into a vital, growing plant. These changes allow us to bend the barley to our will, hijacking its enzymes and gaining access to its starches. During the brewing process, these starches break down into simple sugars to make wort with which to feed the yeast. The yeast will turn the mix into beer, creating alcohol and much more in the process.

The malting process lasts for about a week. While the changes it creates are central to the brewing process, the early stages of malting don’t create a lot of flavor. It is only during the final step, the kilning, that the malt flavor really comes into bloom. Just as a loaf of unbaked bread is pretty lifeless and unappetizing until it is baked to a beautifully aromatic brown, malt needs the heat of a kiln to create the rich, warm, complex flavors we love in beer.

Kilning creates a dual bounty of complex aroma chemicals and those that lend a wide range of color to malt. When heat is applied to sugar or starch mixed with nitrogenous material such as the proteins found in malt, a type of browning called the Maillard reaction occurs. It is the most important chemical process in the browning of any food, from sautéed onions or grilled meat to baked cookies or milk caramel. Most flavors and browned colors in cooked food come from the complex chemical reactions of the Maillard process.

There are dozens of different malt types available to brewers, and each has its own unique set of flavors.

There is another type of browning that does not involve nitrogen, known simply as caramelization. Flavors involved here tend toward burnt sugar or toasted marshmallow. They are most common in caramel malts that are kilned after they develop a lot of simple sugars, and they provide unique raisiny and burnt sugar flavors. Browning also occurs in the brewing process, especially in the boiling kettle; special brewing processes such as decoction enhance this activity.

The chemistry of kilning is terrifyingly complex. Even with the same starting materials, every set of conditions, including time, temperature, pH, and moisture level, creates a different mix of flavors. By manipulating the kilning process as well as the material that goes into it, a maltster can transform a single type of barley into dozens of distinctly different malts that a brewer can use as a start for formulating a recipe.

A sampling of some of the malts available to brewers

The malt flavor vocabulary terms we use to describe beer reflect the universality of Maillard browning in cooking: bread, cracker, biscuit, caramel, toffee, raisins, nuts, toast, roast, coffee, chocolate, espresso. With these terms we have a pretty good match between the words we use and what we can actually experience from malt in the finished beer. If you’re new to this flavor vocabulary and want to know more, I highly recommend going to a homebrew shop and purchasing several different types of malt, such as pilsner, pale ale, Munich, biscuit, caramel (in two different colors, maybe 40 and 80), and perhaps a roasted malt. You can simply pop them into your mouth and taste them, or crush them lightly and make a tea with a little hot water.

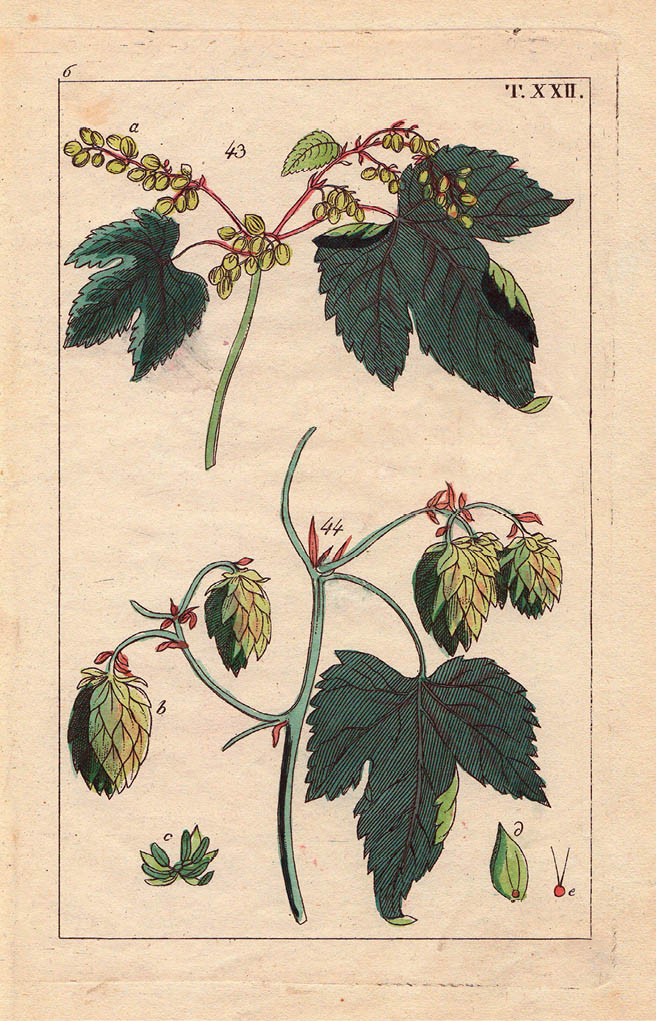

Hops are the papery, cone-like fruits of a climbing vine. They have been continuously used in beer for more than a thousand years, replacing the bitter herbs that preceded them and helped along by the fact that hops have some preservative value that the older bittering herbs, such as bog myrtle, lack. Unlike those of barley malt, hop aromas are created mostly by the plant itself. Once harvested, the changes in hops are mostly negative — simple deterioration during processing and storage. Bitterness develops as a result of a chemical change called isomerization, which occurs when the hops are boiled during brewing. Hops provide a pleasing bitterness as a counterpoint to malt’s richness, along with aromas ranging from floral to citrus to herbal.

Many biochemical processes can occur across differing plant species, so the flavors in hops that strike us as piney or citrus or herbal are provided by some of the same aromatic chemicals that are found in evergreens, citrus fruit, and herbs. There are more than 200 different aromatic chemicals known in hops, and we don’t have the words needed to describe them all. And of course they’re interacting with each other in a beer, making it even more difficult to untangle the many similar aromas. The best thing we can do is try to note what impression jumps out when we get our first whiff of them in the beer.

Positive attributes include citrus (lemon, lime, grapefruit, orange), grassy, piney, floral (lavender, geranium, marigold), herbal (mint, oregano, rosemary, thyme), and spicy, a term we use to describe the Saaz and related hop varieties, although their aromas really have very little to do with spice. Hops may present some negative flavors as well, like catty (like cat pee) and onion/garlic (like onion powder, not fresh), and if hops are exposed to heat and oxygen during storage, a stinky cheese aroma can develop.

Just as with malt, it may be helpful to purchase some different hops and smell them or make up some simple teas to sniff. The availability of hop varieties changes, so just tell your homebrew shop what you want to do with them, and they’ll help you make a selection..

The bitterness hops provide is of supreme importance in beer, and this aspect of their flavor could not be simpler to describe: bitter. While aromas and flavors may be vastly different between hop varieties, the bitterness they provide is all exactly the same.

The single-celled fungus we call brewer’s yeast metabolizes sugar, producing ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide. If it really were this simple, beer would be a lifeless and fairly bland product. Fortunately, as it ferments our beer for us, yeast churns out hundreds of flavor chemicals. Yeast is quite a complex little creature, employing a huge array of biochemical processes in its business of staying alive and reproducing, but it’s a bit sloppy about cleaning up after itself. Depending on temperature, genetics, and a number of other conditions, yeast releases many volatile chemicals into the beer, affecting the overall flavor and aroma of the finished product. Beyond the characteristics of the yeast strain itself, the most important of these variables is temperature. The warmer the fermentation, the more of these ancillary flavor chemicals that are released, and that means a more complex aroma.

Yeast flavor is strongly driven by genetics. There are hundreds of strains within the main species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and there are a few additional species that also are used in beer. Lager yeast is S. pastorianus; the familiar banana plus bubble gum plus clove of Bavarian hefeweizen comes from a S. cerevisiae strain sometimes called Torulaspora delbrueckii. Various wild yeasts, especially in the Brettanomyces genus, may be present in a few types of Belgian-style specialty beers, which may employ some bacteria as well.

Malted barley and yeast

The broad division between ales and lagers is mainly about temperature. Lager yeast is different mainly in its tolerance of low temperatures, which keep the flavors simple and pure. Because lager strains tend to do their work near the bottom of the tanks, they are called bottom-fermenting. Ale yeasts are top-fermenting, because of their preferred habitat.

Ale or lager — can you tell by looking? Both come in all colors.

While the total experience that is a sip of beer cannot be completely broken down into numbers, there are a few important parameters that brewers regularly measure for quality control, stylistic, or other purposes. These numbers are also used in product literature, competition guidelines, and other contexts. Every beer enthusiast should understand what they mean.

First is original gravity, sometimes also referred to as extract. Before being fermented by yeast and becoming beer, the sugar-rich liquid created by the brewing process is called wort. Its density, or solids content, helps determine the final alcohol content after fermentation. This density is easily measured by a simple instrument called a hydrometer, or by more sophisticated laboratory tools in large-scale breweries.

There are two main systems for expressing original gravity. One uses sugar content as a percentage of total weight. This is a scale called degrees Plato, which is more or less the same as the Brix scale used in winemaking. So, for example, 10 percent solids equals 10 degrees Plato — often shortened to simply °P. Most large breweries use this scale, which originated in the lager-brewing heartland of Europe. You may still see references to the Balling scale, an earlier and slightly less accurate scale, which was replaced some time ago by the Plato scale.

The other gravity scale is British, and it expresses the density of the liquid relative to the weight of pure water. This produces a different-looking number with four digits, a decimal point, and the letters OG (meaning original gravity) before or after: for example, 1.040 OG. It means that a 1.040 wort will be 1.04 times as dense as pure water, weighing 1.04 grams per cubic centimeter. Still common in British breweries, this is the scale most often used by American homebrewers, since British homebrew literature was omnipresent when the hobby was really getting rolling in the 1980s.

The two scales can be converted back and forth. A reliable rule that works at the lower end of the scale is that the last two OG numbers (for example, in 1.040 gravity, use the 40) divided by 4 roughly equals °P (in this case, 10 °P).

Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, in beer is generally measured worldwide in percent by volume, sometimes listed as % ABV or % alc/vol. This is the current U.S. federal standard, and it is used in most other countries as well. Confusingly, percentage by weight is sometimes used, especially according to U.S. state laws. Its use is the result of a post-Prohibition decision by brewers to find a scale to express alcohol content in the smallest-looking number. So, alcohol in a 4% ABV beer is only 3.2% by weight. When U.S. and Canadian brewers were using different units of measure, this discrepancy gave rise to the myth that Canadian beer was stronger.

Gravity and alcohol content are related, but only indirectly, as not all of the solids dissolved in wort will ferment. The brewer has a fair degree of control over this, manipulating the brewing process to affect the sweetness or dryness of the finished beer. Attenuation is the term used to express how much of the wort solids actually ferment. The precise method is to distill and carefully weigh the alcohol and then perform a calculation yielding a number called real attenuation. However, it is far simpler to divide the ending gravity by the starting gravity, resulting in a percentage figure known as apparent attenuation. Because it’s so much easier to calculate, apparent attenuation is used by smaller breweries. The reason the two are not the same is that the alcohol in the finished beer, being less dense than water, distorts the reading, so it is possible to have an apparent attenuation of over 100 percent.

The hydrometer measures the original gravity of beer. The scale is read at the level of the liquid surface.

From a tasting perspective, attenuation affects the sweetness or dryness of the beer. Poorly attenuated styles such as Scottish ales or doppelbocks have a lot of residual unfermented sugar. Pilsners, saisons, and strong Belgian ales are usually fairly well attenuated, with a drier palate. Light, dry, and ice beers are super-attenuated beers for which their brewers have to use industrial enzymes derived from fungi to break down all the malt carbohydrates into fermentable sugars.

High attenuation = crisp, dry beer

Low attenuation = rich, sweet beer

Becoming a better taster is a never-ending journey through both the senses and learning about the many complex processes that go into the manufacture of beer. Reading is a good start, but critical tasting requires an entirely different kind of learning. Books can give you a good framework on which to hang your experiences, but it’s the physical act of getting your nose into the glass and the beer onto your palate that turns a drinker into a taster.

While it is possible to proceed on your own, it’s very helpful — and a whole lot more fun — to do this in the company of like-minded travelers. Judging beer is the ultimate training for a serious taster. Putting a study group together to prepare for a certification exam such as the Cicerone — the beer world’s equivalent to the sommelier exam — or the BJCP (Beer Judge Certification Program) — for homebrewing contest judges — is immensely helpful and highly convivial. We all perceive things differently, so having a small group tasting the same beer and offering different points of view yields many useful insights. To stay sharp, tasting requires frequent practice, and the structured format of competition judging focuses the mind in ways that no casual sipping ever will. I never walk away from a judging table without feeling that I’ve learned something utterly new and unexpected.

A sample score sheet for judging beer

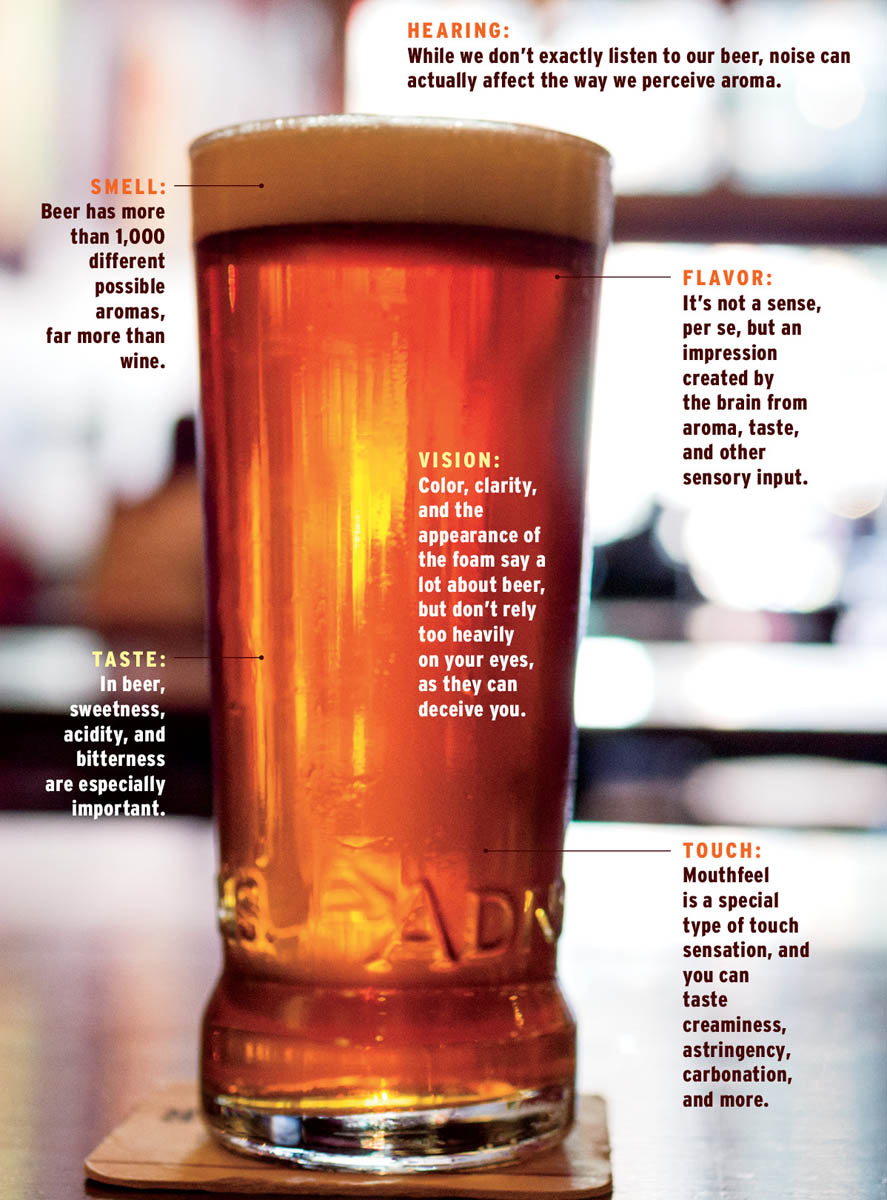

It is obvious that we confront beer with our senses, but it’s important to acquire a working knowledge of how our senses operate as they interact with beer. Each sense responds to stimuli via particular biochemical mechanisms, sending that information to the brain through pathways and processes that are only now beginning to be understood. The brain is stupendously complex. It thinks, feels, acts, recalls, judges, calculates, predicts, responds, and synthesizes, all simultaneously. All these processes and more are active when we taste beer.

It helps to break down the beer-tasting experience into individual senses, while recognizing that there is plenty of interaction among the senses. The light reflected by beer strikes our eyes while it interacts with our chemical senses, but these impulses are just the very first steps on a long path of perception traveling through different parts of our brain before becoming conscious thoughts. How we process, organize, and interpret those sensations is conditioned not only by hundreds of millions of years of evolution, but also by our own life histories, right up to the moment we take a sip. We’ll break that all down into a little more detail to get you started on your tasting journey.

Taste refers to the processes that occur mainly on the tongue but that are also active elsewhere in your mouth to a lesser extent. Everyone knows that sweet, salty, sour, and bitter are primary tastes detected by sensory cells called taste buds. However, science has uncovered more: umami, a savory taste that is a marker for protein; fat; carbonation; metallic ions like iron and copper; and kokumi, a still disputed quality similar to umami. It is likely that there will be more discoveries before we have a complete list.

Contrary to popular conception, the different tastes are fairly evenly distributed on the front half of the tongue, not in concentrated areas for each taste like the old tongue taste map showed. There are areas on the sides of the tongue toward the back that are more sensitive to sourness, and another area at the very back edge of the tongue that is a bit more sensitive to bitterness, umami, and perhaps sweetness as well.

Like all our senses, taste has evolved to help us understand our environment and keep us properly fed and safe. It is so critical to our survival that there are three pathways to the brain, so that if one should become damaged, we still have backups. Once leaving the tongue, one of the first places the taste signals reach is the brain stem, the most primitive part of our brain, which controls heartbeat and respiration, among other things. It is the brain stem that makes the judgment as to whether a taste is pleasant or not.

Each different taste has a specific mechanism for triggering a nerve impulse, and these may range from lightning-quick in the case of salt and sour to somewhat slower for tastes such as bitterness and umami. This is important, because it forces us to think of the tasting act as having a time dimension. We’ll come back to that.

In addition to taste, your mouth has a system of sensory nerves that can detect textures and chemical stimuli. Because beer has a lot of textural qualities, this is an important quality, giving us information about mouthfeel, carbonation, body, heat, cold, chile heat, menthol, and astringency. These nerves are fed by a branching structure called the trigeminal nerve, so these mouth sensations are usually called trigeminal sensations.

The perception of aroma is a good deal more complex, both in the number of smells — or as scientists say, odorants — that can be perceived as well as in the way the sense connects to the brain. Humans have the ability to detect about 10,000 different aromas. Recent estimates are that about 1,300 can be detected in beer.

We possess two slightly different senses of smell. One, the orthonasal, is right where we expect it, at the top of the nasal cavity. Responding to molecules coming in through the nostrils, it is a bit more analytical and helps identify the smells we encounter. A second type, called retronasal, is a little further back in the head and responds more strongly to aromas coming up through the back of the throat; it is wired to the brain differently to be more involved in familiarity and preference. Retronasal impressions also tend to be perceived more as flavors than as aromas. Flavor itself is an imprecisely defined perception that is a bit more complex and multidimensional than either taste or aroma alone. The brain produces flavors from a mix of taste, aroma, and perhaps even mouthfeel sensations.

These two olfactory centers connect to some very ancient and primitive parts of our brains, deep inside our heads and far from the cerebral cortex, where actual thinking and language occur. These primitive parts of the brain are involved in emotion, memory, and other noncognitive processes. As a consequence, we perceive aromas not as objective observers, but as subjective individuals, with perceptions filtered through emotions and memories created by our life experiences.

Everyone struggles with tasting vocabulary. Our brain is very good at creating and recalling emotions based on aromas, but as that sense is only indirectly connected to higher cognitive centers, the brain does a terrible job of turning aroma into vocabulary. It’s just not built that way. There are tricks to make the most of our emotional memory when we’re tasting. Since aroma often triggers very specific memories, you can sometimes linger and tease out what the aroma memory is all about and the place it takes you to. If you linger in those memories, they often help you identify a specific aroma — candy, perfume, cookies, smoke — that can be matched to the beer in front of you.

In addition to taste and aroma, trigeminal sensations give us information about textures such as mouthfeel, body, carbonation, and astringency. These can help determine whether a beer is correct to its style or even pleasurable. A beer’s body is largely determined by its protein structure, a loose network forming what scientists call a colloidal state, which in beer is really just a more dilute version of what happens in gelatin, trapping water and creating a viscous texture. In addition, some gummy carbohydrates called glucans and other similar substances add the same slippery/creamy quality to beer as what’s found in a bowl of oatmeal, where they’re also present. Rye, unmalted barley, and certain other grains besides oats can add the same texture. Astringency is always a negative in beer, a result of tannins (polyphenols) that may have leached from barley or hops and perhaps were exacerbated by the brewing processes.

Vision creates expectations, which can be a good or bad thing depending on the context. We are so dependent on vision that we easily fool ourselves, even ignoring contradictory evidence from other senses to fit what we see. A beautiful beer with a gorgeous head, shimmering in a great glass, will flat-out taste better simply because we expect it to. Embellishments like brand names create the same sort of reality-twisting expectations, which is why beer is delivered in beautiful and entertaining packaging and competitions are normally conducted blind.

Seasoned tasters have a method that takes advantage of their senses and the behavior of the beer itself to extract the maximum information from every sip.

Start with a quiet and well-lit location, free of distracting aromas. Beer is best appreciated in glassware that has a bit of an incurved rim, as this holds and concentrates aroma. It is also advisable to fill the tasting glass less than half full in order to have a place for those aromas to collect. Finally, try to serve beer at an appropriate temperature, perhaps from 38° to 42°F (3° to 6°C) for lagers and a few degrees warmer for ales. No beer worthy of serious tasting is meant to be served ice-cold.

Aroma always comes first. Different aromatics come out of the beer over time, so some may be perceptible only for a minute or so, then will waft away forever. Take small sniffs rather than deep inhalations. Think about what pops into your mind and try not to censor yourself. If the smell triggers a memory, try to tease out what your tasting brain is trying to tell you. Also, make some kind of qualitative judgment. Is it pleasant? Appropriate? Harmonious? Is there anything out of place or even unpleasant?

Then, take a sip. What’s your first impression? It’s likely to be a bit of sweetness, perhaps some acidity if that’s present, and the prickle of carbonation. Don’t be too quick to swallow. Let the beer warm up a little on the floor of your mouth. As it warms, more aroma and flavor will be released. After a few seconds, note what’s happening. Bitterness will start to build as sweetness declines, shifting the balance. As you slowly swallow, close your lips and exhale gently through your nose. This should produce that retronasal sensation. Again, note any thoughts or impressions. At the end of the taste, do you notice anything harsh or unpleasant, especially astringency? The finish and aftertaste should always be pleasant and clean. Now that it’s over, think about the entire taste over the past minute or so. Are all the parts good? Does the flavor pay off what the aroma promised? Are the flavors balanced and working together in a pleasing way? Is the beer what it purports to be? Then, finally, the important question: Do you like this beer?

Beer as we know it evolved in different parts of Europe following four main traditions: British ales, Belgian ales, German top-fermenting ales (including wheat beers), and Bavarian (German/Austrian) lagers. While the history is quite complex, these four interconnected traditions are the starting point for any study of beer from a stylistic perspective. Lagers were brought to the New World by German and Austrian immigrants, and the style evolved into its own unique tradition, forming the basis for most of the world’s mass-market beers. These four traditions have also been the basis for enthusiastic reinvention by an American craft beer movement that has now gone global, so things are evolving rapidly. Here’s a brief description of these four great style traditions, each forged by a mix of available raw materials, climatic conditions, tax laws, water chemistry, gastronomic traditions, whim, necessity, geopolitics, and much more.

Beer in the British Isles was well established long before the Romans arrived in 54 BCE. In the medieval period, as in the rest of Europe, unhopped, top-fermented ales were the norm. Britain was the last region in Europe to convert to hopped beer, over the course of the fifteenth century, most experts say. It was not a homegrown invention but arrived with Flemish immigrants who brought an entire brewing tradition with them, including the word beer.

Gradually, English drinkers developed a taste for bitter beers, and the unhopped ales died out altogether. Strong, hoppy, amber-colored beers called October beers came into fashion, brewed most famously on private estates, and they were always described as being of very high quality. Modern styles started to evolve with industrialization in the early eighteenth century. A dark brown ale called porter and its many variants, including stout, became hugely popular in the rapidly expanding London in the eighteenth century; by 1800, porter dominated the home marketplace and was widely exported as well.

A strong distinction was made between beers brewed for immediate consumption, called running or mild ales, and those destined for a year or more of aging, during which time they developed a desirable vinous — but not sour — character referred to as “stale.” In general, the aged beers were stronger and more highly hopped than the mild ones.

Around the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was a surge in the popularity of the October beers, which started to be referred to as pale ales. Over the next few decades, they became associated with their shipment to India and took on the name India ale or India pale ale. A gradual shift created a separate style apart from the old October beers — paler, drier, and a bit lower in alcohol. As the nineteenth century progressed, there was a good deal of interest in the more drinkable, lower-cost mild beers, and they began to dominate. A dark, light-bodied vestige of porter became known as dark mild, and this would become the main beer in England in the first half of the twentieth century. A lighter, mild form of pale ale, increasingly called bitter, was also popular.

Due to the extreme deprivations during WWI and the existence of prohibitionist groups similar to those in America, British beers dropped a couple of alcohol percentage points around that time, and they have never really bounced back. The die was cast for English beer as we know it by about 1920. Much of it was served in the form of real ale, naturally carbonated in the casks, with the final stages of fermentation and conditioning being handled by the pub’s cellarman. This results in a lightly carbonated, living product that, when done right, offers a sublime drinking experience. Unfortunately, it takes a lot of care and knowledge to get it right, and the beer, once tapped, starts to go flat and sour within a couple of days.

Starting in the late 1960s, the British brewing industry attempted to switch to force-carbonated kegs and even bulk-delivered cellar tanks. There was an uproar among purists, and an organization called the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) was formed in 1971 to protect traditional cask-served real ale. It failed to stop keg beer and lager from dominating the marketplace but did manage to save its beloved real ale, if only as a specialty beer, holding on to something like 15 percent of the UK market.

Scotland’s brewing tradition largely parallels England’s. While the story is often told that the cooler temperatures up north and a dearth of hops led to smooth, dark, and malty beers, there is little evidence to support this. While there is a range of traditional Scottish ales that are a bit darker and maltier than those in England, for the most part you’ll have to hunt them down. English-style bitters, pale ales, and international-style lagers dominate the market. There is a famed strong, sweet beer known particularly as Scotch ale that is a Scottish-brewed interpretation of an earlier English product called Burton ale. Ireland took a liking to porter early on and ever since has defined itself as the nation of stout.

A soulfully roasty stout in an Irish glass

On the continent, an unhopped ale called gruitbier was universal in medieval times. Spiced with secret ingredients, it was heavily taxed, usually to the benefit of some ecclesiastical organization. By 1000, hopped beer started to appear in North Coast cities like Bremen. It steadily advanced, to Hamburg, Amsterdam, and then Flanders by 1300 or so, finally jumping the Channel to England around 1400.

Yarrow, juniper berries, and ground ivy — some of the ingredients used in gruitbier

In addition to malt, both wheat and oats were used in beer, although because of its value in baking, the use of wheat in brewing was frequently restricted. What these early beers tasted like is unknown, but there appears to have been a variety of them, with each town or region producing its own specialties. In those days, most beers were brewed in two strengths: a low-alcohol beer brewed year-round for quick, everyday consumption, and a full-strength winter-brewed version for serious drinking. Stronger specialty beers also existed.

Oats were once widely used for short-lived session beers but can be useful for adding creamy texture to modern beers.

It is believed that in Bavaria, the desire to brew a lighter beer year round led to the development of uniquely cold-tolerant yeast and a style of beer called lager, from the German word meaning “to store,” indicating an extended aging period. The history is a little fuzzy, but this may have happened as early as 1500. At cool temperatures, yeast produces very little flavor, so most lagers emphasize the flavors of the malt and hops, on top of a smooth, clean palate.

Prior to 1840 or so, most of the Bavarian lagers would have been dark, or “red,” beers. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Continental brewers were starting to adopt the more advanced English malt kilning technology, allowing them to produce paler beers. A revolutionary golden-colored beer called pilsner was born in Bohemia in 1842 and was immediately a smash hit. Similar beers appeared in Germany a decade or two later. A pale orange-ish amber beer was developed in Vienna at about the same time; it would soon become associated with Munich’s famous Oktoberfest. Stronger amber-colored beers were known as bocks, and these were traditionally associated with spring.

Bavarian lager became a juggernaut that rolled over many earlier traditions, but some specialized ales persist to this day, most notably in the Rhine cities of Düsseldorf and Köln, with altbier and Kölsch, respectively. Berlin has long been famous for a sour and lactic wheat beer called Berliner Weisse, and a number of related styles existed in nearby towns. Some of these specialized beers, extinct for many decades, are starting to be given new life by dedicated brewers.

Even in lager-drenched Bavaria, top-fermenting beers survived — in the form of wheat ales known as weizens. Originally a perquisite of the royal Bavarian court, the style was privatized in the 1830s and remains popular today. It is most often served with yeast in the bottle, and this style is called hefeweizen.

Belgium, a small nation squeezed between larger militaristic empires, has managed to preserve an idiosyncratic beer tradition that draws admiration from all serious beer enthusiasts. While pilsner may have the lion’s share of today’s beer marketplace, Belgium still retains its galaxy of unique styles, some with very ancient roots. The most historic of all Belgian beers are wheat beers such as the milky, spiced witbier (white beer) style, and its wildly sour cousin lambic, both based on the same brewing process but with radically differing fermentation regimes.

Belgium is notable today for many high-alcohol beers, an emphasis on malty rather than hoppy flavors, the use of sugar to lighten the body, and above all a huge variety of very characterful yeast strains. Belgian brewers consider their beers art in a way that’s different from their European neighbors, and the result is that Belgian beers display wildly differing and highly creative and personal points of view.

Beers with a strong religious theme are common, with some even being brewed by Trappist monasteries, but these are modern in origin. Whatever monastic brewing tradition existed in Belgium prior to 1789 ended when the French Revolution shut down all monastic institutions at that time. None reopened until the 1830s, and very little brewing was done until about 1900. The beers we know today as abbey or Trappist began appearing in the 1920s and 1930s. Counter to our expectations, these Belgian styles are more derived from bocks, Scotch ales, and pilsners than from anything from Belgium’s monastic past.

Since the Belgians see the brewmaster as an artist above all else, a very personal point of view is usually present, and as a result many beers don’t fit within the restrictive guidelines assigned to specific styles. While there are a few well-defined Belgian styles such as abbey dubbels and tripels, witbier, lambic, and saison, a good portion of beers brewed there intentionally shun specific style guidelines as restrictive and unoriginal.

In the United States, Germans and other central Europeans with beer traditions began pouring into the country around 1840. Prior to their arrival, the United States was not much of a beer-drinking country. Agricultural limitations and difficult travel in the vast spaces favored a more portable potable, in the form of spirits such as rum and whiskey.

For the nineteenth-century German immigrants, beer culture was an indispensible part of life, and they began setting up shop, brewing beer and establishing saloons and beer gardens in which to enjoy it. At first they brewed the beers they knew from home: malty Münchners, dark Köstritzers and Kulmbachers. But it became obvious after a while that these calorie-laden beers didn’t fit either the meat-rich diet or the steamier climate of the Americas. American-grown barley, with its high protein content, was also a problem, creating hazy beer with a sharp, grainy taste.

These problems were all solved with the gradual popularization of American adjunct-based pale lagers, brewed with the addition of about 25 percent rice or corn, which lightened the body and diluted the protein. Being crisper and more refreshing, they also suited the climate better. Lawnmower beer was born. Over the next hundred years this type of beer, eventually in the hands of just a few giant conglomerates, would come to dominate not only the United States, but most of the rest of the world as well.

By the 1970s, the number of American breweries had shrunk from about 3,500 in 1875 to well under 100, virtually all producing similar adjunct lagers that even their own customers couldn’t tell apart. Inspired by experiences with beer culture in Europe, young Americans began home-brewing their own offbeat versions of classic pale ales, stouts, porters, and many more. When they started to go commercial, craft brewing was born. By 2013, there were more than 3,000 American breweries, with a huge number more around the corner. Market share by dollars currently approaches 50 percent in craft-hot regions like Seattle and Portland. After decades as a lifeless sea of mass-market adjunct pilsners, the United States has become a real beer paradise. The excitement of this movement has spread to many other countries, and they are catching up fast.

While this is just a brief introduction to help set the stage for your further exploration, it’s important to note that each grand tradition has a wide variety of specific styles and also of beers that live between or outside of standard style guidelines. For more specifics on the way styles are defined for competition purposes, you can access the homebrewing BJCP (Beer Judge Certification Program) style guidelines or the Brewers Association World Beer Cup and Great American Beer Festival guidelines for free online. Just be aware that such guidelines represent a snapshot in time and necessarily draw hard and fast lines when in some cases there really aren’t any, and so they do not necessarily reflect the diversity and historic variability of these style traditions. And, of course, some brewers scoff at style guidelines altogether, so it is always wise to look outside the boundaries.

Amber Ale

Brown Ale

Doppelbock

Gueuze

Kölsch

Maibock

Red Ale

Schwarzbier

Tripel.

Because of their very high carbonation levels, Belgian tripels and other strong ales should be served in glasses with a lot of extra headroom.

The presentation of beer deeply affects our enjoyment of it, so it’s worth a little effort to get this right. A lot of the already discussed information about distractions, serving temperatures, and having the proper expectations applies here as well.

There is a lot of mumbo-jumbo out there regarding beer glasses, and there is a lack of any real science. I do think that for critical tastings, a curved vessel like a wineglass is hard to beat, and of course there are beer-specific glasses that share this feature. It’s also a good idea to pay attention to traditional glasses associated with specific styles, such as the elegant footed flute used for pilsners.

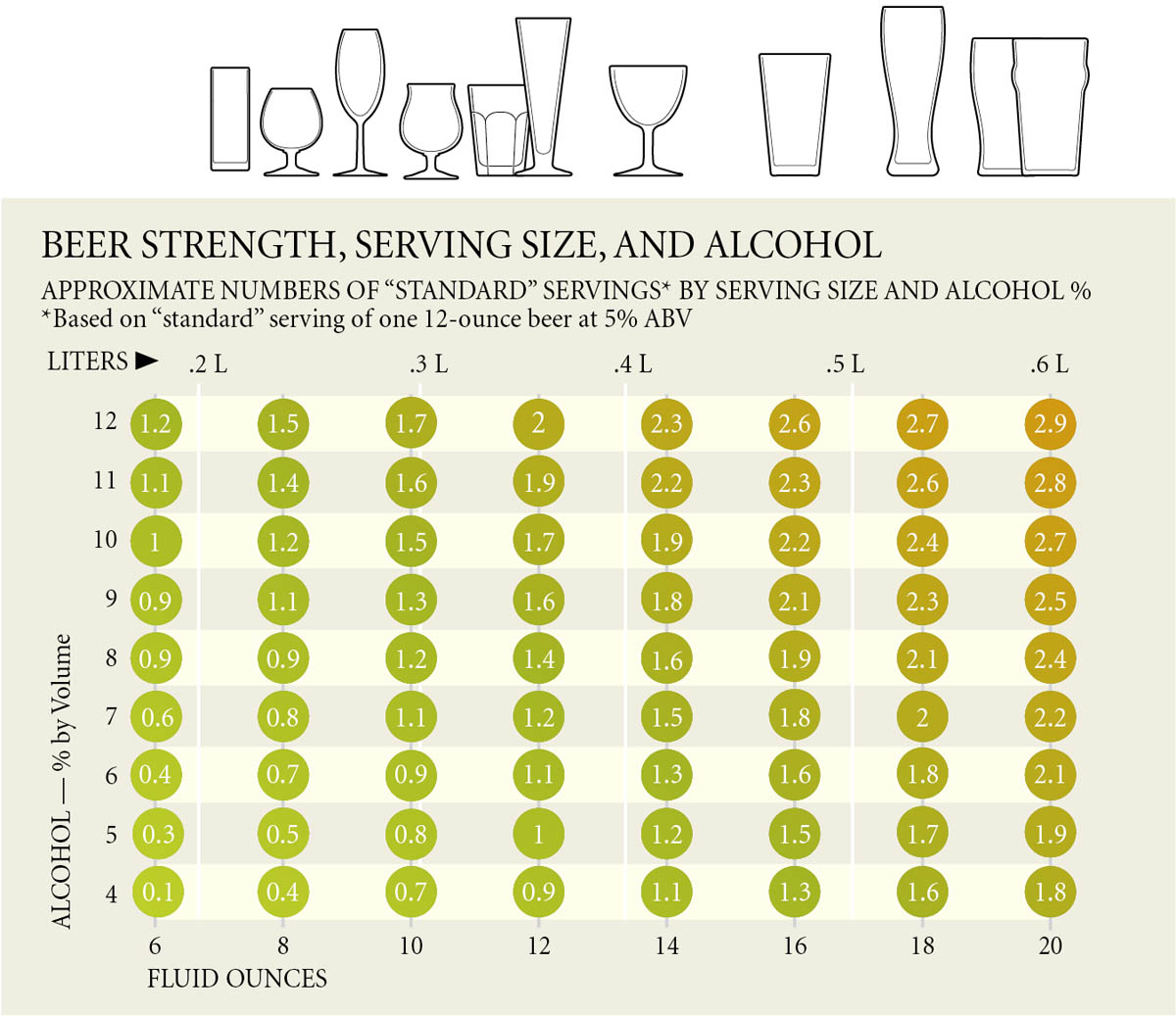

It makes sense to serve beer in portions related to its strength — nobody needs a pint of barleywine. Session beers such as European lagers and English bitters are often served in large glasses of about a half-liter. It’s a simple calculation to figure how much beer of any given alcoholic strength will equal a standard drink serving, usually figured at 14 grams or 17.7 milliliters (0.6 ounces) of pure alcohol.

What constitutes a proper pour varies from place to place and has undoubtedly been the cause of fistfights, as people tend to feel passionate about their beer and how it’s presented. While there may be arguments over a beer’s head, most of us enjoy the appearance and texture as long it doesn’t rob space in the glass that might be better filled with beer. For that reason, glasses for highly carbonated beers such as weissbiers and Belgian ales often have an oversized headspace as an accommodation.

There is a tradeoff between the density of the head and the time it takes to pour it properly. In the impatient United States, beers are normally poured without a lot of fuss, resulting in a perfunctory head that collapses fairly rapidly. In the traditional lager regions of northern Europe, special taps are used that deliver a little more foam. The beers are poured, allowed to settle, and then topped off in two or more steps. This creates a dense, creamy foam with tiny bubbles that lasts a good deal longer than the American type of pour. The proper amount of foam served on a pint of real ale in England is a topic as hot as an electric eel, and I won’t touch it, except to say that as you move north in that country, more head becomes the norm.

If you like a firm-foam type of pour, you can duplicate it with bottled beer. Just pour the beer right down the center, allow it to settle, pour again, and repeat as often as necessary to fill the glass. You’ll be rewarded with a rich, creamy head and, as a bonus, a beer that is relieved of some excess gas, making for a better tasting experience.

One should also be aware that draft systems need precise engineering and frequent cleaning, and that, sad to say, many serving establishments are less than diligent. Also, many tap systems in the United States are incorrectly pressurized with mixes of CO2 and nitrogen rather than pure CO2, resulting in less than adequate CO2 pressure and thus allowing the beers to lose their carbonation within a few days.

Beer is a perishable product. With the exception of very strong beers, few are meant to age after leaving the brewery. Most normal beers change noticeably after a few months. How quickly they deteriorate depends on the beer and the storage conditions. Heat is the number one enemy, so store beer as cool as you can, and avoid repeated temperature swings. Light also deteriorates beer, transforming certain hop substances into a chemical called mercaptan, which has an unpleasant skunky aroma. In full sunlight, it takes just seconds to skunk a beer. Because skunkiness is caused by blue light, brown bottles offer fairly good protection, but green and clear bottles do not. It’s not only bright sunlight that’s a problem. In the wrong bottles, beer will skunk inside the store or cooler case when exposed to fluorescent lights.

Here are some commonly encountered glass shapes that are useful to have handy when tasting your way through a year of beer. Note: Glass sizes are noted with some extra room reserved for foam.

Footed Pilsner Great for all pale, bright beers, not just pilsners. Tapered shape supports the head.

Varies, but generally 10 to 14 ounces (300 to 410 ml).

No-Nick and Curvy Pint Two capacious classics for British beers. No-nick refers to the bulge that keeps the rims from nicking when bumped together.

Imperial pint, 20 ounces (590 ml), also available in half–imperial pint (300 ml) size.

“Willi” Glass A modern lager glass equally useful for light and dark beers. Incurved rim helps trap aroma.

Half-liter (17 ounces); smaller sizes may be available.

Pokal A short-stemmed smaller beer glass with a traditional bucket shape properly used for doppelbocks, or a modern curved profile useful for a wide variety of beers.

Sizes vary, but generally about 1/3 liter (11 ounces).

Snifter A stubby footed form originally meant for spirits such as brandy. Great for strong beers that need to be served in small quantities.

8 to 12 ounces (240 to 350 ml).

Seidel/Stein Chunky handled mugs make holding onto those big beers easier. Classic for Oktoberfest or any kind of biergarten drinking. Lidded versions keep the bugs out. “Krug” is a very similar vessel, usually made of stoneware.

Full liter or “Maß” (33 ounces) or half-liter sizes (17 ounces) available.

Tulip Tall footed glass interpreted in a variety of designs, but the best have a curvaceous shape that flares at the rim. As close to an all-purpose beer glass as I have found.

12 to 16 ounces (350 to 470 ml).

Chalice A Belgian glass with monastic connections, mostly available as brewery-specific imprinted versions. The wide bowl on a tall stem makes a dramatic presentation and reinforces the religious connection.

12 to 14 ounces (350 to 410 ml).

Flute Tall, elegant footed glass similar to champagne flutes or sometimes created specifically for beer. Best used for pale, elegant, strong beers, but glorious for fruit ales.

8 to 12 ounces (240 to 350 ml).

Shaker Pint This squat and unflattering glass was created as half of a cocktail shaker and was never meant for serving any beverage. In the United States, it is the overwhelming choice of bars because of its low cost and indestructibility, qualities that only add to its loathsomeness.

16 ounces (470 ml), but beware, some examples hold only 14 ounces (410 ml).

Weissbier “Vase” This ancient form highlights the luminous beauty of Bavarian hefeweizen and offers plenty of headroom. In Melbourne, Australia, a half–imperial pint version is known as a “pot.”

Half-liter (17 ounces) is the classic, but other sizes are available.

Proprietary Beer Glassware Whether the custom glass is scientifically designed or just a whim of some marketing person, drinking any beer out of its own special glass elevates the beer experience — but note that logoed shaker pints don’t count.

One cannot possibly explore the glories of drinking beer with the seasons and miss out on the opportunity to enjoy it with food. In the old days, people needed little guidance. Beers and their cuisines had evolved to a harmonious state, whether in Germany, Belgium, or elsewhere. Seasonality was built into food just as it was with beer. In a more cosmopolitan world, we are faced with endless choices, so it helps to have a little guidance to improve your odds of putting together a divine combination. The Brazilians use a term — harmonizacão, meaning “harmonization” — that I think is an accurate and elegant way of describing the goal. The idea is to blend the partners in a way that honors both but also transforms them, ideally becoming better than either one alone. A much better term than pairing, I think.

It’s a complex subject, at the moment with little scientific basis or even broad consensus on specifics, but most agree that anyone considering working with beer and food should consider a few points as they ponder the possibilities.

With the huge range in flavor intensities in the beer and food worlds, it’s easy to come up with a combination where one partner totally overwhelms the other. There is no specific method for avoiding this, just simple common sense. Beer’s intensity may be affected by gravity, alcoholic strength, sweetness, bitterness, roastiness, or fermentation. With the food partner, consider not just the main ingredient, but also the cooking method, spicing, sauce, and other items that may be on the plate.

Because beer is made from cooked grain and seasoned herbs, it offers a huge range of possible connections to almost any kind of food. Just look back through the beer vocabulary earlier in this chapter and now think about foods instead of beer. And while it is obvious that flavors that are similar taste good together, that is not the only possible relationship. There are many great partners that have little in common: butter and bread, chocolate and coconut, caramel and nuts. Cast a wide and open-minded net when seeking successful partnerships.

Cheese and beer are among the easiest and most rewarding pairings, a great place to start to explore beer and food.

The dynamics can be a little complex, but fortunately there are a limited number of tongue tastes we need to deal with, so this is more manageable. Tastes like sweet, bitter, and fat are intense in the mouth and need to be countered and brought into balance in the pairing. Alcohol and carbonation also have important roles, especially in relation to fat, which the former dissolves and the latter literally scrubs away. So, sweetness in food can be balanced by bitterness in beer, and that can come from either hops or roasted malts. Umami behaves in much the same way. Fat can be balanced by bitterness and cleansed by alcohol and carbonation. For beers that have noticeable acidity, this acidity can act as it does in a wine pairing and cut through a fatty dish.

On the flip side, beers with big bitter or roasty flavors really need food with a lot of fat, sweetness, or umami to stand up to their intensity.

Counterintuitively, similar tastes can sometimes balance each other out. Sweetness, for example, can only get so sweet, so when you put a sweet beer with a sweet dish, they tend to neutralize each other in a surprising and delicious way. Because beer always brings bitterness and carbonation, the wine rule that the drink always be sweeter than the dessert does not always apply.

Stout with Chocolate Cake

Beer and food harmonizing is not a zero sum game, so it’s nearly always possible to have both of these important relationships working. Tongue tastes are nearly always contrast-y, so the dynamics have to be considered. The aromatic realm offers so many possibly connecting points, it’s a rare dish indeed that can’t find a sympathetic beer complement.

There are some partnerships in which beer can supply a familiar flavor in an entirely new context, re-creating a familiar flavor experience that doesn’t normally include beer — or any drink, for that matter. Here’s an example: Put a gooey washed-rind cheese together with a toasty brown ale, and presto, you have liquid grilled cheese sandwich in your mouth. The dark beer forms the toasty component when there’s no actual bread in the mix. Pair a fruity hefeweizen with a fresh buffalo mozzarella, and you have a milk and fruit explosion that resembles peaches-and-cream ice cream.

Like the toast and cheese example mentioned above, many combinations can work successfully at various levels of intensity, matching more intense beers with more intense foods up the flavor ladder and less intense foods on lower rungs. With the cheese pairing, you start with a beer like a British-style pale ale with just a hint of toasty crispness and put it with a mild and buttery bierkäse or Caerphilly, and you get a buttered-crackers sort of experience. Step it up and you get into various levels of the grilled cheese concept. Move up to an aged cheese like a Parmesan and you go from expanding the cheese flavors to including full-on meaty flavors. With a seriously roasty beer like a Baltic porter or an imperial stout, it transforms into a sort of liquid cheeseburger effect, the beer now supplying the grill marks on the virtual meat. Blue cheese and IPA is another well-known flavor ladder, and almost every harmonization idea works up and down in intensity at least to a certain extent.

IPA with Blue Cheese

Don’t forget to have a look at the way traditional beer-drinking countries put beer and food together. There is a lot to learn from these historic cuisines, and you’ll often come up with some unexpected combinations. Germany, England, France — Alsace, really — and Belgium should be on your list for study.