5

Moderation Kills

A NUMBER OF YEARS AGO, when I was beginning my research project in coronary artery disease, a prominent local physician who disagreed with me announced that he believed in “dietary moderation” for his heart patients. Translation: I don’t care if my heart patients eat some fat. That’s a fairly common sentiment among my medical colleagues. But what are the facts?

In science, a review of many studies on the same subject is referred to as a meta-analysis. Such a review of studies on coronary artery disease was done in 1988, when researchers in Wisconsin analyzed ten clinical trials involving 4,347 patients.

1 Half of the patients had received cardiac rehabilitation, which generally consists of advice to lose weight, exercise, control high blood pressure, control diabetes, stop smoking, and eat less fat. The other half of the patients did not receive such assistance. The results: the “rehabilitated” group had slightly fewer fatal heart attacks than those who did not get the same advice. But the researchers found “no significant difference” between the two groups in the number of nonfatal heart attacks. In fact, the rehabilitated group suffered slightly more nonfatal attacks than those who made no lifestyle changes.

The reason is fairly simple. Those who moderately reduced their consumption of fat did manage to slow the rate of progression of their disease. But they did not completely arrest it, and as it progressed—even at its new, slower rate—it continued to take its toll.

In early 2006, a report published in

The Journal of the American Medical Association resulted in national headlines suggesting that low-fat diets do not decrease health risks. The

JAMA article was based on a study, part of the Women’s Health Initiative of the National Institutes of Health, which followed nearly 49,000 women over eight years, and it found that those prescribed a “low-fat” diet turned out to have the same rates of heart attacks, strokes, and cancers of the breast and colon as those who ate whatever they wanted.

2Almost buried in the news reports about this latest, largest, most expensive study ever was this incredibly important fact: the women who were supposedly consuming a low-fat diet were actually getting 29 percent of their daily calories from fat. For those on the front lines of nutritional research, that is not “low fat” at all. It is three times the level—around 10 percent of daily caloric intake—that researchers like me recommend through plant-based nutrition.

The Women’s Health Initiative study and the conclusions drawn from it bring to mind an analogy. Suppose researchers were studying the following question: does reducing vehicular speed save lives? They find that when a car strikes a stone wall at 90 miles an hour, all its occupants perish. The same result occurs when the car hits the wall at 80 mph—and at 70. Conclusion: reducing speed doesn’t save lives. (Meanwhile, everyone ignores a small study showing that in a crash at 10 miles per hour, everyone survives.)

The Women’s Health Initiative researchers were quoted as saying that their results “do not justify recommending low-fat diets to the public to reduce their heart disease and cancer risk.” True, they certainly do not justify recommending diets containing 29 percent fat, the level currently endorsed in the U.S. Dietary Guidelines. But those of us who have been studying the matter already knew that. The Women’s Health Initiative study simply confirms that the guidelines are wrong: we should be recommending diets far lower in fat than those featured in this research.

Over the years the meta-analyses, such as the one conducted by the Wisconsin researchers, have consistently shown that coronary patients who reduce their fat intake do somewhat better than those who do not. But almost always, the best outcome is a slowing of the rate of progression of disease in patients who receive treatment—not putting an absolute stop to it.

These results are not good enough. We should be aiming much higher: at arresting coronary artery disease altogether, even reversing its course. And the key to doing this, as my research demonstrates, is not simply reducing the amount of fat and cholesterol you ingest, but eliminating cholesterol and any fat beyond the natural, healthy amounts found in plants, from your diet. The key is plant-based nutrition.

Let’s review what we know about the science. Heart disease, as I have already stressed, develops in susceptible persons when blood cholesterol levels rise higher than 150 mg/dL.

3 The converse is also true. A person who maintains blood cholesterol under 150 mg/dL for a lifetime will not develop coronary artery disease—even if he or she smokes, has a family history of coronary disease, suffers from hypertension, and is obese!

One case in point: the Papua Highlanders of New Guinea. These people are traditionally heavy smokers. Even nonsmokers among them breathe in lethal doses of secondhand smoke in communal hutches. Not surprisingly, the Papua Highlanders suffer many lung disorders, thanks to the smoking. But studies of those who live into their sixties and beyond have shown that despite the well-documented risk to heart health that is posed by smoking, they have no coronary artery disease.

4 They are protected by their diet, which consists almost entirely of nineteen separate varieties of sweet potatoes.

Nutrition impinges on cardiovascular health in several critical ways. The most obvious, of course, is that a diet high in fat and cholesterol causes blood lipid levels to rise, thus setting off the process of plaque formation.

But isn’t “dietary moderation” enough to stop that process? If you cut back considerably on fat and cholesterol, shouldn’t you be all right, as my colleague suggested? Surely, just a little bit wouldn’t hurt.

Wrong! That’s what you must remember every time you are confronted with that tempting tidbit topped with melted cheddar and bacon bits. Moderation kills. And to understand why, you have to understand something about metabolism and biochemistry.

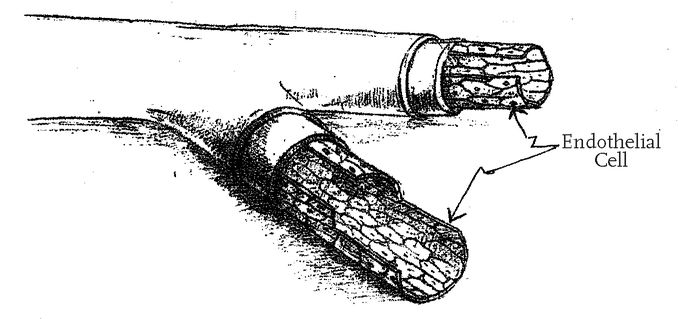

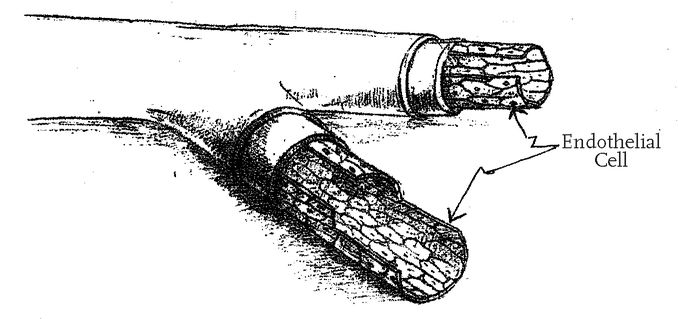

Every segment of our bodies is comprised of cells, and every individual cell is protected by an outer coat. This cell membrane is almost unimaginably delicate—just one hundred-thousandth of a millimeter thick. Yet it is absolutely essential to the integrity and healthy functioning of the cell. And it is extremely vulnerable to injury.

Every mouthful of oils and animal products, including dairy foods, initiates an assault on these membranes and, therefore, on the cells they protect. These foods produce a cascade of free radicals in our bodies—especially harmful chemical substances that induce metabolic injuries from which there is only partial recovery. Year after year, the effects accumulate. And eventually, the cumulative cell injury is great enough to become obvious, to express itself as what physicians define as disease. Plants and grains do not induce the deadly cascade of free radicals. Even better, in fact, they carry an antidote. Unlike oils and animal products, they contain antioxidants, which help to neutralize the free radicals and also, recent research suggests, may provide considerable protection against cancers.

Among the body parts we injure every time we eat a typical American meal is the endothelium itself—the lining of the blood vessels and the heart—and the remarkable role it plays in maintaining healthy blood flow. The endothelial cells make nitric oxide, which is critical to preserving the tone and health of the blood vessels. Nitric oxide is a vasodilator: that is, it causes the vessels to dilate, or enlarge. When there is abundant nitric oxide in the bloodstream, it keeps blood flowing as if the vessels’ surfaces were coated with the most slippery Teflon, eliminating the stickiness of vessels and blood cells that is caused by high lipid levels and that, in turn, leads to plaque formation.

There is mounting evidence of the critical importance of the endothelium. German researchers recently studied more than 500 patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease. They performed angiograms on the patients and also drew blood, quantifying the number of endothelial progenitor cells—the cells that restore and replace endothelium—in the bloodstream of each subject. Over the following twelve months, the researchers found that patients with the fewest endothelial progenitor cells fared most poorly. Those with the most cells did best of all.

5Dr. Robert Vogel, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, has conducted some astonishing studies that demonstrate, among other things, what a toxic effect a single meal can have on the endothelium.

6 Dr. Vogel used ultrasound to measure the diameters of the brachial arteries of a group of students. Then he inflated blood pressure cuffs on the students’ arms, stopping blood flow to their forearms for five minutes. After deflating the cuffs, he used the ultrasound to see how fast the arteries sprang back to their normal condition.

One group of students then ate a fast-food breakfast that contained 900 calories and 50 grams of fat. A second group ate 900-calorie breakfasts containing no fat at all. After they ate, Dr. Vogel again constricted their brachial arteries for five minutes and watched to see the result. It was dramatic. Among those who consumed no fat, there was simply no problem: their arteries bounced back to normal just as they had in the prebreakfast test. But the arteries of those who had eaten the fat-laden fast food took far longer to respond.

Why? The answer lies in the effect of fat on the endothelium’s ability to produce nitric oxide. Dr. Vogel closely monitored endothelial function of subjects and found that two hours after eating a fatty meal there was a significant drop. It took nearly six hours, in fact, for endothelial function to get back to normal.

If a single meal can have such an impact on vascular health, imagine the damage done by three meals a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year—for decades.

But isn’t it enough simply to reduce your cholesterol levels? Why insist upon a radical change in diet, if there are other ways to reach the cholesterol goals?

Recently, the

New England Journal of Medicine reported on a study in which massive doses of cholesterol-lowering drugs were used to reduce total cholesterol well below 150 mg/dL. Three out of four of the heart patients involved seem to do very well under this regimen. But it was not a complete success. Even with their cholesterol levels satisfactorily reduced, one out of every four of the patients in the study sustained a new cardiovascular event or died within two and a half years of starting this treatment.

7I was struck by the fact that there were so many problems even though both total cholesterol and LDL levels in those patients were reduced well into the range I suggest and often below that. So I called the study’s author, and discovered an extremely important variable: there had been no nutritional component to the study. When I asked what study participants had been eating, he replied, “It was a drug trial.” They had continued to eat the same way they ate before the study began. That explains why so many patients failed.

Remember how I ask my patients to compare their disease to a house fire that they’ve been spraying with gasoline—and how I insist that in order to put it out, they must stop spraying it with fuel? That was the problem here. Despite profound cholesterol reduction with medication, the arterial plaque inflammation (the fire) and disease progression were inevitable because the patients were still ingesting the toxic American diet (the gasoline).

The patients in that study who died or whose disease progressed were subsequently tested for highly sensitive C-reactive protein, or HSCRP. This test measures the levels of a specific blood protein that increases with inflammation of the coronary arteries, and it is considered by many cardiologists to be even better than a standard cholesterol measurement at assessing your risk of heart attacks. All those patients who failed turned out to have elevated HSCRP levels.

There is a critical clue here to the overwhelming importance of nutrition. In my experience, fully compliant patients achieve normal levels of HSCRP within three to four weeks of adopting my plant-based nutrition program. The results are prompt, safe, and enduring.

Figure 5. With plant-based nutrition, the endothelial cell is a metabolic dynamo that ensures vascular health.

Twenty years ago, when I started my research, our major focus was on reducing total blood cholesterol levels to below 150 mg/dL and cutting LDL levels to 80 mg/dL or less. But today, it is clear to me that in achieving those goals through plant-based nutrition, we also achieved a corollary result: we restored the body’s own powerful capacity to resist and reverse vascular disease. Plant-based nutrition, it turns out, has a mighty beneficial effect on endothelial cells, those metabolic and biochemical dynamos that produce nitric oxide (see Figure 5). And nitric oxide, as I have noted, is absolutely essential to vascular health—a finding that won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1998.

8- It relaxes blood vessels, selectively boosting blood flow to the organs that need it.

- It prevents white blood cells and platelets from becoming sticky, and thus starting the buildup of vascular plaque.

- It keeps the smooth muscle cells of arteries from growing into plaques.

- It may even help to diminish vascular plaques once they are in place.

To understand how plant-based nutrition facilitates nitric oxide production, you need to have a sense of the biochemistry at play. The essential building block for nitric oxide production is a substance called L-arginine, an amino acid that is in rich supply in a variety of plant foods, especially legumes, beans, soy, and nuts. Figure 6 shows, schematically, how L-arginine fits neatly into the enzymatic action of nitric oxide synthase, which then produces nitric oxide from the arginine and oxygen.

However, as you can also see in Figure 6, there is a competitor for nitric oxide synthase: asymmetric dimethyl arginine, or ADMA, which is manufactured by our bodies in the course of normal protein metabolism. When we have too much ADMA, then L-arginine is edged out for a position in nitric oxide synthase, and the production of nitric oxide fails. There is another delicate enzyme with a formidable name—dimethyl arginine dimethyl amino hydrolase, or DDAH—that destroys ADMA, in order to favor production of nitric oxide. But the usual cardiovascular risk factors (high cholesterol, high triglycerides, high homocysteine, insulin resistance, hypertension, and tobacco use) all impair the ability of that delicate enzyme to destroy ADMA.

Figure 6. The pathway of nitric oxide production—arginine through nitric oxide synthase to nitric oxide—can be blocked by too much ADMA.

This biochemistry explains what is perhaps the key mechanism through which my patients became heart-attack-proof beyond twenty years. Their plant-based diet reduced or entirely eliminated all the above cardiovascular risk factors. The more compliant the patient, the more he or she reduced the risks.

Along the way, they also reduced symptoms such as angina pectoris—chest pain—perhaps the most frightening and incapacitating symptom of heart disease. Normally, physical effort or strong emotion causes the endothelium to go into action, producing nitric oxide, dilating the blood vessels, and thus boosting the flow of blood to the heart muscle. But in a patient with coronary disease, the endothelium’s capacity is badly diminished. His narrowed coronary arteries do not dilate, and therefore his heart muscle does not receive the flow of blood it needs. The result: pain. It may be mild or it may be excruciating. Many patients become “cardiac cripples,” terrified of exerting themselves physically, of making love, of expressing or experiencing strong emotions. To give such patients lasting relief, it is essential to bring more blood to the heart muscle—despite the fact that the blood must flow through partially blocked coronary arteries. How? By restoring the endothelium’s capacity to manufacture nitric oxide.

The effects of a radical shift in nutrition are breathtaking—dramatic and swift. In 1996, I used plant-based nutrition to aggressively reduce the risk factors in a patient with demonstrably poor circulation to a portion of heart muscle. A cardiac pet scan noted the problem just prior to my intervention. Within ten days of her starting a plant-based diet and a low dose of a cholesterol-lowering drug, the patient’s cholesterol level fell from 248 mg/dL to 137. After just three weeks of therapy, a repeat scan showed restored circulation to the area of heart muscle that had been deprived (

see Figure 7). There was no doubt what had happened: a profound change in lifestyle, adopting strictly plant-based nutrition, brought about a rapid restoration of the endothelial cells’ capacity to manufacture nitric oxide, and that, in turn, restored circulation.

That success led to a similar pilot study with Dr. Richard Brunken and Ray Go of the Cleveland Clinic Department of Nuclear Radiology and Dr. Kandice Marchant of the clinic’s Department of Pathology. The results, shown in Figures

8,

9,

10, and

11 (

see here), confirm the ability of plant-based nutrition, in conjunction with cholesterol-reducing medication, to reperfuse—restore blood flow to—the heart muscle previously deprived of adequate circulation. I emphasize that this is not a case of the development of collaterals, naturally occurring bypasses, which take months or years to appear. The heart disease in these patients was long-standing, and the baseline study showed no reperfusion by collaterals; the reperfusion was observed three to twelve weeks after the patients made the lifestyle changes we outlined.

Students of physics will recognize this phenomenon as Poiseuille’s Law, which describes the flow of liquid through hollow tubes. Think of a fire hose replacing a garden hose. Thus a modestly restored dilation of the blood vessels provides a huge increase in blood flow—clearly visible on the scans—and causes angina to disappear within weeks of starting therapy.

The endothelial system for enhancing and protecting our vascular system is brilliant. We can prevent it from breaking down, and we can restore it to good health even after a hazardous lifestyle has injured it. Just in case you are not yet convinced, let’s take a look at what happened to the patients in my original study.